7 Sex

Introduction

Sex is among the most powerful elements of human lives – indeed of the lives of just about all animal species. It allows us to reproduce, and thereby to continue our family lines, communities, and species, but also arouses passions, motivates actions, influences the structure of societies, expresses power dynamics, and, of course, inspires a great deal of art. In this chapter, we will consider works that treat the interrelated subjects of sex, sexuality, and gender from a range of perspectives. Some are celebratory, some ambivalent, and some outright condemnatory. While some of the works covered are tame and modest in their approach to representing or implying sexual activities, others are explicit. Images from Prehistory, Ancient Greece, Rome and Peru, Renaissance Germany and Italy, nineteenth-century France, medieval India, Edo Japan, and the contemporary period showcase a rich range of responses the theme of sex elicits in artists and viewers throughout the world’s history. It is worth noting that this is a subject that many art appreciation and art history textbook authors and publishers shy away from. Indeed, two publishers stated that this chapter could not be included in a work that they would publish! But I do not believe that any account of the world’s art can claim to be anything close to complete – or even honest – if it ignores a theme that has been absolutely central in art-making from the earliest of prehistoric cave paintings straight on through to the contemporary world.

SPOTLIGHT IMAGE I:

KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI, KINOE-NO-KOMATSU (PINING FOR LOVE), EDO, JAPAN, 1814 CE

VIEWING QUESTIONS

- What elements of the image draw the eye first?

- How do the colors affect the images?

- How do the images imply textures?

- How does scale impact the scenes?

PICTURES OF SPRING

In Edo Japan (1615–1868), erotic art was popular, and some of the most prominent artists of the period produced highly graphic works. These works are known as shunga, meaning “pictures of spring,” since “spring” was a euphemism for sex at the time. There is, though, nothing allusive about many shunga images, which range from gently erotic images of clothed courtesans to scenes of wild orgies, bestiality, and even scenes of sex with supernatural creatures, none of which were condemned in their day as obscene. The most common medium for shunga was Ukiyo-e, a colored woodblock printing medium that allowed artists to produce inexpensive works for a large market while still maintaining high standards of beauty and delicacy. Ukiyo-e literally means “pictures of the floating world” – a reference to the active red-light district of the capital city of Kyoto, and this term indicates how central the world of geishas, actors, sumo-wrestlers, and other inhabitants of “the floating world” were to the much-celebrated art of Edo Japan.

VISUAL ELEMENTS

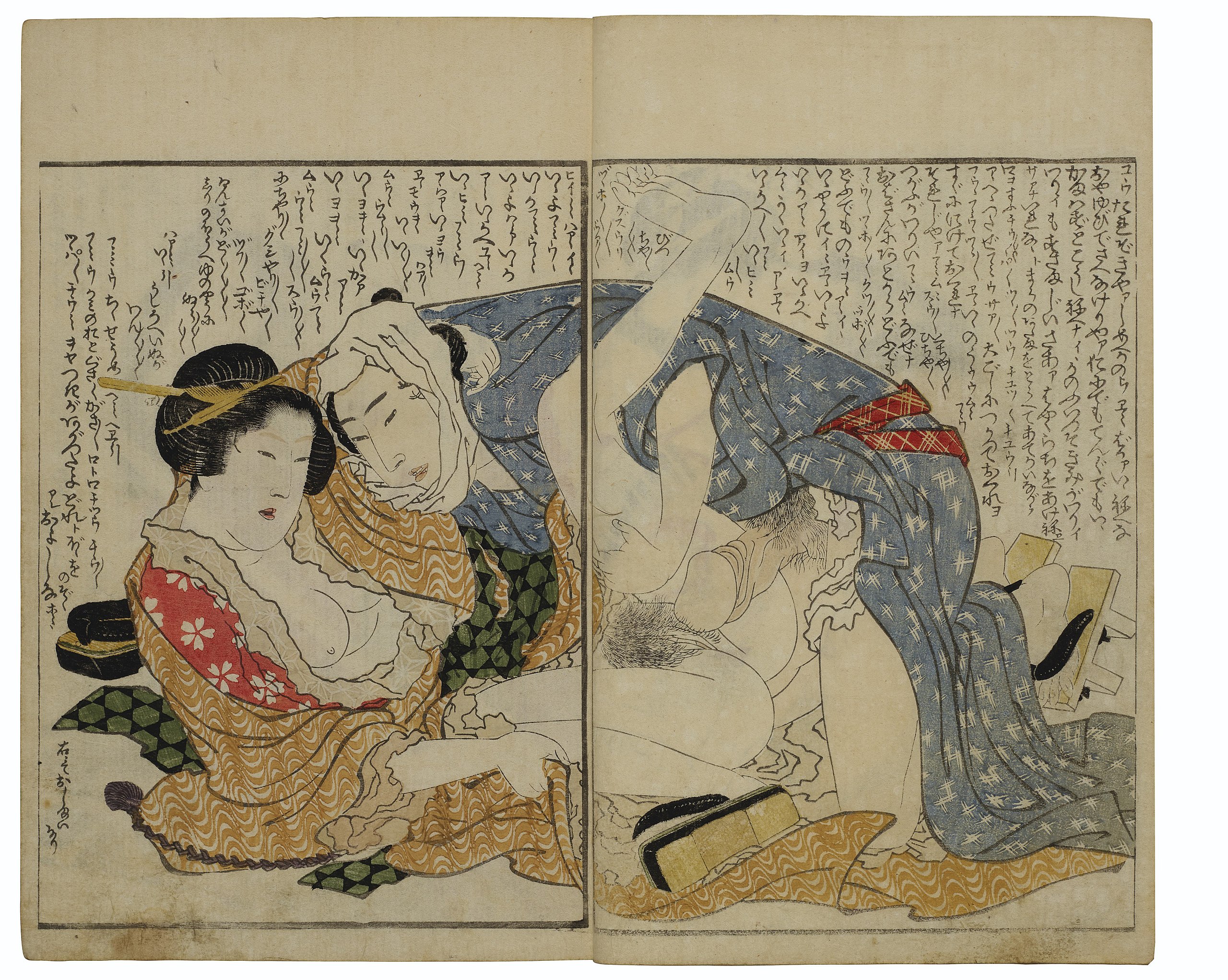

Ukiyo-e master Katsushika Hokusai produced several shunga albums, including his Kinoe-no-komatsu (Pining for Love). This section considers a few images from this album. The first depicts a couple about to engage in intercourse. They are both elaborately dressed, particularly the woman, whose layers of robes are pulled open to reveal her breast and hiked up to reveal her legs and genitals. The man’s robes are similarly pulled up to reveal his highly exaggerated erect penis, which is almost the size of his forearm – a standard feature of shunga prints. The woman reaches around the man’s neck as if both to pull herself upward and to pull him in closer to her. Both figures’ mouths are parted as they seem to pant with excitement and anticipation.

The woman’s robes consist of three layers, the innermost of which is ruffled into quite fleshy folds and colored in a soft pink. The openings this fabric frame become yonic – that is, they resemble a vulva – and her limbs – especially her right arm – emerging from these folds seem to echo the main action of the scene.

The couple is positioned so as to give the viewer the fullest view of the couple’s genitals. The man kneels behind rather than between the woman’s legs, which he holds open apparently as much for the viewer’s gaze as for his own comfort. Still, the image does not focus exclusively on the sexual act about to occur. Hokusai includes small details that fill out the scene, to give it greater specificity and therefore more individuality. For example, while the man still wears both of his sandals, the woman seems to have lost one, which sits behind her. Perhaps we are to assume that it fell off her left foot when she raised it up over her head. This is a charming, even comic detail to include in what is nonetheless a highly explicit image of sex.

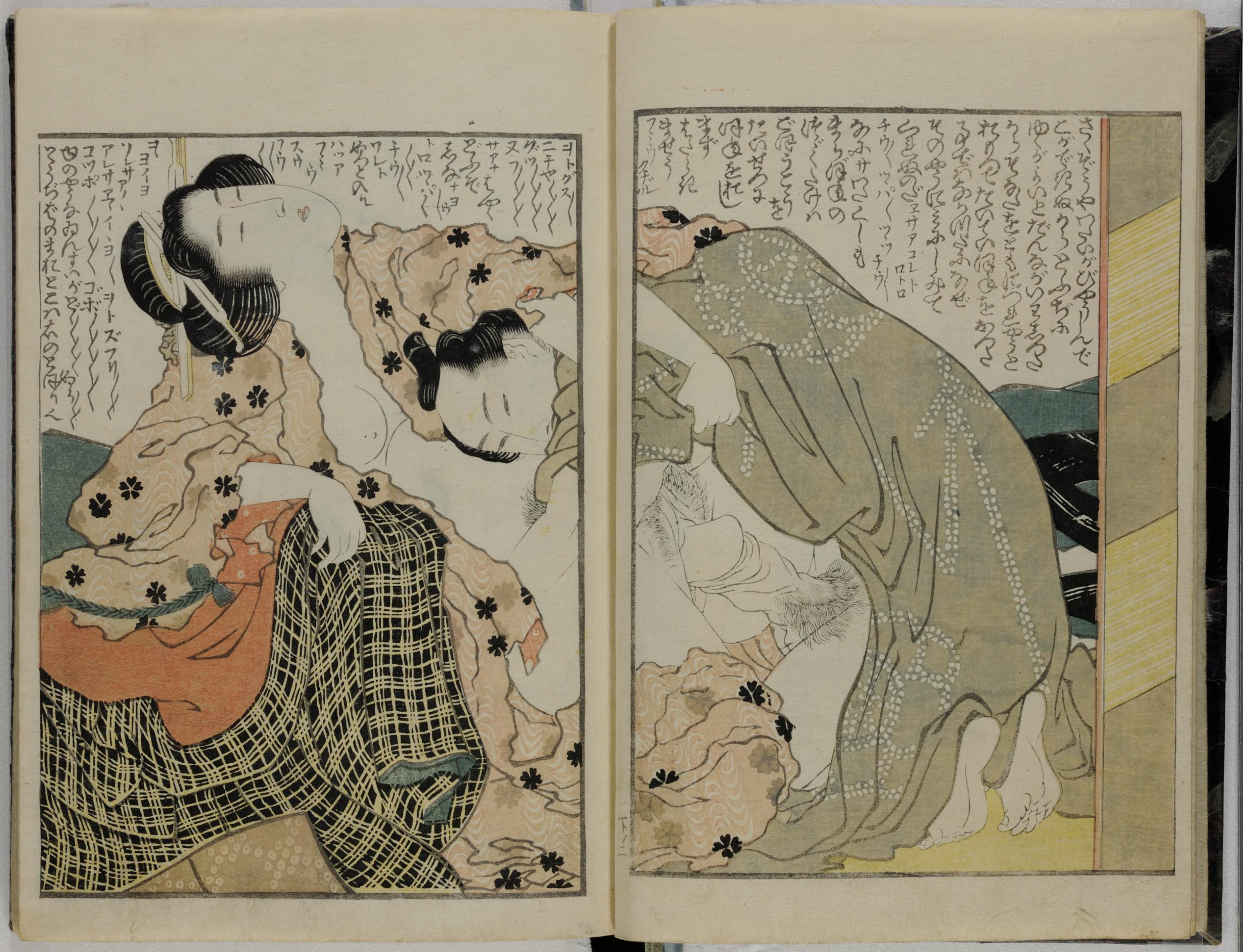

In another image from Kinoe-no-komatsu, we see a very similarly posed couple. The differences between the images are interesting. In the second image, the woman’s legs seem to be bent back and the knees, so that her lower legs and feet are not visible. The man’s feet are both bare. The colors are more muted, mostly in fleshy tones of beiges, browns, and pinks, which allow everything within the scene to blend smoothly together. Again, the figures are each partially clothed, but their robes are more fully pulled open, revealing their similarly exaggerated genitals.

Hokusai depicts this couple just at the moment of penetration. The man looks downward, as if to watch as his oversized penis enters into the woman, and the implied line of his gaze further directs ours to their genitals. The woman, on the other hand, tips her head back. Her eyes are almost closed, as if she is lost in the moment of pleasure. Her lips are parted and her teeth are just visible. She reaches out with her left hand to grasp her partner’s robes, as if to pull him toward her. Despite the apparent focus on the figures’ exaggerated genitals, Hokusai again includes details that humanize the lovers. The man’s feet, revealed at the base of his robes, the tension in the woman’s hands, the closeness of their bodies, and the fervor with which they seem to press together all stress their humanity and their deeply human passions.

They are surrounded by cascading waves of rumpled fabric, indicating the layers that needed to be removed to bring the couple to this point. They are also framed by the inscriptions that, through their energetic and trembling execution, as well as their content, convey some of the passion of the scene. While the image is openly erotic, it is not exclusively pornographic in nature, not intended to function solely within a visceral realm. Instead, the delicacy of execution allows the scene to appeal to the viewer above and beyond its potential ability to arouse. Indeed, some of the scenes within the album are either so unpleasant or outright bizarre that it seems unlikely that their primary function was to inspire sexual arousal.

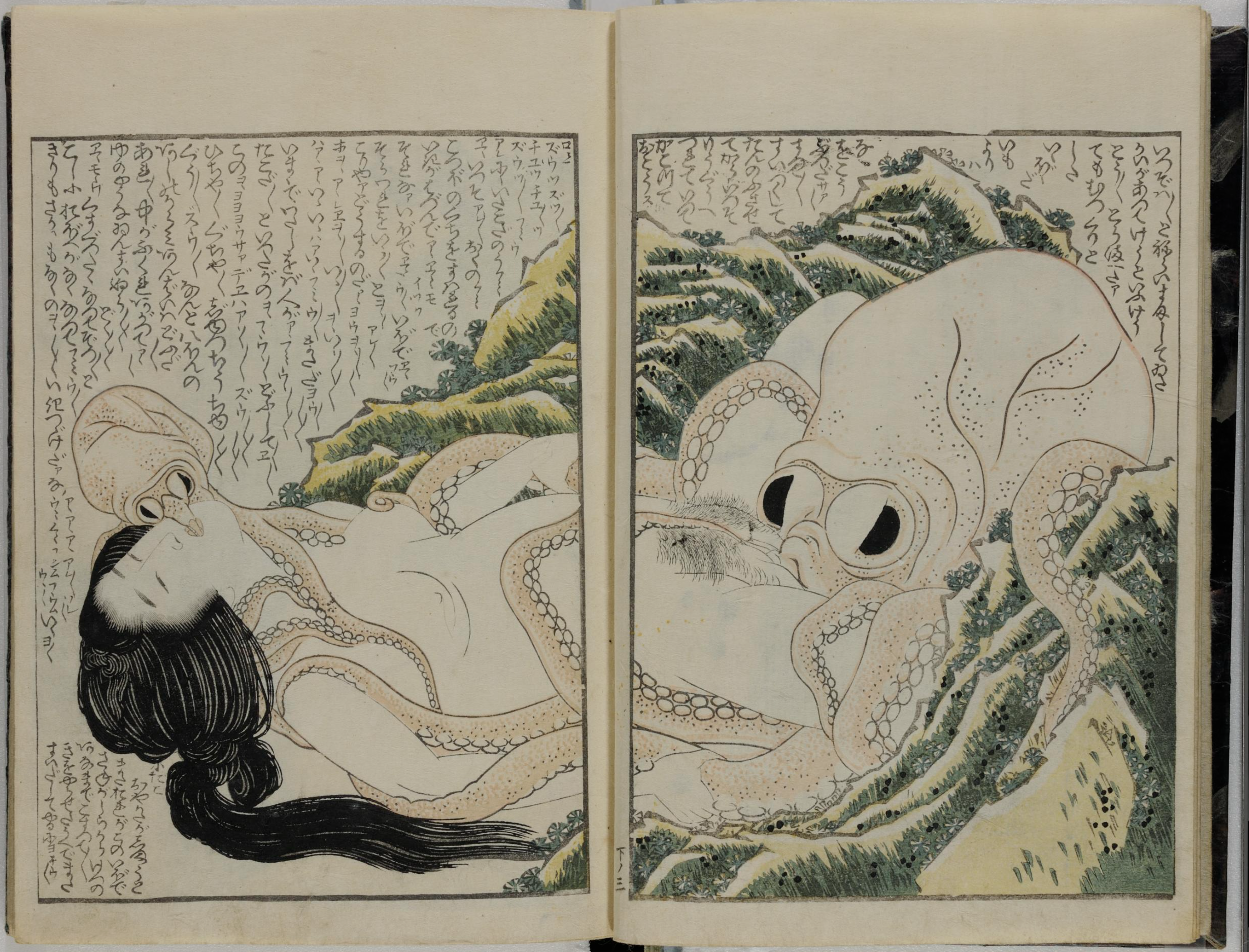

On what is the most well-known page of the album – indeed, one of the most well known works of Ukiyo-e – we find a startling scene: titled Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, it features a fully nude woman reclining on her back between the mossy, flower-filled rocks at the water’s edge while a giant, monstrous octopus performs oral sex on her. Its long, sinuous tentacles wrap around her body, the suckers along their length perhaps suggesting through their repetition the act being performed. A second, smaller octopus seems to be performing a sort of French kiss with her lips, as she tilts her head back and opens her mouth to reach out to it with her tongue, colored in just the same peachy pink as the octopuses.

The creatures are enveloping the woman, running tentacles up her sides, over her legs and torso, cradling the back of her neck. One small tentacle even curls around her left nipple. This is a curious sort of fantasy scene of bestial or monstrous sex. Still, while we might expect this to be a scene of violence or even horror, instead we find the woman responding with pleasure – as the title tells us, this is her dream, after all. She reaches out, holding onto the tentacles that run along her sides, not as if to resist but as if to pull her lover toward her, much in the same manner of the women in the two previous images. We should not forget, though, that while the fiction of the text tells us this is her fantasy, in fact both are the product of the male artist, constructing an image of female sexuality as wild and rapacious, first and foremost for a male audience’s interest.

Hokusai has moved the octopuses’ bulbous eyes to the fronts of their large heads, giving them a slightly more human appearance. This effect is furthered by the pale, peach tone he chose for their skin. They are clearly not human, of course, but with these small shifts in the appearance of the animals, they seem more sentient, and their actions therefore seem more willful, more human, as is also emphasized by the text, which grants them speech (discussed below).

The scene is given a minimal setting, as is perhaps fitting for such a fantasy. Rather than being sited in a carefully rendered location, the figures are loosely framed by the rocky shore, above and below. Its soft greens, yellows, and blues contrast with the pale peach and pink tones of the woman and the octopuses. The rocks are quite jagged, and therefore emphasize the smooth, graceful arcs of the figures’ bodies and limbs, and draw our attention to the smooth, unblemished texture of the woman’s exposed skin.

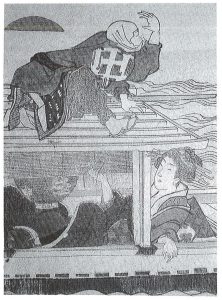

Shunga images were often sold as small packets of prints contained within a wrapper, as if in opening them the viewer was unveiling the erotic scenes within, or even undressing the characters depicted, heightening the erotic nature of the scenes themselves. Some shunga, including works tentatively attributed to Hokusai, take this a step further, incorporating the viewer’s participation in the process of the revelation of each image. Some surimono – privately commissioned prints produced in small runs to celebrate special occasions – for example, contain flaps that are printed separately and attached to the main image, to be closed or opened, thereby created tamer and more erotic images of the same scene.

A river scene, for example, shows a boatman greeting the rising sun – the print was commissioned as a new year’s card – while a woman reclines in the cabin beneath him. With the flap of this shikake-e (“trick-picture”) closed, we see her alone. With the flap removed, we see her with a lover. The blankness of her expression allows it to be read quite differently, depending on the position of the flap. This phenomenon is known as the Kuleshov Effect, named for Lev Kuleshov, a Russian filmmaker who experimented in the 1910s and 1920s. He showed viewers three pairs of film clips: A shot of a bowl of soup and then a close-up of current film icon Ivan Mosjoukine; an apparently dead girl in a coffin and then a close-up of Mosjoukine, and finally an alluring young woman reclining on a couch and then a close-up of Mosjoukine.

(Skip ahead to 1:00 in this video.)

Viewers assumed emotional connections, so that Mosjoukine was seen as pensive, sorrowful, and lustful, in turn, when in fact all three shots of Mosjoukine were identical, the same clip, repeated. So, too, the woman in Hokusai’s print seems pensive or bored with the flap closed, and aroused with it open. We invest our emotions into the figures in works of art, since these works are, of course, mere arrangements of lines and colors, not real people.

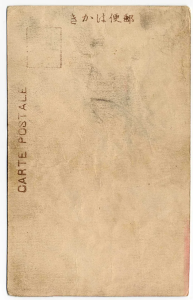

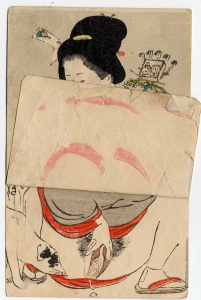

One final example, by an anonymous artist, further conveys the play at work in “trick” shikake-e prints. Yes, they are overtly sexual, but there is a kind of silliness, as well. In this case, the image is on a postcard which was never sent – the back was never filled out. Like so many postcards still sold at souvenir shops in tourist destinations, the content is playfully sexual, perhaps more than it is outright erotic (though, of course, the distinction is largely in the eye of the beholder). On the front of the postcard, in its initial position, we see a brightly-dressed woman holding a rake, as if she were simply out gardening. This anonymous work is far simpler in design and execution than works by Hokusai, with features only sketched in and forms far more generalized. This is more of a gag-gift, perhaps, than a fine print to be treasured. Still, the lovely colors enliven it.

In the card’s initial position, the woman seems to be looking demurely down, presumably at the yard she has been raking. However, with the flap lifted, we see an entirely different scene. The woman, apparently standing moments ago, is now squatting with her skirts hiked up while she masturbates while a dog sniffs at her. Unlike the shikake-e attributed to Hokusai, which forms complete and coherent images in either position, with the flap lifted on the postcard, the woman’s torso and face are largely blocked, covered by the blank back of the raised flap. (The reddish lines have transferred to the flap from the hidden image.) The woman’s outer robe is filled in grey here, rather than the rich purple from the outer image, and the rake becomes an inexplicable detail, a distraction from the revealed scene. The survival of many cheap shikake-e images – some of which are far more direct and explicit than any of the examples here – indicates their wide popularity in the period, especially give that they are all ephemera, that is, items designed to be enjoyed briefly and then tossed away.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

The Edo period spans the 250-year shogunate (rule by a shogun, or military dictator) of the family of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who took control of Japan in 1600. This was a period of relative peace and prosperity, but also of increasingly repressive rule. In order to keep control of the daimyo – the lesser lords who owned obedience to the shogun – the shoguns required that they spend half of their time in the capital city of Edo (present-day Tokyo). Buddhism was the main religion of Japan in the period, and it preached that the joys of the world were fleeting. Rather than following the stricter strains of Buddhist practice, the newly prosperous middle class of merchants, artisans and tradesmen thriving in Edo saw the transience of pleasure as a reason to seek it out, to enjoy life are richly as possible. They referred to the brief moment of joy in the world as ukiyo (“The Floating World”), and saw it as something to celebrate.

The culture of the capital was centered on the pleasure districts, home to teahouses, restaurants, brothels, bathhouses, theaters, and other entertainments. Actors and courtesans became the most famous and revered celebrities, and artists produced low-cost works of art for mass consumption by making woodblock prints.

Since one set of woodblocks can produce many copies of a print, artists were able to invest time and care in their production, but still sell them at prices that the middle class patrons of the pleasure district could afford. Many prints focus on just these pleasures, with head-shots of actors and courtesans, scenes from popular plays and sumo wrestling matches, tea shops, and, of course, sex.

Katsushika Hokusai was a contemporary of Ando Hiroshige, who also produced a few surviving shunga prints in his characteristically lavish style. These two artists were the central artists of the Edo period, and Hokusai is considered by some to be the most prominent artist from all of Asian history, and, given the vast chronological, geographical, and cultural extent of Asian history, this is a very substantial claim. Hokusai was not a minor figure, a second-rate artist producing cheap pornography. He was a celebrated master artist, and his production of shunga prints reveals a great deal about Edo Japan. In this period, shunga was not a marginalized or despised genre, but a prominent subject for artists to represent and patrons to consume. While the methods of publication emphasize secrecy and revelation, this is not due to shame but to a desire to heighten the sense of intimacy and titillation. Opening small, wrapped packages containing such scenes of erotic fantasy would have delayed contact with the image, and therefore elicited a stronger response once the image was revealed.

The texts that accompany Hokusai’s shunga prints have been criticized as lacking in the nuance and artistry of the images, and perhaps this is fair. The text surrounding the figures in Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, for example, is as absurd as the image, and as ecstatic, but also seems rather crude and direct. It consists of dialogue between the three participants, thereby granting human speech to the monstrous animals. At the same time, the woman’s speech breaks down into incoherent sounds of pleasure. In this way, the animals are elevated to a near-human status through their ability to speak, and the human is reduced to a more base state, as she loses hers in this cross-species encounter. An excerpt serves to convey the tone of the complete text text (bobo is a Japanese term for an octopus, but is also a Japanese slang term for the vulva):

LARGE OCTOPUS: My wish comes true at last, this day of days; finally I have you in my grasp! Your “bobo” is ripe and full, how wonderful! Superior to all others! To suck and suck and suck some more…

MAIDEN: You hateful octopus! Your sucking at the mouth of my womb makes me gasp for breath! Aah! yes… it’s…there!!! With the sucker, the sucker!! Inside, squiggle, squiggle, oooh! Oooh, good, oooh good! There, there! Theeeeere! Goood! Whew! Aah! Good, good, aaaaaaaaaah! Not yet! Until now it was I that men called an octopus! An octopus! Ooh! Whew! How are you able…!? Ooh! yoyoyooh, saa… hicha hicha gucha gucha, yuchyuu chyu guzu guzu suu suuu….[1]

While perhaps lacking the delicacy of the images, the text speaks to a celebration of the pleasures of sex, without the presence of moralizing or condemnation. Many shunga are scenes of mutual (or group) pleasure. While many of these images were produced by and for men, and often present the female body for a voyeuristic male gaze, many other examples are intended for a straight female audience. The genre of shunga as a whole seems to celebrate sex in the fullest range possible, featuring solitary figures masturbating (sometimes while gazing upon shunga prints, within the prints), straight couples, gay and lesbian couples, interspecies couples, groups, and on.

Not all shunga were produced with the level of care and nuance of those of Hokusai, but many were, even some that are if anything more overtly graphic. These works by Hokusai – a major Japanese artist working 200 years ago – should serve to establish that sexual imagery, even openly erotic and explicit imagery, despite common assumptions, is neither a modern nor a Western phenomenon, nor is it a marginal theme in the history of art. The section that follows examines prehistoric images about sex, ancient Greek and Roman erotic imagery, and Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres’ nineteenth-century French scenes of Turkish harems.

Comparisons and Connections I

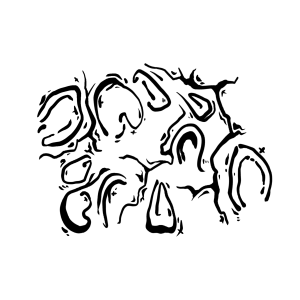

The representation of sexual activity is as old as representation itself. Paleolithic cave paintings feature many images of animals, as discussed in the Nature chapter, but also contain many human figures, as well as human-animal hybrids creatures. Images of women that emphasize their reproductive capacities are well-known and frequently reproduced. Images of sex and of disembodied genitals are less frequently reproduced but also more common. Hundreds of examples survive, the majority of which depict female figures and body parts. Many of these focus on the reproductive organs, to the exclusion of any other features. Some focus on the torso or lower abdomen, with the pubic triangle enlarged in scale, indicating its centrality to the image. Others eliminate all other features, whatsoever, presenting disembodied vulvas of various shapes.[2]

Do they celebrate female fertility, or male lust, matriarchal power or female subjugation? We cannot be certain about the meaning(s) or intent behind these images since, as prehistoric images, there are no texts to supply explanations, and few contextual clues regarding these simple, line-drawn images. However, as the hundreds of known examples of vulva drawings are also echoed in a range of other media including stone and ivory carving and clay sculpture, their importance cannot be overlooked. Indeed, there are even fossilized shells that were likely transported great distances in order to be collected by prehistoric peoples apparently because of their strong resemblance to the shape of human vulvas.[3] Whatever purpose these images served, whatever goals their creators had, they clearly constidered this disembodied form to be of great significance.

Often representations of sex in art focus on reproduction, but to do so to the exclusion of its other functions is to mischaracterize the role that sexuality plays in human society. In addition to allowing Homo sapiens to carry on as a species, sex is used to define relationships, express love and intimacy, to establish hierarchies of power, and, of course, to provide pleasure. In order to talk at length about sexual imagery, it is necessary to discuss “the gaze.” This is a term used in art history and related fields to describe a sexually charged form of looking, and it generally implies uneven power relations, frequently connected not only to gender but also to notions of race and “exoticism.” Most often, it is used to describe the lustful look of a (usually clothed) man at a (usually naked) woman. The term can be used to describe looks among figures within works of art, but more often is used to describe the look of the viewer outside of the work at the figures within it.

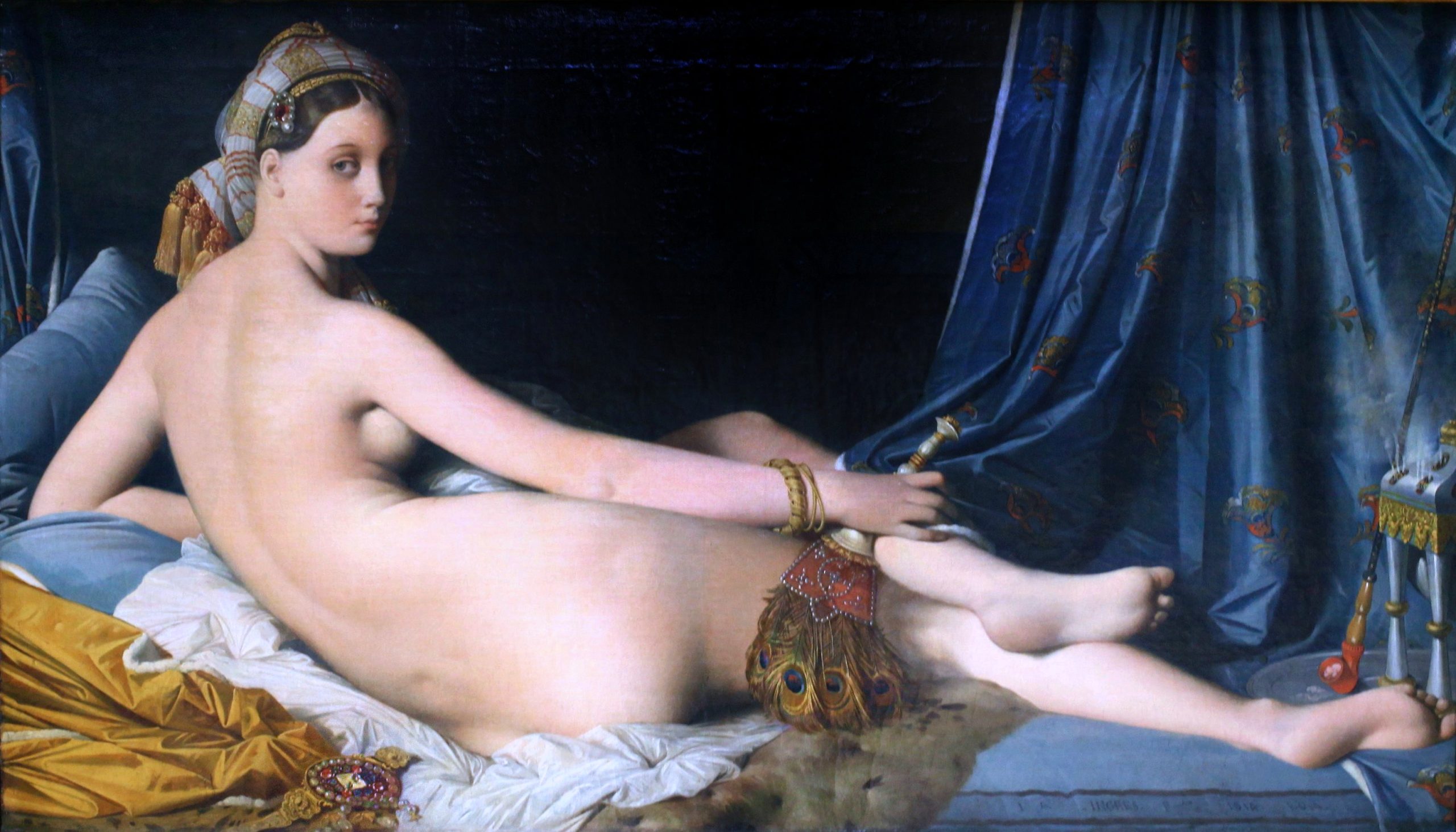

Few artists are more obvious in their construction of the male gaze than Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, whose Napoleon on his Imperial Throne (1806, see the Power chapter) showcases his strong interest in representations of power. The issue of power might seem less central to his The Grand Odalisque (1814), but through the concept of the gaze we can see the intersection of the themes of power and sex. The image is richly sensual, exhibiting Ingres’ virtuosity as a painter of surfaces and textures. The contrasts among the representations of the crumpled sheets, soft fur and feathers, hard jewels and, most importantly, smooth, soft skin of the woman invite us into the work. The contrast in color tones – the cool blues of the setting, and the warm peaches and pinks of the woman – emphasize the potential warmth of her body. The pose of the figure, whose back is toward us, but who turns to look over her shoulder at us, is gently sinuous. Ingres has elongated the figure’s back, encouraging our eyes to caress her body slowly.

An odalisque is a woman enslaved or serving as a concubine, especially in a Turkish or Ottoman harem. The opium pipe at her feet, her head wrap, and other small touches throughout, serve to establish the setting of the work. In the nineteenth century, when the work was painted, Turkey was the site of considerable European fantasy, in which it was seen as a land of moral decadence, of languid, opium-fueled sensuality and sexual license. In essence, the “Orient” – the term used at the time to describe the Near East and Middle East, as well as South and East Asia and even some of North Africa, symbolized all that European society of the day denied itself.

This painting was so central to Ingres’s career that he painted many simpler reproductions, often in black-and-white, from 1814, when he produced the original painting, and the 1860s. If an artist repeats an image for almost half a century, it is certainly a key image in their career.

An 1854 photograph by J.-A. Moulin based on The Grande Odalisque removes some of the pretext of its prototype. The photograph is a loosely faithful re-staging of the painting, with the parted curtains suggesting that the nude woman is being revealed to us as she reclines, with her back to us but her gaze, over her shoulder, perhaps meeting ours. However, unlike Ingres’ spotless odalisque, the photographic model has dirty feet, perhaps grimy from the photography studio floor. This detail breaks the fantasy that of looking at an “exotic” member of a pampered and secluded harem far, far from Europe, and remind us that this model is actually a lower-class French woman merely posing as such. Stripped of the illusion provided by the setting, the photograph is perhaps closer to straightforward pornography in a way that the more explicit but also more complex imagery of Hokusai is not. This is not to say that if her feet were clean this would be “art,” but since they are dirty, it is “pornography.” Rather, the dirt on her feet reveals to us the sordid circumstances of the production of the photograph and highlights the gap between what the image attempts to portray – a Turkish odalisque – and the reality behind it. It also reminds us that the model for Ingres’s painting was also not an actual odalisque, but also most likely a lower-class French woman.

Who are we, when we look at Ingres’ large, nearly life-sized painting? The artist places – indeed, attempts to force – us into the position of the sultan, contemplating this woman who is kept for his sexual pleasure. This is the embodiment of the sexually powerful male gaze. It is worth noting that a female viewer, when looking at this painting, is placed in the “male role” of the empowered viewer, just as surely as a male viewer, that a gay male viewer is pushed into the position of a straight male viewer, and so on. One more Ingres painting, though, should clarify these issues yet further.

His The Turkish Bath (1862) evokes the same exotic orientalist fantasy – that is, the European fantasy of the “exotic Orient” – as also see in The Grand Odalisque (though it is curious that one of two versions of The Turkish Bath was owned by the Turkish-Egyptian collector Khalil Bey, who had an actual harem).

There are three fundamental differences between the The Grand Odalisque and The Turkish Bath. First, in place of a single odalisque, we see the entire harem. The women, predominantly naked, lounge indolently upon one another while they smoke opium, play music, eat, drink, and caress one another. The image is almost exclusively composed of the organic, curvilinear lines that define the soft bodies of the female figures, echoed by the round format of the image. Second, none of the figures looks back at the viewer. Third, the horizon line is set curiously high, above the horizontal center of the image, which makes the viewer’s eye-level unusually low, as if we are crouching down to waist-height while we look at the scene. Coupled with the tondo format – the circular canvas – the effect is that of peering through a keyhole at the harem, observing the naked women without concern of being, ourselves, observed. This allows a viewer to gaze freely, slowly, perhaps longingly, upon these women without having to confront their gaze, and therefore their individuality and humanity.

The painting, then, gives the vantage point of the voyeur, of the Peeping Tom, intended to allow a wealthy European, clothed, straight male audience to ogle enslaved, naked Turkish and African women in complete comfort and with a sense of mastery and control. These paintings are often celebrated for their beauty, and for the technical skill of the artist, but we should not do so without remaining aware that they encapsulate the colonial, sexist gaze of the orientalist.

Turning from a European work depicting a European fantasy of “the East” to a work produced in the Safavid Empire (Persia/Iran), we find a very different approach to the representation of eroticism. This Persian miniature by the prominent artist Muhammad Qasim Musavvir depicts Shah Abbas I, a Persian shah (king) celebrated for his military victories, but rather than showing a scene of battle and conquest, the artist depicts the ruler relaxing beneath a tree, while a serving boy offers him a cup of wine.

The figures are richly clothed, including with highlights in gold. The image reflects reports of Abbas’ love of wine and feasting, and also of youthful male cup-bearers and pages. Rather than opting for the graphic nature of shunga, or the attempt to generate a personal connection with the viewer found in Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque, this image seems elegant, allusive, and self-contained.

The figures are in close contact with one another, as the older and more powerful figure pulls the young figure toward him. The turban signals that the young figure is male, but he is marked according to Persian culture of the period as effeminate, with his soft, smooth jawline and long curls. The phallic wine jug between his legs, which he grips and points toward Abbas’ groin, alludes to their sexual relationship. At the right edge of the image is a short poem in Persian that reads:

Him! May the world bring you satisfaction of three lips: the lip of your lover, the lip of the stream, and the lip of the wine cup.[4]

Such homoeroticism is common in Persian art and, especially, literature, where male beauty is often characterized as a powerful force, having a highly distracting effect on other men. In this way, the power of the gaze is reversed, so that it is the gazer who is disempowered, even incapacitated by his attraction to another.

While many cultures partake of the problematic gendered gaze epitomized by Ingres, others contain more balanced or varied representations of sexuality. Sexual imagery is absolutely central to the art of ancient Greece and Rome, where we find images that run the gambit from richly sensual to crudely humorous, and focused at least as often on the beauty or allure of men as of women. A series of works will serve to establish a few of the roles of sexual images in the period: two figural sculptures and two wine cups.

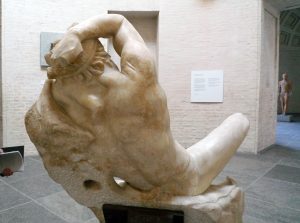

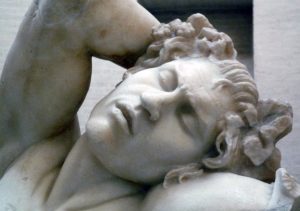

A great many images of the goddess of carnal love, Aphrodite (know to the Romans as Venus), survive, and many of these smolder with passion and energy. We will look, though, at other figures treated as the subjects of an erotic gaze. The Barberini Faun is a strongly emotional work believed to have been made in the Hellenistic Period, a period in ancient Greece beginning with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and ending in 31 BCE, when the last Hellenistic Greek dynasty was conquered by the Romans. The surviving work might actually be a Roman copy of a Hellenistic Greek sculpture (or possibly even a Roman invention), but in any case, it is quite typical of Hellenistic works in that it does not seem to be self-contained; instead, it solicits an emotional response from the viewer.

The image depicts a sleeping figure that at first seems to be a human man, but on close examination is revealed to be a faun or satyr, a mythical creature that is half-human, half-goat. Though fauns are usually depicted as goats from the waist, down, here the only clearly identifying features are the tail that can be seen emerging from the base of his spine and the horns, now damaged and easily missed amongst in his tussled hair and wreath of grape vines.

As semi-human beings, fauns were associated with animalistic sexual passions, and were depicted in all manners of sexual activity with a wide range of sexual partners, male and female, human and animal. This figure exudes sexual tension. The pose of abandon, with the legs splayed apart to reveal the figure’s genitals, recalls the unselfconscious pose of an animal as much as of a human. The figure’s loose pose presses out into our space and invites us to circle the statue. The tightening of the figure’s abdomen indicates that his sleep is not relaxed and peaceful, but rather, torrid and intense. The sculptor seems to have captured a moment in time with such precision that we can tell that the faun has just inhaled, and is momentarily holding his breath before exhaling.

The faun’s turbulent sleep is also emphasized by his facial expression. His head is tipped back, with eyes closed, brows furrowed, and lips parted, in a manner that recalls the pose of the woman in Hokusai’s Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife. He seems to be in the midst of an erotic dream, and since he is insensible – possibly even in a drunken stupor resulting from partying with the god of wine, Dionysus – his muscular body is presented for the viewer’s gaze much as the bodies of Ingres’ odalisques are.

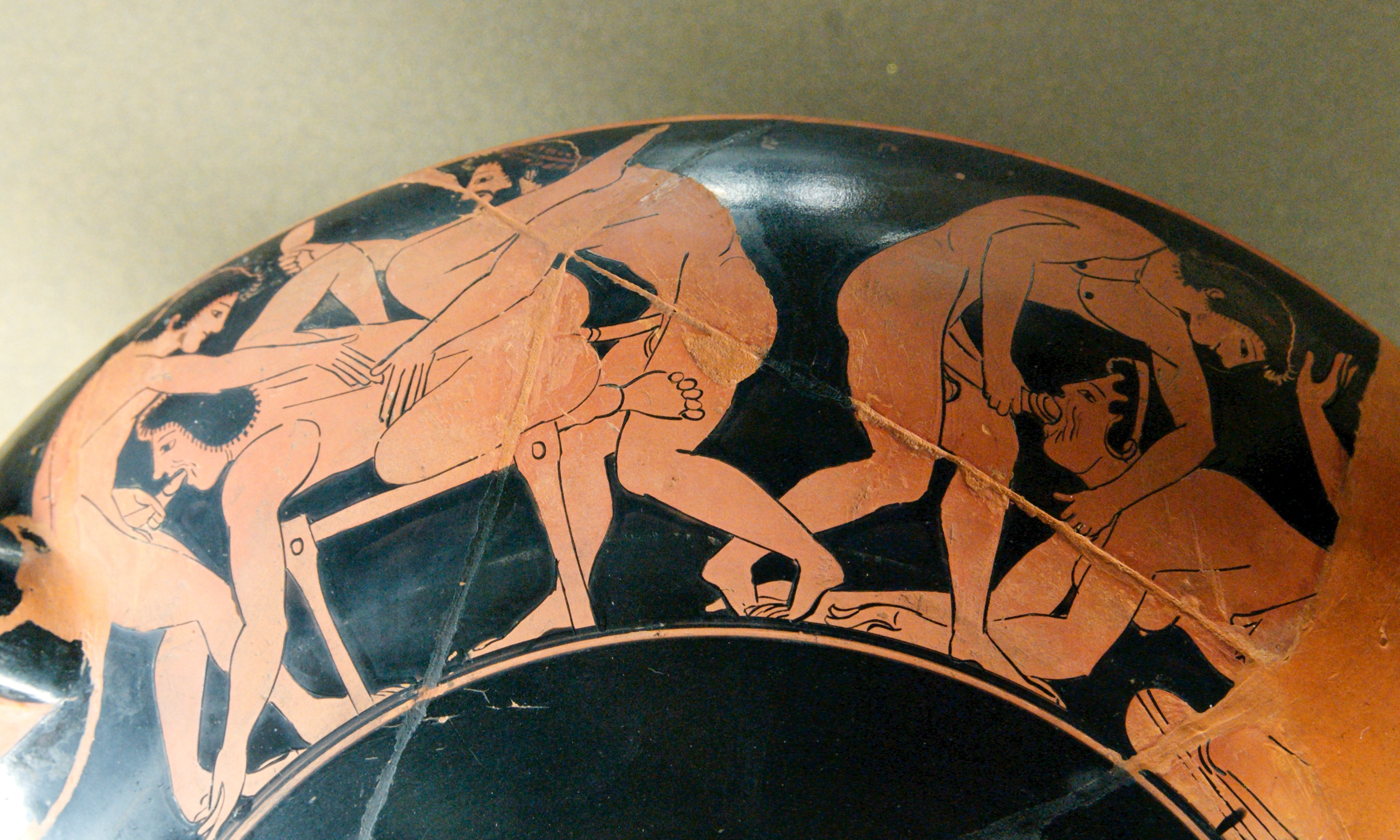

The delicacy of representation we see in the Barberini Faun is uncommon. We have many more examples of sexual imagery preserved in smaller, less costly artifacts. In particular, such imagery was a frequent choice for kylixes – large, shallow wine cups, often used at symposia, which were ancient drinking parties that often culminated in sex. One red-figure kylix from ca. 510 BCE, for example, depicts a wild orgy in which many revelers have sex with one another, in pairs and in groups. The execution is somewhat rough, with limited expressions on the figures (though the one at the left edge of the image seems to smirk).

In this detail, we see two groups of three, linked by the overlapping of feet and hands in the space between the groups. The figure in the middle of the rightward trio is clearly female, though the sex of the figure in the middle of the leftward trio is indeterminate. The hairstyle suggests a male figure, but since the figure’s back is to us, we cannot be certain. The lines of the image are crisp and energetic, and though they might seem as if quickly painted, the careful overlaps connecting figures within and between the trios suggest attention to detail.

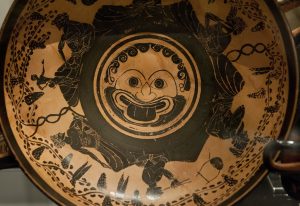

An image of a contemporary black-figure kylix gives a better sense of the shape of these wine cups. The scenes on the outside of the cups would not be easily visible until the wine within was nearly consumed and the cup tipped back steeply. The imagery here makes a sort of joke about the effects of wine on such a drinker. Holding the large cup by the two handles at the sides, and draining the last of its contents, the drinker would in essence be holding a mask up before his face. The two large, staring eyes visible on the underside would cover his eyes and the handles would mimic wide ears. The cup foot – the flared circular form at the base – becomes a pig’s snout, so the drunk reveler is reduced by wine to a goggle-eyed beast. At this point, drinker and their companions might well be preparing to engage in just the sort of activities the orgy image presents.

The Bomford Cup (525-500 BCE) also playfully implies the effects of wine on such a drinker. The eyes and ears are more or less the same as the previous example, but in place of the more usual circular cup foot, the potter has sculpted a set of male genitals. The inside of the cup contains a delicate and beautiful scene of partygoers reclining in flowing robes, their heads crowned with wreaths and their room hung with grapevines. As the cup is emptied, and the underside revealed, the drinker is transformed into a caricature of sexual excitement, reduced to his genitals, to his arousal. Between the eyes on the cup is the face of a faun, reinforcing the sexual energy of the work.

The final Ancient work to be considered here is a delicately rendered sleeping figure, probably a second-century Roman copy of a Hellenistic Greek original. As with the Barberini Faun, the work implores an emotional response. In the first image, we see the individual from the side that was likely intended as the initial view.

From this angle, we see the soft flesh of the figure’s back, rendered with such delicacy that it seems as if it would yield to a gentle touch. The figure, like the faun, is sleeping restlessly (here, upon a stone cushion produced for it by the Italian Baroque master, Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the seventeenth century, after its rediscovery). The face is turned toward us, but the torso then twists away, and so it is difficult to speak of the sculpture’s “front” or “back.” Instead, the torsion of the human form encourages us to walk around the sculpture. As we work our way down the figure’s body, we see the lower legs and feet are tangled in the sheets; the sleeper has been tossing and turning, and one foot is raised, toes curling tensely upward. This is a very complex pose, gracefully achieved.

Circling the sculpture, we see the figure from a range of angles, ultimately arriving at the opposite side from where we began. The intent is clearly to surprise the (straight male) viewer: from the original view, the figure seems to be a sleeping woman. We see a feminine face, long, tousled hair, a narrow waist, soft and broader hips, and the swelling of a breast. Having circled the sculpture, though, we see that the figure bears male genitals. According to a Greek myth, Hermaphroditos was the son of two deities, Hermes and Aphrodite. The nymph Salmacis fell in love with him and, when he refused her, begged the gods to never be separated from him. Zeus granted her wish, merging her body with his and producing a figure that was lauded in the Greek period as an ideal form, unifying male and female into a single body.

This figure is complicated, and needs to be considered with great care. It is sometimes seen as a sort of joke, tricking a presumably straight male viewer into a state of arousal only to surprise him with the revelation of male genitals that would frustrate his lust for the figure he assumed was female. However, this theory overlooks the stunning workmanship of this delicate marble sculpture, rather extravagant for a simple visual punch-line. More importantly, though, the “joke” theory ignores ancient notions regarding what constitutes acceptable and “normal” sexual behaviors. The notion that this is some sort of a joke relies on a problematic modern notion that same-sex attractions are to be ridiculed, and therefore that a person “tricked” into feeling them has been embarrassed. Such notions are largely absent in Greek art and literature. Ancient viewers were more likely to have seen in the figure an evocation of the earliest humans – believed by some Greeks to have had both sexes joined into dual-beings – or of the presence of the masculine and feminine elements that exist in all people.

Finally, the sculptor has also granted the figure a sense of interiority. That is, though this is actually just a piece of stone, when we look at the work, we cannot help but imagine what this sleeping figure might be dreaming of, as if it were a real, living person. In this sense, it is much like the Barbarini Faun. Both are powerful works that engage with the viewer, that pull us in, induce us to circle around them, and most importantly, to puzzle over what such beings would think about, dream about, and perhaps long for. In this, both works are more than mere objects for the viewer’s gaze. None of this fits with the theory that this riveting figure is nothing but a cruel joke — indeed, a doubly cruel one, embarrassing the viewer at the expense not only of this complex sculpted figure, but also through the dehumanization and denigration of living people whose bodies are not located at either pole of the spectrum of sex and gender. The sleeping figure is no mere joke. Instead the work is a sensitive image of a figure neither male nor female, but graceful, sensuous, and full of provocative ambiguities.

SPOTLIGHT IMAGE II:

KANDARIYA MAHADEO TEMPLE, KHAJURAHO, MADHYA PRADESH STATE, INDIA (1025-1050)

VIEWING QUESTIONS

- How do the artists create a sense of movement?

- How do the forms interrelate with one another?

- What is the effect of the repetition throughout the temple?

- How do variety and unity play out in the temple’s imagery?

SACRED EROTICISM

The Kandariya Mahadeo Temple, Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh State, India (1025-1050) is a remarkable work, a massive sandstone structure covered in several hundred carved figures that ripple across its undulant walls. It is a Hindu temple, primarily dedicated to the god Shiva, one of the most important of the thousands of Hindu deities. The temple houses a linga – a cylindrical column that is a symbol of Shiva and, according to some scholars, a phallic symbol – beneath its highest peaked roof. From a distance, the intricate decoration is reduced to a busy pattern, but as we approach the structure, we can discern hundreds of idealized figures, many of them erotic in nature. The highly sexual figures are integral to the temple’s conception and design, and essential to its function.

VISUAL ELEMENTS

The Kandariya Mahadeo Temple is an overwhelming mass of stone, of undulating and cascading forms. The towering roofs mimic the peaks of a mountain range, rising successively from the entrance porch at the east to the rearmost chamber at the west. The whole structure sits atop a massive, solid “basement” level, articulated with a series of horizontal bands of molding, regularly punctuated with niches containing relief sculptures. The imagery, though, is largely concentrated in the three main registers of sculptures at the main level, running between the open porches and containing a line of 650 sensuously idealized figures, human and divine, sculpted at approximately half life-size.

One set of images from among the vast profusion of lively figures surrounding the temple is the focus of this section. The scenes are at once lively and orderly, projecting and receding but in a clear and regular pattern. Similarly, the figures are consistent, yet varied. In each band, we see a sexual scene at the center, with a pair engaged in coitus, flanked by two auxiliary figures. These central scenes are surrounded by pairs of female figures, in turn surrounded by pairs of four-armed deities, surrounded by women (perhaps yakshis). The richly bejeweled deities sway in gentle contrapposto, and look straight out at us. They hold their four hands (some of which have broken off) in similar positions and carry similar items, but a close look reveals differences. Some have animals at their feet, while others have human figures. One is bearded. Their headdresses are individualized, but many of the figures – male and female – seem to have the same features: wide, narrow eyes, overarched with thin, sharp eyebrows; broad noses; prominent, bow-shaped lips. The result is a unified composition that is nonetheless consistently interesting. Too little unity and the temple would be chaotic. Too much, and there would be no incentive to examine more than a few of the hundreds of figures.

Unlike the figures of four-armed deities, the female figures generally do not look out at us. Instead, they seem to comport themselves for the viewer’s pleasure. Draped with elaborate jewelry and crowned with a great variety of headdresses and diadems, these lithe figures twist and turn in complex poses possibly drawn from yoga practices common in the period. Some face outward, displaying and even fondling their full breasts. Others turn their backs to us, posing in exaggerated contrapposto, thrusting their hips in our general direction, as if openly inviting our gaze. The motion of the figures echoes (and is echoed by) the very form of the building, with its many protrusions and recesses.

The forms are, like much sensual or erotic imagery, predominately curvilinear. Here, though, this is counterbalanced and therefore emphasized by the sharp-edged rectilinear soffits on which the figures stand, and the rectangular frames around the smaller figures and floral patterning between the bands. These squared elements highlight the loose, swaying, curving, organic nature of the figures, and their diaphanous drapery.

The lower band of figures, here, contains the most acrobatic of the lovemaking couples visible in the detail. The woman stands with her legs spread wide apart, helped by the two voluptuous women at her sides. The man stands unsupported upon his head, with his legs bent as if to hold onto his partner for support. Rather than using his hands for balance, he reaches up to place them on the flanking women’s groins. These figures are scantly clad, even in the context of this temple’s sculptural program, wearing only a few necklaces, armbands and other such accessories, which serve not to clothe them but to emphasize their nakedness.

The emotive power of the work is not contained merely in the moment – mostly hidden from view – where their sexual organs meet, but in the numerous gentle gestures of touch, and in the gazes exchanged by the figures within the scene. The quartet is sculpted with great inventiveness, carved with such delicacy and grace, so that what otherwise might otherwise be an amusing scene – given the gymnastic complexity of the group – becomes touching and beautiful.

In another panel, the two central figures are so complexly intertwined that at first it is difficult to determine whose legs are whose. The two legs that stand upon the ground are similarly posed and aligned. Likewise, two legs are raised and curved around the couple’s waists. However, a careful inspection – and these sensuous and richly carved works do invite such close looking – reveals that each figure is standing on one leg while they each wrap their other legs around their partner. Serenaded by small musicians in the band above them, the figures gaze deeply into each other’s eyes. She tugs on his hair, pulling his lips to hers, while he presses her back and grasps her thigh, holding her body against his. The two seem a completely self-contained unit, unaware of the torrent of figures around them, even oblivious to the man and woman on either side of them who masturbate, presumably inspired by their torrid passion.

Crouching beneath the legs of the man to the left is a small female figure who is nonetheless clearly an adult, based on her voluptuous form. We do not know who she is, though she is represented in hieratic scale, and so must be a figure of lesser importance. Her gaze, though, serves to point our eyes right to the sight of the couple’s union, and her smile may serve to suggest the desired response from the viewer.

Deep within the sanctuary at the heart of this complex structure is the linga or lingam, a cylindrical column obscurely symbolic of Shiva. This simple, unadorned form stands upright on an elaborate base in a niche, surrounded by waves of voluptuous female figures. The role and symbolism of the linga is debated within Hinduism, but it the form is likely to have begun as a phallic symbol – a stand-in for a penis – and therefore as an emblem of fertility and power. Some are more overtly phallic in shape than the example at the Kandariya Mahadeo Temple. However, the linga does not represent human sexuality – though it seems to derive from it. Instead, it evokes the cosmic powers that Hindus brought the universe into being.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

The Kandariya Mahadeo Temple is in the Nagara style, prevalent in northern India in the medieval period. These structures frequently feature erotic sculptural imagery on their exteriors. While this example is among the most celebrated, it is also quite typical of the imagery of the style. The temple may have been commissioned by Vidyadhara (ruled 1004-35), one of the powerful Chandella rulers who collectively were responsible for building approximately fifty temples in Khajuraho around the turn of the first millennium. This group is characterized by highly complex forms for the temples, as well as by the imagery adorning them. They bear many horizontal bands of decoration, as well as many protrusions and niches, which create restlessly active structures.

The imagery was puzzling to its first European audiences, since the majority of these viewers were Christians, unused to celebratory sexual imagery in religious contexts. Hinduism, though, views sexuality as a positive aspect of human identity, connected to fertility and reproduction, but also to spiritual attainment. The Shilpa Prakasha (Light on Art), a text for architects and sculptors contemporary with the Kandariya Mahadeo Temple declares that images of attractive women, for example, are not merely acceptable but outright necessary for a successful monument:

As a house without a wife, as frolic without a woman, so without the figure of a woman the monument will be of inferior quality and will bear no fruit.[5]

Indeed, the temples of Khajuraho frequently feature the sixteen female figure types recommended by The Shilpa Prakasha.

There are several arguments advanced in explanation of the remarkable array of erotic images gracing Hindu temple walls. They may be intended to imply (or invoke) fertility and abundance. Alternately, they may be metaphorical representations of a mystical union celebrated in the Upanishads – sacred Hindu spiritual texts. According to the doctrine of monism followed by some Hindu groups, the atman – the eternal self within an individual, somewhat like a soul – was part of Brahman – the infinite and unbounded power that sustains the universe. Monism teaches that individuals are one with Brahman, originating within it, connected to it throughout life, and returning to it after death. This union of two seemingly distinct entities was represented through the merging together of a couple in sexual union. A passage from Brihadaranyaka Upanishad reads:

In the embrace of his beloved, a man forgets the whole world – everything both within and without; in the very same way, he who embraces the Self knows neither within nor without.[6]

It is also possible that the images relate to the contemporary prominence of the Kaulas, a tantric sect that worshipped Shiva and held sexual intercourse as central to their religious practice. Final interpretations are difficult, since Hinduism is not a single, doctrinal belief system. It grew out of earlier traditions of the Indus Valley in modern-day Pakistan, and was not based on the teachings of a single individual, or on a single text. There is not even a single interpretation of the divine. Indeed, Hinduism might be considered to be a loosely connected group of hundreds or even thousands of religions, based on hundreds of thousands of deities, though these are also often seen as avatars or manifestations of the formless, boundless Brahman.

These complicated, passionate images certainly celebrate the human form, and the power of sexuality. The specifics of their connections to religious beliefs and philosophical principles are less certain – or perhaps varied and open. The following section considers works from Italy, Germany, Peru, Cochiti Pueblo, and France, some of which celebrate human sexuality in its remarkable diversity, and others that condemn it. They are rooted in tradition, and at times groundbreaking; they draw on religious beliefs and cultural practices. While the specific messages vary, they continue to demonstrate the centrality of human sexuality to the visual arts.

Comparisons and Connections II

The profusion, exuberance and variety of erotic imagery in Hindu temples is perhaps unfamiliar to those only schooled in the European canon, but many religions make use of sexual imagery, either celebrating or condemning it, based on the narrative of the religion. Christianity’s traditional perspective on human sexuality – which was central to the religion’s art and rhetoric in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and continues to have a significant influence on the lives of Christians and others living in Christian-majority cultures – is rooted in the Bible’s account of the Fall of Man. According to the text of the Book of Genesis, the monotheistic God common to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam creates the first couple, Adam and Eve, and provides them the beautiful and bountiful Garden of Eden in which to live, but instructs them that they must not eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Prior to eating the fruit, they are unaware that they are naked, which is often interpreted as a sign that they did not yet have any sexual consciousness, any sexuality. After disobeying God’s order, they become aware that they are naked, notice the differences between their bodies, and cover their genitals out of shame.

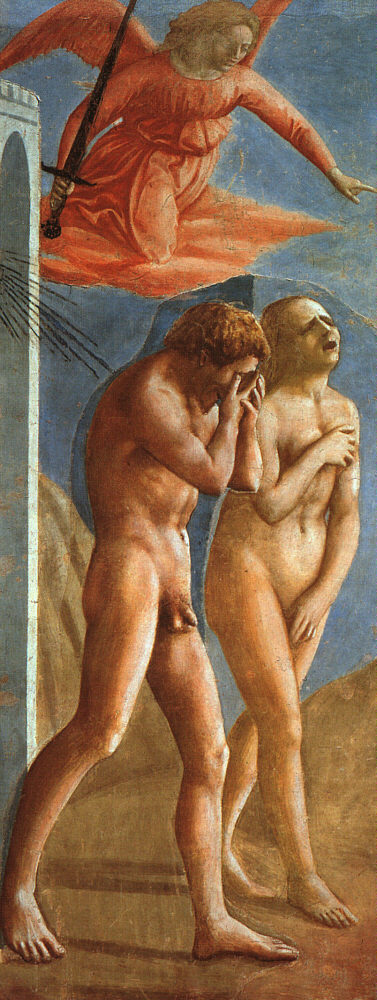

Many artists have represented this subject over the last two millennia, and we will examine three examples. The first, by Tomasso Guidi (also known as Masaccio), is a fresco – pigment mixed into wet plaster and painted on a prepared wall surface so that, when the plaster dries, the painting is not merely on the wall; it is the wall. His work in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence (ca. 1427) shows the Expulsion of Adam and Eve, the moment in which the primordial couple are thrown out of Eden after their disobedience.

In sharp contrast with the numerous joyous figures adorning the Kandariya Mahadeo Temple, these progenitors of humanity are agonized by their sorrow, guilt, and regret. At the very left of this image stands the gate to Eden. Sharp, straight black lines – once gilded – radiate outward, representing the angry voice of God. Adam, covering his face, seems to hunch away from them as they stab out toward his back. The angel (or cherubim) glares down at them from above, while pointing vigorously away from Eden. The text of Genesis reads:

After he drove the man out, he placed on the east side of the Garden of Eden cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life.[7]

Adam and Eve are cast out into the harsh world. Represented in smooth, dull shades of tan, it seems dry and lacking in any fertility or vegetation. These early moments in religious narrative foster a negative relationship with sex, sexuality, and reproduction, which early Christians saw as sinful. Indeed, some of the most prominent early Christian theologians argued that the devout should abstain for all sexual contact whatsoever, even in the context of marriage for procreation.

Masaccio’s image conveys a sense of shame and humiliation connected with sexuality. Unlike the proud figures on the Kandariya Mahadeo Temple, Eve covers her breasts and genitals. This early Renaissance painting demonstrates the period’s interest in naturalistic representations of the human body, but Masaccio uses this naturalism as a vehicle to convey the figures’ shame. Adam’s torso is fairly similar to that of the Barberini Faun, but where the contraction of the faun’s abdominal muscles is used to convey a sensuality or eroticism, Masaccio uses the same device to indicate that Adam is wracked with sobs.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, the central figure of the Italian Renaissance and one of the most prominent artists in world history, spent time in the Brancacci Chapel, drawing sketches of Masaccio’s innovative figures when he was a young artist. His image of the Fall in the Sistine Chapel (1508–1512) is clearly based on Masaccio’s, but Michelangelo provides more of the narrative. To the left, Adam and Eve reach for the forbidden fruit, handed to Eve by the serpent, whose body turns into that of a woman. To the right, they are cast out in poses drawn with some variation from Masaccio’s figures, again awash in shame, horror and revulsion.

From before the Fall to after, Eve transforms. Before eating the fruit, she is beautiful, youthful, and radiant, appearing calm and confident; after, she is haggard, older, and darker (which, according to racist beauty standards in Europe in the period, would be read as uglier than her pale pre-Fall coloring). In medieval and Renaissance Christianity, which held that God designed everything in the world as a teaching device, inner and outer states were thought to match one another. Therefore, as Eve falls from purity to impurity, her outer form is made to match her corrupt inner state.

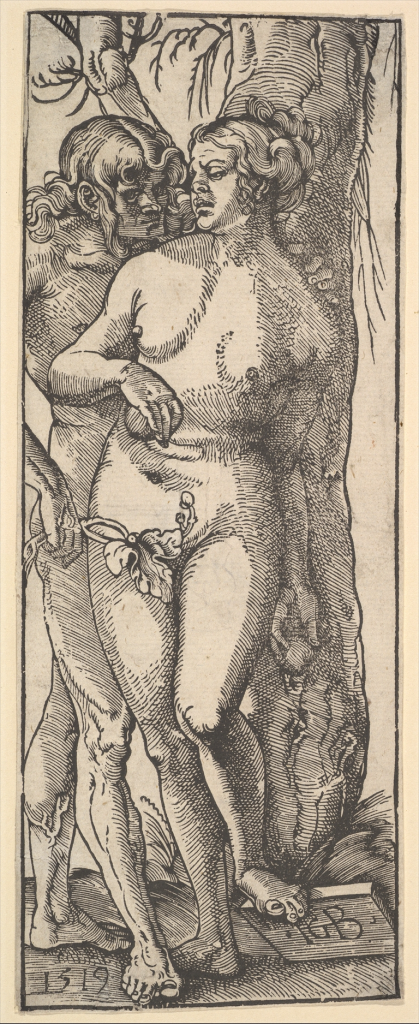

If these two Italian images gloss over the actual role of sex and sexuality in the Fall (perhaps implied by the proximity of Eve’s face to Adam’s genitals in Michelangelo’s image), German Renaissance artist Hans Baldung renders this central to his images of the Fall, including a woodcut from 1519. Baldung dedicated much of his work to the exploration of sexuality and sensuality, returning to the theme again and again, frequently with a misogynistic tone. In comparison to the works by Masaccio and Michelangelo, his woodcut is a smoldering scene of sexual tension.

This sort of woodcut, unlike Japanese Ukiyo-e, produces only monochromatic images, but Baldung subverts their stark quality by using hatching and cross-hatching to give the scene the illusion of shades of grey. The dark tree and Adam’s shadowed body frame, contrast with, and emphasize the brighter, centered nude body of Eve, posed in contrapposto like a classical statue of Aphrodite.

Adam looms over Eve, placing a hand perhaps possessively on her shoulder. She turns as if startled. Her expression is ambiguous: Is she repulsed, aroused, or, perhaps, both? Her left hand is lowered as if absent-mindedly dropping the very fruit that was the cause of their interaction. Adam holds a conveniently posed fig-leaf, concealing Eve’s genitalia from view, and yet its form seems mildly phallic, with the central lobe of the suggestively-shaped leaf pointing directly toward her hidden vulva and drawing our eye to the darkened space between her thighs. Additional shoots of the branch arch lewdly upward.

If this image might suggest ambiguity regarding Baldung’s interpretation of the role of sexuality, his closely related painting of Death and the Maiden (ca. 1520-1525) should clarify his perspective. The figures are a mirror image of those in his Fall of Man, but Baldung has replaced the glowering figure of Adam with a rotting corpse, a personification of Death. If Eve’s expression was ambiguous in the print, the maiden’s horror is palpable in the painting. The implications are clear: for Baldung and many of his contemporaries, sex led to the expulsion from the Garden of Eden and therefore to human mortality, and they saw sex, and the desire for it, as a mortal sin.

The ancient Moche culture, a pre-Incan civilization that flourished on the northern coast of Peru from about 200 BCE to about 600 CE, on the other hand, seems to express a rather permissive view of sex. Their pottery contains images of a range of sexual activities almost as wide as that depicted on Hindu temples, along with other scenes from daily life, animals, plants, and the like, often with humor. They used pots for ceremonies and buried them with their dead, but other uses have been suggested, as well.

The wide variety of sexual scenes has led some to suggest that these pots might have been used for sexual education. Some examples make this seem fairly plausible, particularly those representing heterosexual intercourse, pregnancy, and childbirth. Others, though, would be hard to explain as educational. Humor seems to be the main motivation behind an example depicting an anthropomorphic penis. The penis rises out of the body of the pot, on which the outline of a vulva is drawn, suggesting that the penis is inside a vagina, where it is shown pinching its nose.

Another Moche pot of pronounced inventiveness depicts a seated man, eyes wide, while receiving fallatio from a kneeling woman at his feet. In a similar piece, the woman’s head is a separate piece of pottery, designed to be able to rock back and forth, simulating her activity. It is hard to see how such pots could serve as instructional fertility guides, considering how many of the acts depicted could not lead to reproduction. Instead, they seem to celebrate – and poke fun at – the sheer joy and variety of sexual experience.

Contemporary Native American pottery also explores myriad sexual acts and inclinations. Virgil Ortiz is a Native ceramicist and fashion designer from a family of artists in Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico. As a member of the Pueblo Council, is he a leading figure in his community, and uses his art to bridge the gap between the pueblo and the culture outside of it. He draws on traditional Cochiti pottery techniques, styles and subjects, but also updates these by including very contemporary subjects, transforming the tradition into his own idiom. As Ortiz writes:

So the outside world knows what life is like inside Cochiti, I create traditional figures, but for the Cochiti people I create figures of unknown vocations so the people who rarely leave the pueblo have some sense of what life is like out there.[8]

Cochiti potters began sculpting unusual figures for an export market in the 1870s, and Ortiz continues this longstanding practice, pushing the boundaries further, especially in his two Taboo series. These bodies of work explore themes of drag performance (see links for images of Ortiz’s works), BDSM (bondage and discipline, domination and submission, sadism and masochism), and other subcultures. (For other examples. see here, and here.) As he writes, his goal is to “use Taboo topics to engage people about today’s society, culture, politics, religion and even social media.”[9] The colors – black, beige and dusty red – are the traditional Cochiti pottery colors, and are used to achieve dramatic, high-contrast compositions. The graphic nature of the black patterns on the figure and pot are based on customary Cochiti forms. The forms of his pots are likewise traditional. However, by focusing his imagery on fetishized styles of sexual play and gear common in the BDSM community, Ortiz is able to play with these conventions, updating them and making his work transgressive. As Ortiz writes about one of his pots (image of the other side here):

It’s not the world in which we live our daily lives, but the unseen, underground world where people live out their fantasies that has power. Forbidden desires and fantasies are woven into the leather straps, vinyl and bondage imagery on this jar. Just like the men on the jar preparing to ‘wrestle’, we each wrestle with our human nature. That’s just the nature of the beast.[10]

The traditional triangular patterns on Ortiz’s pots, for example, become more powerfully energized by the danger they seem to pose to the figures between them. The stark, silhouetted forms recall current tattoo styles and fashion designs, and cause his works to resonate with contemporary culture, while evoking Cochiti traditions.

If Ortiz’s pottery representations of sexual subcultures at times render them innocuous, even perhaps cute, the imagery of German photographer and filmmaker Miron Zownir is thoroughly hard-edged, even willfully off-putting. An untitled photograph taken in Hamburg in 1984, for example, shows a man dressed somewhat similarly to Ortiz’s figures, with comparable straps and piercings. Considering that the two works feature the same subject – a person dressed for BDSM – they could not be more dissimilar. Zownir’s tattooed, pierced man stars out at us aggressively. He is defiantly un-idealized, older, a bit flabby and awkward in his straps. Zownir poses the subject slightly off-center, tilted and slouching. His body seems tired and overused, though the tattoo just above his groin – likely intended ironically – reads, “NUR FÜR DICH” [“ONLY FOR YOU”]. This portrait, tame in contrast with much of Zownir’s work, presents a thoroughly unpolished image of sexuality, completely rejecting any sentimentality or romanticism, and instead emphasizing the gritty and harsh nature of some sexual encounters, defying the grace and beauty of works like the Kandariya Temple sculptures or even of the shunga prints. Zownir says that he chooses his subjects based on his own captivation with the bizarre:

I am completely and radically devoted to what fascinates and interests me personally; things that I really want to get into, because they are mysterious to me, uncertain … In this thing, I knew I’d never reach a degree of saturation, when I’d say: now I’ve seen it all. You can never see it all … [V]ery few people dare the approach.[11]

The work of Yayoi Kusama is perhaps more ambiguous in its evocation of sexuality. A Japanese artist who joined the avant-garde art scene of New York City in the 1960s, Kusama practiced obsessive repetition of a few forms, creating art installations and happenings, some of which – in keeping with the ethos of the 60s – she called “nude-ins.” She would cover herself and her often-nude collaborators with polka dots, and they would appear in galleries but also in public spaces, such as her performance at the statue of Alice in Wonderland in Central Park, New York (1968, see here for images).

Kusama appears at the center of the image, fully clothed and shown in the act of painting polka dots onto one of her nude collaborators. Two of the men wear masks of women, while the woman seated on Alice’s lap wears a mask of a man – in this case, Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro, appearing in unclear association with a man wearing a mask of Richard Nixon, who was then running for president. In the context of the oversized figures from the absurdist tales of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, these bizarre figures seem to defy clear assertions of meaning. In her 2011 autobiography, Kusama describes this happening:

How about taking a trip with me out to Central Park… under the magic mushroom of the Alice in Wonderland statue. Alice was the grandmother of the Hippies. When she was low, Alice was the first to take pills to make her high. I, KUSAMA, AM THE MODERN ALICE IN WONDERLAND. Like Alice who went through the looking grass, I, Kusama (I have lived for years in my famous, specially built room entirely covered by mirrors) have opened up a world of fantasy and freedom. You too can join my adventurous dance of life.[12]

Kusama sought out photographers to document her objects and installations. She would appear in these images, often dressed or decorated to appear as part of the work. She would then cut up these photographs in order to produce collages used to advertise her shows. In one such collage, the artist poses on her Accumulation No. 2 (see here for image). nude but for her high-heeled shoes, and covered with her signature polka dots. The “accumulation” work – a couch covered in hundreds of phallic cloth protuberances, which are recurrent elements in her art – was part of her “Sex Obsession” series. In her pose, with her back to us but her face turned back to make eye contact, Kusama is playing with – or perhaps exploiting, or even both at once – her status as the “exotic” Asian object of a Western orientalist gaze in the manner of Ingres’ odalisques, or of standard pinup posters. The photograph of Kusama was taken by Hal Reiff, and then combined with her Infinity Net as a backdrop and a “macaroni carpet” in the background, creating an impossible installation, mixing the scales of the original photographs so that even the tiny macaroni tubes become additional phallic symbols. Naked and surrounded by hundreds of phalluses, Kusama seems to become as much the subject of her advertisements as the works around her.

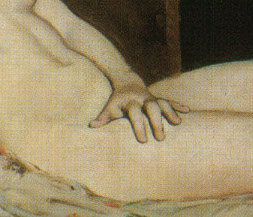

The final image of this chapter is Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World (1866). Like the prehistoric images discussed above, this work strips away any pretense of setting or narrative, focusing our attention directly on the vulva of the figure and, to a lesser extent, on her naked torso and thighs. The power of the image is in large measure the result of the close cropping, so that the figure’s lower legs, arms, and, most importantly, face are cut out of the image. The result is a purely sexualized, objectified image of the woman, dehumanized through the elimination of her face and the reduction of the individual to her role as an object of sexual desire. She becomes permanently available for the gaze of Khalil Bey, the same Turkish-Egyptian diplomat and collector who commissioned one of Ingres’ harem scenes, as well as several other Courbet paintings. Still, the figure’s reproductive potential is conversely elevated as The Origin of the World itself. Bey was rumored to be nearsighted, which puts the intimate scale and cropping of the image into further context, as it is conceivable that the intended viewer would have been quite close to the image while gazing at it. This work, once owned by the famous psychoanalyst and theorist of human sexuality Jacques Lacan – a follower of Sigmund Freud – has been derided as pornographic, condemned as sexist and objectifying, cheered as a proto-feminist celebration of the positive power of female sexuality and reproduction, elevated as libertine, hidden from view, displayed in museum exhibitions, set in its historical context, speculated on regarding its model, traced from owner to owner, and endlessly – indeed, even ironically – reproduced. In its stark presentation, with minimal context, the work resists any simple and straightforward analysis, but like all the images in this chapter, argues vigorously for the importance of human sexuality in the history of art.

CONCLUSION

Sexual imagery has been a part of the visual arts for tens of thousands of years. Such images often strike viewers as particularly compelling and emotionally affective, or especially distasteful, offensive, or even immoral. While some are celebratory and others condemnatory, many are ambiguous, inviting the viewer to contemplate the sexuality of the figures within the works, and therefore to reflect upon their own engagement with sex and the emotions it inspires.

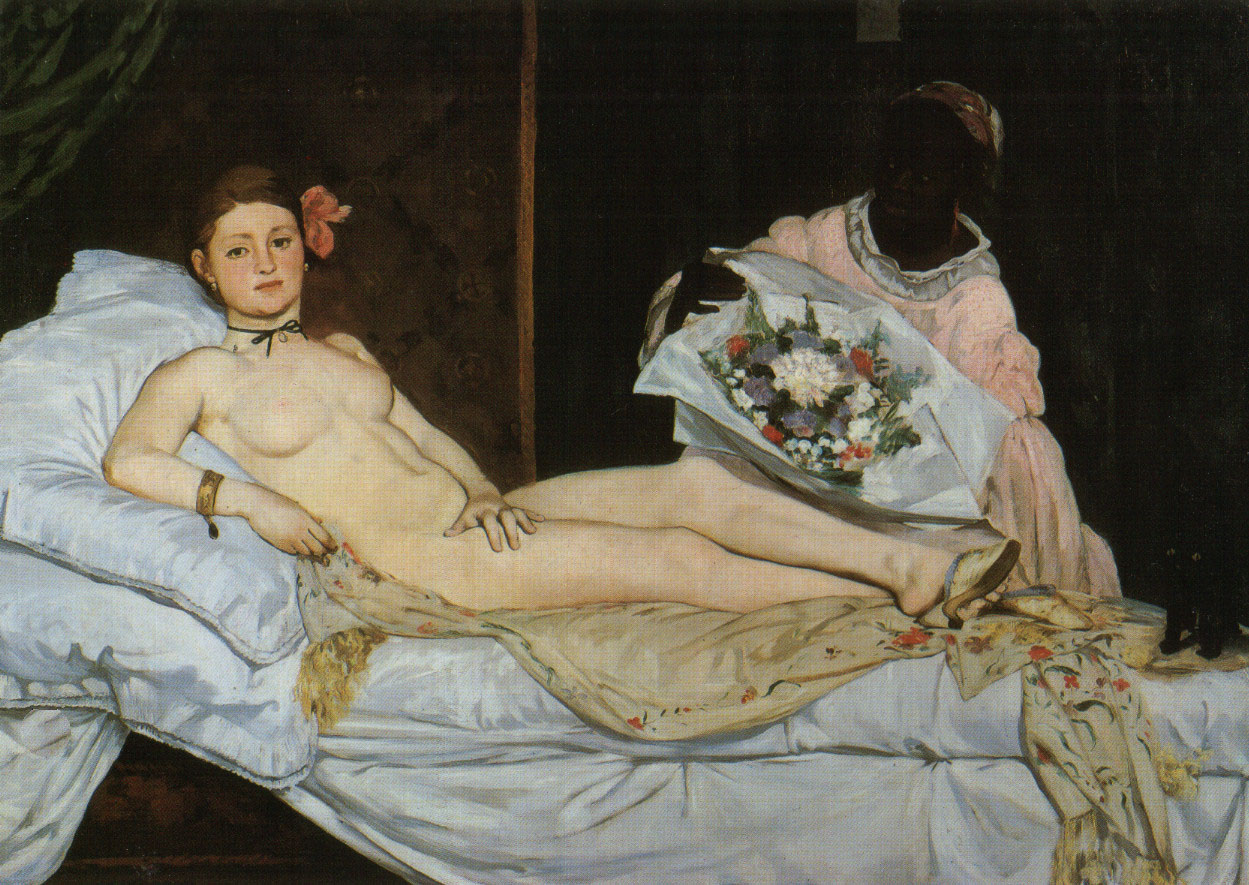

Spotlight Image III:

EDOUARD MANET, OLYMPIA, 1863

VIEWING QUESTIONS

- How does the figure of “Olympia” relate to the viewer?

- How do the colors influence the image?

- What is emphasized, and how?

- How does Manet create a sense of space?

Media Attributions

- Katsushika Hokusai, Untitled, Kinoe no Komatsu (Volume 1), ink and color on paper, ca. 1814. Photo: Public Domain.

- Katsushika Hokusai, Untitled, Kinoe no Komatsu (Volume 3), ink and color on paper, ca. 1814. Photo: Public Domain.

- Detail, Katsushika Hokusai, Untitled, Kinoe no Komatsu (Volume 3), ink and color on paper, ca. 1814. Photo: Public Domain.

- Katsushika Hokusai, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, Kinoe no Komatsu (Volume 3), ink and color on paper, ca. 1814. Photo: Public Domain.

- Hokusai Katsushika (?), Sailing, Sailing (discrete version). Edo, Japan, 1812 CE. Image: Public Domain.

- Hokusai Katsushika (?), Sailing, Sailing (indiscrete version). Edo, Japan, 1812 CE. Image: Public Domain.

- Blank back, Trick Postcard (Shikake-e), ca. 1900, Japan. Photo: With permission of https://www.shungaisart.com/

- Woman Raking, Trick Postcard (Shikake-e), ca. 1900, Japan. Photo: With permission of https://www.shungaisart.com/

- Woman Masturbating, Trick Postcard (Shikake-e), ca. 1900, Japan. Photo: With permission of https://www.shungaisart.com/

- Drawing of the common types of drawings of vulvas found in prehistoric art, based on figure by Cârciumaru, Lazăr, et al. Image by Mari H.

- Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, oil on canvas, 1814 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Photo by Jean Louis Mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- J.-A. Moulin, Photograph of a nude woman, based on Ingres’s The Grand Odalisque (1854). Photo: Public Domain.

- Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Turkish Bath, oil on canvas glued on wood, 1862 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Photo by Grégory Lejeune, Public Domain.

- Muhammad Qasim, Portrait of Shah Abbas I and his Page, ink and color on paper, 1627 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Photo: Public Domain.

- Barberini Faun, marble, ca. 220 B.C.E. (Glyptothek, Munich). Photo by Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Barberini Faun, back, marble, ca. 220 B.C.E. (Glyptothek, Munich). Photo by Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Barberini Faun (Detail of Face), marble, ca. 220 B.C.E. (Glyptothek, Munich). Photo by Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Painter of Pédieus (?), Erotic scene on the rim of an Attic red-figure kylix (wine cup), terracotta, ca. 510 B.C.E. (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 3.0.

- Workshop of Nikosthenes, Kylix, Athens, Greece, 530/520 BCE. Art Institute of Chicago. Photo: Lucas Livingston, CC BY 2.0

- Bomford Cup, underside, terracotta, ca. 530-515 B.C.E. (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford). Photo by Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Bomford Cup, interior, terracotta, ca. 530-515 B.C.E. (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford). Photo by Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Sleeping Figure, marble, ca. 150-140 B.C.E., on marble cushion by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1620 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Photo by Pierre-Yves Beaudouin, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Sleeping Figure, marble, ca. 150-140 B.C.E., on marble cushion by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1620 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Photo by Pierre-Yves Beaudouin, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Kandariya Mahadeva Temple, ca. 1030 (Khajuraho, India). Photo by Ramón, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (Detail of Decoration), ca. 1030 (Khajuraho, India). Photo by deepgoswami, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

- Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (Detail One), ca. 1030 (Khajuraho, India). Photo by deepgoswami, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

- Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (Detail Two), ca. 1030 (Khajuraho, India). Photo by Kkavita, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (Linga), ca. 1030 (Khajuraho, India). Photo by Rajenver, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Masaccio, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, fresco, 1426-7 (Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence). Photo by carulmare, CC BY 2.0.

- Michelangelo, The Fall and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1508-12 (Vatican City, Rome). Photo by Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0.

- Hans Baldung Grien, Adam and Eve, woodcut, 1519 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Photo: Public Domain.

- Aphrodite, Roman, 1st or 2nd century CE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Public Domain.

- Hans Baldung Grien, Death and the Maiden, oil on panel, 1518-20 (Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel). Photo by Perledarte, CC BY-NC 2.0.

- Penis Pinching Its Nose Inside a Vagina, Moche Culture, Peru (Museo Arqueològico Rafael Larco Herrera, Lima). Photo by Laslovarga, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Stirrup Spout Bottle with Couple, ceramic, slip, pigment, ca. fourth-seventh century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Photo: Public Domain.

- Miron Zownir, Untitled, 1984 (Hamburg, Germany). Photo: Permission granted by Miron Zownir.

- Gustave Courbet, L’Origine du Monde, oil on canvas, 1866 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Photo by Jean Louis Mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Édouard Manet, Olympia, oil on cavnas, 1863 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Photo: Public Domain.

- Édouard Manet, Olympia (Detail of face), oil on cavnas, 1863 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Photo: Public Domain.

- Édouard Manet, Olympia (Detail of hand), oil on cavnas, 1863 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Photo: Public Domain.

- James Heaton and Toyoshima Mizuho, “Hokusai’s Octopi and the Maiden,” Kyoto Journal 18 (1991): 15. ↵

- See: Marin Cârciumaru, Iuliana Lazar, Elena-Cristina Niţu, and Minodora Ţuţuianu-Cârciumaru, "The Symbolical Significance of Several Fossils discovered in the Epigravettian from Poiana Ciresului-Piatra Neamt, Romania," Preistoria Alpina 45 (2011): 33-44, 41. ↵

- See: Marin Cârciumaru, Iuliana Lazar, Elena-Cristina Niţu, and Minodora Ţuţuianu-Cârciumaru, "The Symbolical Significance of Several Fossils discovered in the Epigravettian from Poiana Ciresului-Piatra Neamt, Romania," Preistoria Alpina 45 (2011): 33-44, 41. ↵

- "Portrait de Shah Abbas Ier et son page, Muhammad Qasim," The Louvre (2023): https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010321123 ↵

- Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997), 164-165. ↵

- Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art (London: Phaidon Press, 1997), 166. ↵

- Genesis 3:24, New International Version. ↵

- “Virgil Ortiz Biography,” Blue Rain Gallery. Site is no longer active, but is archived on the Wayback Machine: https://web.archive.org/web/20060326210850/http://www.blueraingallery.com/artists/virgil_ortiz/9999. ↵

- "Taboo: Artist Statement," King Galleries (no date). https://kinggalleries.com/virgil-ortiz-taboo/ ↵

- "Taboo: Artist Statement," King Galleries (no date). https://kinggalleries.com/virgil-ortiz-taboo/ ↵

- Miron Zownir, interviewed by Bennet Togler, Eyemazing 2 (2006), 71. ↵

- Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, trans. by Ralph McCarthy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 42. ↵

literally "pictures of spring," Japanese woodblock prints, esp. ca. 17th-19th centuries, though also later, that feature explicit sexual content

literally "pictures of the floating world," Japanese woodblock prints, ca. 17th-19th centuries that focus on the lively activities of the red-light district of Edo (now Kyoto), including sumo wrestlers, geishas, and actors

a form of printmaking where a wooden block is carved in reverse, inked, and then pressed into paper to create an image

Resembling a vulva

in art, based on feminist theory: a specific, gendered, sexualizing look from a straight man at a woman, conveying an imbalance of power

Japanese woodblock prints generally containing images and poetry, privately commissioned in small runs to celebrate special occasions

the process by which viewers of films make connections between sequential shots, even when they may have nothing to do with one another. Named for Russian film-maker Lev Kuleshov

military dictatorship of Japan, 1192–1867, under the nominal control of the emperor

a follower of the religion of Buddhism

the area on a body containing pubic hair and external genitals

historically, a female concubine or sexual slave in a harem, esp. of the Sultan of Turkey. Also, a frequent subject for Orientalist painting

term for 19th-century European scholars who studied Asian cultures; also used to describe the approach of such scholars. Widely condemned in more recent post-colonial scholarship as racist and sexist.

loose, curving, irregular lines like those found in nature

The divide in an image between sky and land or sea

a round format for two-dimensional works of art, esp. paintings

one who finds sexual pleasure in viewing naked people, people engaged in sex, etc., esp. if those viewed are unaware of the viewer's presence

in ancient Greek myth, the goddess of beauty, love, and sex; equivalent to the Roman Venus

in ancient Roman myth, the goddess of beauty, love, and sex; equivalent to the Greek Aphrodite

Ancient Greek period from the death of Alexander the great in 323 B.C.E. to the rule of Augustus, first emperor of Rome in 31 B.C.E. Characterized by exaggerated forms and emotions

a wide, shallow Ancient Greek drinking cup

in the ancient world, a dinner party centered on wine drinking, with conversation on a chosen theme, and often ending in a sexual orgy

ancient Greek pottery style in which figures are left the reddish color of unpainted terracotta clay, against a glazed black background