Research Writing in Academic Disciplines

17 Ethics and Documenting Sources

by Michael Beilfuss

General Principles

In day-to-day life, most people have a sort of sliding scale on what constitutes ethical behavior. For example, you might tell your best friend their new haircut looks attractive when in fact you believe that it does not. This lie, though minor, preserves your friend’s feelings and does no apparent harm to them or anyone else. Some might consider the context before determining how to act. For example, you might not tell a stranger that they were trailing toilet paper, but you would tell a friend. With a stranger, your calculations may include how the stranger might respond to the interruption, and both of you may feel some embarrassment in the exchange. Such calculations may make it easier for you to look away and let someone else deal with it, but with a friend, you would be willing to risk some short-term awkwardness to do the right thing.

In a far more serious situation, a person might not risk their lives to help a stranger, but they might risk their lives to help a close friend or relative. For example, if you witness a stranger attacking someone you do not know on a crowded street, you may be afraid to interfere because you could be injured in the event. Instead, you might stay back and call the police. But if a close friend or a relative was in the same danger, you may be more likely to put yourself in harm’s way to protect your friend. In this case, your commitment to loyalty might outweigh your sense of self-preservation. In the former case, if you valued physical courage above all else, you might be willing to step into a fight to protect a victim. In either case, weighing the costs and having a strong value system would help you feel like you did the right thing—especially upon reflection after the event.

Ethical behavior, including ethical technical communication, involves not just telling the truth and providing accurate information, but telling the truth and providing information so that a reasonable audience is made aware of the behavior. It also means that you act to prevent actual harm with set criteria for what kinds and degrees of harm are more serious than others.

For example, saving someone’s life should always outweigh the prospect of financial damage to your company. Human values, and human life, are far more important than monetary values and financial gain. As a guideline, ask yourself what would happen if your action (or non-action) became entirely public and started trending on social media, got its own hashtag, and became a meme picked up by the national media. If you would go to prison, lose your friends, lose your job, or even just feel embarrassed, the action is probably unethical. If your actions cannot stand up to that scrutiny, you might reconsider them. Having a strong ethical foundation always helps.

However, nothing is ever easy when it comes to ethical dilemmas. Sometimes the right thing to do is the unpopular thing to do. Just because some action enjoys the adulation of the masses does not necessarily mean it is appropriate. As such, it is important to give some serious thought to your own value system and how it may fit into the value systems of the exemplars you admire and respect. That way, you will be better prepared to do the right thing when you are confronted with a moral dilemma. Internalizing your principles in such a manner will certainly make you a more ethical writer.

Presentation of Information

How a writer presents information in a document can affect a reader’s understanding of the relative weight or seriousness of that information. For example, hiding some crucial bit of information in the middle of a long paragraph deep in a long document seriously de-emphasizes the information. On the other hand, putting a minor point in a prominent spot (say the first item in a bulleted list in a report’s executive summary) might be a manipulative strategy to emphasize information that is not terribly important. Both of these examples could be considered unethical, as the display of information is crucial to how readers encounter and interpret it.

A classic example of unethical technical writing is the memo report NASA engineers wrote about the problem with O-ring seals on the space shuttle Challenger. The unethical feature was that the crucial information about the O-rings was buried in a middle paragraph, while information approving the launch was in prominent beginning and ending spots. Presumably, the engineers were trying to present a full report, including safe components in the Challenger, but the memo’s audience—non-technical managers—mistakenly believed the O-ring problem to be inconsequential, even if it happened. The position of information in this document did not help them understand that the problem could be fatal.

Ethical writing, then, involves being ethical, of course, but also presenting information so that your target audience will understand the relative importance of information and understand whether some technical fact is a good thing or a bad thing.

Ethical Issues in Technical Communication

There are a few issues that may come up when researching a topic for the business or technical world that a writer must consider. Let us look at a few.

Research that Does Not Support the Project Idea

In a technical report that contains research, a writer might discover conflicting data that does not support the project’s goal. For example, your small company continues to have problems with employee morale. Research shows bringing in an outside expert, someone who is unfamiliar with the company and the stakeholders, has the potential to impact the greatest change. You discover, however, that to bring in such an expert is cost prohibitive. You struggle with whether to leave this information out of your report—thereby encouraging your employer to pursue an action that is not the most productive. In this situation, what would you do and why?

Suppressing Relevant Information

Imagine you are researching a report for a parents’ group that wants to change the policy in the local school district, which requires all students to be vaccinated. You collect a handful of sources that support the group’s goal, but then you discover convincing medical evidence that indicates vaccines do more good than potential harm in society. Since you are employed by this parents’ group, should you leave out the medical evidence, or do you have a responsibility to include all research—even some that might sabotage the group’s goal? Is it your responsibility to tell the truth (and potentially save children’s lives) or to cherry pick information that supports the parent group’s initial intentions?

Limited Source Information in Research

Thorough research requires a writer to integrate information from a variety of reliable sources. These sources should demonstrate that the writer has examined the topic from as many angles as possible. This includes gathering scholarly and professional research from a variety of databases or journals rather than favoring one resource. Using a variety of sources helps the writer avoid potential bias that can occur from relying on only a few experts. If you were writing a report on the real estate market in Stillwater, Oklahoma, you would not collect data from only one broker’s office. While this office might have access to broader data on the real estate market, as a writer you run the risk of looking biased if you only choose materials from this one source. Collecting information from multiple brokers would demonstrate thorough and unbiased research.

Presenting Visual Information Ethically

Visuals can be useful for communicating data and information efficiently for a reader. They provide data in a concentrated form, often illustrating key facts, statistics, or information from the text of the report. When writers present information visually, however, they have to be careful not to misrepresent or misreport the complete picture.

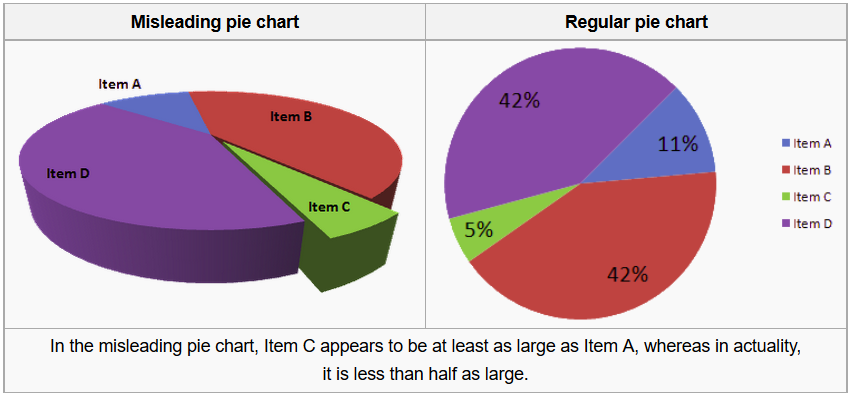

The graphic below shows two perspectives of information in a pie chart. The data in each is identical, but the pie chart on the left presents information in a misleading way (see Figure 17.1). What do you notice, however, about how that information is conveyed to the reader?

Imagine that these pie charts represented donations received by four candidates for city council. The candidate represented by the green slice labeled “Item C” might think that she had received more donations than the candidate represented in the blue, “Item A” slice. In fact, if we look at the same data in a differently oriented chart, we can see that Item C represents less than half of the donations than those for Item A. Thus, a simple change in perspective can change the impact of an image.

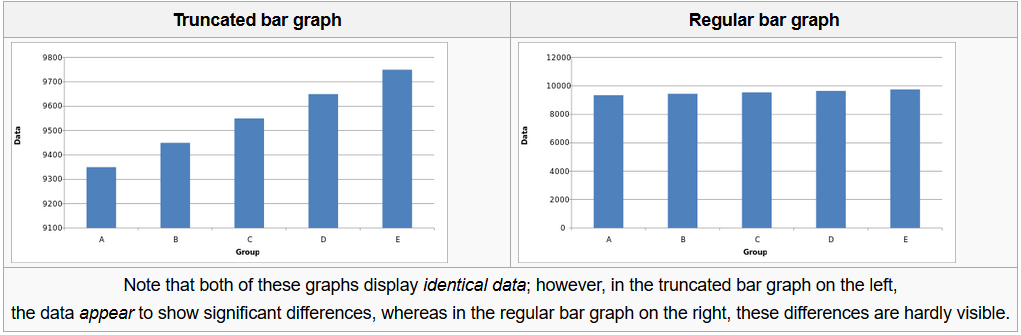

Similarly, take a look at the bar graphs in Figure 17.2 below. What do you notice about their presentation?

If the bar graph above were to stand for sales figures for a company, the representation on the left would look like good news: dramatically increased sales over a five-year period. However, a closer look at the numbers shows that the graph displays only a narrow range of numbers in a limited perspective (9100 to 9800). The bar graph on the right, on the other hand, exhibits the complete picture by presenting numbers from zero to 1200 on the vertical axis, and we see that the sales figures have in fact been relatively stable for the past five years.

Presenting data in graphical form can be especially challenging. Keep in mind the importance of providing appropriate context and perspective as you prepare your graphics. You need to be extra vigilant to avoid misleading your readers with graphics. Graphics will usually be the first thing a reader notices about your document; if a reader finds your images misleading, your entire document may be called into question.

Additional Concerns

You might notice that most of these ethics violations could happen accidentally. Directly lying is unlikely to be accidental, but even in that case, the writer could rationalize and/or persuade themselves that the lie achieved some “greater good” and was therefore necessary. This is a slippery slope.

An even more common ethics violation results from the person who designs the information mistakenly believing that they are presenting evidence objectively—without recognizing their own bias in how they presented that information.

Most ethics violations in technical writing are (probably) unintentional, but they are still ethics violations. That means a technical writer must consciously identify their biases and check to see if a bias has influenced any presentation: whether in charts and graphs, or in discussions of the evidence, or in source use (or, of course, in putting the crucial O-ring information where the launch decision makers would realize it was important).

For example, scholarly research is intended to find evidence that the new researcher’s ideas are valid (and important) or evidence that those ideas are partial, trivial, or simply wrong. In practice, though, most folks are primarily looking for support: “Hey, I have this great new idea that will solve world hunger, cure cancer, and make mascara really waterproof. Now I just need some evidence to prove I am right!” This demonstrates one version of confirmation bias, where people tend to favor evidence that supports their preconceived notions and reject evidence that challenges their ideas or beliefs.

On the other hand, if you can easily find 94 high-quality sources that confirm you are correct, you might want to consider whether your idea is worth developing. Often in technical writing, the underlying principle is already well-documented (maybe even common knowledge for your audience) and the point should be to use that underlying principle to propose a specific application.

Using a large section of your report to prove an already established principle implies that you are saying something new about the principle—which is not true. Authors of technical documents typically do not have the time or space to belabor well-known points or common-sense data because readers do not need to read page upon page of something they already know or something that can be proven in a sentence or two. When you use concepts, ideas, or findings that have been established by others, you only need to briefly summarize your source and provide accurate references. Then you can apply the information from your source(s) to your specific task or proposal.

Ethics and Documenting Sources

The most immediate concern regarding ethics in your technical writing course is documenting your sources. Whatever content you borrow must be clearly documented both in the body of your text and in a Works Cited or References page (the different terms reflect different documentation systems, and not just random preference) at the end.

Including an item only in the source list at the end suggests you have used the source in the report, but if you have not cited this source in the text as well, you could be seen as misleading the reader. Either you are saying it is a source when in fact you did not really use anything from it, or you have simply failed to clarify in the text what are your ideas and what comes from other sources.

Documenting source use in such a way as to either mislead your reader about the source or make identifying the source difficult is also unethical—that would include using just a URL or even an article title without identifying the journal in which it appears (in the Works Cited/References; you would not likely identify the journal name in the report’s body). It would also be unscrupulous to falsify the nature of the source, such as omitting the number of pages in the Works Cited entry to make a brief note seem like a full article.

Dishonest source use includes suppressing information about how you have used a source like not making it clear that graphical information in your report was already a graph in your source, as opposed to a visualization you created based on information within the source.

With the ease of acquiring graphics on the internet, it has become ever more tempting to simply copy and paste images from a search engine. Without providing accurate citation information, the practice of cutting and pasting images is nothing less than plagiarism (or theft); it is unethical and may be illegal if it violates copyright law. Furthermore, it is downright lazy. Develop good habits now and maintain them through practice. Properly cite your images by providing credit to the original creator of the image with full citations. You cannot just slap a URL under a picture, but rather you need to give full credit with an appropriate citation. Any assignment turned in that uses material from an outside source, including graphics and images, needs to include in-text citations as well as a list of references.

What about Open-Source Images?

If you need to use graphics from the internet, a good option is to look for graphics that are open source. Open source refers to material that is freely available for anyone to use. Creative Commons is an organization that has developed guidelines to allow people to “share their knowledge and creativity.” They provide “free, easy-to-use copyright licenses to make a simple and standardized way to give the public permission to share and use” creative work (“What we Do”). There are a number of options that a creator has in regard to how they want to set up permissions, but the idea is that these works are free for anyone to use; they are open source.

Graphics created by the federal government, say from the National Park Service or the FDA or the EPA, are not under copyright and therefore can be used without having to go through the sometimes-onerous process of securing permissions. This is particularly helpful for written materials that will be professionally published.

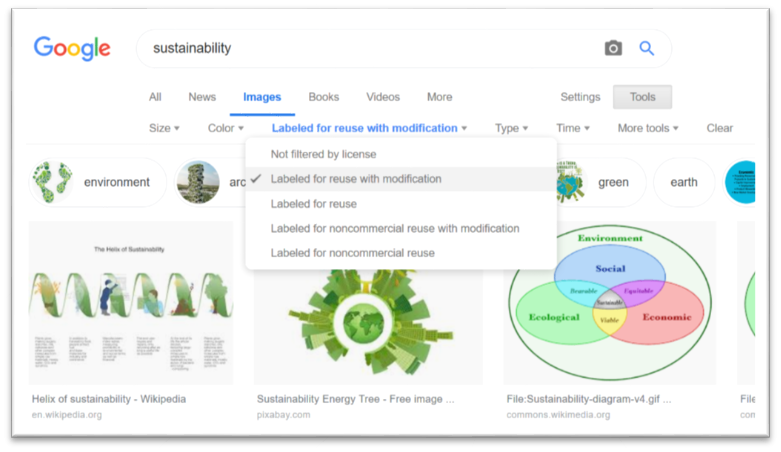

Likewise, you can customize a Google image search so that only images that are open source will come up. If you click on the “Tools” button, you have the option of filtering results by how they are licensed. See Figure 17.3.

Regardless of the copyright, you should always keep track of where you found the graphics, and for assignments for your class, you need to record the source so you can cite it. If you use images (or anything at all) in an assignment that you did not create, you need to indicate as much. Just because a picture or data visualization is open source does not mean that you can pass it off as your own work. And if you don’t cite it, plagiarism is exactly what you are doing—whether or not that was your intention.

Many problems in documenting sources occur because the writer is missing the point of source use. Remember, you must clearly distinguish between your ideas and borrowed material, and you must use borrowed material primarily as evidence for your own directly stated ideas.

Intellectual Property

Patents and trademarks are company names (Walmart), logos (the Target bullseye), processes or slogans (McDonalds “I’m lovin’ it”) that belong to a person or company. None of these things can be used without proper recognition of or approval from the appropriate company or individual involved. A company uses a ™ to show something is trademarked or an ® for something registered with the U.S Patent and Trademark Office. An example would be Nike and their famous swoosh symbol.

This law extends beyond the major companies. Any written document in your own company is copyrighted by law once produced. That means if you are borrowing a good idea from a friend at another company, you must cite them as a source. Also, although not required by law, it is a good idea to cite sources from inside your own company as well. You would not want someone else taking credit for your ideas. Why should you treat others any differently?

The legal consequences are most notable when one considers writing in the professional world. While plagiarizing in the classroom may give you a failing grade, plagiarizing in the workplace can get you fired and could result in a costly lawsuit or possibly even jail time. It is not only ethical to follow these rules, it is an enforced law. Make sure you properly document all sources so as not to mislead a reader.

Copyright law includes items whose distribution is protected by law (books, movies, or software). The copyright symbol is shown with a ©. Copyright is different from plagiarism in that it is a legal issue. Only the copyright holder, the person/organization who owns the protected item, can copy it. Spend a few minutes checking out The United States Patent and Trademark Office for clarification on trademarks, patents, and copyright.

When determining if a copyright law has been violated, the court makes certain considerations:

- The character, purpose of use, and amount of information being used. Was it a phrase, sentence, chapter, or an entire piece of work? Was the information simply copied and pasted as a whole or changed? Was it taken from something published or unpublished? What was it used for?

- If the person using another’s material did so to profit from it. Only the copyright holders should profit from material they own. For example, a faculty member cannot use their personal DVD for a movie screening on campus and charge students to attend the viewing.

- If using someone else’s property affected the market for the copyrighted work. For example, if you take an item that would cost money to buy and copy it for other people, you are affecting the market for that product since the people you give it to will now not have to purchase it themselves. Therefore, the original owner of the material is denied a profit due to your actions.

When dealing with copyright questions, consider the following tips:

- First, find out if the item can be used. Sometimes, the copyright holder allows it if credit is given.

- Second, do not use large amounts of another person’s information.

- Third, if possible, ask permission to use another person’s work.

- Finally, and most importantly, cite sources accurately so as to give credit to another person’s ideas if you are able to use them.

Ethics, Plagiarism, and Reliable Sources

Unlike personal or academic writing, technical and professional writing can be used to evaluate your job performance and can have implications that a writer may or may not have considered. Whether you are writing for colleagues within your workplace or outside vendors or customers, you will want to build a solid, well-earned, favorable reputation for yourself with your writing. Your goal is to maintain and enhance your credibility, and that of your organization, at all times.

Credibility can be established through many means: using appropriate professional language, citing highly respected sources, providing reliable evidence, and using sound logic. Make sure as you start your research that you always question the credibility of the information you find. You should ask yourself the following questions:

- Are the sources popular or scholarly?

- Are they peer reviewed by experts in the field?

- Can the information be verified by other sources?

- Are the methods and arguments based on solid reasoning and sound evidence?

- Is the author identifiable, and do they have appropriate credentials?

Be cautious about using sources that are not reviewed by peers or an editor, or in which the information cannot be verified or seems misleading, biased, or even false. Be a wise information consumer in your own reading and research in order to build your reputation as an honest, ethical writer.

Quoting the work of others in your writing is fine—provided that you credit the source fully enough that your readers can find it on their own. If you fail to take careful notes, or the words/ideas are present in your writing without accurate attribution, it can have a negative impact on you and your organization. When you find an element you would like to incorporate in your document, the same moment as you copy and paste or make a note of it in your research file, note the source in a complete enough form to find it again.

Giving credit where credit is due will build your credibility and enhance your document. Moreover, when your writing is authentically yours, your audience will catch your enthusiasm, and you will feel more confident in the material you produce. Just as you have a responsibility in business to be honest in selling your product or service and avoid cheating your customers, so you have a responsibility in business writing to be honest in presenting your idea, and the ideas of others, and to avoid deceiving your readers with plagiarized material.

Ethical Writing

Throughout your career, you will be required to create many documents. Some may be simple and straightforward and some may be difficult and involve questionable objectives. Overall, there are a few basic points to adhere to whenever you are writing a professional document: do not mislead; do not manipulate; do not stereotype.

Do Not Mislead

This has more than one meaning to the professional writer. The main point is clear. When writing persuasively, do not write something that can cause the reader to believe something that is not true. This can be done by lying, misrepresenting facts, or just “twisting” numbers to favor your opinion and objectives. Once you are on the job, you cannot leave out numbers that show you are behind or over-budget on a project no matter how well it may work once it is completed. Be cautious when using figures, charts, and tables by making sure they visually represent quantities with accuracy and honesty. While this may seem easy, when the pressure is on and there are deadlines to meet, taking shortcuts and stretching the truth become ever more tempting.

Do Not Manipulate

Do not persuade people to do what is not in their best interest. A good writer with bad motives can twist words to make something sound like it is beneficial to all parties. The audience may find out too late that what you wrote only benefited you and actually hurt them. Make sure all stakeholders are considered and cared for when writing a persuasive document. It is easy to get caught up in the facts and forget all the people involved. Their feelings and livelihood must be considered with every appropriate document you create.

Do Not Stereotype

Most stereotyping takes place subconsciously now since workplaces are careful to not openly discriminate. It is something we may not even be aware we are doing, so it is always a good idea to have a peer or coworker proofread your documents to make sure you have not included anything that may point to discriminatory assumptions.

The not-for-profit organization Project Implicit has been researching subconscious biases for years and has developed several, free online tests. The tests can help you unearth and understand your own proclivities and prejudices. Knowing your biases may help you begin to overcome them.

Attributions

“Ethics and Documenting Sources” by Michael Beilfuss is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Feedback/Errata