6 Religion

Introduction

For much of the history of the world, religion has been a dominant theme in the visual arts. This is the result of factors ranging from personal to societal to economic. Individuals wishing to earn the favors of a deity might commission a statue of the god, or even of themselves praying to that god. Others might carve or paint images of their gods themselves as acts of devotion. Whole villages, cities, and countries, or their rulers, might commission works to declare their allegiance to a god. Large-scale temples and churches often require patronage of this sort. Indeed, works that survive from ancient civilizations are usually made of the most durable materials like stone and precious metals, which are also the most costly. Over the course of centuries and millennia, the majority of more modest artifacts are lost, which influences our understanding of their periods.

This chapter examines a range of spectacular works created to express religious beliefs, please gods, and influence human affairs through supernatural forces. They convey but a small sample of the thousands of religions that have existed, starting with one of the oldest known paintings in the world and including works from Greece, Japan, England, China, Papua New Guinea, France, Afghanistan and on, ranging from 32,000 years ago up to the twentieth century.

SPOTLIGHT IMAGE I:

Cave Painting, Grotto Chauvet, France, ca. 30,000 BCE

VIEWING QUESTIONS

- What compositional devices are used, and what effects do they create?

- What techniques are used to give the figures bulk and weight?

- How is line used?

- How is scale used?

VISUAL ELEMENTS

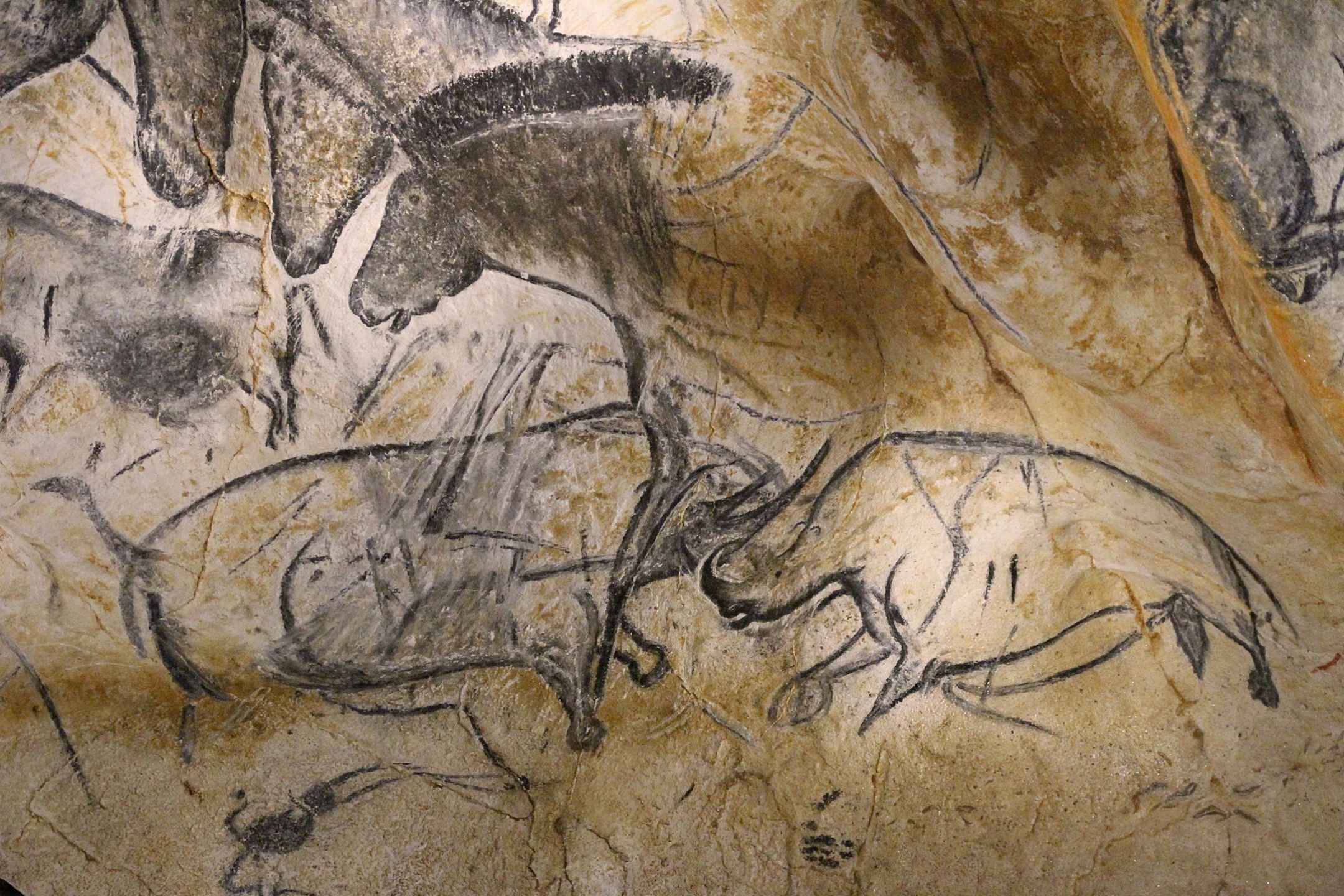

The “Panel of the Horses,” as this group of prehistoric wall paintings is called, is a massive group of animals, with woolly rhinoceroses, large felines, horses, bison, reindeer, aurochs (an extinct giant ox), and even possibly a mammoth. Most of the figures seem to charge from right to left across the wall for nearly 7m (21ft). They have a tumultuous energy that is most concentrated toward the left edge of the composition. This is achieved through density – the figures are much closer together, and there is much less blank space around them. They overlap and blend into one another.

From a distance, the composition looks like a massive herd stampeding across a landscape. On a closer look, though, the unity of the composition breaks down, largely through the use of scale. Figures that are drawn and painted right next to or on top of one another are at times drastically different in scale.

In the detail of horses above, the set of four horses at the center are all roughly the same size. The way that they overlap has been interpreted by some as an effort to create perspective, so that the animals seem to recede into the distance in illusionistic space. The use of shading on the heads, which gives a sense that they are three-dimensional, does suggest that the artist(s) did want to create some illusion of space. However, the horse that appears closest to us is the smallest, which counters this illusion; the furthest away ought appear smallest.

In contrast to the four horses, which are close enough in size to seem like a cohesive unit, the leftmost edge has three aurochs with their heads pointing at a relatively tiny pair of woolly rhinoceroses. Similarly, below the lowest of the aurochs is a small figure, just roughed in, that may represent a woolly mammoth, facing to the left with its trunk hanging down. All throughout the composition, figures overlap in sharply contrasting scales, suggesting that there is no attempt to create a unified composition depicting a continuous illusion of space.

If the animals are not all in the same space, then it is unlikely that they are all moving together. Instead, it seems that there are a number of separate images and events, loosely connected. Each, though, might be taken in a number of ways. The horse heads, for example, might be in an overlapping sequence to show depth through perspective. They might just as well show a single horse in a range of poses, so that each represents the same horse at different times, as it tosses its head. Or maybe the front-most image presents a pony, in which case, this could be the same horse at four different times in its life. It is also possible that they are only connected conceptually, and that we are not to read any particular movement through time or space as we look from one head to the next. Indeed, they could be four independent images having nothing in particular to do with one another beyond location and subject matter. With prehistoric art, we can rarely be certain, since their creators did not have a written language to tell us what the artists intended or what the original audience thought.

Below the horse heads, we see a pair of woolly rhinos facing one another. Again, we might read this any number of ways. The shapes of the contour lines that define the forms suggest that they are charging toward one another. The rhino on the right has very small hindquarters. The form then swells dramatically as we move toward the forequarters, so that it seems to concentrate all of its bulk and energy into its lowered head. In a similar way, the rhino on the left is abbreviated to the rear – the hind legs are not even drawn in – and the form swells to a great hump over the lowered head, again conveying a sense of the figure driving forward. They therefore seem to meet with a powerful crash.

However, it has been observed that modern rhinos in the wild rub their horns together in gestures of friendly greeting, which might well be what is going on here. Finally, though, as with the rhinos positioned in front of the aurochs heads, it is possible that these two animals are not placed together to create a unified scene. Their overlapping may not indicate any direct spatial relationship, since seems likely that many of the overlaps throughout the wall do not.

In our visual analysis, we must bear in mind the setting for this wall of images. It is located some 150m (450ft) into the cave, in total darkness. It is next to a large block of stone that has the skull of a cave bear (an extinct species larger than the grizzly) atop it, and other cave bear skulls are on the floor around it. As prehistoric anthropologist and art historian Christine Desdemaines-Hugon writes:

Lit by the wavering flames of tallow lamps, torches, or small fires, all the animals would spring to life, appearing to move, sway, expand to larger proportions, or momentarily disappear.[1]

CULTURAL CONTEXT

Prehistoric art is, in a way, the ideal form of art for an art appreciation textbook. With works from the historical era – that is, works made by literate cultures – we have a wealth of contextual information: names, dates, key events, religious texts, poetry, royal genealogies, and so on. But for prehistoric art, the main evidence we have to consider is visual. Certainly, we can learn a lot based on the location of the works, archeological evidence about their makers, and other contextual evidence, but the main source for information about a prehistoric work remains the work itself.

Our species, Homo sapiens (Latin for “wise man”), evolved approximately 400,000 years ago, and our subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens (“wise, wise man”!), evolved in Africa, possibly as early as 120,000 years ago, spreading from there to eventually occupy all the continents of the earth. The Chauvet Cave paintings are Paleolithic (from the Greek words for “old stone”). The period ran from approximately 2.6 million years ago (when the earliest stone tools were developed by our evolutionary ancestors) until about 10,000 years ago, ending along with the last ice age and accompanied by the development of agriculture in the Neolithic (“new stone”) period.

The paintings in Chauvet Cave are among the oldest known, from 32,000 years ago, and yet it is striking how readily modern viewers respond to them. The naturalism and close observation of animals is startling, especially as it is commonly assumed that art had to slowly progress from a “primitive” state toward naturalistic representations. Quite to the contrary, here at the very beginning of the artistic record, we find carefully observed animals, depicted with a sense of depth and movement.

We also, though, find striking abstraction, as in the simplified form of another rhino, seemingly drawn in a single contour line that defines the whole animal, and with just a few small additions of dots or lines to add the tail, eye, perhaps an ear, and some shading or nostrils below the large, elegant horn. In addition, there is the curious grey belt around the rhino’s swaying belly, which does not seem to be quite representational. With great economy, the artist gives a sense of the creature and, contrary to common belief, this abstraction may present a greater conceptual challenge to artists than naturalism.

What does this cave have to do with religion? In assessing any work of art, we should always ask “What was this made for?” The people who created such works did not live in the caves they decorated, where were very humid, stifling places, absolutely dark and without ventilation for fires. The caves, then, must have served a function other than shelter. They could not really be seen as prehistoric art galleries, as the works are highly inaccessible and, because of the darkness, almost impossible to see.

If these paintings were not there to be seen, what were they for? Anthropologists suggest that they were probably used for any number of activities that we might now call “religion”: Shamanism, animistic worship, totemic practices, or other forms of worship and ritual about which we know little. The images are mostly of animals that were not used for food, so they are probably not tied to hunting magic, but might instead be connected with fertility or power.

The great abundance of animals here and in other Paleolithic caves may suggest – or be intended to magically invoke – a fertile world that provides for the tribe so that these early humans can reproduce, as well. Some caves bear traces of ritual uses – evidence of music, suggestions of altars or offerings – that also points toward a belief in the supernatural. It is unlikely that these Paleolithic people had highly formalized religious traditions, but they almost certainly did have beliefs in supernatural powers or entities, and developed practices – including the creation of visual images – designed to access and influence them.

Because they did not write down their beliefs and intents, we cannot be certain. But the very existence of these works, produced by hunter-gatherer societies struggling for their basic survival, speaks volumes. These are not the decadent products of a leisured group. Producing them would have been very strenuous, with artists needing to crawl through narrow passages, pulling their fat-burning lamps, tools and even scaffolding with them. Viewing them would require similar efforts. Whatever the specifics of their function, these works were created with tremendous effort, skill and care, all of which suggests that they believed that creating these images – which were not designed to be viewed by many people, if any at all – would be helpful to them. We might speak of magic, and we might just as well call it religion.

Comparisons and Connections I

Chauvet Cave is a remarkable work that suggests that humans have imagined concepts of the supernatural from our earliest moments as a species. We cannot know the specifics of the beliefs of this group of people and the rituals they developed around them since the cave’s artists left no writings, but we can hypothesize about them. We can be fairly certain that, whatever they intended as they crawled through narrow openings, dragging their supplies with them into stifling, pitch-black caverns, the images these prehistoric people produced were not for mere decoration, not for entertainment or idle fun.

This section will discuss a series of works of art and architecture that were designed with religious intentions. Most will be from literate cultures, so their writings will help to answer many questions more precisely. The examples will vary greatly, including idols constructed to house gods, images reflecting devotion, scenes designed to inspire greater piety, and works to connect with supernatural beings and forces. Each should inspire reflection on Chauvet Cave and its potent imagery.

If the cave paintings might suggest some form of nature worship, this would recall many similar beliefs from throughout world history. The native religion of Japan, Shinto, is focused on kami, millions of nature deities that inhabit aspects of nature, like trees, rocks, waterfalls, and animals, which then become sites of worship. Originally, Shinto was not a codified, formal religion, though it later became more firmly based on rituals.

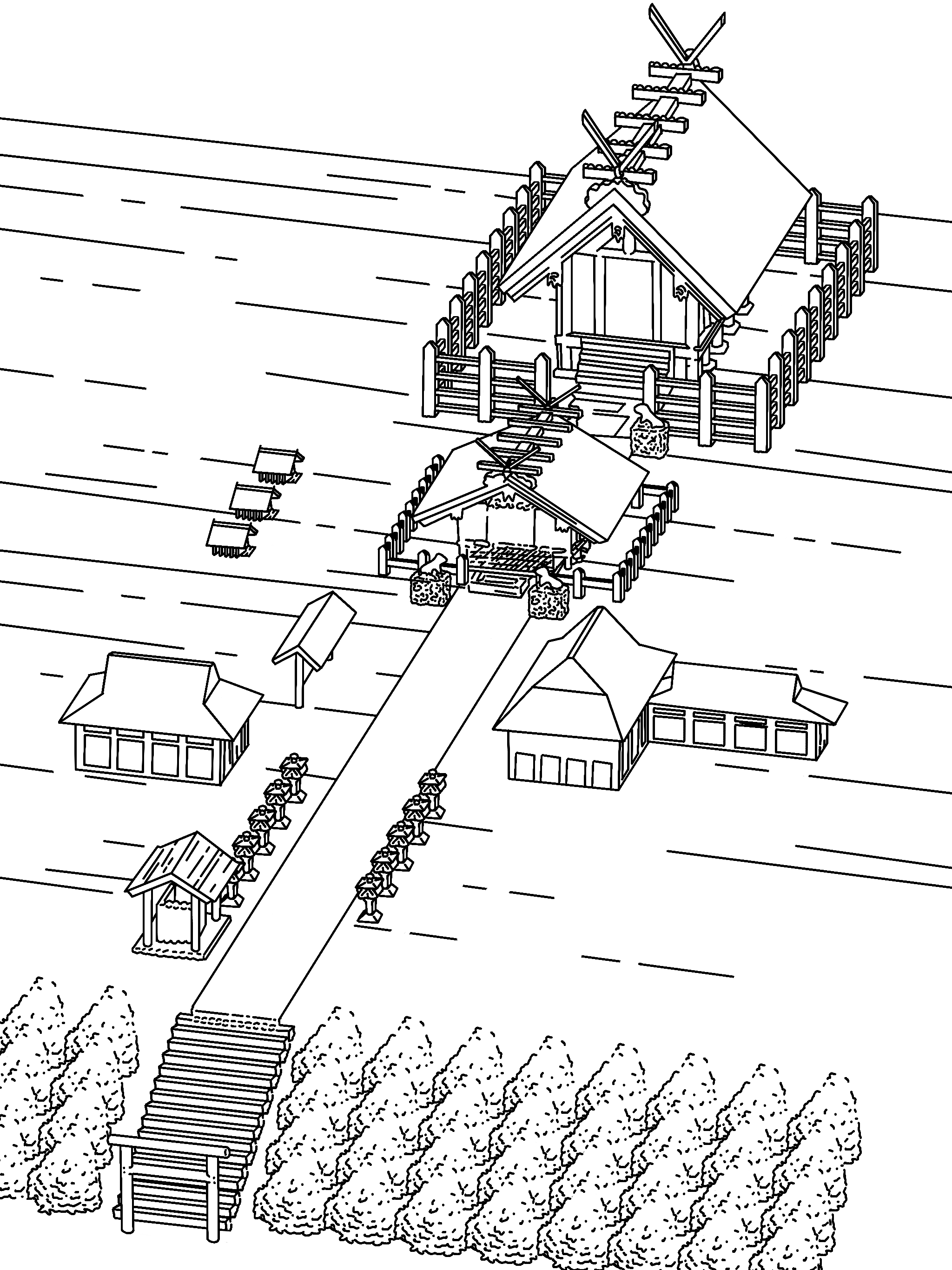

The Shinto Shrine at Ise, officially known as Jingu, is one of the most famous religious sites in Japan and Shinto’s central one. It embodies many aspects of this nature religion in its design. It is built entirely of unfinished natural materials, with cypress walls and beams and a thatch roof. As a result, it cannot endure the Japanese climate for very long, and needs to be periodically rebuilt. Scholars believe that it was originally built in the first century CE, and then rebuilt in a time of cultural change in the seventh century. Since then, craftsmen who train for a lifetime rebuild it every twenty years. Their work building it is an act of devotion. The techniques and materials are consciously old-fashioned, but the resulting shrine appears fresh. It was last rebuilt in 2013, and will be rebuilt again in 2033. This might be seen as a reflection of the core Shinto practice of ritual purification as a form of renewal.

The shape of the shrine is based on raised granaries for food storage, designed to keep grain away from pests, but this became standard for Shinto shrines. The shrine at Ise is dedicated to Amaterasu-o-mi-kami, the sun goddess and mythical ancestor of Japan’s imperial family. Therefore, the shrine is only used by the imperial family and its priests, and remains off-limits to the public. It originally housed several sacred objects, including a mirror associated with Amaterasu and seen as embodying notions of purity, honesty and sincerity. These same values are also emphasized by the simple, raw, unadorned materials of the shrine.

Still, Jingu is an impressive monument. Like most high-status religious structures, the shrine is symmetrical, which makes it seem stable and dignified. It is set at the end of a long path, behind a series of gates that serve to keep out most visitors but also provide a sense of entering into a sacred space for those priests and members of the imperial family permitted within. Like Chauvet Cave, the deeper within the space, the more sacred the atmosphere.

A similar technique is used at the Great Stupa in Madhya Pradesh, Sanchi, India, constructed from the third century BCE through the first century CE. This major Buddhist pilgrimage site was built using donations by pious individuals to house the relics – the physical remains – of the Buddha. It is again removed from daily life; in this case, the whole complex is located only a short distance from the city, but through its design, the sacred center is set off from worldly activities.

Surrounding the mound of the main stupa is a large stone fence with four thirty-five foot tall stone gateways, or toranas, located at the four cardinal directions (North, South, East and West). These gateways are open, so they do not function like those guarding the entry to Jingu. Instead, they function to help pilgrims – people who travel to holy sites for religious reasons – transition from the ordinary world outside the gates to the sacred space within. Indeed, the Buddha is said to have requested to be interred at a crossroads, so that it would be easier for travelers to visit the site.

Unlike Chauvet Cave, the intent here was for the imagery to be as clearly visible to as many people as possible. The toranas are the only part of the Great Stupa to have sculpture, which was again aimed at pilgrims. Pilgrims first walk around the exterior, looking at the images while meditating, and then enter through a torana and circle the stupa, itself, again looking at the imagery on the toranas. Buddhists believe in reincarnation – the notion that people are reborn into new bodies when they die – and many of the carvings show scenes from the Buddha’s past lives, as well as real and mythical animals, and other beings.

Perhaps the most compelling of these are the yakshis and yakshas, female and male benevolent minor deities common in Indian belief and found in both Buddhist and Hindu art.

One such yakshi hangs lightly from a branch. Her sensuous body nimbly sways, her legs gracefully crossed at the shins. She has full breasts and her genitals are revealed through the diaphanous skirt she wears, only visible because of its hem that cuts across her anklets. These attributes forcefully convey a sense of fertility, perhaps further emphasized by the great phallic trunk of the elephant that approaches her from the left. She is a personification of water, and therefore of the source of life. At her touch, the tree seems to explode with its bounty of fruit.

While the toranas are covered in compelling images, there are no images of the Buddha, himself. He is, instead, shown through his absence, though images of his footprints, empty thrones, and the like.

In strong contrast, in Ancient Greece, images of deities were seen as necessary for worship. The religion of the ancient Greeks was polytheistic – they worshiped many gods. Worship was conducted through sacrifice to the gods, but in order for the sacrifice to be meaningful, the god had to be present. Sculptors were therefore commissioned to create impressive images of the gods that served as idols, as images to be inhabited by the gods. Works like the impressive Bronze Zeus of Artemision (ca. 460-450 BCE) were not merely decorative or instructive, not designed just to give viewers an idea of what the god looked like or to teach worshippers about him. Instead, it was designed to entice the god, or at least some portion of his divinity, to enter the statue, which would then serve as an object of devotion and sacrifice, as may have been the case at Chauvet Cave.

The figure is majestic. While the body is naturalistic, it is also highly idealized, with firm muscles that seem at odds with the age of the long-bearded figure. He once held a thunderbolt in his right hand, which is how we can tell that the figure is Zeus, the supreme deity of the Greeks and ruler of the sky. The figure does not have any inscriptions on it, and yet we can be sure it is a god because of the manner of his depiction. The figure’s intent is clear: He is about to hurl his thunderbolt, probably to destroy a mortal person, and yet his face is utterly impassive. It is rigidly symmetrical, with even his hair falling in paired locks from the center, outward along his forehead. The god’s expression is fixed, as he looks down on his victim without a trace of mercy.

Early Christians, living in a Greco-Roman world where this sort of imagery was the standard, sought an image of their new god that would be greatly at odds with the often-merciless polytheistic pantheon.

An early sculpture of Jesus Christ as the Good Shepherd from the late third century CE is typical of this period. Here, instead of the older, powerful, domineering image of Zeus or Poseidon, Jesus is youthful, soft, and gentle in appearance. His body is still naturalistic and idealized, in that it seems young and healthy, but in place of the muscular nude of the Greek god, he is modestly clothed in the robes of a simple shepherd. Jesus carries a lamb on his shoulders, in reference to a series of passages from the Bible, for example Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not be in want…”) and Jesus’s Parable of the Lost Sheep:

Suppose one of you has a hundred sheep and loses one of them. Does he not leave the ninety-nine in the open country and go after the lost sheep until he finds it? And when he finds it, he joyfully puts it on his shoulders and goes home. Then he calls his friends and neighbors together and says, “Rejoice with me; I have found my lost sheep.” I tell you that in the same way there will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who do not need to repent. (Luke 15)

In essence, the message conveyed is that the viewer is the lost sheep, or at least might be, and that Jesus, unlike the Greek and Roman deities, cares about each person as the shepherd cares from his lost sheep. The Greek god stared down at his human victim coolly, without emotion; Jesus instead looks out at the viewer with a slight smile, and maybe even with expression of relief on his face. The message of such images was clear and persuasive to many: this was a god that cared about his followers.

About eight centuries later, when a depiction of the Last Judgment was carved over the west entrance to the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare in Autun, France, ca. 1130 CE, Christianity had become the most common religion in Europe. Christian art was therefore no longer primarily focused on winning new converts. With new goals come new styles. In this tympanum – the semicircular sculptural panel over the doorway – the image of Jesus is no longer naturalistic. Instead, it is highly abstracted, elongated dramatically and flattened out. Unlike the Greek god, he seems almost passive, elevated in the mandorla – the full-body halo that surrounds him – but also contained by it.

The composition relies on hieratic scale, with the importance of Jesus conveyed by his enormous size; angels and saints (Christian holy figures) are half his size, and ordinary people, below their feet in the lintel running across the bottom of the image, are shown as tiny, fragile figures, cringing and cowering as they approach the moment of their judgment.

In Christianity, the Last Judgment determines whether the souls of the dead will rise to the joys of heaven or descend to the torments of hell for all eternity. Emphasis is no longer on Jesus as the savior of lost sheep and protector of his flock. Instead, Jesus is now more impassive, showing no more visible compassion to those on his left being pulled and pushed into the mouths of hell than the Greek Zeus showed to his victim.

The whole composition is roughly symmetrical, with elements arranged on either side of the central figure of Jesus. Components on each side balance those on the other without exactly mirroring them. Architectural elements like arches and columns divide the image into sections. The effect is of an elaborate cosmography – an understanding of the organization of the universe – centered explicitly and absolutely on the massive figure of Jesus at the center.

In contrast with Chauvet Cave, where there was no clear principle of organization that dominated the full image and no clear relation between the animal figures throughout it, here everything is ordered and precise. All relationships between figures are clearly defined. This visual difference likely reflects substantial differences in the religions of their creators. On the other hand, the Last Judgment tympanum at Autun can be connected to Chauvet Cave in that it, like the toranas of Sanchi and the gates of Jingu, marks the entrance to a sacred space, and within that cavernous space, ritual and belief join to create the religious experience.

The north portal of the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare has been damaged and rebuilt, but sculptures from the original design survive, including a sinuous image of The Temptation of Eve. At this point in the story, the monotheistic god Yahweh, shared by Judaism, Christianity and Islam, has created Adam and Eve and placed them in the Garden of Eden, a place of ease and innocence with only one rule, recounted in Genesis 2:17:

You must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat of it you will surely die.

We find Eve as she picks the fruit in an oddly distracted manner. She has a dreamy expression on her face, and reaches casually behind her to pull the fruit from the tree. Only a close look reveals the clear danger of this act: at the right edge of the image, where the branch of the tree of knowledge bends sharply toward Eve, is the claw-like hand of the devil.

The rest of the figure is now lost, but this sharp-taloned remnant, grasping the branch and bending it toward the distracted figure of Eve, serves to suggest the significance of this otherwise peaceful scene.

Eve is completely without clothes, but unlike the artist of the Yakshi discussed above, the artist here relied on a strategically placed plant to cover her groin. This is an image about the dangers of sexual temptation, rather than about the wonders of fertility and bounty. The strong horizontality of the image emphasizes her lowliness. Her body snakes through the underbrush and she is surrounded by twisting, serpentine plants. Even a lock of her hair zigzags like a snake along her arm. Indeed, all of the lines in this image twist and turn, so that the viewer connects Eve with the serpent, the form of the devil in this part of the biblical narrative. The visual association of the serpent and the plants fosters a suspicion that the natural world itself is dangerous, not beneficial.

We can find strong contrast in the religious views of nature not only in the teeming images of Chauvet Cave, but also in the lush foothills of northern New Guinea, the second-largest island in the world, which bears both tropical rainforests and snow-capped, 16,000 foot mountain peaks. This is the home of the Abelam, among whom male status is based on participation in the Tambaran (“Men’s House”) cults, central institutions in their society. These cults have a strong influence on art and architecture. The giant, human-sized yams at the heart of the cult – not the usual variety grown for food, and sometimes themselves considered works of art – are associated with ancestors and with the potency of their growers.

During the annual harvest festival, the spirits of ancestors are believed to inhabit the yams. Their presence is reinforced by placing yam masks atop the yams, which are also dressed in full ceremonial regalia. These mask are only loosely anthropomorphic – that is, having human qualities – with highly abstracted features. On this mask, as is frequently the case, the eyes are highly emphasized, so that the ancestor seems to be present and watchful. They also wear elaborate headdresses, like those worn by Abelam men, to indicate their status. The images, then, like the images of Chauvet Cave, suggest fertility and abundance, as well as ancestry.

The growing of these remarkable yams is, for the Abelam, a secret activity undertaken by the members of the yam cult composed of initiated men and centered on the Korambo or Ceremonial House used to store and hide the images of the yam cult until the annual festival. The massive structure (280 by 40 ft), the size of which denotes its importance, is covered with extensive images of ancestors. They are painted on the ends of the long structure, on the deep overhangs beneath the central ridgepole. This pole, running along the peak of the roof and projecting out at both ends, is seen by the Abelam as phallic.

The faces that fill the pointed front of the Tamberam House are, like the yam masks, abstracted images with large, staring eyes. They are nearly identical, establishing a strong pattern that emphasizes the unity of the group.

As in Chauvet Cave, Tamberan House interior images do not seem to belong to a rigidly ordered composition. Indeed, sometimes the painted images in this cavernous space – seen as womb-like, in contrast to the phallic pole outside – do not correspond at all with the carved surface beneath, possibly because they are, as with some of the overlapping figures at Chauvet, simply independent of one another.

What matters here is not some sort of naturalistic representation but rather, the power of the image, produced with paint believed to possess magical powers. While the interior images are not as precisely patterned as those on the exterior, they nonetheless hold together to produce a cumulative effect. They so thoroughly cover the interior that, when viewed along with freestanding carved ancestor images, the yam masks, and the yams, themselves, members of the yam cult would seem to be surrounded on all sides by their revered ancestors.

SPOTLIGHT IMAGE I:

Great Mosque, Córdoba, Spain, 756-1031 CE

VIEWING QUESTIONS

How is the space organized?

How is rhythm used?

What is the role of texture on the surfaces?

What is used to emphasize elements?

VISUAL ELEMENTS

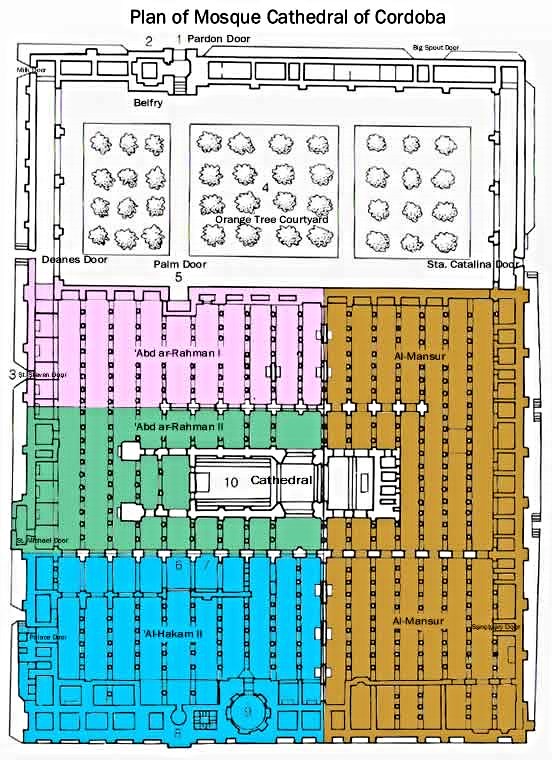

Upon entering the main prayer hall of the Great Mosque in Córdoba, Spain (756-1031 CE), the visitor is greeted with an overwhelming vista: row upon row of columns stretch into the distance in all directions. The hall is approximately 410 ft wide and 330 ft long (125 x 100m), and was at its height filled with 850 columns (though later renovations cut this number significantly). This massive structure was not built to its present size all at once, but rather, grew over nearly three-hundred years – always in the original style – in order to keep pace with the growing Muslim population of Córdoba to well more than twice its original area.

The columns used for the first phase of construction were spolia – pieces reused from earlier buildings, in this case reused from Visigothic Christian churches. This may have been done largely to save money, but might also have conveyed to any who recognized these columns the supremacy of Islam over Christianity. In the thirteenth century, after Córdoba had been conquered by Christian forces, a cathedral was build right in the center of the mosque, reversing the declaration of cultural dominance.

The Visigithic spolia columns are relatively short and so, in order to raise the vaults, the designers created a system of double-tiered arches. Each of these arches is horseshoe shaped, so that they curve back inward at their base. This has no structural benefit, so it is simply decorative.

The visual effect is of stunning complexity, enhanced by the use of alternating bands of red and while on the arches. In the oldest arches, this pattern is the result of alternating courses of bricks and stone, which is probably the origin of the style, but in most of the hall, it is merely a pattern painted on plaster.

Because the original columns and capitals were from other buildings, they were not all the same color, size or shape, so there is a bit of irregularity in this otherwise rigidly ordered space. Instead of distracting, this slight inconsistency lends a bit of life and energy to the space, with the leaf carvings on the capitals making it seem almost as if the hall were a natural forest with the arches branching out from the columns to create a steady visual rhythm.

While the banded, double-tiered arches seem visually complex, other elements of the mosque are far more ornate. In front of the mihrab – a niche in the wall of a mosque facing toward Mecca and therefore signaling the direction of prayer – is a series of arches of stunning elaboration. These arches consist of two levels of scalloped elements, capped at the top with a row of horseshoe arches. These are all covered in intricate panels of patterned foliate – that is, leaf-like – designs, produced in plaster.

Looking upward to the small multi-lobed dome above, the viewer is confronted with still increasing degrees of complexity and ornamentation. The dome is octagonal, and is supported on eight interlocking arches, which are supported on eight horseshoe arches, supported on small engaged columns and pilasters, all of which in turn rests on the series of horseshoe arches above the scalloped double-arches. Everything here is covered in elaborate foliate and geometric patterning, and much of it is covered in gold. This is far more effort than needed to support this small dome. It was done for the visual effect, which is stunning.

Running around the base of the dome in the octagonal band just above the supporting arches is an inscription in orange letters on a blue background. Based on the Qur'an, verses 22:77-78, the inscription directly addresses the viewer:

O you who believe, bow down and prostrate yourselves, and adore your Lord, and do good, that you may prosper. And strive in His cause as you ought to strive, He has chosen you and has imposed no difficulties on you in religion, it is the religion of your father Abraham; it is He who has named you Muslims, both before and in this (Revelation), that the Apostle may be a witness for you.[2]

This inscription stresses that prayer is the essential element of Islam, a concept reinforced by other inscriptions in the mosque.

Inscriptions throughout the mosque describe the nature of the god of Islam. For example, an inscription beneath the dome, written in the horizontal band above the arch leading to the mihrab, contains another verse from the Quran (59:23). It reads:

God is He, [other] than whom there is no other god, who knows [all things], both secret and open; He, most Gracious, most Merciful.[3]

In Islamic art, such inscriptions become major decorative elements. This is probably the result of the Muslim prohibition on the depiction of human and divine figures. Without figures of God, or of Muhammad and other major figures, artists turned to lines from the Qur’an, believed to be the word of God. This inscription is fitting, as it marks the entrance to the mihrab that indicates the direction for prayer. Taken together with the elaborate decorations, it is clear that the viewer is to pray in this direction toward a solitary, gracious, and merciful god.

CULTURAL CONTEXT

Mosques are Muslim places of worship, and Muslims are the followers of the religion of Islam, currently the second most populous religion in the world (after Christianity) with about 1.5 billion followers. It was founded by Muhammad, born in Mecca ca. 570 into the family of Ishmael, the outcast son of Abraham, the Jewish patriarch, and his Egyptian concubine Hagar. Mohammad, a merchant, took shelter in a cave while traveling, and there, according to Islamic belief, the angel Gabriel appeared to him and commanded him to recite revelations from God.

From this point, forth, Muhammad is referred to as the Messenger of God and fought the polytheism then prevalent in Arabia, preaching instead that there was only one god (Allah in Arabic). Because of his unpopular beliefs, Muhammad and his followers were thrown out of Mecca in 622 and moved to Medina, a desert oasis. This flight, called the Hegira, marks the beginning of Islam as a religion, and marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar. In Medina, Muhammad preached and received further divine revelations, and then returned to Mecca with army of 10,000 followers. He then converted the population and had all of the idols destroyed.

Muslims view Muhammad as the third of three great prophets, following Moses and Jesus. Muhammad did not claim to be divine and did not perform miracles. Rather, he stated that he was a messenger striving to purify and perfect faith in God. Islam’s central principle is total “submission to the will of Allah,” which is the meaning of the word Islam. The main obligations of the religion are referred to as the Five Pillars:

- Making the profession of faith, or shahada: “There is no deity but God, and Muḥammad is the messenger of God.”

- Praying five times a day, facing Mecca (though generally, only the main Friday prayers are said in a mosque, and led by an imam)

- Giving alms

- Fasting during daylight hours for the month of Ramadan

- Making, if possible, the hajj, a pilgrimage to Mecca, once in a lifetime.

Muhammad was a secular ruler as well as the head of a new religion, and led the first of many conquests that helped Islam to spread remarkably quickly. By 711, less than one-hundred years after Muhammad was initially thrown out of Mecca, Islam had conquered all of the Middle East, North Africa, Egypt, and Spain. Monuments like the Great Mosque of Córdoba therefore marked not only religious belief but also secular conquest.

The Great Mosque was commissioned by Abd al-Rahman I, a noble of the Umayyad dynasty. The Umayyads had been massacred by their main rivals, the ‘Abbasids, and Abd al-Rahman I seems to have been the sole survivor. He fled from Syria to Córdoba, and spend the next three decades consolidating his power, which he ultimately marked with the construction of the mosque. The version commissioned was a rather more modest structure than that which we see, today, but even at its inception (the section in light blue in the plan above), it was a work of intricacy and delicacy, such that subsequent builders felt compelled to maintain the style established by the earliest portions.

The intense energy devoted to inscriptions and ornament in Islamic art and architecture results from what has been the prevailing Muslim interpretation of the biblical Second Commandment:

I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing love to a thousand generations of those who love me and keep my commandments.[4]

This is the primary texts with which Jewish, Christian, and Muslim artists have had to grapple in conceiving of their approach to art. Jews and Muslims have generally tended to take this text more literally, especially avoiding most depictions of sacred figures, above all else, of God.

Passages in the Qur’an echo and extend the Second Commandment. They read:

No visions can encompass Him, but He encompasses all visions.

My Lord, make this a peaceful land, and protect me and my children from worshiping idols.[5]

In works produced by aniconic groups – that is, those “without images” – other artistic elements may receive great attention. The lavish scripts used for Islamic inscriptions allow these words to stand in for the presence of God in mosque.

Comparisons and Connections II

The Great Mosque of Córdoba provides a powerful model of design used to celebrate religion, with row upon row of columns supporting intricate arches and elaborately inlaid inscriptions. The result is an overwhelming display of power and wealth, as well as religiosity. In this section of comparisons and connections, we will see a range of works grand and modest, figurative and aniconic, each of which makes a strong statement about the perspective of its patrons and designers. Some strive, like the Great Mosque, for grandeur and complexity. Others display a willful simplicity and austerity.

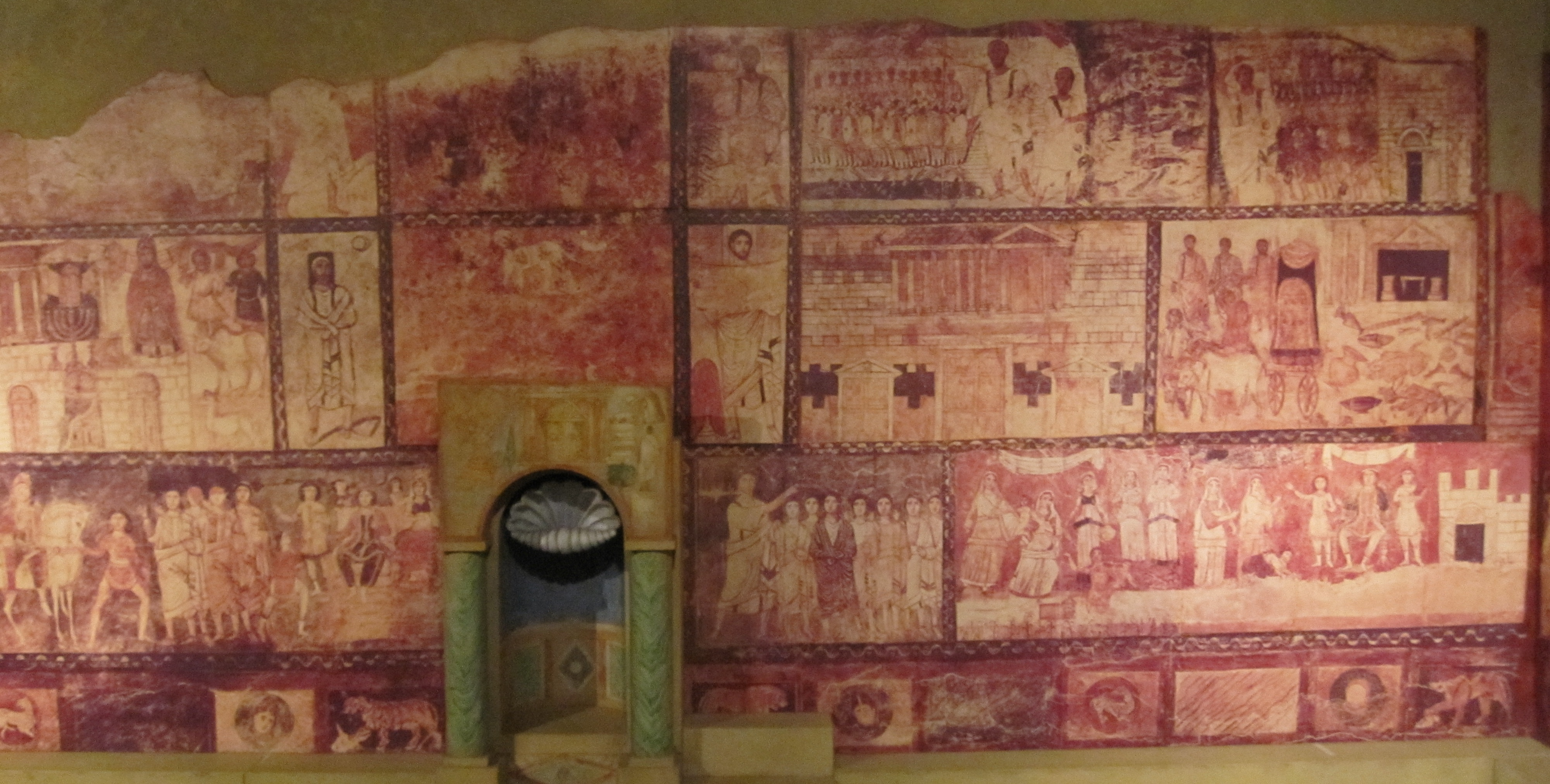

The synagogue at Dura-Europos, Syria, built between 244-245 CE, presents a very different model for dealing with the constraints of aniconism. In this ancient Jewish house of worship, among the earliest to survive partly intact, we find an overwhelming profusion of imagery. Images fill the walls of this poorly preserved structure. They contain narrative images telling stories from the Jewish bible, portraits of major prophets including Moses, Isaiah, and Jeremiah, and images composed of visual symbols central to Judaism (like those found on the oil lamps discussed in the Communities chapter).

Some of the images in the synagogue ironically seem to address the danger of images, and thereby provide cautionary instruction to their own viewers. The image of the Temple of Dagon shows the Ark of the Covenant – the shrine containing the original tablets of the Ten Commandments, carried by the Israelites through their wandering in the desert and then installed in the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem – being carted past a series of polytheistic idols including that of the Philistine god Dagon.

In the Ark’s presence, the idols spontaneously fall to the ground and shatter. This image about images directly contrasts the Ark, here depicted as an authentic source of divine power, with the idols, shown as false and powerless.

How are we to interpret this image that seems to be hostile to the creation of images? The contrast in styles between the fresco paintings of the synagogue and the idols they represent can help explain their existence. The fallen, shattered idols are shown to be sumptuous three-dimensional statues made of gold. They were set up in the temple in the background, recognizable by its white marble columns and triangular pediment, and, most importantly, they were worshipped there. This is exactly the sort of practice addressed by the Second Commandment quoted in full above. The key passage reads:

You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them.[6]

The frescos, themselves, in contrast, are two-dimensional, and the style is self-consciously flat. There is almost no effort to show, for example, that the Ark or the men who accompany it have volume. There is very little shading, and only the slight overlapping of the figures suggests that the group of three men is behind, rather than above, the man raising his arm to drive the oxen forward. They are very clearly just pictures, not gods, and they are there to instruct the viewers, not to be worshipped. They therefore follow the spirit of the Second Commandment, which is, in essence, not a prohibition against images, but against their worship.

Judaism developed in the Ancient Near East (more or less the region we now call the Middle East), where polytheistic image worship was the standard religious practice, and its rejection of images of God (eventually also embraced by Muslims), may have been largely intended as a mark of separation from the surrounding groups. Throughout the ancient world, though, from our earliest clear records of religious practices until the eventual spread of Christianity, image worship remained the primary religious activity. The most celebrated of ancient polytheistic temples is the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, designed by Kallikrates and Iktinos and built from 447-432 CE. This massive structure, very much the heart of ancient Greek religion, was built to replace a smaller temple destroyed by an invading Persian army in 480 BCE.

The Parthenon had more sculptures than any other Greek temple, as far as we can tell. It had a continuous band of sculptures running for 525 feet, as well as almost a hundred separate panels and, dominating the exterior, two triangular pediments containing fifty figures, all over-life size, and some colossal, all overseen by the master sculptor Pheidias. Still, all of this imagery was ultimately dwarfed by the thirty-eight foot tall chryselephantine – that is, covered in gold and Ivory – statue of Athena Parthenos in the interior. This statue, now destroyed, was not decorative or ornamental, as we might consider the artistry of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, nor was it educational, as with the images of the synagogue of Dura Europos. It was not an embellishment for the temple; rather, the entire rest of the temple was a house for it, and the rest of the sculptures serve to support, to prepare the viewer for the statue within. Through rituals now only known in part, priests would prepare the sculpture and encourage the god to enter it, so that at least a part of the deity’s divinity inhabited the work of art.

The Parthenon was first and foremost, like all ancient temples, a house for the god to live in. Visitors to the Parthenon, which sits atop the Acropolis – the raised, sacred precinct of Athens – would come to offer sacrifices before the statue. These would usually be in the form of animal sacrifices, burned before an altar that stood in front of the Parthenon, so that the smoke would rise up to Athena. The sacrifices needed to be made there because of the presence of Athena in the magnificent statue within the temple.

This is exactly the sort of practice rejected by both the Bible’s Second Commandment and by the Qur’an passages quoted above. However, sacrifices before images of gods was the dominant mode of religious practice in the Middle East and Europe from prehistory to until the spread of Christianity.

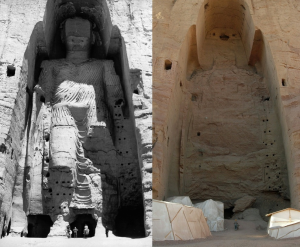

Image making practices are hardly restricted to the West. Throughout the world, we find images of gods and other sacred figures. Among the most impressive religious images ever produced are the Colossal Statues of Buddha from the valley of Bamiyan, Afghanistan, created in the fifth or sixth centuries CE. Bamiyan was a major center of Buddhist devotion, and over the centuries, devotees carved out approximately twenty thousand caves, some used for collective worship and study and others to house a single person. The most impressive of these were a pair of standing figures for Buddha, 136 and 186 feet tall, the largest Buddhist statues in the world, made between the second and fourth centuries. Visible from miles away, they were painted, the smaller blue and the larger red, with the hands and faces covered in gold, and they were surrounded with smaller painted and carved images. Like the similarly opulent image of Athena from the Parthenon, dwarfed by these giants, the Buddhas become spectacular visions. Judging from surviving evidence and related works, it is likely that these enormous figures smiled down at the Buddhists beneath them with a calm benevolence.

The issues discussed in this section are not merely abstract questions of belief; they have real and tangible effects. After centuries of slow degradation, the two colossal figures were destroyed in 2001 by the Taliban, the Muslim fundamentalist then in control of Afghanistan. Still, the destruction revealed new evidence about the Buddhas: a reliquary was found, containing balls of ashes and a Buddhist sutra – that is, a key religious text – written on tree-bark, likely placed within the statue as it was being built, 1500 years ago, allowing the figure to serve as a sort of reliquary, like the Great Stupa discussed above.

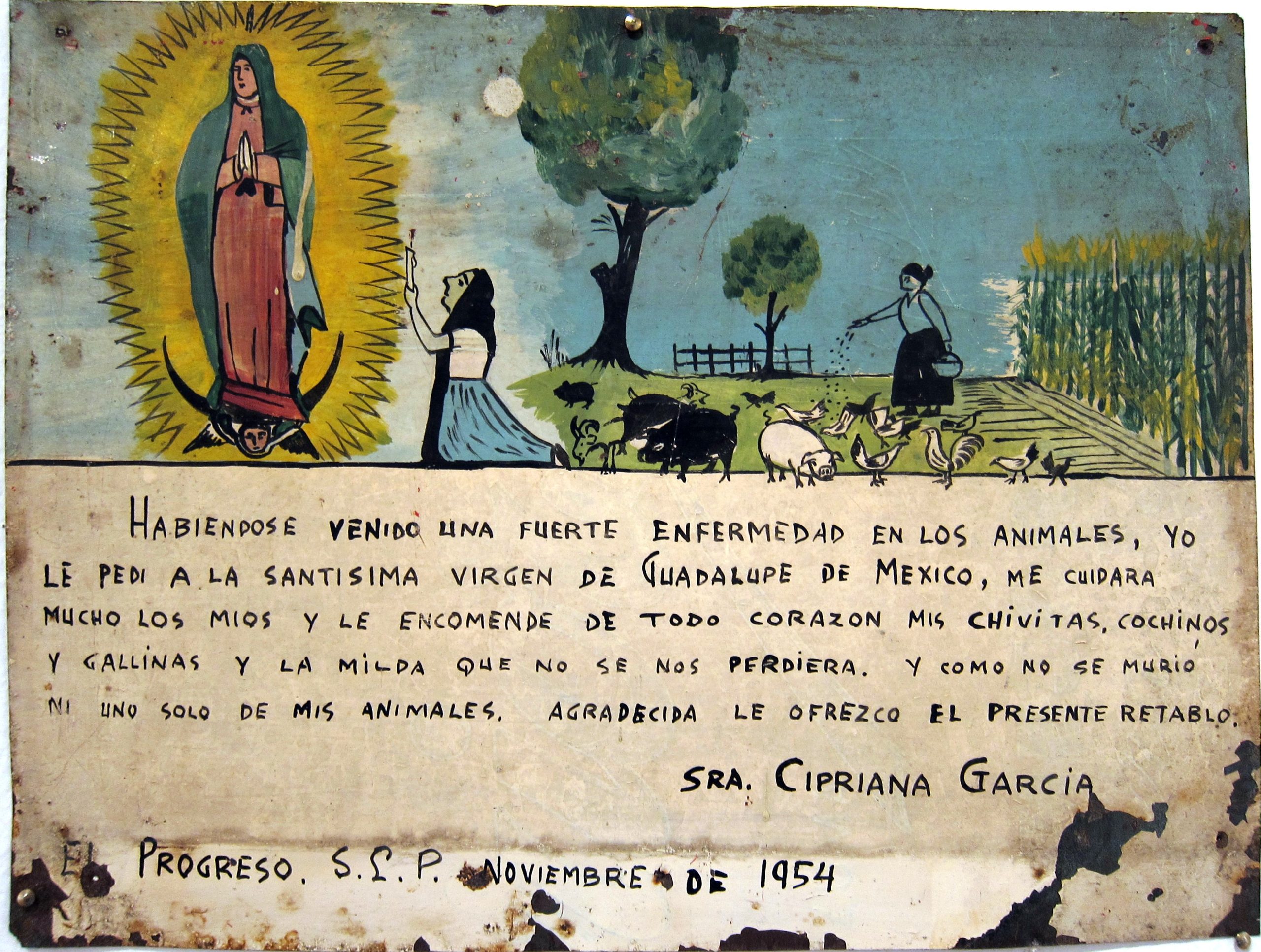

On the other end of the spectrum from the massive Buddhas of Bamiyan, we find moving works of great sincerity, produced in humble scale and format, conveying individual piety and hope. Mexican retablos, also known as ex votos, are small paintings usually made on tin, generally commissioned from artists without formal training, but worshippers sometimes also produce their own. A large number of retablos were produced between 1820 and 1920, and the folk tradition continues today. Such works were for years neglected by scholars before being reappraised by the contemporary art world, where they are now very popular.

Retablos are produced by or for individuals requesting the aid of saints or of the Christian god, and also to give thanks for divine assistance. They tend to refer to very precise events or concerns as in this example, which reads (in translation):

With a serious disease affecting animals all around, I asked the Holy Virgin of Guadalupe to take good care of my animals, and I wholeheartedly entrusted my little goats, pigs and chickens to her, and our crops so we wouldn’t lose them. And since not a single one of my animals died, I gratefully present her with this retable. Mrs. Cipriana Garcia El Progreso, San Luis Potosi. November, 1954.[7]

The text is quite specific in time, place, and content. This is not a generic image celebrating the beneficence of a deity, but a work made by or for a specific individual, in thanks for what is characterized as divine assistance.

Many religious traditions believe in the power of images to affect the lives of people. The retablos, the statues of Buddha and Athena, the yam masks and Tamberan house, these works are not decorative, are not, in our conventional sense really works of art, at all. They are objects of power that are designed to elicit a supernatural response.

Similarly, many of the sculptures of the Kongo are explicitly created to access and influence the spirit world. The nkisi nkonde is among the more visually arresting of these figures. Nkisi are figures created as hosts for magical powers, carved by sculptors and then ritually empowered by a diviner or other ritual conductor who would place bilongo – medicinal materials – within them. In this example, the hollow space in the chest was for the bilongo.

The figure is powerfully aggressive; his torso leans forward, his parted lips show sharpened teeth, and his placement of his hands on his hips and his elbows out all convey his forceful nature. The nails driven into the four foot tall figure attest to the nkisi nkonde’s use: whenever its help is needed, a nail is driven into it, bringing it sharply to attention. The figure would be called upon to preside over treaties, track down criminals, and even assist the sick. The large number of nails protruding from the figure demonstrates its frequent use, and therefore the faith placed in it.

There are works that exist in between the grand works produced to convey the devotion of a community, such as the Great Stupa, Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Tamberan House, Great Mosque of Córdoba, Parthenon, and Colossal Buddhas, and the magical, protective and invocatory works like the nkisi nkonde, retablo and yam mask. The majestic moai figures of Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island, ca. 1000-1500 CE), for example, at once embodied the dedication of the community and were created to serve immediate and practical, protective functions. Many of these figures are monumental in scale, with many approximately thirty-five feet tall, and others (including an unfinished example that was found in a quarry) twice that size. Everything about these figures conveys a sense of authority: their large size, their frontal, upright poses, fancy headdress or hair (the pukau topknot of red scoria stone) and their direct stares out of highly exaggerated and enlarged eyes made of white coral and stone that enliven their faces. They are also placed atop stone altars (called ahu), elevating them above the viewer yet further and making them sacred.

Scholars generally believe that these figures were intended to represent important ancestors, dead chiefs whose names they bore and who would serve as central figures for the community. The larger the figure is, the greater the status of the community. Almost all of the moai are carved out of soft volcanic tufa, but one example survives in basalt, a much harder and therefore much more durable stone.

This four and a half ton sculpture was kept in a stone house in Orongo, the sacred center of Rapa Nui, and was one of only a few to survive a wave of destruction during a series of conflicts that seem to have resulted from the islanders’ overuse of the available resources. Rapa Nui is the most remote island in the world, so the original inhabitants were highly limited in their resources, unable to import anything. If these figures were, indeed, seen as protective ancestral spirits, it makes sense that, in wars between tribes, the moai were attacked as if living beings. Works of art are not always seen as mere objects; for many cultures they have been and continue to be seen as active, living, powerful beings.

CONCLUSION

The grand sculptures of gods and majestic temples discussed in this section are a long way from Chauvet Cave in time and conception. Still, there is an affinity between all of the images in this chapter. The people who commissioned and created and used them might have been and might continue to be sharply at odds with one another, as the religions that inspired them often see themselves as mutually exclusive. The works themselves similarly conflict with one another, with naturalistic idols juxtaposed with highly stylized images for teaching, beside aniconic works rejecting all imagery. Grand monuments are adjacent to modest efforts. Wherever you travel, whatever cultures you confront, whatever museums you visit, you will find works inspired by the religions of the world, present and past, monotheistic and polytheistic, welcoming or intentionally exclusive. But all of these work, ultimately, have their roots in the caves, painted tens of thousands of years ago, where our subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens, first worked out some of the visual tools that we can use to represent the supernatural, and our desires for it.

Spotlight Image III:

Statue of Mother Goddess Coatlicue, Aztec, Mexico, 1487-1520 CE

VIEWING QUESTIONS

What are the main compositional principles used to design the figure?

What does the material used suggest?

How is symmetry used?

Is the work naturalistic?

Is the work idealized?

What can we tell about the figure and the culture that produced it without any contextual information? Be sure to bear in mind cultural beliefs and biases that you might bring to the work!

Media Attributions

- Chauvet Cave (Ardèdeche, France). Photo by Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0.

- Chauvet Cave (Detail of horses). (Ardèdeche, France). Photo by Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0.

- Chauvet Cave (possible wooly mammoth). (Ardèdeche, France). Photo by Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0.

- Chauvet Cave (Detail of Rhinoceros), (Ardèdeche, France). Photo by Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0.

- Chauvet Cave (Bear Skull), (Ardèdeche, France). Photo by Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0.

- Chauvet Cave (Detail of Rhinoceros), (Ardèdeche, France). Photo by Claude Valette, CC BY-ND 2.0.

- Naiku (Ise, Japan). Photo by N. Yotarou, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Diagram of Shinto Shrine (Ise, Japan). Image by Mari H.

- Great Stupa, Madhya Pradesh (Sanchi, India). Photo by Raveesh Vyas, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Great Stupa, Madhya Pradesh (Detail of East Gate), (Sanchi, India). Photo by Biswas Purba, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Great Stupa, Madhya Pradesh (Detail of Yakshi), (Sanchi, India). Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0.

- Great Stupa, Madhya Pradesh (Detail of Footprints), (Sanchi, India). Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0.

- Artemision Zeus (Detail of Face), bronze, ca. 460 B.C.E. (National Archaeological Museum, Athens). Photo by dynamosquito, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Artemision Zeus (Detail of Face), bronze, ca. 460 B.C.E. (National Archaeological Museum, Athens). Photo by dynamosquito, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- The Good Shepherd, Asia Minor, 280-290. Photo: Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0 1.0.

- Gislebertus, Last Judgment, Tympanun, Cathedral of St. Lazare, c.1130-46 (Atune, France). Photo by Jim Forest, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

- Gislebertus, The Temptation of Eve, ca. 1130 (Museé Rolin, Atune). Photo by Morio60, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Detail of Gislebertus, The Temptation of Eve, ca. 1130 (Museé Rolin, Atune). Photo by Jacquym, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Detail of claw of the devil, Gislebertus, The Temptation of Eve, ca. 1130 (Museé Rolin, Atune). Photo by Morio60, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Abelam, Yam Mask, fiber, paint, twentieth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Photo by Shooting Brooklyn, CC BY-SA 2.5.

- Abelam, Tamberan House (Museum der Kulturen Basel, Basel). Photo by Ismoon, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Interior, Tamberan House, in Tongajan (aka Tongijamb or Tongajamb) village on the Sepik River, New Guinea. Photo: Carsten ten Brink, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Cordoba – 39

- Great Mosque of Córdoba (Plan), 786-1600, (Córdoba, Spain). Image by Ali Eminov, CC BY-NC 2.0.

- Great Mosque of Córdoba (Interior), 786, (Córdoba, Spain). Photo by Richard Mortel, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Great Mosque of Córdoba (Interior), 786, (Córdoba, Spain). Photo by Asa Simon Mittman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Great Mosque of Córdoba (arches in front of Mihrab), 10th century, (Córdoba, Spain). Photo by Asa Simon Mittman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Great Mosque of Córdoba (dome in front of Mihrab), 10th century, (Córdoba, Spain). Photo by Asa Simon Mittman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Great Mosque of Córdoba (Detail of Mihrab), 786 (Córdoba, Spain). Photo by Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0.

- Dura-Europos Synagogue (West Wall), ca. 245 (Syria). Photo by Sodabottle, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- The Ark and the Temple of Dagon, ca. 245 (Dura-Europos, Syria). Photo: Public Domain.

- Parthenon, ca. 447 (Athens, Greece). Photo by Mr. G’s Travels, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Alan LeQuire, Recreation of Athena Parthenos, 1982 (Nashville, Tennessee). Photo by Mobilus in Mobili, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Colossal Statues of Buddha, second-fourth century (Bamiyan, Afghanistan). Photo by UNESCO/A Lezine and Carl Montgomery, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Destruction of Colossal Statues of Buddha, 2001 (Bamiyan, Afghanistan). Photo by Christian Frei Switzerland, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Angélica Portales, Ex-voto of Mrs. Cipriana Garcia El Progreso, San Luis Potosi. November, 1954. Photo: Angélica Portales, 2012, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

- Nkisi N’kondi, wood, resin, iron, ceramic, plant fiber, textile, pigment, nineteenth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Photo: Public Domain.

- Moai Figure, ca. 1000-1500 (Ahu Nau Nau, Easter Island). Photo by Márcio Cabral de Moura, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

- Hoa Hakananai’a, basalt, ca. 1100-1200 (British Museum, London). Photo by James Miles, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Coatlicue, basalt, ca. 1500 (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City). Photo by Xuan Che, CC BY 2.0.

- Coatlicue (Side View), basalt, ca. 1500 (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City). Photo by David Cabrera, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Christine Desdemaines-Hugon, Stepping-Stones: A Journey through the Ice Age Caves of the Dordogne (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 17. ↵

- Nuha N. N. Khoury, “The Meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the Tenth Century,” Muqarnas 13 (1996): 80-98, 86. ↵

- Nuha N. N. Khoury, “The Meaning of the Great Mosque of Cordoba in the Tenth Century,” Muqarnas 13 (1996): 80-98, 88. ↵

- Exodus 20:4-6, New International Version. ↵

- Qur’an, 6:103 and 14:35. ↵

- Exodus 20:4-6, New International Version. ↵

- Translation by Angélica Portales: https://www.flickr.com/photos/frozen-in-time/7076400521/. ↵

Paying for the creation of works of art; a person who provides patronage is called a patron

of any culture, before (or without) a written form of language

concentration of objects or details

The use of similar elements so that all the parts of a work fit together well

The relationship of parts of an image to the image as a whole, or to something in the world outside of the image, for example, the size of the figure of a king in an image as compared to the size of the figure of his servant in the same image, or the size of a statue of the king as compared to the size of an actual person

in art, a system to create an illusion of three-dimensional space in a two-dimensional medium

The use of darker colors or lines to create the illusion of shadows

Depth, real or represented, as well as the general area within a work

The property of a two-dimensional form, usually defined by a line around it

lines that define shapes

the time period after the development of writing

the circumstances around a work, idea, event, etc.

From the Greek words for “old stone,” the period of prehistory from approximately 2.6 million years ago (when the earliest stone tools were developed by our evolutionary ancestors) until about 10,000 years ago, ending along with the last ice age and accompanied by the development of agriculture in the Neolithic (“new stone”) period.

From the Greek words for “new stone,” the period of prehistory following the Paleolithic, and running from the end of the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago, and accompanied by the development of agriculture

Making an image look like the “real world”

Deviations from the appearance of the natural world, simplifications or alterations of it for effect

religion practice in which shamans are believed to connect with the spirit world in order to learn about or have an influence on this world

believing that inanimate elements of the world and universe, like objects and plants, have spirits or souls

related to totems, objects of power; also, symbolic of qualities or concepts

definition

a follower of the religion of Buddhism

see "relic"

Literally, "the awakened," the title given to Siddhartha Gautama, founder of Buddhism, a prince you rejected his wealth in favor of a life of simple contemplation aimed at escape from endless cycles of reincarnation and into Nirvana, release from all suffering

In Buddhism, tall stone gateways

travelers whose travels have a religious purpose; often, pilgrims travel to holy sites

being reborn into a new body after death

female benevolent minor deities common in Indian belief and found in both Buddhist and Hindu art

male benevolent minor deities common in Indian belief and found in both Buddhist and Hindu art

Oldest practiced religion in the world, originating in India. Hinduism has tens or even hundreds of thousands of gods, and no single set of beliefs or laws regarding them, but rather, celebrates pluralism.

believing in multiple gods

an image designed to be inhabited by a deity

Of works of art, to display naturalism, that is, to look like the actual world

represented not as is, but according to a culture's belief about what the ideal form would be, eg. the form of the human body. Ideals change over time, and vary from culture to culture.

Usually used to describe bilateral symmetry, which is a mirroring of two halves of a work, or radial symmetry, where an image is symmetrical around a central point or axis, like a sunflower viewed head-on

a fusion of the cultures of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, led by Roman scholars from the first century CE through the third century CE.

all the deities of a people or religion; literally "all gods"

a semicircular sculptural panel over a doorway

In some way or ways deviating from or ignoring the appearance of the natural world, simplifying or altering it for effect

a full-body halo

A type of scale based on relative importance, in which more important figures are represented as larger than less important figures around them

a horizontal member placed on top of two vertical posts, as in rectangular doorways

the study of the origins of the universe

believing in one deity

the monotheistic god of Judaism, also shared by Christianity and Islam

a story

Formal, often elaborate ceremonial clothing

having human qualities

resembling male genitals

Repeating an object or element evenly throughout a work or a part of a work

a space in religious architecture, generally large and open, where worshippers congregate for prayer

in architecture, a cylindrical, vertical member, usually supporting a lintel or arch

artistic or architectural elements reused from previous works, often displayed clearly in order to convey political or religious conquest

Germanic peoples of Spain, from the late classical through the early medieval periods

In Catholicism and Anglicanism, a church housing the bishop's "cathedra," the throne that signifies their authority, and serves as the administrative center of a see (the area ruled by a bishop)

architectural elements consisting of a weight-bearing, arched roof, usually in stone

arches topped by arches

architectural element at the top of a column or pillar that generally widens its form in order to help support a lintel or arch above

in Islam, a niche in the wall of a mosque that faces toward the Ka'ba in Mecca and therefore indicates the direction of prayer

resembling plants, esp. plant leaves and vines

a rounded architectural feature shaped like half of a sphere

columns partially embedded in a wall

characterized by straight lines and smooth curves of the sort found in mathematical geometry

The holy book of Islam

The male head of a family or tribe, especially used to describe biblical figures

avoiding the creation and use of figural images, especially of deities or other religious figures

a person commissioning a work of art to be made and paying for it

the practice of avoiding the creation or use of images, esp. figural images and images of deities

see Fresco

the triangular section, often filled with sculpture, at the top of the facade of a building, esp. an ancient Greek temple

three-dimensional space or shape

the region extending from Turkey in the east to Israel in the west, and centered on a series of civilizations that flourished in what are now Iran and Iraq from the fourth through the first millennium BCE

covered in gold and ivory

the raised, sacred precinct of ancient Athens

religious text in Buddhism and Jainism; also religious law in Hinduism

a container for relics, which are the remains of a holy figure, or items of importance to them

large, massive

showing the front of a figure or object as fully facing the picture plane