6

6 – Financing Healthcare in the USA

Raymond Higbea, PhD, FACHE, FHFMA

Lara Jaskiewicz, PhD, MPH, MBA

Greg Cline, PhD

Grand Valley State University

“I think we do better as a country when we go step by step toward a goal, and the goal in this case should be reducing health care costs.” – Lamar Alexander

Learning Objectives

- Understand the historical context and development of payment for healthcare services in the United States.

- Understand the development of third-party payment tools and methods.

- Understand the link between government health policy and payment.

- Understand how the introduction of third-party payment fosters the growth of healthcare spending.

Introduction

This chapter discusses the evolution of payment for medical care in the United States from a system where individuals and physicians interacted on a personal level to determine appropriate payment to a system where payment decisions are determined by a private or public third party. The remainder of the chapter discusses the development of these payment tools and methods over the past 150 years and how the cost of medical care has dramatically increased following their introduction.

History of Financing Healthcare

The financing of healthcare has evolved with advancements in medical sophistication, technology, and the demographic shift of populations from rural communities to urban centers that began with the advent of the industrial revolution during the mid-nineteenth century. These demographic shifts were more pronounced in the eastern United States than the expansion in the western states that followed suit as their populations grew and the need for urban commercial centers emerged.

The Barter System

Regardless of the demographic location, the primary method of payment up to the mid-nineteenth century was barter. An individual seeking treatment from a physician would enter a monetary or barter agreement as payment for services. Frequently, physicians adjusted their price based upon their perception of the patient’s ability to pay. Individuals seeking hospital care during this time would often need to pay or make arrangement to pay the full amount prior to receiving services. It must be noted that neither physicians nor hospitals had much to offer those seeking treatment in the mid-1800s, and most healthcare was carried out at the patient’s home.

Prepaid Plans and Sickness Funds

The latter half of the nineteenth century was an era of growth for manufacturing, mining, lumbering, and railroad industries in the United States and Western Europe. These occupations were very dangerous with few, if any, safety or environmental regulations. In addition, these forms of work drew workers away from family homesteads and support to congregated and congested living environments, some of which were far from any town. As a result of these shifts in societal organization and family support, employees had little to no family support during times of recovery from illness or injury. To remedy this situation mining, lumbering, and railroad companies developed prepaid plans to cover the medical needs of their employees. Often these plans were implemented through the “company doctor” who would reside either in the work camps or communities established by the employers who provided medical care for the employee only and not their families (Murray, 2007).

The medical payment option that developed for manufacturing employees were sickness funds. These funds were sponsored by either the employer or union and did not pay for medical care. Rather, they paid a portion of the employee’s wage once the employee was certified as sick or injured. Thus, sickness funds were more like disability insurance than medical insurance. During this era, two phenomena drove the need for sickness funds – recovery time and the need for income. The normal duration of recovery from illness or injury was 4-6 weeks and if you did not work, you did not get paid – thus illness or injury resulted in a lack of income. Employees with an illness had to be certified as ill by a physician one week following onset of the illness. Interestingly, there were fewer employees certified as ill by the physician supporting a manufacturer’s sickness fund than by physicians supporting a union sickness fund. Sickness funds were paid for by employees at the cost of 50 cents per month or 1 percent of wages, and once an employee was certified as sick, the employee received a portion of their wages throughout the duration of the illness (Murray, 2007).

During this same era, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck of Germany implemented three social insurance laws: National Health Plan for workers (1883), Accident Insurance (1884), and Old Age and Disability Insurance (1889). The German Health Insurance Plan is also known as sickness funds; however, these funds are health insurance funded by employer and employee contributions. Accident insurance and Old Age and Disability Insurance were precursors to Workers Compensation and Social Security in the United States.

Early Government Involvement

Early U.S. government involvement in health financing was largely through the military. Medical services were provided to soldiers as well as to specific populations during outbreaks of disease. For example, US Army surgeons treated Native American tribes suffering from smallpox epidemics during the early 19th century (National Library of Medicine, 1998). The U.S Public Health Service Commissioned Corps got its start in the late 18th century within the Marine Hospital Service, and initially focused on providing healthcare to sailors and immigrants (US Public Health Service, n.d.). Several hospitals were established in major port cities on the East Coast to provide care to these travelers. However, government involvement in healthcare was largely limited to preventing the spread of disease in high-risk populations.

During the latter half of the 19th century society began to recognize some of the negative effects of the industrial revolution and resulting increase in urban growth. The government and community organizations attempted to address these negative societal trends by implementing programs and policies to build a better society. Building a better society was the theme of the Progressive party that sought to do so through developing a more professional government and the centralization of government functions, with one of those centralized functions being the provision of health care services for all residents funded and administered by the federal government. Two of the challenges the Progressives faced were that sickness plans were very effective at providing income that would be lost by not working during recovery and a large enough portion of the United States citizens disagreed with their centralization approach they did not have enough political support to pass these laws (Murray, 2007; Leonard, 2016).

During this period, United States residents did not have access. to regular health care services as we know them today. Rather, they had access to medical care when they were ill and needed help coping with the symptoms. They paid for their medical services out-of-pocket. Additionally, during this period physicians were vehemently opposed to anyone intervening in the relationship they had with their patients and carried out several vigorous campaigns to block the federal government’s entrance into payment for medical care. In 1935, during the Great Depression, the original Social Security legislation included a national health insurance program. Physician opposition was so vehement that if President Roosevelt had not removed that portion of the legislation at the last minute, the Social Security legislation would not have passed.

History of the US Government’s Role in Health Insurance

During the early part of the 20th century, the United States federal government unsuccessfully attempted on several occasions to introduce a national health insurance plan. Other than military health, all other national healthcare legislative attempts by the federal government failed until passage of the Kerr-Mills bill (PL 86-778) in 1960 that was a model for what would eventually become Medicaid. In 1965, Medicare and Medicaid legislation were passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by President Johnson. These two government-sponsored programs cover certain medical services for the retired or disabled (Medicare) and low-income (Medicaid) populations. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA – PL 111-148) was enacted to bend the cost curve through the enactment of insurance reform (e.g., ensuring that employers with 50 or more employees offer a minimum level of medical (health) insurance coverage to employees, thereby providing medical (health) insurance coverage to approximately 55% of Americans (BLS.gov) and many of their families) and the tighter linking of patient outcomes or quality to payment. The PPACA also allowed states to expand the income eligibility for Medicaid coverage to 138% of the federal poverty level.

Medicaid is a federal / state cooperative agreement, with the state needing to vote into law the agreement to provide Medicaid for its residents. States agreeing to provide Medicaid for their residents agree to administer the program and provide a minimum set of healthcare services based upon income eligibility (less than 133% of the federal poverty level with expanded Medicaid, less than 100% in states that did not expand Medicaid) and demographic characteristics such as female, pregnant female, child, disabled, and lower-income older adult. The federal government provides a sliding scale level of support for the program ranging from 50% – 78% based on the state per capita income with states with the lowest per capita income getting the highest matching level. Providers are often reluctant to take patients on Medicaid due to the low payment rate of approximately 40% of billed charges. In an effort to control administrative costs, most states moved their Medicaid populations to Medicaid Managed Care contracts during the 1990s (Medicaid, nd).

Passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010 increased eligibility for Medicaid coverage to a variety of demographic groups with the largest group being single men and the next group being older adults. As often stated, to be eligible for Medicaid pre-ACA one had to be lower-income alongside another disadvantaged catagory (e.g., female, child, old, disabled); post-ACA only needed to be lower-income. Post-ACA federal match for new or expansion enrollees was increased to 100% and moved over time to 90%.

Medicaid provides health care payment for eligible recipients with the four largest expenditure categories including hospitals, physicians and clinics, retail prescriptions, and long- term care totaling 77% (1980) to 78% (2022) (National Healthcare Expenditures, 2022) of total Medicaid expenditures. Hospitals expenditures as a percent of total Medicaid expenditures have been very consistent during this time increasing from 35% to 33%. Physicians and clinics have also been relatively consistent during this period with total expenditures ranging from 9% (1980) to 11% (2000) then bumping up post-ACA to 14% in 2020 to 2022. Retail prescriptions have been the most volatile of these categories, increasing from 5% (1980) to 7% (1990) then peaking at 10% (2000) then decreasing to 5% to 7% for 2010 and 2022. Nursing home expenditures as a percent of total Medicaid expenditures have decreased from 77% (1980) to 64% (2020) and then down to 24% in 2022 while home health expenditures have increased from 1% (1980) to 7% (2020) and then down to 5% in 2022 thus explaining most (83%) of the change in overall Medicaid expenditures. Long-term care (nursing homes) is a unique area of Medicaid expenditures where individuals requiring long-term care frequently enter care facilities under Medicare, private insurance, or self-pay. Once an individual has exhausted these private funding options and only has minimal remaining personal assets (i.e., house, car, and minimal savings) and are therefore considered impoverished they transition to Medicaid for the remainder of their long-term care stay.

Medicare is divided into parts A, B, C, and D with parts A and B included in the original passage of the Medicare legislation, part C added in 1993, and part D added in 2003. Medicare part A is hospital coverage that all Medicare recipients receive at no cost and was originally based on the 1960 Blue Cross plan. Over time, part A expanded to include not only the aged but also individuals certified as disabled and individuals with end stage renal disease. Initially, part A was paid on a cost-plus fee-for-service basis with minimal oversight. Hospitals found this to be a rich source of income and quickly embraced Medicare as a payment mechanism. This rich payment method and rapid adoption by hospitals fueled a rapid rise in medical inflation that has been unsuccessfully addressed by a number of administrative and legislative actions. Two of the most significant cost-control actions have been the implementation of the Preferred Provider Payment System, i.e., Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs), Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC), and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes) and the Medicare 1115 waiver program products originally developed in the 1990s. The development of DRG and APC codes was based upon an extensive examination of normal time and payment for diagnoses in the inpatient (DRGs) and outpatient (APCs) arenas. CPT codes followed a similar developmental course that focused on medical and surgical procedures. The significant evolution that has occurred since the onset of Medicare has been (1st) payment for services plus capital costs to (2nd) payment for services based on diagnosis to (3rd) payment for service outcomes. Medicare generally pays about 60% of charges. While this is a higher payment than Medicaid, it is still a low payment that places a significant financial strain on hospitals and health systems.

Medicare part B covers outpatient services and was originally targeted as physician office coverage. This coverage is optional for Medicare recipients and comes with a small fee that is automatically deducted from the recipient’s Social Security check. Post DRG implementation (1983) a significant amount of inpatient care has shifted to the outpatient or ambulatory care arena that is now included under part B coverage. Physician payment has developed along a route similar to hospitals with the initial payments being cost plus and then going through a number of legislative iterations that have had limited initial success in reigning in costs as physicians quickly discovered how to profit from the changes. The most recent iteration is the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA – PL 114-10). In MACRA physicians were given two payment options with the first low risk option including all current payment options plus a revised quality outcomes incentive. The second higher risk option is a risk sharing arrangement where physicians can reap considerable profits and, if not managed well, considerable losses.

Medicare part C began as Medicare + Choice (PL 105-33) signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1997. This plan allowed a limited number of Medicare recipients to opt for a commercial managed care plan instead of traditional Medicare. While the plan was successful it was also limited in scope and in the number of Medicare beneficiaries allowed to enroll. Part C was included in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (PL 108-173) that included: changing the name to Medicare Advantage, a guarantee of at least 2 plans per geographic area, managed care plans required to negotiate drug prices and develop a formulary, and significantly increased part A and part B reimbursement payments. As of 2021, 43% of Medicare recipients are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.

Medicare part D is a prescription drug coverage payment option for Medicare recipients addressing the lack of prescription drug coverage and was a part of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 under President George W. Bush. Part D coverage consists of 4 payment stages: out-of-pocket deductible, initial coverage, out-of-pocket coverage gap (called the “donut hole”), and catastrophic coverage. The significant out-of-pocket cost associated with the coverage gap was reduced in the PPACA, and ultimately the gap will be eliminated.

Insurance

Insurance is a tool people use to hedge against the loss of a possession or asset. In the United States, the first insurer was Benjamin Franklin, who was a partner in the Philadelphia Contributorship that sold household fire insurance. Since the founding of the United States, there has been a struggle over whether the regulation of insurance should belong to the states or the federal government. Following a series of legislative attempts and judicial rulings, the issue of regulatory authority was settled by the McCarran-Ferguson Act (15 U.S.C. §§ 1011-1015), in 1945 that gave the states the right and responsibility to regulate insurance. The rationale for the states having regulatory power is their closeness to the citizens and providers of insurance products thus their ability to keep a closer watch on industry activities.

Insurance is based on a large number of individuals pooling their risks and paying (the insured) for an insurer to collect their funds and reimburse them for their loss. There are three salient characteristics embodied in all insurance produces. First, the unlikelihood of everybody in the pool suffering from the same loss at the same time. Second, the greater the size of the pool of insured, the less likely simultaneous will occur resulting a smaller risk and financial exposure. Third, the solvency and ability of the risk contract holder to pay claims. These concepts are known as indemnification, or securing protection against hurt, loss, or damage.

In addition to the above, major concepts shared by all insurance products include moral hazard or the insured taking on more risk than is designed in the risk contract. In healthcare insurance, moral hazard is encountered by individuals who go to the doctor as often as they wish because their visit is “free” of no out-of-pocket cost. A similar concept is adverse selection or when an insured gains coverage below the true cost of their risk. Adverse selection occurs when the insured has knowledge of medical or surgical needs that are not shared with the insurer. For example, when an individual becomes insured just prior to undergoing an expensive medical or surgical procedure. Three other common terms that frequently need clarifying are premium, co-pay, and deductible. A premium is how much an individual or organization pays the insurer for insurance coverage. Premiums are paid on a regular basis with time intervals between payments ranging from annually to monthly. Co-pays are a regular negotiated or stipulated amount individuals pay for each medical or surgical encounter regardless of the total amount of the final bill. Co- pays can range from as low as $5 to $300 per encounter. Deductible is a predetermined amount the insured must pay prior to the insurer paying. In the current environment, deductibles can range from $500 – $8,000.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act took aim at eliminating some specific insurance concepts such as individual versus community rating and guaranteed issue and renewal versus exclusion for preexisting illness and recission. Individual rating is a pre-ACA rating method where insurers would rate the actuarial risk of the contract based on prior performance of the group insured by the contract. In other words, if the group had no significant medical or surgical events during a year, they could anticipate a small to moderate increase in premium cost. However, if one member of the group had a major medical or surgical event such as an expensive cancer treatment regimen or hear surgery, the group would experience a significant premium price increase the following year. The ACA eliminated individual rating and replaced it with community rating. Community rating provides a larger pool of insured individuals thus absorbing significant loss from a small number of members.

The ACA also eliminated recission or the cancellation of an insurance contract because it became too expensive for the insurer and exclusion for preexisting illness again because this situation was deemed too expensive for the insurer. In place of these to practices, the ACA promulgated guaranteed issue which is a practice that states everyone who applies needs to be issued a policy and that policy cannot be rescinded due to excessive costs. These three negative insurance practices were replaced with the practice of everyone being able to gain health insurance and that the way to absorb the increased risk is through a larger pool.

Finally, an insurance practice that emerged as a result of a last- minute provision in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974 is self-insurance. As discussed in the history of insurance, states have the responsibility of regulating and thus can set the criteria or requirements for insurance contracts. As a result, every state has slightly different requirements for health insurance coverage which can be very difficult for firms to manage when they have a presence in several states. Coupled with this, every employer providing health insurance coverage for their employees seeks the best value or the best coverage at the lowest cost. The self- insurance provision in ERISA allowed firms to fund the health insurance needs of their employees through a non-actuarial budget mechanism that allowed them to avoid the varied state requirements since they were not providing insurance rather simply paying for the health care needs of their employees. Normally, firms hire an insurance company to administer the plan while not purchasing an insurance plan for their employees. Self-insurance firms can avoid varied state requirements and provide health coverage at a decreased cost. Firm size is directly correlated to the use of this payment option with over 90% of firms with at least 500 employees using self-insurance as opposed to less than 5% of with 50 or fewer employees choosing this option.

Employer-Sponsored Insurance

The journey to employer sponsored insurance (ESI) in the United States began with the need for medical insurance. While sickness funds worked quite well during the latter half of the 19th century and early years of the 20th century, by the mid-1920s medical sophistication and technological advancements were causing the price of medical services to increase beyond the ability of many to afford them, requiring some type of third-party payment intervention. Even though Western Europe was moving in the direction of centralized provision of social services (German Sickness Funds – 1880s, and English National Health Insurance for workers – 1905), Americans had no appetite for centralized government provision of medical services. Sociologically, this was a result of just winning “the war to end all wars” (WWI) and the resulting bitterness toward anything German and any semblance of socialism after witnessing the atrocities associated with the Bolshevik Revolution (1917).

In 1929, Baylor University Hospital was on the brink of bankruptcy due to unpaid bills with a large portion coming from their university faculty. The hospital recruited a successful sickness fund executive to lead them through this difficult situation. As a result, the hospital developed a pre-paid plan that it offered to its faculty at 50 cents per month or 1% of income (the same pricing as paid for sickness funds). This program became very popular very quickly, expanded very quickly, and allowed Baylor University to move to a solid financial position. This plan was certified by the State of Texas as a nonprofit health insurance plan and ultimately became known as Blue Cross. Ten years later in 1939, a similar set of events occurred in California with a group of physicians organizing a plan eventually becoming known as Blue Shield (Cunningham & Stevens, 1997).

Employers reluctantly recognized that the provision of medical insurance was a mutually beneficial agreement that resulted in fewer worker absences and increased worker productivity. However, it was a set of three events occurring over an 8-year period that solidified the provision of medical (later health) insurance as an employee benefit. First, the high inflation following the end of WWII was addressed by the War Labor Board through wage and price freezes. After employers complained about the inability to attract and retain employees by increasing wages, the War Labor Board authorized the payment of non-cash wages to employees. These non-cash wages became known as employee benefits with the first two benefits being provision of medical insurance (only for the employee) and vacation time. Second, in 1949 the Supreme Court issued a ruling backing a National Labor Relations Board rule allowing benefits to be included in labor negotiations. Third, in 1951 Congress deemed employer paid medical (health) insurance premiums tax deductible.

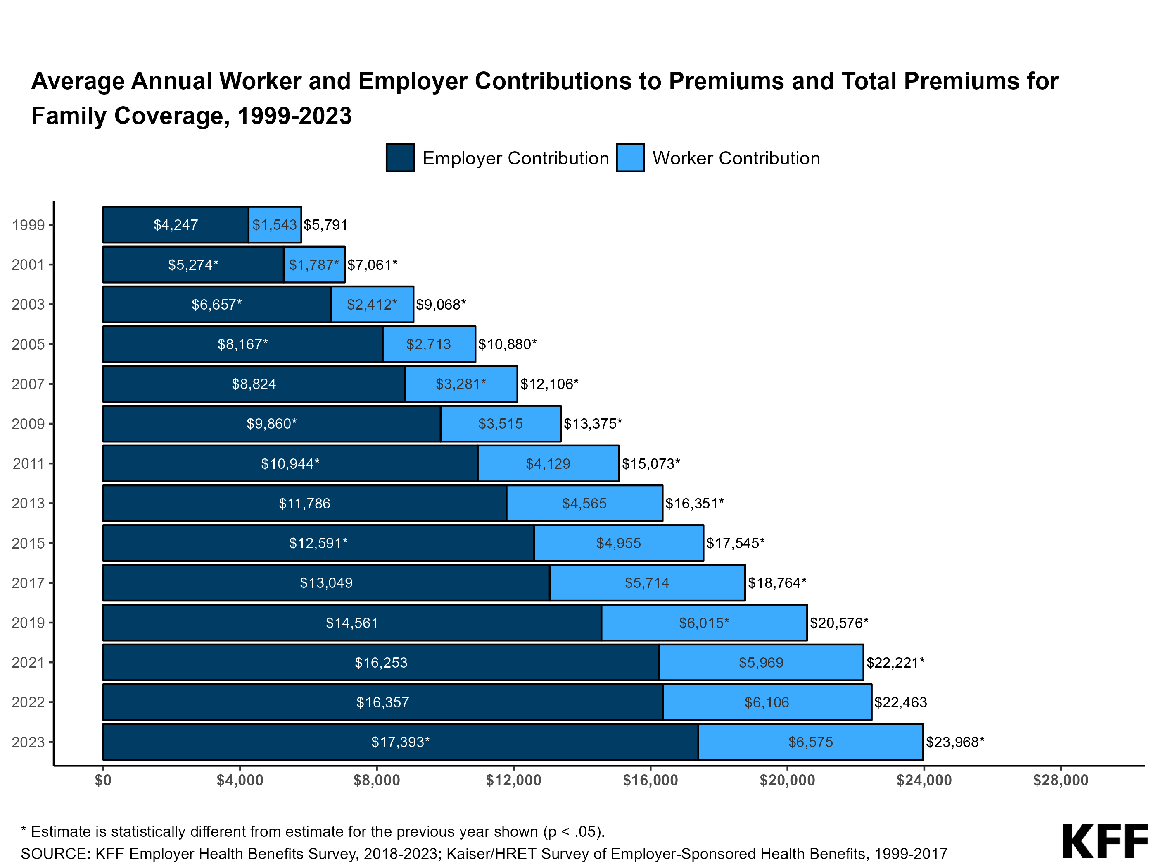

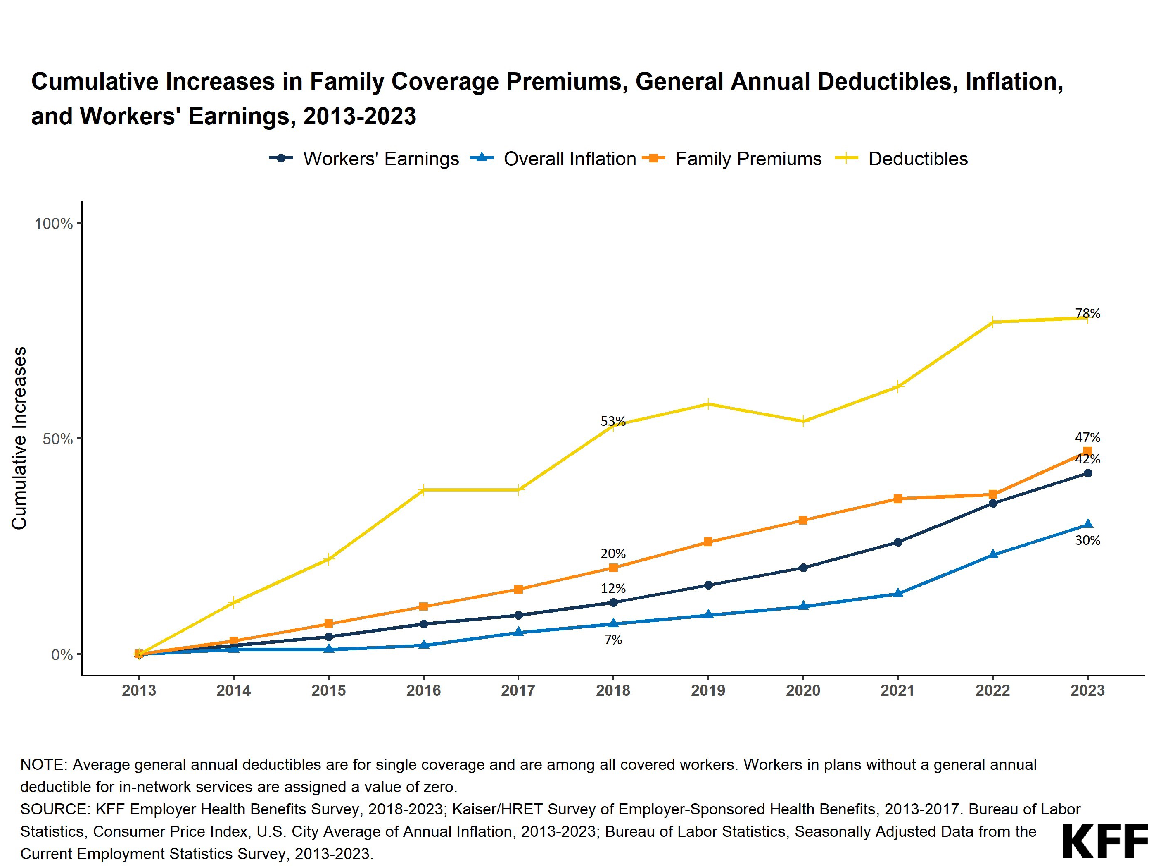

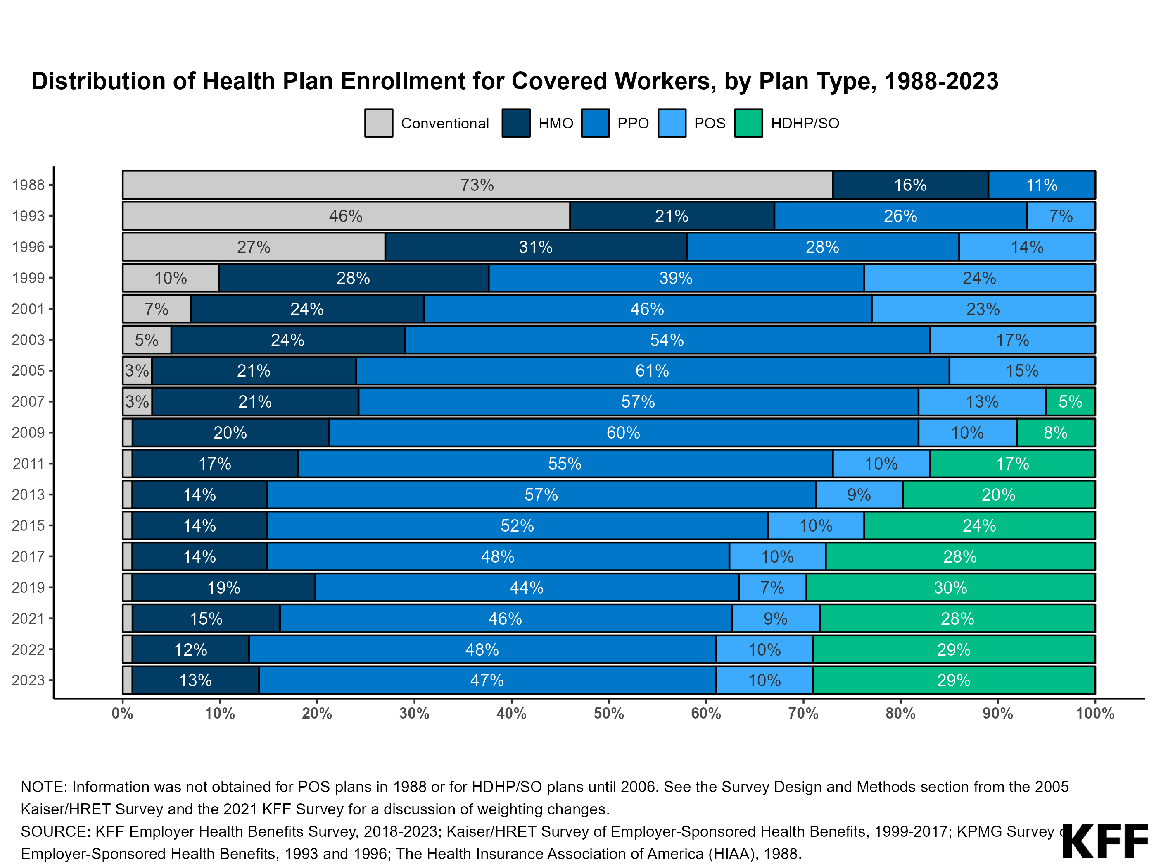

Prior to 2010, the percent of workers receiving employer sponsored insurance ranged from 60%-69% while post-2021 the range has held within the mid-50% range (Figure 1). The employer sponsored insurance journey is similar to that of hospitals and physicians. Initially, medical insurance was what we categorize as catastrophic indemnity insurance with copays ranging from 10%-20%. Catastrophic indemnity insurance pays only for large expenses over a certain amount, such as hospitalization, similar to automobile insurance. Gradually more services were offered as part of medical insurance until any service, including preventive care, might be included in an employer sponsored plan. Initially, medical insurance was only for the employee and not the employee’s family. The growth in family coverage occurred following the 1949 Supreme Court ruling allowing benefits to become a part of labor negotiations and increased the cost of medical insurance to employers. Medical (health) insurance cost escalation occurred in conjunction with the escalating cost of medical care to a point where executives found continued medical insurance price increases unsustainable and began to demand more for their money and from their employees. Executives pursued three lines of action to reduce escalating medical insurance costs. First, in the 1980s they began shifting employer sponsored insurance to managed care plans, which were developed to increase efficiency and cost controls of healthcare by combining financing, insurance, and service provision. Second, in the 1990s employers demanded improved health outcomes, thereby initiating the healthcare quality movement. Third, they began to require their employees pay a portion of the premium and began to insist upon other funding mechanisms such as copays and deductibles (Figure 2). After 1990, managed care plans became the dominant employer sponsored insurance model. Limitations on patient choice in managed care led to a shift towards a hybrid approach and the most popular plan currently is the preferred provider organization (PPO) that has elements of managed care coupled with patient choice. Since 2010, high deductible PPO plans coupled with a health savings account, where employees are responsible for a large deductible before medical services are covered, are on a trajectory to become the most popular plan (Figure 3).

Figure 1

Average Annual Worker and Employer Premium

Published in 2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey – Summary of Findings

Figure 2

Cumulative Increases in Family Coverage Premiums, General Deductibles, Inflation, and Workers Earnings, 2013-2023

Figure 3

Distribution of Health Plan Enrollment for Covered Workers, by Plan Type, 1988-2023

Individual Insurance

The individual insurance market has been around for about as long as the group market and has accounted for about 4% to 6% of the total market. Individuals purchasing medical (health) insurance through the individual market have generally been employed by small employers (fewer than 50 employees) or professionals such as physicians or lawyers in solo or small practices. The PPACA rearranged the individual market providing a federal government sliding scale subsidy for individuals between 100% to 400% of the federal poverty level. Plans purchased through the Marketplace are required to meet the PPACA criteria of a quality plan. Prices for individual plans generally run from $4,000 to $8,500 per year. Despite all of the attention given to this area of the insurance market by elected officials and the media, the total percent of the market has only increased by about 1%.

The Uninsured

Being classified as uninsured is predicated on the desire or need to have insurance. The need for medical (health) insurance is due to the cost of medical care being cost prohibitive for the population without a third-party payment option to protect them from catastrophic financial loss. In the current environment, having medical (health) insurance is an assumed requirement for having access to medical (health) care services or without medical (health) insurance individuals are not guaranteed access to regular medical (health) care services. The uninsured population can be categorized in a couple of different ways.

First, the uninsured can be divided into three groups. About 5% of individuals with significant financial means can easily fund their own medical (health) needs and find the purchase of medical (health) insurance to be of limited to no economic value. The remaining two segments are about evenly divided with one group being the short-term uninsured consisting of individuals who normally have employer sponsored medical (health) insurance but find themselves between jobs. These individuals are normally re-employed and have medical coverage within 6 months yet have the option to purchase COBRA Insurance for coverage during their time out of work. COBRA stands for Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (PL 99-272) and was passed in 1985. As part of the bill employees leaving their jobs must be provided the option to purchase the insurance, they had from their employer for up to 18 months. Those who are disabled may extend coverage to 29 months, and divorcees and widows for the former employee up to 36 months. The challenge with COBRA insurance is that the individual must pay the full premium plus a small administrative fee thus incurring a high additional household const during a time when they are seeking to preserve cash. The final group are those who are chronically uninsured and are characterized as either self-employed or working for small employers who cannot afford to provide medical (health) insurance. A large portion of this group are also characterized as low income and can benefit from the PPACA expanded Medicaid or Insurance Marketplace provisions. These individuals can often benefit from provider charity and discounted payment policies.

Another way to characterize the uninsured is to use the divisions provided by the Kaiser Family Foundation identifying that 20% of the uninsured are ineligible for financial assistance due to affordable employer marketplace coverage, 15% ineligible for coverage due to immigration status 6% are in the PPACA coverage gap, 25% are Medicaid/CHIP eligible, and 35% are tax credit eligible. Stated otherwise, pre-PPACA 18% percent of the population was uninsured, post-PPACA 8.2% are uninsured. If everyone eligible for Medicaid, CHIP, or Marketplace subsidies was enrolled in these programs the uninsured rate would be 2.7% (in 2021) as opposed to 8.9% (KKF, 2024).

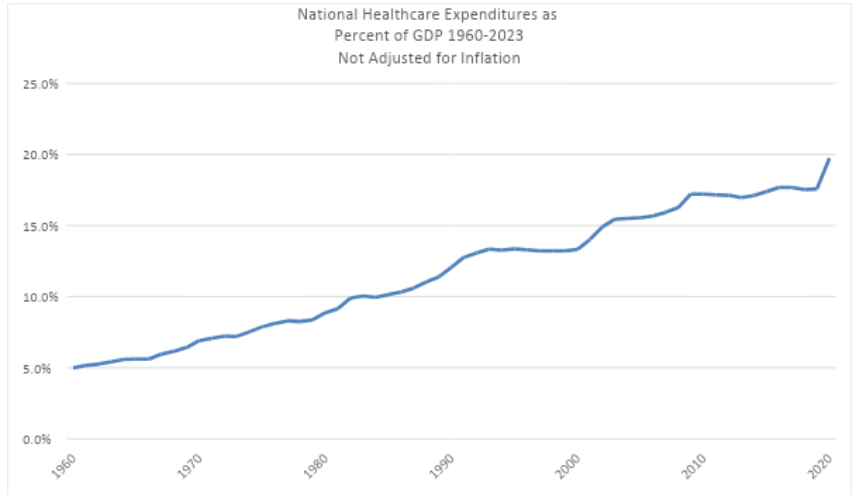

Healthcare Spending Growth

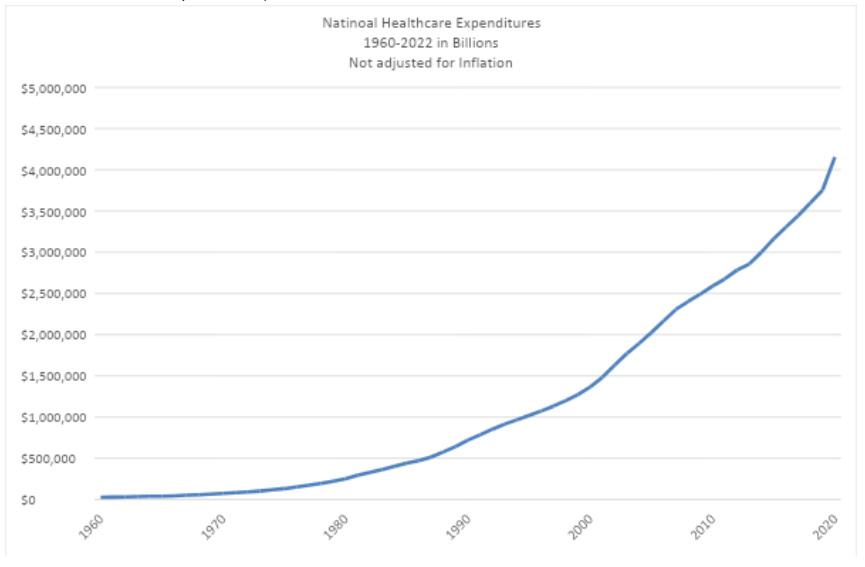

Growth in healthcare cost has increased dramatically since 1960 (see Figure 3 and Figure 4) or just prior to the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. There are several reasons attributed to why spending has increased so dramatically such as inherent inefficiencies (25% – 40%) and technological advances (25% – 35% – Yamamoto, 2013). However, even the casual observer can pick up from the Figures below that those costs have risen both in dollars and as a percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) as consumers have removed themselves from the direct payment for healthcare services and relied on a third party to pay the bill. From a behavioral economics view, consumers have lost their cost sensitivity thus, many remedies to this problem over at least the last 20 years have been to increase consumer cost sensitivity through co- pays, deductibles, and by directly paying for a higher portion of their health insurance premium (frequently as part their employer sponsored insurance).

Figure 3

US National Health Expenditures, 1960-2020

National Health Expenditure Data: https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/historical

Figure 4

National Health Expenditures as a Percent of GDP

National Health Expenditure Data: https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/historical & https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/USA/united-states/gdp-gross-domestic-product

Payment Methods

There are only two basic payment methods that can be used to pay for any purchase of goods or services. First, an individual can pay after receiving goods or services, which is the basis of how most of us conduct the majority of our business. This is known as the fee-for-service (goods) model. Second, an individual can pay for a purchase prior to receiving the service or good. This second method is often used with insurance and is called a prepaid plan. While each of these payment models have numerous variations of the basic payment model, they each have distinctive incentives associated with both the payor and payee that, when taken to an extreme, prove untenable and unsustainable. From a medical provider lens, fee-for-service encourages volume – the more you produce, the more you get paid. The negative incentive associated with volume is to skimp on quality to produce a greater quantity. On the other hand, prepaid plans can negatively incentivize providers to provide fewer services in order to claim a higher profit. The incentives for payees or consumers are just the opposite with fee-for-service incenting use or purchase only when necessary due to the individual cost; whereas, with prepaid plans there is normally no payment at the time of service creating a consumer incentive to use or purchase as often as desired since the cost appears to be free.

Fee-for-Service

Fee-for-service is the economic model most individuals follow for almost all of their personal and professional business activities. Simply stated, we need a service, seek a service provider who provides the service, and pay for the service once provided. This is the method we use when grocery shopping (purchase of goods), eating at a restaurant (purchase of services). In healthcare whether an individual needs services provided by a facility such as a hospital, physician, or some other healthcare professional, we seek the service, receive the service, and pay the bill. Despite a lot of current efforts to shift payments to risk-based and outcomes-based models, the majority of today’s payment models are some variations of fee- for-service.

All fee-for-service models require patient encounters and interventions to be billed by codes supported by provider and allied health documentation. The more complexity, risk, skill, or time required for the encounter or intervention, the higher the code level and higher the charge. Another commonality with fee-for-service charging and payment is the contract that the third-party payer holds with the provider. Common features of fee-for-service contracts include either a preestablished fee schedule that providers accept as part of the contractual agreement or a negotiated discount on the charges submitted by providers. In the end, it is a rare occasion when any payer pays full charges. Even in the current environment with risk-based and outcomes-based contracts, providers are paid on a fee-for-service basis or after the service has been provided.

Prepaid Plans

Prepaid plans refer to any payment arrangement where payment is made prior to receiving services. One version of a prepaid plan is any medical service that is seen as free. As in the early days of manufacturing, many large employers have on site health clinics that come at no cost to those using the clinic services. Another version of this are the provisions in health insurance packages such as annual physicals or other preventative health measures that consumers view as free. None of these above activities are actually free, rather the cost for them is covered by the employer or built into the health insurance premium.

Capitation is the best-known prepaid plan in healthcare and is a unique payment arrangement found most frequently in managed care types of policies. The salient feature of capitation includes payment ahead of time or before services are provided with the underlying premise that the provider will work diligently to manage the patient’s care to prevent serious illness that is expensive to treat. Capitation creates some financial risk for the provider: if a patient requires more treatments than are paid for in the capitated rate, the provider assumes those costs as a loss. Thus, it is in the provider’s best interest to keep the patient as healthy as possible, keep all chronic diseases well managed and controlled, and avoid expensive hospitalizations or diagnostic tests. There is an evolving trend to move some risk-based contracts from fee-for-service to capitation; however, this movement is in its infancy. Most frequently, capitated contracts are made with large healthcare organizations or physician groups (independent physician groups, independent physicians organized by physician organizations or physician-hospital organizations), or through integrated healthcare delivery systems. When these groups negotiate contracts, they normally negotiate a capitated rate for primary care physicians with a fee-for-service provision for specialists and surgeons.

Managed care

Managed care comes in a variety of forms with all of them seeking to control costs through the proactive management of patient health. The underlying premise of managed care assumes that when care is delivered as preventative and early, patients can avoid (or significantly delay) severe illness and large medical bills. The most restrictive model of managed care is the staff model where the managed care company owns all the treatment facilities and employs all the clinical providers and allied medical staff. In this model, all care is required to be delivered in and through the managed care organization. Following close behind this model are Health Maintenance Organizations (known as HMOs) that require patients to use a narrow panel of providers and get pre-authorizations for any potentially expensive treatment or diagnostic procedure. While these first two have the best ability to control costs, the restrictions led to employee and patient complaints. The most common managed care model today is the Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) which requires patients to use in-network providers or pay a higher co-pay if they want to access an out-of-network provider who does not have a contract to be included in the PPO’s provider panel. The common theme in all of these variations of managed care are deep discounts on policy premiums traded for narrow provider networks ensuring increased volumes of patients and a focus on keeping patients as healthy as possible, avoiding severe illness. Managed care models can be developed as either capitated or fee-for-service payment models with the more restrictive models most commonly being capitated and the less restrictive fee-for-service.

Value-based care

Value-based care had its beginnings in the 1990s with the advent of the quality movement in healthcare. Large employers were the first group to bring quality of healthcare services to the forefront due to what they perceived to be continually increasing health insurance premiums coupled with decreasing quality of care. The federal government quickly followed suit by including quality measures as part of Medicare, Medicaid, and other government payment programs, and commercial payers adapted the federal program approaches. In the early days of healthcare quality initiatives, providers would receive payment incentives for meeting predetermined quality measures but received no penalties for not achieving these measures. In other words, this arrangement created one-sided risk (the risk of losing a premium payment) due to not achieving quality metrics but had no other penalty for not achieving them.

In an attempt to address these less than stellar results of the above quality measures, the federal government during the George W. Bush administration conducted a number of payment experiments through the Medicaid 1115 waiver program. These experiments proved very successful at controlling the increasing cost of care while increasing the quality of patient outcomes. As a result of the success of these programs, they were all included in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in the CMS Innovation Center. One of the major concepts emanating from these experiments was value-based care.

Value-based care is the name given to the Medicare program that is revenue neutral (or does not expend any additional funds) and only allowed providers to recoup their withheld funds if they met preestablished thresholds. These thresholds include requirements such as specified levels of patient satisfaction and quality measures associated with selected, expensive chronic conditions. Providers could receive a premium for exceeding their quality measure thresholds. As this program has evolved and matured, the patient satisfaction portion of the criteria has remained unchanged while the number of diseases and cost control measures have increased. The revenue neutral nature of this program is an initial movement toward two-sided risk for providers where providers must focus on quality and costs or face the prospect of reduced income through a lower reimbursement as well as not receiving the increased income from the value-based premium. This concept of value was carried over into a couple other programs in the CMS Innovation Center. Shortly following the introduction of the value-based care program described above, Medicare introduced a series of payment programs that did not pay providers if a Medicare patient was readmitted for any reason within 30 days of the initial encounter. Medicare later expanded the list of illnesses on the no re-admit list and expanded the program to include 60 days and 90 days readmissions. The premise behind this program is that providers are responsible for patient outcomes after they leave the facility and that patients are readmitted due to health services fragmentation or a lack of coordination of care. Thus, if providers could not get a patient’s care coordinated, they were also not going to get paid for any care beyond the defined time window if the patient had to return for further treatment. The risk associated with this model was negative risk or a penalty of not receiving payment if care was not coordinated and required additional admission(s) due to lack of coordination of care.

The highest level of risk in the value models is the Accountable Care Organization (ACO). In these organizations, one or more providers are assigned a panel of patients and are required to actively manage their care to meet the organization’s specific quality or patient outcomes thresholds. If they meet the thresholds, they will receive a premium of 2% to 4%; however, if they do not meet the threshold, they risk losing an equal amount. The initial ACOs included only one-sided risk where providers could earn a premium but would not lose any money. As this model has matured, it has shifted to two-sided risk where providers also will lose money if thresholds are not met. The most current data for FY 2020 indicates that ACOs earned $2.3 billion in performance premiums while saving $1.9 billion.

Provider Payment

Providers include institutions where services are delivered as well as the professionals who delivery services. Under the fee- for-service model, providers are paid differently based upon the location of the services delivered, complexity and skill level associated with the services provided, and the level of risk associated with providing the services. Regardless of whether an institution or clinical professional is billing for services, all billed services must be supported by documentation indicating the need for services, services provided, and patient outcomes. Once the documentation is completed, all providers bill by submitting a code for services valued at a predetermined monetary amount. Under prepaid service models, providers are paid a predetermined amount to keep their patients or residents healthy and intervene early when acute illnesses occur in an effort to limit their cost exposure.

Physicians

Physician payment has evolved through a number of iterations in attempts to accurately capture the complexity of skill, training, and risk associated with delivery of services. While these payment models have sought to pay physicians fairly, they have also sought to limit excessive physician payment. The current payment model, MACRA (the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 – PL 114-10) was signed into law in 2015 as the “permanent doc fix” designed to address a number of concerns regarding equitability of payment and correcting for the historic underpayment for cognitive services as opposed to procedural services. MACRA provided two options for physician payment: the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and Advanced Payment Models (APMs). MIPS combined three existing quality-focused payment systems into one system. MIPS was an attempt at administrative simplification that allows physicians to earn incentive payments for meeting predetermined quality measures and is the model recommended by CMS for most physicians. APMs payment models that provide physicians the opportunity to earn higher incentive payments by taking on predetermined levels of payment risk. The risk aspect of these payments can award physicians substantial incentive payments if predetermined quality and outcome measures are met. In contrast, physicians can incur substantial loss by not meeting these measures. While MACRA is a payment model for governmental programs, most commercial and non-profit payers adapt governmental payment models and implement their own versions.

Allied Health Providers

Allied health providers are a group of non-physician professionals who can bill for services and include professionals such as advance practice nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech therapists. The allied healthcare professionals provide specific diagnostic and therapeutic services limited to the scope of their professional training. Their billing models are similar to physician fee-for-service models although at a much lower payment rate. Almost all of these professionals have the ability to provide and bill for a limited amount of initial treatment without a physician’s order. However, extensive treatment plans need to be approved and authorized by a physician.

Facility Payment

Facility payments are provided for the places where services are delivered or organizations that deliver those services. Health systems and hospitals are the largest facilities that bill for services and are the organizations that receive the largest payments. The rationale for the higher payment is similar to the rationale for physician payment, with health systems and hospitals providing the most complex care requiring the highest skill mix and greatest level of risk. As with provider payment, fee-for-service billing is based upon documentation and submitted to payers as billing codes.

Other organizations that bill include, but are not limited to, physician offices, outpatient clinics, outpatient surgery centers, nursing homes, and other continuing care providers such as home care and hospice care providers. These types of providers receive a lower payment than health systems and hospitals due to the lower complexity of care, skill mix, and risk.

Pharmaceuticals and Durable Medical Equipment

Pharmaceuticals are normally billed and paid separately by most payers with the two exceptions being inpatient hospital care and residential skilled nursing home care. Many payers structure pharmaceutical payments through at least a defined formulary of the drugs they will pay for and frequently through a pharmacy benefit manager that negotiates with pharmaceutical companies for lower prices due to volume purchasing and the use of generic substitutes to brand name drugs. Durable medical equipment payment is similar to pharmaceuticals with the payer requiring the provider document the need for the equipment. Durable medical equipment includes devices designed for long-term use such as orthopedic support devices, blood sugar measurement and tracking devices, hospital beds, and oxygen equipment, among others.

Basic Science Research Funding

The majority of basic science research that leads to improved understanding of diseases and treatment of diseases occurs either at or through funding provided by the National Institutes of Health. Annually this funding is in the $40 billion range with most of it spent through grants to universities where the research is conducted. Once the basic research is completed or at a point where the findings are clinically applicable, commercial researchers such as pharmaceutical companies secure the basic science findings and further develop them into commercial products.

Summary

Funding of healthcare services in the United States has evolved over time from an arrangement between patients and physicians to a mixed public/private system where hardly any end users of services make direct payments to providers for the full amount charged for those services. All providers document the services provided that are then paid by a third-party payer. Hardly anyone receiving those services understands the true cost of health care in the United States, nor do they understand

how much or why providers are paid what they are paid. The driver of payment reforms in the US is the federal government with commercial and nonprofit payers normally following the federal government’s lead when creating their own payment systems. Finally, the high rate of health care spending increase, while caused by a number of factors, is broadly considered a problem of the lack of health care cost and payment salience by those delivering and receiving services due to the third-party payment system providing a wall of sorts between them.

Key Words

Barter: Bartering is the oldest form of purchase and trade, where items or services are traded without the need for currency.

Sickness funds: A means used for employers to support employees who would lose income due to illness or injury prior to the availability of medical insurance.

Blue Cross: The nonprofit insurance organization developed to create hospital plans.

Blue Shield: The nonprofit insurance organization developed to create physician services coverage.

Fee-for-service: The model by which providers are paid based on services provided.

Diagnosis related groups (DRGs): An early cost-control measure that set payment rates for providers based on patient diagnoses and severity.

Capitation: A prepaid payment model which covers all necessary services for a given time.

Value-based payment: An effort to shift payment from reimbursing for services to paying for outcomes that requires providers meet specified patient satisfaction and quality of care thresholds.

Managed care: An insurance model that packages insurance, care provision, and payment into one organization.

Medicaid 1115 waiver program: A program that allows CMS to work with states to develop innovative pilot programs designed to address identified problems or desired improvements.

Preferred Provider Organization: A less restrictive managed care model that has a broader physician network and allows patients to access out-of-network providers.

Accountable Care Organization: An organization of one or more providers that agree to increase care coordination for complex patients in order to improve health outcomes and reduce costs.

MACRA: A federal law enacted to reduce costs by sharing risk with providers and increase quality of care.

MIPS: A MACRA physician payment model that provides payment premiums and penalties for meeting or missing quality thresholds.

APM: A MACRA physician payment model that has increased potential for income or loss based on providing high-quality care and cost-efficient care.

References

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021). Affordable Care Act’s Shared Savings Program Continues to Improve Quality of Care While Saving Medicare Money During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press- releases/affordable-care-acts-shared-savings-program- continues-improve-quality-care-while-saving-medicare

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020). National Healthcare Expenditures.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2024). https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2023-shared-savings-program-fast-facts.pdf

Cunningham, R. M. & Stevens, R. A. (1997). The Blues: A History of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield System. Northern Illinois University Press

History Page. (n.d.). Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service. Retrieved March 22, 2022, from https://www.usphs.gov/history

“If You Knew the Conditions…” Health Care to Native Americans: Early United States Government Interest in Native American Health. (n.d.). [Exhibitions]. U.S. National Library ofMedicine.RetrievedMarch22,2022,from https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/if_you_knew/ ifyouknew_03.html

Kaiser Family Foundation, (2021). Analysis of Medicaid eligibility and current population survey.

Leonard, T.C. (2016). Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era. Princeton University Press

Medicaid. (nd). Program History. https://www.medicaid.gov/ about-us/program-history/index.html

Murray, J.E. (2007) The Origins of American Health Insurance: A History of Industrial Sickness Funds. Yale Press

Yamamoto, D. H., Health Care Costs—From Birth to Death (2013). Sponsored by Society of Actuaries, Part of the Health Care Cost Institute’s Independent Report Series – Report 2013-1