Appendix A: Osteology

This chapter is a revision from “Appendix A: Osteology” by Jason M. Organ and Jessica N. Byram. In Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology, first edition, edited by Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera, and Lara Braff, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Learning Objectives

- Identify anatomical position and anatomical planes, and use directional terms to describe relative positions of bones and teeth.

- Describe the different regions of the human skeleton and identify (by name) all of the bones within them.

- Distinguish major bony features of the human skeleton like muscle attachment sites and passages for nerves and/or arteries and veins.

- Identify the bony features relevant to estimating age and sex in forensic and bioarchaeological contexts.

Introduction to Osteology

Osteology, or the study of bones, is central to biological anthropology because every person’s skeleton tells a story of how that person has lived. Bones from archaeological sites can be used to understand what animals people ate, how stressful and strenuous their lives were, and how they died—by natural or unnatural causes. This appendix introduces the basics of anatomical terminology and describes the different regions and bones of the skeleton. It also highlights some skeletal features that are used frequently by forensic anthropologists to estimate the age and sex of recovered remains. The authors note that sex is not binary but exists on a spectrum based on influences of chromosomes, genes, and hormones. These biological influences affect the size and shape of bone, which is sometimes useful in classifying skeletal remains into one of the two most common sex categories: female and male.

Bone Structure and Function

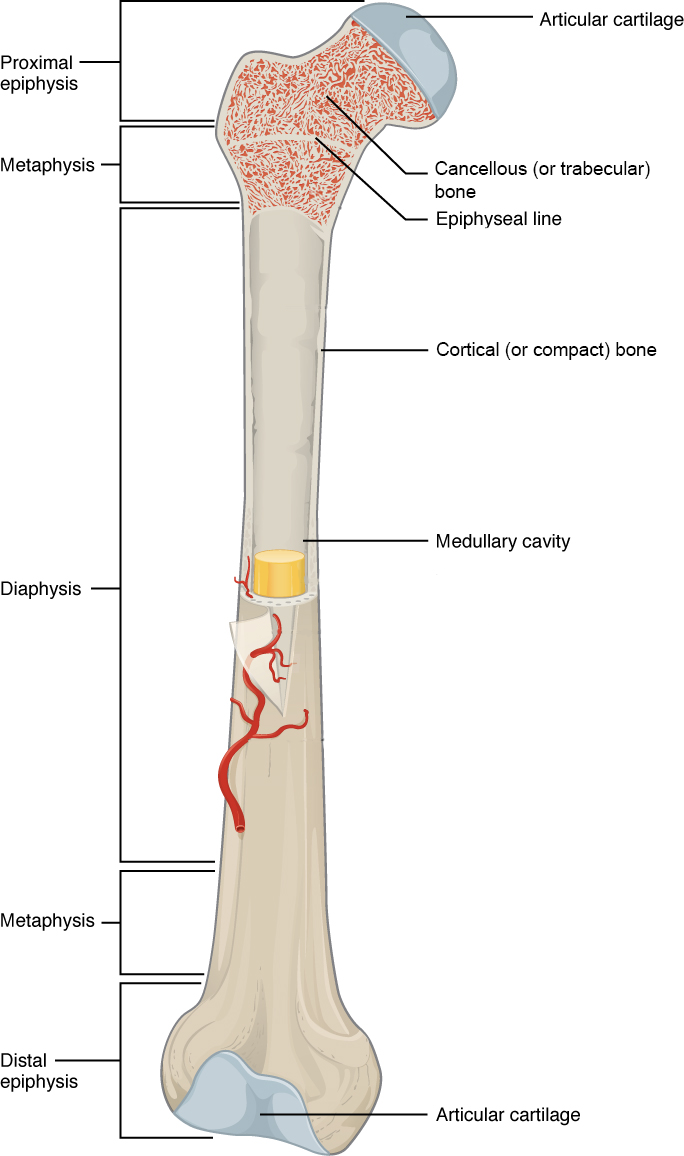

Bone is a composite of organic collagen and an inorganic mineral (hydroxyapatite, a calcium phosphate salt), which help make it strong enough to support the body under the force of gravity without collapsing. When bone is mature (fully mineralized as in adults), it comprises an outer dense region of bone called cortical (or compact) bone and an inner spongy region of bone called cancellous (or trabecular) bone (Figure A.1).

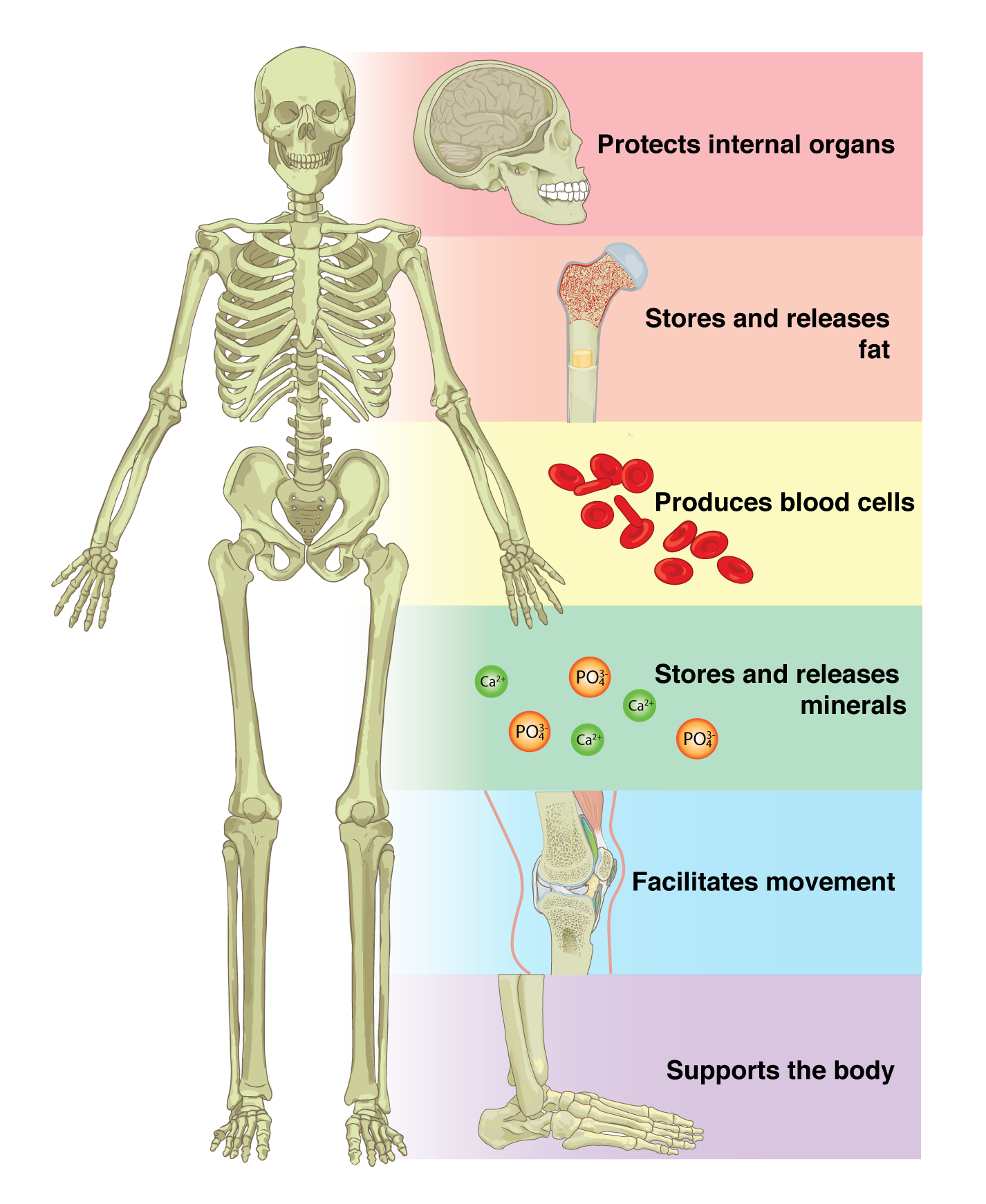

Bone performs both metabolic and mechanical functions for the body. On the metabolic side, bone is required to maintain mineral (i.e., calcium) homeostasis and for the production of red and white blood cells (Figure A.2), which develop in the diaphyseal marrow cavity and the cancellous region of the metaphysis and epiphysis. But it is undeniable that the mechanical functions of bone are primary because bone is critically responsible for protecting internal organs, providing support against the force of gravity, and serving as a network of rigid levers for muscles to act upon during movement.

Bone Shape

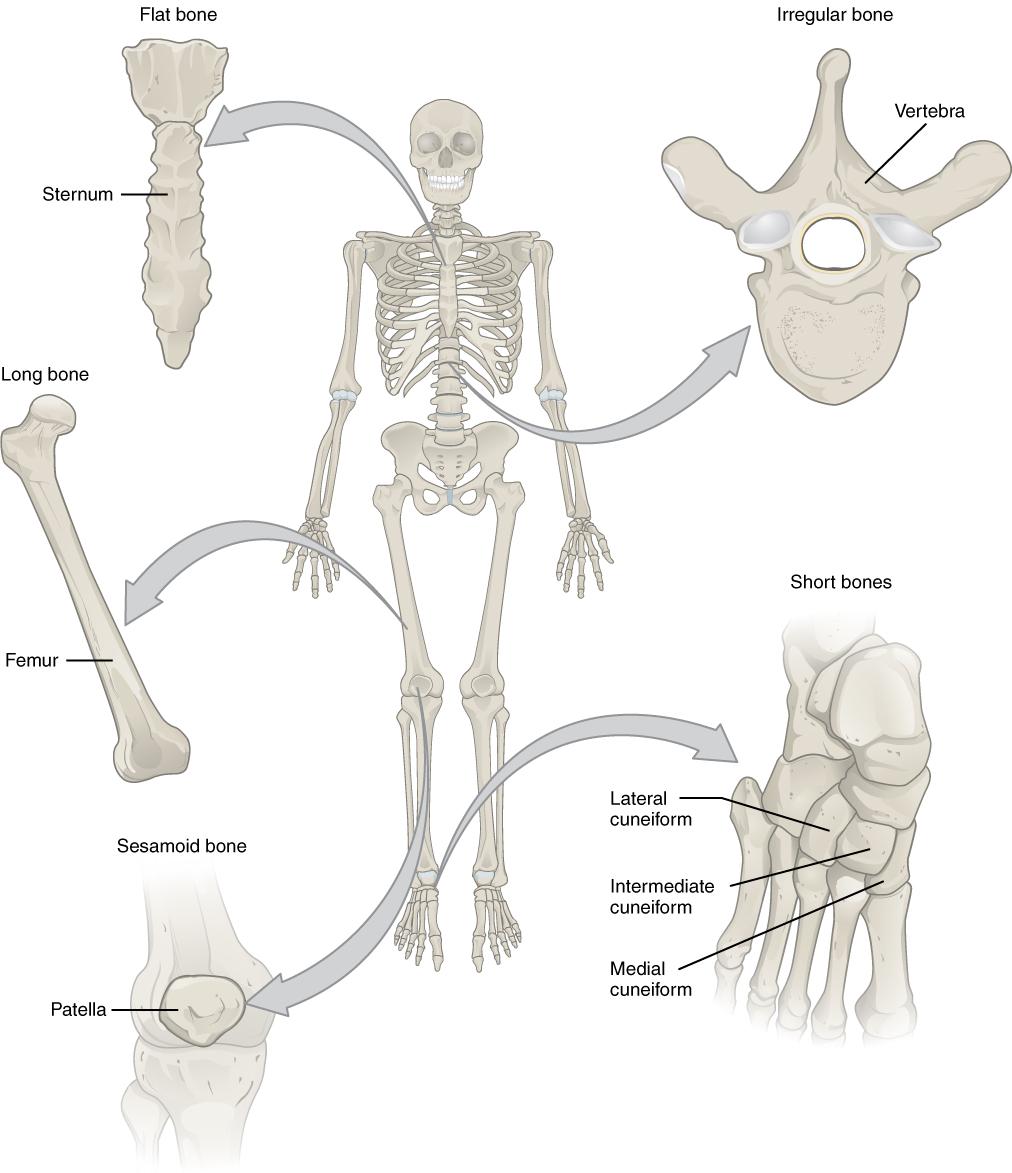

Bones have different shapes that largely relate to their specific function within the skeletal system. Additionally, the ratio of cortical to cancellous bone, and which muscles are attached to the bone and how, affect the shape of the whole bone. Generally there are five recognized bone shapes: long bones, short bones, flat bones, sesamoid bones, and irregular bones. Long bones are longer than they are wide and consist of three sections: diaphysis, epiphysis, and metaphysis (see Figure A.1). The diaphysis of a long bone is simply the shaft of the bone, and it comprises mostly cortical bone with a thin veneer of internal cancellous bone lining a medullary cavity. At both the proximal and distal ends of every long bone, there is an epiphysis, which consists of a thin shell of cortical bone surrounding a high concentration of cancellous bone. The epiphysis is usually coated with cartilage to facilitate joint articulation with other bones. The junction between diaphysis and epiphysis is the metaphysis, which has a more equal ratio of cortical to cancellous bone. Examples of long bones are the humerus, the femur, and the metacarpals and metatarsals.

The other three bone shapes are simpler. Short bones are defined as being equal in length and width, and they possess a mix of cortical and cancellous bone (Figure A.3). They are usually involved in forming movable joints with adjacent bones and therefore often have surfaces covered with cartilage. Examples of short bones are the carpals of the wrist and the tarsals of the ankle. Flat bones are flat and consist of two layers of thick cortical bone with an intermediate layer of cancellous bone referred to as diploë. Most of the bones of the skull are flat bones, such as the frontal and parietal bones, as well as all parts of the sternum (Figure A.3). Sometimes bones develop within the tendon of a muscle in order to reduce friction on the joint surface and to increase leverage of the muscle to move a joint. These types of bones are called sesamoid bones, and these include the patella (or knee cap) and the pisiform (a bone of the wrist). Irregular bones are bones that don’t fit into any of the other four categories. The shapes of these bones are often more complex than the others, and examples include the vertebrae and certain bones of the skull, like the ethmoid and sphenoid bones (Figure A.3).

Dig Deeper: Bone Functional Adaptation

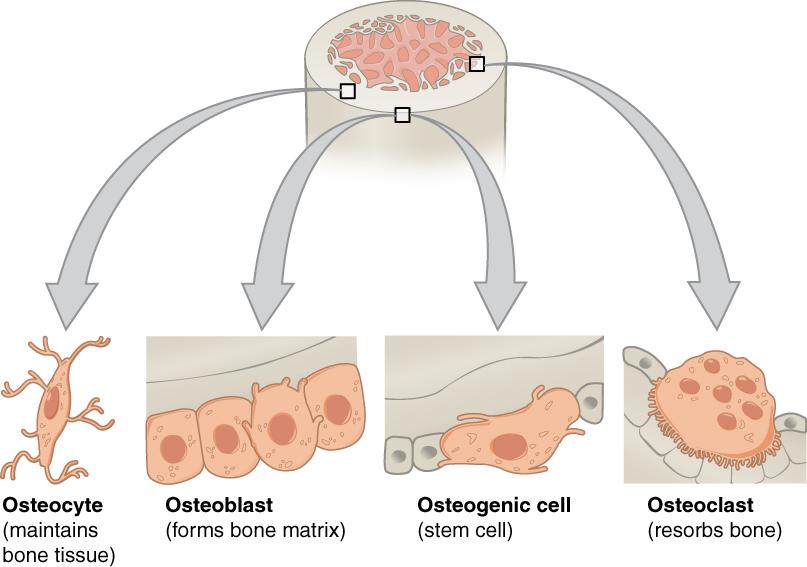

Each time we move our muscles, we bend, twist, compress, and tense our bones, and this causes them to develop microscopic cracks that weaken them. These may even lead to a bone fracture. Bone cells called osteocytes can sense when these microcracks form. Osteocytes then signal osteoclasts to remove the cracked bone and osteoblasts to lay down new bone—a process known as skeletal remodeling. Osteogenic cells are stem cells that are able to differentiate into osteoblasts and osteocytes (Figure A.4).

Did Deeper: How Do Bones Develop?

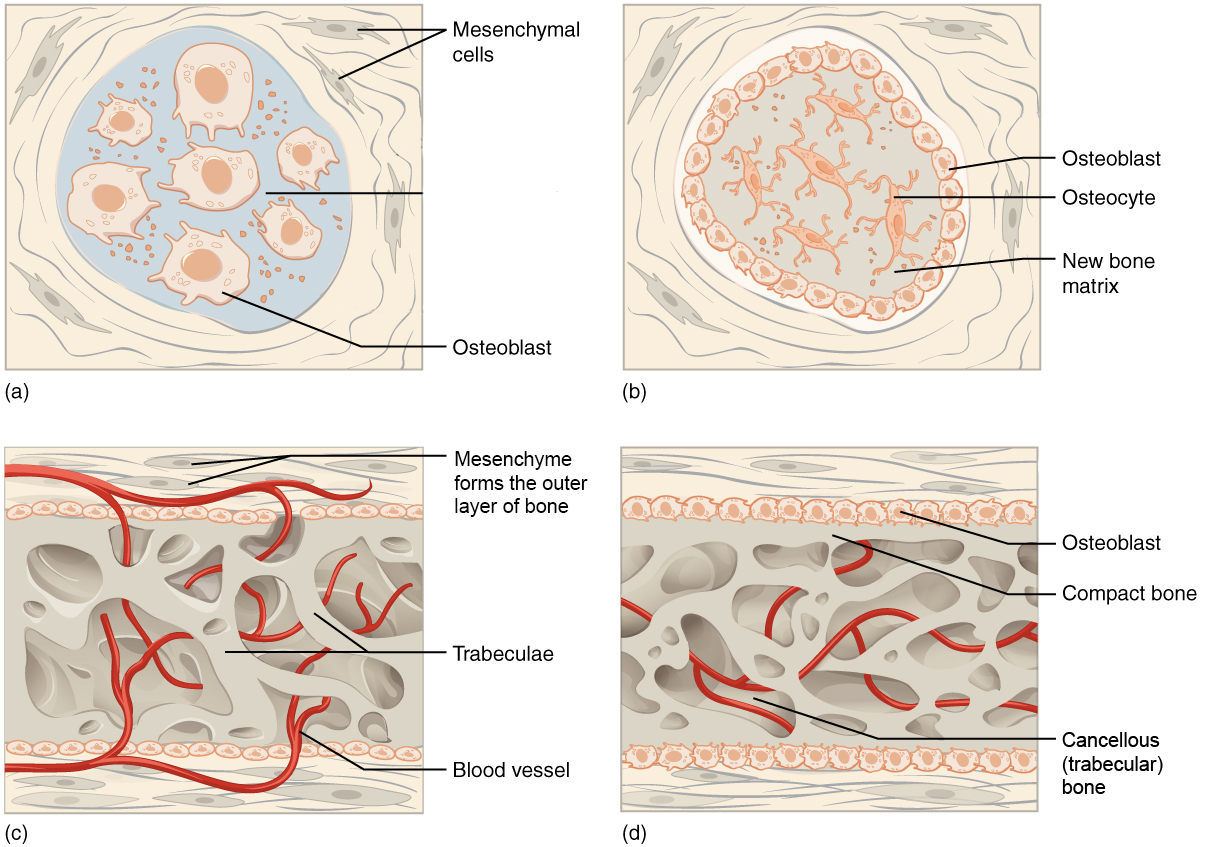

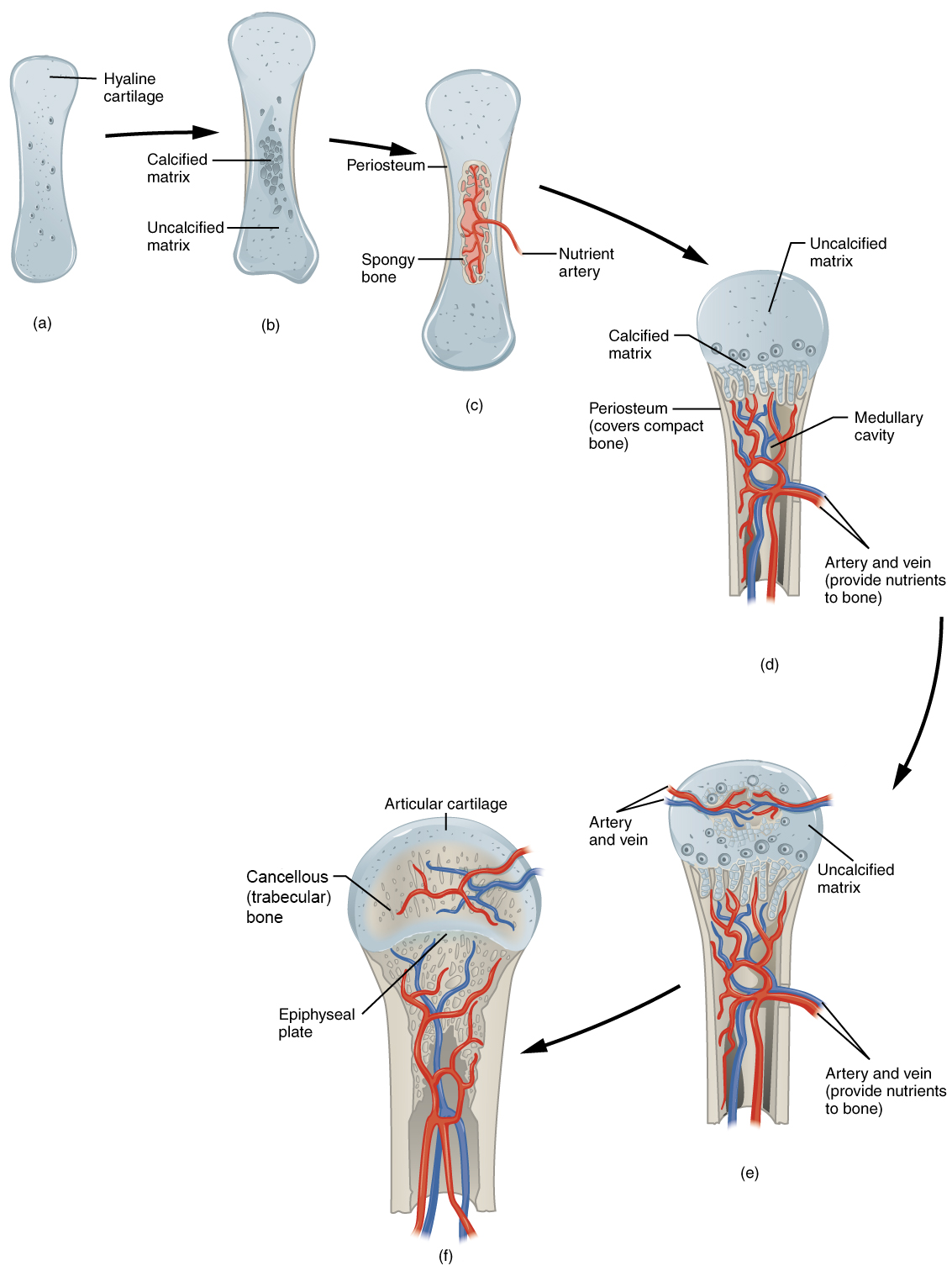

Bones develop via one of two mechanisms: intramembranous or endochondral bone formation. During intramembranous bone formation connective tissue (mesenchymal) stem cells form a tissue layer and then differentiate into osteoblasts, which begin to synthesize new bone along the tissue layer (Figure A.5). Only a few bones develop through intramembranous bone formation, mostly bones of the skull and the clavicle (collar bone). In endochondral bone formation, instead of developing directly from connective tissue stem cells, osteoblasts develop from an intermediate cartilage “model” that is then replaced by synthesized new bone (Figure A.6). Most bones of the skeleton develop through endochondral bone formation (Burr and Organ 2017).

Anatomical Terminology

Anatomical Planes

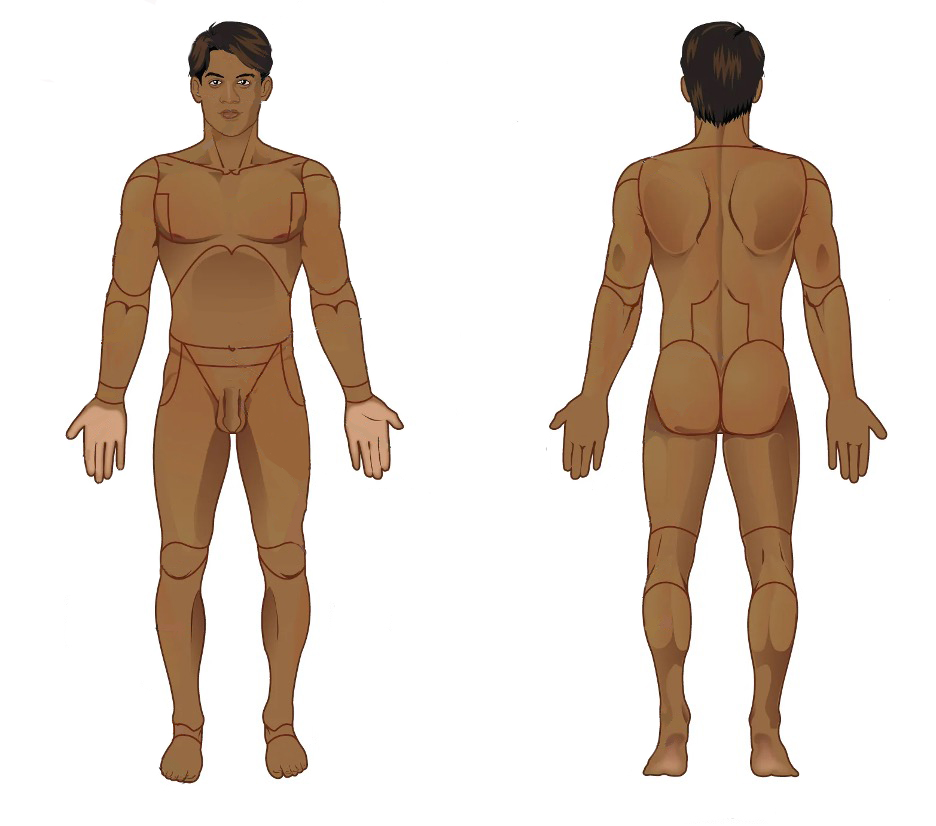

A body in anatomical position is situated as if the individual is standing upright; with head, eyes, and feet pointing forward; and with arms at the side and palms facing forward. In anatomical position, the bones of the forearm are not crossed (Figure A.7).

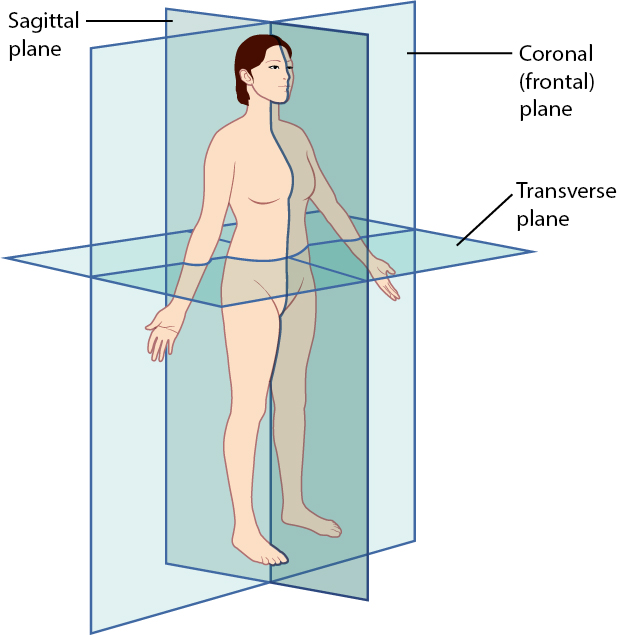

In anatomical position, specific organs are situated within specific anatomical planes (Figure A.8). These imaginary planes divide the body into equal or subequal halves, depending on which plane is described. Coronal (frontal) planes divide the body vertically into anterior (front) and posterior (back) halves. Transverse planes divide the body horizontally into superior (upper) and inferior (lower) halves. Sagittal planes divide the body vertically into left and right halves. The plane that divides the body vertically into equal left and right halves is called the midsagittal plane. The midsagittal plane is also called the median plane because it is in the midline of the body. Every other sagittal plane divides the body into unequal right and left halves; these planes are called parasagittal planes.

Directional Terms

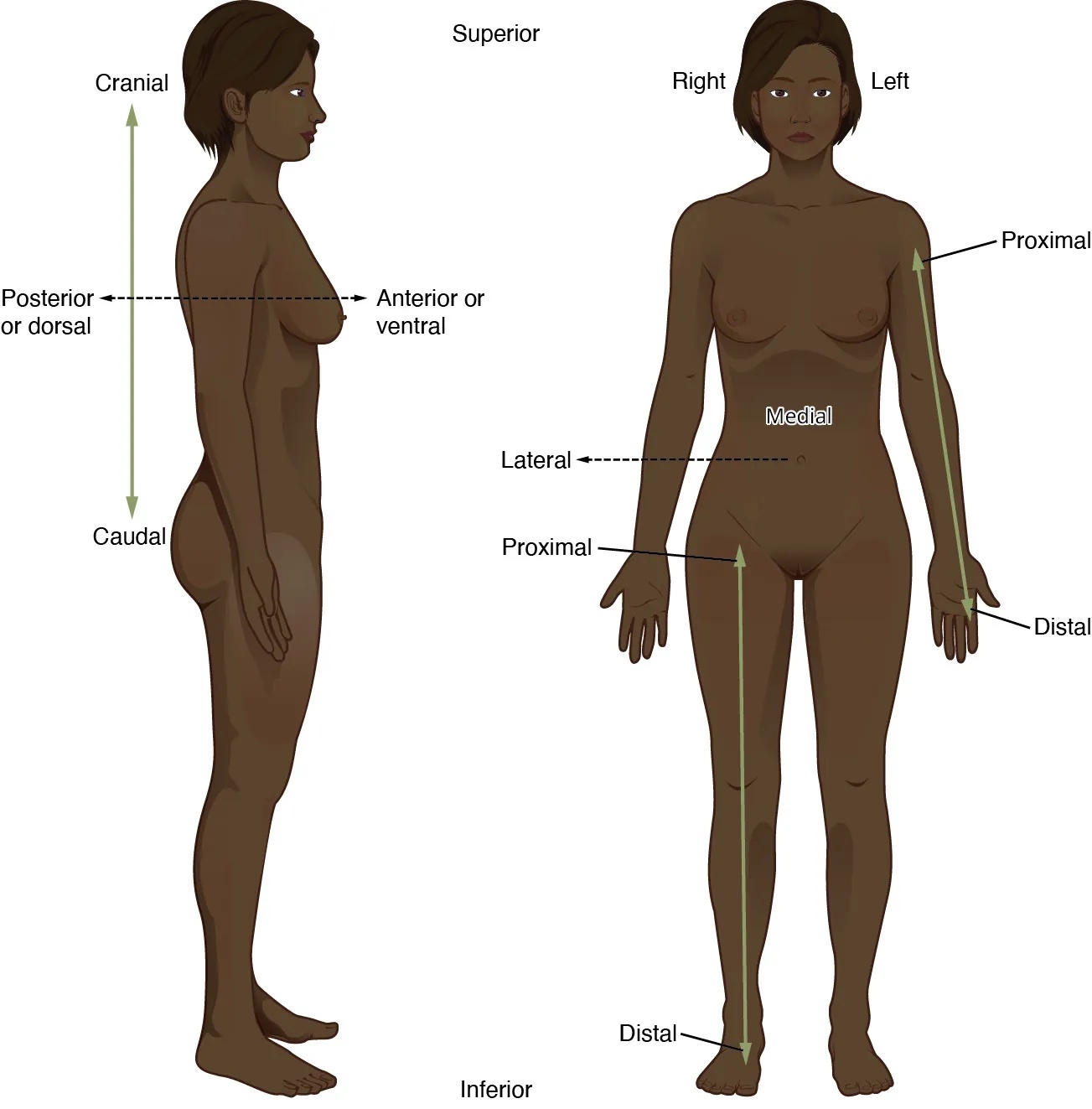

An anatomical feature that is anterior (or ventral) is located toward the front of the body, and a bone that is posterior (or dorsal) is located toward the back of the body (Figure A.9). For example, the sternum (breastbone) is anterior to the vertebral column (“backbone”). A feature that is medial is located closer to the midline (midsagittal plane) than a feature that is lateral, or located further from the midline. For example, the thumb is lateral to the index finger. A structure that is proximal is closer to the trunk of the body (usually referring to limb bones) than a distal structure, which is further from the trunk of the body. For example, the femur (thigh bone) is proximal to the tibia (leg bone). Finally, a structure that is superior (or cranial) is located closer to the head than a structure that is inferior (or caudal). For example, the rib cage is superior to the pelvis, and the foot is inferior to the knee.

Human Skeletal System

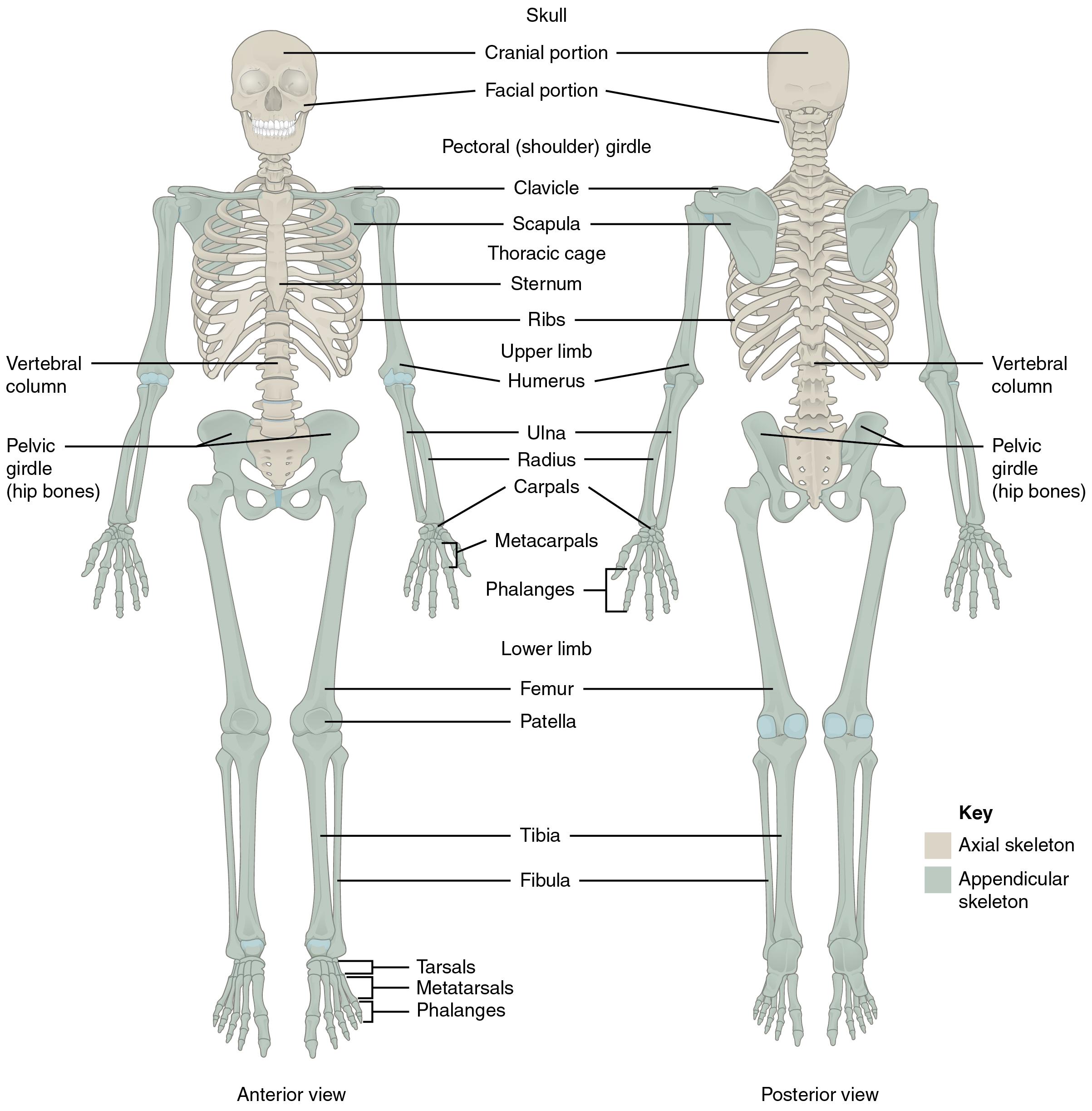

The skeletal system is divided into two regions: axial and appendicular (Figure A.10). The axial skeleton consists of the skull, vertebral column, and the thoracic cage formed by the ribs and sternum (breastbone). The appendicular skeleton comprises the pectoral girdle, the pelvic girdle, and all the bones of the upper and lower limbs.

Axial Skeleton

Skull

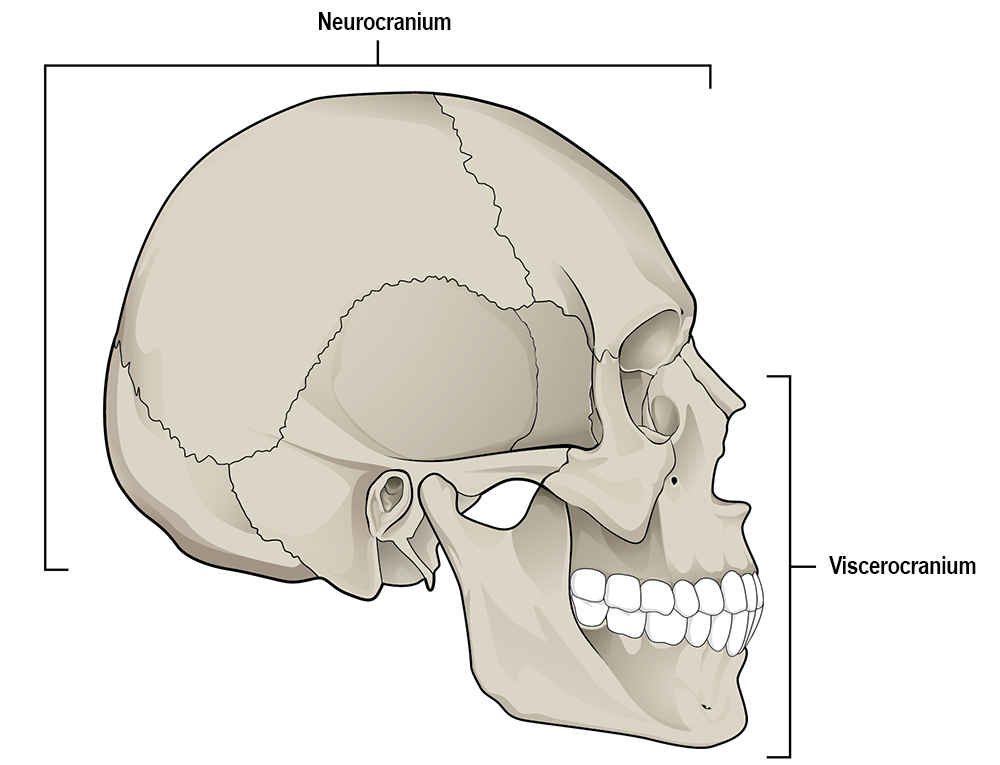

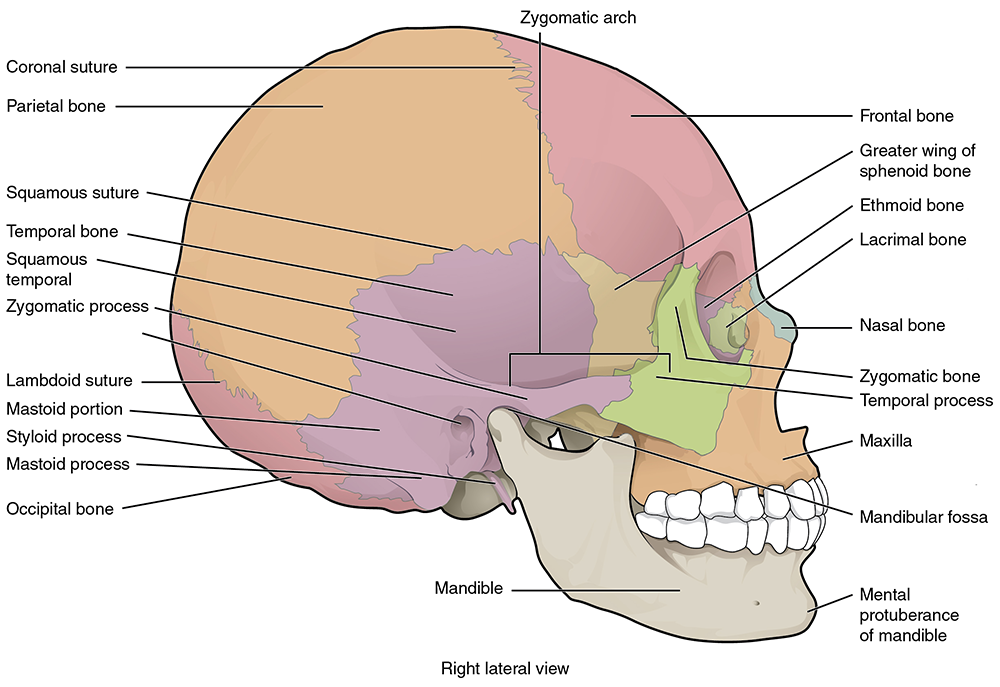

The skull comprises numerous bones (some paired and others that are unpaired) and is divided into two major portions: the mandible (or lower jaw) and the cranium (the remainder of the skull). The cranium is further subdivided into the neurocranium (or cranial vault), which houses the brain, and the viscerocranium (or facial skeleton; Figure A.11), which houses the organs responsible for special senses like sight, smell, taste, hearing, and balance.

Where two bones of the cranium come together, they form articulations called cranial sutures, which fuse (or close) with increasing age. Degree of suture closure can be used to broadly estimate age at death (Boldsen et al. 2002; Meindl and Lovejoy 1985).

Bones and Some Features of the Neurocranium

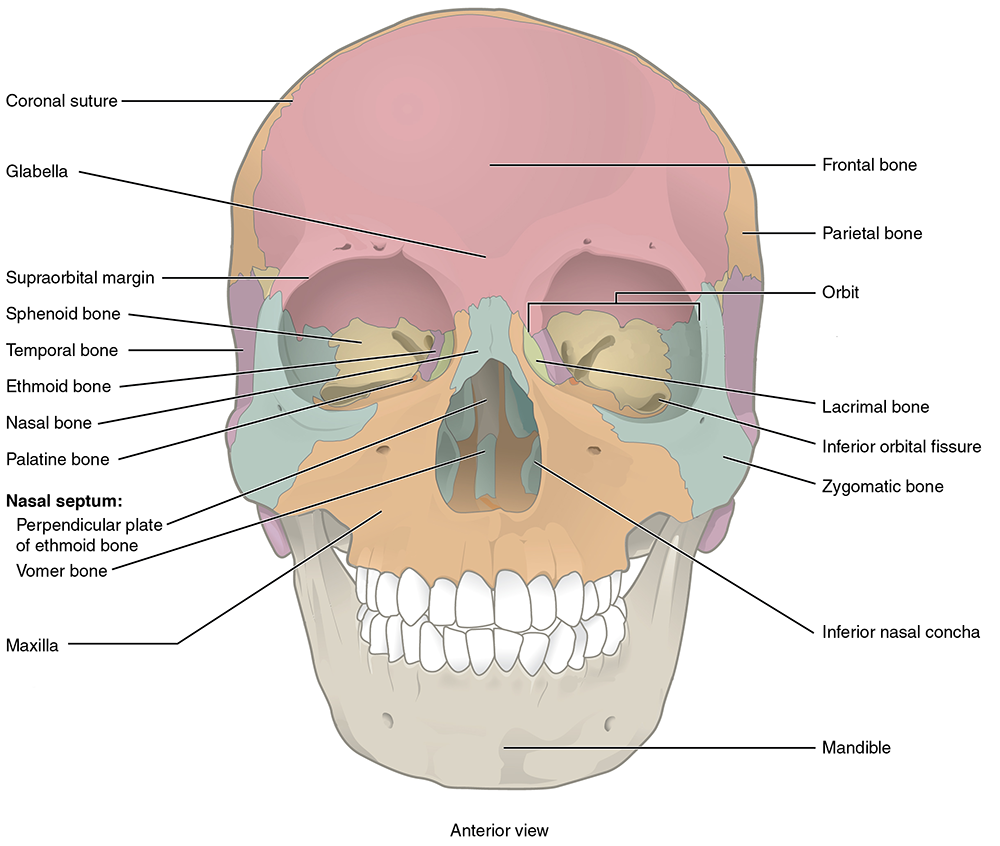

Frontal bone: an unpaired bone consisting of two parts: a superior, vertically oriented portion called the squama and an inferior, horizontally oriented portion that forms the roof of the orbit (eye socket; Figures A.12 and A.13).

The coronal suture is the articulation between the frontal bone and the two parietal bones posterior and lateral to the frontal.

The frontal bone develops initially as two separate bones that fuse together during growth. Occasionally this fusion is incomplete, resulting in a metopic suture that persists between the two halves (left and right) of the frontal bone (Cunningham, Scheuer, and Black 2017).

The glabella is a bony projection between the brow ridges. The glabella in females tends to be flat while it is more rounded and protruding in males (Walker 2008).

The supraorbital margin is the upper edge of the orbit. The thickness of the edge may be used as an indicator of sex. The border tends to be thin and sharp in females and blunt and thick in males.

Parietal bone: Paired bones that form the majority of the roof and sides of the neurocranium (Figures A.12 and A.13).

The sagittal suture is the articulation between the right and left parietal bones. It extends from the coronal suture to the lambdoidal suture, which separates the parietal bones from the occipital bone posteriorly.

Each parietal bone is marked by two temporal lines (superior and inferior), which are anterior-posterior arching lines that serve as attachment sites for a major chewing muscle (temporalis) and its associated connective tissue.

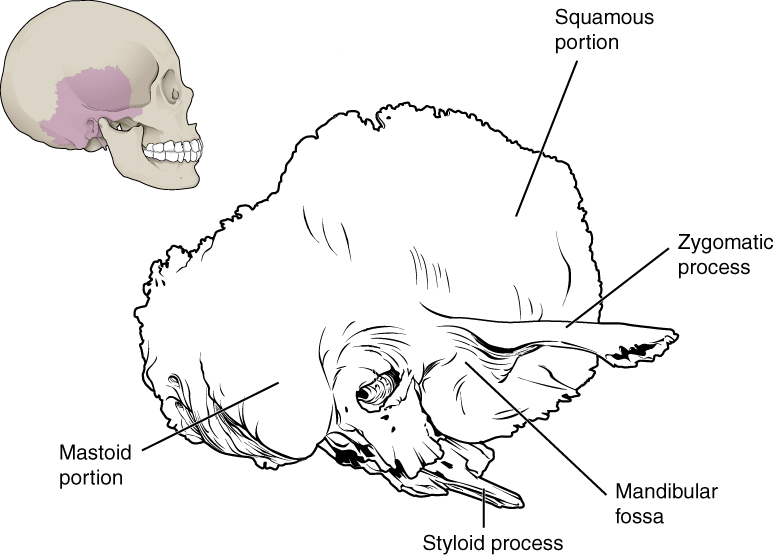

Temporal bone: Paired bones on the lateral side of the neurocranium that are divided into two portions: squamous (or flat) portion that forms the lateral side of the neurocranium and the petrous (or rock-like) portion that houses the special sense organs of the ear for hearing and balance as well as the three tiny bones of the middle ear: incus, malleus, and stapes (Figures A.13, A.14, and A.15).

The squamosal suture is the articulation between the squamous portion of the temporal bone and the inferior border of the parietal bone.

The mastoid process is a prominent muscle attachment site for several muscles including the large sternocleidomastoid muscle. Males tend to have longer and wider mastoid processes compared to females (Walker 2008).

The styloid process is a thin, pointed, inferior projection of the temporal bone that serves as an attachment site for several muscles and a ligament of the throat.

The zygomatic process of the temporal bone is a long thin, arch-like process that originates from the squamous portion of the temporal bone. The zygomatic process articulates with the temporal process of the zygomatic bone to form the zygomatic arch (or cheekbone).

The mandibular fossa is the depression in the temporal bone where the mandibular condyle (see below, under mandible) articulates to form the temporomandibular (or jaw) joint.

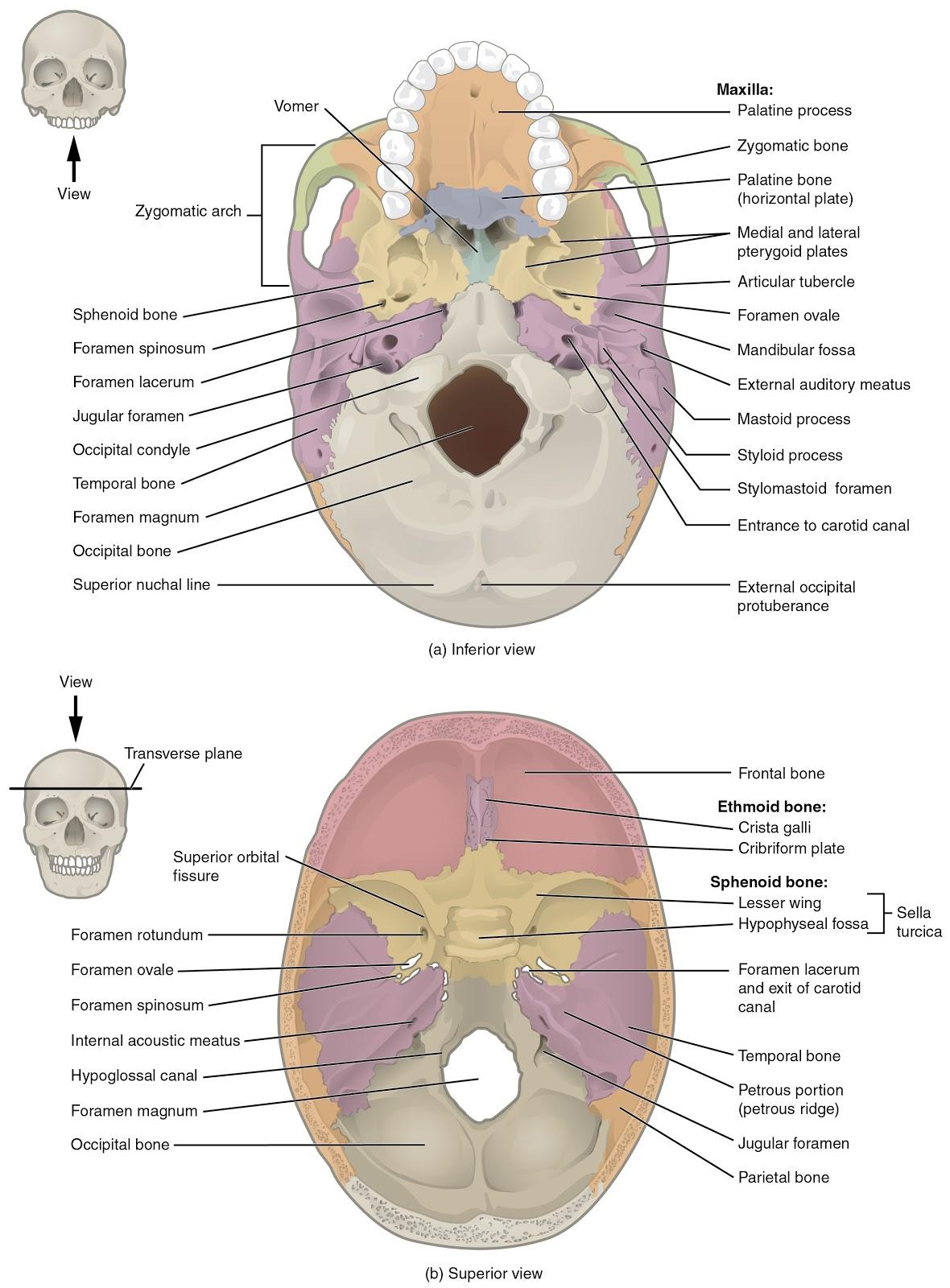

Occipital bone: Unpaired bone that forms the posterior and inferior portions of the neurocranium (see Figures A.13 and A.15).

The lambdoidal suture is the articulation between the occipital bone and the two parietal bones. It resembles the shape of the Greek letter lambda.

The external occipital protuberance (EOP) is a bump along the posterior margin of the occipital bone where the nuchal ligament attaches.

The nuchal lines are parallel ridges that meet on the midline at the EOP and serve as attachment sites for neck muscles. Nuchal lines are usually more pronounced in males.

The occipital bone contains a large circular opening called the foramen magnum, which provides a space for passage of the brainstem/spinal cord from the neurocranium into the vertebral canal of the spine.

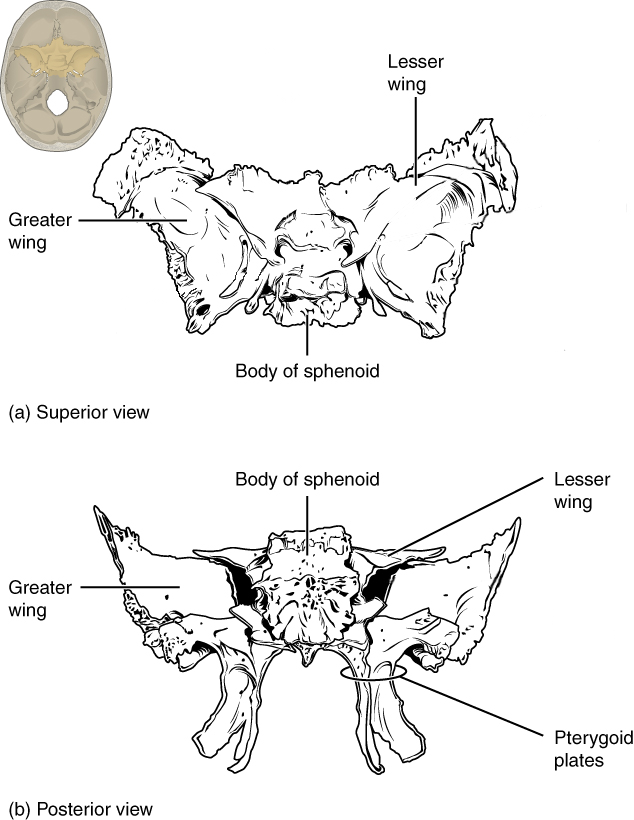

Sphenoid bone: Unpaired, butterfly-shaped bone that forms the central portion of the bottom of the neurocranium. The sphenoid is divided into several regions, including the body, greater wings, lesser wings, and pterygoid processes (with pterygoid plates; see Figures A.15 and A.16). This bone is critical to supporting the brain and several nerves and blood vessels supplying this region.

Pterygoid plates are flat projections of the pterygoid processes that serve as attachment sites for chewing muscles and muscles of the throat.

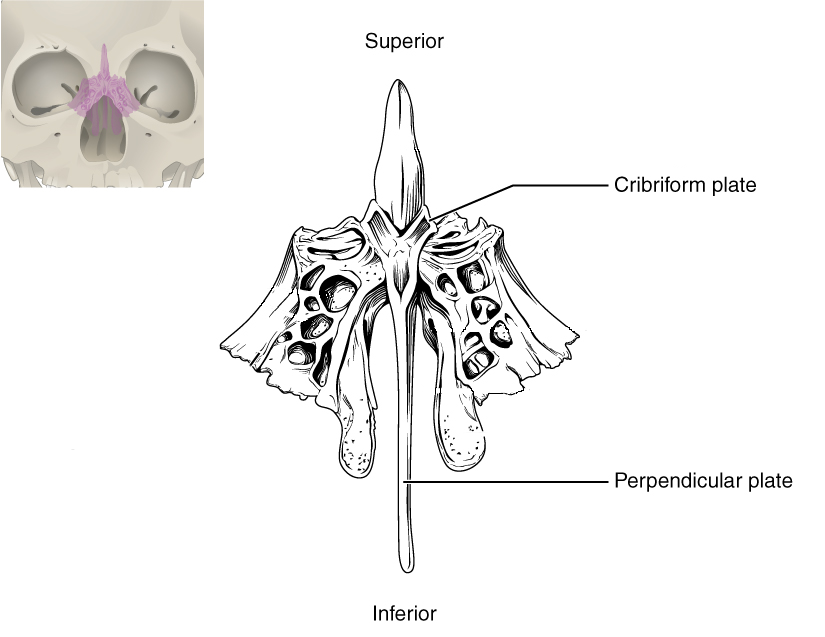

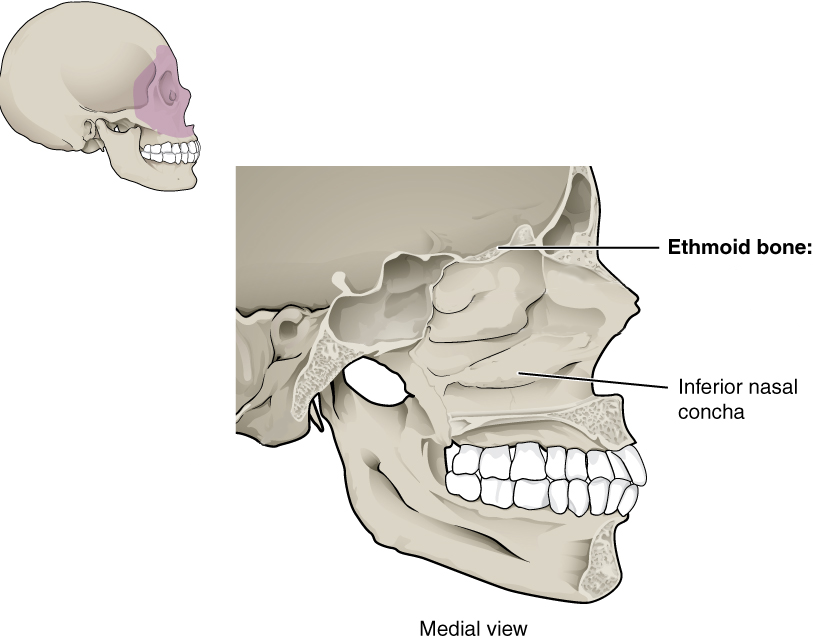

Ethmoid bone: Unpaired bone consisting of a median vertical plate that forms part of the bony nasal septum and a horizontal plate (cribriform plate) with many small cribriform foramina (holes) that transmit olfactory nerves (special sense of smell; Figure A.17).

Bones of the Viscerocranium

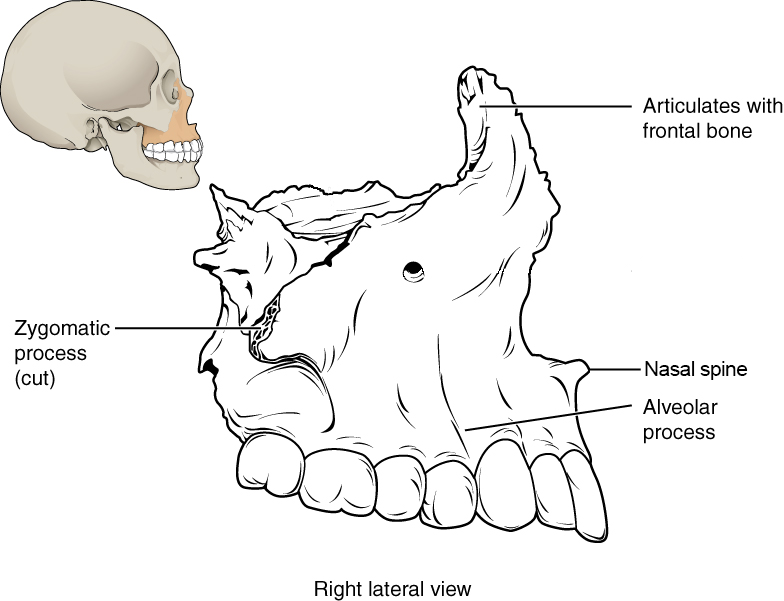

Maxilla bone: Paired bones that form the upper jaw, support the upper teeth, and form the inferior margin of the cheek (Figures A.12, A.15, and A.18).

The nasal spine is a thin projection on the midline at the inferior border of the nasal aperture.

The zygomatic process of the maxilla is the portion of the bone that articulates with the zygomatic bone to form the anterior portion of the zygomatic arch.

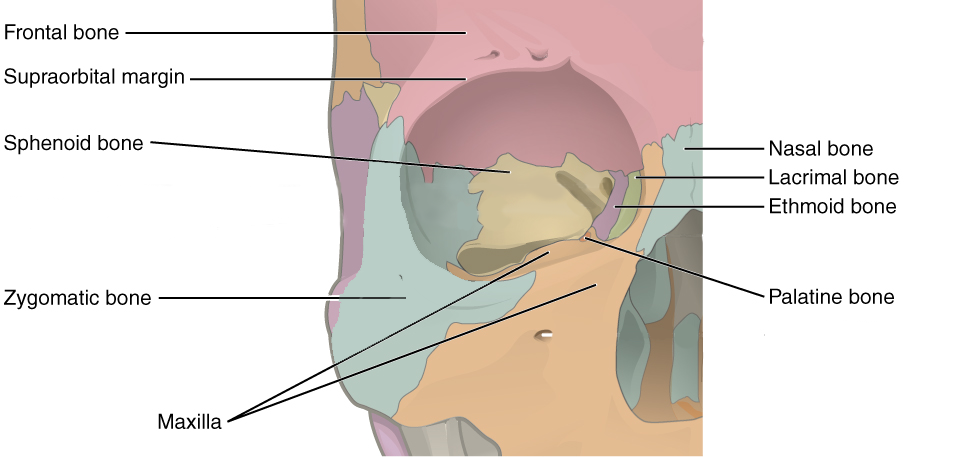

Nasal bone: Small, paired, flat, rectangular bones that form the bridge of the nose (Figure A.19).

Nasal aperture is the anterior opening into the nasal cavity.

Zygomatic bone: Paired bones that form the anterolateral portion of the cheekbone and contribute to the lateral and inferior wall of the orbit (Figure A.19).

The temporal process of the zygomatic bone is the portion of the bone that articulates with the temporal bone to form the anterior portion of the zygomatic arch.

Palatine bone: Paired L-shaped bones that form the posterior portion of the roof of the mouth, floor of the orbit, and the floor and lateral walls of the nasal cavity (Figures A.15 and A.19).

Lacrimal bone: Small, flat, paired bones that form the anterior portion of the medial wall of the orbit (Figure A.19).

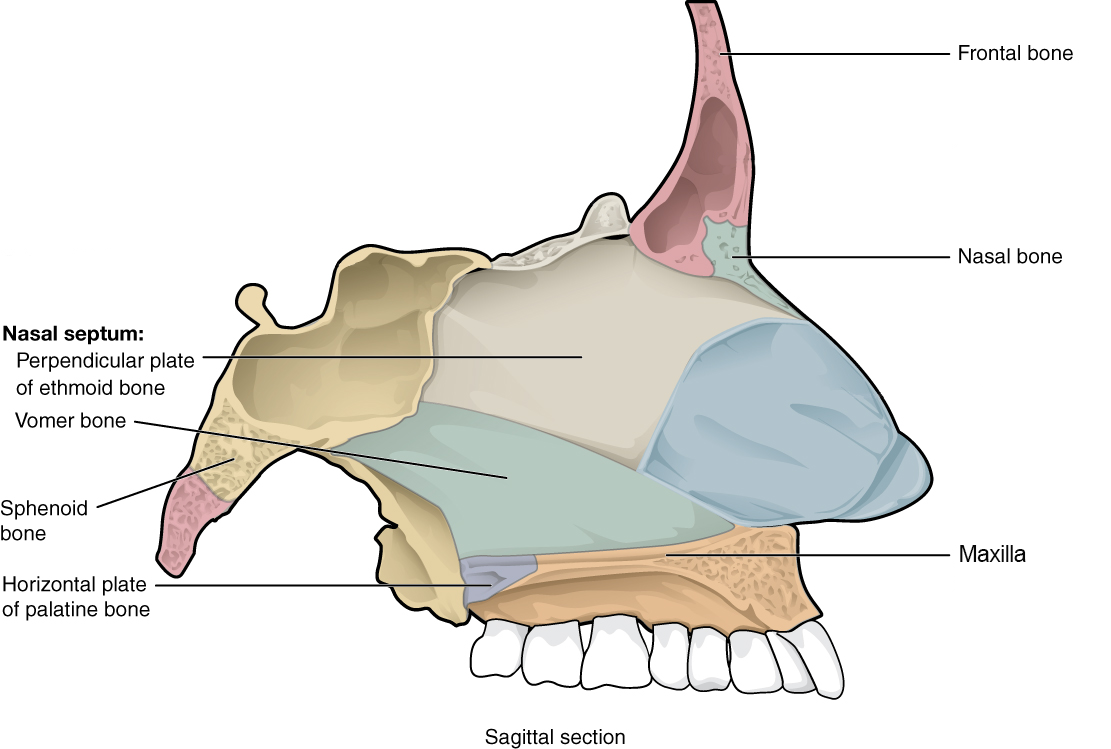

Vomer bone: Unpaired thin bone that forms the inferior portion of the bony nasal septum. It articulates with the ethmoid superiorly (Figure A.20).

Inferior nasal concha bone: Paired bones that project and curl like a scroll from the lateral wall of the nasal cavity (Figure A.21).

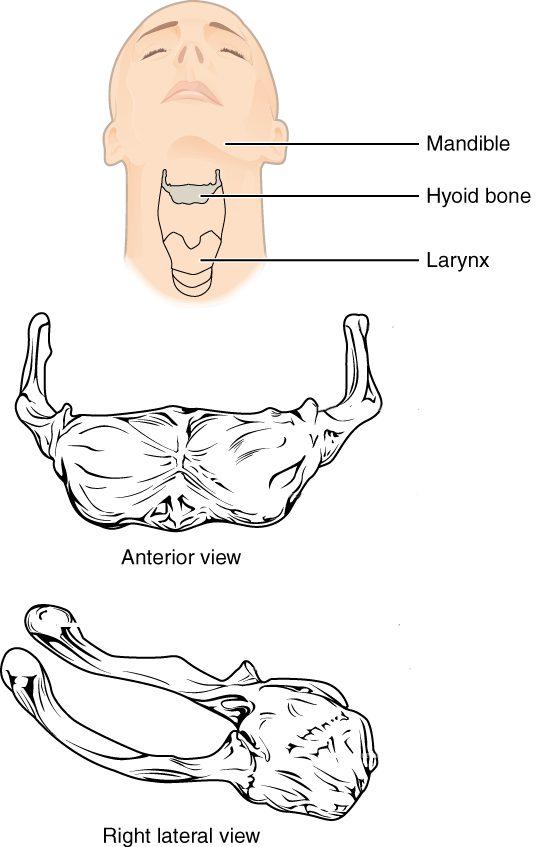

Hyoid bone: Unpaired U-shaped bone that sits in the neck inferior to the mandible. The hyoid is the only bone of the skeleton that does not articulate with another bone. Instead, it is encased in a sling of muscles that move the larynx (voice box), pharynx, and tongue (Figure A.22).

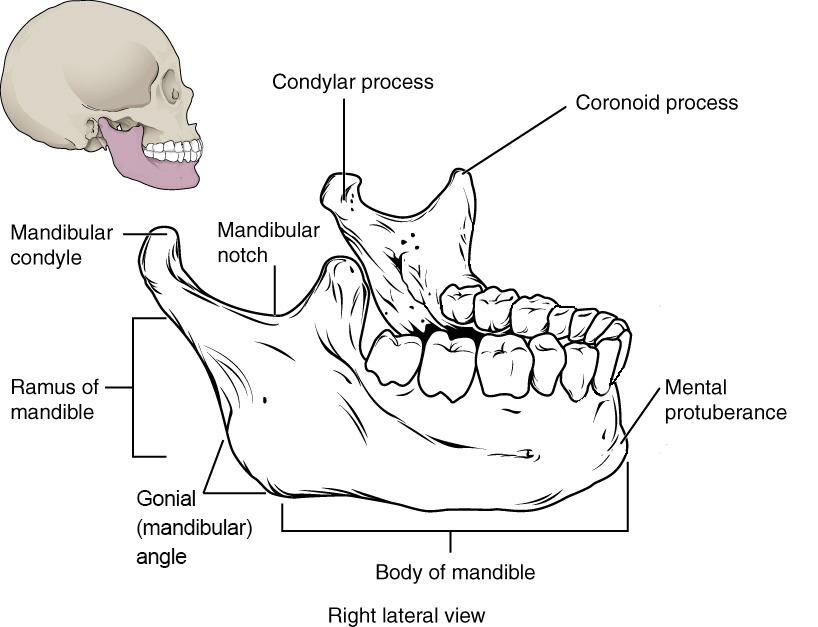

Mandible: Unpaired bone with a horizontal (and anteriorly arched) body and a vertical ramus that articulates with the mandibular fossa to form the temporomandibular (jaw) joint. The body of the mandible houses the lower teeth (Figure A.13 and A.23).

The mental protuberance (eminence) is the most anteriorly projecting point on the mandible—the so-called “chin.” Males tend to have a more prominent mental protuberance than females (Walker 2008).

The ramus of the mandible projects superiorly from the body of the mandible and ascends to one of two features on the superior aspect: coronoid process or mandibular condyle.

The coronoid process is a bony projection off the anterior and superior aspect of the mandibular ramus. The inferior attachment of the temporalis muscle (a chewing muscle) attaches here.

The mandibular condyle, a rounded projection off the posterior and superior aspect of the mandibular ramus. It articulates with the temporal (mandibular) fossa of the temporal bone at the temporomandibular (TMJ) joint.

The gonial (or mandibular) angle is the rounded posteroinferior border of the mandible. It tends to be smooth in females with a more obtuse angle but is laterally flared in males and closer to a right angle in shape (Christensen, Passalacqua, and Bartelink 2019).

Teeth: Adults normally have 32 teeth, distributed among four quadrants of the mouth (upper left, upper right, lower left, lower right). In each quadrant, there are eight teeth: two incisors (central and lateral), one canine, two premolars, and three molars. Each of these types of teeth has a different shape that reflects its function during chewing:

Incisors are flat and shovel shaped and are used to bite into a food item.

Canines are conical, with a single pointed cusp used to puncture a food item.

Premolars have two rounded cusps and are used to grind and mash a food item.

Molars have four (upper molars) or five (lower molars) flatter cusps and are used to grind food prior to swallowing.

The teeth have their own set of directional terms that help differentiate the different parts of the tooth. For example, the anterior portion of the tooth is called mesial, while the posterior portion of the tooth is called distal. In the case of teeth in the front of the mouth, mesial refers to the aspect toward the midline of the body; distal refers to the aspect away from the midline. Similarly, the side of the tooth facing the lips is called the buccal surface and the side facing the tongue is called the lingual surface. Finally, we can talk about the occlusal surface of the tooth, which is the surface that comes in contact with food or the teeth from the other jaw when the jaw is closed. Sometimes the occlusal surface of the incisors is called the incisal surface.

Vertebral Column

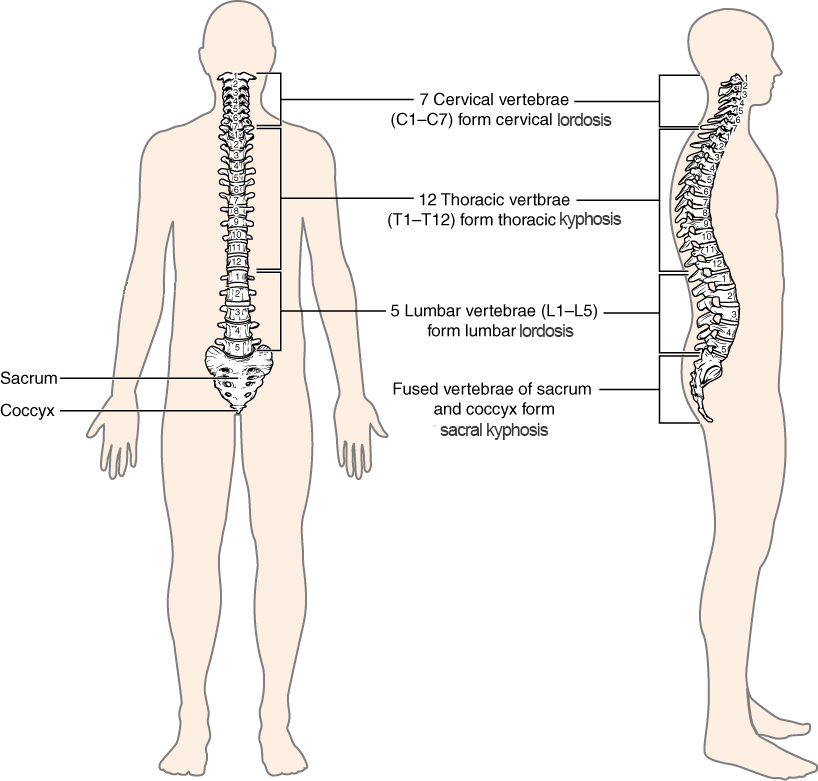

The adult vertebral column consists of 32–33 individual vertebrae, divided into five regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal.

General Structure of a Vertebra

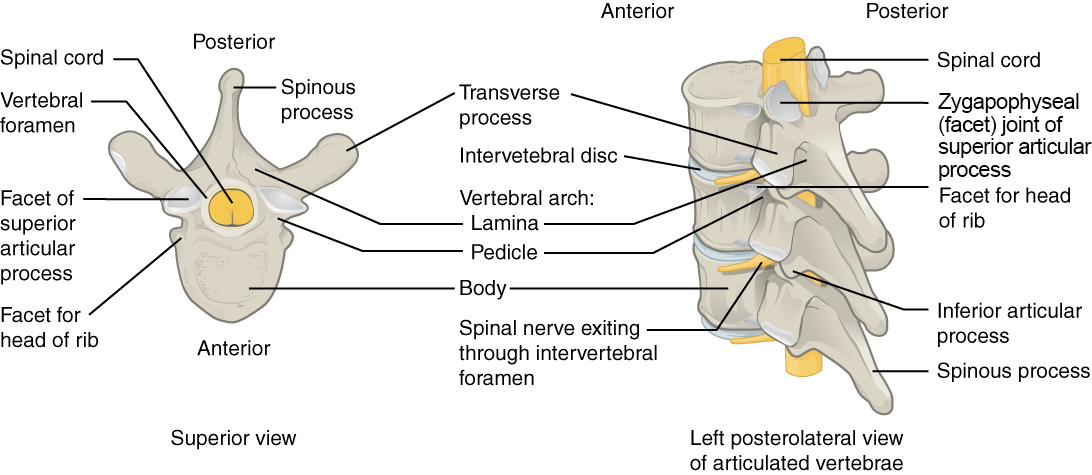

A typical vertebra consists of an anteriorly situated centrum (body)—the main weight-bearing element of the vertebra—and a posteriorly projecting vertebral arch (Figure A.24). The vertebral arch consists of the paired pedicles and paired laminae. The pedicle connects the transverse process—a laterally projecting process that serves as an attachment site for muscles and ligaments—to the vertebral body; the lamina connects the spinous process—a posteriorly projecting process that serves as an attachment site for muscles and ligaments—to the transverse process. Projecting inferiorly off the vertebral arch is the inferior articular process, and projecting superiorly off the vertebral arch is the superior articular process. Between the vertebral body anteriorly and the vertebral arch posteriorly is an open space called the vertebral foramen.

Vertebrae articulate with one another through two major types of joints: intervertebral disc joints between adjacent vertebral bodies and zygapophyseal (facet) joints between the inferior articular process of one vertebra and the superior articular process of the vertebra immediately inferior to it. When all vertebrae are articulated into a column, the adjacent vertebral foramina form the vertebral canal, through which the spinal cord travels from the foramen magnum of the occipital bone to approximately the level of the second lumbar vertebra. At the level of each vertebra, the spinal cord gives off a pair (left and right) of spinal nerves that exit between vertebrae through the intervertebral foramen formed by adjacent vertebral arches. Even though the spinal cord ends in the lumbar region, the spinal nerves emanating from the spinal cord continue all the way to the sacral (and sometimes coccygeal) region, culminating in a total of 30–31 pairs of spinal nerves.

Regional Differences in Vertebral Shape

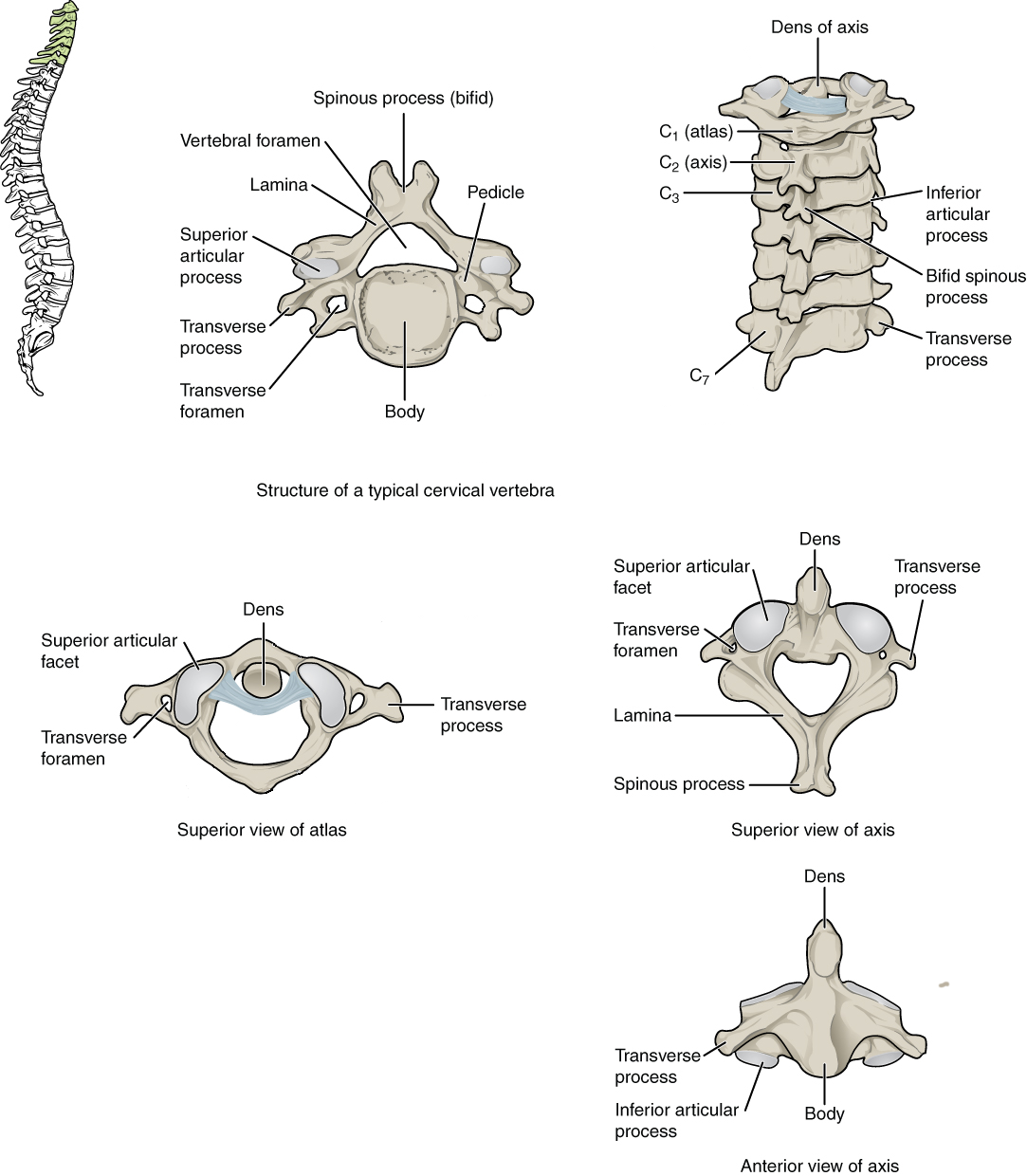

In the cervical region of the vertebral column, there are seven vertebrae (named C1–C7 from superior to inferior; Figure A.25). The first two cervical vertebrae are unique from each other and all other cervical vertebrae, and they get special names: atlas (C1) and axis (C2). The atlas lacks a vertebral body (having only two large articular facets for articulation with the occipital bone of the skull: the atlanto-occipital joint for nodding the head) and does not have a spinous process. The axis is notable for the superiorly projecting dens(or odontoid process), which articulates with the atlas to create the atlanto-axial joint for head rotation. Otherwise, a typical cervical vertebra has a small vertebral body, a bifid (split) spinous process, a transverse process with a transverse foramen on it for passage of the vertebral artery and vein, and a triangular-shaped vertebral foramen.

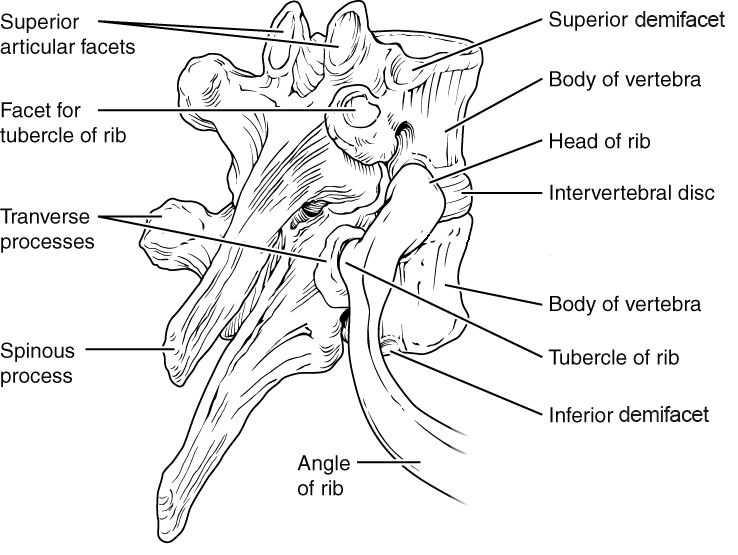

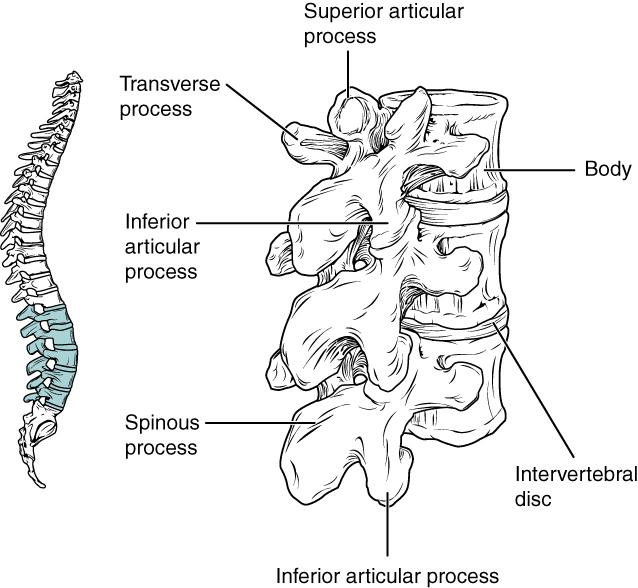

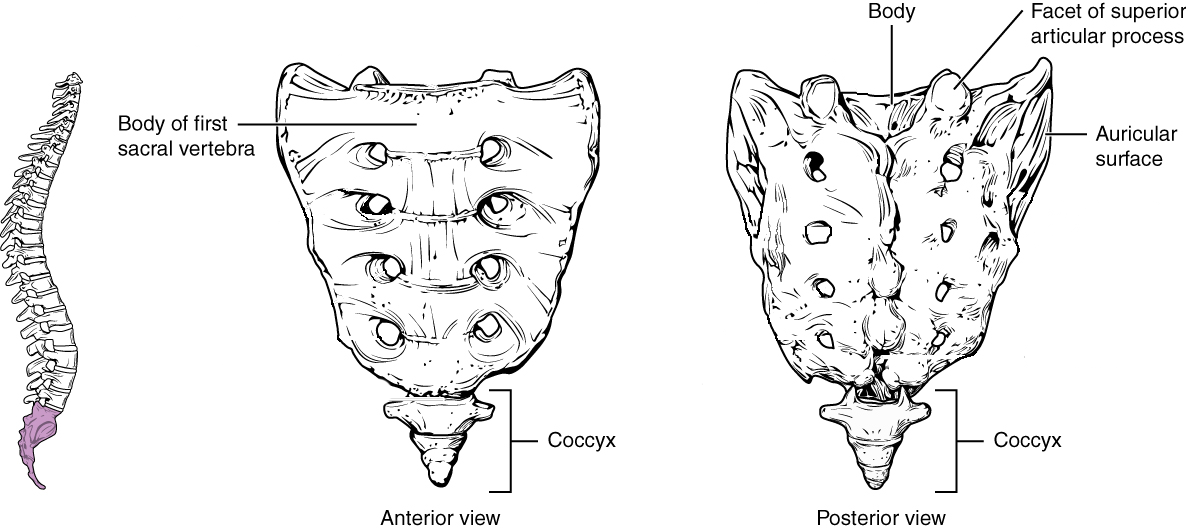

The vertebrae in the other regions of the spinal column are less variable in shape than the cervical region vertebrae. There are 12 thoracic region vertebrae (T1–T12), and they can be easily distinguished from the vertebrae in other regions because they have articular facets on their vertebral bodies for articulation with the head of a rib, as well as articular facets on the transverse process for articulation with the rib tubercle (Figure A.26). In particular, the vertebral bodies of T2–T9 have two pairs of articular facets called demifacets (superior and inferior), for articulation with multiple ribs; T1 and T10–T12 have single facets for articulation with a single rib. All five lumbar region vertebrae (L1–L5) are distinguished by their large vertebral body and rounded spinous process (Figure A.27). Finally, there is the sacrum, which is a bone of the pelvis that forms from the fusion of all five sacral region vertebrae (S1–S5), and there is the coccyx, which comprises three to four fused coccygeal region vertebrae that form the tailbone (Figure A.28).

Curvatures of the Vertebral Column

The adult spine is curved in the midsagittal plane in four regions of the vertebral column (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral; Figure A.29). During the fetal period of development, the vertebral column forms an anteriorly concave curvature called a kyphosis. But during the postnatal period, when an infant learns to hold its head up and then again when it learns to walk, it develops secondary curvatures called lordoses (singular: lordosis) that are posteriorly concave in the cervical and lumbar vertebral regions, while the kyphoses remain in the thoracic and sacral regions. The end result is an S-shaped curvature to our spine that enables us to keep our head and torso above our center of mass (near our pelvis) while walking around on two legs.

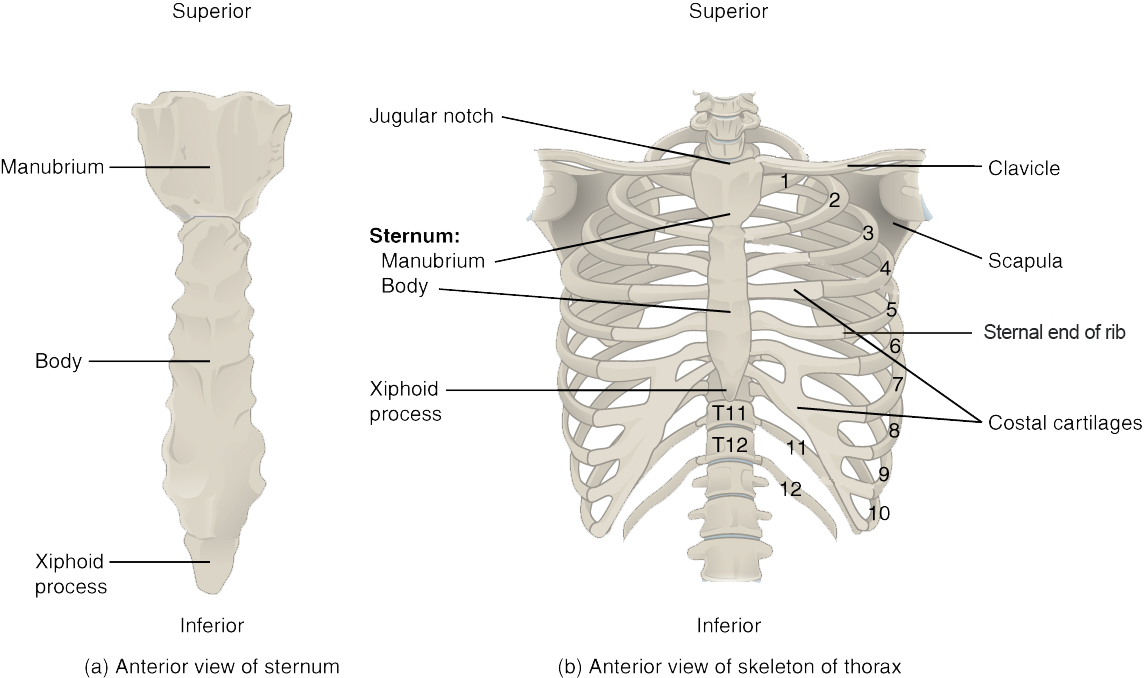

Thoracic Cage

The thoracic cage is formed from the sternum, the 12 ribs and their cartilages (costal cartilages), and the 12 thoracic vertebrae with which the ribs articulate (Figure A.30). The sternum comprises the manubrium (superior portion), the body of the sternum, and the xiphoid process

. Each rib has a head and neck (with rib tubercle) at the vertebral end of the rib as well as a flattened shaft that extends to articulate with the sternum. All ribs articulate with the vertebral column at two points: the transverse process facet (rib tubercle) and vertebral body articular facet (head of rib). But articulations between the ribs and the sternum vary, where some ribs (1–7, the “true ribs”) attach directly to the sternum via their costal cartilages, other ribs (8–10, the “false ribs”) attach indirectly to the sternum via the costal cartilage of the rib above, and some ribs (11–12, the “floating ribs”) do not attach to the sternum at all. With increasing age, the sternal end of the rib becomes thinner and irregularly shaped compared to the smooth, rounded shape seen in young adults (Hartnett 2010).

Appendicular Skeleton

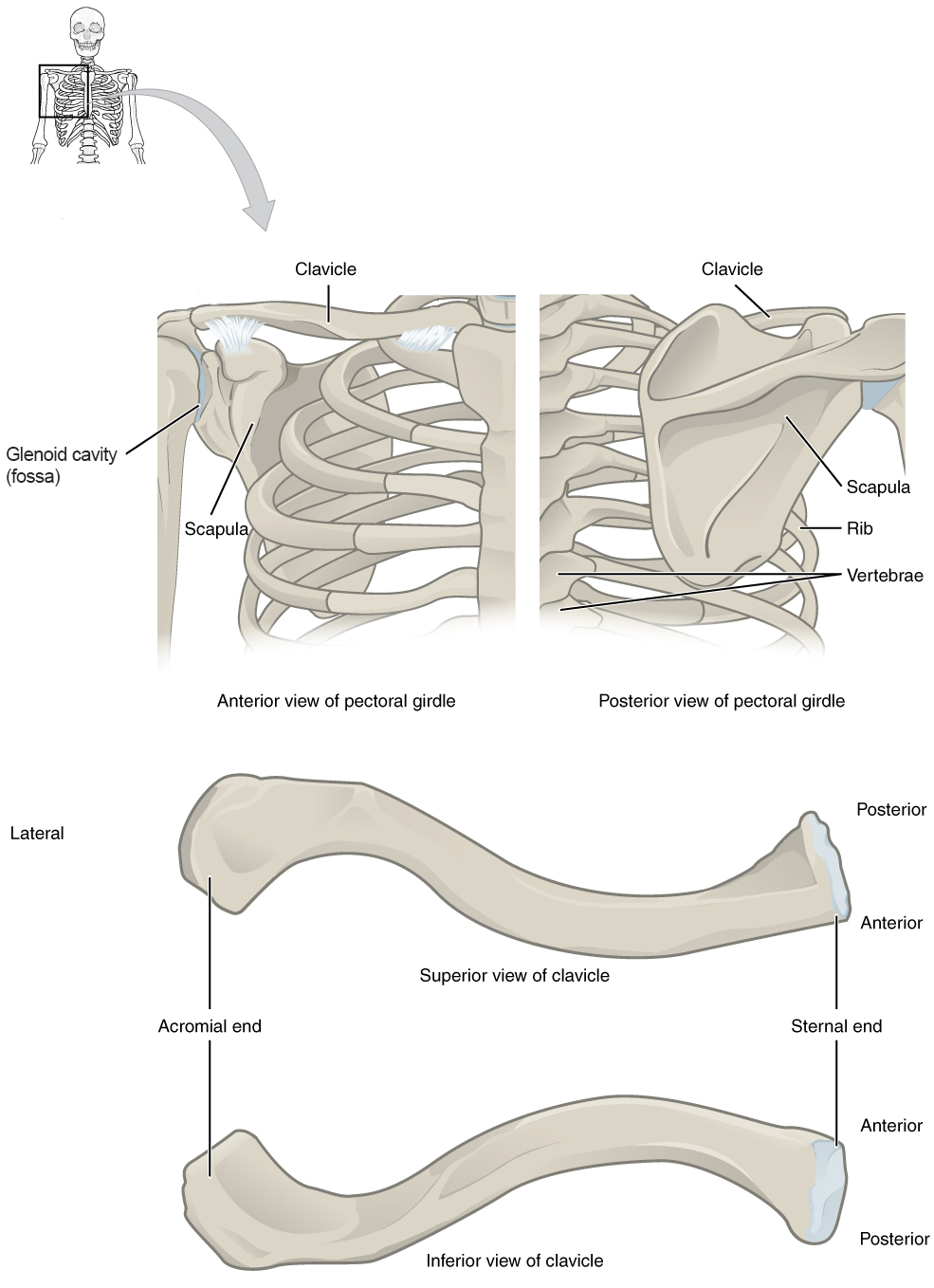

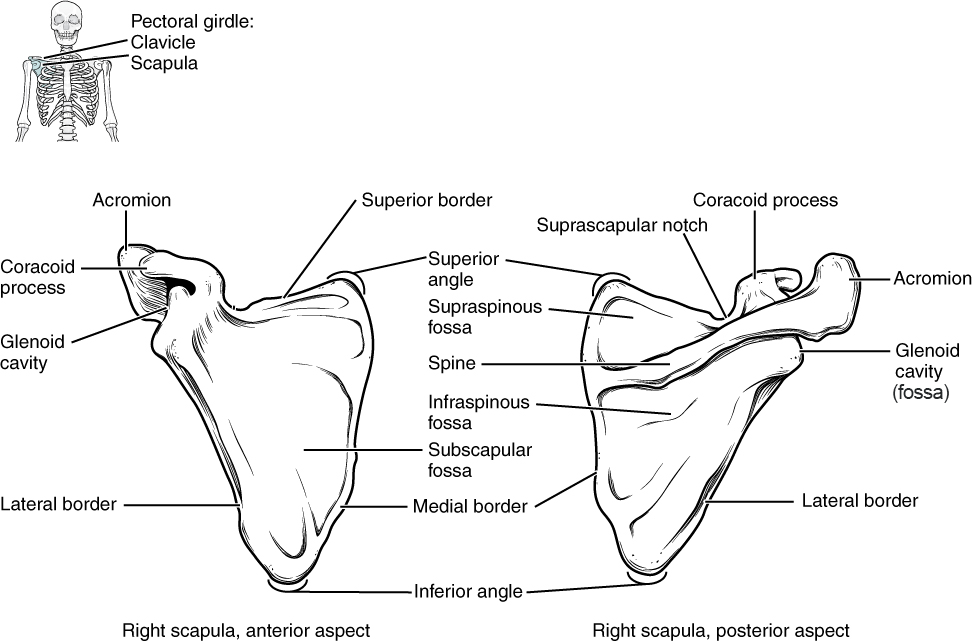

Pectoral Girdle

The pectoral girdle consists of the clavicle and the scapula, and it serves as the proximal base of the upper limb as well as the anchor for the upper limb to the axial skeleton. The clavicle is an S-shaped bone, and it forms the strut that connects the scapula to the sternum (Figure A.31). The scapula is a large, flat bone with three angles (superior, inferior, and lateral) and three borders (medial, lateral, and superior). The lateral angle is noteworthy because it serves as the articulation for the head of the humerus of the upper limb at the glenoid cavity (or fossa) (Figure A.32). The borders and the anterior and posterior surfaces of the scapula are sites of muscle attachment. The scapula also has three important projections for muscle and ligament attachments: the coracoid process anteriorly and superiorly; the acromion, which articulates with the lateral end of the clavicle; and the spine on the posterior aspect of the scapula.

Upper Limb

The bones of the upper limb skeleton include the humerus, radius, ulna, eight carpal (wrist) bones, five metacarpal (hand) bones, and 14 phalanges (finger bones). Each of these bones is described below along with several of the prominent features.

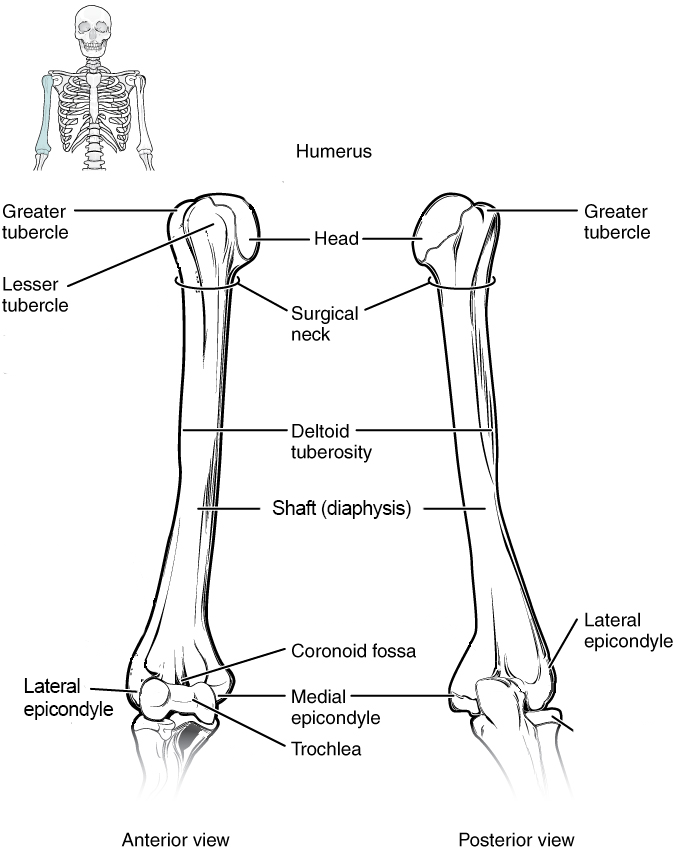

The humerus is the bone of the arm. On the proximal epiphysis of the humerus are attachment sites for muscles of the rotator cuff (greater tubercle and lesser tubercle). A major shoulder muscle (deltoid muscle) attaches to the humerus along the lateral aspect of the diaphysis at the deltoid tuberosity. On the distal epiphysis of the humerus, the medial epicondyle is an attachment site for muscles that flex the forearm, and the lateral epicondyle is an attachment site for muscles that extend the forearm (Figure A.33).

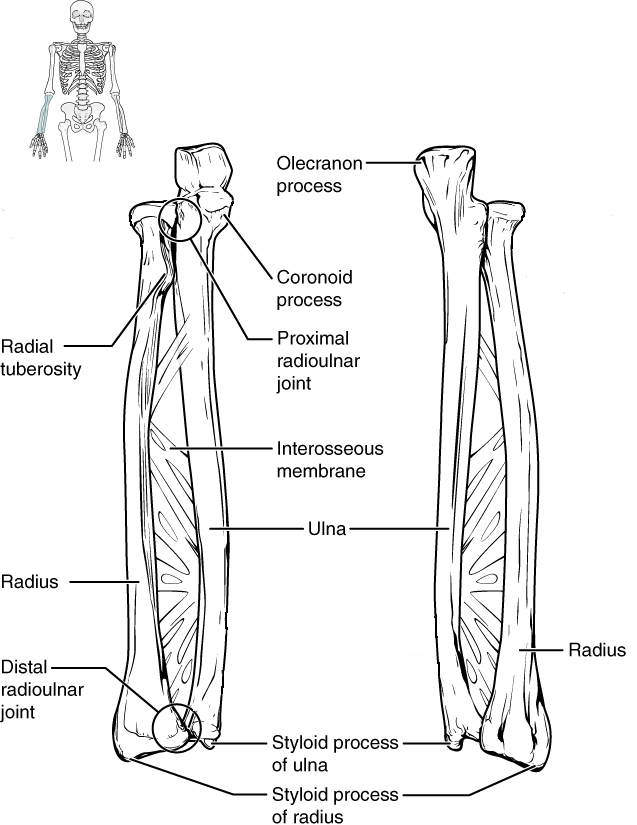

There are two bones of the forearm, attached to each other by a thick connective tissue interosseous membrane: the radius and the ulna (Figure A.34). The radius is lateral to the ulna in anatomical position (this is called supination of the forearm), but it crosses over the ulna when the wrist is rotated so that the thumb points medially (this is called pronation of the forearm). On the proximal end of the radius is the radial tuberosity, an attachment site for the biceps brachii muscle that will help supinate and flex the forearm; on the distal end of the radius is the styloid process of radius, an attachment site for ligaments of the wrist. The ulna also has a styloid process (styloid process of ulna), but unlike the one on the radius it does not have a relevant function. Instead, the important processes on the ulna are located proximally, and they include the olecranon process for the attachment of the triceps brachii muscle (a muscle that extends the forearm and arm) and the coronoid process for the attachment of the brachialis muscle (a muscle that flexes the forearm).

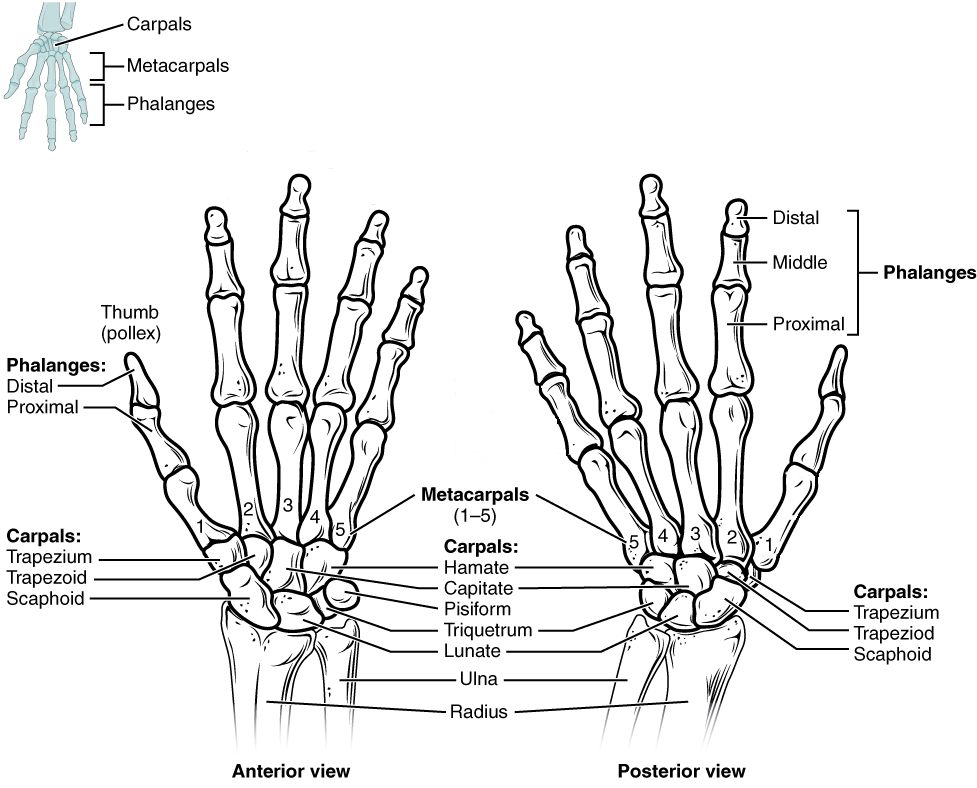

There are eight carpal bones that comprise the wrist, and they are organized into two rows: proximal and distal (Figure A.35). The proximal row of carpals (from lateral to medial) includes the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform. The distal row (from lateral to medial) includes the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate with its distinctive hamulus (hook) for muscle and ligament attachments. Distal to the carpal bones are the digital rays, each of which contains a metacarpal (hand) bone and three phalanges (proximal, middle, and distal) or finger bones. The exception to this rule is the thumb, which has fewer phalanges (proximal and distal, but no middle) than the other digits.

Pelvic Girdle

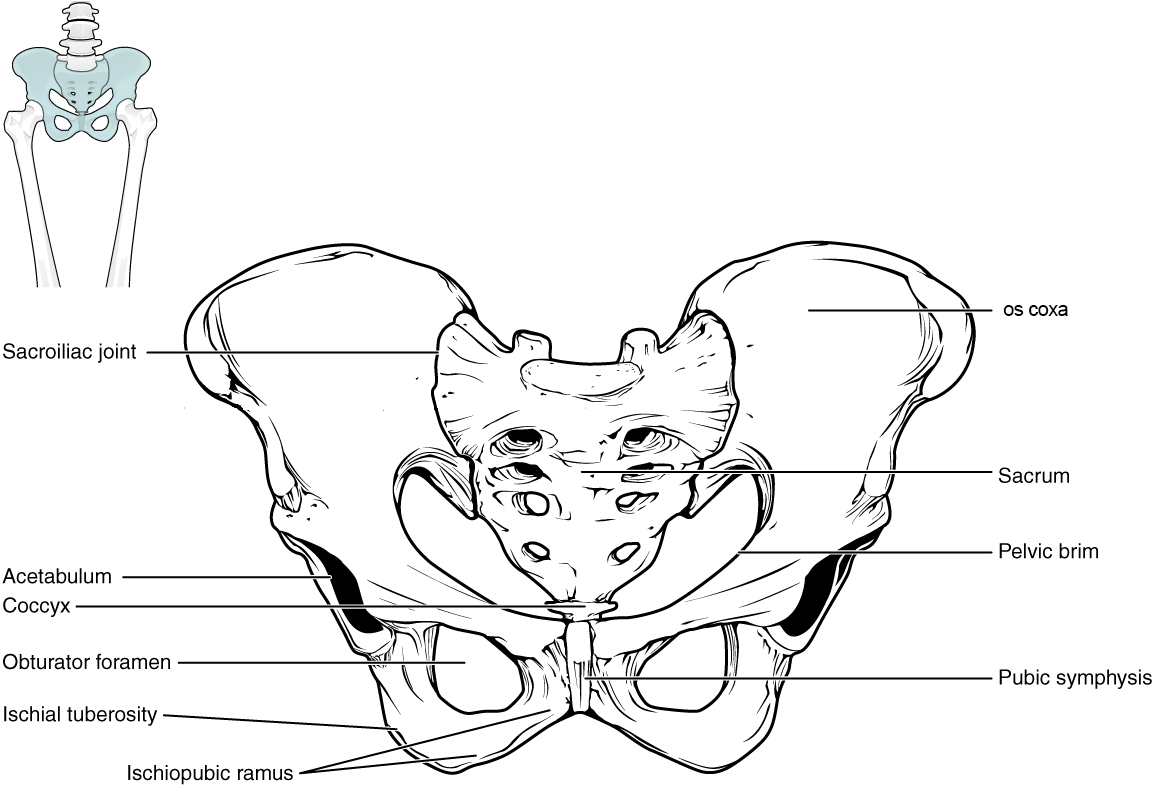

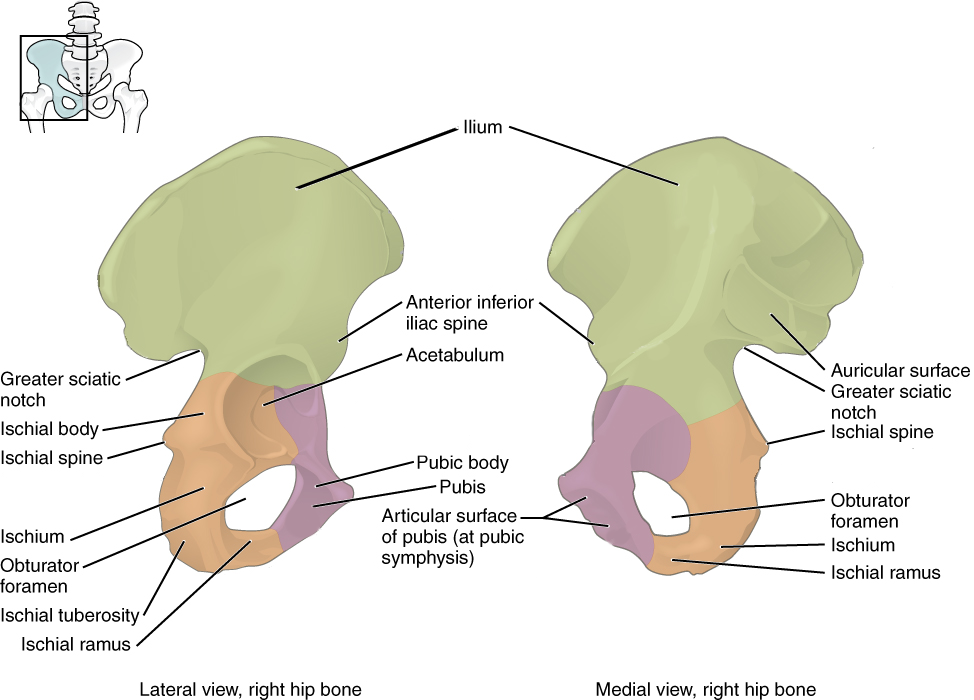

The pelvic girdle consists of the two os coxae and the sacrum that articulates with both, and it serves as the proximal base and anchor of the lower limb to the axial skeleton. Each os coxa comprises three bones that fuse together during growth: ilium, ischium, and pubis. These three bones fuse in a region called the acetabulum, which is the socket for the ball-and-socket hip joint (Figure A.36). The ilium, the flared superior portion of the pelvis, is the largest bone of the os coxa and serves as a major site of attachments for muscles from the abdomen, back, and lower limb. The ilium has several important features including the auricular surface, the surface where the ilium articulates with the sacrum. The auricular surface is used to estimate age at death as the surface progressively deteriorates with increasing age to appear coarse and porous. The greater sciatic notch is a large notch in the ilium that allows for several structures to leave the pelvis and enter the lower extremity, including the sciatic nerve. In females, the notch tends to be symmetrical whereas in males it tends to curve posteriorly (Nawrocki et al. 2018).

The ischium forms the posterior and inferior portion of the os coxa. There are two significant projections of note on the ischium: the ischial spine and tuberosity. The ischial spine is the attachment point for a major pelvic ligament and is located inferior to the greater sciatic notch of the ilium. The ischial tuberosity is the proximal attachment site for the hamstring muscles of the lower limb.

The anterior and medial portions of the os coxa are formed by the pubis. The pubis is a useful bone with which to sex a skeleton in a forensic context (Bass 2005; Buikstra and Ubelaker 1994). The body of pubis is the superior and medial portion (Figure A.37). The body tends to be rectangular in cross-section in females and triangular in males. The bony projection that unites the ischium and pubis anteriorly is called the ischiopubic ramus. Females tend to display a thin and sharp ramus on the medial surface while the surface in males tends to be broad and blunt. The joint that unites the two pubic bones in the front of the pelvis is called the pubic symphysis, which is a structure commonly used in age estimation. In young adults, the surface is billowed, but it transitions to being smooth and porous with increasing age (Hartnett 2010). The subpubic concavity is a depression inferior to the ischiopubic ramus. Female pelves tend to exhibit this concavity while male pelves tend not to. Finally, the large opening encircled by the pubis and ischium is called the obturator foramen. The shape of the foramen in females has been described as triangular while it is more likely to appear oval in males (Bass 2005).

Lower Limb

The bones of the lower limb skeleton include the femur, patella, tibia, fibula, seven tarsal (ankle) bones, five metatarsal (foot) bones, and 14 phalanges (toe bones). Each of these bones is described below along with several of the prominent features.

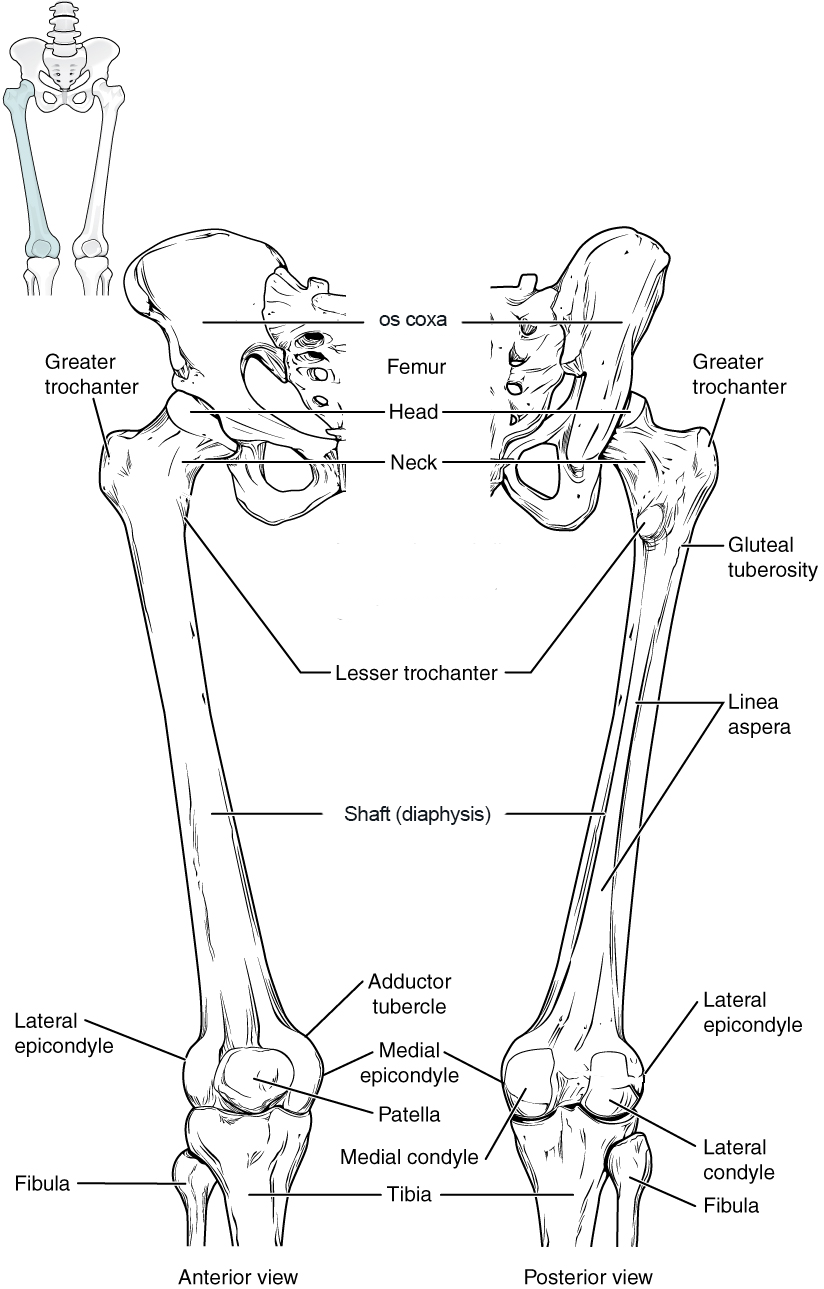

The femur is the bone of the thigh. On the proximal epiphysis of the femur are attachment sites for major hip and thigh muscles on the greater trochanter, lesser trochanter, and gluteal tuberosity (Figure A.38). The raised ridge on the posterior aspect of the femoral diaphysis is called the linea aspera, and it is a major attachment site for the quadriceps femoris muscles and other muscles, and it terminates distally by splitting into medial and lateral epicondyles, additional sites of muscle attachment. The distal epiphysis of the femur is marked by two rounded condyles that articulate with the proximal part of the tibia. The anterior surface of the distal femur articulates with the patella (kneecap), a bone that develops within the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle to enhance the function of the muscle. The patella does not articulate with the tibia.

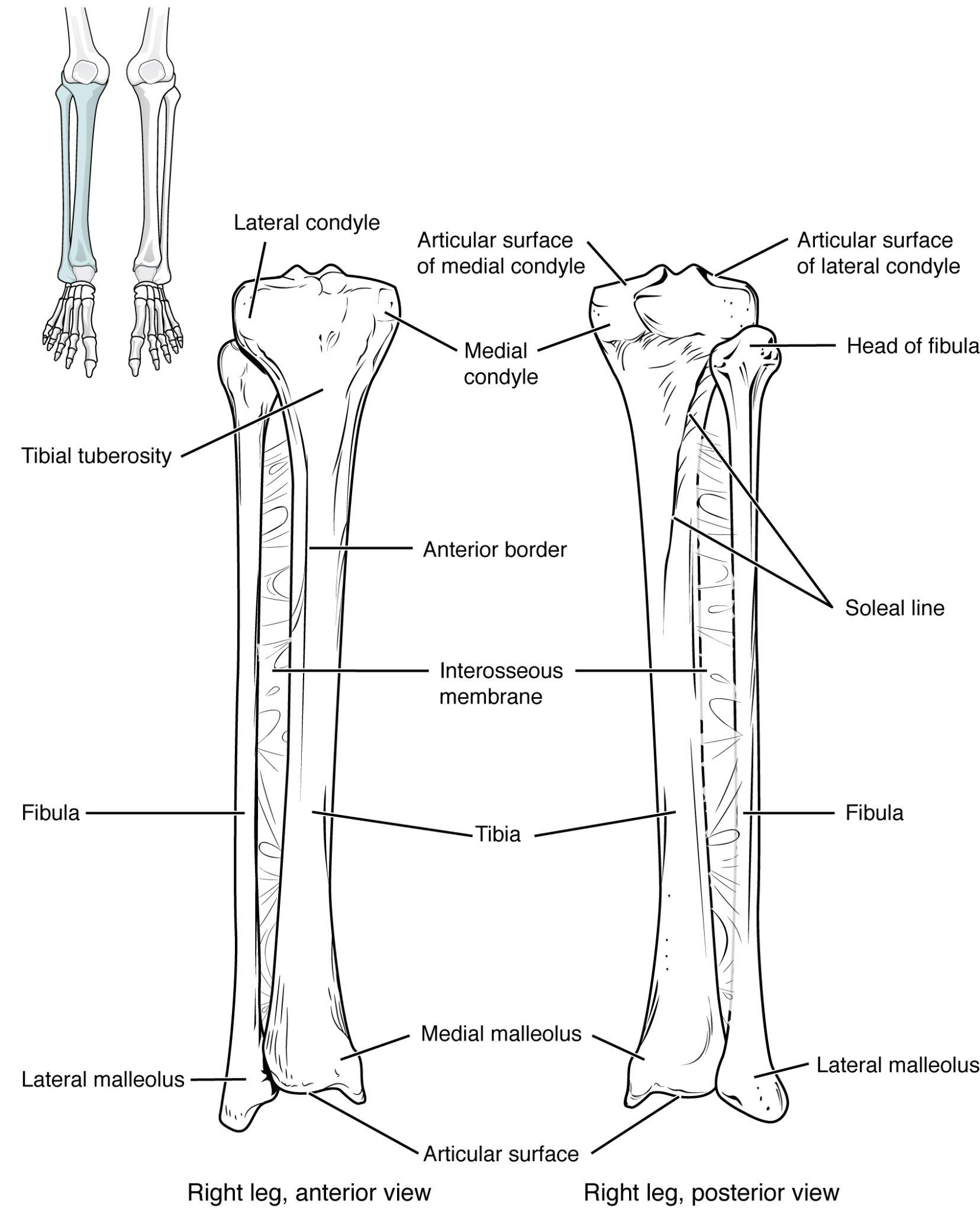

There are two bones of the leg: tibia and fibula. The tibia is the robust, medial bone of the leg, and it is connected to the laterally positioned fibula by an interosseous membrane like in the forearm (Figure A.39). The proximal epiphysis of the tibia has two articular facets called tibial condyles that articulate with the femoral condyles. On the anterior surface of the proximal tibia is a raised projection called the tibial tuberosity, where the quadriceps muscle tendon attaches distally after containing the patella. On the distal epiphysis of the tibia is the medial malleolus, which articulates with the talus in the ankle joint. The lateral malleolus is a feature of the distal end of the fibula; the proximal end of the fibula articulates with the lateral portion of the proximal tibia.

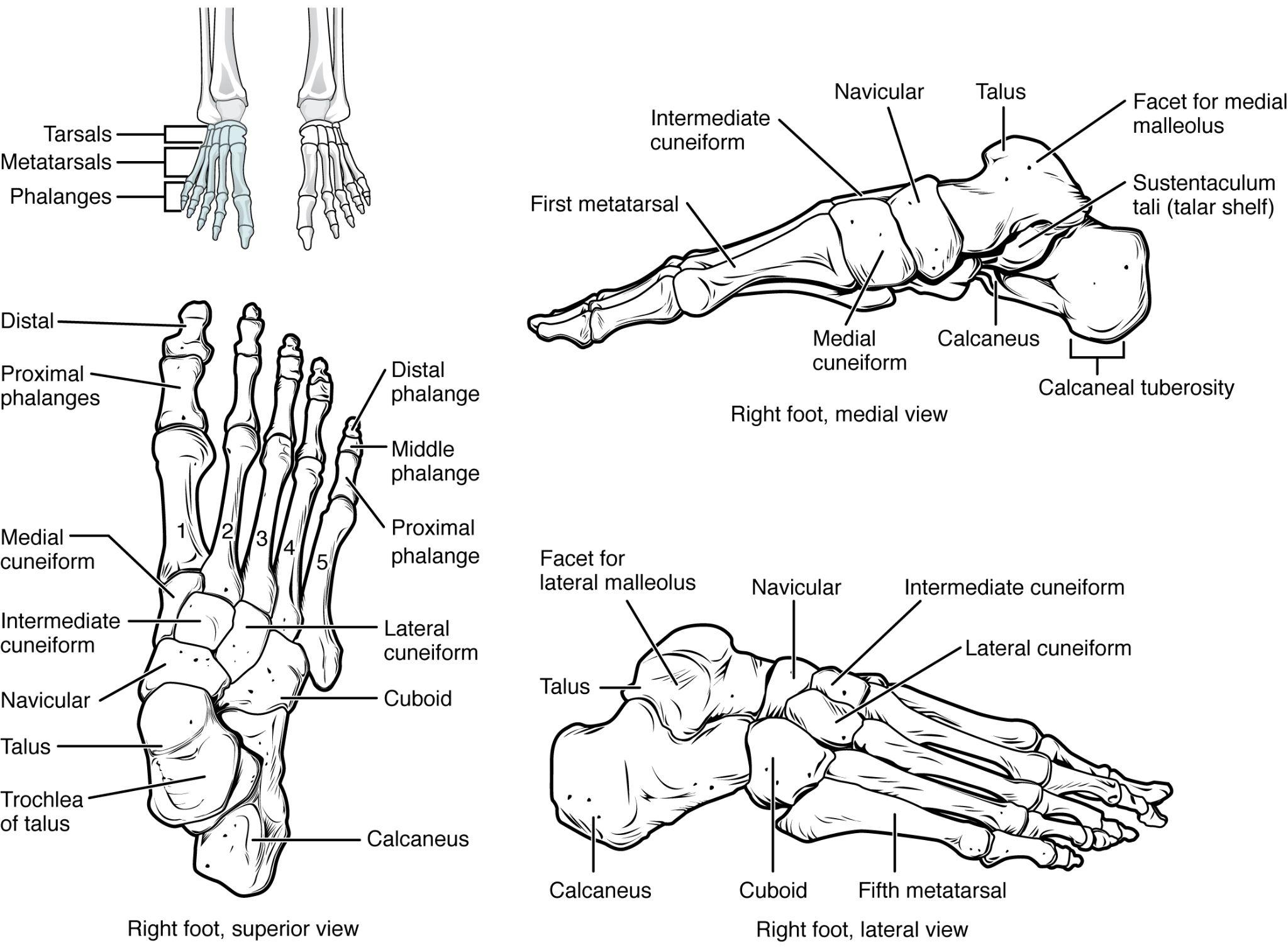

There are seven tarsal bones that comprise the ankle (Figure A.40). The talus is the most superior of the tarsals, and it articulates with the distal tibia and distal fibula superiorly and with the calcaneus inferiorly. The calcaneus is the heel of the foot; it is the largest of the tarsals. On the posterior-most aspect of the calcaneus is the calcaneal tuberosity, which is the attachment site for the Achilles tendon of the posterior leg. Distal to the talus is the medially positioned navicular, the three cuneiform bones (medial, intermediate, and lateral), and the laterally positioned cuboid. Distal to the tarsals are the digital rays, each of which contains a metatarsal (foot) bone and three phalanges (proximal, middle, and distal) or toe bones. The exception to this rule is the big toe, which has fewer phalanges (proximal and distal, but no middle) than the other digits.

Review Questions

- Which bony features of the pelvic girdle are relevant to estimating age and/or sex in forensic and bioarchaeological contexts? Give specific examples of how these features differ among sexes.

- What is the mechanistic difference between endochondral and intramembranous bone formation?

- Which bones articulate with the calcaneus? Which bones articulate with the humerus?

- Which elements of the skeleton belong to the axial skeleton versus the appendicular skeleton?

Key Terms

Acetabulum: Shallow cavity of the coxa for articulation of the head of the femur.

Acromion: Lateral projection of the spine of scapula.

Anatomical position: Standing upright, facing forward with arms at the side and palms facing forward.

Anterior (ventral): Toward the front.

Appendicular skeleton: Part of the skeleton that consists of the bones of the pectoral and pelvic girdls, arms, and legs.

Atlanto-axial joint: Joint between the atlas (C1 vertebrae) and the axis (C2 vertebrae), used for turning the head side to side.

Atlanto-occipital joint: Joint between the atlas (C1 vertebrae) and occipital bone, used for nodding the head.

Auricular surface: Roughened joint surface for articulation of the sacrum.

Axial skeleton: Part of the skeleton that consists of the bones of the head and trunk.

Body of pubis: Superior bar of the pubis.

Body of the sternum: Central portion of the sternum where ribs articulate.

Buccal: Toward the cheek.

Calcaneal tuberosity: Roughened attachment site at the posterior calcaneus.

Calcaneus: Large bone that forms the heel.

Cancellous (or trabecular) bone: Porous bone found at the ends of long bones and within flat and irregular bones.

Canines: Conical teeth with a single pointed cusp used to puncture a food item.

Carpal bones: The 8 bones of the wrist: scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform, trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate.

Centrum: Anterior body of vertebra; the main weight-bearing element of the vertebra.

Cervical region: Neck region that contains 7 vertebrae.

Clavicle: The collarbone, which connects the sternum to the scapula to form the pectoral girdle.

Coccyx: Small triangular bone that projects from the inferior part of sacrum.

Coracoid process: Hook-shaped projection from the anterior surface of the scapula.

Coronal (frontal) plane: An imaginary line that divides the body into anterior and posterior halves.

Coronal suture: Joint that connects the frontal bone to the paired parietal bones.

Coronoid process: Triangular eminence from the superior part of the mandibular ramus.

Coronoid process of ulna: Triangular projection from the anterior surface of proximal ulna.

Cortical (or compact) bone: Dense, outer surface of bone.

Cranial sutures: Fibrous joints that connect bones of the skull and face.

Cranium: Bones of the head that support the brain and face.

Cribriform foramina: Small openings in the superior plate of the ethmoid that transmit olfactory nerves.

Deltoid tuberosity: Lateral projection for attachment of deltoid muscle.

Demifacets: Partial joint surfaces on the lateral surface of the centrum of thoracic vertebrae.

Dens (or odontoid process): Projection from superior surface of centrum of C2.

Diaphysis: Shaft or central part of a long bone.

Distal: Further away from the center of the body or point of attachment.

Endochondral bone formation: Process of bone formation that occurs from a cartilage model.

Epiphysis: End of long bones.

Ethmoid bone: Unpaired bone of the skull that separates the nasal cavity from the brain.

External occipital protuberance (EOP): Projection from the occipital superior to nuchal lines.

Femur: Long bone of the thigh.

Fibula: Lateral bone of the leg.

Flat bone: Bones that are flat with thin layers of cortical bone surrounding cancellous bone.

Foramen magnum: Large opening in the occipital where the spinal cord passes.

Frontal bone: An unpaired bone that forms the anterior and superior part of the cranium.

Glabella: Part of the forehead between the eyebrows.

Glenoid cavity (or fossa): Shallow depression for the articulation of the head of the humerus.

Gluteal tuberosity: Roughened attachment site for the gluteus maximus muscle.

Gonial (or mandibular) angle: Posterior border of the mandible at the junction of the ramus and body.

Greater sciatic notch: Large indentation of the ilium.

Greater trochanter: Large projection from the lateral surface of the proximal femur.

Greater tubercle: Large projection on the superior and lateral surface of the humerus.

Head of rib: Posterior part of the rib that articulates with the centrum.

Humerus: Long bone of the arm.

Hyoid bone: U-shaped bone in the neck that does not articulate with another bone.

Ilium: Large flat bone of the superior part of the coxa.

Incisal surface: Toward the cutting edge.

Incisors: Flat and shovel shaped teeth that are used to bite into a food item.

Inferior (caudal): Away from the head or downward.

Inferior articular process: Inferior projections from the vertebral arch that connect to superior articular processes of the inferior vertebra.

Inferior nasal concha: Scroll-like paired bones that attach to the lateral part of the nasal cavity.

Intervertebral disc joints: Fibrocartilaginous joints that connect adjacent centra of vertebrae.

Intramembranous bone formation: Process of bone formation that occurs in mesenchyme and gives rise to flat bones of the skull.

Irregular bone: Bones that have a complex appearance.

Ischial spine: Thin, square projection from the ischium.

Ischial tuberosity: Large, round protrusion of the posterior and inferior ischium.

Ischiopubic ramus: Thin bar of bone that unites the pubis and ischium.

Ischium: The posterior and inferior portion of the os coxae.

Kyphosis: Anterior curvature of the spine.

Lacrimal bone: Paired bones that form the anterior and medial part of the orbit.

Lambdoidal suture: Joint that connects the parietal and occipital bones.

Lamina: Flattened portion of the vertebral arch.

Lateral: Further away from the midline.

Lateral malleolus: Prominence of the distal fibula that forms the outer part of the ankle.

Lesser trochanter: Projection from the medial surface of the proximal femur.

Lesser tubercle: Projection on the anterior and superior surface of the humerus.

Linea aspera: Elongated projection of the posterior surface of the femur.

Lingual: Toward the tongue.

Long bone: Bones that are longer than they are wide.

Lordosis: Posterior curvature of the spine.

Lumbar region: Lower back region that consists of 5 vertebrae.

Mandible: Lower jaw bone.

Mandibular condyle: Rounded projection of the mandibular ramus.

Mandibular fossa: Depression at the base of the temporal bone where the mandibular condyle articulates to form the temporomandibular (or jaw) joint.

Manubrium: Upper part of the sternum.

Mastoid process: Bony projection from the back of the temporal bone.

Maxilla bone: Upper jaw bone.

Medial: Toward the midline.

Medial malleolus: Prominence of the distal tibia that forms the inner part of the ankle.

Medullary cavity: Central cavity in the diaphysis of long bones that contains bone marrow.

Mental protuberance (eminence): Triangular projection at the front of the mandible.

Mesial: Toward the middle.

Metacarpal: The 5 bones of the palm of the hand.

Metaphysis: Junction between diaphysis and epiphysis where bone growth occurs.

Metatarsal: The 5 bones at the distal part of the foot.

Metopic suture: Joint that connects paired frontal bones and usually fuses early in childhood.

Midsagittal plane: Plane that divides the body vertically into equal left and right halves. It is also called the medial plane, because it occurs on the midline of the body.

Molars: Teeth with flatter cusps that are used to grind food prior to swallowing.

Nasal aperture: Anterior opening of the nasal cavity.

Nasal bone: Paired bones that form the bridge of the nose and the roof of the nasal cavity.

Nasal spine: Bony projection from the inferior part of the nasal aperture.

Neurocranium: Bones of the cranium that protects the brain.

Nuchal lines: Ridges on occipital from attachment of neck and back muscles.

Obturator foramen: Irregularly shaped opening within the pubis and ischium.

Occipital bone: Unpaired bone at the posterior and base of the skull.

Occlusal: Toward the chewing surface.

Olecranon process: Posterior projection of the proximal ulna.

Orbit: Bony cavity that houses the eye and associated structures.

Os coxa: Hip bone, forms from the fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis.

Osteoblast: Cell that secretes the matrix for bone formation.

Osteoclast: A multinucleated bone cell that resorbs bone tissue during growth and repair.

Osteocyte: Mature bone cell that lies within the bone matrix.

Osteogenic cells: Stem cells that differentiate into osteoblasts.

Osteology: The study of bones.

Palatine bone: Paired bones that form the posterior part of the hard palate.

Parasagittal plane: A vertical imaginary line adjacent to the sagittal plane that divides the body into unequal halves.

Parietal bone: Paired bones forming the lateral walls of the cranium.

Patella: Knee cap; a bone that forms in the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle.

Pedicle: Projection that connects the lamina to the centrum.

Phalanges: The 14 bones of the digits.

Posterior (or dorsal): Toward the back.

Premolars: Teeth with two rounded cusps that are used to grind and mash a food item.

Proximal: Closer to the center of the body or point of attachment.

Pterygoid plates: Flat projections of the sphenoid that serve as attachment sites for chewing muscles and muscles of the throat.

Pubic symphysis: Joint surface that unites the two pubic bones anteriorly.

Pubis: Anterior and inferior portion of the coxa.

Radial tuberosity: Rough projection for attachment of biceps brachii muscle.

Radius: Lateral bone of the forearm.

Ramus of the mandible: Bar-like portion of the posterior mandible.

Rib tubercle: Posterior part of the rib that articulates with the transverse process.

Sacrum: Triangular bone at the base of the spine that consists of 5 fused vertebrae.

Sagittal plane: An imaginary line that divides the body into left and right halves.

Sagittal suture: Joint that connects the parietal bones.

Scapula: Flat, triangular bone that connects the upper limb to the pectoral girdle.

Sesamoid bone: Bones that form within a tendon.

Short bone: Bones that are as wide as they are long.

Sphenoid bone: Unpaired bone that forms the anterior part of the base of the skull.

Spine: Elongated ridge on posterior surface.

Spinous process: Posterior projection of vertebral arch at the junction of the lamina.

Squamosal suture: Joint that connects the parietal and temporal bones.

Sternal end of the rib: Anterior part of rib that connects to the sternal body through costal cartilage.

Sternum: Breastbone; flat bone of the anterior chest wall.

Styloid process: Thin projection from the base of the temporal bone.

Styloid process of radius: Projection from the distal radius.

Styloid process of ulna: Projection from the distal ulna.

Subpubic concavity: Depression below the pubic symphysis to the ischiopubic rami.

Superior (or cranial): Toward the head.

Superior articular process: Superior projections from the vertebral arch that connect to inferior articular processes of the superior vertebra.

Supraorbital margin: External ridge at the superior part of the orbit.

Talus: Ankle bone that articulates with the tibia.

Tarsal bones: The 7 bones at the proximal end of foot; talus, calcaneus, navicular, cuneiforms (medial, intermediate, lateral), and cuboid.

Temporal bone: Paired bones at the lateral and base of the skull that contain the middle and inner ear.

Temporal lines: Ridges on the parietal bone from attachments of temporalis muscle and fascia.

Temporal process of zygomatic bone: Long process that forms the anterior half of the zygomatic arch.

Thoracic region: Trunk region that consists of 12 vertebrae that attach to ribs.

Tibia: Medial bone of the leg.

Tibial tuberosity: Roughened attachment site on the anterior surface of the proximal tibia.

Transverse plane: An imaginary line that divides the body into superior and inferior halves.

Transverse process: Lateral projection at the junction of the pedicle and lamina.

Ulna: Medial bone of the forearm.

Vertebral arch: Circular ring of bone at the posterior vertebra.

Vertebral canal: Cavity that contains the spinal cord.

Vertebral foramen: Opening formed by the vertebral arch.

Viscerocranium: Bones of the cranium that make up the face skeleton.

Vomer: Unpaired bone that forms the inferior part of the bony nasal septum.

Xiphoid process: Lower part of the sternum.

Zygapophyseal (facet) joints: Synovial joints between the superior and inferior articular processes.

Zygomatic arch: Bridge of bone at the cheek.

Zygomatic bone: Paired bones that form the anterior and lateral parts of the mid-face.

Zygomatic process of temporal bone: Long process that forms the posterior half of the zygomatic arch.

Zygomatic process of the maxilla: Portion of the bone that articulates with the zygomatic bone to form the anterior portion of the zygomatic arch.

About the Authors

Jason M. Organ, Ph.D.

Indiana University School of Medicine, jorgan@iu.edu

Jason M. Organ is an associate professor of anatomy, cell biology, and physiology at the Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) and Editor-in-Chief of Anatomical Sciences Education, the premier peer-reviewed journal for anatomy education research. Jason earned an M.A. in anthropology from the University of Missouri and a PhD in functional anatomy and evolution from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and he completed a postdoctoral research fellowship in physical medicine and rehabilitation at the Johns Hopkins Kennedy Krieger Institute. He is the director of the IUSM clinical anatomy and physiology M.S. program and was the 2018 recipient of the prestigious Basmajian Award from the American Association for Anatomy for excellence in teaching gross anatomy and outstanding accomplishments in biomedical research and scholarship in education. Follow him on Twitter: @OrganJM.

Jessica N. Byram, Ph.D.

Indiana University School of Medicine, jbyram@iu.edu

Jessica N. Byram is an assistant professor of anatomy, cell biology, and physiology at the Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM). Jessica earned her M.S. in human biology with a focus in forensic anthropology from the University of Indianapolis and her Ph.D. in anatomy education at IUSM. Jessica is the director of the anatomy education track Ph.D. program at IUSM. Her research interests include medical professionalism, investigating professional identity formation in medical students and residents, and exploring how to improve the learning environments at medical institutions.

References

Bass, William M. 2005. Human Osteology: A Laboratory and Field Manual, 5th edition. Columbia, MO: Missouri Archaeological Society.

Boldsen, Jesper L., George R. Milner, Lyle W. Konigsberg, and James W. Wood. 2002. “Transition Analysis: A New Method for Estimating Age from Skeletons.” In Paleodemography: Age Distributions from Skeletal Samples, edited by Robert D. Hoppa and James W. Vaupel, 73–106. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Buikstra, Jane E., and Douglas H. Ubelaker. 1994. Standards for Data Collection From Human Skeletal Remains. Arkansas Archaeological Survey Research Series, 44. Fayetteville, AR: Arkansas Archeological Survey.

Burr, David B., and Jason M. Organ. 2017. “Postcranial Skeletal Development and Its Evolutionary Implications.” In Building Bones: Bone Formation and Development in Anthropology, edited by Christopher J. Percival and Joan T. Richtsmeier, 148–174. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Christensen, Angi M., Nicholas V. Passalacqua, and Eric J. Bartelink. 2019. Forensic Anthropology: Current Methods and Practice. London: Academic Press.

Cunningham, Craig, Louise Scheuer, and Sue Black. 2017. Developmental Juvenile Osteology, 2nd Edition. London: Elsevier.

Hartnett, Kristen M. 2010 “Analysis of Age-at-Death Estimation Using Data from a New, Modern Autopsy Sample—Part II: Sternal End of the Fourth Rib. Journal of Forensic Sciences 55 (5): 1152–1156.

Meindl, Richard S., and C. Owen Lovejoy. 1985. “Ectocranial Suture Closure: A Revised Method for the Determination of Skeletal Age at Death Based on the Lateral-Anterior Sutures.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 68 (1): 57–66.

Nawrocki, Stephen P., Krista E. Latham, Thomas Gore, Rachel M. Hoffman, Jessica N. Byram, and Justin Maiers. 2018. “Using Elliptical Fourier Analysis to Interpret Complex Morphological Features in Global Populations.” In New Perspectives in Forensic Human Skeletal Identification, edited by Krista E. Latham, Eric J. Bartelink, and Michael Finnegan, 301–312. London: Elsevier/Academic Press.

Walker, Phillip L. 2008. “Sexing Skulls Using Discriminant Function Analysis of Visually Assessed Traits.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 136 (1): 39–50.

Image Description

Figure A.1: This illustration depicts an anterior view of the right femur, or thigh bone. The inferior end that connects to the knee is at the bottom of the diagram and the superior end that connects to the hip is at the top of the diagram. The bottom end of the bone contains a smaller lateral bulge and a larger medial bulge. A blue articular cartilage covers the inner half of each bulge as well as the small trench that runs between the bulges. This area of the inferior end of the bone is labeled the distal epiphysis. Above the distal epiphysis is the metaphysis, where the bone tapers from the wide epiphysis into the relatively thin shaft. The entire length of the shaft is the diaphysis. The superior half of the femur is cut away to show its internal contents. The bone is covered with an outer translucent sheet called the periosteum. At the midpoint of the diaphysis, a nutrient artery travels through the periosteum and into the inner layers of the bone. The periosteum surrounds a white cylinder of solid bone labeled compact bone. The cavity at the center of the compact bone is called the medullary cavity. The inner layer of the compact bone that lines the medullary cavity is called the endosteum. Within the diaphysis, the medullary cavity contains a cylinder of yellow bone marrow that is penetrated by the nutrient artery. The superior end of the femur is also connected to the diaphysis by a metaphysis. In this upper metaphysis, the bone gradually widens between the diaphysis and the proximal epiphysis. The proximal epiphysis of the femur is roughly hexagonal in shape. However, the upper right side of the hexagon has a large, protruding knob. The femur connects and rotates within the hip socket at this knob. The knob is covered with a blue colored articular cartilage. The internal anatomy of the upper metaphysis and proximal epiphysis are revealed. The medullary cavity in these regions is filled with the mesh-like spongy bone. Red bone marrow occupies the many cavities within the spongy bone. There is a clear, white line separating the spongy bone of the upper metaphysis with that of the proximal epiphysis. This line is labeled the epiphyseal line.”

Figure A.2: On the left side is an anterior view of a complete human skeleton. PRojecting from it to the right are six different colored rows with six functions of the human skeleton and a smaller corresponding image:

- Protects internal organs (image of crania with brain inside)

- Stores and releases fat (image of the proximal half of a femur with yellow marrow drawn in the shaft’s medullary cavity and red specs in the cancellous bone of the proximal femur.

- Produces blood cells (image of red blood cells)

- Stores and releases minerals (image of bubbles with either Ca2+ or PO43- written on them.)

- Facilitates movement (image of the bones in a knee)

- Supports the body (image of the lower leg and foot bones)

Figure A.3: This illustration shows an anterior view of a human skeleton with call outs of five bones. The first call out is the sternum, or breast bone, which lies along the midline of the thorax. The sternum is the bone to which the ribs connect at the front of the body. It is classified as a flat bone and appears somewhat like a tie, with an enlarged upper section and a thin, tapering, lower section. The next callout is the right femur, which is the thigh bone. The inferior end of the femur is broad where it connects to the knee while the superior edge is ball-shaped where it attaches to the hip socket. The femur is an example of a long bone. The next callout is of the patella or kneecap. It is a small, wedge-shaped bone that sits on the anterior side of the knee. The kneecap is an example of a sesamoid bone. The next callout is a dorsal view of the right foot. The lateral, intermediate and medial cuneiform bones are small, square-shaped bones of the top of the foot. These bones lie between the proximal edge of the toe bones and the inferior edge of the shin bones. The lateral cuneiform is proximal to the fourth toe while the medial cuneiform is proximal to the great toe. The intermediate cuneiform lies between the lateral and medial cuneiform. These bones are examples of short bones. The fifth callout shows a superior view of one of the lumbar vertebrae. The vertebra has a kidney-shaped body connected to a triangle of bone that projects above the body of the vertebra. Two spines project off of the triangle at approximately 45 degree angles. The vertebrae are examples of irregular bones.

Figure A.4: The top of this diagram shows the cross section of a generic bone with three zoom in boxes. The first box is on the periosteum. The second box is on the middle of the compact bone layer. The third box is on the inner edge of the compact bone where it transitions into the spongy bone. The callout in the periosteum points to two images. In the first image, four osteoblast cells are sitting end to end on the periosteum. The osteoblasts are roughly square shaped, except for one of the cells which is developing small, finger like projections. The caption says, “Osteoblasts form the matrix of the bone.” The second image called out from the periosteum shows a large, amorphous osteogenic cell sitting on the periosteum. The osteogenic cell is surrounded on both sides by a row of much smaller osteoblasts. The cell is shaped like a mushroom cap and also has finger like projections. The cell is a stem cell that develops into other bone cells. The box in the middle of the compact bone layer is pointing to an osteocyte. The osteocyte is a thin cell, roughly diamond shaped, with many branching, finger-like projections. The osteoctyes maintain bone tissue. The box at the inner edge of the compact bone is pointing to an osteoclast. The osteoclast is a large, round cell with multiple nuclei. It also has rows of fine finger like projections on its lower surface where it is sitting on the compact bone. The osteoclast reabsorbs bone.

Figure A.5: Image A shows seven osteoblasts, cells with small, finger like projections. They are surrounded by granules of osteoid. Both the cells and the osteoid are contained within a blue, circular, ossification center that is surrounded by a “socket” of dark, string-like collagen fibers and gray mesenchymal cells. The cells are generally amorphous, similar in appearance to an amoeba. In image B, the ossification center is no longer surrounded by a ring of osteoblasts. The osteoblasts have secreted bone into the ossification center, creating a new bone matrix. There are also five osteocytes embedded in the new bone matrix. The osteocytes are thin, oval-shaped cells with many fingerlike projections. Osteoid particles are still embedded in the bony matrix in image B. In image C, the ring of osteoblasts surrounding the ossification center has separated, forming an upper and lower layer of osteoblasts sandwiched between the two layers of mesenchyme cells. A label indicates that the mesenchyme cells and the surrounding collagen fibers form the periosteum. The osteoblasts secrete spongy bone into the space between the two osteoblast rows. Therefore, the accumulating spongy bone pushes the upper and lower rows of osteoblasts away from each other. In this image, most of the spongy bone has been secreted by the osteoblasts, as the trabeculae are visible. In addition, an artery has already broken through the periosteum and invaded the spongy bone. Image D looks similar to image C, except that the rows of osteoblasts are now secreting layers of compact bone between the spongy bone and the periosteum. The artery has now branched and spread throughout the spongy bone. A label indicates that the cavities between the trabeculae now contain red bone marrow.

Figure A.6: Image A shows a small piece of hyaline cartilage that looks like a bone but without the characteristic enlarged ends. The hyaline cartilage is surrounded by a thin perichondrium. In image B, the hyaline cartilage has increased in size and the ends have begun to bulge outwards. A group of dark granules form at the center of the cartilage. This is labeled the calcified matrix, as opposed to the rest of the cartilage, which is uncalcified matrix. In image C, the hyaline cartilage has again increased in size and spongy bone has formed at the calcified matrix. This is now called the primary ossification center. A nutrient artery has invaded the ossification center and is growing through the cavities of the new spongy bone. In image D, the cartilage now looks like a bone, as it has greatly increased in size and each end has two bulges. Only the proximal half of the bone is shown in all of the remaining images. In image D, spongy bone has completely developed in the medullary cavity, which is surrounded, on both sides, by compact bone. Now, the calcified matrix is located at the border between the proximal metaphysis and the proximal epiphysis. The epiphysis is still composed of uncalcified matrix. In image E, arteries and veins have now invaded the epiphysis, forming a calcified matrix at its center. This is called a secondary ossification center. In image F, the interior of the epiphysis is now completely calcified into bone. The outer edge of the epiphysis remains as cartilage, forming the articular cartilage at the joint. In addition, the border between the epiphysis and the metaphysis remains uncalcified, forming the epiphyseal plate.

Figure A.8: This illustration shows a female viewed from her right, front side. The anatomical planes are depicted as blue rectangles passing through the woman’s body. The frontal or coronal plane enters through the right side of the body, passes through the body, and exits from the left side. It divides the body into front (anterior) and back (posterior) halves. The sagittal plane enters through the back and emerges through the front of the body. It divides the body into right and left halves. The transverse plane passes through the body perpendicular to the frontal and sagittal planes. This plane is a cross section which divides the body into upper and lower halves.

Figure A.10: This diagram shows the human skeleton and identifies the major bones. The left panel shows the anterior view (from the front) and the right panel shows the posterior view (from the back).

Figure A.11: In this image, the lateral view of the human skull is shown and the brain case and facial bones are labeled.

Figure A.12: This image shows the anterior view (from the front) of the human skull. The major bones on the skull are labeled.

Figure A.13: This image shows the lateral view of the human skull and identifies the major parts.

Figure A.14: This image shows the location of the temporal bone. A small image of the skull on the top left shows the temporal bone highlighted in pink and a magnified view of this region then highlights the important parts of the temporal bone.

Figure A.15: This image shows the superior and inferior view of the skull base. In the top panel, the inferior view is shown. A small image of the skull shows the viewing direction on the left. In the inferior view, the maxilla and the associated bones are shown. In the bottom panel, the superior view shows the ethmoid and sphenoid bones and their subparts.

Figure A.16: This image shows the location and structure of the sphenoid bone. A small image of the skull on the top left shows the sphenoid bone highlighted in ochre yellow. The top panel shows the superior view of the sphenoid bone and the bottom panel shows the posterior view of the sphenoid bone.

Figure A.17: This image shows the location and structure of the ethmoid bone. A small image of the skull on the top left shows the ethmoid bone colored in pink. A magnified image shows the inferior view of the ethmoid bone.

Figure A.18: This image shows the location and structure of the maxilla. A small image of the skull on the top left shows the maxilla in ochre yellow. A magnified view shows the detailed structure of the maxilla.

Figure A.19: In this image, the different bones forming the orbit for the eyes are shown and labeled.

Figure A.20: This image shows the sagittal section of the bones that comprise the nasal cavity.

Figure A.21: This figure shows the structure of the nasal cavity. A lateral view of the human skull is shown on the top left with the nasal cavity highlighted in purple. A magnified view of the nasal cavity shows the various bones present and their location.

Figure A.22: In this image, the location and structure of the hyoid bone are shown. The top panel shows a person’s face and neck, with the hyoid bone highlighted in gray. The middle panel shows the anterior view and the bottom panel shows the right anterior view.

Figure A.23: This image shows the structure of the mandible. On the top left, a lateral view of the skull shows the location of the mandible in purple. A magnified image shows the right lateral view of the mandible with the major parts labeled.

Figure A.24: This image shows the detailed structure of each vertebra. The left panel shows the superior view of the vertebra and the right panel shows the left posterolateral view.

Figure A.25: This figure shows the structure of the cervical vertebrae. The left panel shows the location of the cervical vertebrae in green along the vertebral column. The middle panel shows the structure of a typical cervical vertebra and the right panel shows the superior and anterior view of the axis.

Figure A.26: This diagram shows how the thoracic vertebra connects to the angle of the rib. The major parts of the vertebra and the processes connecting the vertebra to the rib are labeled.

Figure A.27: This figure shows the structure of the thoracic vertebra. The left panel shows the vertebral column with the thoracic vertebrae highlighted in blue. The right panel shows the detailed structure of a single thoracic vertebra.

Figure A.28: This figure shows the structure of the sacrum and coccyx. The left panel shows the vertebral column with the sacrum and coccyx highlighted in pink. The middle panel shows the anterior view and the right panel shows the posterior view of the sacrum and coccyx.

Figure A.29: This image shows the structure of the vertebral column. The left panel shows the front view of the vertebral column and the right panel shows the side view of the vertebral column.

Figure A.30: This figure shows the skeletal structure of the rib cage. The left panel shows the anterior view of the sternum and the right panel shows the anterior panel of the sternum including the entire rib cage.

Figure A.31: This figure shows the rib change. The top left panel shows the anterior view, and the top right panel shows the posterior view. The bottom panel shows two bones.

Figure A.32: This diagram shows the anterior and posterior view of the scapula.

Figure A.33: This diagram shows the bones of the upper arm and the elbow joint. The left panel shows the anterior view, and the right panel shows the posterior view.

Figure A.34: This figure shows the bones of the lower arm.

Figure A.35: This figure shows the bones in the hand and wrist joints. The left panel shows the anterior view, and the right panel shows the posterior view.

Figure A.36: This figure shows the bone of the pelvis.

Figure A.37: This figure shows the right hip bone. The left panel shows the lateral view, and the right panel shows the medial view.

Figure A.38: This diagram shows the bones of the femur and the patella. The left panel shows the anterior view, and the right panel shows the posterior view.

Figure A.39: This diagram shows the bones of the tibia and the fibula. The left panel shows the anterior view, and the right panel shows the posterior view.

Figure A.40: This diagram shows the bones of the foot from three different perspectives. The upper right panel shows the medial view, the lower right panel shows the lateral view, and the bottom left shows the superior view.

The study of bones.

Dense, outer surface of bone.

Porous bone found at the ends of long bones and within flat and irregular bones.

Bones that are longer than they are wide.

Shaft or central part of a long bone.

Central cavity in the diaphysis of long bones that contains bone marrow.

End of long bones.

Junction between diaphysis and epiphysis where bone growth occurs.

Bones that are as wide as they are long.

Bones that are flat with thin layers of cortical bone surrounding cancellous bone.

Bones that form within a tendon.

Bones that have a complex appearance.

Mature bone cell that lies within the bone matrix.

A multinucleated bone cell that resorbs bone tissue during growth and repair.

Cell that secretes the matrix for bone formation.

Stem cells that differentiate into osteoblasts.

Process of bone formation that occurs in mesenchyme and gives rise to flat bones of the skull.

Process of bone formation that occurs from a cartilage model.

Standing upright, facing forward with arms at the side and palms facing forward.

An imaginary line that divides the body into anterior and posterior halves.

An imaginary line that divides the body into superior and inferior halves.

An imaginary line that divides the body into left and right halves.

Plane that divides the body vertically into equal left and right halves. It is also called the medial plane, because it occurs on the midline of the body.

A vertical imaginary line adjacent to the sagittal plane that divides the body into unequal halves.

Toward the front.

Toward the back.

Toward the midline.

Further away from the midline.

Closer to the center of the body or point of attachment.

Further away from the center of the body or point of attachment.

Toward the head.

Away from the head or downward.

Part of the skeleton that consists of the bones of the head and trunk.

Part of the skeleton that consists of the bones of the pectoral and pelvic girdls, arms, and legs.

Lower jaw bone.

Bones of the head that support the brain and face.

Bones of the cranium that protects the brain.

Bones of the cranium that make up the face skeleton.

Fibrous joints that connect bones of the skull and face.

An unpaired bone that forms the anterior and superior part of the cranium.

Bony cavity that houses the eye and associated structures.

Joint that connects the frontal bone to the paired parietal bones.

Joint that connects paired frontal bones and usually fuses early in childhood.

Part of the forehead between the eyebrows.

External ridge at the superior part of the orbit.

Paired bones forming the lateral walls of the cranium.

Joint that connects the parietal bones.

Ridges on the parietal bone from attachments of temporalis muscle and fascia.

Paired bones at the lateral and base of the skull that contain the middle and inner ear.

Joint that connects the parietal and temporal bones.

Bony projection from the back of the temporal bone.

Thin projection from the base of the temporal bone.

Long process that forms the posterior half of the zygomatic arch.

Bridge of bone at the cheek.

Depression at the base of the temporal bone where the mandibular condyle articulates to form the temporomandibular (or jaw) joint.

Unpaired bone at the posterior and base of the skull.

Joint that connects the parietal and occipital bones.

Projection from the occipital superior to nuchal lines.

Ridges on occipital from attachment of neck and back muscles.

Large opening in the occipital where the spinal cord passes.

Unpaired bone that forms the anterior part of the base of the skull.

Flat projections of the sphenoid that serve as attachment sites for chewing muscles and muscles of the throat.

Unpaired bone of the skull that separates the nasal cavity from the brain.

Small openings in the superior plate of the ethmoid that transmit olfactory nerves.

Upper jaw bone.

Bony projection from the inferior part of the nasal aperture.

Portion of the bone that articulates with the zygomatic bone to form the anterior portion of the zygomatic arch.

Paired bones that form the bridge of the nose and the roof of the nasal cavity.

Anterior opening of the nasal cavity.

Paired bones that form the anterior and lateral parts of the mid-face.

Long process that forms the anterior half of the zygomatic arch.

Paired bones that form the posterior part of the hard palate.

Paired bones that form the anterior and medial part of the orbit.

Unpaired bone that forms the inferior part of the bony nasal septum.

Scroll-like paired bones that attach to the lateral part of the nasal cavity.

U-shaped bone in the neck that does not articulate with another bone.

Triangular projection at the front of the mandible.

Bar-like portion of the posterior mandible.

Triangular eminence from the superior part of the mandibular ramus

Rounded projection of the mandibular ramus.

Posterior border of the mandible at the junction of the ramus and body.

The spatula-shaped teeth at the front of the mouth.

Conical teeth with a single pointed cusp used to puncture a food item.

The smallest of the hind teeth, behind the canines.

The largest teeth at the back of the mouth; used for chewing. In primates, these teeth usually have between three and five cusps.

Toward the middle.

Toward the cheek.

Toward the tongue.

the surface that comes in contact with food or the teeth from the other jaw when the jaw is closed

Toward the cutting edge.

Anterior body of vertebra; the main weight-bearing element of the vertebra.

Circular ring of bone at the posterior vertebra.

Lateral projection at the junction of the pedicle and lamina.

Flattened portion of the vertebral arch.

Posterior projection of vertebral arch at the junction of the lamina.

Inferior projections from the vertebral arch that connect to superior articular processes of the inferior vertebra.

Superior projections from the vertebral arch that connect to inferior articular processes of the superior vertebra.

Opening formed by the vertebral arch.

Fibrocartilaginous joints that connect adjacent centra of vertebrae.

Synovial joints between the superior and inferior articular processes.

Cavity that contains the spinal cord.

Neck region that contains 7 vertebrae.

Joint between the atlas (C1 vertebrae) and occipital bone, used for nodding the head.

Projection from superior surface of centrum of C2.

Projection from superior surface of centrum of C2.

Joint between the atlas (C1 vertebrae) and the axis (C2 vertebrae), used for turning the head side to side.

Trunk region that consists of 12 vertebrae that attach to ribs.

Partial joint surfaces on the lateral surface of the centrum of thoracic vertebrae.

Lower back region that consists of 5 vertebrae.

Triangular bone at the base of the spine that consists of 5 fused vertebrae.

Small triangular bone that projects from the inferior part of sacrum.

Anterior curvature of the spine.

Posterior curvature of the spine.

Breastbone; flat bone of the anterior chest wall.

Upper part of the sternum.

Central portion of the sternum where ribs articulate.

Lower part of the sternum.

Posterior part of the rib that articulates with the transverse process.

Posterior part of the rib that articulates with the centrum.

Anterior part of rib that connects to the sternal body through costal cartilage.

The collarbone, which connects the sternum to the scapula to form the pectoral girdle.

Flat, triangular bone that connects the upper limb to the pectoral girdle.

Shallow depression for the articulation of the head of the humerus.

Hook-shaped projection from the anterior surface of the scapula.

Lateral projection of the spine of scapula.

Elongated ridge on posterior surface.

Long bone of the arm.

Large projection on the superior and lateral surface of the humerus.

Lateral projection for attachment of deltoid muscle.

Lateral bone of the forearm.

Rough projection for attachment of biceps brachii muscle.

Projection from the distal radius.

Medial bone of the forearm.

Projection from the distal ulna.

Bony projection at the elbow end of the ulna.

The 8 bones of the wrist: scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, pisiform, trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate.

The 5 bones of the palm of the hand.

The 14 bones of the digits.

Hip bone, forms from the fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis.

Shallow cavity of the coxa for articulation of the head of the femur.

Large flat bone of the superior part of the coxa.

Roughened joint surface for articulation of the sacrum.

Large indentation of the ilium.

The posterior and inferior portion of the os coxae.

Thin, square projection from the ischium.

Large, round protrusion of the posterior and inferior ischium.

Anterior and inferior portion of the coxa.

Superior bar of the pubis.

Thin bar of bone that unites the pubis and ischium.

A joint that joins the left and right halves of the pelvis anteriorly.

Depression below the pubic symphysis to the ischiopubic rami.

Irregularly shaped opening within the pubis and ischium.

The 5 bones at the distal part of the foot.

Long bone of the thigh.

Large projection from the lateral surface of the proximal femur.

Projection from the medial surface of the proximal femur.

Roughened attachment site for the gluteus maximus muscle.

Elongated projection of the posterior surface of the femur.

Knee cap; a bone that forms in the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle.

Medial bone of the leg.

Lateral bone of the leg.

Roughened attachment site on the anterior surface of the proximal tibia.

Prominence of the distal tibia that forms the inner part of the ankle.

Prominence of the distal fibula that forms the outer part of the ankle.

The 7 bones at the proximal end of foot; talus, calcaneus, navicular, cuneiforms (medial, intermediate, lateral), and cuboid.

Ankle bone that articulates with the tibia.

Large bone that forms the heel.

Roughened attachment site at the posterior calcaneus.