15

Health Disparities

Vierne E. K. Placide, PhD, MPH, CPHQ

State University of New York College at Cortland

Heather Craig Alonge, PhD, MPH, MCHES

Walden University

“It is health that is the real wealth, and not pieces of gold and silver.” – Mahatma Gandhi

Learning Objectives

- Develop an understanding of health disparities in the US

- Discuss how these disparities are a consequence of systemic and societal issues

- Describe population groups facing greater challenges in accessing and receiving quality care

- Explore strategies for reducing and/or eliminating health disparities

Introduction

In comparison with other developed nations, the US spends the most on healthcare, but has the worst outcomes. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it should not be

sufficient to support and advance the health for the average population, if inequality and inequity continues to exacerbate; because any gains accumulated are reflected in population groups who already have better health (2000). Disparities in health status, such as life expectancy, are a direct reflection of social and economic inequalities. Disparities are not a new phenomenon. Historically, our healthcare system has been marked by inequities rooted in racism and discrimination (Ndugga & Artuga, 2021). Disparities constitute preventable and inequitable differences in health experiences and outcomes among population groups.

A health disparity occurs when one group experiences a higher burden of illness, injury, disability, violence, or mortality than another; while a health care disparity involves differences in insurance coverage, quality of care, access, and utilization between groups (Brottman et al., 2020; Ndugga & Artiga, 2021; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 2022). Disparities exist across many dimensions including gender identity, sexual orientation, disability status, socioeconomic status (SES), citizenship status, location/region, age, and race/ethnicity (Ndugga & Artiga, 2021; Walston & Johnson, 2021). The estimated economic burden of disparities is $42 billion in productivity loss, and $93 billion in excess health care costs (Ndugga & Artiga, 2021, para. 11). To overcome this burden and improve the overall health of the nation, it is imperative to implement strategic priorities and practices that address reducing and/or eliminating disparities.

The objective of this chapter is to provide an understanding of health and healthcare disparities in the US.The first section of the chapter delves into the historical context of policies and practices that have generated disparities. The chapter then discusses the multidimensional facet of health. The chapter also describes the status of disparities, highlighting groups with poorer health outcomes, who face greater challenges and barriers in accessing and receiving quality healthcare services. The chapter concludes with current efforts to address disparities, strategies to improve healthcare delivery for vulnerable populations, and reinforces the rationale and urgency to eliminate disparities.

Historical Context

The present is informed by history. Rosen stated, “every social phenomenon is the result of historical process, that is societal factors operating over a period of time through human interaction…. As soon as large-scale phenomena are investigated, account must be taken of the historical facet” (1973, p. 55). These processes led to the imbalance of power and differential access to education, employment, housing, and health. The accumulation of pivotal public policy decisions has overtime shaped the disparities being experienced in healthcare today (Chowkwanyun, 2011). Among the many examples are slavery, residential segregation, and the unequal distribution of economic, environmental, and labor resources.

Patterns of residential segregation based on race and income were ingrained in policy and are noted in books such as Making the Second Ghetto, Origins of the Urban Crisis, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Institutionalized (economic, legal, political) systems resulted in “urban redevelopment” displacing many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) and lower- income populations to public housing exclusively in segregated neighborhoods, safeguarding neighborhood homogeneity (Chowkwanyun, 2011; Williams et al., 2019). This also impacted the labor market, which moved jobs away from these areas. BIPOC populations faced additional employment discrimination in recruitment, apprenticeships, and promotions (Chowkwanyun, 2011). Ideals deep-rooted in policies which limited resources to certain communities – strategic zoning of residential neighborhoods, environmental hazards, job discrimination, and residential segregation – are not the result of individual behaviors but are systemic decisions which have continually resulted in the oppression and inequalities experienced by BIPOC populations.

The “relocation” of American Indian and Alaska Natives to tribal lands is another example which has had an adverse impact on health equity (Williams et al., 2019). American Indian and Alaska Natives access to quality medical care is consistently hindered – although the government is required to provide health care services to federally recognized tribes, policies and resources are often limited in comparison to other federal programs (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2003). While Indian Health Services (IHS) is a great mechanism for providing services, only about 22% of American Indian and Alaska Natives live on tribal lands, which leaves a large majority who may not have access to IHS facilities, since most are in remote areas on or near tribal lands (IHS, 2019; IOM, 2003).

Within the BIPOC community, a lack of trust in the health system can be traced back to the history of slavery, segregation, prejudice, and medical experimentation (Betancourt et al., 2013). Inhumane medical experiments such as sterilization, plutonium injections, negative eugenics, and other research inquiries were often involuntary and without consent or the knowledge of the victims. For instance, Dr. James Marion Sims was credited for gynecology advances such as correcting vesicovaginal fistula (Lynch, 2020; Washington 2007). However, this was achieved by using Black/African American babies for tetany experiments and exploiting Black/African American female slaves through brutal surgeries performed without anesthesia (stemming from the misconception which still exists today that Black/African American individuals experience pain differently) (Lynch, 2020; Washington 2007). Once the surgical method was perfected, the technique was used on White women with anesthesia (Lynch, 2020). Additionally, eugenics initiatives in the United States allowed government officials in public health, social welfare, and state institutions to sterilize individuals deemed “unfit” (Novak & Lira, 2018). The approximately 60,000 sterilizations targeted populations based on race/ethnicity (American Indian and Alaska Native, Black/African American, and Latinx), socio- economic status, and ability (physical and mental) (Novak & Lira, 2018; Pacheco et al., 2013).

Due to concerns of a diabetes epidemic among the Havasupai Tribe, members approached an anthropologist at Arizona State University, who agreed to provide education, arrange for testing to determine those at risk, in addition to genetic testing to see if there were correlations (Pacheco et al., 2013). However, blood samples taken for the diabetes study were mishandled and utilized for behavioral health -schizophrenia and depression- research without permission (Pacheco et al., 2013). In the 1960s and 1970s when the Department of Defense expanded its radiological research, the majority (60%) of those experimented on were poor, uneducated, and Black/African American (Stephens, 2002). The patients were not informed of the dangers of receiving high doses of whole-body radiation which were of no benefit to their incurable cancer (Stephens, 2002). Similarly, the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male was continued unethically for 40 years at the mistreatment of Black/African American people by the government (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021a, Feagin & Bennefield, 2014). The neglect and abuse of the BIPOC community in addition to indigent populations in the healthcare system has carried on into modern healthcare where the effects of prejudice and disparate treatments are still experienced (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014).

Health and healthcare disparities are a result of a host of personal, societal, and systemic factors, including racism (individual, cultural, structural, and institutional). Racism is defined as conditions – policies, practices, systems, and norms – that give value and privilege to some people, and results in conditions that disadvantage others based on the color of their skin (CDC, 2021d, para. 1; Ndugga & Artica, 2021). Cultural racism fosters implicit biases and stereotypes. Associating BIPOC populations with inferiority through imagery, norms, and the cultural belief system (Williams et al., 2019). There is a persistent culture of stereotypes towards BIPOC, such as being violent, unskilled, and dependent on public assistance (IOM, 2003). This translates into discriminatory experiences in the healthcare system. “Racial framing” flows over into health systems when medical decisions are shaped by systemic discrimination. Racism is the risk factor of poor health outcomes, not race (Black et al., 2020). The abuse BIPOC populations face now, unfortunately frequently mirrors the abuse of the past (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014). On the surface, while there are some improvements in attitudes toward BIPOC, when asked about policies and processes that enhance interaction with these populations, support declines (IOM, 2003). Racial discrimination exacerbates societal inequities on the micro, meso, and macro levels (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014; Williams et al., 2019).

A glimpse into the political and institutionalized systems which revolutionized social structures expose the disparities which continue to exist today, and the intergenerational trauma created as a result. Many institutions and systems in the US, including healthcare, have been structured to serve the “White cisgender majority,” leaving others to conform to the system in order to obtain care. Healthcare is plagued by several systemic social structures which influence population-level characteristics and place a greater burden on vulnerable populations. Social constructs such as race and SES play a significant role in daily life experiences, including one’s health.

Social Determinants of Health

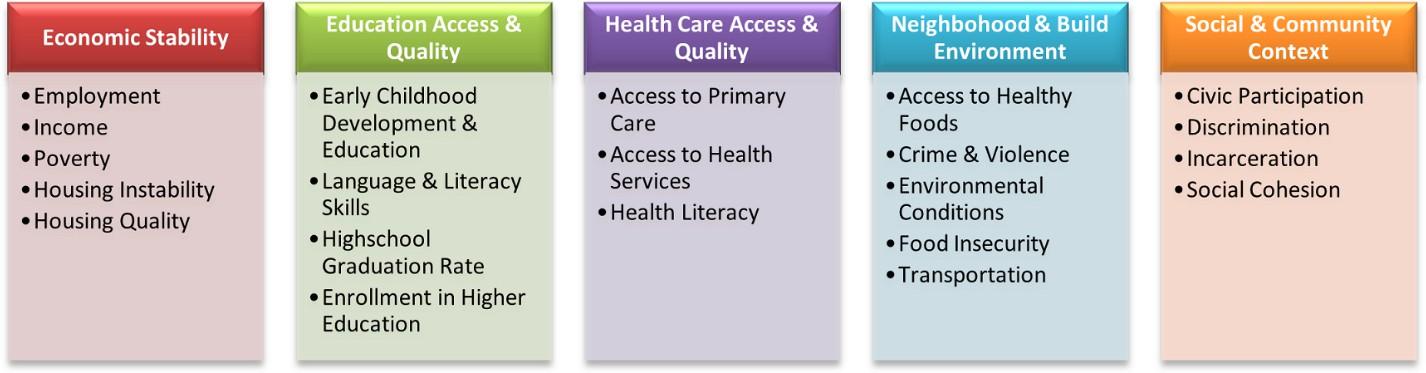

The concept of health is characterized by its multidimensionality, affected by a patient’s individual, social, economic, and environmental factors (Barr, 2019). Failure to integrate these systems and social structures result in health inequities (Jones et al., 2019; Siegel et. al., 2018; WHO, 2008). The social determinants of health (SDOH) are the “conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” (ODPHP, n.d.c, para. 1). There are five SDOH domains: 1)economic stability, 2) education access and quality, 3) health care access and quality, 4) neighborhood and built environment, and 5) social and community context.

Figure 1

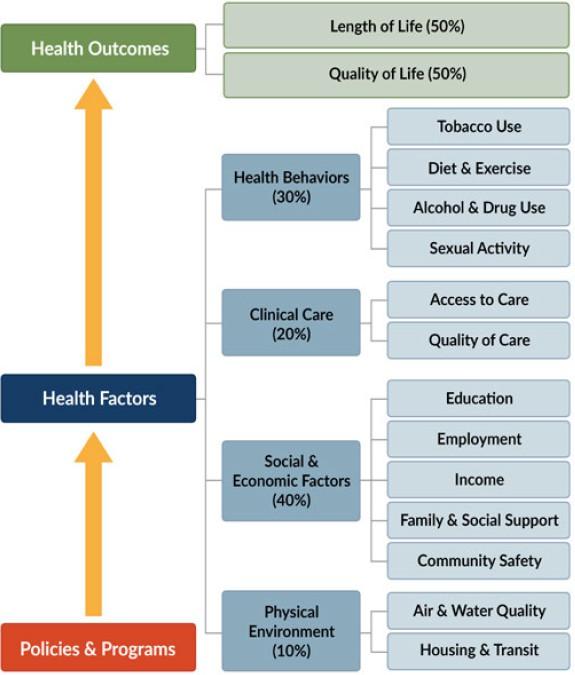

Figure 1 navigates the aspects in each SDOH domain. Incorporating SDOH in patient care shifts the focus solely on individual level characteristics to each domain. For instance, recognizing the impact of poverty on inequitable access to healthcare, economic imbalances of other resources, as well as the neighborhood and built environment. An assessment of the built environment considers limited access to healthy food options (fresh fruits and vegetables), sidewalks, or a neighborhood park; and the correlation to chronic illnesses, as people living in poor communities face an increased risk of chronic diseases, shorter lifespan, and death (ODPHP, n.d.b.). Equitable access to safe affordable housing, transportation, quality education, and jobs influence the quality of daily life and health. The County Health Rankings Model is illustrated in Figure 2, which highlights the underlying elements that impact health outcomes.

Figure 2

The historical context shapes the social and environmental factors which ultimately affect individuals’ health behaviors and population health. Disparities occur when population groups are not treated equally or fairly, or when specific groups bear disproportionate incidence of disease or injury.

Current Status of Health and Healthcare Disparities

Despite documentation of disparities over the decades, various forms continue to exist within the US Healthcare system. In some cases, the disparities have not only persisted but widened (Ndugga & Artiga, 2021). Access to services and quality of care contribute to disparities experienced by people living in medically underserved areas including individuals living in inner city and rural communities, people with lower SES, BIPOC populations, persons who identify as LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning), patients diagnosed with a mental health illness, HIV/AIDS or a disability. People with disabilities report worse health problems than those who are healthy, stemming from inequalities of access to health care (Krahn et al., 2015). As the cost of health insurance continues to rise, many disabled people cannot afford it. Despite significant progress in expanding Medicare, 28% of people with disabilities remain uninsured (Krahn et al., 2015). Additionally, healthcare costs are a major reason why adults with disabilities are 2.5 times more likely to delay or not seek care (Krahn et al., 2015). This section discusses some of the more prominent disparities experienced in our healthcare system, in addition to the lack of skills and/or knowledge of the healthcare workforce to care for vulnerable patients’ complex needs. Racial and ethnic disparities are particularly pronounced.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

Almost two decades ago, The Institute of Medicine released The Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care report to highlight disparities in care and health outcomes experienced by racial and ethnic populations (2003). Despite this report, a great deal of progress has yet to be made. Even more alarming, the US census projects BIPOC to be the majority by the mid-2040s (Frey, 2018). In the US, race and ethnicity have played a critical role in affecting health status. The BIPOC community has a greater risk of disparities and is disproportionately affected by treatable medical conditions (Betancourt et al., 2013; IOM, 2003; Placide & Vance, 2021; RWJF, 2014).

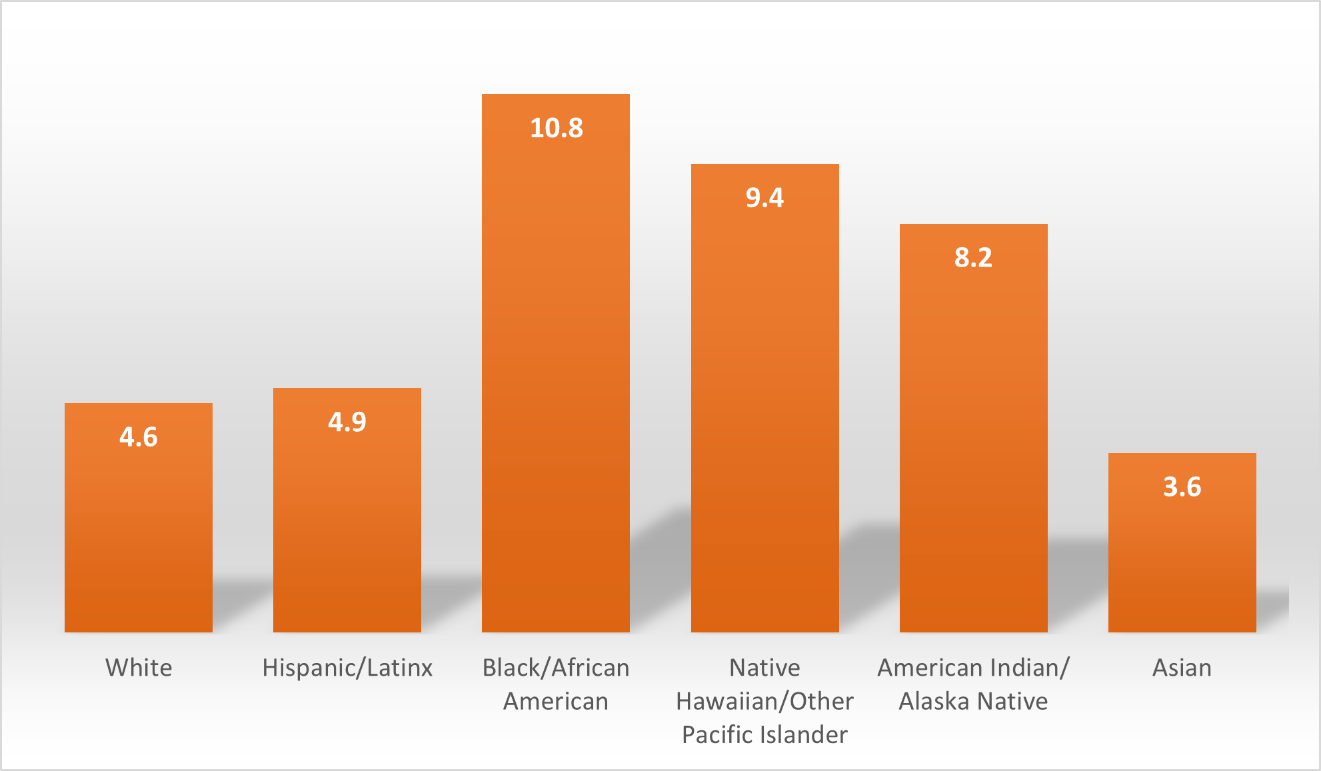

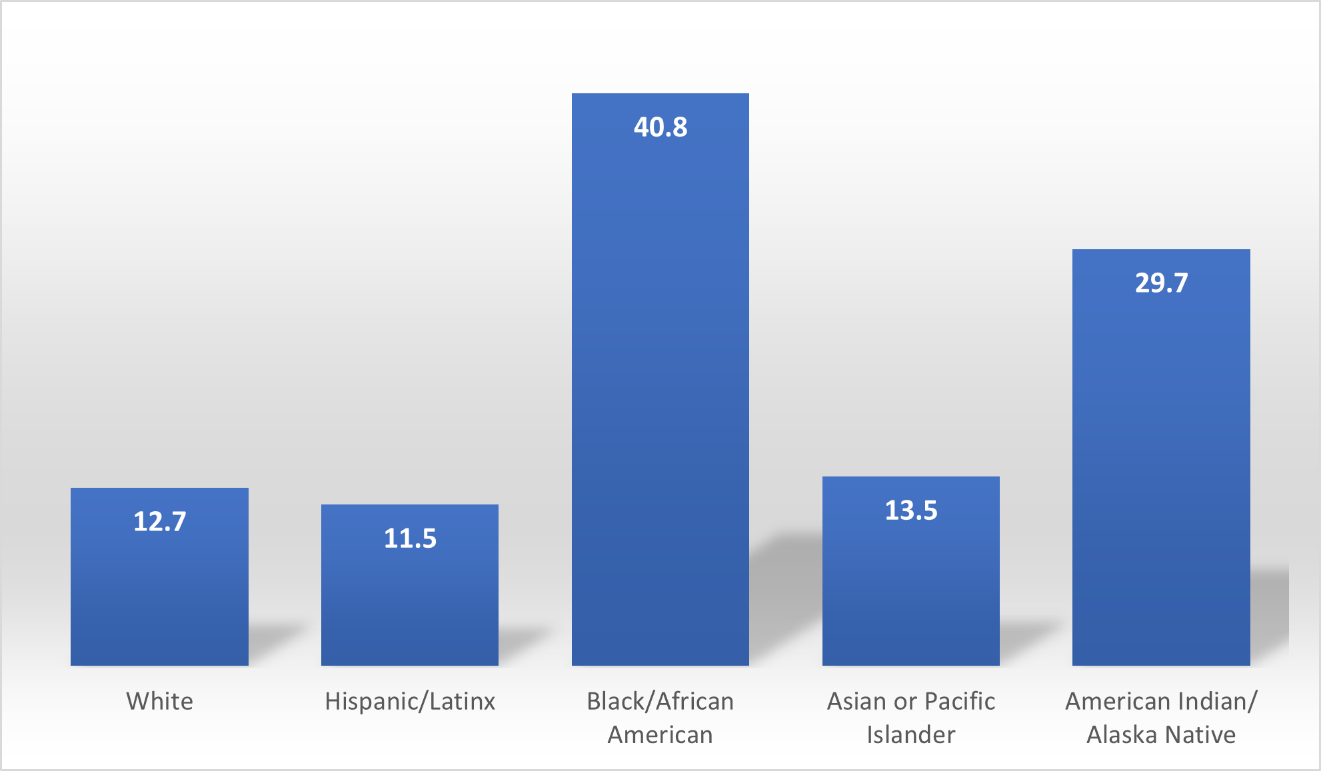

These risks exist from cradle to grave. Although the infant mortality rate (the death of an infant before their first birthday per 1,000 live births) is declining, there are startling disparities (Figure 3). The rate for Black/African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and American Indian and Alaska Native infants is two to three times higher than the rate of Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, and White infants. The maternal mortality rate for Black/African American and American Indian and Alaska Native women is also alarming (Figure 4). Pregnancy-related deaths are two to three times higher and increases in age in comparison to White women (Artiga et al., 2020, para. 4; CDC, 2019). Prevalent chronic illnesses (i.e., hypertension and diabetes) also adds higher risks of pregnancy-related complications for BIPOC mothers and babies. When controlling for SES factors the disparity still exists or widens in some cases, which is connected to the historical context of oppression and segregation. The maternal mortality rate is 1.6 times higher for Black/African American women with a college degree than White women with less than a high school diploma, and five times higher for Black/African

American women with a college education in comparison to White women with the same education (Artiga et al., 2020; CDC, 2019). The US is the only industrialized nation where the maternal mortality rate is increasing.

Figure 3

Figure 4

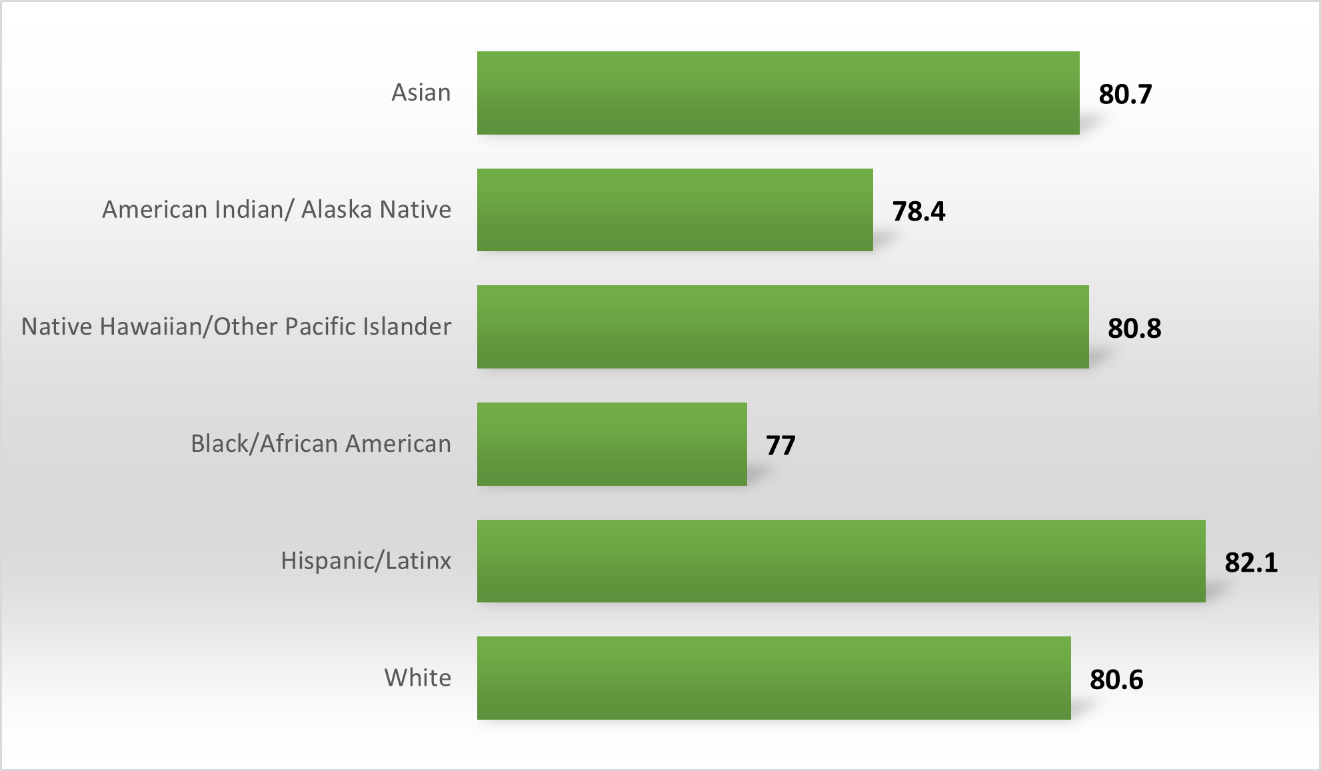

Similar to the maternal mortality disparity, Black/African American, and American Indian and Alaska Native population have a shorter life expectancy in comparison to other population groups (Figure 5). This life expectancy gap widens in geographical locations, for instance it exceeded 10 years in Washington, D.C. (Roberts et al., 2020). Several factors

-discrimination, housing, geographic locations, income, chronic illnesses, cultural barriers- contribute to the intergenerational deprivation and absence of receiving quality care (Office of Minority Health [OMH], 2021).

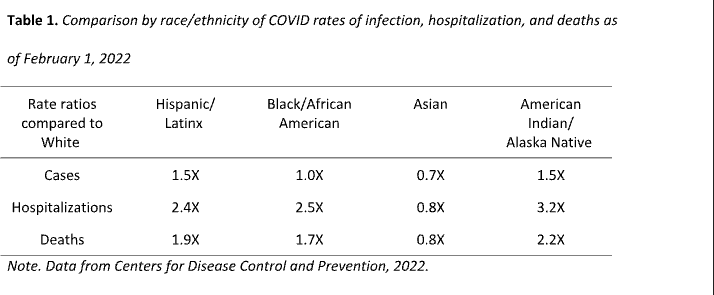

Figure 5

Variations also exist in preventative care and chronic illnesses which are seen in SES and racial/ethnic disparities. BIPOC have higher rates of cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and obesity than White individuals (Thorpe et al., 2017). Among the most prevalent chronic diseases, cardiovascular disease, accounts for the largest disparity in life expectancy between Black/African American and White individuals (Carnethon et al., 2017). The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic amplified the cumulative inequities, and rates of infections and mortality experienced by populations who identify as BIPOC as shown in Table 1. It exposed shortcomings and complexities in the healthcare system which negatively impact certain populations more than others.

Table 1

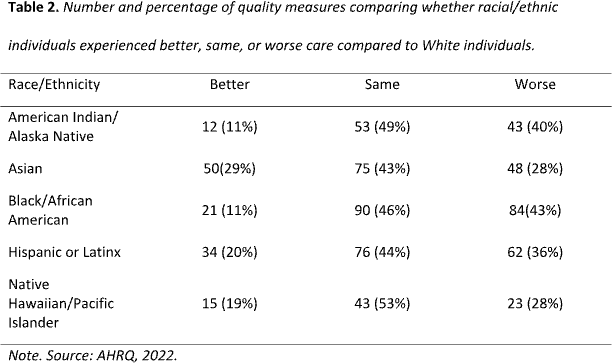

The quality of care provided to BIPOC populations is consistently lower than that of White individuals, even after controlling for several factors such as comorbidities and SES factors (Betancourt et al., 2013; IOM, 2003; RWJF, 2014; Wilbur et al., 2020). As illustrated in Table 2, The Agency for Healthcare research and Quality (AHRQ) noted that while

some quality-of-care measures have improved, others have stayed the same or worsen in BIPOC communities.

Table 2

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

People who identify as LGBTQ+ are more likely to face health challenges associated with stigma and discrimination (Altman, 2021; Ndugga & Artiga, 2021; Walston & Johnson, 2021). As a result, LGBTQ+ individuals may delay care due to real and perceived inequities, and are at higher risk for substance use, psychological distress and accessing care (Walston & Johnson, 2021). Additionally, this population may suffer from chronic illnesses or disabilities, and are more likely to be low income (Altman, 2021). In comparison to their cisgender peers, LGBTQ+ youth are more likely to be bullied, engage in high- risk sexual behaviors, use illicit substances, and seriously consider suicide (CDC, 2019b; Hafeez et al., 2017). It is important to recognize that LGBTQ+ individuals face many structural barriers to health, including the lack of culturally congruent healthcare practitioners who are trained to address their needs.

Although this section focuses more on the LGBTQ+ community, there are also disparities between men and women. Despite having lower mortality rates and less risky behaviors than men, women still suffer from many physical and mental health inequalities (Sagynbekov, 2017). Disparities based on gender are greatest in southern states and lowest in northeastern states (Sagynbekov, 2017).

Geographic Location

Where you live plays a critical role in your health status. “Your zip code is a more powerful predictor of your health than your genetic code” (Williams, n.d., as cited in Yale Medicine Magazine, 2012, para. 1). People who live in small and medium cities, non-metropolitan areas, inner cities and rural communities, experienced worse health outcomes, which have remained stagnant overtime (AHRQ, 2022). The US counties with the lowest health status were regions – Tribal Lands, Appalachia, South – with historical inequities stemming from racism, discrimination, and a lack of allocated resources (RWJF & UWPHI, 2020). Lower income neighborhoods often lack access to quality healthcare, quality foods, and quality education (Ailshire & Garcia, 2018). People’s living environments have the potential to either enhance or hinder their quality of life.

In rural communities, having optimal health is challenging because of barriers such as environmental hazards, being uninsured, poverty, transportation, and long travel distances to access healthcare (CDC, 2017; Shi & Singh, 2017). Maldistribution of practitioners is a major issue in rural areas. Only 11% of physicians practice in rural areas, although 20% of the US population live in these communities (Jaret, 2020). These challenges result in delayed care, increased morbidity, and increased mortality rates. Residents of rural communities are more likely to die from unintentional injuries, cancer, heart disease, stroke, and chronic lower respiratory disease in comparison to residents of urban communities (CDC, 2017).

Land use regulations, particularly zoning -the process of designating areas as residential or industrial- is a significant contributor of disparities. Communities with a high concentration of Black/African American individuals were more likely to be zoned for higher density, and areas more likely to be zoned for industrial use had a high concentration of Black/African Americans and immigrants (Shertzer, et al. 2016). When continuously exposed to the waste products generated by industrial plants, the quality of life decreases for residents. Regulations and systems of the past continue to have a profound impact on the current health status of many; and further reinforces the urgent need for a coordinated effort to eliminate health and healthcare disparities. In the county health rankings, food insecurity, child poverty and fair or poor health status was linked to “severely cost burdened” households (RWJF & UWPHI, 2020). Individuals living at or below the poverty level in the US, often face many challenges and hardships in accessing and utilizing health services.

Socioeconomic Status

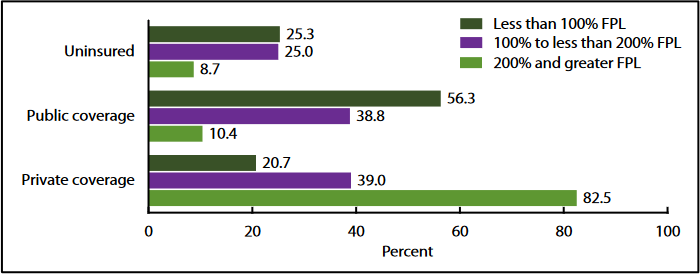

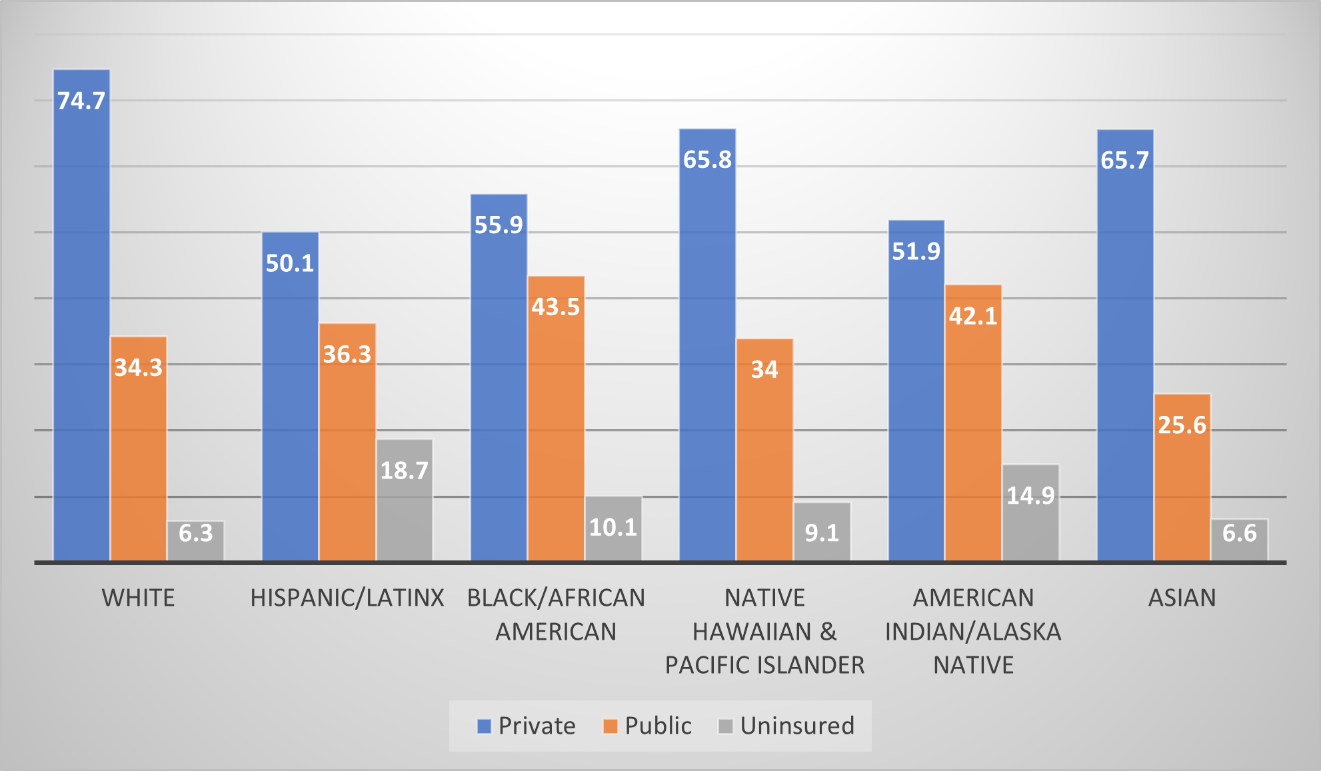

The interconnectedness of health and SES cannot be overstated. A person’s income and other measures of social status affect health directly, as well as indirectly by impeding access to care (Barr, 2019; Khullar & Chokshi, 2018). Individuals with low SES have greater rates of behavioral risk factors such as substance use, smoking, insufficient physical activity, and obesity (Khullar & Chokshi, 2018). People with lower SES also experience worse care in comparison with higher income individuals (AHRQ, 2022; Khullar & Chokshi, 2018; Ndugga & Artiga, 2021). Preventative and tertiary care differ significantly. Disparities exist in access to health insurance as depicted in Figure 6; in addition to general access to healthcare, and timely access to services (AHRQ, 2022). Approximately nine percent of the population is uninsured (Khullar & Chokshi, 2018). Creating barriers for routine preventative healthcare and challenges in coordinating care, which may result in increased visits to the emergency department by this population.

Figure 6

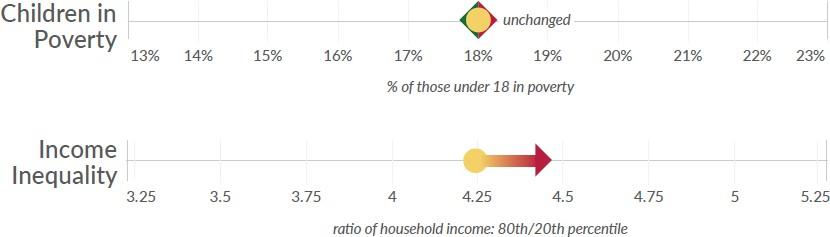

In the US, income-based health disparities are among the largest in the world, where adults living in poverty are five times as likely to report being in fair or poor health (Khullar & Chokshi, 2018). Poverty affects approximately 43 million Americans and is associated with an increased risk of diseases and premature death (ODPHP, n.d.b). The distribution of wealth in the US is even more unequal than income, which plays a crucial role in intergenerational health disparities (Khullar & Chokshi, 2018). During the last two decades, the income for poor and middle Americans has decreased (Thorpe et al., 2017). The widening income gap, and the percentage of children experiencing poverty are crucial SES challenges that have an impact on health (Figure 7).

Figure 7

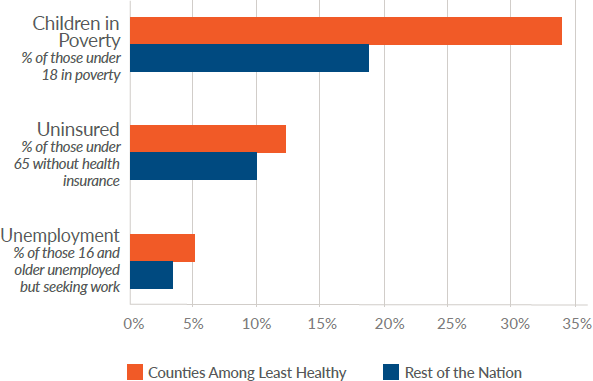

Inequitable access to resources and opportunities can be caused by a variety of reasons, leading to poverty (ODPHP, n.d.b). Counties that were among the least healthy had greater rates of poverty, uninsured people, and unemployment than the rest of the country as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Undocumented Immigrants

Over 40% of the uninsured population are undocumented immigrants who do not qualify for employer-sponsored coverage despite working, and therefore having significant barriers to access care (Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF]; Wallace et al., 2013). The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act Marketplace are systems which strive to remove access and utilization impediments for lower socio-economic status populations; however, these all have eligibility restrictions which limits undocumented immigrants from obtaining insurance coverage (KFF, 2022). Only some states have programs and services to assist immigrants in receiving care. For instance, 18 states have chosen to expand CHIP coverage to undocumented immigrants to provide prenatal care (KFF, 2022).

Increase risks of diabetes, hypertension, and other chronic illnesses are of concern due to the high rates of obesity among undocumented immigrants (Wallace et al., 2013). Although access to medical care for disease management is crucial, due to fears of being reported, seeking care for needed services deteriorated during the 2016 – 2020 administration because of immigration policies which focused on limiting public assistance to immigrant families and immigration enforcement (KFF, 2022). A further concern is the negative impact of social determinants of health including poverty, literacy challenges, housing, and food insecurities in this demographic (Chang, 2019). The connections between health and race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, SES, age, ability, nationality, and geography are complex (AHRQ, 2022). Intersectionality refers to viewing identities “not as unitary, mutually exclusive entities, but as reciprocally constructing phenomena that in turn shape complex social inequalities” (Collins, 2015, p. 2). Vulnerable populations often identify with multiple categories linked to disadvantages -economic, environmental, and social. Individuals who identify as BIPOC are more likely to have a lower SES and live in poor resource regions. BIPOC experience higher rates of chronic illness, lower wages, and have inadequate insurance coverage, which further restricts access to care, often forcing them to delay treatment or work while sick (ODPHP, n.d.b; Thorpe et al., 2019). Figure 9 shows the intersection of SES and race/ethnicity.

Figure 9

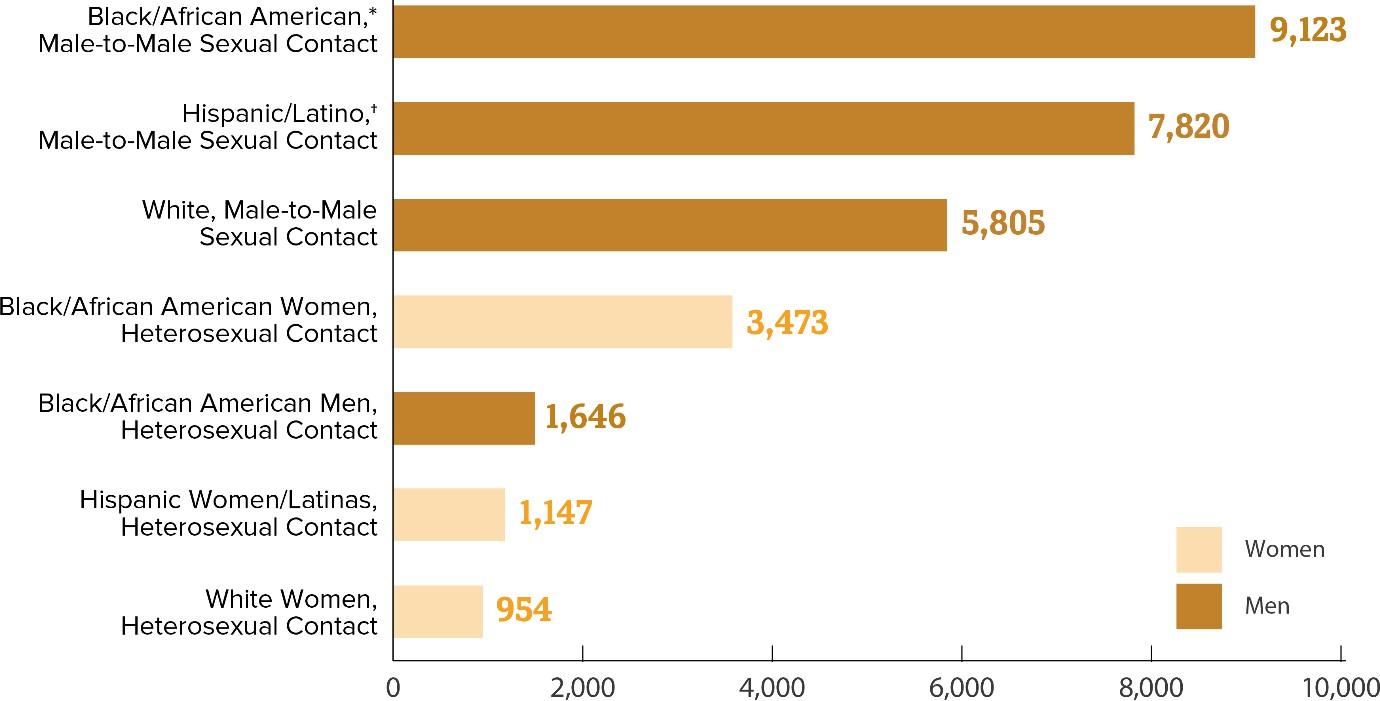

Disparities in HIV (Human Immunodeficiency virus) diagnoses

and deaths are seen in various population groups. Figure 10 highlights the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation in relation to new HIV diagnoses. Gay and bi- sexual men make up 2% of the population, yet account for 66% of new diagnoses (male-to-male sexual contact), and an additional 4% related to injection drug use (KFF, 2021). Black/ African Americans and Latinx populations make up the two highest rates of new HIV diagnoses (KFF, 2021). Although Black/African American comprise less than 13% of the US population, 40% of people living with HIV (PLWH) are Black/ African American (KFF, 2021). Treatment has dramatically improved the life span of PLWH; however, the age-adjusted death rate is highest in Black/African American and Latinx populations (KFF, 2021).

Figure 10

Various factors determine an individual’s ability to access and receive quality care, though the healthcare system is not equitable. Equity recognizes that every patient entering the health system does not have the same level of resources.

Disparities in Care

The ecological experiences over one’s lifetime, including clinical encounters, contribute to adverse health outcomes. Vulnerable populations are less likely to be educated about preventative measures and screened or referred for effective treatments by practitioners (Barr, 2019). Communication obstacles, bias, prejudice, and mistrust all contribute to inequities in medical decisions during the clinical encounter and impact the delivery of care (Betancourt et al., 2013). Biases have detrimental effects on patients and limit health organizations’ ability to make progress (Betancourt et al., 2013; FitzGerald et al., 2017). Unconscious bias towards BIPOC, LGBTQ+, lower SES and other vulnerable populations, reflects the nation’s historical and cultural views (Betancourt et al., 2013; Schnierle et al., 2019). When substantially combining attributes to generalized outcomes, practitioners may not be aware of their unconscious bias (Betancourt et al., 2013; Schnierle et al., 2019). Prejudice on the other hand, is the deliberate processing of information based on specific groups. Bias and other forms of discrimination is detrimental to the care continuum if not addressed (Betancourt et al., 2013). For instance, assuming patients are overstating symptoms, having low expectations patients will adhere to treatment regiments, not screening patients, or making referrals for specialty care based on their backgrounds (i.e. SES, racial/ethnic). Research indicates that being treated for the same diagnosis by the same practitioner, in the same healthcare system, even when controlling for health insurance status, education, and income, BIPOC populations receive worse care. LGBTQ+ individuals (especially youth) find it difficult to communicate their sexual identities with healthcare professionals, which creates a lack of suitable illness-related education, and insufficient screening and preventative care (Hafeez et al., 2017). Inequities experienced in the clinical encounter contributes to the persistence of disparities. Lack of trust is then created from discrimination and biases experienced in the clinical encounter coupled with the historical context. It should no longer be acceptable to ignore inequities in the delivery of care (Baumann & Cabassa, 2020). Although Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination in healthcare facilities, the legislation has rarely been implemented aggressively (Fauci, 2001; Feagin & Bennefield, 2014).

Health and health care disparities not only undermine the health of the groups experiencing them, but also limit improvements in the quality of care for the general population which results in unwarranted costs (Ndugga & Artiga, 2021). Therefore, strategies to improve healthcare delivery to eliminate disparities must be a priority for the nation. Despite challenges that may occur, transforming policies and systems which created barriers for vulnerable populations to receive optimal health is crucial. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation examines five key questions and answers around disparities in health and healthcare: Disparities in Health and Health Care: 5 Key Questions and Answers | KFF

Current Efforts to Address Health and Healthcare Disparities

Equity has been designated as a priority, and the federal government has launched several initiatives and programs in response. These programs are focused on populations considered vulnerable in receiving care -BIPOC, residents of rural and inner-city regions, lower SES individuals, women, children/adolescents, and individuals with special needs.

Ndugga and Artiga (2021, para. 13 – 17) discuss current initiatives focusing on disparities in the healthcare system:

Office of Minority Health (HHS) – priorities include

-

Assisting states, territories, and tribes in creating and sustaining policies, initiatives, and practices that promote health equity

-

Increasing the use of community health professionals to meet the health and social services of BIPOC

-

Strengthening the cultural congruence of healthcare practitioners.

Racism declared a serious threat to public Health (CDC) – released April 2021, to lead endeavors in addressing intergenerational injustices caused by policies and practices that have resulted in inequities.

Maternal health initiatives:

-

President Biden issued a proclamation emphasizing the significance of tackling the high rates of maternal death and morbidity among Black/African American women

-

Extending the Medicaid postpartum coverage period

-

Allocating funding ($12 million) to the Rural Maternal and Obstetrics Management Strategies Program.

UNITE Initiative (National Institutes of Health) – commenced in March 2021, to address structural racism and racial inequities in biomedical research.

American Rescue Plan Act – enacted in March 2021, for funding (HHS invested $10 billion) to support vaccination and public health efforts, increasing access to health coverage, restoring funding for navigators to assist eligible people in enrolling, and health coverage affordability including measuresthat provide incentives for Medicaid Expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

Executive Order: Ensuring an Equitable Pandemic Response and Recovery – issued January 2021 to address the disproportionate and burdensome impact of COVID-19 on BIPOC, low SES, rural and other underserved populations. The order mandates

- The taskforce to strengthen equitable data collection, analysis, and allocation of resources

- HHS to conduct community outreach centered on vaccine confidence.

Executive Order: Restoring Faith in Our Legal Immigration Systems and Strengthening Integration and Inclusion Efforts for New Americans – issued January 2021 to undo regulations that hampered access to benefits including access to healthcare for immigrant families.

Executive Order: Strengthening Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act – issued January 2021 to direct federal agencies to ensure policies and procedures support access to health coverage, and establish a special Open Enrollment Period for Marketplaces.

Healthy People 2030

The vision of Healthy People 2030 | health.gov is focused on health equity, and has 5 objectives: 1) attain healthy, thriving lives and well- being free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death; 2) eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all; 3) create social, physical, and economic

environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and well-being for all; 4) promote healthy development, healthy behaviors, and well-being across all life stages; 5) engage leadership, key constituents, and the public across multiple sectors to take action and design policies that improve the health and well-being of all (ODPHP, n.d.a, para. 5). The initiative includes 355 objectives and has 12 leading health indicators: access to health services, clinical preventative services, environmental quality, injury and violence, maternal infant and child health, mental health, nutrition physical activity and obesity, oral health, reproductive and sexual health, social determinants of health, substance use, and tobacco.

In addition to the federal government, states, local communities, private groups, and practitioners also are involved in efforts to reduce health disparities (Ndugga & Artiga, 2021). A concerted effort with a variety of measures will be needed to tackle this issue. Other industrialized nations with healthcare systems not linked to race/ethnicity and SES have less disparities in comparison to the US (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014). The US needs to take note of the paradigm shift of the health care systems of Canada and European countries that had beneficial universal effects (Feagin & Bennefield, 2014).

Additional Strategies to reduce and/or eliminate disparities

A multidimensional approach must be utilized to address the multiple layers which contribute to health and healthcare disparities. Palmer et al. (2019) note efforts should focus on “upstream” social determinants of health. Prioritizing research on the consequences of governance and policy which create “downstream” impediments that limit the ability for vulnerable populations to receive optimal health (Palmer et al., 2019). Investing in social determinants of health, which provides individuals with resources to make healthy decisions, and has far-reaching health implications. Translating this to practice is a daunting task, but a necessary endeavor regardless of challenges. Focusing on:

- Removing poverty-inducing political arrangements that disproportionately favor the interests of the wealthy, contributing to rising income and health disparities (Khullar & Chokshi, 2018; WHO, 2008)

- Increasing policies that promote economic fairness (Khullar & Chokshi, 2018; WHO, 2008)

- Ensuring that as many people as possible have access to health insurance (WHO, 2000)

- Improving the standard of living (WHO, 2008)

- Improving healthcare delivery to foster equitable care

- Measuring and understanding the problem and assessing the impact of action (WHO, 2008, p. 32)

- Taking steps to expand programs and/or insurance coverage to immigrants (KFF, 2022)

Each of these are complex and will require a multifaceted strategy. For instance, focusing on improving healthcare delivery to foster equitable care can result in several initiatives, not limited to 1) requiring senior level administrators to incorporate diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in organizations’ strategic plans, 2) increasing initiatives and educational trainings for the current workforce on SDOH and caring for diverse populations, 3) incorporating social determinants of health and disparities in health/medical curriculums for the future workforce, 4) building patient’s trust and confidence in the health system, 5) developing a culturally congruent workforce, and 6) increasing workforce diversity.

The impact of having a Diverse and Culturally Congruent Workforce

As the US becomes a more diverse nation, it is critical to increase BIPOC representation in the healthcare workforce to adapt to the population. It is vital to recognize the problems with diversity in the healthcare system, and then take steps to enhance diversity through application and action. To improve diversity in the health professions, organizations must provide a foundation to support policies, trainings, and initiatives. Despite the fact that health systems and organizations have vowed to improve diversity, equality, and inclusion (DEI) over time, overall efforts have lagged behind the changing population picture (Pedulla, 2020). According to the most recent workforce report, BIPOC are especially underrepresented in the Health Diagnosis and Treating Practitioners Occupations category in comparison to White individuals who comprise a range from 67 – 86% (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2017). Diversification enhances access to services for vulnerable people, promotes cultural congruence, and benefits the healthcare system as a whole. Betancourt et al. articulated it best, “A healthcare workforce that reflects our nation’s increasingly diverse population will be vital if we are to deliver high-quality care to all” (2013, p. 903). Having a diverse and culturally congruent healthcare workforce is a necessity to dismantle racial and ethnic disparities, and to improve health equity. Building trust with patients and the community requires a workforce that is culturally congruent and diverse. Fostering trust and confidence in the clinical encounter is an essential component of any endeavor to reduce health disparities and provide high-quality care (Betancourt et al., 2013). Developing interpersonal skills for patient interactions during the clinical encounter is imperative (Richardson et al., 2012). Practitioners tend to employ verbal dominance and spend less time forming relationships with Black African/American patients in comparison to White patients (Johnson et al., 2004; Richardson et al., 2012). Quality interactions with patients is fundamental to providing patient- centered care. An organizational culture that epitomizes, respects, and embraces one’s cultural beliefs, language, values, and background in patient-centered care is considered culturally congruent (Cohen et al., 2002; IOM, 2004, p. 29). The impact of culture on one’s health experience, treatment adherence, and health outcomes is critical for administrators, practitioners, and support personnel to grasp (Cohen et al., 2002). Refer to the Cultural Competence chapter for more information on this.

In order to eradicate structural drivers of health and healthcare disparities, it is crucial to improve the circumstances of social determinants of health and address the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources (WHO, 2008). Acknowledging the past, and overcoming the resistance to change, to ensure all populations can benefit and receive optimal health. Disparities in health and health care must be addressed not just for social justice and equity’s sake, but also for the country’s general health and economic development (Ndugga & Artiga, 2021).

Conclusion

The challenges and barriers which exist for certain populations to access, utilize and receive optimal healthcare is disheartening. The gaps indicate that significant systemic efforts must be a priority to address these issues. A concerted effort will be needed to move the spectrum from reality to equity to justice, to be able to fully address health disparities. Although challenges will arise, it is essential to focus on solutions. Disparities in health pose ethical dilemmas which creates obstacles to improve the overall health of the nation. Although meaningful progress has been made overtime, continuing systems that were put in place to serve the “majority” will continue to lead to injustice, preventable morbidities and mortalities, and denial of basic rights to health (WHO, 2000, para. 4). Realigning and restructurings systems (healthcare and those outside of healthcare) is crucial to address health status and social determinants of health. “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” ~Audre Lorde.

Knowledge Check

Health inequities are most common in low- and middle-income countries. (True/False)

A white American will live about 3.5 years longer than a Black American born on the same day. (True/False)

The gap between white American and Black American infant mortality rates has only improved slightly in the past 50 years. (True/False)

Whether or not you have health insurance is the best predictor of your health. (True/False)

Wealthy women are 20 times more likely to have a birth attended by a skilled health worker than poor women. (True/False)

Most deaths from noncommunicable diseases like heart disease and diabetes occur in high-income countries. (True/False)

Answers:

False. Health inequities are most common in low- and middle-income countries. Inequities exist globally, affecting people in every country. In the U.S., Black Americans, who constitute 13% of the population, bear almost half of all new HIV infections.

True. A white American will live about 3.5 years longer than a Black American born on the same day.

True. The gap between white American and Black American infant mortality rates has only improved slightly in the past 50 years.

False. Whether or not you have health insurance is not the sole predictor of your health; other factors play crucial roles.

True. Wealthy women are indeed more likely to have skilled health workers attend their births compared to poor women.

True. Most deaths from noncommunicable diseases occur in high-income countries.

Key Words

BIPOC: Black, Indigenous, and people of color.

Cultural congruence: a process of continually acquiring the necessary knowledge and skills to provide high-quality services to persons of many cultural and ethnic backgrounds.

Diversity: inclusion of people from various backgrounds. Ability, age, cultural background, gender identity, language, race/ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic level are all examples of diversity.

Health care disparity: differences in insurance coverage, quality of care, access, and utilization between groups.

Health disparity: when one group experiences a higher burden of illness, injury, disability, violence, or mortality than another.

Health equity: every person having the opportunity to obtain their highest level of health.

Implicit biases: unconscious attitudes and behaviors towards an individual based on stereotypes associated with categories such as race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, socio-economic status.

Infant mortality rate: the death of an infant before their first birthday per 1,000 live births.

LGBTQ+: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning or queer.

Maternal mortality rate: the death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy per 100,000 live births.

Prejudice: a preconceived feeling or opinion about a person based on personal characteristics.

Racism: conditions -policies, practices, systems, and norms- that give value and privilege to some people, and results in conditions that disadvantage others based on the color of their skin

Residential segregation: separating two or more populations into different neighborhoods, influencing their living environments

Social determinants of health: the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.

Socioeconomic status: measure of social position of an individual or group, with emphasis on income, occupation, and education.

Stereotypes: a generalized belief about a group of people.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2022, January). 2021 national healthcare quality and disparities report. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr21/ index.html

Ailshire, J., & Garcia, C. (2018). Unequal places: The impacts ofsocioeconomic and race/ethnic differences in neighborhoods. Journal of the American Society on Aging, 42(2)20-27.

Altman, D. (2021, August 02). The health system appears to be selling lgbt+ people short. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/ perspective/the-health-system-appears-to-be-selling-lgbt- people-short/

Artiga, S., Pham, O., Orgera, K., & Ranji, U. (2021, November 10). Racial disparities in maternal and infant health: An overview. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/ report-section/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant- health-an-overview-issue-brief/

Barr, D. A. (2019). Health disparities in the United States: Social class, race, ethnicity, and the social determinants of health. (3rd ed.). John Hopkins University Press

Baumann A. A., & Cabassa, L. J. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research, 20(190), 1-9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3

Betancourt, J. R., Beiter, S., & Landry, A. (2013). Improving quality, achieving equity, and increasing diversity in healthcare: The future is now. Journal of Best Practices in Health Professions, 6(1), 903-917.

Black, S., Blount, L., Brown, S. & Frakt, A. (2020, August 5). Confronting structural racism in Health Services Research [Plenary panel]. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, Virtual.

Brottman, M. R., Char, D. M., Hattori, R. A., Heeb, R., & Taff,S. D. (2020). Toward cultural competency in health care: A scoping review of the diversity and inclusion in education literature. Academic Medicine, 95(5), 803-813.

Carnethon, M. R., Pu, J., Howard, G., Albert, M. A., Anderson,

C. A. M., Bertoni, A. G., Mujahid, M. S., Palaniappan, L., Taylor,

H. A., Willis, M., & Yancy, C. W. (2017). Cardiovascular health in African Americans: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 136(21),e393–e423.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, August 2). About rural health. https://www.cdc.gov/ruralhealth/ about.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a, September 5). Racial and ethnic disparities continue in pregnancy-related deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial- ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b, December 20).HealthdisparitiesamongLGBTQyouth. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/disparities/health- disparities-among-lgbtq-youth.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a, April 22). The Tuskegee timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/ timeline.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b, August 9). HIV in the United States and Dependent Areas. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021c, September 8). Infant mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/ maternalinfanthealth/infantmortality.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021d, November 24). Racism and health. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/ racism-disparities/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 1). Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/ covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by- race-ethnicity.html

Chang, C. D. (2019). Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Healthcare, 49(1), 23-30.

Chowkwanyun, M. (2011). The strange disappearance of history from racial health disparities research. Du Bois Review, 8(1), 253-270. doi:10.10170S1742058X11000142

Cohen, J. J., Gabriel, B. A. & Terrell, C. (2002). The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Affairs, 21(5), 90-102.

Collins, P. H. (2015) Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 1–20.

Fauci, C. A. (2001). Racism and healthcare in America: Legal responses to racial disparities in the allocation of kidneys. Boston College Third World Law Journal, 21(1), 35-68.

Feagin J., & Bennefield, Z. (2014). Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Social Science and Medicine, 103, 7-14. doi: 10.1016/ j.socscimed.2013.09.006

FitzGerald, C., & Hurst, S. (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BioMed Central Medical Ethics, 18(19), 1-18. doi 10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

Frey, W. H. (2018, March 14). The US will become ‘minority white’ in 2045, Census projects. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/03/14/the- us-will-become-minority-white-in-2045-census-projects/

Hafeez, H., Zeshan, M., Tahir, M. A., Jahan, N., & Naveed, S. (2017). Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: A literature review. Cureus, 9(4), e1184-1190.

Indian Health Services. (2019). Indian health disparities. https://www.ihs.gov/sites/newsroom/themes/responsive2017/ display_objects/documents/factsheets/Disparities.pdf

Institute of Medicine. (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. National Academy Press. doi: 10.17226/12875

Institute of Medicine. (2004). In the nation’s compelling interest: Ensuring diversity in the health care workforce. National Academy Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK216009/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK216009.pdf

Jaret, P. (2020, February 3). Attracting the next generation of physicians to rural medicine. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/attracting- next-generation-physicians-rural-medicine Johnson, R. L., Roter, D., Powe, N. R., & Cooper, L. A. (2004). Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. American Journal of Public Health. 94(12):2084–90

Jones, C. P., Holden, K. B., & Belton, A. (2019). Strategies for achieving health equity: Concern about the whole plus concern about the hole. Ethnicity & Disease, 29(Suppl 2), 345-348.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2021, June 7). The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States: The basics. https://www.kff.org/ hivaids/fact-sheet/the-hivaids-epidemic-in-the-united-states- the-basics/

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2022, April 6). Health coverage of immigrants. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health- policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/

Khullar, D., & Chokshi, D. A. (2018, October 4). Health, income, poverty: Where we are and what could health. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.901935/

Krahn, G. L., Walker, D. K., & Correa-De-Araujo, R. (2015). Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. American Journal of Public Health. 105(S2), S198-206. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182

Lynch, S. (2020, June 19). Fact check: Father of modern gynecology performed experiments on enslaved Black women. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/ 2020/06/19/fact-check-j-marion-sims-did-medical-

experiments-black-female-slaves/3202541001/

National Center for Health Statistics (2021, August). Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the national health interview survey, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur202108-508.pdf

Ndugga, N., & Artiga, S. (2021, May 11). Disparities in health and health care: 5 key questions and answers. Kaiser Family Foundation.https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health- policy/issue-brief/disparities-in-health-and-health-care-5-key- question-and-answers/

Novak, N. L., & Lira, N. (2018, March 22). California once targeted Latinas for forced sterilization. Smithonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/california-targeted- latinas-forced-sterilization-180968567/

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.a). Healthy people 2030 framework. https://health.gov/ healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.b). Poverty. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/ social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/poverty

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.c). Social determinants of health. https://health.gov/ healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2022, February 6). Disparities. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/ about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities

Office of Minority Health (2021, October 12). Minority population profiles. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/ browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=26

Pacheco, C. M., Daley, S. M., Brown, T., Filippi, M., Greiner, K. A., & Daley. C. M. (2013). Moving forward: Breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2152-2159. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301480

Palmer, R. C., Ismond, D., Rodriquez, E. J., & Kaufman, J. S. (2019). Social determinants of health: Future directions for health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 109(51)S70-S71.

Pedulla, D. (2020). Diversity and inclusion efforts that really work. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/05/ diversity-and-inclusion-efforts-that-really-work

Placide, V. & Vance, M. (2021). Supporting diversity and inclusiveness amid a changing academic landscape. In C. Ford & K. Gaza (Eds.), Updating and innovating health professions education: Post-pandemic perspectives. IGI Global.

Richardson, A., Allen, J. A., Xiao, H., & Vallone, D. (2012). Effects of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on health information-seeking, confidence, and trust. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 23(4), 1477-1493.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2014, June). Reducing disparities to improve the quality of care for racial and ethnic minorities. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2014/06/ reducing-disparities-to-improve-care-for-racial-and-ethnic- minorities.html

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation & University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. (2020, March). 2020 county health rankings key findings report.https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/reports/2020-county-health-rankings-key-findings-report

Roberts, M., Reither, E. N., & Lim, S. (2020). Contributors to the black-white life expectancy gap in Washington, D.C. Scientific Reports, 10(13416), 1-12.

Rosen, G. (1973). Health, history, and the social sciences. From medical police to social medicine: Essays on the history of health care (G. Rosen, Ed.). Science History Publications.

Sagynbekov, K. (2017, October). Gender-based health disparities: A state-level study of the American adult population.https://milkeninstitute.org/sites/default/files/ reports-pdf/103017-Gender-BasedHealthDisparities_0.pdf

Schnierle, J., Christian-Brathwaite, N., & Louisias, M. (2019). Implicit bias: What every pediatrician should about the effect of bias on health and future directions. Current Problems in Pediatric Adolescent Health Care, 49, 34-44.

Shertzer, A., Twinam, T., & Walsh, R. P. (2016). Race, ethnicity, and discriminatory zoning. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8(3)217-246.

Shi, L., & Singh D. A. (2017). Delivering health care in America (7th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Siegel, J., Coleman, D. L., & James, T. (2018). Integrating social determinants of health into graduate medical education: A call for action. Academic Medicine, 93(2), 159-162.

Stephens, M. (2002). The treatment: The story of those who died in the Cincinnati radiation tests. Duke University Press.

Thorpe, K. E., Chin, K. K., Cruz, Y., Innocent, M. A., & Singh. (2017, August 17, 2017). The United States can reduce socioeconomic disparities by focusing on chronic diseases. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/ forefront.20170817.061561/full/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. (2017). Sex, race, and ethnic diversityofU.S.,healthoccupations(2011-2015). https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health- workforce/data-research/diversity-us-health- occupations.pdfhttps://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/ nchwa/diversityushealthoccupations.pdf

Wallace, S. P., Torres, J. M., Nobari, T. Z., & Pourat, N. (2013 August). Undocumented and uninsured: Barriers to affordable care for immigrant populations. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research&CommonwealthFund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/ documents/media_files_publications_fund_report_2013_au g_1699_wallace_undocumented_uninsured_barriers_immigra nts_v2.pdf

Walston, S. L., & Johnson, K. L. (2021). Healthcare in the United States. Health Administration Press.

Washington, H. A. (2007). Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. Harlem Moon

Wilbur, K., Snyder, C., Essary, A. C., Reddy, S., Will, K. K., & Saxon, M. (2020). Developing workforce diversity in the health professions: A social justice perspective. Health Professions Education, 6, 222-229.

Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., Davis, B. A., & Vu, C. (2019). Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Services Research, 54(6), 1374-1388.

World Health Organization. (2000, February 7). World Health Organizationassessestheworld’shealthsystems. https://www.who.int/news/item/07-02-2000-world-health- organization-assesses-the-world’s-health-systems

World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Report from the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/ finalreport/en/index.html

Yale Medicine Magazine. (2012). Eliminating health disparities. https://medicine.yale.edu/news/yale-medicine-magazine/ article/eliminating-health-disparities/