9

Long Term Care & Populations with Special Needs

Patricia Driscoll, JD

Texas Woman’s University

Anastasia Miller, PhD

University of Louisville

“The longer I’m alive the more beautiful I realize life is.” – Unknown

Learning Objectives

•Describe the main characteristics of LTC

•Characterize the client populations needing long term care and the projected growth

•Explore the continuum of LTC

•Identify the community and institutional components of LTC

•Identify and discuss financial and regulatory issues in LTC

•Identify and describe staffing needs, roles, and responsibilities in long term care

•Identify, examine, and discuss issues, trends and ethical concerns in LTC

•Examine the unique healthcare needs of populations with special needs

Introduction

The current growth of the U.S. population ages 65 and older, driven by the large baby boom generation—those born between 1946 and 1964—is unprecedented in U.S. history. This demographic transition presents challenges to the delivery of healthcare and changes to the health needs of this population. According to the US Census Bureau, the US population aged 65+ years is expected to reach 83.7 million by 2050. This Chapter focuses on critical key issues in the organization and provision of long term care (LTC):

Introduction to Long Term Care

Long term care (LTC) is a continuum of services, both medical and social, that are designed to support individuals whose capacity for self-care is limited because of a chronic illness; injury; physical, cognitive, or mental disability; or other health-related conditions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). Historically, the term “long term care” has been associated with services and supports delivered in institutions to help frail older adults and younger persons with disabilities maintain their daily lives. Recently, alternative terms have emerged to denote a broader focus. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended) uses the term “long-term services and supports” (LTSS) and defines the term to include institutional and community-based services. This broad range of personal, social, and medical services are provided in a multitude of locations, including private homes, adult day-care settings, residential care/assisted living facilities, and nursing homes.

This chapter provides an overview of LTC, its primary users, types of institutional and community-based services, venues for service provision, as well as financing of these services. Emerging issues related to disparities, special populations and the digital revolution affect the delivery of LTC services and will also be discussed.

Consumers of LTC

Although people of all ages may need long term care services, the use of these services is highly correlated with age. Therefore, it is not surprising that three age related factors are driving current utilization of LTC: population shifts, increasing life expectancies with attendant chronic conditions, and the increased risk of injuries and disabilities that these create.

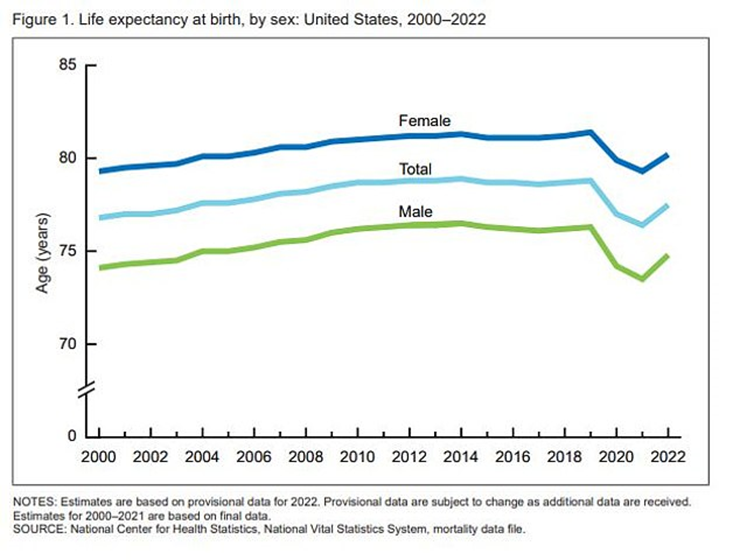

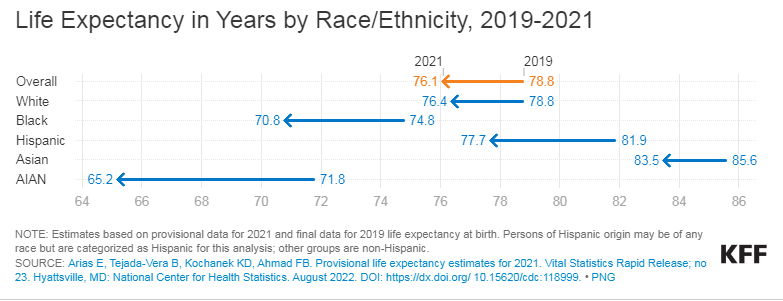

The number of Americans over age 65 is projected to shift from 47.8 million in 2015 to over 87.9 million in 2050, representing an increase of 84% and comprising 22% of the population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). This population is also living longer. Although there was a decline of 2.4 years between 2019 and 2021 driven largely by the COVID-19 pandemic, (CDC, 2022) overall life expectancy at age 65 increased from 11.9 years in 1900 to 19.1 years in 2010 and almost doubled from 5.3 years to 9.1 years at age 80 (He et al., 2016). Conversely, the US birthrate fell by 4% hitting an all-time low. The resulting population shift is an aging population with fewer caregivers.

Data Source: National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS – Death rates and life expectancy at birth. Date accessed [May 9, 2022]. Available from https://data.cdc.gov/d/w9j2-ggv5

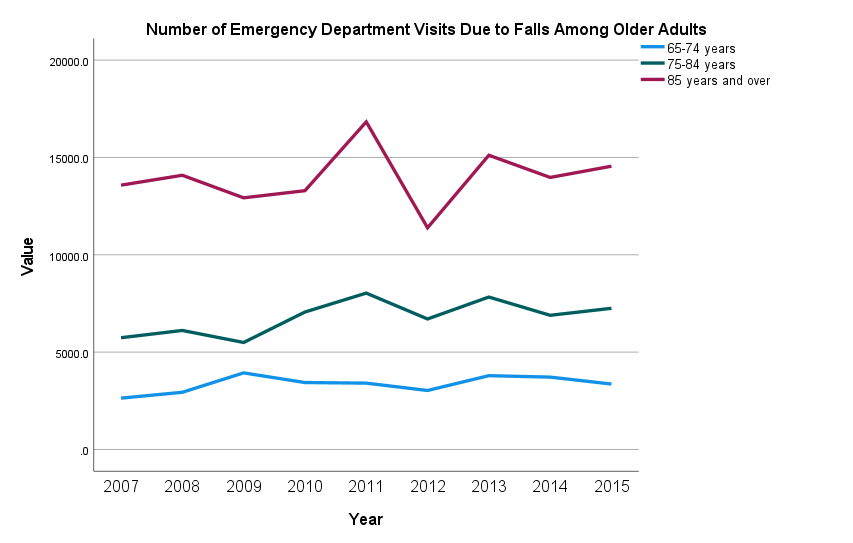

As people age, they are also at greater risk of injuries and disabilities that may make care necessary. According to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, (2018), there were 2,216,681 emergency room visits among adults aged ≥65 years due to falls. Older Americans are significantly more likely to have a disability. Some 46% of Americans ages 75 and older and 24% of those ages 65 to 74 report having a disability, according to estimates from the Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey (ACS). Of the 14 million adults who needed LTC in 2018, 56% were 65 and older (Hado & Konisar, 2019). Almost 70% of adults aged 65 years and older will require long-term care at some point (Administration for Community Living, 2020).

Data Source: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (CDC/NCHS) Date accessed [May 9, 2022]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020/hp2020-errata-page.htm

Children may need LTC due to developmental or intellectual disabilities. Although approximately 14% of children between 3 and 18 are disabled, their comparative utilization of institutional LTC is less than 1%. Adults between 18 and 64 constitute approximately 39% of the use of LTC (Oppenheimer, 2021) due primarily to neurodegenerative diseases.

Continuum of Care

Long-term services and supports (LTSS) encompass a variety of health, health-related, and social services that assist individuals with functional limitations. LTSS includes assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) such as eating, bathing, and dressing and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as housekeeping and money management over an extended period.

The goal of LTSS is to facilitate functioning among people with disabilities. Most LTSS is delivered by unpaid family or friends, many of whom struggle to balance their care activities with employment and other family responsibilities (Spillman et al. 2014). This is typically referred to as “informal” (unpaid) care. However, paid LTSS provided by paraprofessionals is becoming increasingly important as the availability of family caregivers shrinks. Coming generations of older adults will have fewer children to provide care, and more women in their 50s and 60s, who provide much of the care received by older adults, work outside the home. LTSS are delivered in a variety of settings, some institutional (e.g., nursing homes), and some home and community-based (e.g., adult day services, assisted living facilities, and personal care services) (Thach and Wiener 2018). More than one-half of older adults are projected to experience serious LTSS needs (requiring help with two or more ADLs or having severe cognitive impairments) and use paid LTSS after turning 65. More than one-third (39%) will receive nursing home care (Johnson et. al., 2021).

Home- and Community-Based Services

Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) are types of person-centered care delivered in the home and community. Home- and community-based services (HCBS) allow people with significant physical and cognitive limitations to live in their home or a home-like setting and remain integrated with the community. Services include skilled care, personal care (dressing, bathing, toileting, eating, transferring to or from a bed or chair, etc.), home delivered meals, transportation and access, supported employment, home repairs and modifications, home safety assessments, and information and referral services (CMS, 2021).

The terms home health and home care are often confused. Although both types of care are delivered in the home, there are important differences between home care and home health care. Home health is the provision of medical services delivered by skilled providers in the home. This type of care is often paid for by Medicare, Medicaid and private payers. Home care, on the other hand, is personal care, companion care, custodial care or homemaker services and usually paid for out-of-pocket. However, The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has given new flexibilities to Medicare Advantage (MA) plans to provide supplemental benefits that address long-term services and supports (LTSS) needs and social determinants of health (SDOH) among their members. In 2019, CMS expanded its definition of “primarily health-related” benefits to include additional items or services that are LTSS-type services, such as adult day health, in-home personal care attendants, and support for beneficiaries’ family caregivers (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), 2022).

Home Health Care

Home health care is a formal, regulated program of care delivered in the home, and can include a range of services provided by skilled medical professionals, including skilled nursing care, physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy. Home health care can also include skilled, non-medical care, such as medical social services or assistance with daily living from a highly qualified home health aide.

Roughly one out of every four home health patients is over the age of 85, while just 10.9% of the overall Medicare population is over that age, according to the Alliance for Home Health Quality Innovation (2020). At the same time, nearly half of all home health users suffer from five or more chronic conditions, such as asthma, arthritis, diabetes or heart disease. Just 22.4% of all Medicare beneficiaries suffer from that many chronic conditions all at once. Home health users are additionally more likely to live alone and have two or more functional limitations. These and other statistics reflect the high-acuity profile of most home health patients. Also, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and hospitals discharging individuals back home more quickly to preserve capacity, that profile is only growing more acute.

To be eligible for the home health benefit under Medicare, the patient must be under a doctor’s care, with a plan of care that the doctor regularly reviews, the recipient must be homebound and unable to leave the home unaided without the possibility of risk. Sources for home health care funding include Medicare, Medicaid, the Older Americans Act, the Veterans Administration, and private insurance.

Adult Day Care

Adult day care (ADC) is a group program designed to meet the needs of functionally and/or cognitively impaired adults and provide respite for family caregivers. Adult daycare centers offer a wide array of services that range from basic health services, meals and activities to intensive health services for those who might otherwise have to be in a skilled nursing center. In general, there are three main types of adult day care centers: those that focus primarily on social interaction, those that provide medical care, and those dedicated to Alzheimer’s care.

Adult day care services are a growing source of long-term care. The National Adult Day Services Association estimates that there are currently 7,500 ADCs across the United States. Half of ADCs serve racial and ethnic minorities (Lenon et. al., 2021), and the population that utilizes these services tends to be more ethnically diverse than those found in institutional settings (Harris-Kojetin et. al., 2019). Nearly 78% of adult day centers are operated on a nonprofit or public basis, while the other 22% are for-profit. Seventy percent of adult day centers are affiliated with larger organizations such as home care, skilled nursing facilities, medical centers, or multi-purpose senior organizations. Daily fees for adult day services vary by services provided. The national average rate for adult day centers is $61 per day (for an average of 8-10 hours of care) (Aging in Place, 2022).

Medicare does not cover adult day care. Medicaid will pay something in nearly every state, though the amount is often limited. Long term care insurance may cover adult day programs, and some financial assistance may be available through a federal or state program like the Older Americans Act or Veterans Health Administration.

Home Delivered and Congregant Meals

The Elderly Nutrition Program (ENP) was designed specifically to address problems of inadequate dietary intake and social isolation among the elderly. ENP is authorized by and receives funding under the Older Americans Act Nutrition Program. Additional funding is provided through Title XX block grants, Medicaid waivers and private donations. Services include both home-delivered meals (commonly referred to as Meals on Wheels) and healthy meals served in group settings, such as senior centers and faith-based locations. In addition, the programs provide a range of services including nutrition screening, assessment, education, and counseling. Nutrition services also provide an important link to other supportive in-home and community-based supports such as homemaker and home-health aide services, transportation, physical activity and chronic disease self-management programs, home repair and modification, and falls prevention programs.

Knowledge Check What are the patient services most offered by Home Health Care, Hospice Care, and Adult Day Care?

Institutional Care

Retirement Communities

Retirement Community and independent living are often used interchangeably. Independent living is simply any housing arrangement designed exclusively for older adults, generally those aged 55 and over. Housing varies widely, from apartment-style living to single-family detached homes. In general, the housing is friendlier to aging adults, often being more compact, with easier navigation and no maintenance or yard work.

While residents live independently, most communities offer amenities, activities, and services. Activities can include arts and crafts, continuing education classes, or movie nights. Services provided may range from daily meals, basic housekeeping and laundry services to monitoring and/or assistance with medications. Since independent living facilities are aimed at older adults who need little or no assistance with activities of daily living, most do not offer medical care or nursing staff (Help Guide, 2020).

Assisted Living

Assisted living facilities (ALFs) are designed for older people who are no longer able to manage living independently and need help with daily activities such as bathing or dressing, but don’t require the round-the-clock nursing care. ALFs provide some nursing care and rehabilitation services in addition to personal care and 24-hour supervision. Assisted living facilities usually provide residents with their own apartments or rooms, as well as some common areas.

Nationally, 52% of the residents in ALFs are age 85 years and older; have arthritis or heart disease, and 42% have dementia or moderate/severe cogitative impairment. A majority require help with activities of daily living (ADL), most commonly taking medications (87%), bathing (64%), walking (57%), and dressing (48%) (Harris-Kojetin, et. al., 2019). In addition, the mental health care needs of ALF residents are significant and rising; 31% are diagnosed with depression and more than 11% have serious mental illness (Hua et. al., 2021). Despite the acuity of residents, few ALFs have a registered nurse on staff.

ALFs operate predominantly on a private pay basis. All states require ALFs to be licensed, however, regulations vary from state to state and enforcement is not uniform. Therefore, quality is also variable.

Skilled Nursing Facilities

Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are licensed healthcare residences for individuals who require a level of medical care that must be provided by or under the direct supervision of licensed health professionals, such as registered nurses (RNs) and physical, speech, and occupational therapists. Care in SNFs includes both long-term residential care and short-term post-hospital or rehabilitative care. Rehabilitation is as a key component for short-term stays and these are funded primarily through Medicare or commercial insurers. Medicare does not pay for long-term or permanent stays in nursing homes. Medicaid, on the other hand, covers both short-term stays and extended stays in SNFs for seniors with limited assets and low income who have a medical need for this high level of care. This coverage and the eligibility requirements vary by state. SNFs may provide only long term care, only short-term care for rehabilitation purposes or both. In order to be certified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), SNFs must meet strict criteria and are subject to periodic inspections to ensure that quality standards are being met.

SNF residents, whether short- or long-term, tend to be old, female, and need extensive help with ADLs. Cognitive impairment is also widespread in this population. with between 53% and 67% exhibiting severe impairment ( Donnelly et al., 2020). A relatively small number of individuals under the age of 65 also receive care in SNFs. This population often has different comorbidities and needs (i.e., traumatic brain injury, psychiatric illness, and substance use disorders).

The number of Americans living in SNFs for extended periods has been falling over the past decade as more seniors choose to remain in their homes. The trend was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic and it is expected that demand for senior care facilities will fall as seniors exercise their preference to age in place and utilize community and home-based services.

Continuing Care Retirement Communities

Continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs), also called life care communities, integrate different levels of service in one location. Many of them offer independent housing (houses or apartments), assisted living, and skilled nursing care and memory care all on one campus. Residents can move from one area to another based on the level of service needed and stay within the CCRC. For example, residents who can no longer live independently move to the assisted living facility or sometimes receive home care in their independent living unit. If necessary, they can enter the CCRC’s nursing home or memory care unit. A CCRC is a good option for seniors who want to age in place but might not have the support system to do so.

CCRCs are paid for through private financing unless services are received in a Medicare certified skilled nursing facility. CCRCs require a substantial entrance fee, which can range from the low six-figures to upwards of a million dollars. In addition to this entrance fee (which can be nonrefundable should the resident move out or pass away), residents are required to pay a monthly fee based on amenities and the type of contract. If a community isn’t financially stable, there is a risk of losing the entire investment that could leave ageing residents financially and medically exposed at the end of their lives.

Knowledge Check Who uses long term care services and why do they use them?

Issues in Long Term Care

Financing And Reimbursement

The United States lacks a comprehensive approach to financing LTC. The most common source of care for people living in the community who need assistance for functional or cognitive impairment is unpaid assistance from family and friends. Medicaid and Medicare are the chief public programs responsible for financing long term care. The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Social Services Block Services Block Grant program also provide some funding. Commercial insurance, private long term care insurance and out-of-pocket spending accounts for the remainder of funding. It is estimated that spending on LTC services exceeds $420 billion per year (Werner & Konetzka, 2022).

Medicare funds LTC only temporarily and indirectly, by covering nursing home and home-based care for skilled needs, often after a hospital discharge, but not for ongoing help with activities of daily living. However, as mentioned previously, Medicare Advantage plans have begun to include some community and home based long term care services as part of their offerings. Medicaid finances more than half of all LTC for those who need help with daily activities, such as help with bathing, dressing, or eating. However, Medicaid is only available to people who qualify and spend down their own assets. Medicaid eligibility and coverage varies widely by state.

None of the public sources of LTSS financing are designed to cover the full range of services and supports that may be needed by individuals with long term care needs. LTC insurance differs from regular health insurance and is available to cover some LTC services. However, coverage varies, and premiums are expensive, particularly if the coverage is not purchased by age 55. Five percent of applicants between ages 60 and 69 are denied long term care insurance coverage and many companies won’t offer coverage after age 75. Therefore, it is not surprising that only 7.5 million Americans have some form of long term care insurance as of January 1, 2020 (American Association for Long Term Care Insurance, 2021).

Health-policy experts have recognized that the cost and financing of LTC as a serious concern. Expensive institutional care still predominates when consumers prefer home – half of the states still spend twice as much on institutional care in comparison to community care (Werner & Konetzka, 2022). Given our aging population and the pervasiveness of smaller, more geographically dispersed families, LTC is only going to become an even greater challenge.

Knowledge Check What Long term care services are covered by Medicare? What restrictions are placed on coverage?

Regulatory Compliance

Both the federal and state governments regulate long term care services and facilities. The standards are set by agencies that pay for services, monitor quality of care, and establish rules for licensing staff. Major goals of long term care regulation have been described as (1) consumer protection, specifically, ensuring safety, quality of the care received, and legal rights of consumers, and (2) accountability for public funds used for care (IOM, 2001).

Home and community-based services are regulated by three formal oversight mechanisms – oversight by government (federal, state and local), a consumer advocacy program, and accreditation. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) establish minimum quality standards and ensure that sufficient services are being provided. States oversee the licensing of organizations and professional staff. The Ombudsman program (consumer advocacy) is administered by the Administration on Aging (AoA)/Administration for Community Living (ACL). Ombudsmen can address complaints and advocate for improvements in the long term care system. Accreditation is a voluntary program that indicates that the organization has met certain standards or qualifications. The Joint Commission is the primary accreditor of LTC facilities.

Regulation has been the primary approach to improving the quality of care and quality of life in of LTC facilities. The Nursing Home Reform Act was passed as part of the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA ’87) (Hawes, 1996). The performance standards established by OBRA ’87 focused on quality of care, resident assessment, residents’ rights, and quality of life. The Affordable Care Act included provisions to increase nursing home transparency and accountability, target enforcement, and prevent abuse and other crimes against residents.

Resultant regulations are extensive and in fact nursing homes have been called the most regulated entities in America. The sanctions for failing to comply can be severe, ranging from fines to probation to closure. States are largely responsible for actual oversight and enforcement through inspections, surveys and response to complaints.

In spite of the heavy regulation, it can be difficult for nursing home residents and their families to assess the quality of a nursing home. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) produces the Nursing Home Compare website, which enables users to explore data related to health and safety, quality of care, staffing, and other topics (McGarry & Grabowski, 2017). However, the tool has been criticized for flawed content and has not been widely used (Grabowski, 2020).

Staffing Challenges

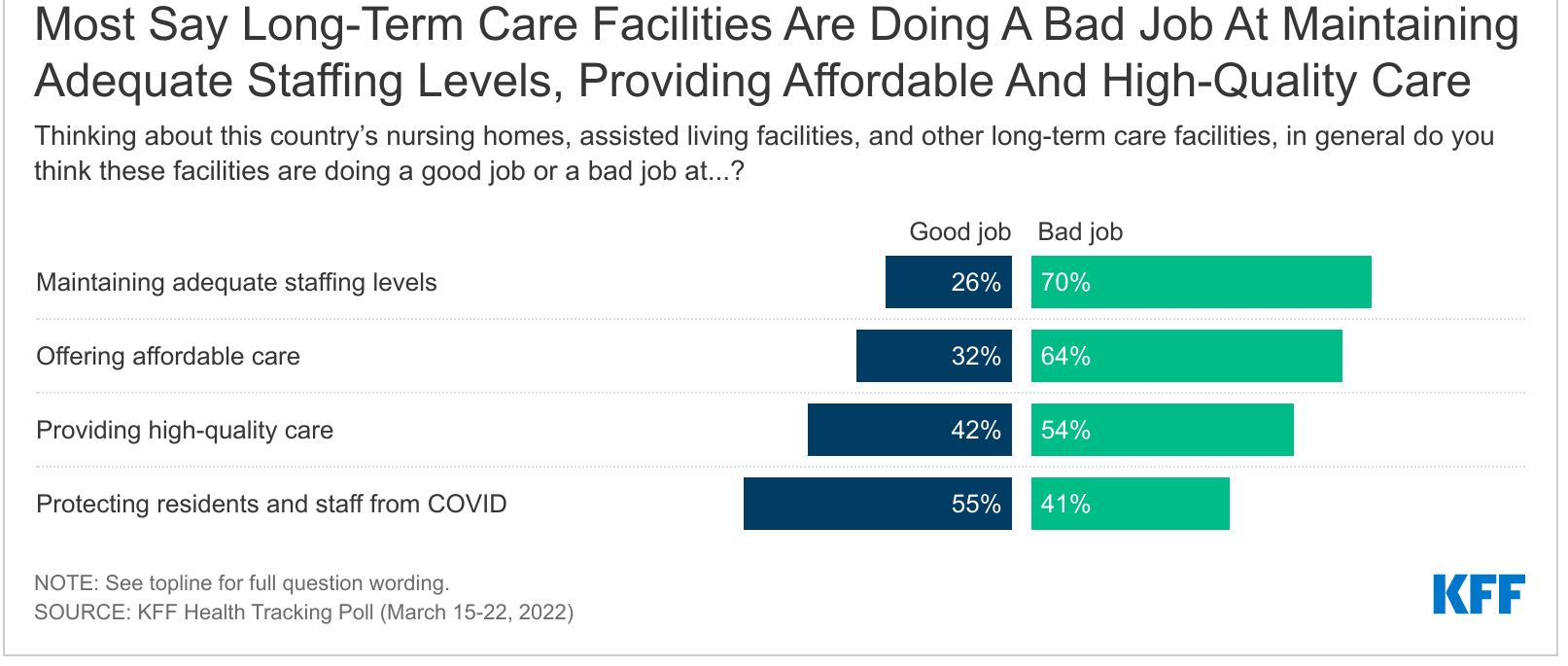

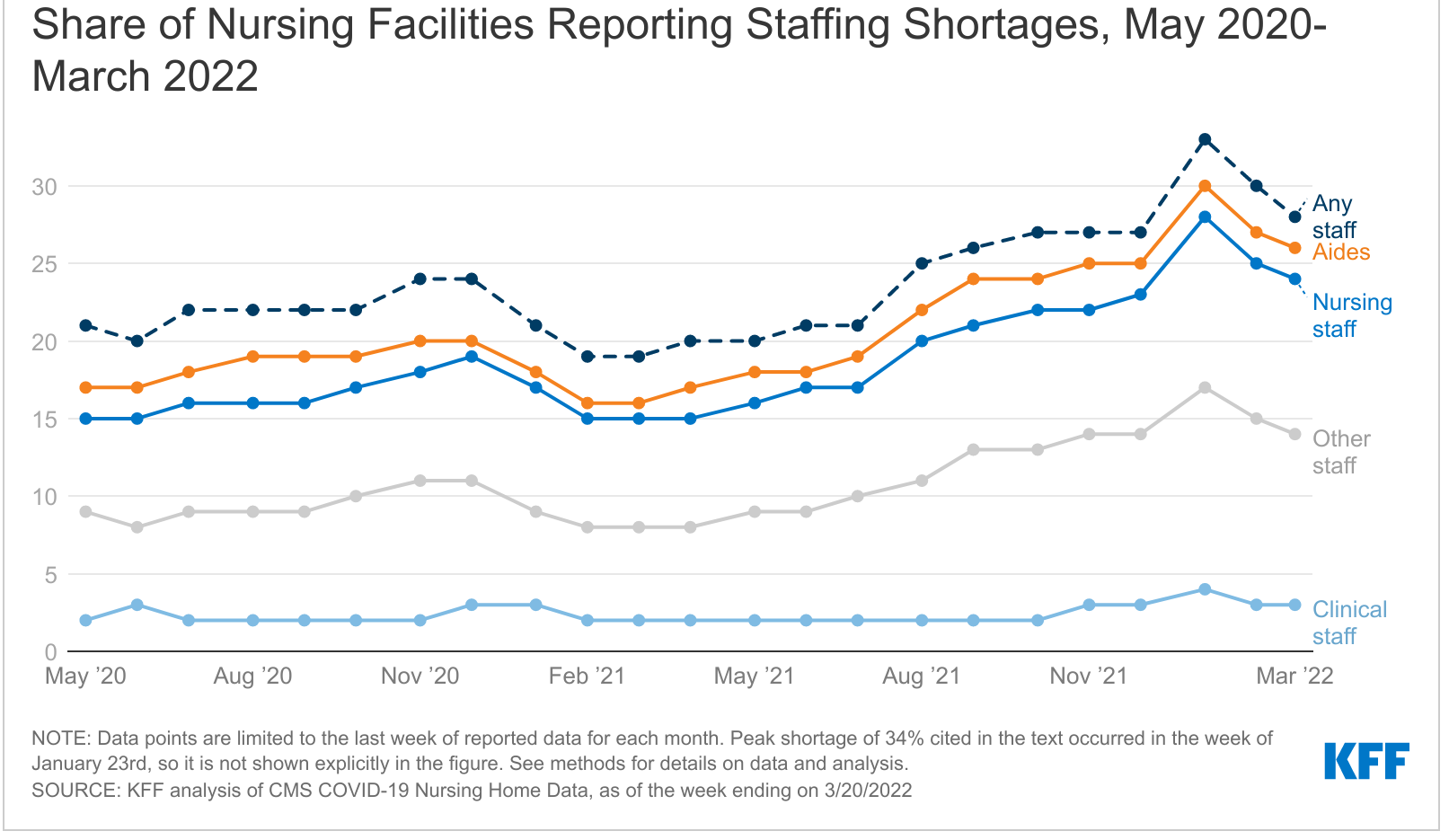

Workforce issues in LTC include growth in demand and competition for staff, aging of the workforce, and staff shortages. Workforce issues are critical for LTC as staffing is one of the most important determinants of the adequacy and quality, as well as availability of care.

Employment in healthcare occupations is projected to grow 16% from 2020 to 2030, much faster than the average for all occupations. The largest growth areas are projected to be Nurse practitioners (52.2 %), Occupational therapy assistants (36.1 %), Physical therapy assistants (35.4 %), and home health and personal care aids (32.6 %) (BLS, 2021). Despite the dramatic job growth, this will not be sufficient to meet future needs since growth in demand is expected to expand faster. Regardless of actual growth, it can be anticipated that there will be a dramatic shortage of all healthcare workers which will force LTC to compete with other segments of the healthcare system.

In concert with the overall aging of the US population, the LTC workforce is aging. A 2020 Nursing Workforce Study reported that the average age of RNs was 51 years, up from 43.5 years in 2019. Additionally, more than one-fifth of all nurses reported they plan to retire from nursing over the next 5 years (Smiley, et al.). This will further challenge staffing for LTC.

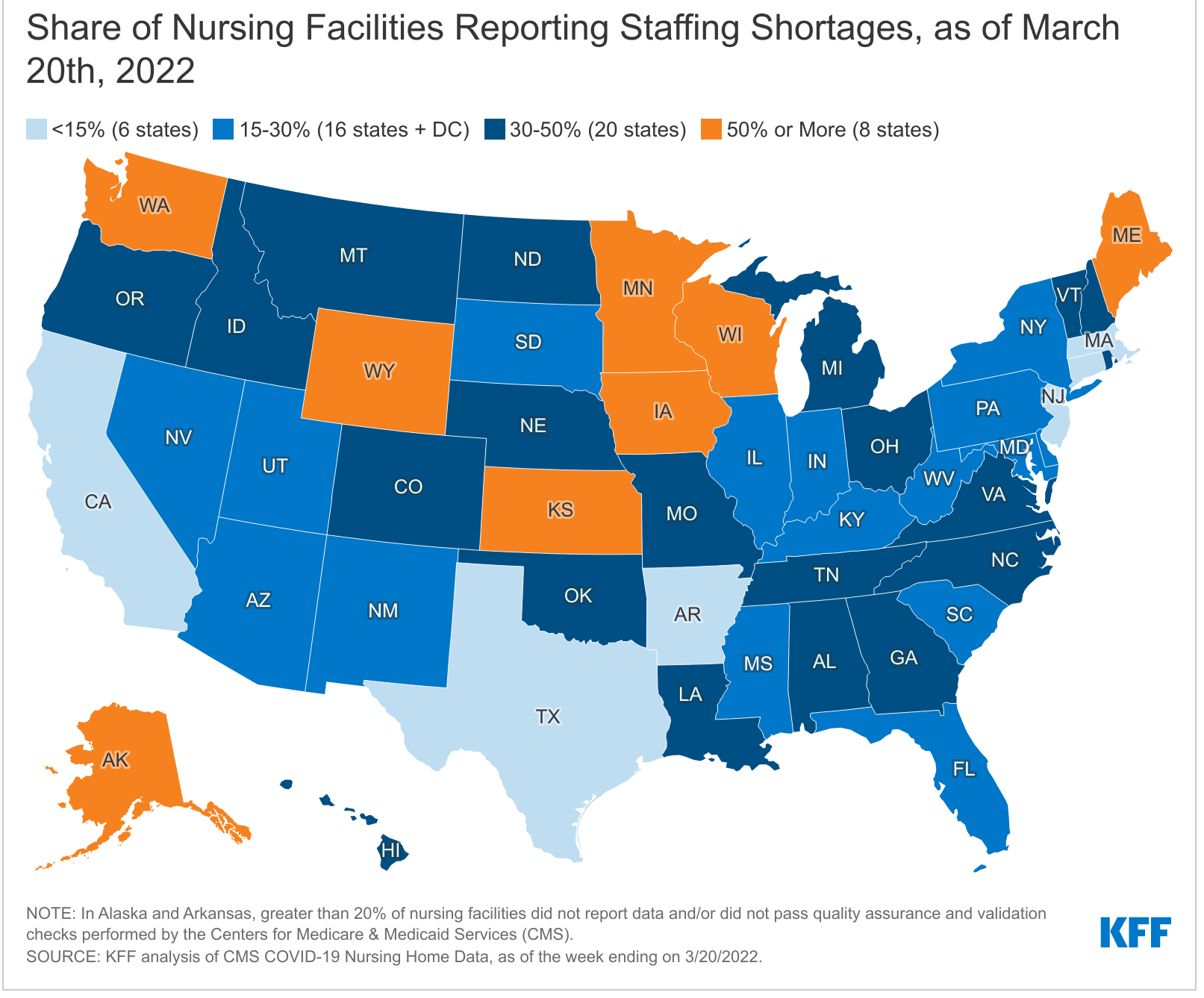

Staff shortages in LTC were a problem before the coronavirus pandemic. But the departure of 420,000 employees over the past two years has exacerbated the issue at the same time that acute care hospitals were experiencing increased demand for services and staff shortages of their own. Fifty-nine percent of nursing homes and 30% of assisted living communities characterize their staffing situation as “severe.” (AHCA/NCAL, 2021). There have always been struggles to fill positions in LTC facilities, but nursing homes alone have seen the employment level drop by 14% or 221,000 jobs since the beginning of the pandemic.

Obstacles to hiring in LTC have been identified as lack of qualified or interested candidates, limited training and career advancement opportunities, difficulty of the work, and poor pay and benefits. Innovative efforts will be required to reverse the trend, including viewing staff as customers, sponsoring education, focusing on increasing diversity, as well as expanding the use of volunteers and reimagining traditional roles.

Palliative and End of Life Care

While the objective of both hospice and palliative care is pain and symptom relief, the prognosis and goals of care tend to be different. Hospice is comfort care without curative intent; the patient no longer has curative options or has chosen not to pursue treatment because the side effects outweigh the benefits. Palliative care is comfort care with or without curative intent.

Hospice care is similar to palliative care, but there are differences. Because more than 90% of hospice care is paid for through Medicare, hospice patients must meet Medicare’s eligibility requirements; palliative care patients do not have to meet the same requirements. To qualify for care from a Medicare- certified hospice, the attending physician and the hospice physician must certify that the patient is terminally ill, with a medical prognosis of 6 months or less to live. The patient must also sign an election statement to elect the hospice benefit and waive all rights to Medicare payments for the terminal illness and related conditions. Most hospice care is provided at home — with a family member typically serving as the primary caregiver. However, hospice care is also available at hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities and dedicated hospice facilities. Hospice care includes a broad array of services to reduce pain, and address physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs. To help families, hospice care also provides counseling, respite care and practical support.

Medicare, Medicaid and most private health insurers provide palliative care services for patients who are hospitalized. However, they tend not to cover services delivered by registered nurses, social workers and chaplains, coordination of care, social and spiritual counseling, or advanced care planning and family support to patients with debilitating conditions at home. Managed care plans, under which providers are paid a lump sum each month to cover the care of each patient, are more likely to cover palliative services.

For older US adults at the end of life, 70% express a preference to die at home whereas 30% actually do (Hamel, Wu & Mollyann, 2017). This discordance could be attributable in part to the variable access to and funding of home and end-of-life care. Nevertheless, there will be a growing need for home and community-based services to support the wishes of this population with activities of daily living and staying independent toward the end of life (Iyer & Brown, 2022).

Care Transition

Care Transition is a process of transferring a patient’s care from one setting or level of care to another, such as from hospital to home or SNF; between institutional and HCBS settings; or SNF to hospital or home. These transitions are particularly vulnerable points in the continuum of care of any patient. Care transitions between settings are a well-known cause of medical errors. Transitions involving LTC are particularly challenging because of a high prevalence of cognitive impairment, unclear decision-making status, distant families, and unclear or conflicting documentation.

The risks of transfer for LTC patients are highest for those without documented advance directives and those with chronic health conditions, mental health conditions, and limited functional abilities. Care transitions can be disruptive, distressing, and potentially harmful for elderly, particularly when continuity of care is impacted by ineffective communication, medication errors, and lack of awareness of advance directives.

A major challenge in ensuring continuity of care across health care settings is the effective communication of information between care providers and institutions. This includes advising care providers of the patient’s medications upon transfer to the new institution or service, as well as reconciling the patient’s medications upon discharge, ensuring that providers have access to complete care plans, and providing adequate patient /family education.

Residents in long term care (LTC) are at risk for frequent hospitalizations, functional decline, and death. Transitions from the hospital, with declines in functional status, and new life-threatening diagnoses, are common in LTC. These transitional events are opportunities to review resident/family understanding and update goals of care. This is also an opportunity to have conversations about advance care planning.

The key component of successful transition is information exchange, especially in long term care (LTC). Unfortunately, LTC is behind other care settings in adoption of health information technologies (HIT) which facilitates information sharing across settings. However, well-defined protocols can promote coordinated care and safe transitions.

Effects and Aftermath of Covid

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an enormous impact on the long term care delivery system. It affected all aspects of LTC and exposed the cracks in our system of providing and funding long term care. It also brought to the forefront complex ethical issues about healthcare equity that impact the aging and disabled population (Werner, Hoffman & Coe, 2020).

According to OECD (2021), the LTC sector was generally ill-prepared to tackle a health emergency and LTC accounted for 40% of total COVID-19 deaths. Demand for long term care in institutional settings declined sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Miller, 2021). It is expected that Americans’ demand for LTC facilities will continue to fall post pandemic, underlining the need for more support for elders to remain at home.

The pandemic had a devastating effect on those living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Increased social isolation due to visitation restrictions had an adverse impact on the physical and mental wellbeing of residents leading to feelings of abandonment and isolation. In addition, family caregivers experienced significantly increased levels of stress. Despite these challenges, LTC facilities used video conferencing platforms, outdoor visits, and even window events and get-togethers to maintain connectivity and contact with loved ones (Allen, 2021).

As demand for institutional has decreased, a variety of pandemic-related factors have created an opportunity to rethink care at home. An HHS study found a 63-fold increase in Medicare telehealth utilization during the pandemic (US Department of Health & Human Services, 2021). The pandemic also accelerated the use of remote patient monitoring. For example, the Mayo Clinic used remote patient monitoring to effectively manage COVID-19 patients at home (Mayo, 2022). Telemedicine, remote monitoring other digital tools hold great promise for helping seniors access health care from where they want it — at home.

The American Rescue Act, which was proposed by the Biden Administration and passed by Congress in early 2021, increased the federal share of states’ Medicare spending on home and community-based services, it is hoped that this will support an expansion of rehabilitative services outside of institutions further responding to evolving consumer needs (Miller, 2021).

Trends in LTC

Digital Transformation

Technology to help keep seniors safe has been in use for a long time, things such as life alert pendants and “nanny cams” to monitor loved ones are not new. However, the aging population, coupled with the staffing shortage and the decrease of family caregivers is driving digital transformation and the development technology solutions that will transform LTC.

Technology-enabled solutions are improving remote patient monitoring and delivery. For example, the addition of assistive devices such as heart rate sensors on phones to telehealth further improves outcomes of remote healthcare delivery. For older adults living with chronic health conditions, remote monitoring tools offer a more complete picture – as opposed to snapshots during in-person visits. Data from a 2019 survey (Cambia, 2019) revealed that 64% of caregivers utilized a digital tool for managing caregiving responsibilities, with approximately 40% desiring further use of digital health solutions for care management.

Robots with Artificial Intelligence (AI) are helping people to remain independent for longer by having “conversations” and other social interactions to keep aging minds sharp. Systems that use data to make decisions (AI) coupled with sensors are able to collect data which is then analyzed by algorithms to infer actions or patterns in activities of daily living and detect when things are off. Imagine a fall, “wandering behavior,” or a change in the number or duration of bathroom visits that signal a health condition triggering an alert so intervention can be initiated before a serious condition develop!

Rapidly emerging technological advances hold great potential for older people and their caregivers in navigating the social, cognitive, and physical changes associated with aging. These technological advances have the potential to substantially alter workforce needs and potentially mitigate a portion of the rising workforce demand. Cutting-edge products and services may help people remain in their homes or assist long term care (LTC) facilities in their efforts to care for the aging via technology that can perform a variety of functions.

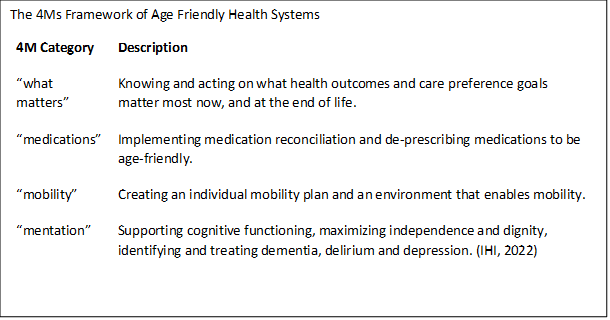

Age Friendly Care

Healthcare providers and health systems do not always focus on the issues and outcomes that matter most to older adults. Individuals seek healthcare not merely to improve disease-specific outcomes (such as blood pressure or blood sugar control) but to be able to do what they want in their daily lives. Physical, cognitive, psychosocial, and social functioning are the health outcomes that best reflect whether people are getting what they want from their healthcare. Unfortunately, these patient-centered functional outcomes do not appear in electronic health records (EHRs), generally do not determine payment or quality, and are largely ignored in most healthcare settings. This unfortunate disconnect is detrimental to all patients, and particularly older adults. The Age Friendly Health Systems movement exists to address this disconnect. The Age-Friendly Health System describes itself as a movement to recruit and support entire healthcare systems to focus on the domains most important to quality healthcare for older people. These domains are the “4Ms”: mobility, medications, mentation, and what matters.

This means making sure older people have a mobility plan when receiving medical care or in long term care; reviewing medications regularly to minimize harm; addressing conditions that affect thinking and are common in older people such as dementia, depression and delirium; and incorporating what matter to the person, such as their values, goals and preferences, into all care plans (Tinetti, 2022).

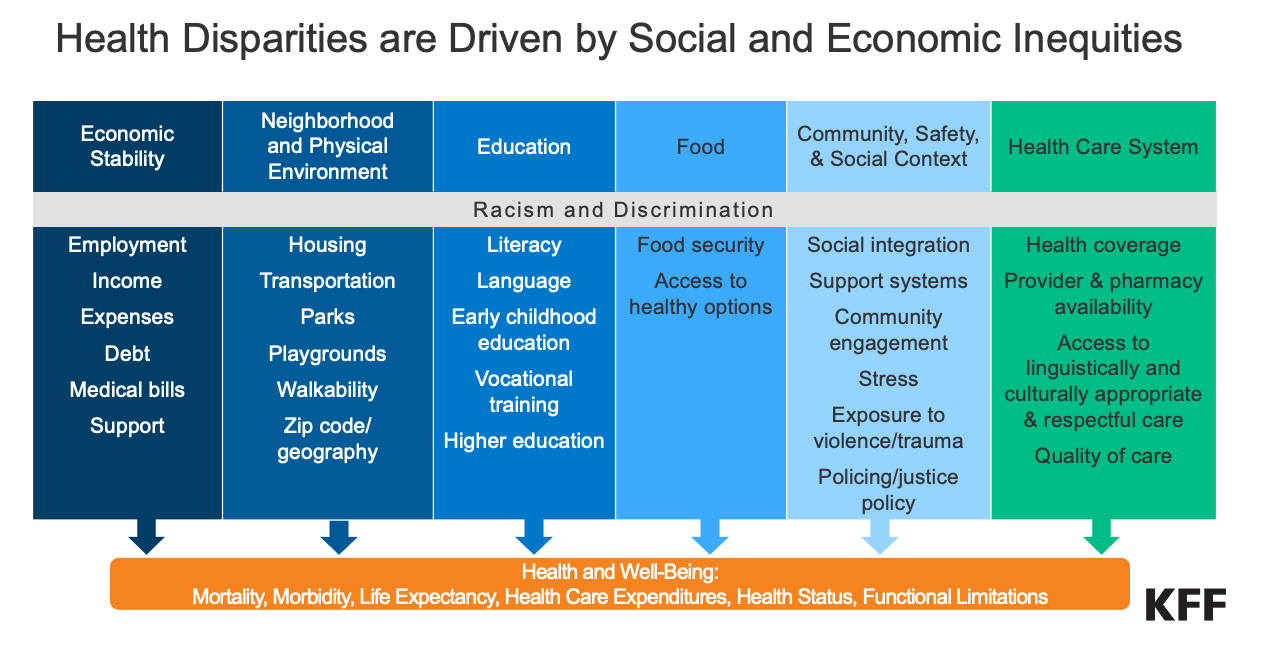

Addressing Disparities

There is a growing body of evidence documenting racial, ethnic, and class disparities in long term care (Konetzka & Werner, 2009; Gorges, 2018; Rizzuto & Aldridge, 2018; Morales, et. al., 2020; Lee et.al., 2021; Sloan et. al., 2021). In 2015, about 22% of those over 65 were members of minority groups; by 2050 that will increase to 39%. There are significant income disparities based on race and an accelerating gap between the median net worth of African-American and Latino families and that of white families (Sloan, 2020). The result is that seniors seeking long term care will be more likely to be racial or ethnic minorities and have fewer resources to pay for their care.

Assisted living, continuing care retirement communities and private-home health care are expensive and less accessible to seniors with lower incomes and fewer assets. Therefore, it is not surprising that the number of minorities in nursing homes has risen while the number of white residents has fallen as those that can afford to seek community based rather than institutional care. Racial and ethnic minorities are also more likely to live in facilities with fewer resources, lower staff nursing ratios and lower quality indicators (Shippee et al., 2018).

Although there are initiatives underway to increase the support for states to pay for home- and community-based services (HCBS) that could help address the disparities in access, studies have revealed disparities in the HCBS sector. Minority patients receiving home health care tend to have more adverse events, less functional improvement and worse patient experience. African-American and Hispanic patients receiving home health were found to be more likely to go to the emergency department or be readmitted to the hospital (Narayan & Scafid, 2017; Chase et al., 2018). Disparities exist in end-of-life care and pain management as well. African-Americans in hospice care are more likely to use the emergency department or to be hospitalized and African-Americans and Hispanics are less likely to be assessed and treated for pain (Johnson, 2013).

LTC facilities, hospices and palliative care specialists are working to increase culturally appropriate care, education and outreach to minority communities in an effort to address disparities. However, strides can only be made within the context of historic racism in employment and housing ownership, as well as patterns of housing segregation that contribute to the patient demographics in LTC.

Special populations

Dual Eligibles

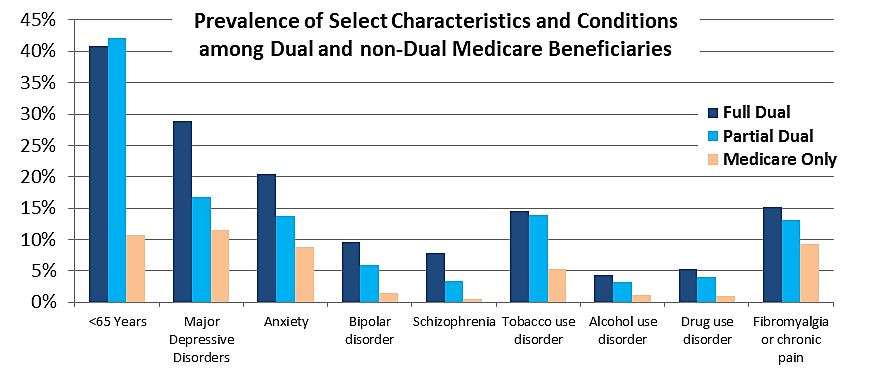

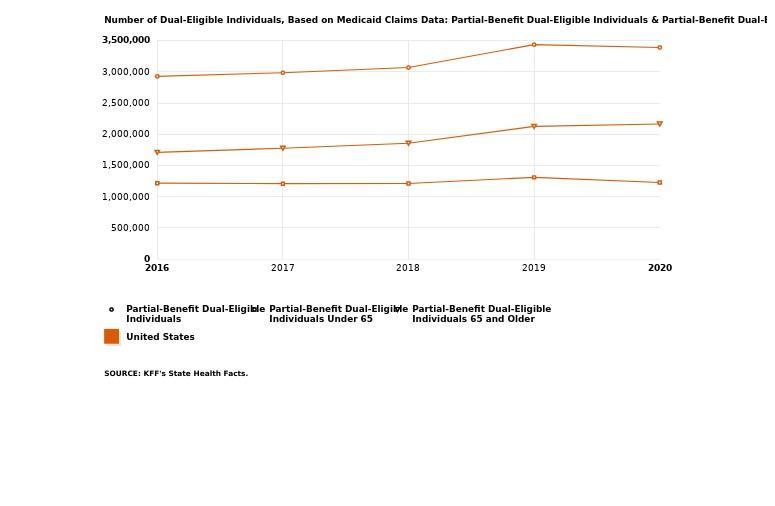

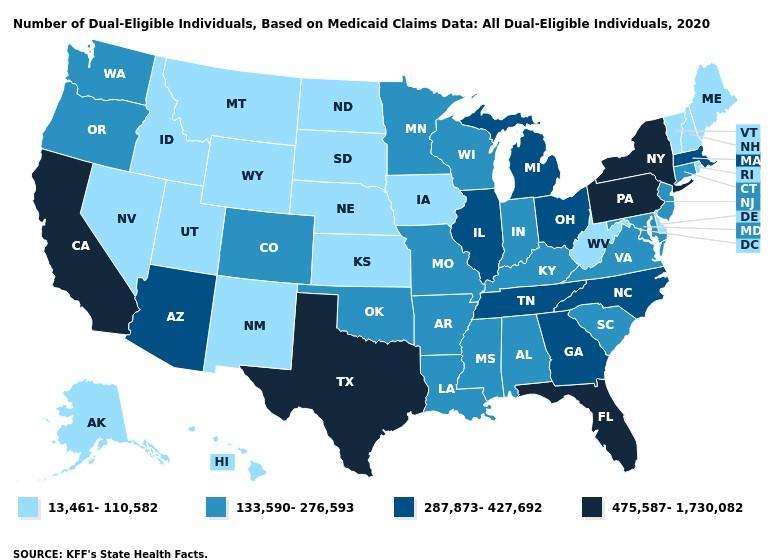

Twelve million people are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid. Known as “dual-eligible beneficiaries,” they account for 20% of Medicare beneficiaries and 15% of those receiving Medicaid, but account for one-third of total expenditures for each program. Most qualify for Medicare on the basis of age or a disability, and all dual eligible beneficiaries have incomes below or near the federal poverty level. This population suffers disproportionately from chronic conditions and fragmented care (MedPac. A Data Book: Health care spending and the Medicare program, July 2021).

Dual eligibles are enrolled in both programs when a Medicare enrollee’s income and assets are low enough to qualify them for Medicaid help in paying for some of the costs of Medicare – or to qualify them for full coverage under both Medicare and Medicaid. Note that the federal government oversees Medicare eligibility – meaning it is the same in each state. But states set their own eligibility rules for Medicaid and income limits for these programs vary widely.

These enrollees are commonly broken into two groups:

Full Duals – who have Medicare but also receive benefits under Medicaid

Partial Duals – who have Medicare but qualify to have Medicaid help pay for expenses such as Medicare premiums and/or cost-sharing

Source: Navigating Health Care as a “Partial Dual Eligible” United Healthcare 2019

Source: Navigating Health Care as a “Partial Dual Eligible” United Healthcare 2019

Full dual eligibles are entitled to receive all benefits covered by Medicaid, such as nursing home and other institutional care, home care, dental care, mental health care and therapy, eye care, transportation to and from providers, and prescription drug coverage. Half of full duals initially qualified for Medicare because of disability rather than age, and nearly one-fifth have three or more chronic conditions. Consequently, a sizable share of full duals, more than 40%, use long-term services and supports—a far greater percentage than for other Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries.

Partial duals are low-income by definition and have health care and social needs that differ from the broader Medicare population. Partial duals are considerably more likely than the broader Medicare population to have mental health needs such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. They also are younger than the broader Medicare population, more likely to have substance use disorders and chronic pain, more likely to use the emergency department, have a higher rate of potential preventable hospital admissions.

Knowledge CheckWhat is the difference between a full dual and a partial dual covered individual?

Racial/Ethnic Minorities

In 1985 the U.S. government conducted a widescale study to evaluate the health of racial and ethnic groups in the US. This was called the “Heckler Report” after the then Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Margaret Heckler. The Heckler Report found that each year, 60,000 deaths occurred each year due health disparities as a result of racial inequality. It outlined the six causes of death that accounted for more than 80% of mortality among ethnic and racial minorities (1) Cancer, 2) Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular disease, 3) Chemical Dependency, 4) Diabetes, 5) Homicide, suicide, and unintentional injury, and 6) Infant mortality and low birthweight) (Task Force, 1985). The report included recommendations to reduce these health disparities, as well as to collect data of a higher quality for Hispanics, Asian Americans, American Indians, and Alaska Natives (Gracia, 2018). This report directly led to the creation of The Office of Minority Health (Gracia, 2018). Their breakdown of racial and ethnic groups is how we will evaluate each group.

Black/African American

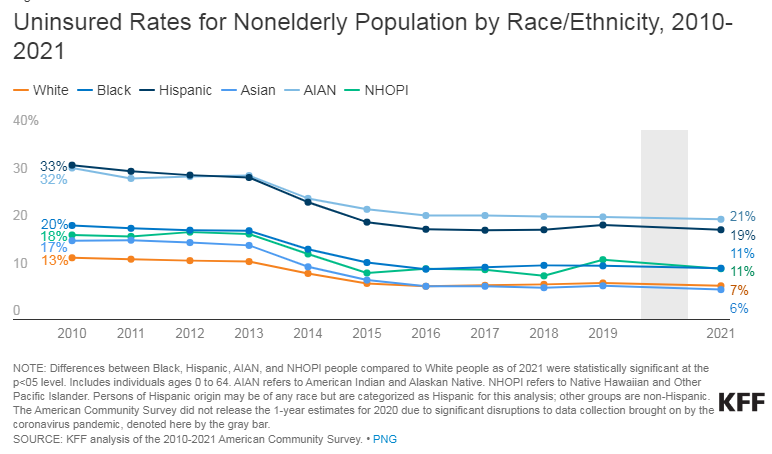

The death rate for Blacks/African Americans is on average higher than whites for heart diseases, stroke, cancer, asthma, influenza and pneumonia, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, and homicide. Life expectancy for blacks is 77.0 years, with 79.8 years for women, and 74.0 years for men. Compared to the white non-Hispanic population, the projected life expectancies is 80.6 years, with 82.7 years for women, and 78.4 years for men. Private health insurance coverage for blacks is 55.9% compared to 74.7% for white non-Hispanics. In 2019 10.1% of black non-Hispanics were uninsured while only 6.3% of white non-Hispanics were (Office of Minority Health. Black/African American – The Office of Minority Health, n.d.).

Hispanic/Latino American

Hispanics are the racial group with the highest rate of lack of insurance in the US. In 2019, the Census Bureau reported that 50.1 % of Hispanics had private insurance coverage, as compared to 74.7 % for non-Hispanic whites. Further data showed that 36.3 % of all Hispanics had Medicaid or public health insurance coverage, as compared to 34.3 % for non-Hispanic whites. Finally, nearly 20% of the Hispanic population was not covered by health insurance, as compared to 6.3 percent of the non-Hispanic white population. Additionally, the Hispanic population has higher rates of obesity than the white non-Hispanic population, and certain ethnic subgroups have disproportionately higher rates of Asthma and HIV/AIDS (Office of Minority Health. Hispanic/Latino – The Office of Minority Health, n.d).

Asian American

Asian Americans are most at risk for the following health conditions: cancer, heart disease, stroke, unintentional injuries (accidents), and diabetes. Asian Americans also have a high prevalence of the following conditions and risk factors: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis B, HIV/AIDS, smoking, Tuberculosis, and liver disease. Among the Asian group, the ethnic sub-groups really vary in terms of their insurance coverage rates, poverty levels, educational attainment levels, and their life expectancies (Office of Minority Health. Asian American – The Office of Minority Health, (n.d.).

Native Hawaiian & Pacific Islander American Health Profile

The tuberculosis rate in 2019 was 37 times higher for Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, with an incidence rate of 17.6, as compared to 0.5 for the white population. It is significant to note that in comparison to other ethnic groups, Native Hawaiians/ Pacific Islanders have higher rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity. This group also has less access to cancer prevention and control programs. Some leading causes of death among Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders include: cancer, heart disease, unintentional injuries (accidents), stroke and diabetes. Some other health conditions and risk factors that are prevalent among Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders are hepatitis B, and HIV/AIDS (Office of Minority Health. Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander – The Office of Minority Health, n.d.).

American Indian/ Native Alaskan

It is significant to note that American Indians/Alaska Natives frequently contend with issues that prevent them from receiving quality medical care. These issues include cultural barriers, geographic isolation, inadequate sewage disposal, and low income. Some of the leading diseases and causes of death among AI/AN are heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries (accidents), diabetes, and stroke. American Indians/Alaska Natives also have a high prevalence and risk factors for mental health and suicide, unintentional injuries, obesity, substance use, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), teenage pregnancy, diabetes, liver disease, and hepatitis (Office of Minority Health. American Indian/Alaska Native – The Office of Minority Health, n.d.). This population has a high rate of mental health conditions, specifically post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Emerson, et al, 2017), substance abuse (McDonell, et al, 2016), and suicidality (Kwon & Saadabadi, 2022). They are also at an increased incidence for certain general medical conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes (Carson, 2020).

Knowledge Check What was the seminal report in 1985 that examined the health of racial and ethnic groups?

Uninsured

In the United States, access to healthcare is often synonymous with having health insurance (Kirby, et al, 2022). Although the rate of uninsured Americans decreased under the ACA (Uberoi, et al, 2016), there has been a recent rise in the uninsured rate again (Morenz, 2021). This increase began prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, although that did not help matters. From 2017 to 2019, the uninsured rate rose by 1.7%, most likely as a result of various policy changes to the ACA and Medicaid (HHS, 2021). Since 2016, there has been a disturbing increasing trend in uninsured children in the US. The number of children who lacked consistent either private or public insurance coverage increased between 2016 and 2019 (Yu, et al, 2021) According to HHS, when compared to other Americans, the uninsured are disproportionately likely to be African American or Latino, be young adults, have low incomes, and/or live in states that have not expanded Medicaid (HHS, 2021). Different states are impacted disproportionately too. For example, one-third of the total increase of children without insurance between 2016 – 2019 occurred in the state of Texas (Alker & Corcoran, 2020). Trump administration policies which deterred immigrant families from enrolling eligible children (the children, most of whom are citizens are eligible) played a big role in this decline in states like Texas and Florida ((Alker & Corcoran, 2020). Some of the other variations were due to states which decided not to expand their Medicaid under the ACA (Larson, et al, 2020). Some of it is due to the variation of the availability of employer-sponsored coverage (particularly for low wage workers) from state to state (Dworsky, et al, 2022).

Women

Females have very different interactions with the healthcare system than their male counterparts. Women use health care more often for both mental and physical concerns, even after controlling for unique physiological considerations (e.g. pregnancy) (Thompson, et al, 2016). At any given age, males die in great numbers than females (Hossin, (2021). However, despite these facts, at virtually any given age, women report worse mental (Brown, et al, 2022) and physical health (Hossin, (2021). Despite this, there is still a lag in closing this gap, as there is a disproportionate amount of the federal research funds are spent on diseases that primarily affect men (Mirin, 2021).

Office on Women’s Health

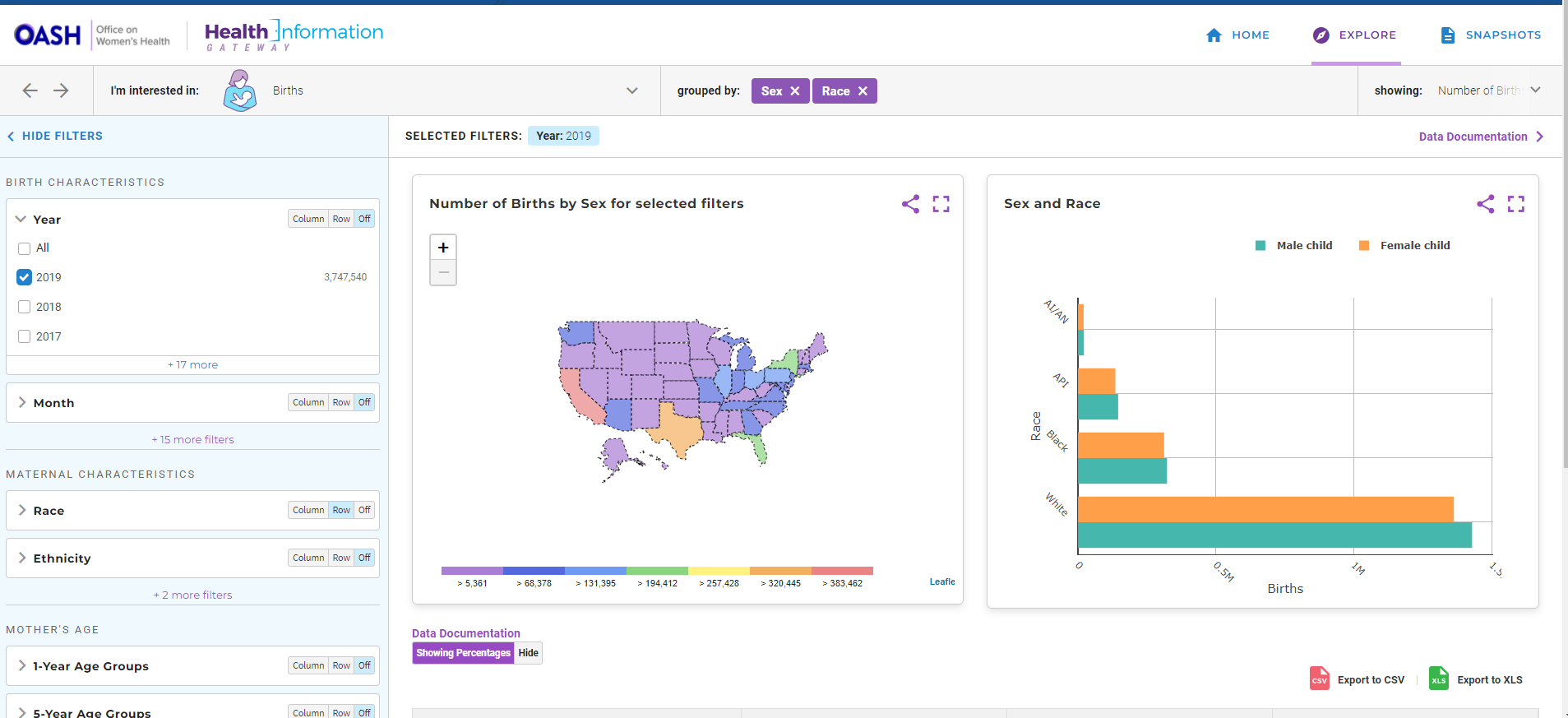

The Office on Women’s Health (OWH) is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and functions to improve the health and well-being of U.S. women and girls. The purpose of the OWH is to advance health and wellbeing of women across their entire lifespan. They have a wide range of programs and actives which they run to put focus on women’s health. They also provide open access data through their “Health Information Gateway” with very easy to use interface, as seen below.

Homeless/Unhoused

On any given night, it is estimated that more than half a million people in America are experiencing homelessness (Bensken, et al, 2021). Homelessness is a complex issue. While there is no international consensus on the definition of “homelessness” (Bedmar, et al, 2022), we will use the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development ‘s (HUD) definition of homeless which are individuals who fall into one of the four categories:

Categories of homeless include experiences of those who:

- Are trading sex for housing

- Are staying with friends, but cannot stay there for longer than 14 days

- Are being trafficked

- Left home because of physical, emotional, or financial abuse or threats of abuse and have no safe, alternative housing

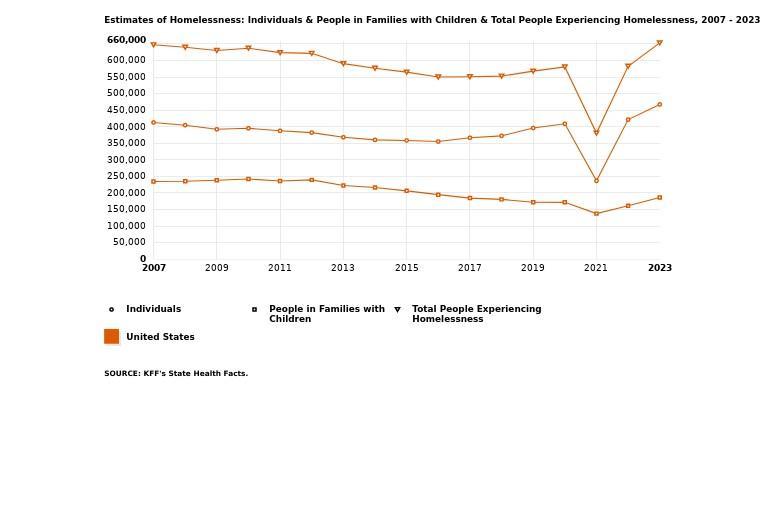

It is often more than just a lack of a place to live. Homelessness is a frequently the unfortunate consequence of the interactions of complex individual and structural societal factors (Allegrante & Sleet, 2021). It can be influenced by sudden changes in employment (Rew, et al, 2021), poverty, addiction, mental illness, lack of affordable housing (Allegrante & Sleet, 2021), and the recent COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased chronic homeless (Barocas, et al, 2021). There were many factors which went into this increase. Job layoffs increased 10-15 times as during the start of the pandemic as they had been before the pandemic (Flaming, et al, 2021). Before the pandemic, estimates were that eight million Americans spend half or more of their budget on rent which put them very at risk for becoming homeless if they lost their jobs or as soon as a moratorium on evictions ended (Coughlin, Sandel & Stewart, 2020).

While the exact numbers and profile of the homeless is always changing and unknown, we do have some estimates. According to HUD, on a single night, 18 out of every 10,000 people experienced homelessness. Six in ten of these individuals were in sheltered locations while the remaining 4 were unsheltered. The majority of the homeless households are adults only (70%), however 30% of families experiencing homelessness did so with at least one child under the age of 18. Almost nine out of ten homeless individuals are over 25 years of age. Six out of ten of the homeless identified as men (61%), with 39% identifying as women and 1% identifying as transgender or gender non-conforming. Almost half of the homeless population is white, with 39% of the population reporting as African American, and nearly a quarter (23%) reporting as Hispanic or Latino. Slightly more than half of all homeless people in the US were in one of the 50 largest US cities (HUD, 2020).

The homeless frequently suffer from poor health and premature death (Bedmar, et al, 2022). Life expectancy can be up to 30 years less for those without homes (Serme-Morin, et al, 2018). Up to 80% of the homeless have a mental health condition or drug addiction (Bedmar, et al, 2022). Additionally, they are more likely to have chronic medially conditions and have complications with these conditions compared to the general public because they are not treating these medical conditions (Bernstein, et al, 2015). They are more suspectable to diseases such as COVID-19 (Barocas, et al, 2021). Homeless women also have an increased risk for gender related violence (Calvo, et al, 2021).

Knowledge CheckWhat percentage of unhoused individuals are families with children?

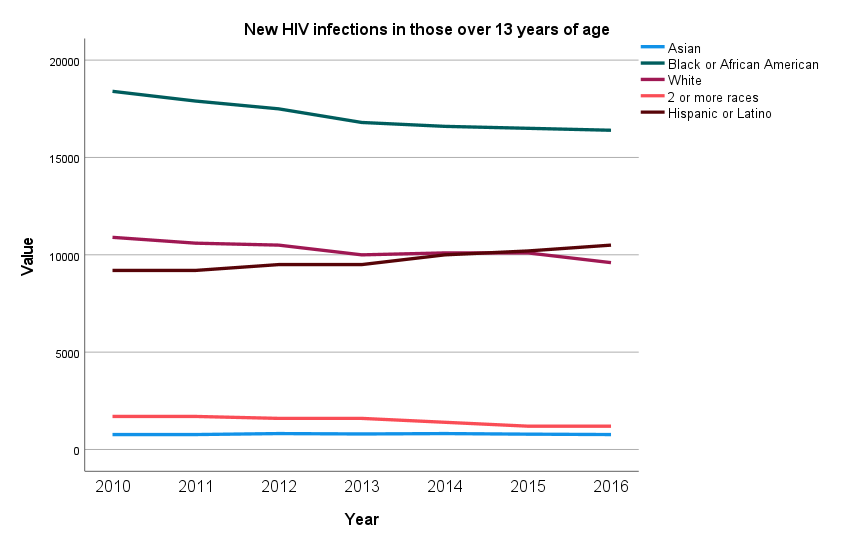

HIV

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) impacts all Americans; however, the HIV epidemic disproportionately impacts certain populations. While it is nowhere near as bad as it once was and we do have some limited treatments, it is of great concern (Sullivan, et al, 2021). One community is intravenous drug users (Stojanovski, et al, 2021). In the 40 years since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, nearly three quarters of a million people have died of HIV/AIDS. Of these, although African Americans represent 13% of the US population, they have represented 41% of the deaths (Sullivan, et al, 2021). Similarity, although Latinos make up 16% of the US population, they make up 20% of all new HIV cases, resulting in an infection rate almost three times as high as whites (Prejean, et al, 2011). Those in the LGBTQ community, particularity men who have sex with men, are at high risk for new cases of HIV (Mayer, et al, 2021). Transgender individuals are also at an increased risk for HIV. Both trans masculine and trans feminine individuals are at an increased risk, with odds ratios of having HIV being 6.8 and 66 respectively according to one meta-analysis (Stutterheim, et al, 2021).

Data Source: National HIV Surveillance System (NHSS); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (CDC/NCHHSTP) Date accessed [May 10, 2022]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020/hp2020-errata-page.htm

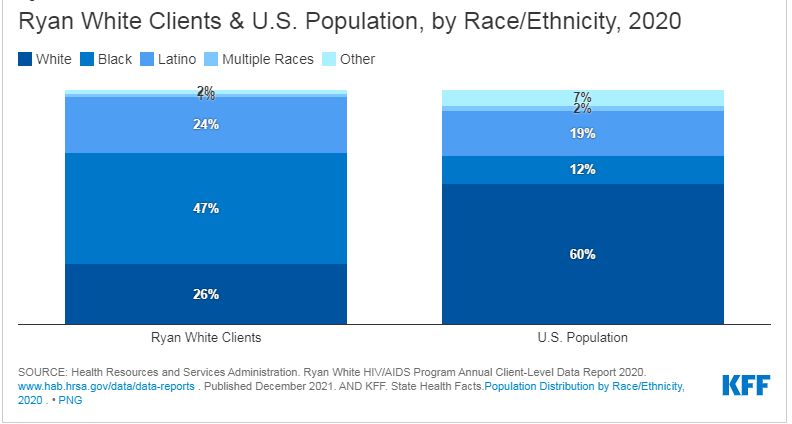

The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program was first enacted in 1990. The Ryan White program is the largest federal program designed specifically for people with HIV and serves over half of all those diagnosed (Weeks, et al, 2022). The program is the third largest source of federal funding for HIV care in the US, just behind Medicare and Medicaid. It is the largest source of HIV discretionary funding. Funding is distributed to states/territories, cities, and HIV organizations in the form of grants.

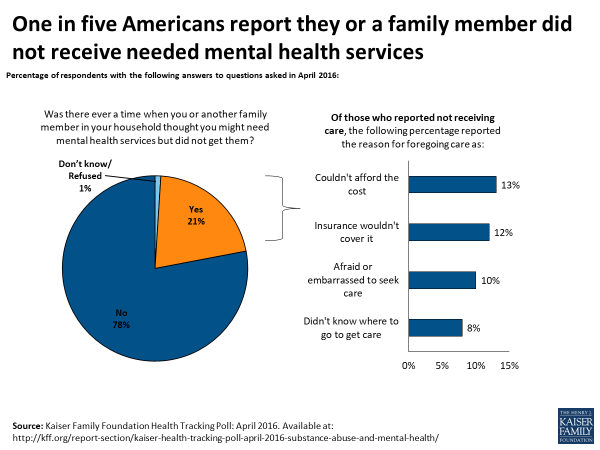

Mental Health Conditions

As identified in the Healthy People 2030 initiative, nearly half of all the US population will be diagnosed with a mental health condition at some point in their lives (Mental Health and Mental Disorders. Mental Health and Mental Disorders – Healthy People 2030, n.d.) Mental health conditions do not discriminate; they impact people of all ages, races, and socioeconomic statuses (Brunoni, et al, 2021). According to the National Institute of Mental Health, at any given time, nearly one in five adults live with a mental illness (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). Mental health conditions can range from mild to severe. The COVID pandemic was found to be particularly difficult for some people with anxiety and depression disorders, causing extra distress (Iasevoli, et al, 2021). There is also evidence that a person’s mental health can impact their physical health, both via changes in behaviors because of the mental health condition and because of more indirect pathways (Robson & Gray, 2007). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services which offers resources for those suffering from mental health conditions or substance abuse. They also offer data sets, including the National Mental Health Service Survey which is an annual survey of facilities in the US providing mental health treatment (SAMHSA, n.d.).

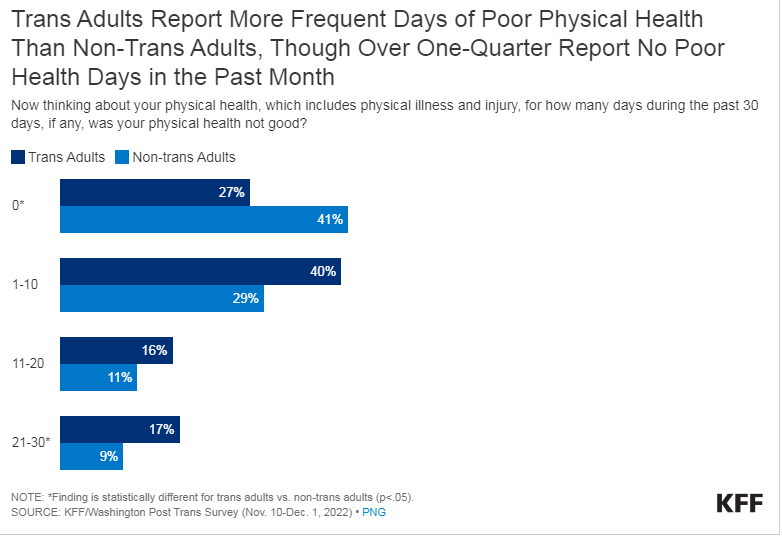

LGBTQ+

The American Academy of Family Physicians American Family Physician includes gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender persons in their definition of populations with special needs (AAFP, 2021). There are many acronyms to designate sexual orientation and gender identity diversity, however the most commonly used one is “LGBTQ” which stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning. Although this is far from inclusive and the acronym is always evolving, this is often a shorthand term used to signify a discussion of the LGBTQ community as a whole (OK2BME (n.d.).

There are many concerns in common with this population that there are with the other populations, such as unconscious bias and barriers to access. However, the way they present are unique in the group. For example, they have had a uniquely changeling history interfacing with the medical establishment and many slang terms are still used in describing the lifestyle and people involved in the LGBTQ community which some people can find offensive (Bass & Nagy, 2022). On the provider’s side, there is also often a lack of education in the terminology, a lack of understanding of typical behaviors, and population specific medical interventions such gender modification surgeries or hormone therapy, or frequently used alternative medications such as black-market hormones (Bass & Nagy, 2022). It is simply a lack of education, but many medical students do not feel confident treating the LGBTQ community, despite the majority of medical students expressing a desire serve this population (Arthur, et al, 2021).

Due to many sociocultural issues including those listed above, those in the LGBTQ community often have difficulty opening discussing health related issues with their medical providers (Karakaya & Kutlu, 2021) and with their families (Flores, et al, 2022). They are more likely to avoid medical providers than the general population because of fears of discrimination (Kates, et al, 2018). This is probably a contributing factor to the high rate of mental health conditions in this population. LGB adults are almost twice as likely to experience mental conditions as heterosexual adults (Medley, et al, 2016) and Transgender adults are nearly four times more likely than cisgender (people whose gender identity corresponds with their birth sex) individuals to experience a mental health conditions (Wanta, et al, 2019). They are also more likely to die by suicide. It is important to note that sexual minorities are not inherently more likely to develop negative mental health outcomes. Rather, the elevated risk for mental conditions is likely the result of chronic LGBTQ-specific stressors, such as discrimination and harassment (Frost & Fingerhut, 2016). Another mental health risk the LGBTQ community is at risk for is death by suicide (Kaniuka, et al, 2019), with the transgender community being the most at risk. Almost half of transgender adults say that they have considered death by suicide in the last year, compared to 2% of the general population (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016).

Long Term Care & Special Populations Discussion Questions

1.What is the main goal of long term care?

2.How do formal and informal long term care differ? What is the importance of informal care in LTC delivery?

3.What is meant by the “continuum of care” in LTC? Discuss services delivered in facilities, homes and the community.

4.Who are the primary users of LTC/ What is the projected growth for this population?

5.Describe home and community based services and how these are financed.

6.Go to https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Enter any zip code you want and compare any three nursing homes you want. Do they all participate in Medicaid? Are they all non-profit? How many beds do they have? How many stars do they each have? How do the total number of nurse staff hours per resident per day compared to the state and national average? What are some other noticeable differences?

7.What might be some reasons for the different health outcomes between the average Medicare recipient and the average dual eligible recipient?

8.Black/African American mothers have significantly higher maternal mortality in the United States (see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/maternal-mortality-rates-2020.htm) than other racial groups. Given what was covered in the chapter, what might be some of the possible reasons for this disparity?

9.It is implied in the chapter that COVID-19 did not help the uninsured rate. Why specifically would a pandemic like COVID have impacted the uninsured rate in the United States?

10.Do some research online. How are elderly adults impacted by homelessness?

Student resources

GLMA (Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality): https://www.glma.org/

Health Equity in Healthy People 2030: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-equity-healthy-people-2030

HIV.gov: https://www.hiv.gov/

Healthy People 2030 – Mental Health and Mental Disorder: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/mental-health-and-mental-disorders

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation: Long-Term Care in the United States: A Timeline: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/timeline/long-term-care-in-the-united-states-a-timeline/

The Joint Commission Nursing Care Accreditation: https://www.jointcommission.org/accreditation-and-certification/health-care-settings/nursing-care-center

Mental Health America: https://www.mhanational.org/issues/lgbtq-communities-and-mental-health

National Association of Free & Charitable Clinics | NAFC: https://nafcclinics.org/

National Institute on Aging. Health Information: – https://www.nia.nih.gov/health

National Center for Health Statistics Public-Use Data Files and Documentation: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/ftp_data.htm

National Alliance on Mental Health: https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/LGBTQI

Office on Women’s Health: https://www.womenshealth.gov/

Office on Women’s Health, Health Information Gateway: https://gateway.womenshealth.gov/

Substance and Mental Health Administration Mental Health guide: https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development Homelessness Resources: https://www.hud.gov/homelessness_resources

Key Words

Caregiver. A person who provides help to an individual who requires assistance with daily living due to old age, disease, a mental disorder, or disability. Caregivers can be paid, but are often unpaid family members or other persons from the individual’s social network. Typical tasks of caregivers include helping the individual to eat, bathe, dress, and use the toilet, as well as pay bills, clean the house, manage medicine, and monitor health. Caregiving can be highly stressful for caregivers, especially when caring for someone who is severely disabled or suffers from mental problems.

Disparities. Healthcare disparities are differences in access to or availability of medical facilities and services and variation in rates of disease occurrence and disabilities between population groups defined by socioeconomic characteristics such as age, ethnicity, economic resources, or gender and populations identified geographically.

Life Expectancy. Actuarial determination of how long, on average, a person of a certain age is likely to live.

Paraprofessionals. Personnel, such as certified nursing assistants and therapy aides, who provide basic assistance with activities of daily living and/or assist licensed and professional staff.

Home Health. A wide range of health care services that can are provided in the home for an illness or injury. Services include nursing, therapy, and health-related homemaker and social services.

Home Care. Help with daily activities to allow people to stay at home. Home care is sometimes called personal care, companion care, custodial care or homemaker services.

Functional limitation. The restriction or lack of ability to perform an action or activity in the manner or within the range considered normal that results from impairment. Usually applies when an individual does not have the physical, cognitive or psychological ability to independently perform the routine activities of daily living.

Cognitively impaired. When a person has trouble remembering, learning new things, concentrating, or making decisions that affect their everyday life.

Rehabilitation. A set of interventions /therapies that restore lost functioning or optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions.

The Joint Commission. An independent, not-for-profit organization, previously called the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JACHO), that sets standards and accredits healthcare facilities.

Hospice. Services that focus on the care, comfort, and quality of life of a person with a serious illness who is approaching the end of life. Services include a blend of medical, spiritual, legal, financial, and family support. Services can be provided in a specialized facility, a nursing home or the patient’s own home.

Palliative Care. Specialized medical care for people living with a serious illness. This type of care is focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of the illness and can include curative treatment. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the family.

Advanced Directives. A legal document that states a person’s wishes about receiving or withdrawing medical care if that person is no longer able to make medical decisions because of a serious illness or injury.

Telehealth. The use of digital information and communication technologies, such as computers and mobile devices, to access health care services remotely, to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration.

AI (Artificial Intelligence). AI is a wide-ranging branch of computer science concerned with building smart machines capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence.

References

AARP, (2021). Aging in place: A state survey of livability policies and practices. Retrieved February 3, 2022, from: Aging in Place: A State Survey of Livability Policies and Practices (aarp.org).

Administration for Community Living. (2020). Long term care.gov. Retrieved February 1, 2024 from https://acl.gov/ltc/basic-needs/how-much-care-will-you-need

AHCA & NCAL. (September 2021). State of the long term care industry: Survey of nursing home and assisted living providers show industry facing significant workforce crisis [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/APA/lecture.

Alker, J., & Corcoran, A. (2020). Children’s uninsured rate rises by largest annual jump in more than a decade. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families.

Allegrante, J. P., & Sleet, D. A. (2021). Investing in public health infrastructure to address the complexities of homelessness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8887.

Allen, K. (2021, June 4). Long-term care and care facilities post-COVID-19 pandemic. HMA Blog. Retrieved February 16, 2022, from https://www.healthmanagement.com/blog/long-term-care-and-care-facilities-post-covid-19-pandemic/

Alliance for Home Health Quality Innovation. (2020). Home health chartbook 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2022, from: https://ahhqi.org/images/uploads/AHHQI_2020_Home_Health_Chartbook_-_Final_09.30.2020.pdf.

American Academy of Family Physicians. (2021, December 15). Care of special populations. Care of Special Populations – American Family Physician. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.aafp.org/afp/topicModules/viewTopicModule.htm?topicModuleId=45

Arthur, S., Jamieson, A., Cross, H., Nambiar, K., & Llewellyn, C. D. (2021). Medical students’ awareness of health issues, attitudes, and confidence about caring for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 1-8.

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). (2022). Comparing new flexibilities in Medicare Advantage with Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports: Final Report. Retrieved January 31. 2024 from fromhttps://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/03390244d012ecbbe80e81d5c972bf39/medicare-advantage-medicaid-ltss.pdf

Bass, B., & Nagy, H. (2022). Cultural Competence in the Care of LGBTQ Patients. In Statpearls. essay, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Barocas, J. A., Jacobson, K. R., & Hamer, D. H. (2021). Addressing the COVID-19 pandemic among persons experiencing homelessness: steps to protect a vulnerable population. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(5), 1416-1417.

Bedmar, M. A., Bennasar-Veny, M., Artigas-Lelong, B., Salvà-Mut, F., Pou, J., Capitán-Moyano, L., … & Yáñez, A. M. (2022). Health and access to healthcare in homeless people: Protocol for a mixed-methods study. Medicine, 101(7), e28816.

Bensken, W. P., Krieger, N. I., Berg, K. A., Einstadter, D., Dalton, J. E., & Perzynski, A. T. (2021). Health Status and Chronic Disease Burden of the Homeless Population: An Analysis of Two Decades of Multi-Institutional Electronic Medical Records. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 32(3), 1619-1634.

Bernstein, R. S., Meurer, L. N., Plumb, E. J., & Jackson, J. L. (2015). Diabetes and hypertension prevalence in homeless adults in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), e46-e60.

Bestsennyy, O., Chmielewski, M., Koffel, A., & Shah, A. (February, 2022). From facility to home: How healthcare could shift by 2025. McKinsey & Co. Retrieved on January 10, 2022, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/from-facility-to-home-how-healthcare-could-shift-by-2025.

Brown, M. J., Hill, N. L., & Haider, M. R. (2022). Age and gender disparities in depression and subjective cognitive decline-related outcomes. Aging & Mental Health, 26(1), 48-55.

Brunoni, A. R., Suen, P. J. C., Bacchi, P. S., Razza, L. B., Klein, I., Dos Santos, L. A., … & Benseñor, I. M. (2021). Prevalence and risk factors of psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses before and during the COVID-19pandemic: findings from the ELSA-Brasil COVID-19mental health cohort. Psychological medicine, 1-12.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, (2021, September 8) Occupational outlook handbook. Retrieved February 5, 2022, from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home.htm

Calvo, F., Watts, B., Panadero, S., Giralt, C., Rived-Ocaña, M., & Carbonell, X. (2021). The prevalence and nature of violence against women experiencing homelessness: a quantitative study. Violence Against Women, 10778012211022780.

Cambia Health Solutions (2019). Wired for care: The new face of caregiving in America. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from Cambia Wired for Care Whitepaper.pdf (cambiahealth.com).

Carron, R. (2020). Health disparities in American Indians/Alaska Natives: Implications for nurse practitioners. The Nurse Practitioner, 45(6), 26-32.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). 2021. Home- and community-based services. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/LTSS-TA-Center/info/hcbs

Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey (ACS). Retrieved February 1, 2024 from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

Coughlin, C. G., Sandel, M., & Stewart, A. M. (2020). Homelessness, children, and COVID-19: A looming crisis. Pediatrics, 146(2): e20201408.

Donnelly, N. A., Sexton, E., Merriman, N. A., Bennett, K. E., Williams, D. J., Horgan, F., Gillespie, P., Hickey, A., & Wren, M. A. (2020). The prevalence of cognitive impairment on admission to nursing home among residents with and without stroke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7203.

Dworsky, M. S., Eibner, C., Nie, X., & Wenger, J. B. (2022). The Effect of the Minimum Wage on Employer-Sponsored Insurance for Low-Income Workers and Dependents. American Journal of Health Economics, 8(1), https://doi.org/10.1086/716198

Emerson, M. A., Moore, R. S., & Caetano, R. (2017). Association between lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder and past year alcohol use disorder among American Indians/Alaska Natives and Non‐Hispanic Whites. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(3), 576-584.

Flaming, D., Orlando, A., Burns, P., & Pickens, S. (2021). Locked out: unemployment and homelessness in the COVID economy. Available at SSRN 3765109.

Flores, D. D., Greene, M. Z., & Taggart, T. (2022). Parent-child sex communication prompts, approaches, reactions, and functions according to gay, bisexual, and queer sons. International Journal of Environmental Public Health, 19(1), 74.

Frost, D. M., & Fingerhut, A. W. (2016). Daily exposure to negative campaign messages decreases same-sex couples’ psychological and relational well-being. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(4), 477-492.

Grabowski, D. (2020, August). Strengthening nursing home policy for the post pandemic world: How can we improve residents’ health outcomes and experiences? Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/aug/strengthening-nursing-home-policy-postpandemic-world

Gracia, J. N. (2018, November 16). Remembering Margaret Heck ’er’s commitment to advancing Minority Health: Health Affairs Forefront. Health Affairs. Retrieved March 8, 2022, from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20181115.296624/full/

Hado, E., & Komisar, H. (2019, August 26). Long-term services and supports. AARP Public Policy Institute Fact Sheet. Retrieved January 20, 2022, from: arp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/08/long-term-services-and-supports.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00079.001.pdf

Hamel, L., Wu, B., & Mollyann, B. (2017, April 27). Views and experiences with end-of-life medical care in the U.S. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved February 2, 2022, from https://www.kff.org/other/report/views-and-experiences-with-end-of-life-medical-care-in-the-u-s/

Harris-Kojetin, L. (2019). Long-term care providers and services users in the United States, 2015-2016. Vital and health statistics. Series 3, Analytical and epidemiological studies, no 43;DHHS publication ; no. 2019-1427; https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/76253 https://aginginplace.org/adult-day-care/ Updated 2022

Hawes, K. (1996, December 1). Assuring nursing home quality: The history and impact of federal standards in OBRA-87. Commonwealth Fund Reports, Dec. 1996.

He, W., Goodkind, D., & Kowal, P. (2016). U.S. Census Bureau, International Population Reports, An Aging World: 2015, U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington, DC.

Health and Human Services, Office of Health Policy, Finegold, K., Conmy, A., Chu, R. C., Bosworth,, A., & Amp; Sommers, B. D., (2021). HP-2021-02 Trends in the US uninsured population, 2010-2020.

Help Guide. (2021, January). Independent living for seniors. Retrieved January 21, 2022, from https://www.helpguide.org/articles/senior-housing/independent-living-for-seniors.htm.

Hossin, M. Z. (2021). The male disadvantage in life expectancy: can we close the gender gap? International Health, 13(5), 482-484.

Housing and Urban Development, office of community planning and development, Henry, M., de Sousa, T., Roddey, C., Gayen, S., & Bednar, T. J., (2020). The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress (n.d.).

Hua, C. l., Cornell, P.Y., Zimmerman, S., Winfree, J., & Thomas, K. S. (2021). Trends in serious mental illness in US assisted living compared to nursing homes and the community: 2007–2017. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29: 434-444.

Iasevoli, F., Fornaro, M. ’ D’Urso, G., Galletta, D., Casella, C., Paternoster, M., … & COVID-19in Psychiatry Study Group. (2021). Psychological distress in patients with serious mental illness during the COVID-19outbreak and one-month mass quarantine in Italy. Psychological Medicine, 51(6), 1054-1056.

IHI (Institute for Healthcare Improvement). (July, 2020). Age-Friendly health systems: Guide to using the 4Ms in the care of older adults. Retrieved February 3, 2022, from: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHIAgeFriendlyHealthSystems_GuidetoUsing4MsCare.pdf

Institute of Medicine. (2001). Improving the quality of long-term care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9611.