17

Healthcare: A Global Perspective

Joni Roberts, DrPH, CHES

California Polytechnic State University

Sandra Banjoko, PhD

La Sierra University

Dilys Brooks, PhD

Loma Linda University

There is no one size that fits all. We must work country by country, region by region, community by community, to ensure the diversity of needs are addressed to support each reality. – Amina J. Mohammed, Deputy Secretary-General, UN

Learning Objectives

- Identify the four main healthcare system models outside of the United States.

- Understand the forms of healthcare finance and insurance in other parts of the world.

- Learn about other non-traditional and collaborative forms of healthcare systems.

- Summarize the pros and cons of each healthcare insurance system.

Introduction

When comparing healthcare systems globally, it quickly becomes evident that arrangements are different for every country based on its gross national income, type of government, available resources, and population needs. Nevertheless, a closer look across these diverse systems reveals four predominant models for healthcare delivery.

In addition to these healthcare models, a variety of health insurance plans have been developed to meet the healthcare needs of citizens (and, in some places, permanent residents). However, there is a broad discrepancy between what is available and affordable for people living in The United Nations categorizes countries into these four main classes based on gross national income per capita. Some High-income Country (HIC) and Upper-Middle Income Country (UMIC)s have established healthcare delivery systems readily available to their citizens, but in several Lower-Middle Income Country (LMIC)s, accessible healthcare is not readily attainable without incurring financial hardship.

The Major Models of Healthcare Systems

Four healthcare system models predominate across the globe: the single-payer national health service (The Beveridge Model), the social health insurance model (The Bismarck Model), the market-driven healthcare model, and the national health insurance model (Chung, 2017). Each model is described in detail below.

Single-payer National Health Service

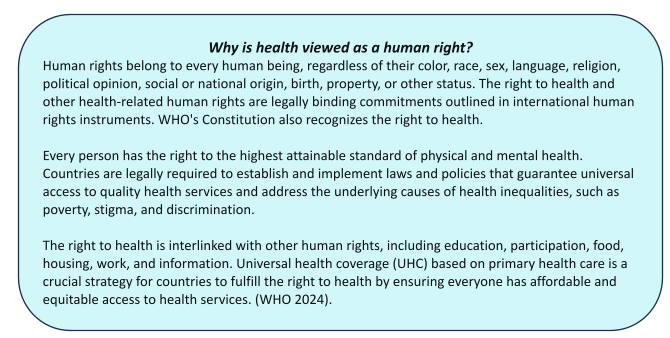

In single-payer national health services, the government acts as the single-payer of health services. Funding for this program occurs through income taxes, allowing care to be accessible at the point-of-service “free of charge” by users. Under this system, most healthcare staff (personnel) are government employees. Unlike other models, a vital component of the single-payer national health services model is that health is viewed as a human right. Therefore, the government guarantees universal health coverage (UHC) for all citizens. This approach is found in countries like Spain, New Zealand, and Cuba and mirrors the US’s Veterans’ health administration system (Light, 2003).

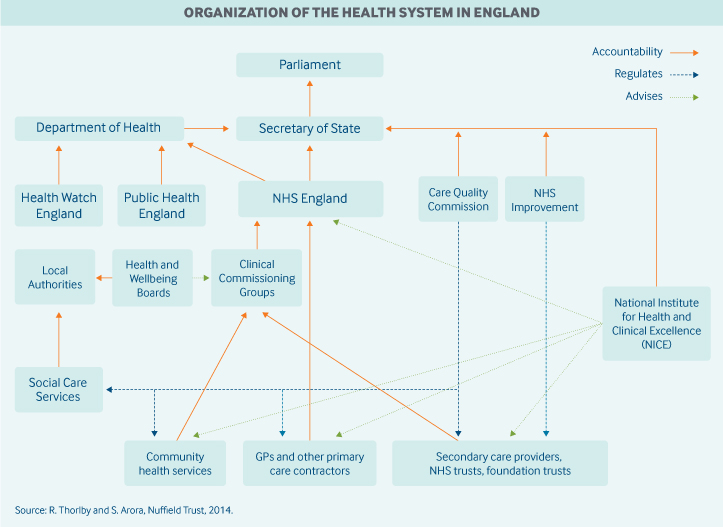

The most famous version of this model is England’s National Health Service (NHS). The NHS was established in 1948 based on the recommendations of a report by Sir William Beveridge, which outlined free health care as a welfare method to eliminate poverty, illness, unemployment and improve education. Each member country of the UK has its version of NHS that oversees health care (NHS England, NHS Scotland, NHS Wales, and Health and Social Care in Northern Ireland) (Thorlby, 2020). For example, NHS England is a large entity divided into various organizations that work at a local and national level. These include the Department of Health, Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships, integrated care systems, clinical commissioning groups, primary, secondary, and tertiary care, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and The Care Quality Commission. While the Department of Health is one of the organizations within the NHS, it cannot interfere directly with NHS decisions. It is responsible for ensuring an effective CCG system (Clinical commissioning groups) and must provide support for commissioning. See Figure 1 for more information on the organization of the NHS in England (Thorlby & Arora, 2018).

Figure 1

Organization of the Health System in England

Knowledge Check

What is the primary source of funding for healthcare services in the Single-payer National Health Service model?

- Self-pay

- Income taxes

- Grants

- Partial (50% self-pay, 50% income taxes

Which country’s healthcare system is most notably associated with the Single-payer National Health Service model?

- Canada

- United Kingdom

- France

- Australia

Answer A: The Single-payer National Health Service model is a healthcare system that provides all citizens free access to medical services at the point of service, regardless of their ability to pay. The main funding source for this model is income taxes, which ensures universal health coverage for all citizens. This approach aligns with the belief that health is a fundamental human right.

Answer B: The United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) is a well-known example of the Single-payer National Health Service model. The NHS was established in 1948 and embodies the principles of universal healthcare coverage and government-funded services that are accessible to all citizens. It provides a comprehensive range of health services, including primary, hospital, and specialist care.

The Social Health Insurance Model

The Social Health Insurance (SHI) model utilized in Germany, Belgium, Japan, and Switzerland is a more decentralized form of healthcare where employers and employees fund health insurance. Employees have access to “sickness funds” financed by compulsory payroll deductions. In addition, private insurance plans cover every employed person, regardless of pre-existing conditions. Although healthcare providers are situated within private institutions, SHI funds are considered public. The administration of this model varies by country: in France and Korea, there is a single insurer; Japan has numerous non-competing insurers, while in the Czech Republic, there are multiple competing insurers. The Social Health Insurance model combines some aspects of Medicaid from the US healthcare system with employer-based health care plans. Regardless of the number of insurers, the government controls prices that limit insurers’ profit-making. These measures allow the government to exercise a similar amount of control over prices for health services as the single-payer national health service model.

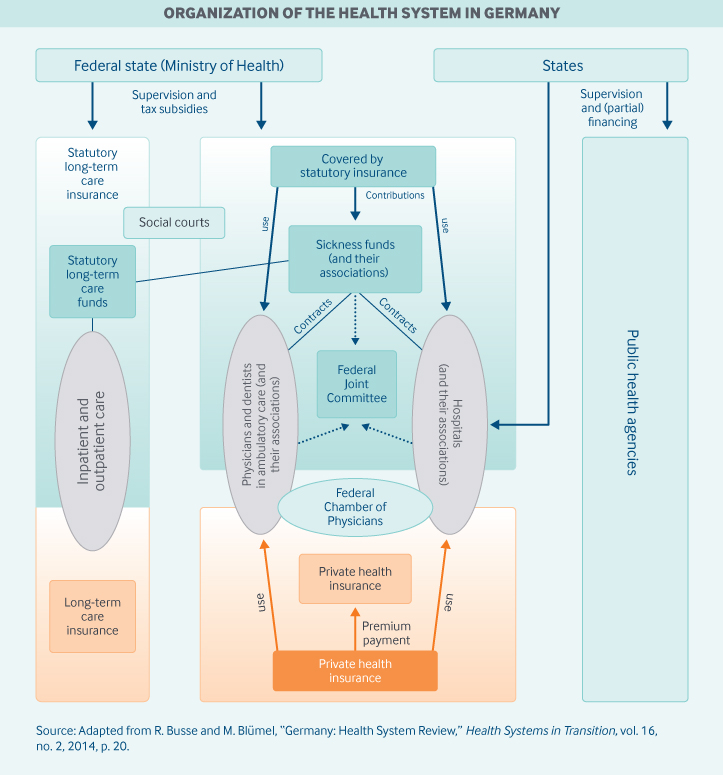

One of the earliest SHI models originated in Germany and is considered the prototype of this healthcare system (Busse et al., 2017). A unique feature of Germany’s design is that while mandating coverage for citizens and permanent residents, the government plays no role in the direct financing or delivery of healthcare. Self-governing associations of sickness funds and provider associations constitute the most important organizational bodies. The Federal Joint Committee manages the delivery system and distribution of funds (see Figure 2). This social insurance model covers a wide range of services, including preventive services, inpatient and outpatient hospital care, physician services, mental health care, dental care, optometry, physical therapy, prescription drugs, medical aids, rehabilitation, hospice, and palliative care, and sick leave compensation (Mossialos et al., 2016). About 88% of the population receives primary coverage through sickness funds and the remainder through private insurance (Busse et al., 2017). Individuals have a free choice of going to a general provider or specialist and are not required to register or receive a referral for the latter.

Figure 2

Organization of Health Systems in Germany

Knowledge Check

How does the Social Health Insurance (SHI) model in Germany differ from that in Japan?

- In Germany, healthcare funding primarily relies on government taxation, while in Japan, it’s funded through compulsory payroll deductions.

- In Germany, the SHI model works through self-governing associations of sickness funds and provider associations, while in Japan, it has many non-competing insurers with a more centralized approach to administration.

- In Germany, healthcare services are provided by private insurance companies, whereas in Japan, they are provided by government-run hospitals.

- In Germany, healthcare coverage is limited to employed individuals, while in Japan, it extends to all citizens regardless of employment status.

Answer – The Social Health Insurance (SHI) model in Germany and Japan have differences in their organization and administration. In Germany, the SHI model works through self-governing associations of sickness funds and provider associations. The government doesn’t have a significant role in financing or delivering healthcare directly. On the other hand, Japan’s SHI model has many non-competing insurers, with a more centralized approach to administration.

The Market-Driven Healthcare Model

Globally, private healthcare systems often supplement national or universal health care models that HIC and UMIC governments provide. Still, sometimes private healthcare systems are the only option for healthcare in LMICs. Underdeveloped rural areas, poor urban slums, and too few resources to support a complex healthcare system, LMICs with this model require patients to pay out-of-pocket for procedures – with many being too poor to afford healthcare at all. Disparities in wealth lead to inequalities in health outcomes in countries with this model, predominantly found on the continents of Asia, Africa, and South America. For example, 42% of South Africa’s total health expenditure is on voluntary private health insurance (PHI), covering only 16% of its population. The market-driven health care model is what many uninsured or underinsured people rely on in the US.

India’s market-driven healthcare model reflects many of the tensions noted above. In principle, all citizens have universal health services available under the tax-financed public system (Mukhopadhyay & Sinha, 2019), with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, state governments, and municipal and local level bodies serving as the public actors in the Indian healthcare system. However, the healthcare sector receives only a small percentage of the country’s national budget, and difficulties accessing government healthcare services compel households to seek private care, often resulting in high out-of-pocket (OOP) payments (Mossialos et al., 2016). In 2017–2018 only around 37 percent of the population had health coverage (Gupta, 2020). Despite the inherent financial risks due to the poor healthcare infrastructure in rural areas and low insurance awareness, increasing purchasing power, rising rates of chronic disease, and growing demand for healthcare have made India attractive to private health insurers. The primary market targeted by the profit-oriented PHIs is the middle-class, further contributing to health disparities and rising costs for the poor. Since most health insurance providers only cover hospitalization expenses, those relying on PHI also have OOP for doctor’s consultation fees, health check-ups, pharmacy bills, dental treatment, and diagnostic tests (Chowdhury et al., 2018).

The National Health Insurance Model

The National Health Insurance model (NHI) incorporates aspects of the single-payer national health service and the social health insurance models. Like the single-payer national health service model, the government is the single-payer for medical procedures. However, like the social health insurance model, providers are private. Universal insurance does not make a profit or deny claims. In some countries like Canada, private insurance contracting is permitted for those who prefer PHI. The balance between public insurance and private practice allows hospitals to maintain independence while reducing internal complications with insurance policies. Financial barriers to treatment are generally low, and patients can usually choose their healthcare providers. Countries that use this model include Hungary, Taiwan, and South Korea. In the US, the Medicare model is similar to the NHI.

Canada has a classic NHI system. It is a decentralized, universal, publicly funded health system called Canadian Medicare. Similar to the NHS in the UK, health care is financed and administered by the country’s 13 provinces and territories. Each has its insurance plan, and each receives cash assistance from the federal government on a per-capita basis. Benefits and delivery approaches vary. However, all citizens and permanent residents receive medically necessary hospital and physician services free at the point of use. Provinces and territories provide some coverage for targeted groups to pay for excluded services, including outpatient prescription drugs and dental care. In addition, about two-thirds of Canadians have private insurance. Private insurance covers services excluded under universal health coverage, such as vision and dental care, outpatient prescription drugs, rehabilitation services, and private hospital rooms (Canadian Life & Health Insurance Association, 2021).

Knowledge Check

Question: How does Canada’s healthcare system exemplify the National Health Insurance (NHI) model?

- Complete privatization of healthcare services.

- Public funding of healthcare by the government while healthcare providers operate in the private sector.

- Government control over both funding and delivery of healthcare services.

- Sole reliance on out-of-pocket payments for healthcare.

Answer – Canada’s healthcare system, Canadian Medicare, is a prime illustration of the National Health Insurance (NHI) model. This model is characterized by public funding of healthcare by the government, while healthcare providers continue to operate in the private sector. In this way, the government serves as the sole payer for medically necessary hospital and physician services, providing universal coverage to all citizens and permanent residents. Meanwhile, hospitals and physicians maintain their independence as private entities.

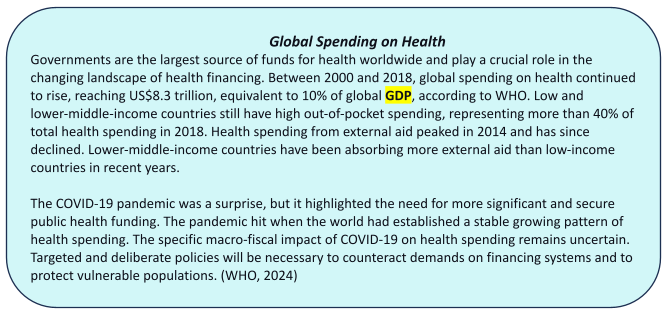

Healthcare Financing

In some HICs, healthcare is financed through general tax reserves, mandatory payments into a government-run social security system, or types of compulsory contributions. For example, Sweden offers healthcare through a national health care system. This system is financed by the general tax revenue raised by city councils and the national tax revenue. This plan is regulated and supervised by the local municipalities with supplemental funding from the national government. The city councils are responsible for most of the financing, purchasing, and provision of resources, sometimes combined with private insurance. About 10% of the employed population (ages 15-74) gets supplementary coverage from employers for quicker access to specialists, medication, and elective treatment. However, some cost-sharing exemptions exist for children, adolescents, pregnant women, and the elderly (Mossialos et al., 2016).

For most UMICs, the government pays some health costs, with the remaining services (e.g., dental, vision, mental health, or prescription medication) covered by OOP payments. For example, in the Republic of China, healthcare is financed through urban employer-based insurance (dependent on the employer and employee payroll taxes) and residency-based basic medical insurance (using individual premiums, funded mainly by central and local government subsidies). In 2018, the central and local governments financed 28% of their healthcare, 44% by public-funded health insurance, private or social health donations, and 28% paid for out-of-pocket. When it comes to out-of-pocket spending, inpatient and outpatient care, including cancer screening and prescription drugs, are subject to different deductibles, copayments, and reimbursement ceilings depending on the insurance plan, region, and type of hospital (community, secondary, or tertiary). Other factors such as physicians’ expertise and type of hospital also play a role in the cost of out-of-pocket spending (Mossialos et al., 2016).

In most LMICs, healthcare is typically funded by the domestic government, international aid, or donors, but many people in such countries are forced to utilize OOP payments to receive treatment. For example, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa witnessed a move towards developing and creating free healthcare in rural areas after gaining independence. As countries began to evolve under government control, government-financed healthcare started to decline in quality of care, with deteriorating infrastructure and highly qualified staff members (e.g., doctors, nurses, physical therapists) leaving the country for better pay and working conditions. Most sub-Saharan African countries have less than one health worker per 1000 population, compared to 10 per 1000 in Europe; see Maphumulo & Bhengu, 2019. Many sub-Saharan African countries receive international support to compensate for the shortfall of personnel. Still, they are directed to use the funds to meet high-priority global health goals, such as maternity care, pediatric services, and diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS (Skolnik, 2021). The World Health Organization considers the minimum amount for primary health care to be approximately $34-40, which few countries in this region can afford to spend per person. As a result, despite widespread poverty, an astonishing 50 percent of the region’s health expenditure is financed by OOP payments from individuals (International Finance Corporation, 2016).

Knowledge Check

What are the primary sources of healthcare financing in Sweden, and how is the system structured?

- General tax revenue raised by city councils and national tax revenue.

- Private insurance premiums paid by individuals.

- Charitable donations from corporations and individuals.

- Sales tax on healthcare goods and services.

How does China finance its healthcare system, and what are the key components of its funding sources?

- Payroll taxes solely funded by urban employers.

- A combination of urban employer-based insurance and residency-based basic medical insurance.

- Donations from international organizations.

- Direct funding from the World Health Organization

What are the major challenges faced by healthcare financing in Sub-Saharan Africa, and how do countries in the region manage their healthcare funding?

- Sole reliance on out-of-pocket payments by individuals.

- A combination of domestic government funding, international aid, and donor contributions.

- Privatization of healthcare services to increase revenue.

- Borrowing from international financial institutions

Answers:

A. Healthcare in Sweden is primarily funded through general tax revenue raised by city councils and national tax revenue. The system is regulated and supervised by local municipalities, with supplemental funding from the national government. City councils are responsible for financing, purchasing, and resource provision, sometimes supplemented by private insurance. Approximately 10% of the employed population receives supplementary coverage from employers for quicker access to specialized care and medications.

B. In China, healthcare is financed through a combination of urban employer-based insurance and residency-based basic medical insurance. Urban employer-based insurance is dependent on employer and employee payroll taxes, while residency-based insurance is funded by individual premiums, mainly subsidized by central and local governments. A significant portion of healthcare costs is also covered by out-of-pocket expenses.

B. In Sub-Saharan Africa, healthcare financing primarily relies on domestic government funding, international aid, and donor contributions. However, despite efforts to develop free healthcare services in rural areas, many individuals still resort to out-of-pocket payments for treatment. Challenges include inadequate healthcare infrastructure, a shortage of qualified healthcare personnel, and limited financial resources, leading to reliance on international support for essential health services.

Other Types of Healthcare Systems

The high ill-health burden, low public spending on health care, high spending on private health care, and partial coverage provided by existing health insurance schemes all point to a crisis in healthcare. The World Health Organization (WHO) has set a goal of reaching UHC by 2030, which would benefit 1 billion people through access to health services and information as a fundamental human right (WHO, 2021). On the one hand, that goal seems presently unreachable due to the proliferation of PHI. Countries like India have seen the health insurance business grow by 25% in just the last few years – despite PHI facing increasing criticism for the lack of regulation of its benefit packages, inadequate risk‐selection procedures, and failure to protect customers (Gambhir et al., 2019). At the same time, models designed to ensure universal coverage in LMICs like Nigeria have failed as well, with only 1.95 health workers per 1000 population and the percentage of Nigerians covered by the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) a paltry 3% (da Lilly-Tariah & Sule, 2020). The many varied crises facing healthcare worldwide have led many countries and researchers to explore alternative models for delivery and financing.

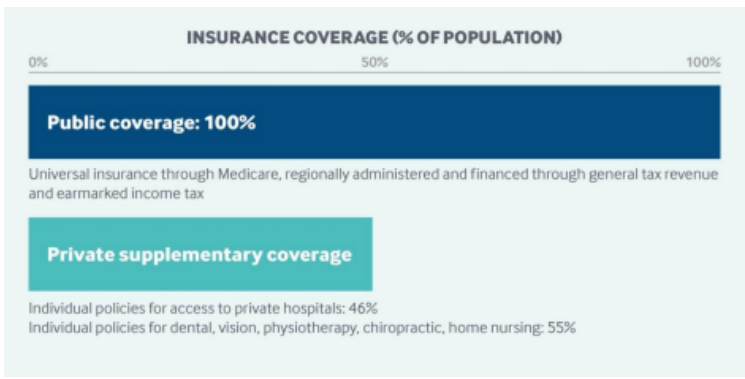

Conditional Cash Transfer Programs (CCTs)

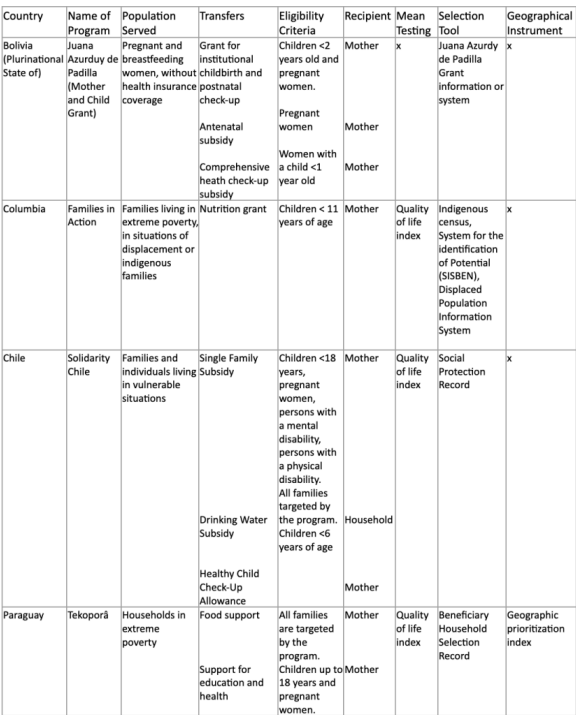

Conditional Cash Transfer programs provide or award low-income households (typically including children, pregnant women, and young family members or Indigenous persons in national territory with the possession of an identity card) monetary or non-monetary (e.g., in-kind benefits) in education, health, and nutrition (Cecchini & Madariaga, 2011). Depending on the country and its resources, some CCTs also offer additional benefits such as unemployed adults, disabled persons, and older adults, allowing families or systems without school-aged children to be eligible for services. These benefits are offered if the recipient(s) use the defined health or education services to enhance their quality of life, such as regular medical check-ups and school attendance. CCTs also provide benefits such as food supplements and school bags containing school supplies. The program also requires participation in other education and health services (e.g., guidance and counseling, educational talks, and seminars on various subjects) that target the family unit; see Borges, 2019; Cecchini & Madariaga, 2011. We see examples of this approach in the United States in vouchers or cash-like vouchers such as food stamps or EBT cards (Sun et al., 2021).

Though CCTs all share a standard structure, they vary in defining their target population, the benefits they provide, and the person responsible for relations with the program. When it comes to who receives these benefits or transfers, typically, a multi-stage process occurs to determine eligibility by employing criteria emphasizing geographic units and household selection:

- The program identifies geographical units with the highest poverty levels. This is determined using census data, household surveys, income variables, poverty maps, and unmet basic needs (e.g., access to potable water). An example is seen in the Tekoporâ program found in Paraguay. The program selects communities by a geographic prioritization score that gives 40% weight to the poverty conditions and 60% to the presence of unmet basic needs.

- Another form of selection is defining what a family unit or a household is to use as a guide. Some programs use a direct means test by using the income level or the assets that the family reports. This information is collected through ad hoc surveys or censuses initiated by the program.

- Some programs supplement family units and households by including community selection because local agents have more information on the needs and the shortcomings of the homes in their communities and are more likely to have a better idea of the socio-economic conditions of their communities. For example, the Tekoporâ program includes a community selection mechanism as a final stage.

- One more level of determination is category targeting. This low-cost approach defines populations based on easily identifiable categories that receive equal benefits. For example, the Juancito Pinot Grant program of the Plurinational State of Bolivia is only available for children attending up to the eighth grade in public schools. This is ideal for countries in which the population’s socio-economic level highly segments the social services provided.

User households stop receiving subsidies when their members no longer satisfy the eligibility conditions. For example, in some CCTs, families leave the program when their children have passed the respective age limits or have attained the maximum number of years in the program.

Table 1

Examples of CCT programs in South America

Knowledge Check

What are the typical benefits provided by Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programs, and who are the primary target groups?

- How do CCT programs typically determine the eligibility of beneficiaries?

- What is an example of geographic targeting used in a CCT program, and how does it function?

Answer – CCT programs typically provide monetary or non-monetary benefits in areas such as education, health, and nutrition. The primary target groups include low-income households, children, pregnant women, and Indigenous persons. These programs aim to improve the quality of life for vulnerable populations by incentivizing positive behaviors, such as school attendance and regular health check-ups, in exchange for receiving benefits

CCT programs determine eligibility through a multi-stage process, including geographic targeting, household means testing, community selection, and category targeting. This process ensures that the benefits are directed to the most vulnerable populations by using a combination of data-driven methods and local insights to identify those most in need.

An example is the Tekoporâ program in Paraguay, which selects communities using a geographic prioritization score that considers poverty conditions (40%) and unmet basic needs (60%). Geographic targeting helps focus resources on the areas with the highest levels of poverty and the greatest unmet needs, ensuring that the benefits reach the most disadvantaged populations.

Collaborative Private/Public Systems

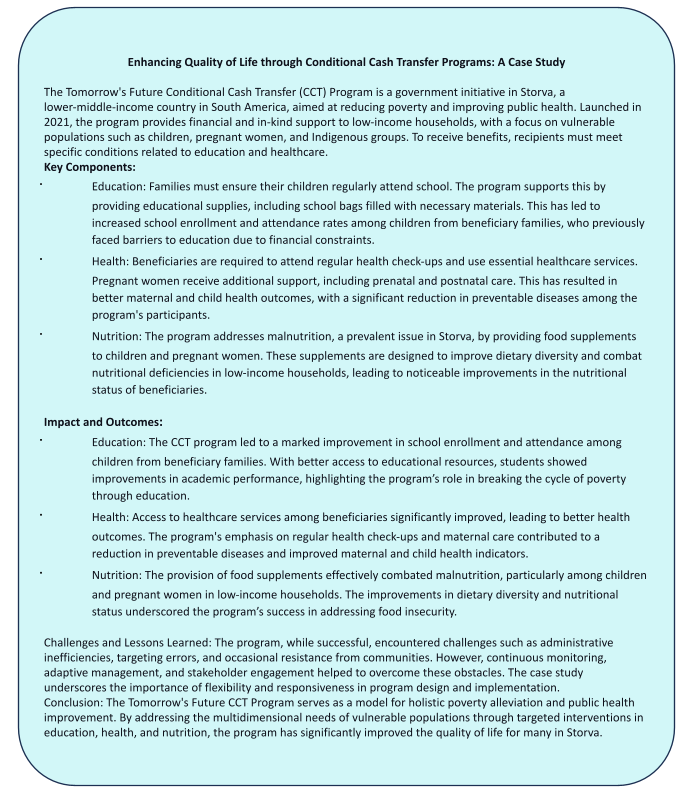

Some Asian and African countries use a mixed system of private and public collaborations. An example is Singapore, which offers universal health care coverage to citizens, with a financing system funded through government subsidies, multilayered financing schemes, and individual private savings, all administered at the national level.

As a former British colony, Singapore inherited a health system that offered its citizens universal health care coverage. However, concerns arose that free care would encourage overuse or unnecessary use, making the system unsustainable. Singapore, therefore, introduced patient copayments for outpatient services (Satkunanantham & Lee, 2015). A system of savings and insurance programs to help individuals and families pay for their care known as the “3Ms” emerged, comprised of MediShield (the primary insurance system in the country financed by the government), MediSave (medical savings accounts akin to health savings accounts in the US-funded through independent contributions or their employer) and Medifund (the government’s safety net for the neediest citizens) (Mossialos et al., 2016). While the government finances MediShield, individuals can purchase supplemental private insurance or receive it through an employer (Tan & Earn Lee, 2019). Patients are responsible for paying the insurance premium, deductibles, co-insurance, and other out-of-pocket expenses.

Due to its multi-financing system, multiple entities may cover one procedure. Through MediShield, the government subsidizes up to 80 percent of the total bill of public hospitals, primary care polyclinics, and intermediate and long-term care institutions. Individuals then would use MediSave to help cover out-of-pocket expenses. Those who cannot pay for out-of-pocket costs using MediSave rely on Medifund.

Private insurance is available from several for-profit companies, usually in MediSave-approved Integrated Shield Plans. These plans allow individuals to use funds from their MediSave accounts to pay the premiums (employers also may offer private insurance to their employees as a staff benefit).

Singapore’s health system is organized by health care services offered via public or private assistance. Primary care is administered mainly by 1,400 private general practitioner clinics (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2021). Patients can choose their primary care physician without registering. Private primary care doctors can also make referrals, bypassing the gatekeeping function like PPO insurance plans in the US. In addition, there are 18 public, multi-doctor polyclinics that provide subsidized outpatient care; these clinics generally serve lower-income populations. General care is delivered at regional hospitals that offer acute inpatient and specialist outpatient services and have 24-hour emergency departments.

Table 2

Organization of Singaporean Health Care Services

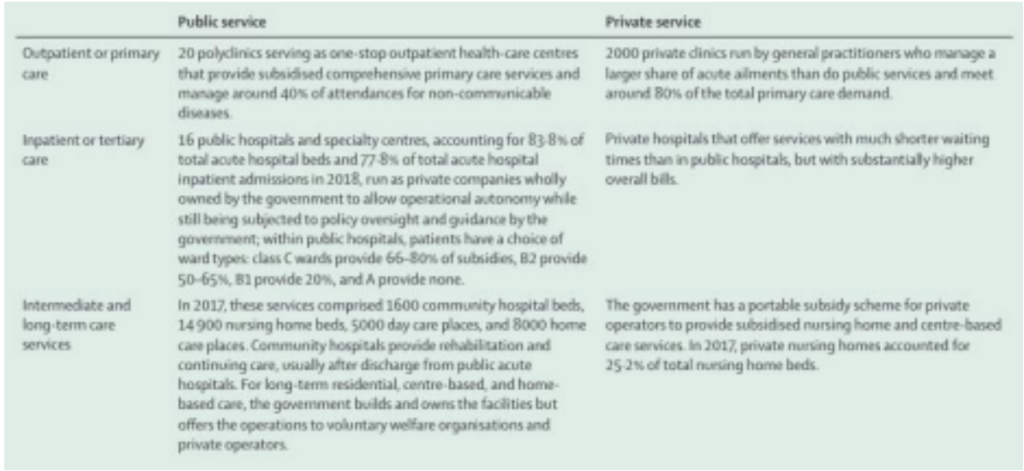

Another example of a mixed system is seen in Australia, which has the highest number of practicing physicians (3.39) per 1000 people (Dixit & Sambasivan, 2018). The Australian healthcare system is a hybrid of welfare and market models under which citizens, permanent residents, and refugees have access to free medical care in public hospitals and can access public insurance. It is funded through a complex mix of Commonwealth and state government, corporate, religious, philanthropic, and individual sources. Under the national compulsory health insurance model, Medicare is provided with complimentary or subsidized access to doctors and various medical and health facilities, even though many are in the private sector and charge on a fee-for-service basis. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme is universal and government-funded, providing patients with pharmaceuticals from privately owned pharmacies at significantly reduced costs.

Individuals can buy additional private insurance coverage for out-of-pocket fees, access to private hospitals, greater choice of providers (particularly in hospitals), faster access to non-emergency services, and rebates for selected services. Tax rebates from the government (ranging from 8.5% to 33.9% depending on age and income) and an income-based penalty payment (from 1% to 1.5%) for not having private insurance act as incentives for enrollment in private insurance schemes. In 2016, 46% of the Australian population had private hospital coverage, and nearly 55 % had private general coverage. However, only 22% of the most disadvantaged individuals in Australia have PHI coverage (Glover, 2020).

Figure 3

Private Health Insurance Coverage in Australia here

Knowledge Check

What incentives does the Australian government offer to encourage enrollment in private health insurance (PHI)?

How does the organization of primary care in Singapore’s healthcare system differ from the typical gatekeeping function seen in other healthcare systems, such as the US?

What challenges does the Australian healthcare system face in ensuring equitable access to private health insurance (PHI)?

How does Singapore’s MediShield program subsidize healthcare costs, and what role do MediSave and Medifund play in covering remaining expenses?

Answers:

- The Australian government offers tax rebates ranging from 8.5% to 33.9% based on age and income and imposes an income-based penalty payment (from 1% to 1.5%) for not having private insurance. These incentives are designed to encourage individuals to purchase private health insurance, thereby reducing the burden on the public healthcare system and giving people more choices in their healthcare providers and services.

- In Singapore, patients can choose their primary care physician without registration and private primary care doctors can make referrals, bypassing the gatekeeping function, like PPO insurance plans in the US. This system allows for greater flexibility and choice for patients, making it easier for them to access specialists and other services without needing a referral from a primary care provider, which is a common requirement in systems with gatekeeping.

- The challenge is that only 22% of the most disadvantaged individuals in Australia have PHI coverage, despite incentives like tax rebates and penalties for not having insurance. This disparity indicates that even with financial incentives, lower-income populations may still find private health insurance unaffordable or unnecessary, leading to unequal access to healthcare services and benefits provided through PHI.

- MediShield subsidizes up to 80% of the total bill in public hospitals, primary care polyclinics, and other long-term care institutions. MediSave helps cover the remaining out-of-pocket expenses, and Medifund steps in when individuals cannot cover these costs through MediSave. This tiered system ensures that the majority of healthcare costs are covered by the government, with individuals using their savings for additional expenses, and a safety net is available for those in need, ensuring no one is left without care.

Conclusion

Healthcare delivery systems outside the US vary from region to region, with each country employing differing models that work best for its population. However, since no health care system is alike or devoid of challenges, a method that may work for one country is not likely to be transferable due to different health concerns, priorities, and funding resources. However, as more societies regard healthcare as a social or collective good, the gap between the types of healthcare delivery systems and health insurance plans utilized by UMIC, HIC, and LMIC needs to be addressed.

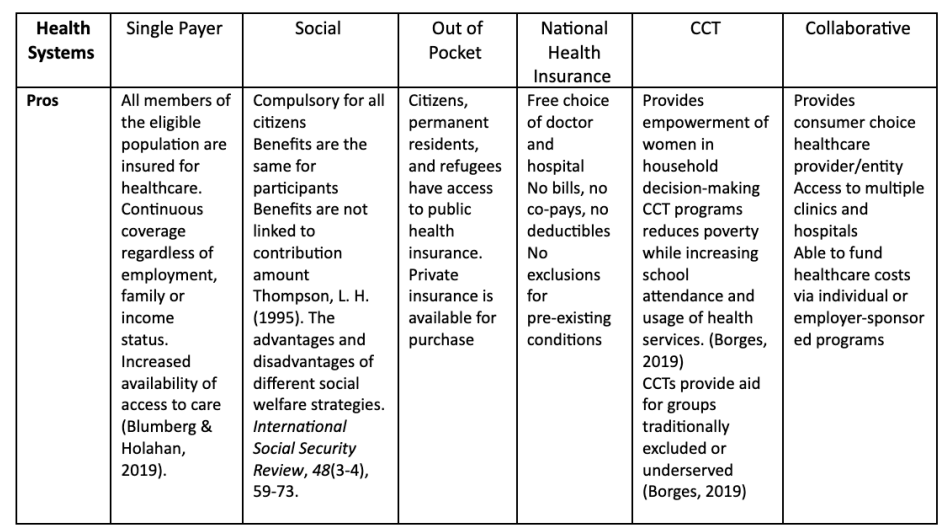

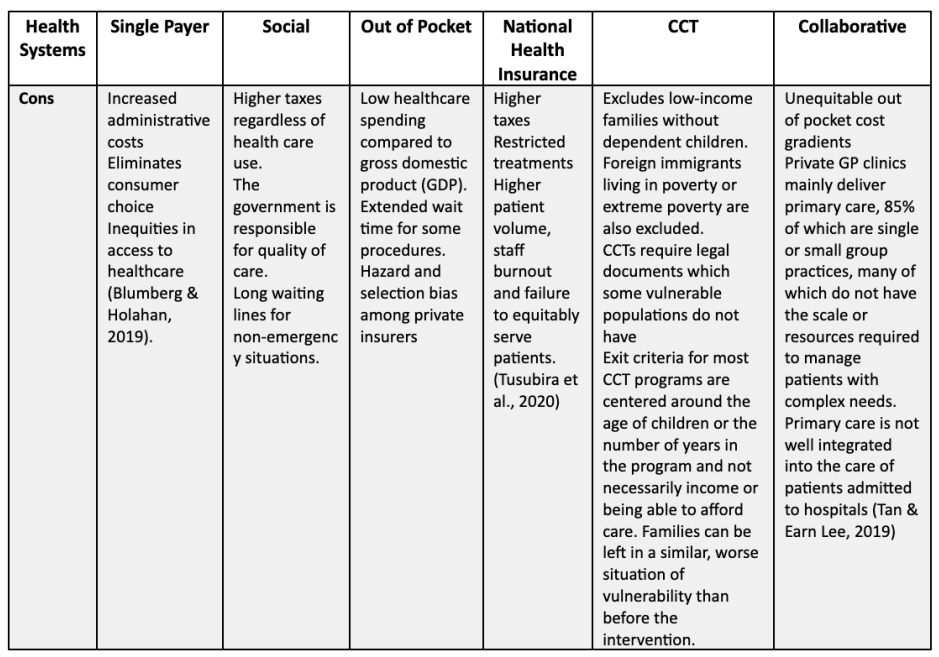

Table 3

Pros and Cons of Each Health System

The formation of adaptable and flexible new or hybrid healthcare financing and delivery systems are avenues through which LMICs could adopt healthcare systems or models that facilitate availability, accessibility, affordability, and sustainability.

Key Words

Conditional Cash Transfer: Conditional cash transfers are social assistance programs aiming to reduce poverty.

Universal Health Coverage: Universal health coverage means that all people have access to the health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship.

Single-payer national health service: a system in which a single public agency organizes health care financing, but care delivery remains mainly in private hands.

Social health insurance model: Social Health Insurance is a form of financing and managing health care based on risk pooling.

Market-driven health care: this model is found in most of the world. It is used in countries that are too poor or disorganized to provide any national health care system. In these countries, those that have money and can pay for health care get it, and those that do not stay sick or die.

National Health Insurance model: The national health insurance model is driven by private providers, but the payments come from a government-run insurance program to which every citizen contributes. Essentially, the national health insurance model is universal insurance that doesn’t make a profit or deny claims.

References

Borges, F. A. (2019). Adoption and Evolution of Cash Transfer Programs in Latin America. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

Busse, R., Blümel, M., World Health Organization. (2014). Germany: Health system review. WorldHealth Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/130246

Busse, R., Blümel, M., Knieps, F., & Bärnighausen, T. (2017). Statutory health insurance in Germany: A health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. The Lancet, 390(10097), 882–897.

Canadian Life & Health Insurance Association. (2021). Canadian life and health insurance facts. Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. http://clhia.uberflip.com/i/1409216-canadian-life-and-health-insurance-facts-2021/29?

Cecchini, S., & Madariaga, A. (2011). Conditional cash transfer programmes: The recent experience in Latin America and the Caribbean. Cuadernos de la CEPAL(95).

Chowdhury, S., Gupta, I., Trivedi, M., & Prinja, S. (2018). Inequity & burden of out-of-pocket health spending: District level evidences from India. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 148(2), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_90_17

Chung, M. (2017). Healthcare reform: Learning from other major healthcare systems. Princeton Public Health Review.

da Lilly‑Tariah, O. B., & Sule, S. S. (2020). Universal healthcare coverage and medical tourism: Challenges and best practice options to access quality healthcare and reduce outward medical tourism in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine, 29(3), 351–361.

Dixit, S. K., & Sambasivan, M. (2018). A review of the Australian healthcare system: A policy perspective. SAGE Open Medicine, 6, 2050312118769211.

Gambhir, R. S., Malhi, R., Khosla, S., Singh, R., Bhardwaj, A., & Kumar, M. (2019). Outpatient coverage: Private sector insurance in India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(3), 788.

Glover, L. (2020). International healthcare system profiles: Australia. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/australia

International Finance Corporation. (2016). The business of health in Africa: Partnering with the private sector to improve people’s lives. https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2016-01/IFC_HealthinAfrica_Final_0.pdf

Gupta, I. (2020). International health care system profiles: India. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/india

Light, D. W. (2003). Universal health care: Lessons from the British experience. American Journal of Public Health, 93(1), 25–30.

Maphumulo, W. T., & Bhengu, B. R. (2019). Challenges of quality improvement in the healthcare of South Africa post-apartheid: A critical review. Curationis, 42(1), 1–9.

Ministry of Health Singapore. (2021). Health Facilities: Resources and Statistics. https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/health-facilities

Mossialos, E., Wenzl, M., Osborn, R., & Sarnak, D. (2016). 2015 international profiles of health care systems: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Mukhopadhyay, I., & Sinha, D. (2019). Painting a picture of Ill-health. In Azad, Chakraborty, S., Raman, S., & Sinha, D. (Eds.), Quantum leap in the wrong direction, Orient Black Swan.

Satkunanantham, K., & Lee, C. E. (2015). Singapore’s health care system: What 50 years have achieved. World Scientific.

Skolnik, R. (2021). Chapter 6: An introduction to health systems. In Global Health 101 (4th ed., pp. 117–164). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Sun, S., Huang, J., Hudson, D. L., & Sherraden, M. (2021). Cash transfers and health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 363–380.

Tan, K. B., & Earn Lee, C. (2019). Integration of primary care with hospital services for sustainable universal health coverage in Singapore. Health Systems & Reform, 5(1), 18–23.

Thorlby, R. (2020). International health care profiles: England. Retrieved from The Commonwealth Fund website: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/england

Thorlby, R., & Arora, S. (2018). The English health care system. International profiles of health care systems, 52-70. The Common Wealth Fund.

WHO. (2021, April). Universal health coverage. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)