1.4 Nutrition Research and Misinformation

Nutrition Research

If you look online, you will find an overwhelming amount of nutrition information. Social media is full of content telling you what to eat or what not to eat. When you browse the internet or stream your favorite shows you probably see advertisements telling you how to get the perfect body or what to eat to improve your health. Even when shopping for food or groceries you are exposed to marketing tactics trying to convince you that this product is better for your health. Then you get to the checkout counter and you are bombarded with magazines telling you how to eat and showing you what a “perfect body” looks like. The world is full of nutrition information, some of it good, some of it bad, and some of it straight up harmful. Nutrition trends change frequently. In the 1970’s, carbohydrates were vilified but a decade later everyone was fat phobic and trendy diets encouraged replacing fat with sugar. Then, grains, gluten and high-fructose corn syrup were blamed for our bulging waistlines and fat- or protein-loaded diets were praised for their magical weight loss properties. Now, ketogenic diets and juice cleanses are all the rage. No wonder people are frustrated and give up on the whole thing! So what do we believe? Is it really as simple as eliminating one type of food from our diet? Of course not! There is no one size fits all answer. In fact, there are just as many variations of a “healthy” diet as there are people. You have to decide what works best for you and find a sustainable eating pattern that makes you feel energized, keeps you healthy, and helps you maintain a healthy body composition over time. What works for one person may not work for another. There are, however, certain things we can say with a high degree of confidence about the relationships between food and health. For example, we know fiber is important for digestive health and disease prevention, that diets that are excessively high in saturated fats promote heart disease, and that eating fruits and vegetables reduces your risk of chronic diseases. How do we know these things? Because there is a vast amount of research substantiating this information. Valid nutrition information is obtained through years of scientific research.

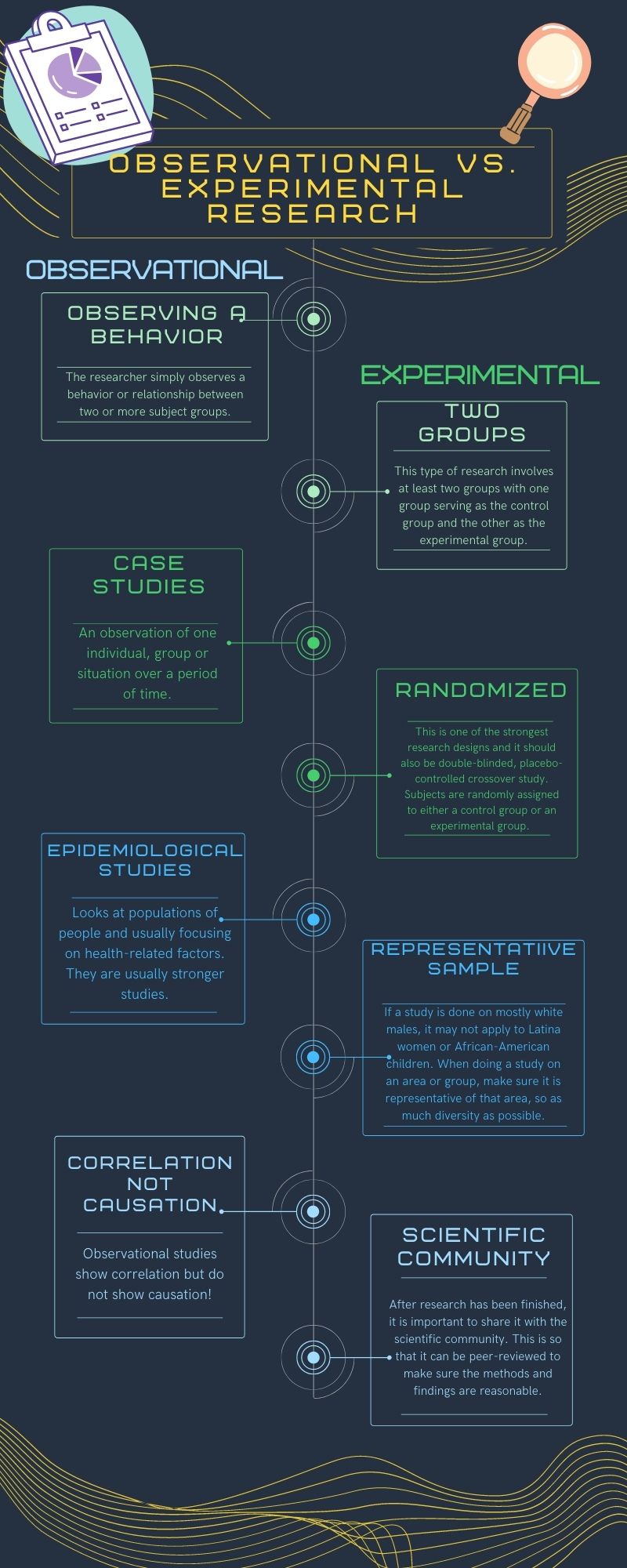

Nutrition research is based on the scientific method. The scientific method begins with a researcher generating a question from observations and coming up with a hypothesis for that question. A researcher can use observational or experimental methods to test the hypothesis.

Observational research means that the researcher simply observes a behavior or relationship between two variables. Examples of observational studies are case studies and epidemiological studies. A case study is the observation of one individual, group or situation over a period of time, whereas an epidemiological study looks at populations of people, usually focusing on health-related factors. Epidemiological studies are generally more rigorous than case studies because they involve larger groups of people but because these studies are observational they lack control over all of the variables which means that the results must be interpreted with that in mind. Observational studies show correlation – not causation.

Experimental research involves at least two groups of subjects with one group serving as a control group and the other(s) as the experimental group. The best types of experimental studies will have strong research design and will control for all variables that may affect the outcome of the study. For example, if a study is comparing the effect of different types of fat on cholesterol levels, the study should control for other factors, such as exercise, fiber or alcohol intake, and medications that may affect cholesterol levels. The strongest research design is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. There should be a large enough population to be able to detect statistical significance and the characteristics of the participants (age, sex, ethnicity, training status) should be similar. In a randomized experimental study, the participants are randomly assigned to either a control group or an experimental group. The experimental group is given a treatment and the control is not. For example, if a supplement was being tested, the experimental group would get the supplement and the control would get a placebo that looks, smells, and tastes just like the supplement. The study is blind if participants don’t know if they received the supplement or the placebo. In some situations, the scientist administering the treatments also does not know which group is getting each treatment. This is a double-blind study and in this case a third party is overseeing the research. After completion of the study, the third party will reveal which group received the treatment and which group received the placebo. If the study has a crossover design, then all of the subjects will receive both the placebo and the treatment. For example, if two trials were scheduled, subjects would complete one placebo trial and then “crossover” and complete one treatment trial. Participants would be randomized to receive either the placebo or treatment first. The purpose of having all of the elements in a study is to reduce bias. If the subjects knew they were receiving the treatment then they might try harder or if the scientist knew they might inadvertently encourage the subjects because they want the supplement to work.

Figure 1.4 Observational vs Experimental Research

For ethical reasons, most long term nutrition research is observational. As we said earlier, this means that we can see correlation between different dietary factors and risk of disease, but observational studies cannot tell us without a doubt that one factor “causes” disease. The exception to this is deficiency diseases that were discussed earlier in this chapter. However, because long term nutrition research is observational, we can identify dietary patterns associated with chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and certain types of cancers. Keep this in mind the next time you see an attention grabbing headline that claims a certain food causes cancer – even if they cite a study, the study was likely observational and the findings may be taken out of context.

For experimental research, it is important to pay attention to who the participants in the study were. For example, if the research was conducted on young white men, can the results be translated to middle aged Latina women? Sometimes, but not all the time. Historically, most research has been conducted on white men. In sports nutrition or supplement research, nearly all participants are college aged men. Recently, it was estimated that up to 80-90% of participants in clinical drug trials for new medications in the US are white. This lack of diversity in research is likely one of the reasons why there are such large disparities in regard to health outcomes between ethnic groups.

Red Flags of Nutrition Misinformation

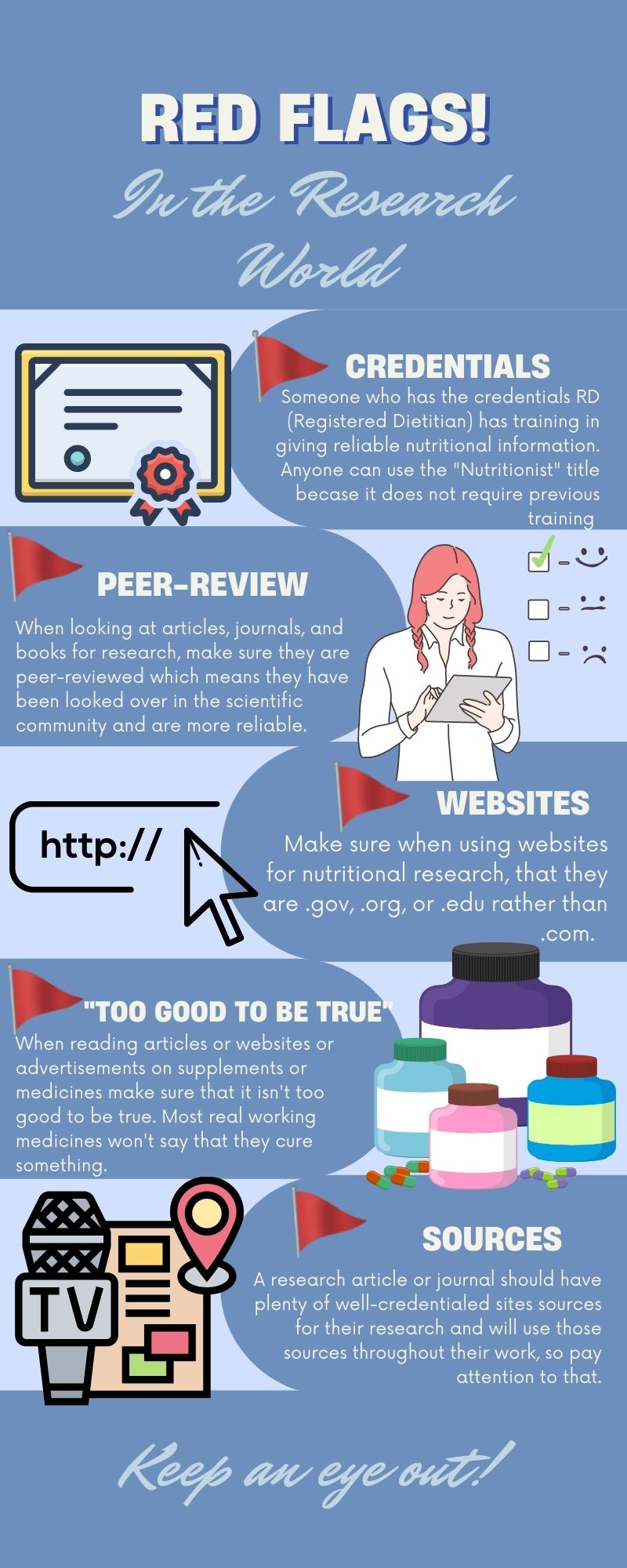

As we discussed earlier, we are all bombarded with nutrition information on a daily basis. Some of this information is accurate, but much of it is inaccurate or even harmful. With so many sources of information available, how do we know what or who to trust?

In the United States, a registered dietitian (RD) is the credential that indicates an individual has extensive training in nutrition. An RD has completed at least a bachelor’s degree in nutrition at an accredited university or college in the United States. In 2024, the minimum education requirement will be a master’s degree. The educational program will have incorporated specific course work in biochemistry, nutrition science, food service, counseling, medical nutrition therapy, and food science that has been reviewed and approved by the accrediting body of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. After completing their coursework, individuals must apply and be accepted to a 9-12 month supervised practice experience called a dietetic internship. The final step in becoming an RD is passing a national licensing exam administered by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. In order to maintain their credentials, RD’s must also participate in regular continuing education to remain current in the field. Historically, the credential RD has been used but dietitians now have the option to identify as either an RD or a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist (RDN). There is no difference in the training, scope of practice, or skill set of an RD versus an RDN.

What about nutritionists? There is no national licensing or accreditation body regulating who can and who cannot call themselves a nutritionist. A nutritionist may or may not be educated in nutrition. A personal trainer or health coach who also has an advanced degree in nutrition might provide reliable nutrition information. However, the trainer or coach may have only completed one course in nutrition, read a book on nutrition, or just enjoys researching nutrition information online and has no formal training. All of these people may call themselves a nutritionist, but they may not claim to be an RD. Anyone can use the term nutritionist because it does not require any degree or other qualification. Therefore, if someone claims to be a nutritionist, you should ask further questions about their training in nutrition before citing them as a reliable source of nutrition information.

Physicians are brilliant and talented members of our healthcare teams and have extensive training in medicine. However, nutrition education is largely absent from physician education programs. An individual applying to medical school is not required to complete any pre-requisite nutrition courses. During the 4 years of medical school physicians receive an average of 19 hours of training in nutrition, most of which is focused on biochemistry and rare vitamin deficiencies (2). After medical school, physicians often complete 3-7 years of training in residency and fellowship programs but there is no required nutrition component to this post-graduate training. Physician assistant and nursing programs also provide very minimal training in nutrition. There are some physicians, physician assistants, and nurses who do go out of their way to receive training in nutrition so they can provide credible nutrition information, but many primary care providers do not have a strong background in nutrition.

Figure 1.5 Red Flags of Nutrition Research

Media Attributions

- Observational vs. Experimental Research © Natalie Fox is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Red Flags © Natalie Fox is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license