1.6 Introduction to Physical Activity

Every time you move a part of your body you are participating in physical activity. Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement that is produced by skeletal muscles and requires energy expenditure (calories “burned”). Many people use the words physical activity and exercise interchangeably. However, exercise is just one type of physical activity.

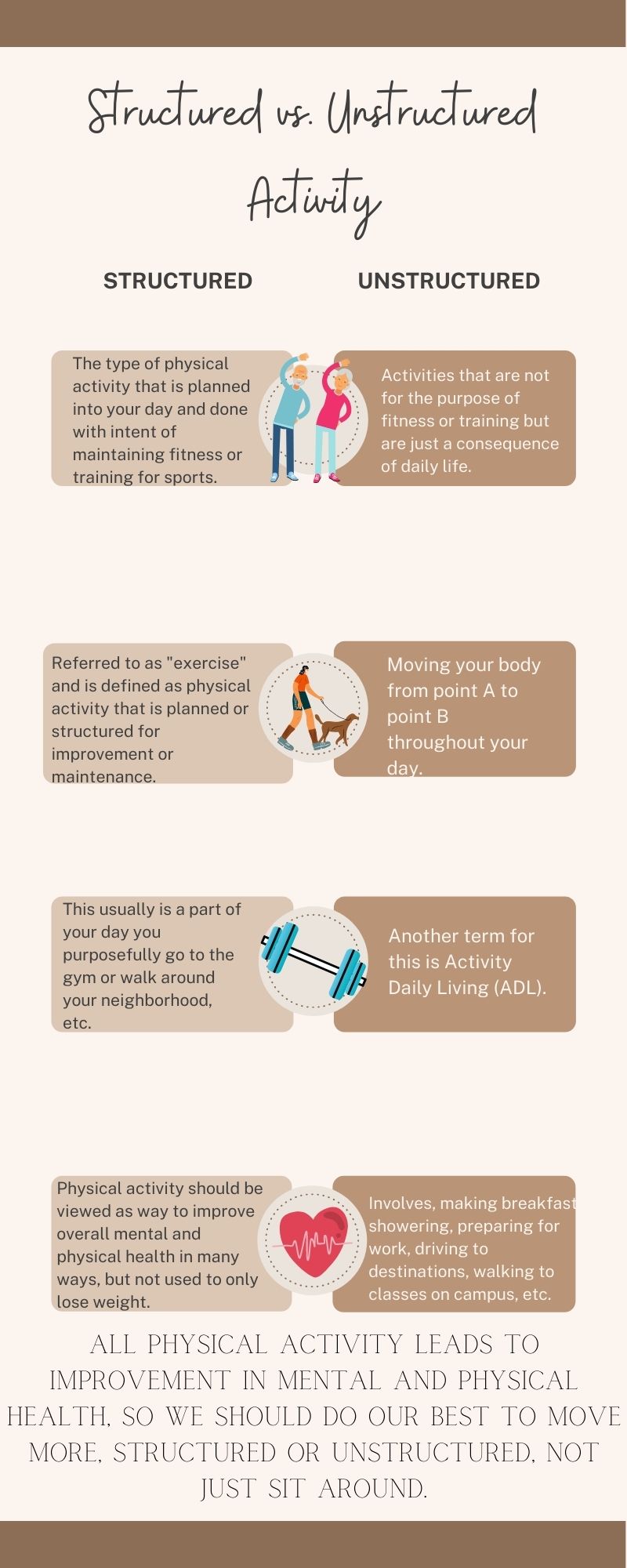

Some types of physical activities are structured and planned into your day and done with the intent of maintaining or improving fitness or training for a sport. This type of physical activity is referred to as structured activity. This is what we traditionally think of as “exercise” and is performed with the goal to improve or maintain one or more components of physical fitness. You also move your body just to get from point A to point B throughout your day. Showering, making breakfast, getting dressed, driving to work, mixing a cake, or raking leaves are also types of physical activity. However, because these activities are not for the purpose of fitness or training but are just a consequence of daily life, they are referred to as unstructured activities or activities of daily living (ADLs). You burn calories through all types of physical activity. If structured exercise is not something you enjoy, you can gain many of the same health benefits by doing unstructured activities. The most important thing is finding a sustainable way to move your body that you enjoy.

Figure 1.8 Structured vs. Unstructured Activity

Physical activity has many benefits beyond calorie burning and weight loss. Regular participation in exercise may improve an individual’s physiological, cognitive, and psychological health and reduce systemic inflammation in the body. Many decades of research illustrate the positive effect physical activity has on the body and mind. When practiced across the lifespan, physical activity may result in greater overall health, and a reduced risk for many chronic diseases. In fact, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) has created a program called Exercise is Medicine to encourage physicians and other healthcare providers to include physical activity in patient treatment plans and to refer patients to appropriate exercise professionals. The following is a list of some of the many benefits that regular physical activity (both structured and unstructured) can provide:

- Reduces risk of premature death

- Reduces risk of cardiovascular disease

- Reduces risk of diabetes

- Reduces risk of hypertension

- Improves cholesterol levels

- Reduces risk of strokes

- Reduces risk of certain types of cancer

- Improves bone health and prevents osteoporosis

- Improves joint health and may effectively treat symptoms of arthritis

- Improves ability to maintain a healthy body weight

- Reduces risk of Alzheimers and age related cognitive disorders

- Improves brain function and academic performance

- Improves mood and self-esteem

- Reduces stress and anxiety

- Reduces risk of mild to moderate depression (may also be used in the treatment of severe depression)

- Improves immune function

- Improves quality of sleep

- Improves longevity and quality of life

Despite the aforementioned benefits to people of all ages and races, many Americans do not meet recommendations for physical activity participation. Currently, only 53.3% of American adults meet the recommended guidelines for aerobic activity and 23.3% meet the guidelines for both aerobic and muscular strengthening activities (4). College students in particular may face unique challenges to participating in regular physical activity, often due to perceived and environmental barriers.

Sedentary behavior is defined as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs), while in a sitting, reclining or lying posture (5). This means that any time you are sitting or lying down doing a low energy activity you are engaged in sedentary behavior, with the exception of sleep. Sleep is not considered a sedentary behavior. Some common sedentary behaviors include sitting in a car or other form of public transportation, reading, and screen time (TV, computer, video games, or phone).

Reducing sedentary behavior is a key factor in preventing chronic disease and can influence overall risk of mortality. Research investigating the impact of sitting on all-cause mortality and risk factors for chronic disease has shown that periods of prolonged, uninterrupted sitting increased all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality risk and that the increased risk remained even when accounting for exercise. Additionally, the longer you sit uninterrupted, the greater your risk whereas breaking up sedentary time lowers your risk. In other words, even if you go to the gym before or after work or school, if you sit at a desk all day you still have an increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. The exercise does not counteract the full day of sitting.

What this means is that, in order to improve your health, the first thing you should do is sit less. If you have an occupation that requires you to sit all day, take short breaks every hour and walk around for several minutes. Try to increase your unstructured physical activity by building light activities into your schedule. For example, take the stairs instead of the elevator, walk or bike (if possible) instead of driving, walk the dog instead of putting it in the yard. By just increasing the amount of daily activity you do, you can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing, and dying from, chronic disease. If you have a fitness tracker or smart watch, you can have it alert you if you’ve been sitting too long and use that as a reminder to get up and move for a few minutes.

Next, increase your daily amount of structured activity. There are five basic components of fitness, and it is recommended that you include activities that address each one.

- Cardiorespiratory (Aerobic) Endurance: The ability to perform prolonged, dynamic exercise using large muscle groups at a moderate-to-high-intensity level.

- Body Composition: The proportion of fat and fat-free mass (muscle, bone, and water) in the body.

- Muscular Strength: The amount of force a muscle can produce in a single maximum effort.

- Muscular Endurance: The ability to resist fatigue and sustain a given level of muscle tension, or repeated muscle contractions against resistance for a given time period.

- Flexibility: The ability to move the joints through their full range of motion.

Media Attributions

- Structured vs. Unstructured Activity © Natalie Fox is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license