Introduction to Stasis Theory

4 Modifying Stasis Theory for the Classroom

by John R. Edlund

I recently had a discussion with one of my ERWC colleagues about the proper way to use stasis theory. The technique develops out of courtroom practices and is used primarily to locate the points of disagreement so that a trial can proceed efficiently. In this forensic use, the parties are debating the nature of a past act and what should be done about it. The process can be modified a bit to deal deliberatively with the effectiveness of a particular policy on future conditions. In either case, the first step is to get the parties to agree on the question at issue, a process which is called “achieving stasis.” Then the stasis questions are used to figure out where the disagreement lies. The result is a lot of clear thinking and efficient progress towards a resolution of the problem.

The problem for teachers and students in the application of this process is that we are not in a courtroom trying a case or in a deliberative body deciding whether or not to implement a particular policy. Instead, we are using stasis theory as an analytical tool to get to the heart of a social issue or personal problem. We have to modify the tool a bit to make it work in the classroom.

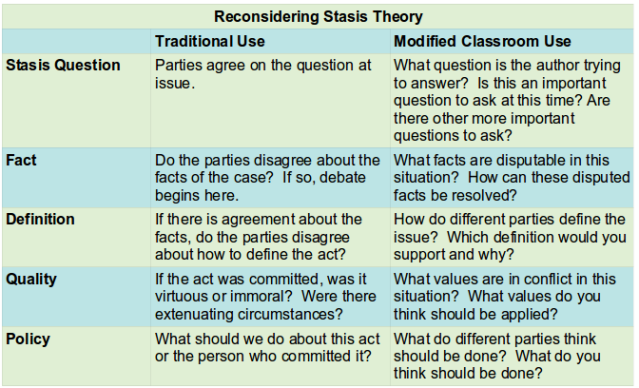

Achieving stasis by agreeing on the question under discussion is an important first step. However, as my colleague pointed out, in an ERWC module and in general when we are discussing several texts on a particular issue, it is rare that the authors have defined the issue in the same way. They are often answering different, but related questions. Stasis theory helps us see that, but we do not have the power to bring the authors together to agree on the question. What do we do? I have summarized our discussion in this chart:

As noted in Figure 4.1, one approach is to tease out the questions that the authors are really trying to answer and analyze the differences that result when we try to apply the stasis questions to each approach. This would bring considerable clarity to the discussion and would make a good paper in itself. This process might begin by asking of each author, “What question is he or she trying to answer?”

Another approach is for the student (or the teacher) to pose the question that they think should actually be asked and then use the stasis questions to explore how the different parties to the discussion disagree. For example, on the Declaration of Independence, I might ask the following stasis question:

Did George III actually do all of the terrible things of which he is accused in the Declaration of Independence?

Possible responses might be

- Fact: The parties actually disagree about this. The British say that these alleged “crimes” are all acts of parliament. The British would actually be right about this and Thomas Jefferson knows it. They are scapegoating the king for rhetorical effect and to address the problem of declaring themselves no longer subjects of the king. They have to make the king an unfit ruler. But nobody really disagrees that these things have been done.

- Definition: The colonists say these acts are examples of tyranny, while the British say it is just governance.

- Quality: This really comes down to intentions. The colonists say that these tyrannous acts are designed to hinder and control self-governance in order to hamstring the colonies and keep them from becoming independent and powerful. The British say that they are governing the colonies and protecting them from harm.

- Policy: The colonists say that such acts justify rebellion. The British wage war in response.

If we try a more philosophical question such as “Are all men (and women) created equal?” we see that things get interesting and complicated very quickly. The British immediately say, “You’ve got to be kidding. You are a bunch of slave holders.” Then we are going to get into race, social class, economic inequality, land owners versus renters, cultural practices, and a host of other things. What the founders meant was that they were going to get rid of the nobility, that there would no longer be lords and commoners. The British say, “Good luck with that.”

When it comes to definition, we might say that the Declaration is “aspirational” in that it proposes ideal principles that the colonies have not yet achieved. The British call the document “hypocritical.” On the face of it, the British are right. It does seem hypocritical to say that “all men are created equal” while holding slaves. Questions of quality are going to hinge on those definitions. Does the Declaration represent aspirational idealism or hypocritical self-interest?

About policy? Well, the aspirational view won out and we ended up with a constitution. We are still trying to meet the principled ideals of the Declaration, but we have made progress.

One of the new modules to be introduced in ERWC is built around a novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon. It is a murder mystery, which would seem to make it ideal for the application of forensic stasis theory. However, in this case, we are doing literary criticism and exploring some of the issues raised by the novel (Full disclosure: I haven’t read the novel yet. I am guessing from the Wikipedia entry and a picture of the cover). One question in the story is “Who killed the dog?” The stasis questions might lead to some larger philosophical and ethical issues:

- Fact: A dog is dead. Did someone kill it?

- Definition: Is killing a dog murder?

- Quality: Was killing the dog necessary because it was mean, sick, or dangerous? Or was it an act of revenge or cruelty?

- Policy: Should dog murderers go to jail?

Here, the stasis questions are helping us define one of the acts in the novel.

One of the questions that came up in our discussion was “Can you use the stasis questions as an invention strategy or brainstorming tool to generate lots of possible questions to explore?” As I noted above, we have to modify the stasis tool because we are not in the same situations for which it was originally designed. Use as a sort of focused brainstorming tool is certainly possible. In that case, we might ask

- What facts are disputable in this situation?

- How do different parties define the issue?

- What values are in conflict in this situation?

- What do different parties think should be done?

There are lots of ways to use stasis theory. In almost any situation, it will help us think about questions, facts, definitions, values, and policies.

Attributions

”Modifying Stasis Theory for the Classroom” by John R. Edlund is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Feedback/Errata