1.7 Designing a Structured Exercise Program

Though there are many health benefits of simply incorporating more unstructured movement in your life, if you are looking to improve your fitness you need a structured exercise program. There are five basic training principles that should be included in a good structured exercise program: progressive overload, individuality, specificity, recovery, and reversibility.

- Progressive overload refers to the idea that in order to see progress, you must continue to challenge yourself by increasing the frequency, duration, or intensity of your training. At the beginning of your training program, it may be challenging to run one mile at a 10 minute/mile pace on the treadmill. However, as you improve, you will need to either run faster, run a longer distance, or run a course with more hills to continue to challenge your body.

- The principle of individuality means that each person is unique and there is no one size fits all best way to train. Figure out what works best for your body. Do you need more recovery than others? Are there injuries you need to work around? Take your individual circumstances into account when planning an exercise program.

- The principle of specificity refers to the idea that you need to do specific exercises to improve a specific aspect of your fitness. If your goal is to train for a marathon, your training program should include long distance running. If you only lift weights and train sprints, you are doing the wrong type of exercise for your goal of completing a marathon.

- The recovery principle, also known as the hard/easy principle, means that if you train intensely, you must give your body adequate rest. These rest periods allow your body to adapt to the stress of training. Athletes who do not allow their bodies to recover between workouts are at risk of overtraining syndrome which can lead to injury and poor physical performance.

- Reversibility or “use it or lose it” means that when you stop exercising, you lose the effects of training. This could be due to taking a break from training because of illness or injury.

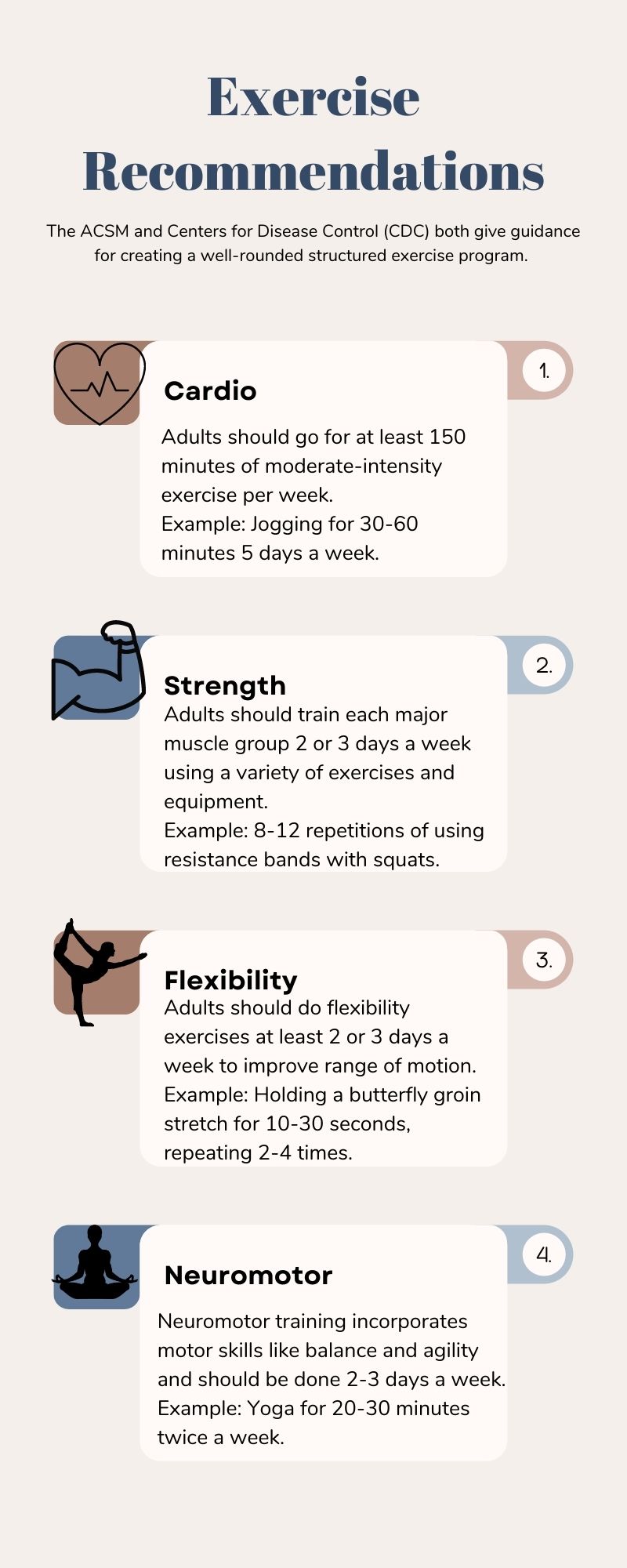

The ACSM and Centers for Disease Control (CDC) both provide guidance for creating a well-rounded structured exercise program. Both sets of guidelines make recommendations for cardiovascular and strength training. However, the ACSM guidelines are more comprehensive and include recommendations to meet the basic training principles described above. For this class, we will use the ACSM guidelines which are described below. The four areas the ACSM guidelines address include cardiovascular, strength, flexibility, and neuromotor training.

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular exercise or cardio is exercise that depends on aerobic energy generating processes that rely on the cardiovascular system to deliver oxygen to exercising muscles. This type of exercise involves repeatedly contracting your major muscle groups and increases your heart rate. Some examples of cardiovascular exercise include running, walking, hiking, swimming, biking, jump rope, calisthenics, and dance. It is important to note that while cardiovascular exercise involves an increase in heart rate, not all activities that increase your heart rate should be considered “cardio.” For example, fear and stress and evoke a heart rate response. Watching scary movies may increase your heart rate but is not considered a replacement for cardio. At the same time, many people combine cardio and strength training by participating in crossfit or certain types of high intensity interval training. This can work if you are actively moving your body. However, if you are just lifting weights and your heart rate is elevated during your set, sitting and resting while waiting for your heart rate to come down is not considered cardio because your muscles are not contracting and you are not gaining the muscle adaptations that regular cardiovascular exercise provides. If your heart rate does not recover between sets of heavy lifts, that could be a sign that your cardiovascular system needs more conditioning.

ACSM Recommendation:

- Adults should get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week.

- Exercise recommendations can be met through 30–60 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise (5 days per week) or 20–60 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise (3 days per week).

- Exercise recommendations can be met through 30–60 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise (5 days per week) or 20–60 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise (3 days per week).

- Gradual progression of exercise time, frequency, and intensity is recommended for best adherence and least injury risk.

- People unable to meet these minimums can still benefit from some activity.

Exercise “snacks” and high intensity training

New research suggests that sedentary individuals can gain many benefits of cardio from short bouts of high intensity exercise, also called “exercise snacks.” These exercise snacks can be < 1 minute to 5 minutes in length and involve breaking up long stretches of sitting to do high intensity exercise such as sprinting up 3 flights of stairs or doing jumping jacks for 1 minute as fast as you can. The benefit of this type of activity is that even less time is required to gain some cardiovascular benefits which is appealing for those who do not participate in recommended levels of physical activity due to limited time. Also, an individual can participate in an “exercise snack” in their home or workplace without having to change and drive to a gym. The jury is still out on if these high intensity “exercise snacks” are better than breaking up your day with 10 minute walking breaks; but the time commitment for high intensity “exercise snacks” is less and as time is a major factor in Americans’ lack of activity, this is something worth considering adding to your routine if you struggle with getting enough cardiovascular exercise.

Strength

Strength training includes activities that build muscular strength and endurance and increase muscle mass. Strength training can be performed with weights or bodyweight exercises. In order to build muscle mass, an individual must 1) have a surplus of calories (see chapter 3) and 2) practice progressive overload as described above. In addition to increasing muscle mass, strength training is important for improving bone density and reducing risk of fracture. Strength training is important for individuals of any age, but can be especially beneficial for improving or maintaining quality of life as one ages.

ACSM Recommendation:

- Adults should train each major muscle group 2 or 3 days each week using a variety of exercises and equipment.

- Very light or light intensity is best for older persons or previously sedentary adults starting exercise for the first time.

- Two to four sets of each exercise will help adults improve strength and power.

- For each exercise, 8 – 12 repetitions improve strength and power, 10 – 15 repetitions improve strength in middle-age and older persons starting exercise, and 15 – 20 repetitions improve muscular endurance.

- Adults should wait at least 48 hours between resistance training sessions on the same muscle group.

Flexibility

Flexibility training includes activities that improve the mobility of joints, ligaments, and tendons. This is the most ignored area of fitness but flexibility is important for reducing injury risk. When people think of flexibility training, they often think of static stretching. This is one way to work on flexibility, but other dynamic activities such as yoga, barre, tai chi, or even foam rolling can help improve mobility and range of motion.

ACSM Recommendation:

- Adults should do flexibility exercises at least 2 or 3 days each week to improve range of motion.

- For static stretching, each stretch should be held for 10 – 30 seconds to the point of tightness or slight discomfort.

- Repeat each stretch two to four times, accumulating 60 seconds per stretch.

- Flexibility exercise is most effective when the muscle is warm. Try light aerobic activity or a hot bath to warm the muscles before working on flexibility.

Neuromotor

Many people have not heard of neuromotor training, but this is the type of exercise that relates directly to real life activities. It incorporates motor skills such as balance, agility, coordination, and gait and is referred to as functional training. Some examples include: Pilates, Yoga, barre, tai chi, and CrossFit or boot camp classes. Neuromotor training is not limited to these activities though. In fact, any activity that involves multiple joints or multiple muscle groups can be considered neuromotor exercise. Does a game of pickup basketball or ultimate frisbee involve agility and coordination? That counts. Do burpees, step ups, or squat to shoulder press involve coordination between multiple muscle groups? Those count too. Neuromotor training recommendations can often be met as part of your cardiovascular, strength, and flexibility routine. A lifetime of neuromotor activities can help prevent falls and improve quality of life in older adults.

ACSM Recommendation:

- Neuromotor exercise is recommended for 2-3 days per week

- 20-30 minutes per day

Figure 1.9 Exercise Recommendations

Media Attributions

- Exercise Recommendations © Natalie Fox is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license