3 Nature

How and Why Do Artists Present the World Around Us?

The natural world appears as a major theme in the visual arts from the very earliest images, such as the cave paintings discussed in the Religion chapter. The representation of the world around us is found, in various degrees and various forms, in all periods and regions. However, representations of the natural world are, themselves, never natural. That is, there is no way to merely present the natural world “as it really is,” without this being influenced by the culture in which it was produced. Our cultures impact our perceptions of everything around us, and dictate the ways that we construct our images. Even a photograph of a landscape – perhaps the form that gives the greatest sense of accurate depiction of the world – is based on ideas the photographer brings to bear on that landscape, as well as the technologies used to generate the image.

In this chapter, we look at a wide range of images depicting nature, with an emphasis on images of the land, and its flora and fauna. Some will celebrate the glories of nature, but others will present the natural world as a place of danger and strife. Still others will use the natural world as a metaphor for other concerns, embodying humanity or set in opposition to it.

These images are connected to those in many other chapters. Nature and the natural world are important elements of religious imagery, of images of human body, of gods and of nations. The image of Zeus in the Religion chapter, for example, might be discussed in regard to religion (he is a god), the natural world (an embodiment of thunder), power (he is in the process of using divine might to destroy someone), community (in Ancient Greece, religion was used to bind communities together around the worship of local versions of gods), violence (his action is one of violence), and so on. Most works of art contain many themes, and much of the most interesting work they do comes from the interplay between them.

SPOTLIGHT IMAGE I

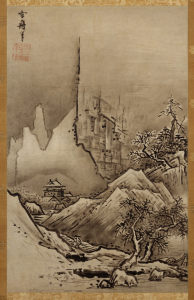

Sesshū Tōyō, Winter Landscape, Kyushu, Japan, 1470s CE

VIEWING QUESTIONS

- How has the artist used contrast to create a mood?

- How has the artist used line to intensify the mood?

- What sort of balance does the image have and how does this affect the image?

- What is the role of the small figure on the steps, near the base of the image?

INTRODUCTION: Sumi-e Painting

Sesshū Tōyō, like most Zen Buddhist monks, practiced the art of sumi-e – black ink painting. The ink is made by burning pine twigs, collecting the soot, and mixing it with resin. This is made into a flat stick. The stick is then rubbed in a small pool of water in an inkstone. The inkstone has a shallow slope to it, so that the ink can be built up on the slope. By mixing in more or less ink with the water, the artist creates the desired value. Sumi-e painting was popular among Zen monks because of its rapidity. The most famous works in the medium are not slowly and laboriously produced, but rather, rapidly sketched out with quick and fluid brushstrokes. Artists often aim for economy of strokes – they try to produce their image with as few strokes as possible, striking for the heart of the image rather than fussing about the details of its outward form. Since Zen Buddhists believe that Enlightenment can strike anyone at any time and with great suddenness, the form suits the belief.

VISUAL ELEMENTS: A Cold, Brittle Day

Sesshū Tōyō’s Winter Landscape (1470s) is a powerful image. The painter manipulates the visual elements with great care and precision in order to create a mood. Since the artist restricted himself to the black sumi ink, the painting is necessarily only in shades of grey. Still, he uses it to with fairly high contrast, so that the darkest brushstrokes are very far in value from the smattering of white areas that result from Sesshū’s decision to leave them unpainted. This high contrast emphasizes the hard feeling of the work, the cold, harsh, brittle sense of winter. Most of the contour lines used to define the outlines of the forms – the hills, temple, trees, and the human figure – are heavy and dark. An image of a snowy landscape might be shown as soft and picturesque, with all the edges blurred gently by the muting effect of the falling snow, but that is the perspective we have of the cold while sitting at the fireside. This image, on the other hand, conveys the sense that we are out in the cold. The landscape is a hard, icy mountain ridge, rather than a soft, snowy wood.

Still, this is hardly a black-and-white image. Instead, Sesshū has made use of a range of values, exploiting the middle grays to build up the weight of winter. The heavy, leaden sky hangs ponderously above. The snow-capped hills turn slushy and dim toward their bases. The only white sections are those around the tree branches, giving the sense that they are covered in snow.

The use of line works together with the contrast in Winter Landscape. The majority of the lines are choppy and jagged. In a depiction of the natural world, we might expect to see more use of organic, curvilinear lines. However, Sesshū constructs the trees, hills, and mountains almost exclusively out of short, straight lines of varying thickness and value. In addition, most of these lines are set at sharp diagonals, with those of the hills almost all at forty-five degrees. This gives the work a sense of energy, though since the lines are set in opposition to one another, with some slanting to the right and others to the left, this energy is pent up, unable to escape in any particular direction.

One line, though, dominates the entire composition: the curious heavy, thick, dark line that runs vertically down the image, just left of center. It slashes downward like a bolt of lightening, jogging briefly left and then slanting sharply off to the right. The space to the right of it is filled with a spiky grid composed of short lines that are mostly horizontal and vertical. These do not seem to be quite representational – what would they depict? Rather, they intensify the crystalline tone of icy winter. For that matter, what is that dominant line? Is it, perhaps, the edge of an overhanging cliff, threatening the little Buddhist monastery crouching beneath it? In that case, the upper portions must be shrouded in mist, since the form simply fades gently away as we move up the painting. Or perhaps it, too, is not really representational at all, not presenting any element of the natural world but, instead, creating a mood.

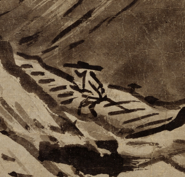

We identify with the small figure who trudges wearily up the long flight of steps, leaning forward into the climb and perhaps into a cold wind, his shoulders hunched up under his broad-brimmed hat. This figure is created through a series of short, quick, straight lines. Sesshū’s economy is impressive. With only a few brushstrokes, he creates not only form but also feeling and mood.

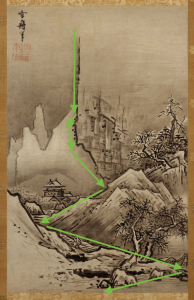

Sesshū’s careful construction of balance is much in keeping with his crisp use of contrast and line. The image is not symmetrical – the two halves do not mirror one another even loosely. However, it has a dynamic, asymmetrical balance. Neither side of the image has greater visual weight to it. Sesshū uses a few techniques to achieve this, foremost among them emphasis.

In this case, emphasis is created through the visual elements discussed above, contrast and line, as well as through the use of concentrated detail. There is more detail on the right side of the painting, particularly in the knotty branches of the bare trees clinging to the rocks. This detail is the result of the sharp, prickly lines that catch our eye, picked out through high contrast with the white around them. On the left, though, the shapes are larger, more open, and brighter. These serve to isolate and thereby emphasize the small series of buildings in their midst. Our eyes therefore bounce back and forth across this image.

The great vertical slash discussed above also works to establish this dynamic balance. It starts almost at the top edge of the image, slightly to the left of center. An artist seeking a more static, symmetrical image might have put it right down the center of the image. However, the line maintains the asymmetrical balance by cutting back to the right and passing through the center of the image. As we follow it downward, it moves to the right until it runs perpendicularly into the sloping hillside, which in turn carries our eyes down and to the left, and into another series of diagonal lines that move us further down and back to the right, to where the figure has moored his small boat. The line of the large boulders in turn pushes our eye back to toward the left, ending just about in the center of the image. This painting, despite its frigidness and balance, is a restless composition.

CULTURAL CONTEXT: Zen Painting

Zen Buddhism – developed by Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan), a Persian or Indian Buddhist who traveled to China – took root in Japan in the twelfth century. Buddhists seek Enlightenment, which leads to Nirvana, a peaceful escape from a cycle of reincarnation (rebirth) into the world of suffering. Bodhidharma believed that Enlightenment could be achieved through concentrated meditation, rather than the complex rituals practiced by some other Buddhist sects. A crucial element of Zen Buddhism is the belief that Enlightenment can strike a person at any point, and this led to the establishment of practices considered more likely to bring it about, including some that relied on interaction with the natural world. Zen monks were encouraged to wander the countryside, taking solitary journeys to remote landscapes in order to contemplate them. In the words of Dong Qichang, a major painter of the seventeenth century whom many tried to imitate for centuries, “Read ten thousand books, and walk ten thousand miles.” That is, study the works of great masters, and study the works of nature. Many Zen ink paintings were produced not in an artist’s studio but in the wilderness. An epitaph for the early master Ni Zan (fourteenth century), tells us:

in his late years, he became quieter and more withdrawn than ever. Having lost or given away everything he ever owned, he did his best to forget his worries … He roamed the lakes and mountains, leading a recluse’s life.[1]

In a poem written at the top of his painting of Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu (1372), Ni Zan writes:

We watch the clouds and daub with our brushes

We drink wine and write poems.

The joyous feelings of this day

Will linger long after we have parted.[2]

Perhaps the most important concept for Zen artists was wabi – the appreciation of a simple, even austere lifestyle that was reflected in art. Wabi has had a strong impact on Japanese culture that continues today, and is perhaps most familiar in the form of the Japanese Tea Ceremony.

Zen monks were allowed to engage in more worldly activities than some other Buddhist monks, including art making. Their paintings were designed to encourage a deeper experience of nature, and to help convey that experience to the viewers. Their purpose is not to accurately and precisely record the appearance of the landscape, but to capture the feeling of a person gazing upon it. Sumi-e painting, practiced with rapid, intuitive brushwork, was perhaps the art form most well suited to this goal. Sesshū excelled at this, making works that are not mere representations of the landscape but rather, images that inspire feelings as much by the way the scene is painted as by the content of that scene.

Here again, the basic tenets of Buddhism help us understand the painting further. Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama (ca. 566-480 BCE), an Indian prince who renounced his decadent lifestyle in favor of a life of meditation and simplicity. Gautama was sequestered in his royal palace, rarely venturing outside. On one excursion, though, he encountered the Four Sights: an old man, a sick man, a corpse and an ascetic – a person who intentionally lives a simple or even harsh life, usually to achieve spiritual goals. This led him to formulate the Four Noble Truths:

Life is suffering

Suffering is caused by desire of worldly things and goals

Desire can be eliminated

The Noble Eightfold Path is the route to ending desire and thereby ending suffering.

The Noble Eightfold Path, in turn, is:

Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

This path is designed to guide the Buddhist toward moral conduct, meditation, wisdom, and, ultimately, enlightenment.

In Sesshū’s Winter Landscape, we can see these principles reflected. The landscape implies the suffering at the core of life, but the long staircase presents the noble path of right living, leading ultimately to the sanctuary of the Buddhist monastery, seeming to represent in this image not merely the immediate escape from the suffering of the traveler in the frigid world but also perhaps implying the greater escape from the entire cycle of worldly suffering: Nirvana. In this case, the entire image becomes a metaphor for the basic beliefs of Buddhism. All of Sesshū’s careful control of the visual elements work to intensify the message that Buddhism is the path to release from the suffering represented by the world. Here, while the image seems at first glance to be about the natural world, in fact nature is being used as a metaphor for all elements of our world, natural and human.

Comparisons and Connections I: Nature as Harsh, Nature as Beautiful

Violent Nature

In emphasizing the difficult or even dangerous elements of the natural world, Sesshū Tōyō was participating in the one of the most ancient of artistic traditions. A wall painting at Çatalhöyük, Turkey (ca. 6150 BCE) is often cited as the earliest landscape – that is, an image where the main subject is the natural world, itself, rather than people or other figures doing something in that landscape. While the subject is not certain, it has been interpreted as presenting an image of an exploding volcano. Çatalhöyük is among the earliest surviving cities, and is the largest Neolithic city to have been found, originally housing as many as 10,000 people, actively engaged in trade for daily and luxury materials. Several of the buildings have wall paintings showing conflicts with the natural world. If this painting does show a volcano, then it depicts what is among the more spectacularly violent events in nature. An event of this nature would certainly capture the attention of ancient civilizations, as it captures ours, though they would likely have interpreted it through a different view of the world.

A brief look at Çatalhöyük’s overall design reveals much about this culture’s view of nature. Whereas we tend to pay a premium for homes and offices with large windows looking out onto landscapes, few of homes and other structures found by archeologists at Çatalhöyük have windows that look outward from the city. This is a society more concerned with protection from the elements than with pretty views. This should not be surprising. The natural world was – and remains – a site of real danger. Here, the danger is of cataclysm rather than of grinding suffering, as in Sesshū’s work.

In the wall painting, we see what appears to be the city spread out as if in a plan, with the wobbly, irregular rectangles representing structures. The lack of streets between them reflects the actual plan of the city. The buildings all adjoined one another, and some were only accessible through holes in the roofs. Towering over the city is a great volcano, depicted in bright orange, arguably based on Hasan Dag, a nearby mountain with two peaks.

Or is it? It has also been suggested that the image does not show a volcano and a city plan but rather, a leopard skin over geometric patterning. While this is a completely different – but also plausible – reading of an unclear, prehistoric image, it also points toward the dangers of the natural world, and the implicit competition between people and their environment. The leopard was a hunting competitor, as it killed the same wild goats hunted by the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük. In either case, then, this ancient image projects a relationship between the inhabitants and the natural world outside the perimeter of their city. Really, we do not have to choose; it could be one or the other, or even could be an amalgamation of both, representing these two natural forces in a single image. With prehistoric art – as with all art – we rarely have final and absolute answers.

In the next image, Joseph Mallord William Turner (English, died 1851) presents the natural world not merely as hard and challenging, as Sesshū does, and as in the image from Çatalhöyük. Nor does Turner make the violence something distant and without clear victims, as Sesshu does. Instead, he presents nature as a consummately terrifying, all-powerful entity, vastly overwhelming the small human figures lost within its rages. In his Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On (“The Slave Ship”) (1840), Turner uses energetic, visible brushstrokes, breaking up the forms and thereby intensifying the sense of chaos. There is nothing quite clear, here; everything seems to be in churning motion. Even the sun, burning through the clouds, does not seem a positive force. Rather, as the most brilliant white, the brightest value in the image, it seems a sharp, almost painful cut, just to the right of the center of the image. In this way, it recalls the vertical slash just off-center to the left in Sesshū’s landscape.

The color palette here is generally warm, but this does not lend the image a cheerful tone. Instead, the reds, oranges and yellows are the shades of blood and bruises. This is all the more disturbing in a seascape, where we might justly expect a cool, gentle image of blue, greens, and whites. It is as if the violent death of the enslaved cargo has been inscribed across the whole of the sea and sky. In the lower right hand corner, great, nightmarish fish rises to the surface in a feeding frenzy.

This painting was based on an account in Thomas Clarkson’s The History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1783), recounting an actual event in which, it seems, the captain of a ship caught in a typhoon had his “cargo” of enslaved people thrown overboard, still shackled together, in order to be able to get a reimbursement from his insurance company for their loss at sea. Just to the left of center, to a degree balancing out the blazing sun, are the hands of the drowning figures, outstretched dramatically in a last, failed, futile effort to cling to the surface, and to life. The oversized black chains, emphasized in a sort of hieratic scale, stand out in the foreground, implausibly but powerfully remaining afloat in the turbid sea. This, of course, would not happen in the real world, where iron manacles would plunge downward immediately, pulling those they bind down with this. Here, then, the artist is choosing symbolic meaning and emotional effect over strict naturalism.

Albert Pinkham Ryder’s seascapes are, if anything, even more intense images of the turbulent violence of the sea. For Ryder, though, the natural world is more clearly presented as a tool of divine retribution. His illustration of the story of Jonah (ca. 1885) is a tumultuous image, mixing biblical and literary imagery with a depiction of the natural world in order to create a terrifying scene. Largely forgotten today, when it was first displayed this painting was hailed as “the greatest art event of the year as far as our native workmen are concerned.”[3]

The biblical Book of Jonah tells the story of a man chosen by the Jewish God to preach on distant shores. He is afraid, and so attempts to flee from this task, and from an omniscient and omnipotent – that is, all-knowing and all-powerful – god, by stealing away in the hold of a ship.

As the biblical text reads:

Then the Lord sent a great wind on the sea, and such a violent storm arose that the ship threatened to break up. All the sailors were afraid … But Jonah had gone below deck, where he lay down and fell into a deep sleep … So they asked him, “Tell us, who is responsible for making all this trouble for us? … What have you done?” … The sea was getting rougher and rougher. So they asked him, “What should we do to you to make the sea calm down for us?” “Pick me up and throw me into the sea,” he replied, “and it will become calm. I know that it is my fault that this great storm has come upon you.” … Then they took Jonah and threw him overboard. … Now the Lord provided a huge fish to swallow Jonah, and Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights.[4]

Ryder might have given us the calm sea after the great fish has swallowed Jonah, but instead he presents the moment of highest drama and chaos. The image has no straight lines, nor any that are horizontal or vertical. Everything is churning and tossing at angles. The sea here is as animate a force as the fish, curving toward Jonah from the right edge of the painting.

The boat in the center is much smaller than that described in the Bible, since this one has no deck, and one could not retire below it. It is a little boat, not a substantial ship, and this makes the lives of those in it seem all the more imperiled. The form of the boat, apparently on the verge of capsizing or even of being folded in half by the powerful waves, recalls the form of the whale to the right, as they are the only solid, black shapes in the composition. By bending the hull so dramatically, Ryder has animated the boat, as well, transforming it into a gaping maw, ready to swallow those within it.

There is more, though: The figure in the background is often taken to be God, pursuing Jonah across the sea, but this does not quite fit.

The bearded figure bears wings, which are not part of the iconography – the visual symbols – of the Jewish God. They do, though, suit a figure described in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem, Rime of the Ancient Mariner (first published anonymously in 1798), a poem that directly inspired another of Ryder’s paintings, With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow (ca. 1883).

In Coleridge’s poem, we read:

And now the Storm-Blast came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong:

He struck with o’ertaking wings,

And chased us south along.

The visual elements of With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow serve to highlight those of Jonah. This earlier painting, while also showing a small boat on a dark sea, has a strong horizontal line for the horizon. The waves do toss the light boat about, but the figures do not seem as desperately endangered. Returning to Jonah, we might view the massive, winged figure who seems to be driving the storm as “the Storm-Blast … with o’ertaking wings.” If so, even the storm itself is an animate, personified element in this turbulent image. In Sesshū’s painting, the cold winter seems impersonal, but for Ryder, the storm – sent by God – is quite personal, seeking out Jonah in the hold of the ship. He also presents the great fish, in line with the biblical text, as merely a tool of God, not a normal element of the natural world.

Personified Nature

The power of storms is a popular theme in art. We might also look, for example, to the work of one of the founding members of the influential Centre of Puerto Rican Art. His Temporal (Storm) (1953-1955) is a print based on a popular song about the San Felipe hurricane that inflicted great damage to his native Puerto Rico in 1927. Here, as in the Ryder, the power of the wind is again personified, now into a massive, dark giant glowering over the helpless people below him. Men, women and children, even a naked baby, are all swept up into the storm. The lines convey the great, swirling motion of the hurricane, and the bodies within it seem passive, as inert as rag-dolls.

A moment of high contrast in the print draws our attention to the figure with his arms raised, literally caught in the grip of the storm. The cluttered village to the lower right is also being swept away by the wind, seemingly under the direction of the giant’s extended left hand.

In some cases, granting intention and will to the natural world is not merely a metaphor, as it is for Tufiño, who of course did not really think that the hurricane was a malevolent giant, or Sesshū, who used it to convey the idea of all worldly suffering. In the figure of Zeus in the Religions chapter, the power of the lightning is literally embodied in the powerful, muscular body of the god, and his intentions guide its direction. Still, the impersonal quality of natural violence is reflected in his impassive expression.

Natural elements and forces need not be conceived of as harmful, though, to be associated with deities. In the civilization of Teotihuacan, a Mesoamerican group justly celebrated for its massive pyramids and other works of art and architecture built around the first century CE, we see the natural cycles of the seasons constructed as deities. The city still bears the name it was given by the Aztecs, meaning “The Gathering Place of the Gods,” as they believed it to be (and some of their descendants still maintain it to be) where the gods gathered to create the universe. On the exterior of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, according to some theories, the natural cycle of dry and rainy seasons were depicted as two deities, the Feathered Serpent, known to the later Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl, and the goggle-eyed Storm God. The images here are seen to alternate between the two, implying the cyclical alternation of the seasons. Still, this does not necessarily imply a peaceful, ecological understanding of natural cycles. The Feathered Serpent was associated with the belief that the natural cycles must be maintained with ritual executions.

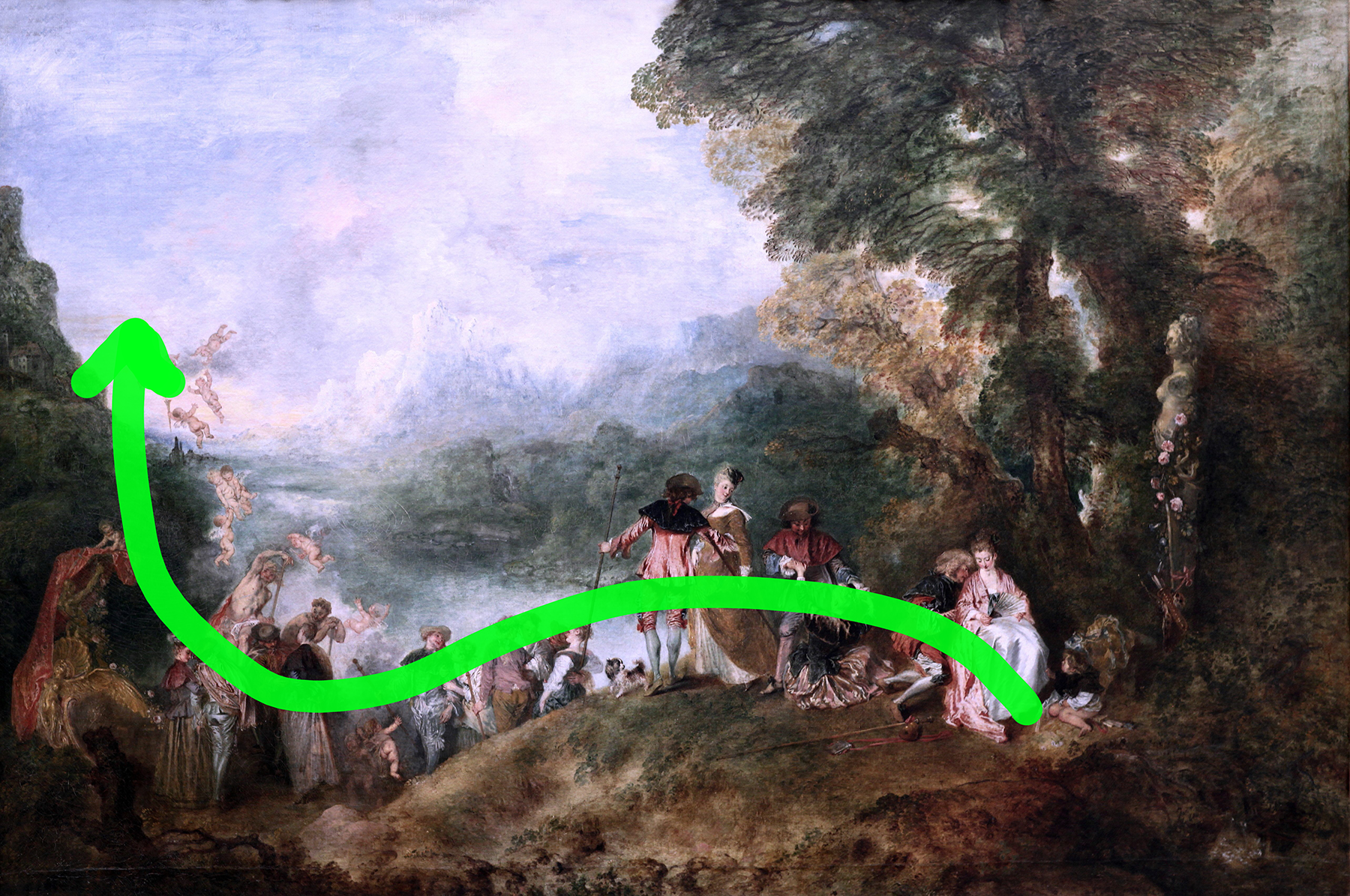

Romantic Nature

Where Sesshū Tōyō, the muralist at Çatalhöyük, Turner, Ryder, and Tufiño all emphasized the harshness and danger of the natural world, Jean-Antoine Watteau instead painted romantic scene of joyous frolicking in the great outdoors. His Le Pélerinage a l’Île de Cithère (The Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera, 1717) depicts a group passing through a lush landscape. The patrons for works like this were wealthy city-dwellers, largely removed from the dangers presented by the natural world.

Watteau was an innovative and experimental Rococo (eighteenth century) painter who began his career by rapidly churning out quick copies of religious paintings and then turned to comic scenes before finally inventing this sort of scene, known as a fête galante – an image of elegant outdoor entertainment. It conveys a frivolous atmosphere of aristocratic ease.

The soft, gossamer brushstrokes suggest that these figures – and the patrons of the work – were not often exposed to the rigors of the natural world, and did not wish to be reminded of them. Here, the beautifully dressed couples, accompanied by putti – the winged cupids floating about – are either heading to or from the mythical island of the goddess Venus, which was therefore the island of love. Their casual, communal stroll is in strong contrast to the uphill struggle of the lone figure of Sesshū’s Winter Landscape. Indeed, everything here is quite at odds with Sesshū’s harsh presentation of nature.

If we follow the procession from left to right, we see that, accompanied by floating cupids symbolizing erotic love, the figures are already pairing off into romantic couples in increasingly compromising positions. At the end of the procession is a statue of Venus, wrapped in a garland of flowers. The rich abundance of nature here echoes the figures’ sexuality. This springtime scene is bursting with life, unlike Sesshū’s hard winter. Where his trees were bare, these erupt in rich greens. Where his lines were crisp and sharp, Watteau’s are soft and blurred. Where his palette was paired down to shades of grey, Watteau’s relies on the springtime pastel tones. The complete ease and safety of these figures is suggested by their spotless clothing. They are richly attired in pale silk, not marred by a speck of dirt or smear of grass stain. These cheerful figures pass through the landscape without being soiled by it.

It is, though, also possible to read this as a somewhat melancholy image of the departure from the island of love. The poses of the figures are ambiguous. For example, is the middle couple of the three in the foreground in the process of sitting down or standing up? The image presents a dream world, but a fleeting one that may already be passing.

If we follow the flow of the figures, guided primarily by Watteau’s use of value, we begin with the figures closest to us, drawn in by the woman’s bright white gown and pink robes. We then follow the brighter tones down and away and then up, as the putti seem to drift off and away, perhaps carrying our prospects for love with them.

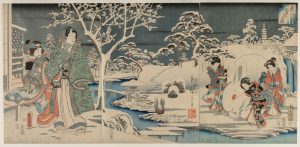

What we as viewers see in and get out of works of art, what our overall experience adds up to, is influence by what we bring to the works. The same is true of our experience of the natural world. Cultures will have differing interpretations of art and of the natural world, but so will individuals within these cultures. In fact, one Japanese artist’s view of nature as a site of adversity (Sesshū’s) is countered by a later Japanese artist who portrays the natural world as a source of pleasure rather than danger: Utagawa (Ando) Hiroshige’s The Snowy Garden from the series Prince Genji of the East (created with Utagawa Kunisada in 1854) presents a winter day as a delight. Hiroshige was born into the samurai class, but gave away his title as head of his clan in order to pursue his artistic career. He achieved great acclaim in his own lifetime, and is particularly renowned for his ability to create atmospheric effects in the medium of woodblock printing. In this scene, the handsome and romantic Prince Genji – known from the Tale of Genji, written by Lady Murasaki Shikiby in the early eleventh century – looks on as three women create a large snow sculpture of a rabbit.

The two Japanese images differ starkly. Sesshū’s painting is all in cold, dreary gray tones, whereas Hiroshige’s print is mostly bright, unsullied white, dotted with the soft pastel colors of the figures’ robes. Here, the leaden sky does not darken the tone of the image, but rather, highlights the brilliance of the snow, and of the equally white figures. The trees, while covered in snow, are mostly evergreens, and seem blanketed rather than shrouded. The lines are mostly softened and round, the edges of all the forms blunted by snow, rather than highlighted by ice. Finally, where Sesshū’s figure was lonely and scantly clad against the cold, Hiroshige’s figures are wrapped in rich, floor-length robes; where the frozen landscape was for Sesshū’s figure a challenge to be overcome, for Genji and the women around him, it is a source of wonder and delight.

SPOTLIGHT IMAGE II

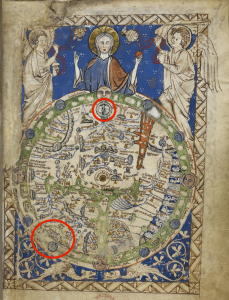

The Psalter Map, England, ca. 1275 CE

VIEWING QUESTIONS

- What is emphasized, and how?

- How is symmetry used?

- How does scale influence the meaning of the work?

- Is the image naturalistic?

INTRODUCTION: A Medieval World View

Medieval Christians believed that the Christian God planned the layout of the world. They therefore saw the natural world not as many modern people do – as a product of natural forces like plate tectonics and volcanic activity – but as the perfect creation of a perfect god. Therefore, all elements of the natural world had great symbolic significance in the Middle Ages (ca. 400-1400 CE). Saint Augustine of Hippo, a highly influential author of the fifth century CE, writes, “The circle of the earth is our great book. In it I read the perfection which is promised in the book of God.” This means that looking closely at the earth could be seen as similar to careful study of the Bible.

Maps like this were not designed for use by travelers – they would not have been very helpful for this – but rather, for contemplation. They present the natural world like a text for us to read. Studying this image should help us to see how great the impact of culture is on our interpretation of the natural world.

VISUAL ELEMENTS: An Ordered World

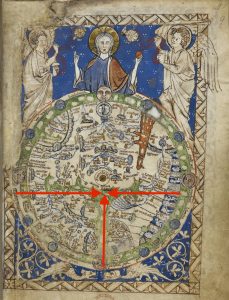

The organization of the Psalter Map is based on several common compositional devices that help viewers know where to look first and identify what is important. Among the more powerful of these is symmetry. This image contains two forms of symmetry, bilateral and radial.

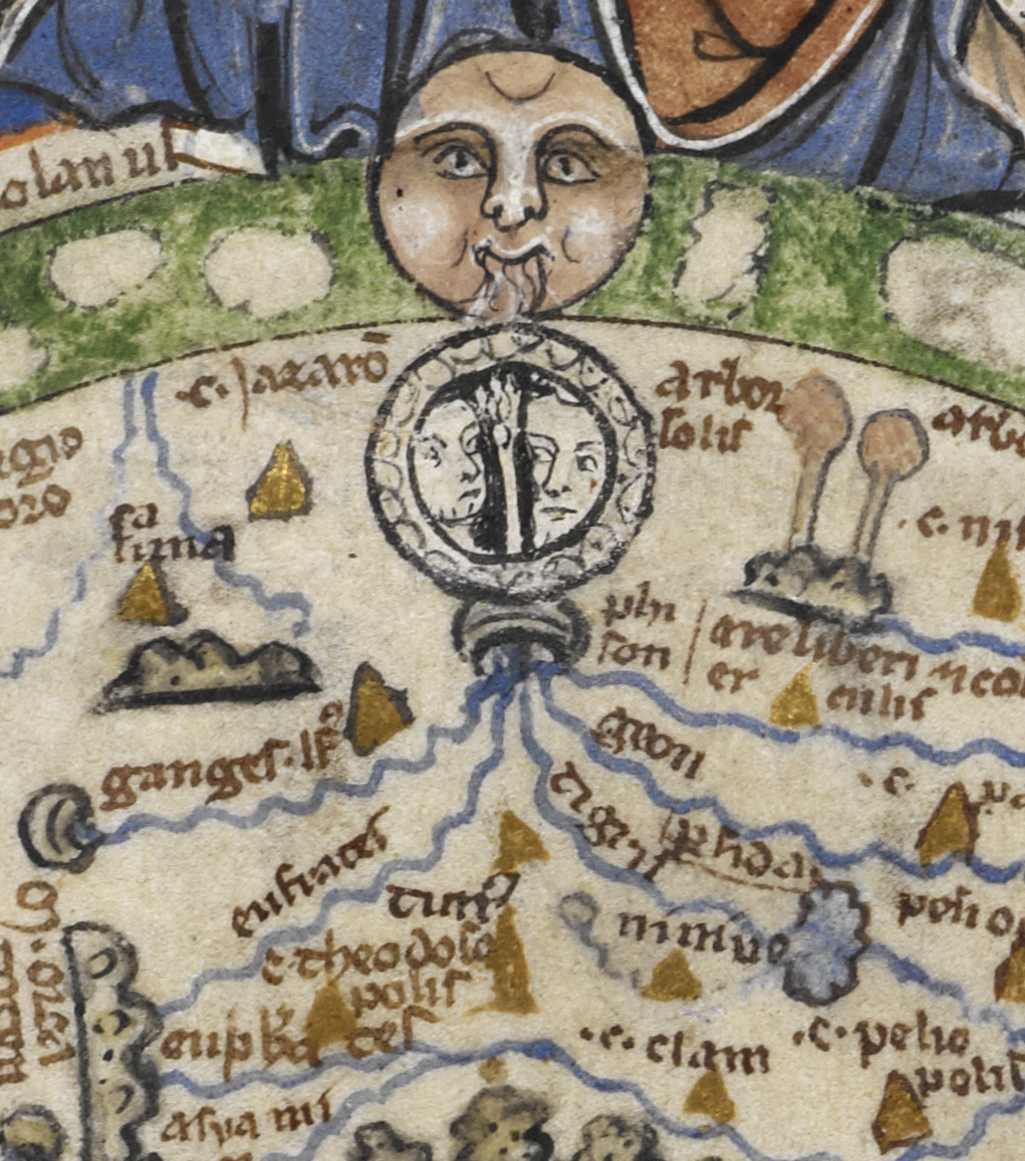

Starting at the top, we find the figure of Jesus in the center, indicating his importance. He seems to be emerging out of the great circle of the world below him. This emphasizes that the world, for this culture, is not a “natural” thing, at all, but a divine creation, intimately connected to its creator. Another thirteenth-century English work even shows us an image of Jesus creating the world by laying it out with a compass, just as the mapmaker of the Psalter Map laid out his small map.

The natural world in the Psalter Map does not look as it does in our modern maps. It is laid out with radial symmetry, emphatically centered on Jerusalem, the city Christians believed to be at the literal and spiritual center of the world.

While the rest of the image of the world is not presented as perfectly symmetrical, major elements balance one another out. In each “corner,” there is a major feature. Moving clockwise from the top-right, we see the reddish-orange Red Sea, the alternating blue and orange cells containing the small white figures, the great complexity of mountains and rivers, and the curving wall and gate. Each of these regions, therefore, has similar visual weight, conveying a sense of radial balance to the world.

The orb of the world is also presented as having a certain bilateral symmetry, matching that of the heavens, depicted above. On either side of Jesus, mirrored angels swing incense burners toward him. While the three figures are not perfectly symmetrical, they are largely so, and this creates a sense of importance and also makes the image appear somewhat still and timeless. Even the incense burners, which are at the top of their arc, seem permanently suspended there.

Below Jesus, at the top of the map itself, is a small black circle, representing the Garden of Eden. This is divided in half by the Tree of Knowledge of the Good and Evil, with Adam and Eve on either side. Radiating out from Eden are five rivers that are also arranged with rough symmetry. Following the central axis downward, we pass through a mountain range with four roughly symmetrical peaks, through a large lake to Jerusalem, and then onward down through the vertical green body of water that is the Mediterranean Sea. Through the use of all of these formal elements, this vision of the natural world as seen from above – the perspective of God – shows the world as far more ordered and less haphazard than we know it to be.

Scale is also vital in conveying importance in this image. The figure of Jesus is somewhat larger in scale than the angels to his sides. More dramatically, though, he is massively oversized in relation to the entire world, displayed below him. It is clear that Jesus is being presented as holding absolute power over the natural world. Indeed, in his left hand is a small red orb with two lines drawn on it.

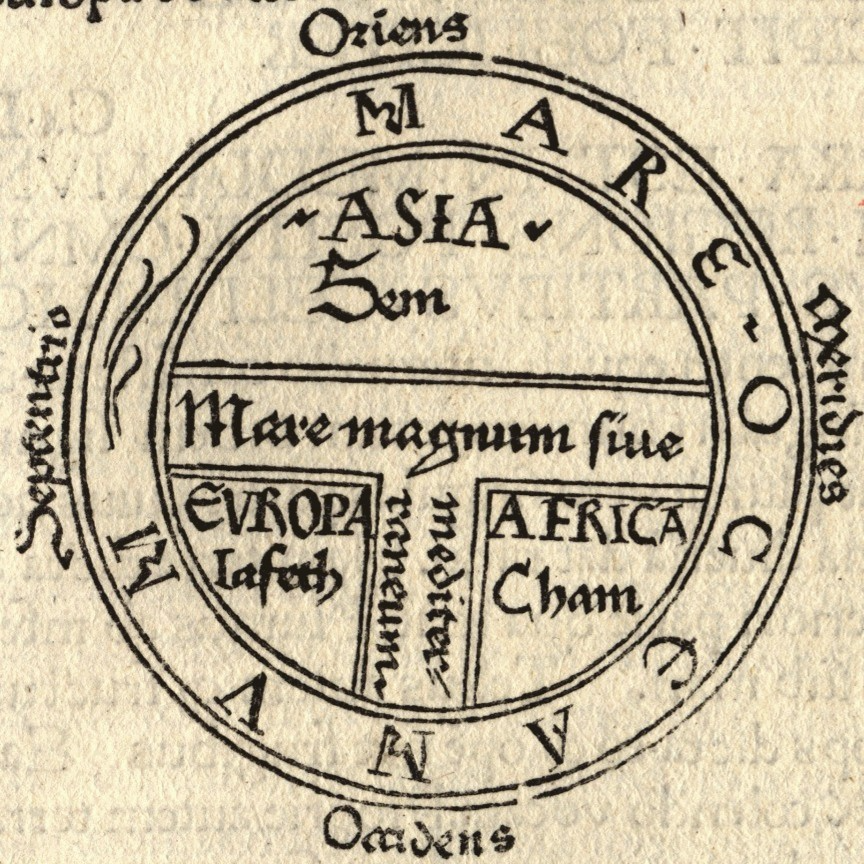

This is a “T-O” map, the most common type in the Middle Ages, when this image was painted. There is a perhaps subtle repetition, here, as the entire map is, in essence, a more complex version of the T-O map. The green Mediterranean makes the vertical line, and the River Don and the Nile form the horizontal arms. In this way, the small red orb parallels the large, detailed image of the world. This repetition is used to further reinforce Jesus’s control of the world he holds so casually in his hand.

CULTURAL CONTEXT: Mapping Religion

Medieval European culture was dominated by a Christian worldview in which the Bible was the highest authority. Many medieval scholars believed that the best of times were in the past, and so they were more inclined to trust ancient texts than they were to believe the evidence of their own experience of the world. The Psalter Map is a good example of an image of the natural world based not on contemporary travels and scientific studies, but on the Bible and other texts.

We therefore see on the Psalter Map, and on a simpler T-O Map, the three continents accounted for in the Bible: Asia, Africa and Europe. Many maps from the period do little but show these continents. We might be surprised to see that Europeans placed Asia at the top of the map, rather than Europe, but medieval Europeans did not think that their own continent was the most important place, since it did not feature significantly in the Bible. Really, the Bible hardly mentions any European locations. Rather, “Asia” – which in ancient and medieval Europe, referred only to the portions of Asia closest to Europe, since the rest was unknown – was the setting for many of the most important Biblical events and sites.

Just below the figure of Jesus, for example, is the Garden of Eden. The Garden was believed to be a real place, the most perfect section of the natural world, located at the eastern edge. In comparison, Britain, where this map was made, is at the bottom corner, tightly pressed in on from all sides. Medieval maps like this are therefore oriented toward the “Orient” (Greek for East), which is therefore placed at the top in order to convey its relative importance.

The map looks like a flat disc, but this is not because people in the Middle Ages thought the world was flat. This is simply not true. While maps like the Psalter Map present the world as a disc, our maps generally show the world as a similarly flat rectangle, which we understand represents the spherical world. They did not, though, know about the other contents. Instead, they assumed that there was nothing but water around the “back” of the world. There were a few early explorations, such as the voyage of the Viking Leif Ericson to “Vinland” – present-day Newfoundland, Canada – around 1000 CE, but their discoveries were not widely known.

This map would be of no use to someone trying to travel from England, where it was made, to Jerusalem at the center, or beyond to the more distant lands of Africa and Asia. What was it for, then? Certain elements suggest that we should read this image of the world symbolically. The puffy-cheeked winds and the reddish Red Sea are just two of many such elements. Jesus’ gesture is also symbolic. He raises his right hand in a traditional symbol of blessing. He might be seen as blessing the world, but since he is looking out at the viewer, he might also be seen as blessing the reader of this Psalter. The Psalter is a volume containing the Book of the Psalms, from the Hebrew Bible, as well as other texts. It was one of the most important books for Christian devotion in the Middle Ages. This map comes at the very beginning of the Psalter, suggesting that the viewer was supposed to approach it with a similar devotion, and to focus careful contemplation on it, just as they were supposed to approach the psalms that follow it.

At the base of the image is a pair of dragon-like monsters. They are, because of their location, contrasted with the images of Jesus and the angels at the top. Just as the images at the top of the map suggest Heaven, these monsters are probably intended to suggest Hell. Their tails turn into vine-like plants that sprout leaves. Since these natural elements are growing out of frightful monsters, they imply the rather negative view that medieval people had of the natural world. While they believed that all the world was created by God, they also thought that it was filled with the traps and snares of the devil. The natural world, with all of its real dangers and its seductions, was to be viewed with great caution, even fear.

The small faces around the edge of the world are representations of another natural force: the winds. With beige faces at the four cardinal directions (North, South, East, and West), and pairs of dusky blue-gray faces in between, they create a consistent pattern pointing inward to the center of the image. They also, though, convey ideas about race commonly held by Christians in medieval Europe. The blue-grey color is one often used in medieval depictions of African and Muslim figures (and especially African Muslims), and is further emphasized by the figures’ hair, which is shown as closely cropped and tightly curling.

These images are often dehumanizing, reinforcing ideas about the fundamental differences between European Christians and other peoples they encountered throughout the world. The use of white faces for the cardinal – that is, the most important – winds and these blue-gray faces for the lesser winds conveys its creator and patron's belief that groups were not only different from one another, but that these differences made groups better or worse than one another, and unsurprisingly, these European Christians placed themselves as the top of this hierarchy. Such views are the backstory to much modern racism.

In a sense, then, the Psalter Map has some common ground with Sesshū Tōyō’s Winter Landscape, as both of these works see the landscape not, in essence, for its “own sake,” but as an object of human contemplation; and both saw this contemplation as a potential route to avoid suffering (reincarnation for the Buddhist, hell for the Christian), and to approach joy (Nirvana for the Buddhist, Heaven for the Christian). The concerns and ideologies of the artists and viewers, then, are written across the landscapes of the natural world.

Comparisons and Connections II: Humans, Animals, and their Place in Nature

A Continuum of Life

While the Psalter Map looks and functions rather differently than current Western maps, it is nonetheless a recognizable part of this tradition. Other images of the land and its contents provide good points for comparison. Aboriginal Australian paintings, for example, might also be considered maps of their landscape, and are similarly symbolic in focus. Indeed, they are more fully symbolic than medieval European maps in that they do not embed the symbolic contents in an oriented diagram of the whole world.

Kumantajayi Long Tjakamarra’s Emu Dreaming (1972) presents a diagrammed landscape with a sinuously curving river at the left, paralleled by the similar form of the snake just to it’s right. Here, as on the Psalter Map, repetition of a form is used to form a conceptual connection between the two elements. This snake is the ancestral snake that created a lake, and so it takes on the watery form of the river.

Near the center of the image is a form that is quite similar to the depiction of Jerusalem at the center of the Psalter Map. Each is a series of concentric circles, giving a sense of power radiating outward from the midpoint. This general form is repeated throughout the image, in a loosely formed pattern. In Emu Dreaming, the form represents a waterhole that is seen as the source of the ancestral emu. The bird footprints that spiral around the waterhole and throughout the image imply the presence of the ancestral emu’s numerous avian descendants. Animals are presented as the most important elements of the land in Tjakamarra’s painting, while they are almost totally absent in the Psalter Map. On the map, the only “animals” present are the dragons that highlight the dangers of nature and, if we look very closely, a gazelle of sorts being ridden by a small figure in the row of monsters at the left edge of the map.

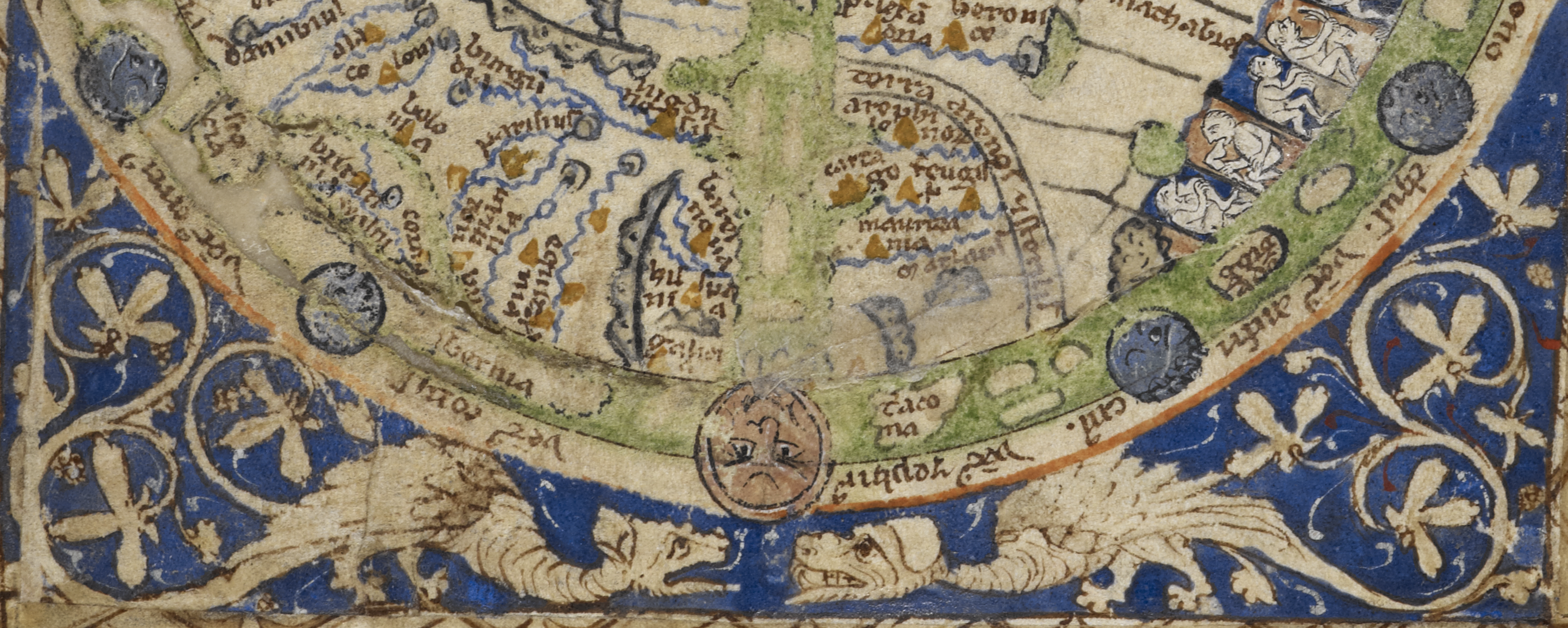

While the Psalter Map ignores or actively avoids images of animals in the landscape, focusing instead on human cities and territories, and Tjakamarra’s painting emphasizes the presence and value of animals, Blake Debassige’s Tree of Life (1982) works to integrate the human and animal into a continuum, symbolized by the tree. This work is also a sort of map, combining traditional Ojibwa (Chippewa) Native American and Christian cosmology, in which the great tree at the center is also the cross of Jesus’ crucifixion. The tree is a vertical axis in the image, representing the connection of the zones of earth, water, and sky. Traditional Ojibwa religion teaches that this axis carries prayers between realms of power, while in Christianity the Cross is a site for devotion and prayer, and so in this work, the gray form at the center serves to embody both ideas. This tree is bursting with life, with foliage, birds, animals, humans, and mythical beings all sprouting from or clinging to its form. The line styles and colors are so consistent throughout the image that all of the elements seem integrated into a single, cohesive system. In the world view presented by this image, Ojibwa and Christian, human and animal, natural and spiritual are all compatible and united, a view quite different from that embodied in the Psalter Map, where walls, mountain ranges, and boundaries, and difference between groups of people, are emphasized.

The Place of Animals

Such harmony is not always the focus of images of human and animal interactions. Artists also work to show the problems that result from sharing the world with other species. Sunaura Taylor has explored the breakdown of the cycles of the natural world in her work on factory farming. Her Chicken Truck (2007) is a large-scale painting that, at over 10 feet wide, presents the viewer with nearly life-sized images of chickens crammed into small crates for transport. Taylor chose to align the crates with the picture plane, so that their fronts seem to be at the surface of the painting. This allowed her to emphasize the grid-like quality of the crates, thereby establishing a regular pattern that highlights the unnatural, mechanized quality of this system of production and consumption. This decision also presses the chickens toward the viewer. They are right in front of us, not deep within illusionistic space, which encourages us to feel closer to them emotionally as well as physically.

This image contrasts sharply with the common images on packages of packed poultry, which show healthy birds roaming through sunlit farmyards, with the ever-present red barn in the background. In Taylor’s painting, the stress is on the conflict between uniformity and regularity, embodied in the crates, and the messy reality of the animals they contain. The crates are composed of rectangular, inorganic shapes, though they do show some bending and breaking, whereas the birds are organic lumps. Taylor uses high contrast between the bright white of the feathers and the inky depths of the truck. There is also strong contrast between the white feathers and the flecks of red throughout. Are these the chickens’ combs and wattles, or are they splashes of blood? Zoom in on the image in the newsletter link above. A close look shows that, due to the painter’s loose, brushy style, we cannot always tell.

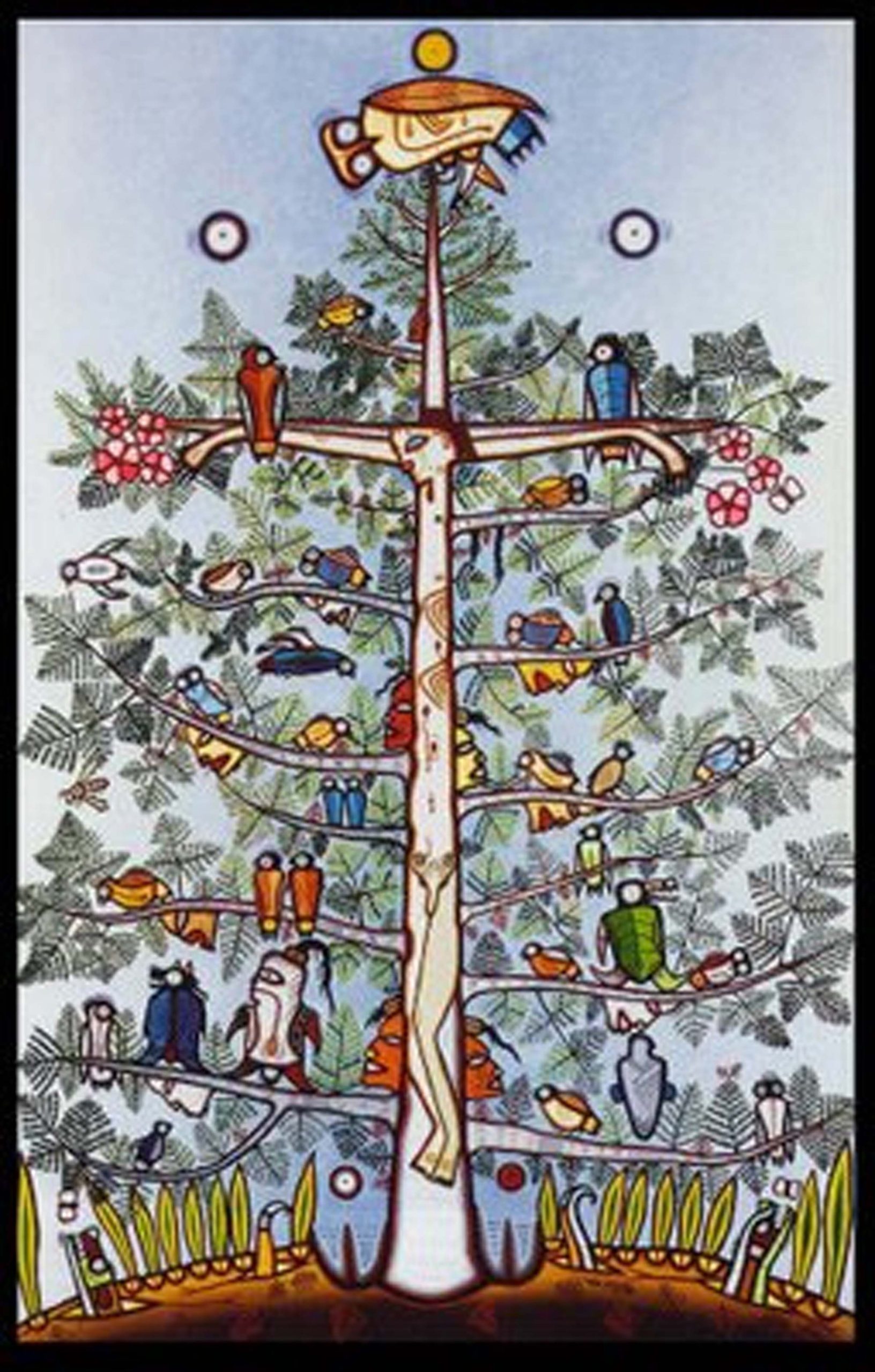

Taylor’s Chicken Truck is a work with a clear political agenda that would have been utterly foreign to the creator of the Psalter Map, made in a culture that believed animals were created in order to be used by humanity. Others artists suggest a greater degree of ambiguity in their presentation of animals and in the implied interaction between “us” and “them.” Few artists could be said to more forcefully display the presence of animals in the landscape than French Enlightenment artist Jean-Baptiste Oudry. His popular paintings depict animals at full scale – that is, the images are life size – but unlike Taylor’s chickens, Oudry specialized in larger animals like elephants and rhinoceroses. Among the more prominent of these is an image of Clara, an Indian rhino paraded throughout Europe in a traveling menagerie starting in 1741. This painting is nearly fifteen feet wide, and standing before it is a startling experience, so tangible is the massive animal that takes up most of the image.

Oudry used contrast and lighting effects to draw the viewer’s attention. For example, he pulls our eyes to the horn – the rhino’s trademark feature – by having it shine with the appearance of reflected light. The physical impact of the image is given an extra jolt, though, when we catch Clara’s eye. In the manner of many human figures in art – though few animal figures – she stares out at us. Our attention is drawn to her eye through the paler gray encircling it, and the splash of white to indicate the sclera – the “white of the eye.”

This is a very carefully observed painting. Unlike other artists, Oudry clearly spent considerable time examining his animal subjects. Still, the pose, mood, and – such as we might imagine it – the expression of the animal was determined by the artist. Rhinos, unlike many animals, do have whites at times visible around their irises, but this feature seems to be deliberately emphasized, here, with the result that the eye appears more human than the eye of a real rhinoceros. This makes it easier for us to identify with the large-scale figure dominating the canvas.

Clara herself must have been quite intriguing, as she became so famous that she inspired a bit of what has been called “Rhino-Mania” in eighteenth-century Europe. She was the subject of numerous paintings, and featured prominently in a human anatomy textbook published by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus in 1747 (and, indeed, her image was used as a sales poster for it).

Clara also appeared in as all sorts of promotional material from cheap souvenirs to elaborate bronzes, lamps, beadwork, and clocks. A remarkable musical clock survives – and still works! – to bear witness to “Rhino-Mania.”

Clara brought the wilds of Asia, as they were imagined, to the cities of Europe. But ultimately, it is unclear from Oudry’s massive image what we are to make of her. Do we pity her captivity (highlighted by the white patches worn into her tough hide, the result of rubbing against her cage for years)? Do we callously gawk, and buy a cheap souvenir? Or do we simply gaze in wonder – a term often used in the period of the Psalter Map to describe the emotion evoked by encounters with large creatures – overcome by the sublime experience of being in the presence of this massive, mighty, strange being?

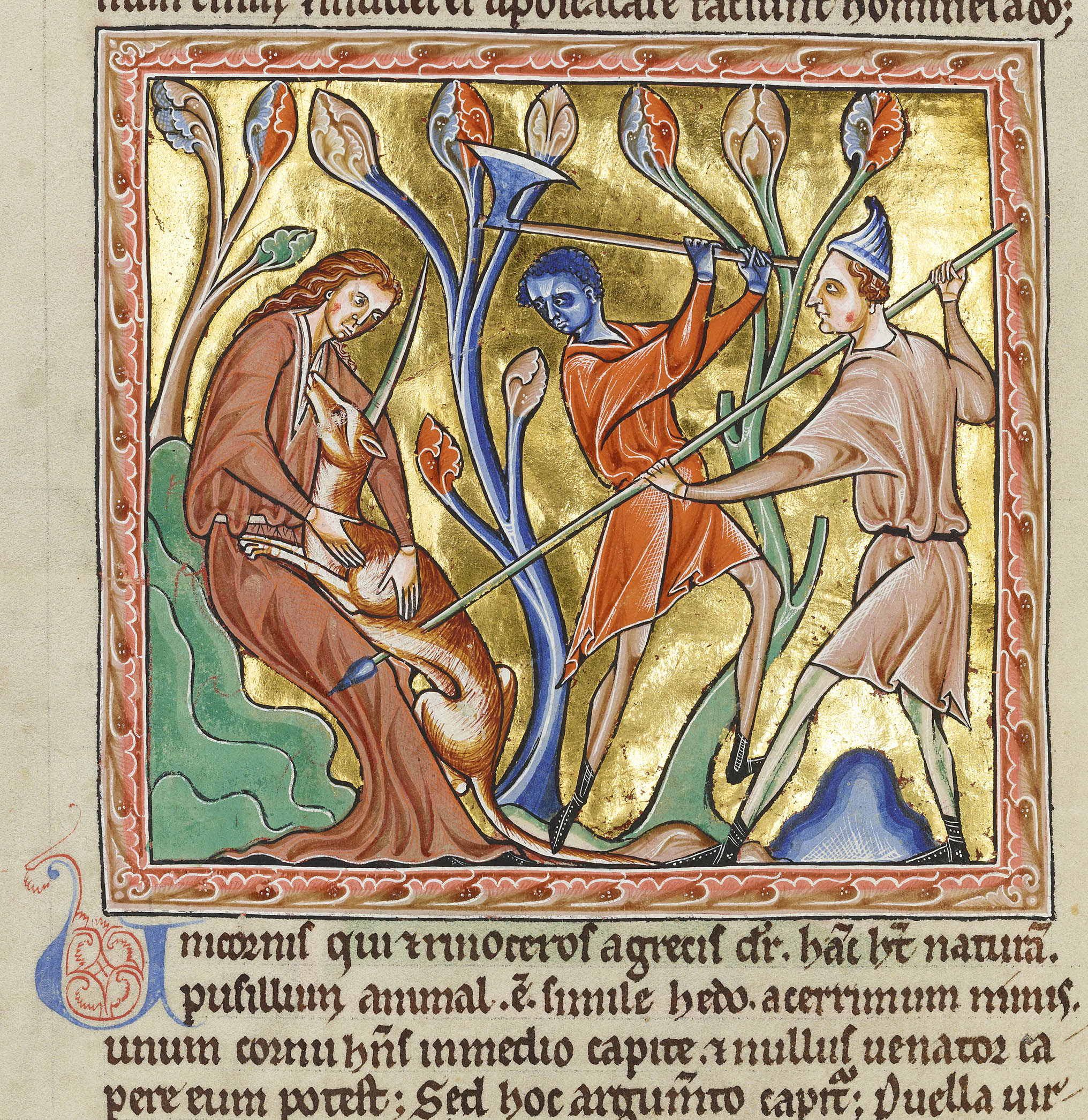

Medieval European images of animals contemporary with the Psalter Map were sometimes much more clear in their meaning. Bestiaries were books of beasts that usually augment the natural history of animals with symbolic and spiritual meaning. These were often made as luxurious illustrated manuscripts – handmade books. A thirteenth-century example in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University has an image of a “rinocerous” – also called a unicorn, both of which mean “one-horn” – being captured and killed.

The first word of the text underneath the image reads, “Unicornis,” Latin for “unicorn.” According to medieval legend, the unicorn could only be captured by a virgin, who would lure it to her lap in order for hunters to kill it. In this case, unlike for Oudry, the animal is not merely a physical fact (as Oudry emphasizes with the massive scale of his paintings), but rather, a symbol. The text of the Bestiary reads, “Jesus Christ is spiritually the unicorn,” and the single horn on its head “signifies that which [Jesus] said, I and the Father are one.”[5] According to medieval Christian belief, then, the single horn of the unicorn was not an accident or the result of natural evolution, but a sign from God to show a religious truth.

In the image, the unicorn seems to be reaching out to the virgin maiden, who instead looks to the hunters who stab the beast with spears. The straight lines of the spears, and the V shape they form, direct our eyes to the wounded creature. Blood wells out from its side, while it looks up to the maiden as if to ask for help. While the text gives us the “meaning” of the unicorn, the image still does not give as clear a message. With whom might we sympathize? With the rough, ill-shaven hunters? With the deceitful maiden, whose gesture nonetheless seems tender and protective? Or with the unicorn? Why give directions for catching and killing a creature, and then present an image that seems to guide our sympathies toward it?

There is a further wrinkle in some medieval Christian images of unicorns. In another bestiary in the Bodleian Library, we see a similar scene. Again the virgin sits at the left edge of the image, cradling the seemingly gentle unicorn in her lap. Again, the hunters attack from the right, stabbing the unicorn from behind. The hunters, though, are represented differently. Now, one of the hunters is painted blue and has tightly curling hair; the other wears a curious, curving cap. The blue figure might remind you of the blue-grey wind faces on the Psalter map. This figure is, like those winds, intended as a representation of a Muslim figure. The hunter in the curved cap is presented in the same tones as the virgin, but the hat tells us what the illuminator wanted us to think about him: European Christians associated this sort of hat, called a Phrygian cap, with Jews. Therefore, when we put together the text’s claim that the unicorn stands in for Christ, this image attempts to present Muslims and Jews as the persecutors and murders of Christ. Such Islamophobic and antisemitic imagery is extremely common in medieval Christian art. Here, then, the artist uses a book about the creatures of the natural world not only to make claims about Christ, but also to reinforce its audience’s prejudices.

The Human Landscape

It is not only animals, but also the landscape itself can be inscribed, even overwritten with human concerns. The iconic Westerns of director John Ford construct the American West as a landscape upon which men can enact their heroism. Ford directed a remarkable 146 films, television shows, and shorts, many of which were Westerns, and of these many were filmed in Monument Valley, an easily recognizable stretch of desert, dotted with massive buttes — straight-sided rock formations with flat tops (which is, of course, what Chico State’s own Butte County is named for, even though what we have are really mesas).

https://archive.org/embed/stagecoach-1939-john-ford

The opening sequence of Stagecoach (1939), one of many films he directed starring John Wayne, gives a sense of what will follow. The very first moments of the film show us the vast, open landscape of the West, into which a stagecoach rides, moving away from the viewer and into the landscape. To a score of triumphant brasses, we see figures that appear to be US soldiers silhouetted against the buttes and then, accompanied by a shift to menacing tones, Native Americans traveling toward us. Indeed, the music played here will be familiar to anyone who has watched old westerns, or even old cartoons, like this shockingly racist clip from an episode of Loony Tunes, featuring the popular Bugs Bunny:

The two bits of music are similar because this was Hollywood’s shorthand way of signaling the presence of Native Americans, almost always presented in negative, dehumanizing ways. When the white soldiers ride by, the score is romantic, filled with soft, uplifting strings. When a group of Native Americans enter the film, the score switches to emphasize heavy, deep drumbeats and lower, deeper tones. This music returns wherever Native Americans are shown on screen, and even some of the times when they are merely mentioned. This conditions the viewer to see them as a menacing force.

Within the first minute of the film, owing in part to the musical score, we know all we need to about the conflict that will be played out across the dusty, dry, barren landscape. Its emptiness, emphasized in shot after shot, is a vital part of the narrative, suggesting that settlers are moving into an unoccupied wasteland, rather than a traditional Native American homeland. This allows the “aggression” of the Apaches (led by the legendary Geronimo) to seem baseless. The director’s choices in how to depict the natural world in the opening sequence, therefore, are central to the morality play that follows.

Like so many other westerns, Stagecoach is in essence an argument justifying the colonization of the continent, and the presentation of its landscape is key to this argument. When we are in a white settler town, we see tidy buildings filled with people dressed in fancy clothes. The Apaches, in contrast, appear in barren stretches. Indeed, one character compares the Apaches to the dangerous animals of the desert, saying that they “strike like rattlesnakes” (1:05). While in some genres, we are encouraged to see nature as a beautiful, restful place, westerns generally paint it as a dangerous, inhospitable place, filled with deadly animals and hostile people.

The Passage of Time

Of course, the natural world is not an inert entity we merely ride over, nor is it constant, as it might perhaps seem in the Psalter Map, not statically frozen in time. Contemporary Scottish artist Andy Goldsworthy often uses his art to highlight the passage of time, perhaps most dramatically – and humorously – in his Midsummer Snowballs (see images here, here, and here). On June 21, 2000, Midsummer Day, he had thirteen giant snowballs, each bearing curious, concealed objects, placed on London streets. The snowballs were so huge – weighing about a ton each – that they took six days to melt. As they did so, they slowly revealed and released their contents.

While the snowballs melted, though, they also drew viewers’ attention to the natural environment, highlighting the cold of the snow, and the warmth of summer. They also invited viewers to think about the natural world as they walked through one of the world’s largest cities. The snowballs were created the previous winter near Goldsworthy’s home in Scotland, and they were packed with natural objects from this rural setting – berries, barley, wool, feathers, and so on. The public was able to interact with them, touch them, break off pieces, and make their own little snowballs. Some attracted birds as they released their contents. Made in the last year of the twentieth century and displayed and destroyed in the first year of the twenty-first, the snowballs place the passage of time before us.

Time is, of course, an important element of the natural world. Time can be a basic element of works of art, a central subject matter, or it can enter it in a more figurative sense, as with these midsummer snowballs that are affected by time and sooner or later are gone, the works themselves vanishing, eaten up by heat and time.

Shiva Nataraja (Lord of the Dance, eleventh century CE) is not perhaps as obviously focused on the natural world as other images in this chapter, but it bears important implications for notions of time and their impact on our understanding of the world, and the universe. This image would have originally been draped with silks, covered with jewels and wrapped in flower garlands, creating an impression very different from that which we see today. Shiva is often described as if one of three main deities of Hinduism (Braham the Creator, Vishu the Preserver, and Shiva the Destroyer). However, Hindus – who generally define their religion by their devotion to an individual god, such as Shiavites or Vaishavites – actually see these roles, and these beings, as more fluidly connected, with beliefs overlapping, contrasting and conflicting.

In this image, Shiva dances with grace in the ānanda tāṇḍava (“dance of bliss”), poised atop a demonic dwarf, whom he easily subdues. The figure is composed of soft, sensuous forms, with a somewhat androgynous body. While a male god, Shiva is here depicted in a rather different style than the muscular gods of ancient Greece and elsewhere. In his rightmost hand, he holds a small drum, which beats out the cycles of creation, whereas the fire in his leftmost hand implies destruction, also suggested by the fire encircling him. Still, he raises another of his hands to us to offer us a sense of calm, which is also reflected in his blithe expression. His raised left foot suggests our eventual liberation from cycles of reincarnation through escape from ignorance, embodied in the dwarf crushed beneath the god’s right foot. In this way, the Shiva Nataraja links back to the Buddhist image by Sesshū that began this chapter. Both present the natural world, for good or bad, bounteous or harsh, as something, ultimately, to be escaped.

There is, though, again a point of trouble to be dealt with: in symbolizing ignorance, the “dwarf” figure relies on an assumption that the outward shape of a human being indicates their inner qualities. This is a foundational assumption underpinning most forms of racism, but it is also a central pillar of ableist thought. That is, able-bodied people often view physical differences (whether or not they impair or disable a person) as markers of intellectual or moral failings, and artists and authors frequently use an external, visible impairment as a marker of internal corruption or evil. Think, for example, of Captain Hook, the Phantom of the Opera, Voldemort, or Darth Vader (and see here for a brief discussion of these issues). While the “dwarf” here is not based on a particular individual, the figure still functions, in tandem with highly idealized image of Shiva, to describe a natural world where interior properties are legible on a being’s exterior.

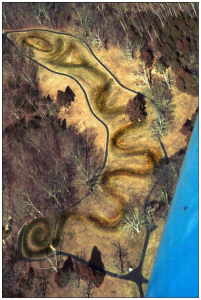

The World in a Snake

In this chapter, we have seen images of the world, the landscape, and the animals and people that inhabit it. One image, though, might be seen as containing all of these concerns. The Great Serpent Mound in Adams County, Ohio (ca. 1070) is a product of the Mississippian Culture, a Native American civilization that flourished from ca. 900-1500. They followed a tradition of mound building that began as early as 1700 BCE and continued for 3000 years. These mounds were usually used to bury leaders or even entire groups with grave goods. The Great Serpent Mound is among the most impressive, 20 feet wide and running 1254 feet from end to end, following its twists and turns. The site was carefully chosen, on a ridge overlooking a stream, thereby granting the mound greater visibility.

The form shows a serpent eating an egg. It is possible that the mound was inspired by a celestial event: it was constructed shortly after the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1066 CE. Cultures throughout the world recorded its appearance in art and text. The comet was closer to the earth than it has been since, and shined so brightly for a week that it could have been seen even during the day. In the Great Serpent Mound, the large oval at the front and the long tail are loosely analogous to the form of a comet.

Seen from the air, the organic form of the mound undulates gently, ultimately terminating in a spiraling tail that roughly balances the mouth, held wide to hold the egg. From the ground, the mound appears as more of a wall or maze, slithering off into the distance. Based on the gigantic scale of the mound, the animal in the landscape is also, in essence, the landscape itself. Turner and Ryder animated the landscape as a malevolent force. Here, though, the serpent seems to be an embodiment of the people who created it. Such mounds frequently contain both human remains and specialty items characteristic of their culture.

The mound is echoed in several works by Andy Goldsworthy, who has constructed a number of undulating walls, perhaps most famously that at the Storm King Art Center in Upstate New York (see here for an image). The wall, 5 feet high and running a remarkable 2,278 feet, took a team of wall builders two years to construct out of stones from the landscape of the Center. These stones are not carved into rectangular blocks, but left in their rough state, emphasizing the natural material rather than the stonemasons’ work. The work is reminiscent of the Great Serpent Mound in its snaking form, of ancient architecture, and of modern and contemporary works of art. It spans a vast amount of space – winding between trees and, for a stretch, disappearing beneath a river – and in so doing, invites us to consider the flow of time. Unlike the large wall on the Psalter Map, Goldsworthy’s wall appears to be part of the natural world out of which it was constructed.

CONCLUSION

Images of nature vary tremendously, from the most terrifying (like Turner’s storm at sea) to the most domestic (like the Snowy Garden). They show catastrophe (Jonah) and struggle (Winter Landscape), but also lighthearted enjoyment (Le Pélerinage a l’Île de Cithère). They show animals as cosmic (The Great Serpent Mound), divine (Temple of the Feathered Serpent), connected to a spiritual web (Tree of Life), and as awesome sites of wonder (Rhinoceros). Nature is among the earliest themes to appear in art, and has remained a vital source of inspiration in the millennia following.

SPOTLIGHT IMAGE III

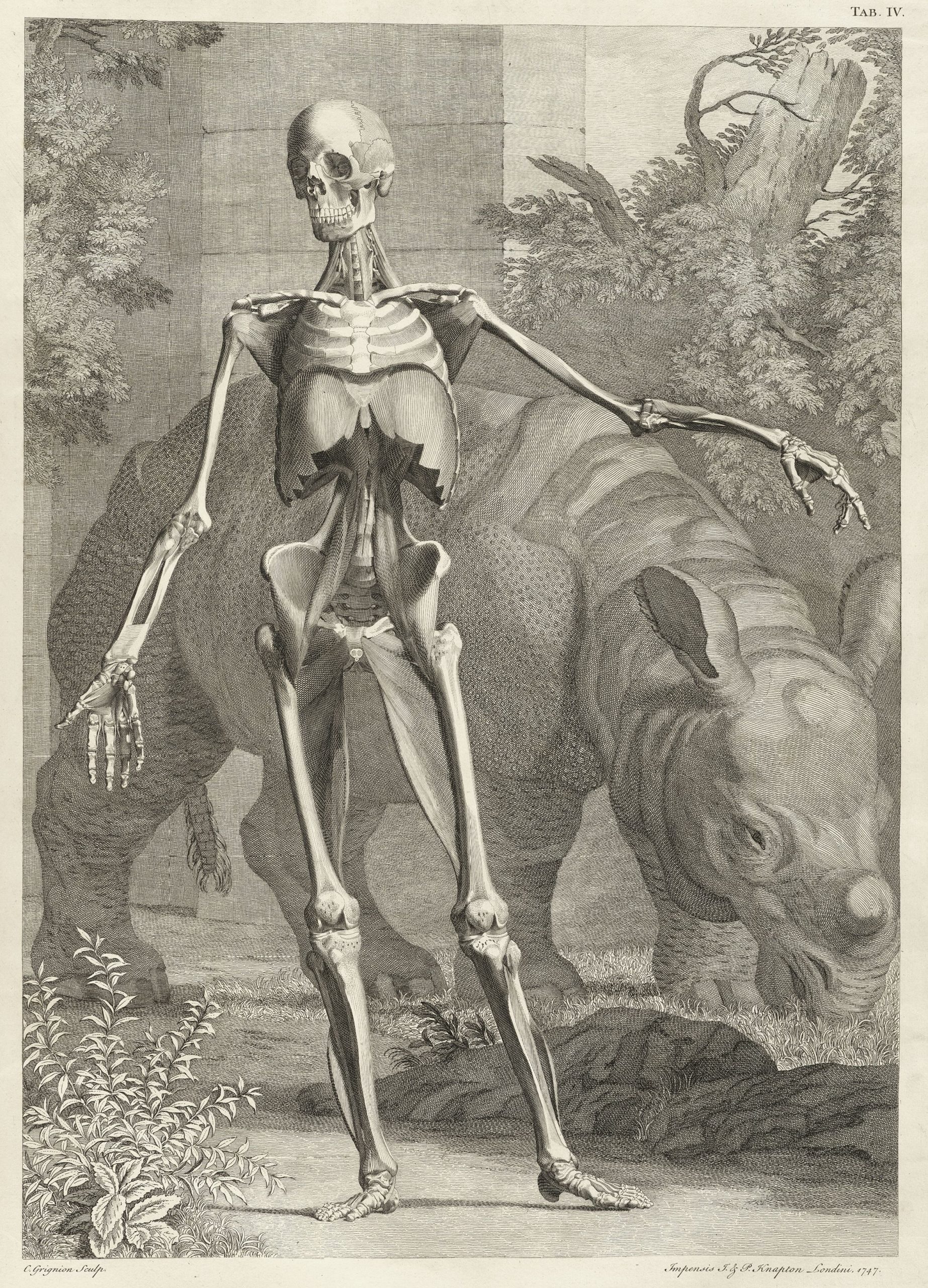

Albrecht Altdorfer, Danube Landscape, Germany, 1520-1532 CE

VIEWING QUESTIONS

- What are the main compositional principles used to design the painting?

- What is the focal point of the image, and what guides our eyes to it?

- How is contrast used?

- How does the image invite us into the landscape?

- Is the work naturalistic?

- Is the work idealized?

- This is often considered the earliest pure landscape painting in Western Art. How does the painting relate to other landscape images you have seen? Is it effective?

Media Attributions

- Sesshū Tōyō, Autumn and Winter Landscape, ink on paper, fifteenth-sixteenth century (Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo). Photo: Public Domain.

- Sesshū Tōyō, Autumn and Winter Landscape (Detail of tree), ink on paper, fifteenth-sixteenth century (Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo). Photo: Public Domain.

- Sesshū Tōyō, Autumn and Winter Landscape (Detail of person), ink on paper, fifteenth-sixteenth century (Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo). Photo: Public Domain.

- Sesshū Tōyō, Autumn and Winter Landscape (Zigzag Diagram), ink on paper, fifteenth-sixteenth century (Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo). Photo: Public Domain.

- Ni Zan, Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, ink on paper, 1372 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Photo: Public Domain.

- Çatalhöyük Volcano. Photo by Remixing Çatalhöyük, CC BY-NC 2.0.

- Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slaves Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming on (Slave Ship), oil on canvas, 1840 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Photo by Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Detail, Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On (Slave Ship), oil on canvas, 1840

- Detail, Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On (Slave Ship), oil on canvas, 1840

- Albert Pinkham Ryder, Jonah, oil on canvas, ca. 1885-1895 (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.). Photo: Public Domain.

- Detail, Albert Pinkham Ryder, Jonah, oil on canvas, ca. 1885-1895

- JonahDetailDetail, Albert Pinkham Ryder, Jonah, oil on canvas, ca. 1885-1895

- Albert Pinkham Ryder, With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow, oil on canvas mounted on fiberboard, ca. 1880-1885 (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.). Photo: Public Domain.

- Rafael Tufiño, Portfolio Las Plenas: Temporal, woodcut on paper (1953-1955). Photo: Éxodo Galeria, Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, by permission of Sucesión Rafael Tufiño.

- Detail, Rafael Tufiño, Portfolio Las Plenas: Temporal, woodcut on paper (1953-1955).

- Temple of the Feathered Serpent, ca. second-third century (Teotihuacan, Mexico). Photo by jschmeling, CC BY 2.0.

- Jean Antoine Watteau, Pélerinage à l’Île de Cythère, oil on canvas, 1717 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). Photo by Jean Louis Mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Detail, Jean Antoine Watteau, Pélerinage à l’Île de Cythère, oil on canvas, 1717.

- Visual flow, Jean Antoine Watteau, Pélerinage à l’Île de Cythère, oil on canvas, 1717.

- Utagawa Kunisada and Utagawa Hiroshige, The Snowy Garden, ink and color on paper, 1854 (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland). Photo: Public Domain.

- Psalter Map (Detail of orb), ca. 1275 (British Library, London). Photo: Public Domain.

- The Creator with Compass, illumination on parchment, ca. 1220-1230 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna). Photo: Public Domain.

- East Wind and Eden, Psalter Map, ca. 1275 (British Library, London). Photo: Public Domain.

- Psalter Map (Detail of orb), ca. 1275 (British Library, London). Photo: Public Domain.

- Psalter Map (T-O Lines Diagrammed), ca. 1275 (British Library, London). Photo: Public Domain.

- Isidore, T-O Map, ca. 600-625, Photo: Public Domain.

- Psalter Map (Eden and England highlighted), ca. 1275 (British Library, London). Photo: Public Domain.

- Dragons, Psalter Map, ca. 1275 (British Library, London). Photo: Public Domain.

- Winds, Psalter Map, ca. 1275 (British Library, London). Photo: Public Domain.

- Blake Debassige, Tree of Life, 1982. Photo: Anishinabe Spiritual Centre.

- Sunaura Taylor, Chicken Truck (2007). Photo: By permission of the artist.

- Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Rhinoceros, oil on canvas, 1749 (Staatliches Museum, Schwerin). Photo by Jean Louis Mazieres, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

- Detail, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Rhinoceros, oil on canvas, 1749.

- Jan Wandelaar, Engraving of Clara and Human Skeleton in Bernhard Siegried Albinus, Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani, 1749. Image: uploaded by Jan Arkesteijn, Public Domain.

- James Cox (ca. 1723–1800), Musical Rhinoceros Clock, ca. 1765–72. Gilt bronze, silver, enamel, pearls, and colored glass, pedestal: white marble and agate. Photo: Bridget Coila, CC BY-SA 2.0.

- Unicorn, Bestiary, parchment, ca. mid-thirteenth century (Bodleian Library, Oxford). Photo by Bodleian Libraries, CC BY-NC 4.0.

- Unicorn, “Ashmole Bestiary,” parchment, England, 1201–1225 (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 1511, f. 14v). Image: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, CC BY-NC 4.0

- Shiva as Lord of Dance (Nataraja), copper alloy, ca. eleventh century (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Photo: Public Domain.

- Serpent Mound (Aerial), ca. 1070 (Adams County, Ohio). Photo by Timothy A. Price and Nichole I., CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Serpent Mound (Ground), ca. 1070 (Adams County, Ohio). Photo by Eric Ewing, CC BY-SA 3.0.

- Altdorfer-Donau

- "Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, Ni Zan," The Metropolitan Museum of Art ↵

- "Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, Ni Zan," The Metropolitan Museum of Art ↵

- James Burr, “The Lure of the Sea,” Apollo 133 (April 1991), 279. ↵

- The Bible, New International Version, Jonah 1:4-1:17. ↵

- Willene B. Clark, A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary, Commentary, Art, Text and Translation (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006), 126. ↵

The amount of variation between the highest and lowest values in a work of art

A path either represented or implied

An even use of elements throughout a work

A Buddhist sect focused on zen (literally, meditation) as the path to enlightenment, in contrast with Buddhist sects that emphasize more formal rituals. Closely tied to the practice of sumi-e painting

Japanese painting done in black ink

The property of an image where its two sides do not mirror each other, but still have approximately the same visual weight, the same amount of detail or shapes or color, and so on

Techniques used to draw attention to one or more points in a work

Known as Daruma in Japanese, the founder of Zen Buddhism. Accounts of his life are largely legendary, with few details known to be accurate. A popular subject for art and literature

In Buddhism, the state achieved by the Buddha, and the goal of Buddhists, characterized by deep understanding of the self and of the world around it

In Buddhism, the end of cycles of reincarnation and a release from all desires and the resulting suffering

A short memorial in memory of a person who has died, often written on a tombstone

Japanese term for the appreciation of a simple, even austere lifestyle, often reflected in art

A person who lives a very simple, austere life, usually to achieve spiritual goals

An image where the main subject is the natural world, itself, rather than people or other figures doing something in the world

A type of scale based on relative importance, in which more important figures are represented as larger than less important figures around them

Making an image look like the “real world”

Literally "picture-writing," the recognizable forms in images, often with symbolic meanings. Also used to describe the study of such images and their meanings

An eighteenth-century art form, especially in France, Germany, and Austria, characterized by light, breezy, cheerful, and sentimental imagery, often of wealthy people (or the rural poor depicted as if wealthy) playing in nature

winged cherubs or cupids

a form of printmaking where a wooden block is carved in reverse, inked, and then pressed into paper to create an image

European period running from approximately 400 or 500 CE through 1400 or 1500 CE, depending on location

Symmetry wherein two sides of an image mirror one another

The property of an image that is symmetrical around a central point or axis, like a sunflower viewed head-on

line running down the center of a figure

Similar to pattern, repeating an object or element throughout a work or a part of a work, but generally less precise or formal than a pattern

The direction a map faces at its top. The term comes from medieval Christian mapmaking practices, which usually put the east ("orient" in Greek) at the top

A volume containing the biblical Book of the Psalms

Paying for the creation of works of art; a person who provides patronage is called a patron

An explanation of the origins of the world and universe

An ancient Roman method of execution by being hung or nailed to a large wooden cross and left exposed to the elements to die of thirst and hunger, or via suffocation caused by weakness that prevents the drawing of breath; most famously, the method of execution used on Jesus, the founder of Christianity, though many accounts say that while hung on a cross, he was stabbed in the side before dying of crucifixion, itself

Medieval books of beasts that usually augment the natural history of animals with symbolic and spiritual meanings

A handmade, hand-written book