11 Death

How do artists grapple with the idea and reality of death?

Death, the most implacable force in the universe, awaits us all, at least until science finds a route to immortality (embodied or disembodied). Many religions offer hope for some sort of continued existence after death, usually in the form of either an afterlife or reincarnation — being reborn again into a different body. This chapter considers works of art from throughout the world, and from ancient Egypt (famous for its interest in an afterlife) through the modern period. It is divided into sections dealing with grief, disease, funeral rites and rituals, journeys to the afterlife, and embodiments of Death itself, and then turns to the practice of human sacrifice, beliefs in the undead, and finally art that examines the fascination with death in pop culture. Much of this material is difficult, but important. Death is a theme in the work of just about every culture, and we must ultimately figure out how to face it. The works discussed here offer several different approaches to this grim subject.

A note about this chapter

This chapter was written by the students in my Chico State ARTH 400W: Public Art History course in Fall of 2024. In the syllabus, I describe the course as follows:

The UC Davis Office of Public Scholarship and Engagement defines “public scholarship” as “research, teaching, and learning that has an impact for publics beyond the university.” As the name indicates, this work involves scholarship — the generation of new knowledge, ideas, methods, and creative works — that is presented in a manner intended to be accessible to the general public. Examples include popular nonfiction books, articles and op ed pieces, public lectures and courses, signage in museums, historical monuments, national and state parks, and so on, and informative podcasts, videos, and websites. The goal of this work is to address social and cultural issues, contribute to contemporary debates, and improve the public’s understanding of matters of concern. Students in this Special Topics course will learn to identify, analyze, and produce public scholarship, taking the work we do within the university out into the wider world.

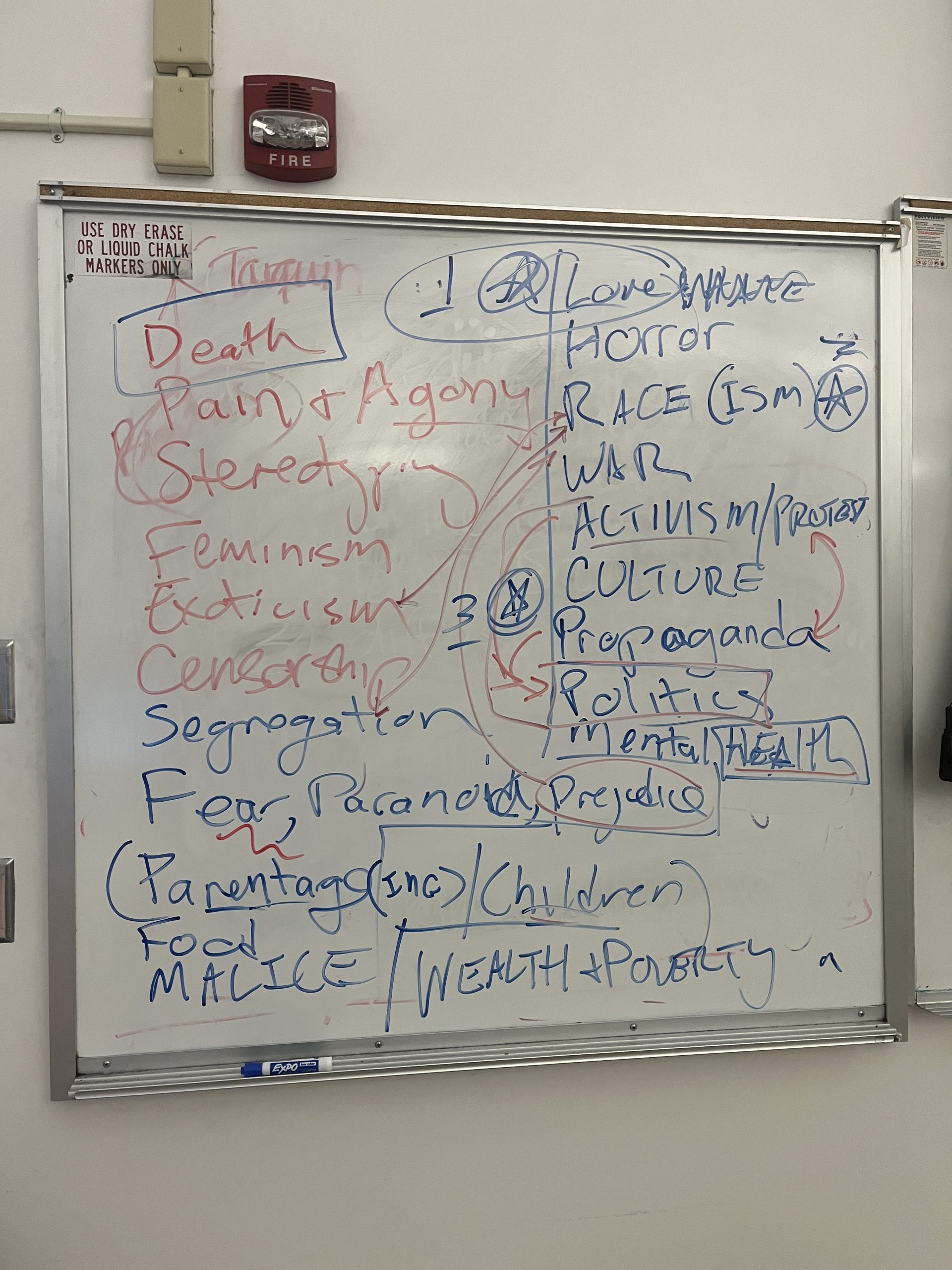

One of the main assignments for the course was for the students to collaborate on a chapter for this online OER (Open Educational Resource — that is: free) textbook. The course had 27 students who, after class discussions, chose the theme for the chapter. Harrowing subjects dominated the conversation (e.g. pain, fear, paranoia, malice, horror, racism, war, poverty) though some students did suggest subjects that were more neutral (e.g. politics) and even some that were potentially more positive (e.g. love, family, children, activism).

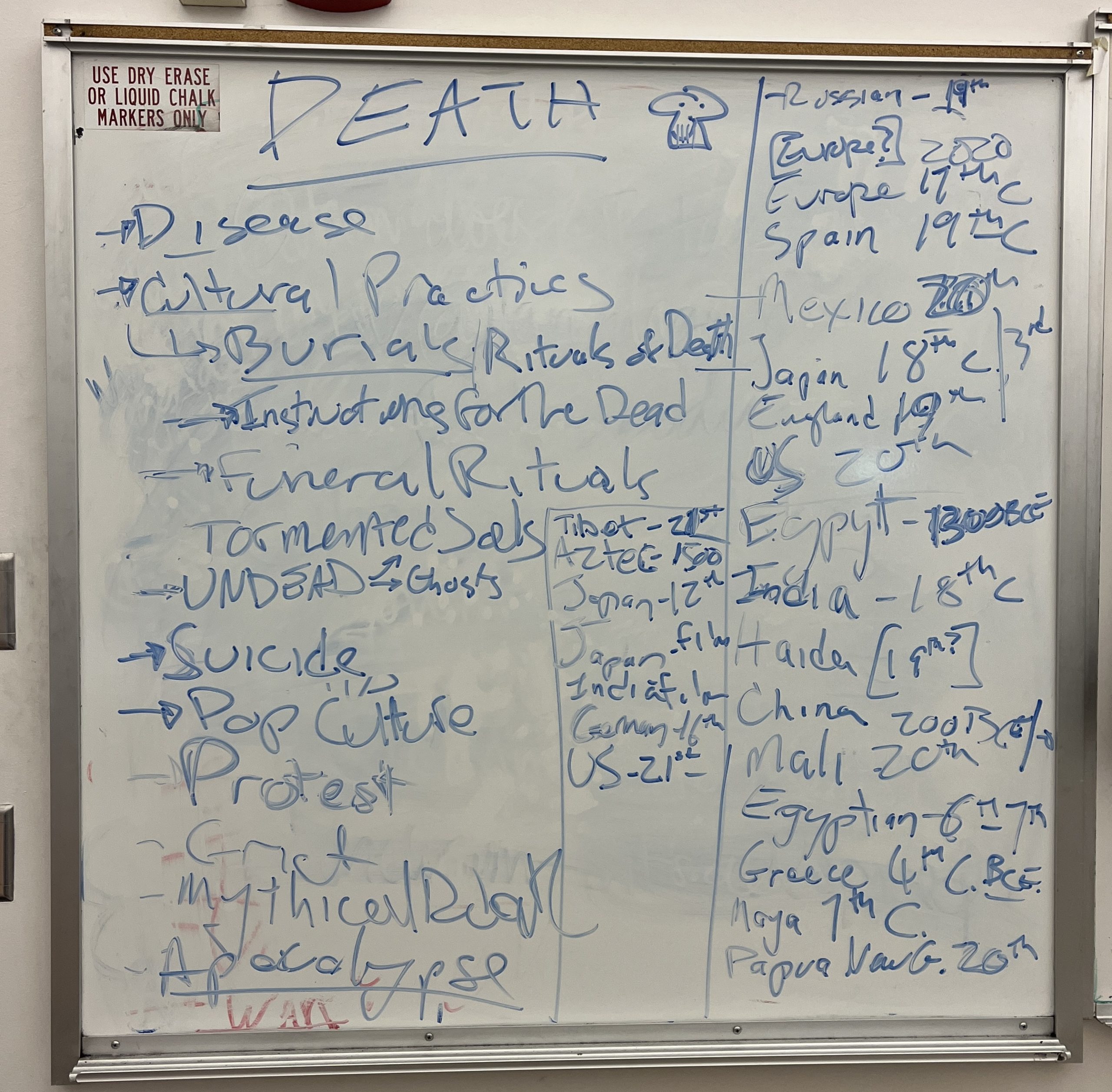

Once Death had won the day — as, really, it always does in the end — the students came up with a series of sub-themes to divide up the potential material, and began suggesting specific works. In doing so, we kept loose track of the cultures, regions, and periods they represented to make sure we were achieving the same sort of global, pan-chronological coverage found in the rest of the chapters.

Students then formed groups around subthemes (some of which developed in unexpected directions as they got to work), produced drafts, worked through a series of edits and suggestions that I provided, and then completed their final drafts. I then edited these again, and strung them together into what I hope to be a reasonably coherent structure. Because of how this chapter was written, it does not have the same structure as the other chapters in the book. There are no “Spotlight Images.” There is, though, a great wealth of fascinating images discussed throughout the chapter! I am quite proud of the work they produced, extending the focus and reach of their studies beyond the college classroom, producing a work of published public scholarship that I am confident is a valuable addition to this textbook, which is in use in art appreciation courses all over the United States and beyond. I hope you enjoy their work!

The student authors are:

Leeah Barrett, Preston Breeze, Lauren Ceriani, Amaris Cisneros-Valdez, Dane Clarke, Eric Culpepper, Idaly Flores, Kai Fritz, Bo Gurnee, Shenise Halsey, Noah Jibikilayi, Cassidy Kuharski, Jackilyn Laffey, Esther Lawson, Jasmine Lezama, Kent Moore, Kelly Munson, Portia Osa, Adelaide Sands, Aimee Sayer, Chad Schneider, Raven Shaw, Marlo Sherman, Tyler Stewart, Michelle Stout, Ximena Villaneda, and Taylor Watkins.

Grief and Memorialization

How can artists convey the bottomless grief that often accompanies the death of a loved one? How can they give voice to their individual suffering, or the suffering of groups to which they belong? This section features a series of images that attempt to express the emotional toll of such loss.

Ilya Yefimovich Repin’s Ivan the Terrible and his Son Ivan (1883-1885) portrays grief through several means. This painting presents the first tzar (emperor) of Russia, Ivan IV Vasilyevich, known as “the Terrible,” who ruled in the late sixteenth century. He is the older figure on the left, holding his adult son, Ivan Ivanovich, in anguish. According to the most widely circulated historical accounts of the event, the father and son quarreled over an ongoing war, with the son arguing that too many had died and it was time for peace, and the father holding fast to his position that the war needed to continue. In some versions, the tzar first struck his son’s wife, and then struck his son in a fit of rage, dealing a lethal blow he immediately regretted to his son’s head. Ivan Ivanovich died a few days later. In this painting, the fatal staff lies in the foreground, and the overturned furniture and rumpled carpet suggest the extremity of the violent events that unfolded here.

The common accounts of the death of Ivan Ivanovich are likely inaccurate, but were nonetheless likely the versions known to Repin.[1] The painting shows Ivan’s intense regret, as he cradles his son’s head with a look of shock and trauma on his face. Ivan Ivanovich looks stunned, physically and emotionally. His face conveys a feeling of betrayal in his final moments. The artist was inspired by the time of political discord in his country, which led to violent events. The most notable of these, the one that inspired this painting, was the assassination of the Russian Emperor Alexander II on March 13, 1881, in a terrorist bombing in Saint Petersburg.

The piece depicts the fragility of life, and draws its emotional power from the permanence of death, even though caused here by a swift and impulsive action. The expression on Ivan the Terrible’s face — eyes wide and bulging, brows raised in anguish, hair wild and askew — shows his intense mourning mixed with his horrified guilt. This painting stands out from many other images of grief for the rawness of its presentation, which led Russian Emperor Alexander III — son of the assassinated Alexander II — to ban it from public view. The work has continued to inspire strong, even violent responses. It has been attacked at least twice, once while Repin was still alive and able to restore it. The power of this work remains so vivid that it was attacked again, in 2018, in an incident that may have been inspired by a Russian nationalist view that holds that Ivan IV Vasilyevich did not kill his son, and was not “terrible,” as his common epithet claims.[2]

Another Russian painter, Maxim Vorobiev, took a more metaphorical approach to expressing grief over the death of his wife. Expressing the emotions he was feeling through this allegorical painting may have helped him cope with his grief. Traditional European symbol guides with which Vorobiev may have been familiar tend to associate oak trees with life. Here, a mighty oak is shattered by a sudden bolt of lightning, suggesting a life being taken away suddenly, without warning. The tree clings to a craggy cliff in a wild storm. Is it high within the clouds or battered by fierce ocean waves? The use of cold, dark muted colors, most nearly gray or black, establish a turbulent, grim tone. Though the work shows neither the dead woman nor those she left behind, it conveys a grief that feels rough and fresh, like an open wound.

At times, the death of an individual can galvanize a community or even a nation. This was the case with the 2020 murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who was tried and convicted of three murder charges.[3] Police were responding to a call from a store claiming that Floyd paid with a counterfeit $20 bill. As captured on video by multiple witnesses, police body cameras, and security cameras, an officer handcuffed Floyd, who informed them that he was recovering from Covid-19 and having trouble breathing. After Floyd fell to the ground, Chauvin knelt with a knee on Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes. Throughout this time, Floyd repeated numerous times that he could not breathe, and at the end of it, he was dead.

First in Minneapolis, and then throughout the United States, mass protests erupted. Many protestors affiliated themselves with the Black Lives Matter movement, which Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi founded in 2013, in response to the killing of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Black boy shot by George Zimmerman (who was later acquitted of a murder charge). As part of this protest movement, artists across the country turned blank walls and streets in city centers into canvases to express grief and outrage about the long history of anti-Black violence, especially the deaths of Black men and boys at the hands of police officers. The first George Floyd mural was created by community artists Cadex Herrera, Greta McLain, and Xena Goldman just hours after Floyd’s murder. The mural was painted on the side of a grocery store in Minneapolis, Minnesota, just down the street from where Floyd was arrested and then killed on the sidewalk by police officers. The mural quickly became a memorial site for locals and visitors, who came to honor Floyd and mourn his needless, senseless death.

Herrera, McLain, and Goldman’s mural features a portrait of Floyd, positioned in front of a large sunflower that functions like a halo behind his head. The black center of the flower is inscribed with the slogan, “Say our names,” followed by a long list of Black people killed by police, including Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old boy shot while playing at a recreation center, and Breonna Taylor, a medical worker shot seven times while unarmed in her own home. As Herrera explains:

That connects to all the people who have been killed by the police: I wanted to make sure they were also represented. George Floyd wasn’t the first death, and now—just recently there’s been a murder; another policeman just shot another Black man—now George Floyd is not the last.[4]

The artists painted Floyd’s name radiating out from either side of the portrait. The letters are painted in the same yellow as the petals of the sunflower, and they are filled with small blue figures raising their fists, which recall the lively, abstracted style of Keith Haring’s social protest art.[5] As Herrera explains, these figures are a “community inside his name, demanding change, raising their fists in support of George Floyd.”[6]

The text at the bottom of the image, which reads, “I can breathe now,” was added after the artists polled the local community to see what they wanted it to say. The text itself was added by a member of the community, and the artists also invited people from the supportive crowd that watched them paint to join them in creating the mural. In this way, the work becomes a stand-in for Floyd’s stolen voice, for the artists of the mural, and for the larger community the artists were striving to represent.

Most images memorializing the dead present them as they looked in life, as does the George Floyd mural. However, in then-radical images, two Renaissance artists presented Jesus as a corpse: late-fifteenth century Italian painter Andrea Mantegna and sixteenth-century German painter and printmaker Hans Holbein the Younger. Both present the body of Jesus, after his death, marked with stigmata — the wounds from the large nails used to hang him from a wooden cross. Both also present the body from unexpected angels. Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1480–1500) positions the viewer at Jesus’s feet, with the corpse highly foreshortened. His feet seem almost to jut out of the canvas into the space of the viewer. We see three mourning figures on the left, likely Mary Magdalene, who anointed the body with oil before its burial, Jesus’s mother Mary, and John the Evangelist. Christ is delicately haloed, which reminds the viewer of the Christian belief in his divinity. Jesus’s calm face, his relaxed brow, suggests that he is now peacefully at rest in death. His wounds are clearly on display, but they seem to have been cleaned and dried. Nothing here suggests the eventual decomposition of the human body. It is possible that Mantegna made this image — which became quite influential — for his own personal comfort and devotion after the death of two of his sons.[7]

In contrast, Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521-22) shows a grotesque life-size depiction of the stretched and unnaturally thin body of Jesus lying in his tomb. The figure, shown from the side, is presented as if just within the picture plane. Jesus’s right hand, turning green and marked with a wound from one of the nails by which he was attached to the cross, seems — like the feet in Mantegna’s image — to press into the viewer’s space. Holbein presents Jesus, the central figure of Christianity, with the appearance of an ordinary human corpse. The painting is the actual height and length of a coffin, which is crucial to its disturbing effect.

Holbein, a Christian, would have believed that Jesus was not merely a man, but also the son of God and (at the same time), God himself. Why, then, emphasizes his very human death? The work was likely commissioned by Bonifacius Amerbach, a legal scholar, as a memorial to his parents and his recently-deceased brother Bruno, to be displayed in their tomb.[8] Having lost those close to himself, perhaps Amerbach took comfort in the idea that the god he worshiped suffered the same fate as members of his own family.

A similar tension between the grand and the ordinary lies behind several paintings by American painter Kehinde Wiley. Throughout his career, since his breakout show at the age of 26, “Passing/Posing” at the Brooklyn Museum, Wiley has been seeking to reimagine what images of young Black Americans might look like, asking, “What if he reversed the terms, simultaneously demystifying the Western canon and endowing Black youth with Old Master grandiosity,” with the sort of dignity imparted to subjects by painters like Holbein?[9] “Down” is a series of large-scale portraits of young Black men inspired by Holbein’s The Dead Christ in the Tomb, and he painted a new version of it (Kehinde Wiley, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, oil on canvas, 2008: see here and here for images) as well as of Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Kehinde Wiley, Dead Christ in the Tomb, oil and enamel on canvas, 2007: see here for image).

Wiley references the iconography of death and sacrifice in European art, tracing it across religious, mythological and historical subjects. His paintings show figures struck down, wounded, or dead, referencing iconic paintings of mythical heroes, martyrs, and saints. All of his figures are Black, in contrast to the content of the European works he emulates. Some of Wiley’s paintings puts death in full view, asking us to pause, witness, and grieve the senseless deaths of Black men and women. His versions of Renaissance paintings are often massive. His Lamentation over the Dead Christ is more than nine feet wide and his The Dead Christ in the Tomb is twelve feet wide, giving them a grandeur even beyond that of the originals. They are also painted in exquisite detail and vivid colors that are quite overwhelming when viewed in person.

These remarkable images cannot be reduced to a straightforward attempt to mourn the victims of anti-Black violence. As David J. Getsy writes:

When these paintings have been discussed, many critics have rushed to see them as laments about the dangers faced by black youth. While this is undoubtedly part of the context in which these works operate, to see these works only as this misses the ways in which they strategically deploy eroticism to activate and invert the power dynamics that often go uninterrogated in the history of Western art.[10]

The titles of both of these images, borrowed directly from their Renaissance inspirations, suggest that the figures are dead, but there are no signs of violence, no wounds, no onset of the rot that is so troubling in Holbein’s unflinching image. Wiley’s figures suggest health, not death. Nothing mars the bright white of the t-shirt of the man in his Lamentation over the Dead Christ; he might merely be asleep. The figure in Wiley’s Dead Christ in the Tomb seems to turn to look directly out at the viewer, to make eye contact. Does his open mouth suggest the slack expression of death? Or does he perhaps call out to us? The wall behind him explodes with life, with stunningly rendered leaves and flowers. Perhaps, then, these images challenge narratives of Black death with vibrant images of life.

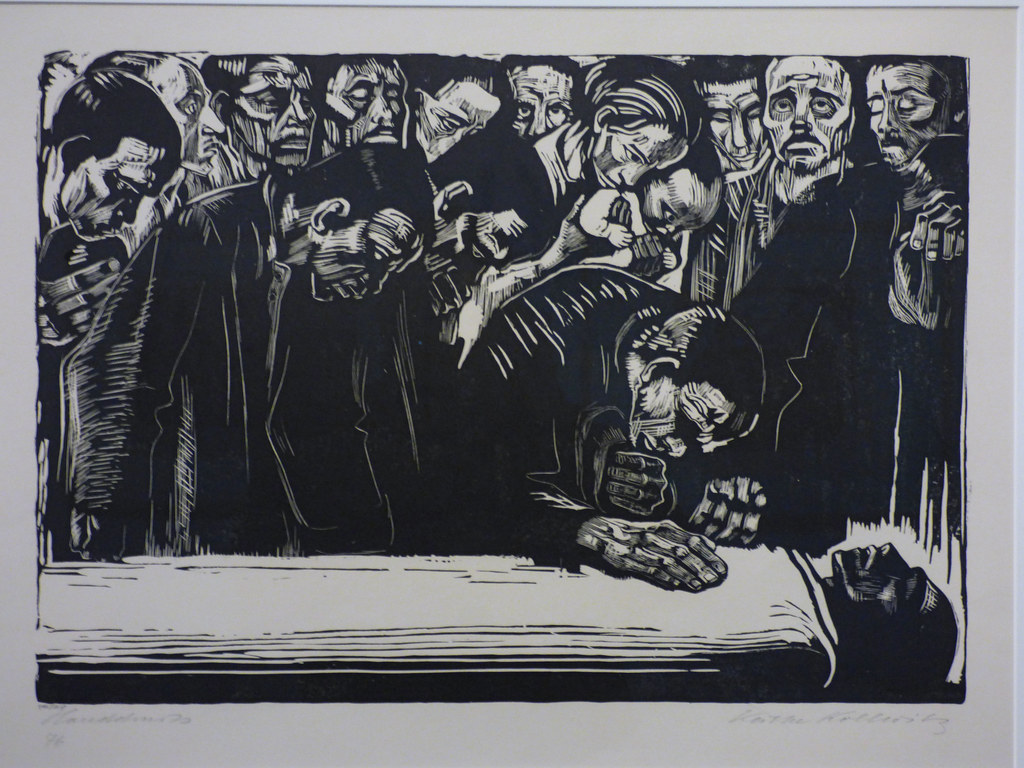

In Kathe Kollwitz’s Memorial Sheet of Karl Liebknecht (Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht) (1919-1920) the grief-stricken mourners that loom directly above the deceased have pale, sunken faces that remind us of their skeletons underneath. The implied line that runs across the composition slopes downwards from left to right, following the increasingly bent figures. Each figure along this line shows a further step in the cycle of human aging, conveyed by their hunched forms and the increasing lines and wrinkles carved into their faces. These declining figures, and the focus of their eyes, guide us to look at the face of the dead. Several figures in the background watch in a mixture of horror and sadness, making a spectacle of the open casket.

Kathe Kollowitz (1867-1945) was a German artist who specialized in printmaking, sculpture, and painting. Her work centers on social issues, motherhood, war, and death. She started out as a painter, but turned to the mediums of sculpture and printmaking after the influence of fellow artist Max Klinger.[11] Kollowitz endured the challenging times of both World Wars, which affected her work, as did the loss of her younger son and later her grandson, both of whom died while serving in these respective wars.[12] Death became one of the key subjects of her work, which are harsh in their formal qualities, but nonetheless convey deep empathy for those mourning.[13] Liebkecht, the subject of the work, was an activist politician, a staunch communist and supporter of the rights of workers who voted against German entry into World War I and then tried to overthrow the government to stop the war. His life came to a sudden violent end when counterrevolutionaries shot him while he was under arrest.

In Memoriam Karl Liebkecht was, remarkably, only the second woodcut that Kollwitz made.[14] The decision to make this piece of art as a woodblock print was a deliberate one, but how can we determine this? What woodblock prints generally offer over paintings or sculptures is the ability to make high contrast, 2-D images in multiple copies. This means that it is possible for many people to own original prints of this image, which seems in concert with Liebknecht’s own politics. Further, woodcut images can be quite stark and evoke strong reactions, which could be what Kollowitz was seeking. Kollwitz uses broad areas of black ink, broken up by thin white lines to create a somber atmosphere. The extreme contouring of the figures’ faces, along with the high contrast achieved with the use of stark white paper and black ink, create a sense of shock accompanying the death of Liebkecht. This image is hard to look away from, making the viewer have to face and accept the reality of what’s in front of them — and what awaits us all.

Death as Abstraction

All of the previous examples here of grief in art are representational. That is, they portray some aspect of reality in a more or less straightforward, recognizable way. Even Vorobiev’s Oak Fractured by Lightning, though it is a symbolic representation of death and grief, is still a clearly recognizable image of a natural scene. Some artists, though, seek to express grief partially or purely in abstraction, in art that does not represent any recognizable images.

Works from Mark Rothko’s “Black and Grays” series, like Untitled (Black on Grey) (acrylic on canvas, 1969-70, MoMA, New York City: see here for image), are purely non-representational, and yet work to express grief. The stark color palette of dark, muted tones conventionally convey despair and isolation, though these associations are cultural rather than natural. In some societies, white is the color of death and mourning, perhaps inspired by the color of bone, whereas in others, it is black, perhaps suggesting the darkness of the grave. It’s likely that Rothko’s “Black and Gray” series, produced in the year leading up to the artist’s suicide, was deeply influenced by its creator’s emotional state. We know this partially because of how open Rothko was about his artistic motivation. In a 1957 interview, Rothko denied any connection to the larger art movement of abstractionism and the concept of himself as a “colorist,” saying:

I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on — and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions… The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point![15]

A few features of the “Black and Gray” series contribute to their sense of grief and despair. First is not the use of color but the near complete lack of color, in contrast to Rothko’s usually colorful work. Typically, Rothko painted an undercoat of color even in his darkest works, but not in the “Black and Gray” series, the name of which emphasizes its grayscale palette, limited to shades rather than hues. Secondly, Rothko incorporated a border of white in each field of color, typical only to his late career, which separates and isolates each color from one another, rather than allowing them to overlap and blend at the edges. Finally, these last of Rothko’s works are, while still fairly sizable, much smaller than his earlier paintings, This lends a more personal feeling to the experience of viewing them. They pull the viewer forward, drawing us into a more intimate interaction with them than his larger, brighter canvases, which tend to push the viewer back several steps. Drawn in close, into their colorless world, the viewer can perhaps feel some fraction of the grief Rothko was living with in the final year of his life.

Artists have also used conceptual art — art in which the idea or concept presented by the artist is considered more important than its appearance or execution — to express profound grief over loss and death. Conceptual art is frequently non representational, or the representational elements are being used to convey complex ideas which defy their traditional meaning. Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987-1990, MoMA, New York City: See here for image) merely presents two ordinary and identical clocks hung directly beside one another. They are to be set to the same time, but eventually, one will slow and stop while the other carries on. This piece is widely understood to memorialize Gonzalez-Torres’ relationship with his partner, Ros Laycock, who died from AIDS in 1991.[16] Gonzalez-Torres succumbed to the same disease five years later.

While this work might at first seem quite simple in comparison with the elaborate paintings discussed throughout the chapter, it is nonetheless a beautiful, even profound symbol of the grief that lies in wait for most couples in long-term loving relationships. Each tick of these standard, mass-produced clocks is like the beating of a heart, and so the stopping of one conveys the profound grief and sense of abandonment often experienced by a surviving partner whose heart keeps ticking on alone.

Dealing with Deadly Diseases

Deadly disease outbreaks have long provided opportunities for artists to create and disseminate information and propaganda in the attempt to sway the opinion of the public. During outbreaks of measles in Japan’s Edo Period (1603 to 1867), woodblock printing became an affordable way to distribute information to quarantined civilians.[17] The print genre known as Hashika-e, or “Measles Prints,” was used by businesses and political groups to spread eye-catching propaganda, often in the form of satirical social commentary.

Utagawa Yoshifuji’s print Defeating the Measles Demon (1862) turns the fight against disease into a literal battle. Along with a high death rate, measles epidemics affected the economy, threatening the livelihood of any business that involved close social contact or the sale of alcohol.[18] In this example of Hashika-e, owners of such threatened businesses are depicted as a team of heroes attacking the Measles Demon. The heroes, some in the short robes of workers and others dressed in fashionable kimonos (formal robes tied at the belt with a wide sash), descend on the massive, rash-covered demon. They appear in a flurry of action poses. The demon, with haggard features and claw-like toes, falls like a giant tree under their coordinated attack. The print’s action is centered on the page, almost centrifugal, with a churning, spinning motion like a whirling dance made of fluttering silk and cotton.

Most of the business owners in this print are depicted with heads that suit their profession. The figure in a lapis blue kimono toward the center of the right side represents a sake vendor, with his head shaped like a red sake cask. The more casually-dressed figure with a wooden bucket for a head may represent a public bathhouse owner. At the upper right is a geisha (a female entertainer trained in singing, dance, musical instruments, and the art of conversation, who also, at times, performed sex work) who attacks the demon with her iconic wooden pillow. Given the expectations that geishas would always present as demure and elegant, is it particularly significant — and perhaps intended as particularly humorous — that she rolls up her fancy sleeves to get in the fight. Each of these attacks are somewhat comical, but the business owners’ collective fury is enough to bring down the giant demon.

Hashika-e often depicted the public’s distrust of those who profited from epidemics, so the two figures in this image who are defending the demon are likely to be a doctor and a pharmacist. The pharmacist, at the lower left, seems to throw a figure, wearing a white medicine bag in place of its head, over the demon to shelter it. With the rising distrust of doctors and their expensive remedies, the woodblock printmaking industry thrived by selling Hashika-e that included written instructions for home remedies, magical healing rites, and advertisements for counterfeit medicines.

Like “Measles Prints” in Japan, magazines and newspapers were an affordable way to disseminate information and propaganda in Europe and the US during disease outbreaks. The art was similarly graphic, and was reproduced with woodblock printing, lithography, and metal etching. During the London Cholera outbreak of 1866, illustrator George Pinwell drew a cartoon that directed blame for the ongoing deaths at the local government.

Part of the cartoon’s title reads “Open to the poor, gratis [free], by permission of the parish.” “Parish” here refers not to a church but to local government, which Pinwell implies should have been caring for the poor. Pinwell’s cartoon, which was published in Fun Magazine, was likely a response to the findings of epidemiologist John Snow, who discovered the link between the cholera epidemic and city drinking water being tainted with improperly managed sewage.[19]

In Death’s Dispensary, the skeletal specter of Death pumps water for the poor of London. The crown Death wears is likely a reference to “King Cholera,” one of the names given to the disease in Europe.[20] The woman and children who come to gather water have gaunt faces that almost look like skulls; their cheekbones and chin bones are prominent and there are dark shadows around the woman’s eye sockets. Their poverty is evidenced by the children’s bare feet, and by how the woman’s toes poke out of her worn shoes. These struggling figures, downtrodden by poverty, have come for life-giving water but, with Death operating the pump, they will instead contract a deadly disease. Such advocacy eventually resulted in improvements in London’s sewer and drinking water infrastructure, which led to a dramatic reduction in deaths, and eventually the eradication of cholera in the city.

While printed art could be used to criticize those in power during disease outbreaks, it was also used to target specific ethnic groups as the bearers of disease, such as the next work, which was published in Puck Magazine in the US. In response to an outbreak of cholera in Great Britain that was believed to have come from British-controlled Egypt, Austrian immigrant Friedrich Graetz created a cartoon captioned, “The kind of ‘assisted emigrant’ we can not afford to admit.”[21] In the image, a skeletal figure sitting on the prow of a ship bearing the British flag holds a scythe over its shoulder. The figure wears a western fantasy of Turkish clothing, including a red fez hat and a short red vest. Wrapped around its legs is a tattered sheet that resembles traditional baggy Turkish trousers. The edge of the sheet is labeled “Cholera.” The perspective of the image makes the figure seem huge in comparison to all of the tiny humans on the shore.

As the British ship approaches the shores of New York, a rowboat confronts it, filled with men from the Board of Health who are ready to douse the ship in carbolic acid, a poisonous chemical that was then used as a disinfectant. Lining the shore are angry Americans, shouting and waving clubs. Aimed at the ship are canon-like bottles along a wall labeled “Defensive Battery,” filled with more disinfectant. Within the defensive wall is a round building labeled “Castle Garden,” which was a major immigration center in New York.[22]

Fear of death by disease during major epidemics can manifest as fear of foreigners, and lithographs like “Assisted Emigrant…” could magnify or direct that fear in any era. In recent years, we have seen fear of pandemic diseases similarly weaponized against a range of ethnicities and nationalities. Such images argue that the people themselves are, in essence, a disease, and such dehumanization often leads not only to racist laws but also to direct violence.

From 35mm color slide.

In contrast, the AIDS Memorial Quilt was created to foster understanding and acceptance of a minority population that became associated with a communicable disease that was deadly at the time. The first reported case of what would later be named AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) was in 1981. The disease (which can be transmitted by unprotected sexual contact, as well as through blood transfusions, dirty needles, transplants, and other means), devastated the gay community. Indeed, a Queer San Francisco newspaper referred to it as “Gay Men’s Pneumonia.”[23] It peaked in the early 1990s, and by 2000, almost 450,000 people died of it in the US alone, a highly disproportionate number of whom were Gay men.[24] Many figures in positions of high power — particularly in the administration of then-president Ronald Reagan, which treated the disease as if it were a joke, disregarded the disease and its devastating effects while openly displaying their homophobia.[25]

Cleve Jones, a gay rights activist in San Francisco, founded the NAMES Project Foundation with a group of friends to memorialize all those they had lost to this disease. This was not designed to be a private memorial, though — far from it. In 1987, during the National March for Gay and Lesbian Lives, a group of volunteers from the NAMES Project Foundation displayed a quilt made from 1,920 panels on the National Mall in front of the U.S. Capitol Building.[26] This installation of textile art displayed the names of LGBTQ+ people who had died from AIDS. As Julie Rhoad, a later president of the NAMES Project wrote:

Cleve Jones wanted the Quilt to be a weapon. A weapon that said, “we are going to break the barriers of stigma; we’re going to fight homophobia.” In ’87, bearing witness to that display was a remarkable moment. Two thousand panels of the AIDS Memorial Quilt arrived on the National Mall where they were not welcome, and they provided visual evidence that [these people] were actually loved by moms and dads, by heterosexuals no less.”[27]

After this first installation, the quilt toured the country to raise awareness of the scale of devastation the AIDS epidemic was causing to families, friends, and lovers.[28] The quilt gained panels as it toured, and raised money for AIDS support. The above photograph from 1996 shows the final display of the installation in its complete form, again on the National Mall, where the project began. By 1996, the quilt had grown to 40,000 panels. Today the AIDS Memorial Quilt has almost 50,000 panels that include the names of more than 110,000 people who have died from AIDS.

Each panel is made from multiple smaller pieces that contain the names of the dead, along with images and text that celebrate each life. Names are scrawled in marker, embroidered, appliqued, and sewn on in buttons. Some squares are made by experienced quilters, but most are made by novice artists, which gives the installation considerable emotional weight. The domestic form the memorial takes recalls the act of caring for someone or being cared for. A quilt is what a grandparent might make for a baby grandchild, and it can be the blanket that covers a body after death.

The AIDS Memorial Quilt is a powerful use of art to sway public opinion during a deadly epidemic. The shocking size of this memorial is meant to impress on the viewer how many people have been affected by the death of someone with AIDS. The quilt resembles a graveyard laid out in a grid pattern in front of the Capitol Building. The quilt was part of a larger effort, including AIDS walk-a-thons and other efforts, to educate the wider public about the disease and its devastating consequences. These eventually changed public opinion and public policy, and laid the groundwork for both medical and legal protections for members of the LGBTQ+ community — and for everyone else, as this disease is indiscriminate, and anyone can, of course, contract it.

Many cultures personify death, thereby giving this abstract force a body and even, at times, a personality. What should death itself look like? Plague, an 1898 painting by Swiss symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin, shows one such physical embodiment of death. Here, death rides through a narrow city street atop a winged dragon-like creature that exhales clouds of disease. In this large painting, which is almost five feet tall, a horrifying figure looms over the viewer, due to its placement high up on the central axis. A trail of smoke and devastation fills the background. The townsfolk are overwhelmed with grief and agony as they collapse in the street. These elements work together to create a suffocating feeling within the painting, as if death and disease are closing in on the viewer.

At the time of Plague’s creation, the Black Death or bubonic plague had not been seen in centuries, but Europe was experiencing widespread deaths from cholera and typhoid fever, both of which affected Böcklin personally. He lost six children in his lifetime, two of whom died from each illness.[29] Böcklin painted this work in his seventies, while struggling with illness and declining health, and he died before finishing it. Death was very much a looming presence in his life. Within Plague, it’s clear to see the inevitability of death, and the fear associated with it. Through Böcklin’s portrayal of Death, though, we can understand his perception of death as an impartial force. In his depiction, it is clear Death — hollow-eyed, gaunt, and grey-green — takes no pleasure, nor has any remorse; though it leaves a trail of desolation, it is merely an irresistible force of nature.

While works of art like the AIDS Memorial Quilt can memorialize the large-scale effects of deadly diseases, art can also express individual and personal tragedies. Tuberculosis (TB) has not always been an easily treatable disease. In the nineteenth century, TB was a leading cause of death in Europe and North America, killing one in seven people. It caused devastation all around the world, and was depicted in many different ways in artwork. Cristóbal Rojas Poleo approached this sorrowful subject through a depiction of an individual loss. His The Misery (1889) depicts a husband sitting next to a bed in which lies his wife, recently dead of TB. His face is distorted into a complex, ambiguous expression that seems to contain shock, anger, and grief. The palette of the painting is limited to dull, muted, even sickly colors, but for the ruddy tones of the husband’s face and hands, which suggest his sturdy health, in sharp contrast to the yellowing, waxy skin, painted with green undertones, of his dead wife. His gaze is unfixed, unseeing.

The sparse state of the room — with rickety furniture, bare, dirty, stained walls, and worn wooden floors — indicates that the couple is poor. The bedding is frayed and tattered, suggesting that they can’t afford even simple necessities. Perhaps the man’s anger and frustration reflect the knowledge that poverty was a leading cause of the spread of TB, and also would have prevented them from affording the care needed to save his wife’s life. Here, then, tragedy sits upon tragedy, sorrow on sorrow.

The invention of photography created a new way for grievers to memorialize the dead: postmortem photography.[30] Also known as death portraits, these images became increasingly popular as Victorian nurseries were plagued with many diseases like measles, scarlet fever, rubella, and diphtheria, all of which could be fatal for infants and children. While these death portraits might seem morbid to many people today, when photography was new, uncommon, and expensive, these images were often grieving parents’ only pictures of their beloved children.

This photograph depicts a pair of twins. One appears alive, with softly open eyes. The other, whose eyes are closed, is surrounded by flowers, indicating that this baby has passed away. In early photographs, which required long exposures, the dead are often captured in sharper detail due to their lack of movement, while the living tend to be a bit blurry due to their motion. The photographs, unsettling though they might be, give a sense of love of a mourning family for the family member they have lost.

Crossing Over: Funeral Rites and Rituals

The belief that souls cross over into an afterlife is fundamental to many cultures, and is often reflected in art. The Dogon people of the Sangha region in Mali exemplify a serious approach to this task. They hold a funerary feast service for Dogon men spanning six days, referred to as Dama. For elements of this feast, Dogon dancers wear costumes and masks. Kanaga masks are the most popular of these, and those who put them on “cavort, jump, and twirl on the stage in small groups,”[31] performing dances that “prove themselves real sagatara, strong young men, which is why this mask is so popular”[32] (see here for image). The Dogon people believe that dancing while wearing a Kanaga mask aids the spirit of the person who has died to cross over into the afterlife. The effort to move a soul to rest with the ancestors is also intended to protect the village, ensuring the safety of everyone living there by making sure that the spirit is not lingering and causing problems.

Members of the Awa group, a society of men holding ritual and political power in Dogon society, organize the Dama and make and wear all ceremonial masks. Awa has influence over many practices, including funerary rituals. The Kanaga masks — made with natural dyes and organic materials like wood, fiber, and hide — stand tall, with red and yellow tassels hanging down to cover the backs of the dancers’ heads. The faces of Kagana masks are rectangular, with two vertical indentations pierced with triangular shaped eye holes. As the dancers move, the masks move too, so the motion of the masks contributes to the production of the dance. The masks serve a crucial role in the Dama and stand apart from other ceremonial masks. A key element to identify a Kanga mask is the double-barred cross. This is always above the face, with elements attached to the horizontal lines.[33] One theory is that this is representative of both creation and regeneration.[34] Another theory is that the bars are representative of serpents. This suggests a connection with a myth of the origin of death, which states that originally, instead of dying when the time came, elderly community members would travel to the countryside to transform into serpents, to live eternally in their new form.[35]

Many cultural practices indicate a desire for connection with a spirit world. This is often seen through funerary rites and rituals. The post-funerary Malagan service of the people of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, is a feast celebrating the life of a community member who has died.[36] Artisans spend a vast amount of time in preparation to make figures for the ceremony. The craftsmen are also community members familiar with the deceased person’s clan.[37] Malagan ceremonies are the last celebration to take place within their funerary service, after the completion of the mourning period. The ceremony can happen years after the person’s death, which allows the artist working according to the clan’s directions time to create the figure, which then stands in for the deceased individual during Malagan, acting as a skin for the spirit.

Not all Malagans look the same. Some are poles, like this one. Others are masks, woven circular mats, or wood boards. Some are even dugout canoes that typically have a carved figure inside. Whatever the design, they all serve the same function: a skin for the spirit during the end of their funerary service. They thereby allow the dead person to attend their own celebration as the guest of honor, while the community collectively commemorates them. The Malagan figure is discarded or dismantled at the conclusion of the ceremony. This act is crucial and holds an array of symbolism. Malagans serve solely for a single Malagan service and are discarded thereafter. Dismantling the figure reflects the process of death and decay.[38]

Organic materials — wood, pigment, vegetable fiber, and shell — are all used to make Malagans. Since the figures are to be destroyed, the materials are natural and local, down to the red, yellow, and black details that are made from natural pigments. When the Malagan breaks down, the materials reenter the earth. This process mirrors that of the deceased’s cycle of life and death.

Malagan figures contain symbolic imagery tied to the clan’s religious beliefs, including representations of specific ancestors. The head at the bottom of this figure, for example, is a rock cod, a type of fish that is protandrous, meaning that they are born male and then become female as they age, which the people of New Ireland see as symbolic of the matrilineal structure of their community.[39]

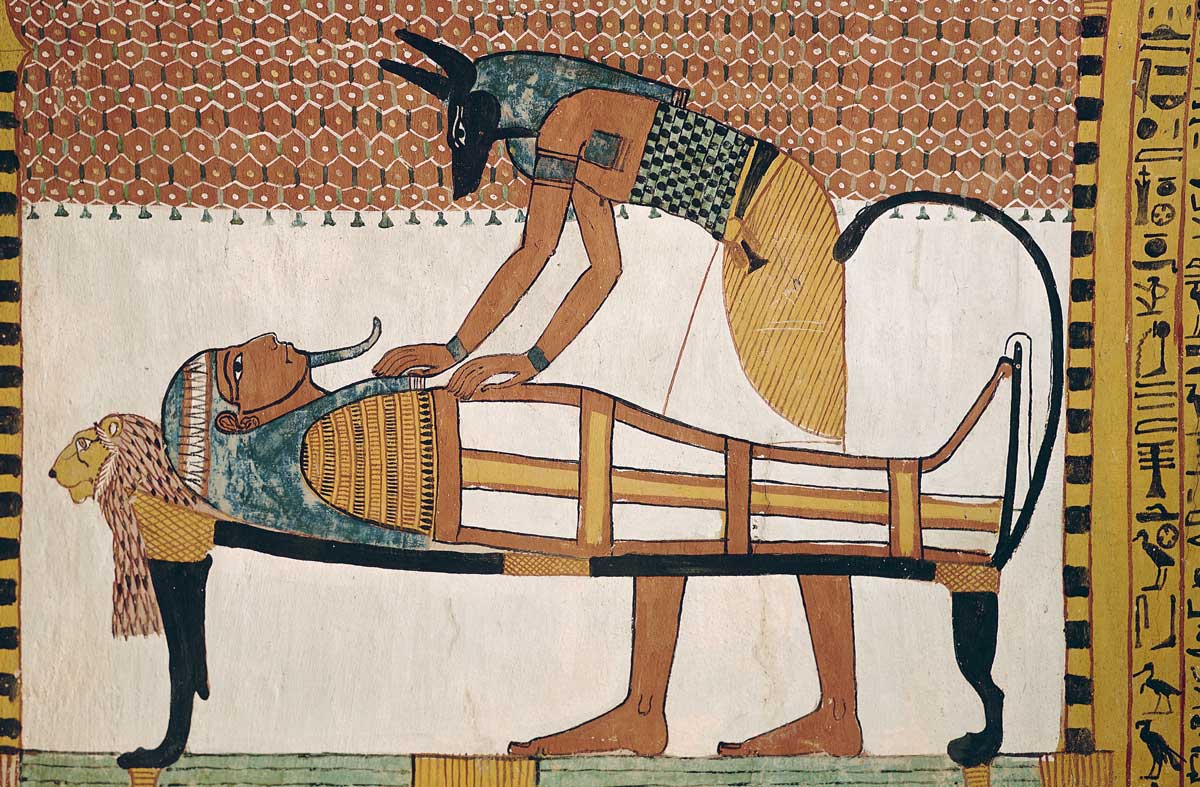

Much of ancient Egyptian religion — most famously — was dedicated to preparing the dead for their journey into the divine world they believed existed after death, and providing for them once they had successfully arrived. Egyptians believed this required correct performance of rituals, including burial ceremonies, which they believed were presided over by several deities, such as Anubis, god of funerary practices and care of the dead. He is depicted, as in this image, with the head of a jackal on the body of a man. In the earliest myths, Anubis ate the dead — as jackals do — but eventually he came to be seen instead as an important figure in the process of conducting souls to the afterlife, and was credited with embalming the god Osiris, lord of the dead, and thereby creating the first mummy.[40]

Here, we see Anubis preparing Sennedjem in an image that decorated a wall of a tomb housing the bodies of Sennedjem, his wife Iynefert, and their children and grandchildren.[41] Inscriptions identify Sennedjem as a “servant in the place of truth,” a title given to the workers who constructed the important tombs of the pharaohs in the Valley of Kings. It is possible that Sennedjem and his family and their co-workers built and decorated this tomb, which is unusually lavish for people who were not royalty or nobility.[42]

The hieroglyphic text that accompanies this image identifies Sennedjem as a fierce supporter of Osiris who fought for him in his life, and asks that all those deities who attend to the rituals of the dead help his ba, his soul, enter into the House of Osiris. This image was part of a large-scale program of texts and images that covered the walls of Sennedjem’s tomb. Just beside it, Anubis appears again, now leading Sennedjem to meet Osiris and be welcomed into the afterlife.[43]

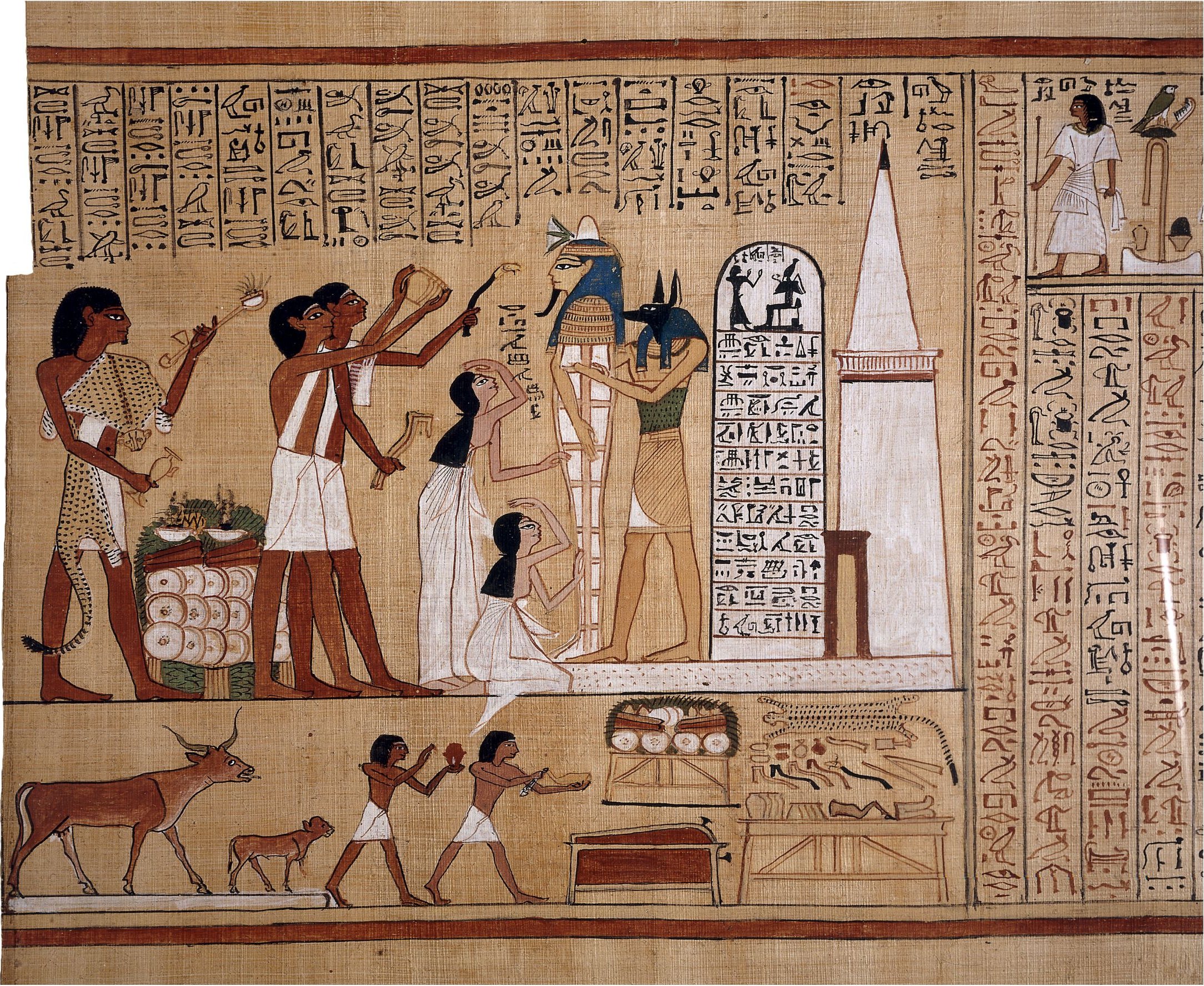

In addition to a tomb, and the sarcophagus it contains, ancient Egyptians believed that the dead needed a copy of the Book of the Dead to be buried with them. This book, written on scrolls made of papyrus reeds, was intended as a manual on how to get to the afterlife by successfully passing through a series of trials. Many books of the dead existed, with authors varying the content. The earliest known versions of these texts are the so-called Pyramid Texts, which had been only available to royalty and consisted of spells and prayers meant to protect the dead in the afterlife. Eventually, the texts were available to any who could afford to have a scroll of the Book of the Dead produced for them, but these remained only affordable to wealthy individuals.[44]

This specific image depicts an Opening of the Mouth Ceremony. There are multiple figures presenting objects towards the mummy of Hunefer, a scribe and administrator to a pharaoh. It is possible that this royal scribe wrote the text of this copy, with which he would eventually be buried. The image shows the mummy’s white linen wrappings as well as the mask, which may be presented with gold paint. As with the image of Sennedjem’s mummy, again we seem to see the jackal-headed Anubis attending to the details of the ritual, but scholars now believe that this image is intended to show a masked priest dressed as this god.[45] During the ceremony, various gestures would be performed on the corpse that were believed to bring life back into it. One of the most common actions was for priests to touch the face of the corpse with sacred objects. In Hunefer’s book, such sacred artifacts include a vessel, scepters, and a pipe. The purpose of doing such was to stimulate the functions and senses of the mummy: breath, taste, sight, and so on.[46]

This work utilizes contrasting colors in order to emphasize the focal point: the mummy. A majority of this piece is in warm shades of beige (the color of the unpainted papyrus and the female figures) and brown (for male figures). This makes the cool blue of the mummy mask — probably intended as a reference to the rich blue stone lapis lazuli — stand out. The contrast is further accentuated by the brightest parts of the piece being directly around the mummy. The figures extending their offerings also draw our attention to Hunefer by creating a series of implied lines from their arms towards his head. He is also presented in hieratic scale, depicted as larger than all the figures including the priest dressed as Anubis, standing behind him.

Across several images, this scroll depicts the full process of Hunefer’s successful induction into the afterlife. It would have perhaps been a comfort for him during his life, and was seen as essential for his soul after his death. Each aspect of the burial ritual had to be conducted correctly for him to enter into the eternal joy that ancient Egyptians believed would await the virtuous in the next world.

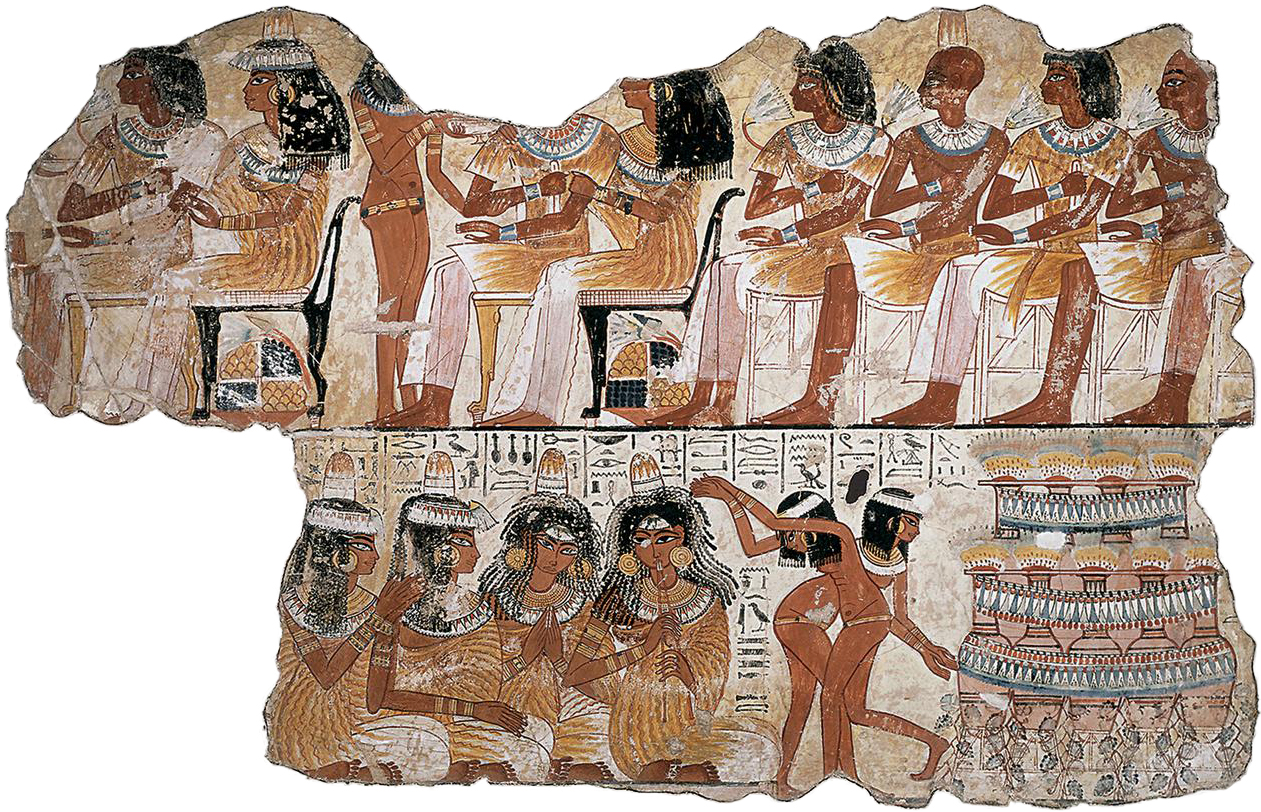

A tomb painting showing the funerary banquet of Nebamun, another high-status scribe and official, offers a vivid window into ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife, where death is seen not as an ending but as a gateway to an idealized existence. This work shows a grand banquet meant to bring Nebamun eternal comfort and joy. Such scenes, full of feasting, music, and dancing, were common in tombs to ensure that the deceased could enjoy earthly pleasures forever. Egyptians believed that the afterlife continued the best parts of life, where joys were enhanced and made eternal. By including these scenes, the living aimed to provide for the deceased’s needs in the next world.

The painting captures both the physical beauty of the event and the idea of a perfect world beyond, where earthly pleasures are everlasting. Musicians and dancers are arranged in two registers, evoking a sense of joy intertwined with the theme of death. In the upper register, men and women sit together, attended by a standing servant-girl, symbolizing their continued presence in the world beyond. The lower register features four musicians — two presented in a rare full-face view — seated on the ground as two dancers perform, bridging the gap between the living and the deceased. A neighboring panel depicts more musicians and the hieroglyphs above them provide the lyrics of the song the sing:

The earth-god has caused

his beauty to grow in every body…

the channels are filled with water anew,

and the land is flooded with love of him.[47]

Enriched by fifteen vertical registers of hieroglyphs, the scene adds layers of cultural significance that emphasize the afterlife.[48] The figures are painted in vibrant colors, with overlapping forms that suggest a communal bond that transcends mortality. Throughout the tomb’s imagery, Nebamun is depicted with particular prominence, symbolizing his enduring status and reflecting the Egyptian belief that the afterlife is a joyful continuation of mortal existence,[49] allowing him to experience a world filled with happiness, prosperity, and harmony forever.

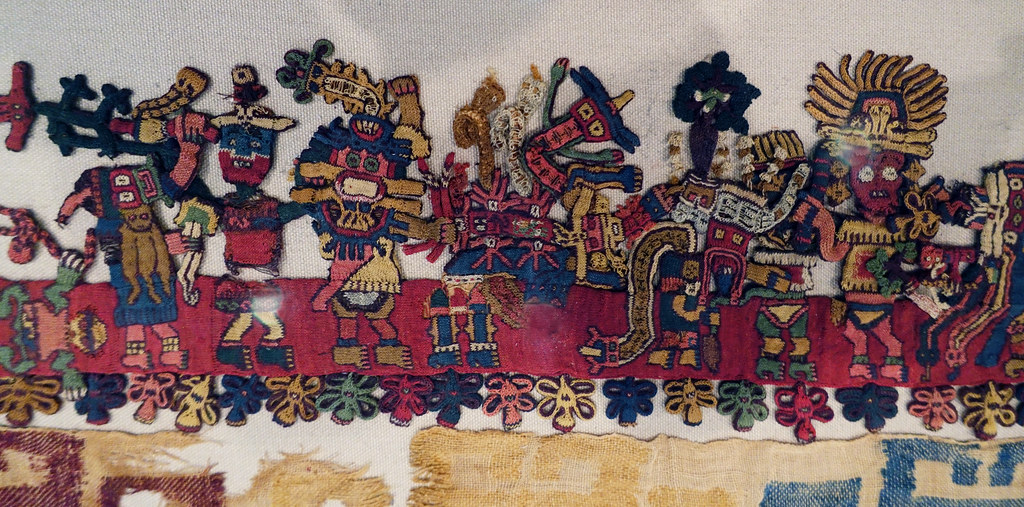

Although death is often perceived as a finality, an end-of-life event, Egyptians were not along among ancient (and modern) cultures in viewing death as a transformative transition to new life. In the early twentieth century, three burial sites were excavated on the Paracas Peninsula along the coast of modern Peru. Archeologists had found the Necropolis of Wari Kayán, containing hundreds of mummy bundles, which are seated, mummified bodies wrapped in masterfully woven textiles.[50] The Paracas culture had no written language that has survived, as was common in Ancient Andean cultures. What information we have therefore comes from their beautiful architecture and artifacts, which bore great spiritual significance to the people who created them. The symbolism of the burial arrangement and the elaborate designs on textiles used in them suggest their purpose: a restoration of life through “mythic transformation” from corpse to member of the ancestral community.[51]

In total, 429 bundles were excavated at Wari Kayán, 65 of which contain particularly elaborate artifacts and textiles, suggesting a social hierarchy in which social leaders are bundled with more wealth.[52] The bundles consist of many layers of woven textiles and garments wrapped around the mummified bodies. They are placed in mass burials, forming a community of the dead. Food offerings of yuca, peanuts, and maize surround the bundles, suggesting a belief that bodies required — and could bring — sustenance into the afterlife, contributing to the ancestral community and land with nutrients. The symbolism of this offering could describe “the deceased as a fertile producer or controller of different zones.”[53] This motif of the corpse as a “fertile producer” can also be seen in the seed-like shape of the bundles themselves. The mummies are wrapped in layers and buried much like seeds planted in the earth, whereby the corpses might become growing ancestors and providers. The wide variety of garment sizes that wrap individual mummies could also reflect this. Ranging from miniature (9 cm long) to gigantic (34 m long),[54] they suggest the growth of the corpse, its transformation into a mythical ancestor.

The textiles that wrap the mummies contain repeated figures and symbols that support the motif of death as a transformation and nutrient to the ancestral community. Multispecies hybrid animal figures and repeated geometric designs suggest that the imagery exists not in reality but among “the spirit realms”[55] after death. One such image, for example, shows a figure that twists its body backward, grimacing, resembling a corpse.

These back-bending figures are often shown as part of a series of transformative mythical animal figures with overlapping traits. Across many textiles, the figures bend forward, acquiring head ornaments and tunics until they stand straight, creating a sequence and demonstrating a gradual transformation.[56] The bent, skeletal figures transition into mythical animal hybrids in elaborate costume, surrounded by plantlike motifs and seeds, representing the transformation of the bundled corpses after death into the ancestral community.

The skeletal figures are often depicted with a blade, which, coupled with their vulnerable back-bending position, implies bloodletting and self-sacrifice.[57] This likely has ritual significance, along with being representational of “fertile fluids”[58] in the form of blood, supplying nutrients to the ancestors.

Although no written primary source confirms these theories regarding the belief system behind the Paracas Mummy Bundles, common symbolism throughout the textiles and necropolis burials reveals a convincing explanation. Death was seen as a provider of new life, a transformation, and a nutrient to the ancestors. It was, to their creators, a transition to a new community, “reinforcing the individual’s contribution to society and spirituality,”[59] rather than a grim, sorrowful fate.

Unlike the embalmed mummy burials of ancient Egypt, designed to house the souls of the dead for all eternity, or the Paracas mummy bundles of ancient Peru, which preserve the dead as part of their journey to a spirit world, in Hinduism, the dead are often cremated. The Cremation of Peshwa Madhavrao I (officiated 1761-1772) and the Sati of his Wife Ramabai is a tragic piece. The work depicts a Hindu funeral rite called antyesti. The antyesti is the last samskara, or event, of a person’s life. In this practice, the body of the deceased is cremated on a funeral pyre, usually within a few hours of their death. Before the body can be cremated, it is cleaned and adorned with flowers. While the fire is being lit, mantras are recited to guide the body parts of the deceased back to their respective deities.[60] Once the body and pyre are prepped, the body is carried by friends and family to the cremation site. The purpose of the cremation is to return the dead to the elements from whence it was born. Around three days after cremation, the ashes are then spread over a sacred river. For ten to thirteen days after spreading the ashes, the family of the deceased is considered impure and must not partake in pleasure-seeking activities.[61]

The particular antyesti depicted in the image is that of Madhavrao I, ninth Peshwa — prime minister — of the Maratha Confederacy. The Maratha Confederacy was a political group started in 1674 in India to challenge the reigning power, the Mughal Empire. Madhavrao I became afflicted with tuberculosis and passed away. His body was cremated on the bank of the Bhima river, where grief-stricken citizens gathered to mourn their Peshwa and pay their final respects. During the ceremony, Madhavrao I’s wife chose to join him on the funeral pyre and commit sahamarana — self immolation of a sati (a “‘true’ or ‘virtuous wife’”) on her husband’s funeral pyre.[62] According to Hindu belief, “she ensures him a good rebirth by wiping out the consequences of his (or his entire family’s) bad karmic actions.” Although recorded as an option in ancient epics, becoming a satī in this ritual sense has always been regarded as an exceptional rather than a usual practice for widows

The artist uses contrast between the complementary colors of the dull blue-green river and bright, carnelian flames of the pyre. This creates a focal point at the center of the piece and highlights the figures burning atop it. The river also serves an additional purpose: it creates negative space around the focal point, which provides breathing space between the hatching and detailing on the funeral pyre and the figures in the foreground. Rather than the foreground figures serving individual purposes, they seem to blend together, creating a pattern-like effect that frames the focal point. The crowd is composed of people who are young and old, male and female, humble and grand, but they are united in their outpouring of grief at the loss of their leader. Despite the onlookers being in the foreground, their scale is much smaller than that of the two figures on the pyre, further emphasizing the importance of the husband and wife being cremated. The amount of emphasis placed on the two figures shows how important the funeral practice is to the culture. The image presents the funeral as a ceremony that not only honors the dead, but also strengthens the community of the bereaved.

Not all images associated with death are grim and grief-filled, though. Many cultures have celebrations of and cheery send-offs for the dead. In Korea, such practices have traces as far back as the fifteenth century, when askkoktu (or kokdu) figures were first used as colorful ornaments for the sangyeo, or funeral bier, on which the dead is placed for funeral rituals before burial.[63] The figures were provided as entertainers, as clowns and musicians who would perform novelty acts and play songs as they accompanied the spirits of the dead to the afterlife. While their “gaiety seems incongruous with mourning, they express a culture’s deep desire that the dead enter the next world surrounded by joy — and its appreciation of the fleeting nature of all experience.”[64]

Eventually, just about all walks of life came to be represented in the form of these charming figures: “aristocrats and civil servants, soldiers, monks and wizards, servants and acrobats, women and children.”[65] The design of the figures reveals their intent. This pair has gentle, smiling faces. They seem friendly and welcoming. They are draped with brightly colored clothing, signifying their status as entertainers. Their calm, comforting vibe suggests the love and consideration that were poured into them as gifts for the deceased, to care for them on their journey into the afterlife. Few kukdu figures survive because they were traditionally burned after use, and the practice ceased in the twentieth century,[66] but those that remain are a reminder that death need not be a cause of grief.

Mummification, burial, and cremation are but three of many ways that cultures across the globe seek to handle human remains. Many of these practices are, as discussed throughout this chapter, weighted with spiritual or religious significance, often tied to notions of an afterlife. In the Cuban practice of Palo, human bones are directly utilized. Palo is a Kongo-inspired form of witchcraft that uses altars called prendas (also known as ngangas or enquisos). All prendas contain nfumbe (human bones), at least a skull, fingers, and toes. Prendas are intended to channel the power of the dead on behalf of the living. Practitioners of Palo are believed to be able to use the power of the dead to heal or harm, making Palo craft “widely feared in Cuba.”[67]

Before participating in the making or use of a prenda, one has to reach the rank of padre (father) or madre (mother) nganga. Reaching this rank requires multiple initiations, one of which is receiving a prenda made by already established padres and madres. Prendas contain a plethora of ingredients, some easy to find, some very hard. One of these key elements is a vessel to hold the nfumbe and other ingredients. A common vessel is a cauldron or clay urn. Within the chosen vessel are bones, both human and animal, different plants, and water. There can be colored powders, horseshoes, mercury, feathers, coins, silver, gold, and a wide range of other objects and materials. Everything in a prenda has a purpose and story, and each prenda looks different, though they all possess the key elements. Palo practitioners believe that, once made, prendas must be fed with blood to stay satiated, lest the dead get restless and wander, causing harm in their search for blood. Palo altars are not meant to be trifled with as they are seen as very powerful and dangerous, and even those experienced in Palo practice extreme care in using them.[68]

In stark contrast to the delicate and rather private use of human remains in Palo, the Body Worlds exhibit puts the dead on display for anyone (with enough money to buy a ticket) to see. Body Worlds is an exhibition created by German physician and anatomist Dr. Gunther von Hagens. von Hagens is the creator of “plastination,” a technique “used for long-term preservation of anatomical preparations.”[69] He and his partner, Dr. Angelina Whalley, physician and curator of the Body Worlds exhibit, use plastination on human bodies to allow the public to view real human anatomy. The cadavers are acquired from postmortem scientific donations, although it is unclear if the donors were aware their bodies would be used as models in a global exhibition instead of for medical research. The Body Worlds website frames the traveling exhibit as an opportunity to better understand how our bodies work, certain medical conditions we are susceptible to, and our limitations. Despite being advertised as an educational exhibit, some of the displays seem more of a spectacle. There are bodies posed in various ways, from swinging a baseball bat to having sex (see here for image). While these displays of how the body looks during different activities are interesting, they bring into question the ethics of how scientific donations are used, and the morality of hosting and viewing exhibitions containing human bodies.[70]

The Body Worlds’s posed “plastates” are predominantly presented with their skin removed, leaving the musculature and bones on display. A figure posed with a baseball bat is contorted, with simulated exertion, face lifted to the sky as if watching the ball he just hit fly off, forever frozen in the glory of a moment he may have never known in life. In a perhaps more troubling display (which we are intentionally not providing a link to — read to the end of this paragraph before deciding to Google it), a female cadaver is posed astride a male cadaver. Stripped not only of clothes but of skin (and perhaps of dignity), the cadavers are positioned with her back to him in simulation of an intimate scene. The muscle and tissue of her abdomen is cut open and peeled back to expose the inside of her body, so that the viewer can see the man’s penis inside of her. His hands are on her hips, and hers on his arm and knee. Her head is tilted up, the muscles of her face flayed and flared out. An ethical complication exists beyond that which applies to all these figures: since von Hagens and Whalley do not disclose the specifics of the individuals whose bodies are plastinated, posed, and placed on public view, it is unclear if these individuals even knew each other in life; it seems unlikely that they did, or that they consented to such a use of their bodies. This display, then, is built out of figures violated in death, and so raises the question of whether a display that likely enacts a necrophilic rape should exist at all, much less be toted around in an exhibit across the globe.

There is an intense irony in mimicking procreation using the dead as models. Anatomical representations of sex aren’t uncommon, as we can see in Leonardo da Vinci’s cross-section drawing of a couple having intercourse (see here for image).[71] But what makes the Body Worlds presentation stand out starkly is the use of real human cadavers. The entire exhibit displays the dead in the most dynamic ways possible, immortalizing the bodies in hundreds of vulnerable displays of humanity. Where many viewers may believe that a proper burial is the height of respect for the dead, there is something to be said for perpetuating the life they lived in motion. Still, it is not clear that any of these individuals agreed to have their bodies preserved and displayed this way. If the function of the exhibition is educational, as its advertisements often claim, and not base, vulgar, and prurient, then a similar exhibit could be made with simulated bodies that would not bear the ethical complications that come with reanimating the real bodies of the human dead.

Journeys to and from the Afterlife

Ideas about the afterlife, about what might await us after death, vary from culture to culture and period to period. Artists have been helping the viewers of their work to imagine what — good or grim! — they believed lay ahead.

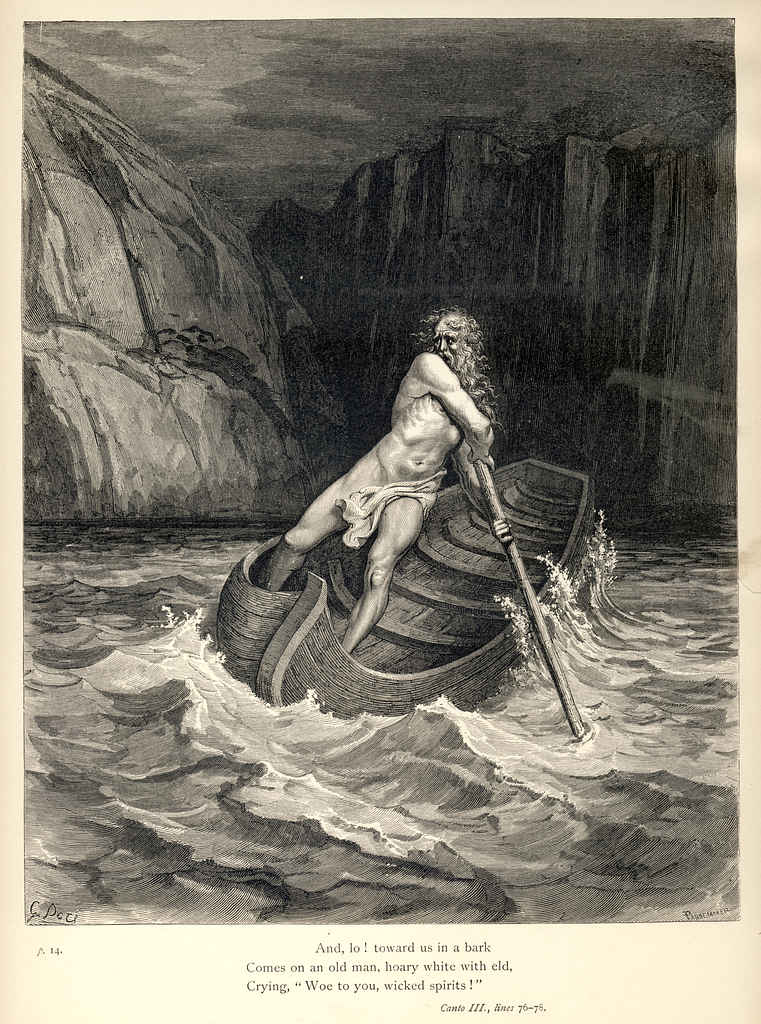

Gustave Doré’s Charon, Ferryman of the Dead (1890) is a dramatic illustration created for a translation of Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, a fourteenth-century Italian poem. In the poem, the poet is guided through a vision of the Christian afterlife, getting tours of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. His guide through Hell is the Roman poet Virgil. This “canto” opens with a description of the gates of hell, above which is inscribed one of the most famous lines in this poem: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”

This image depicts Charon guiding souls across the River Acheron, which separates the land of the living from the land of the dead — a notion borrowed from the ancient Greek myth of the River Styx. At this point in the tale, Virgil has brought Dante through the gates of hell, past a group of tormented souls and angels who did not pick a side when Satan led a failed revolution against God, up to the river itself:

Then looking farther onwards I beheld

A throng upon the shore of a great stream:

Whereat I thus: “Sir! grant me now to know

Whom here we view, and whence impell’d they seem

So eager to pass o’er, as I discern

Through the blear light?” He thus to me in few:

“This shalt thou know, soon as our steps arrive

Beside the woeful tide of Acheron.”Then with eyes downward cast and fill’d with shame,

Fearing my words offensive to his ear,

Till we had reach’d the river, I from speech

Abstain’d. And lo! toward us in a bark

Comes on an old man hoary white with eld [old age],Crying, “Woe to you wicked spirits! hope not

Ever to see the sky again. I come

To take you to the other shore across,

Into eternal darkness, there to dwell

In fierce heat and in ice. And thou, who there

Standest, live spirit! get thee hence, and leave

These who are dead.” But soon as he beheld

I left them not, “By other way,” said he,

“By other haven shalt thou come to shore,

Not by this passage; thee a nimbler boat

Must carry.” Then to him thus spake my guide:

“Charon! thyself torment not: so ’t is will’d,

Where will and power are one: ask thou no more.”[72]

Here, Charon at first refuses to take Dante across the river since he only ferries the dead to hell, but Virgil commands him to, implying that it is God’s will that he do so. In Doré’s illustration of these lines, the artist uses high contrast of light and shadow to emphasize the transition from life to death, with the nearly naked form of the ancient ferryman bright against the nearly black cliffs behind him. Charon is shown with a muscular build and a complex pose and expression as he steers the boat through dark and choppy waters. What does his body language suggest? Is he drawing back in surprise, worried by the sudden appearance of a living person in the land of the dead? And what does his presence suggest about the land of the dead? Here, all seems stormy and foreboding, but then, of course, Dante enters the afterlife in hell, and this gaunt, alarming figure of Charon is therefore a fitting indication of what awaits on the other side of the river.

While in Dante’s dour Renaissance poem, the narrator is unique in his experience of moving between the lands of the living and the dead — hence Charon’s alarm at his presence — in other stories and cultures, this would be far less exceptional. Celebrants of the widely celebrated Mexican holiday of Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead (November 1st and 2nd), for example, believe that, on these days, the spirits of those who have passed on are able to return to our world. The holiday originated as a combination of the Christian holiday of All Soul’s Day, brought by Spanish invaders, and ancient Aztec customs. The Aztecs believed that when someone died, their soul lived on the land of the dead, or Mictlán. Here, they would undergo many trials to reach their final resting place. Surviving family, friends, and community members would make altars as a means of supporting the deceased on their journey. On these altars, they would leave offerings of items they believed necessary for the soul’s survival, such as food and drinks, images, and flowers.[73]

The practice of leaving offerings continues in modern Mexico (and elsewhere), and is included in traditional Día de los Muertos celebrations. Now, though, these are more often items meant to welcome these spirits back to the land of the living. Ofrendas, or altars, traditionally include the deceased’s favorite foods, candles, and any other items with personal connections to the loved one. Oftentimes, marigolds will also be placed upon the ofrenda and the path surrounding it in the hope that these bright flowers will help guide spirits on their journey to the land of the living. Ofrendas are used as a way to remember those who have passed and to allow their memories to live on.

La Ofrenda (The Offering, 1931), by famous Mexican painter and muralist Diego Rivera, consists of three figures respectfully surrounding a small white altar (see here for image). Two of these figures sit on their knees, with their hands clasped in their laps, looking off into the distance as they pray before the altar. The third figure faces away from the altar mournfully and allows the other two figures to have a private moment to pay their respects to their deceased loved one. On the altar sit objects that we can assume were meaningful to the spirit that is being welcomed. The figures are overwhelmed by masses of greenery, highlighted by a chain of marigolds draped across a prickly pear cactus. The composition of the greenery creates a continuous path that is representative of the circle of life, which includes the marigolds, which guide spirits between the land of the living and land of the dead. This composition refers to the connection that unites the living and the dead.

Embodiments of Death

Many cultures create embodiments of death, either as deities or as the force itself. While some of these are malevolent or implacably neutral, there are benevolent gods of death such as the Hindu Yama. A nineteenth-century depiction of Yama shows the god as a humanoid with blue skin, riding a buffalo. In two of his four hands are his weapons of choice: a mace and a noose that he uses to bring souls into Patala, “the seven treasure- and wonder-filled subterranean worlds.”[74] His secondary pair of arms holds the reins of the buffalo and a trident. He wears a golden crown and golden clothing embroidered with many gems along the front and sides. Perhaps most importantly, he wears a calm, benign expression on his face. He appears a welcoming and helpful figure, not an agent of divine wrath.

Yama is a very important figure in Hindu mythology (and in Buddhism, as well). According to the ancient Rg Veda (“Knowledge Consisting of Praise Verses”), Yama was the first person to die, and therefore became ruler over Patala and a guide for the dead when they pass on.[75] He uses the Book of Destiny to determine if they will enter one of the pleasurable or harsh realms of the dead. When a person has performed many good deeds, they are brought to heaven and then reincarnated in a higher class; those who have not are brought to hell and then are born into a lower class in the next life. As a benevolent god of death, Yama remains an important figure in Hindu culture. Here, the personification of death is very lively and colorful, implying his role in the cycle of life, death, judgment and reincarnation into new life.

Mictlantecuhtli, the Aztec god of death and ruler of mictlan, the “restful and silent kingdom of the dead,”[76] bears some similarities to Yama in function, but representations of him are strikingly different. A stone figure carved around 900 CE presents Mictlantecuhtli as a hunched skeleton, seated on his haunches, with his arms crossed over his knees. The figure is adorned with a tall headdress to indicate high status. Mictlantecuhtli’s expression is menacing, with a toothy smile and round, bulging eyes set in deep, sharp-edged sockets. The artist places emphasis on the headdress and eyes by exaggerating their scale in comparison to the rest of the figure, adding to the foreboding nature of the statue. Statues like these were made as offerings and for rituals performed to appease the god in the hope that their maker or patron would enter paradise when they die.

However, Mictlantecuhtli is not only a god of death; like Yama, he is also a god of life and “appears as a protagonist in scenes referring to penetration, pregnancy, the cutting of the umbilical cord, and lactation.”[77] Death and life were, in Aztec religion, cyclically interconnected. The bones of the dead functioned as seeds, and the god Quetzalcoatl, creator of humans, was believed to travel to the underworld to steal the bones of the dead to use to create new humans. The Aztecs performed rituals they intended to help souls return to the earth after a journey through the underworld. They believed that the souls of the deceased must make a four year journey in order to be reincarnated. Rituals to aid in this process included offerings and the burning of incense, but also the consuming of the flesh of a person sacrificed while serving as an impersonator of the god. Since this was considered a heroic death in Aztec culture, the sacrificial victim was supposed to be granted a place in the underworld, since a person’s place in paradise or the underworld was determined by their death, not their life.[78]

Human Sacrifice in Art

The ritual of slaughtering an animal or human as an offering to please or appease a god or other supernatural figure was common in the ancient world, and continues — at least in terms of animal sacrifice — into the present. Sacrificial imagery appears in works of art throughout the world, and across time.

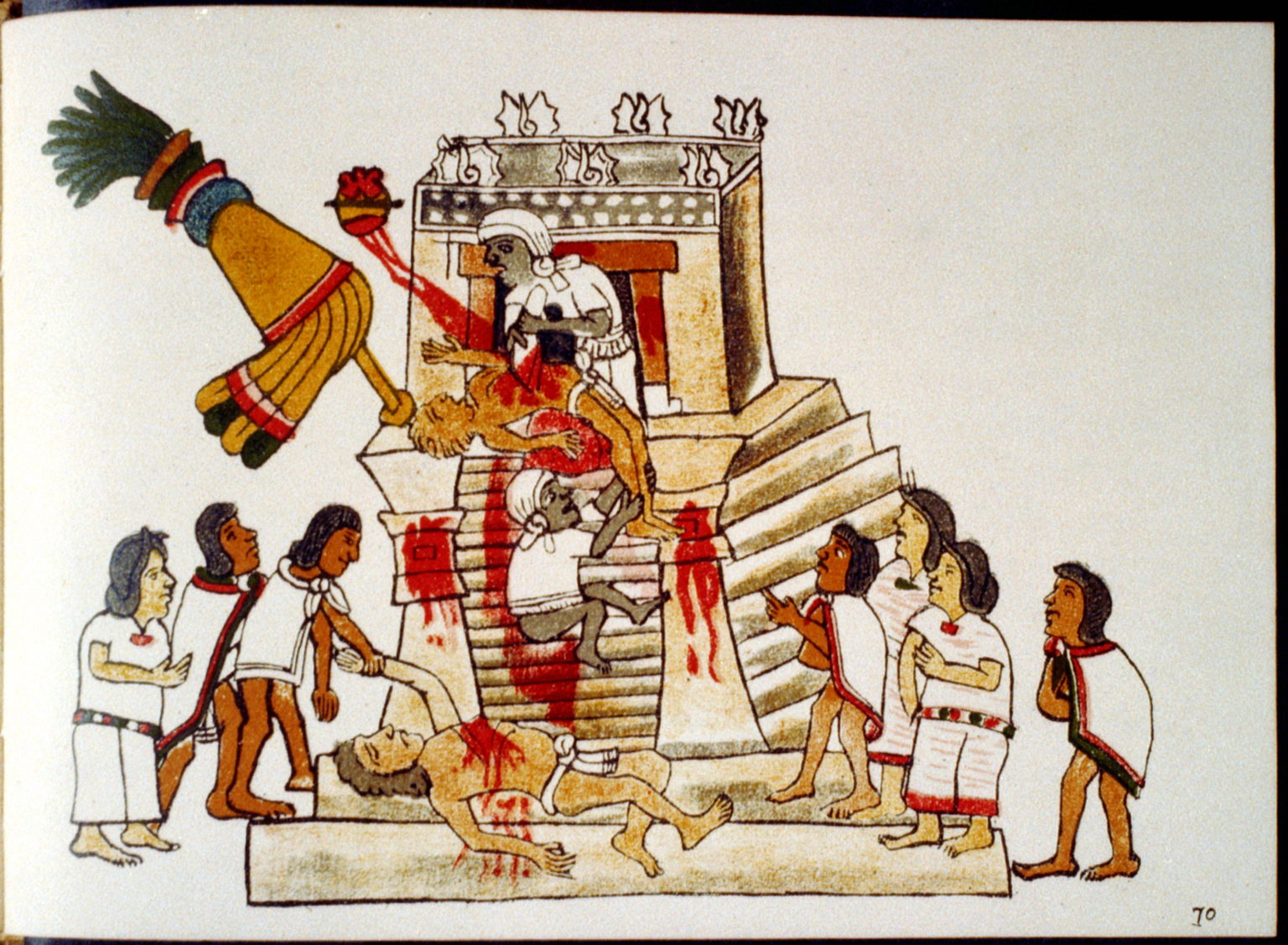

The Codex Magliabechiano is a collection of cultural data on Mesoamerican life, created by Spanish Christian priests working with conquistadors — Spanish and Portuguese conquerors, especially those who invaded and colonized much of the Americas — and indigenous artists. (The whole manuscript is available online.) As art historian Elizabeth Hill Boone summarizes the process, “Sometime between 1529 and 1553… a mendicant friar proselytizing among the [Indigenous groups] in Central Mexico requested a native artist (or perhaps several) to paint for him images showing the native deities, calendars, and customs.”[79] The “codex,” which is simply a formal term for a physical book, was created around 1566. Among other practices, it documents the Aztec practice of human sacrifice, which is also suggested by archeological evidence.

The Aztecs have long been associated with lurid tales of human sacrifice, often described as if they were somehow unique in this practice, though evidence exists of human sacrifice throughout the premodern world, from China to the Middle East to the Americas.[80] Tales about the Aztecs are frequently based on Spanish accounts that, while not wholly invented, bear the strong imprint of bias and self-serving motives. Scholars have argued that “the conquistadors made much of the practice not from a horror of it as much as because it provided an excuse for conquering.” If an Indigenous person was, according to conquistadors, “guilty of the heathen practice of human sacrifice, it was perfectly lawful to take his gold and, if he resisted, to fight, kill or enslave him.”[81]

The images of human sacrifice in the Codex Magliabechiano are particularly explicit. The artist who created this scene presents the ritual as gory and blood-soaked: a group looks on as a sacrificial victim is held down while a priest rips out his heart. Below them, a person drags away a second body from which the heart has been removed. The figures conducting the sacrifice are grey, likely a representation of the body paint worn by priests, which:

consisted of all kinds of poisonous animals (scorpions, spiders, serpents etc.) which were burnt, after which the ashes were compounded and mixed… with the piciete [tobacco] and ololiuhqui (Morning Glory). Smearing this ointment on the body enabled the priests to see the gods and to communicate with them.[82]

The figure performing the sacrifice is an Aztec priest, and the sacrifice is for the war and sun god Huitzilopochtli. The victim’s heart is floating up into the sky, presumably toward Huitzilopochtli.