13

US Health Policy

Raymond Higbea, PhD, FACHE, FHFMA

Lara Jaskiewicz, PhD, MPH, MBA

Greg Cline, PhD

Grand Valley State University

“The obligation of the government to protect the public health, safety, morals, and general welfare” – Allan Wolf

Learning Objectives

- Understand the history of health policy in the US

- Describe the US policy making process

- Explain how to influence the US policy process

Introduction

In the US, health policy is reactionary – meaning it is developed in response to identified problems. Yet, many changes in the US healthcare system today are driven by health policy. This chapter begins with a historical overview of health policy in the United States that provides context for the subsequent sections of the health policy discussion. Next, is a detailed discussion of the policy process from development through implementation and evaluation. Following this section is a short discussion of the role of intergovernmental tensions and how to conduct policy advocacy.

History

Health policy in the United States has relatively thin historic roots with any substantive activity beginning about 100 years ago, and a significant uptick in activity beginning the latter half of the 20th century which continued into the 21st century. Early health policy was generally promulgated by the states which performed quarantines of infectious diseases such as smallpox and yellow fever. The general focus of US health policy over time has been on increasing access to services and on shaping payment modalities.

The first national health policy was the Sailors and Mariners Act of 1798, that expanded the common practice of providing resources to care for mariners who were ill and away from home. For instance, in 1658 a shipping company established New York’s Bellevue Hospital – considered by many to be the oldest hospital in the United States – to provide care for mariners who were ill and away from their home ports. The purpose of the 1798 federal policy was to build upon the earlier action by the shipping company and fit into the categories of providing access to medical services coupled with a payment mechanism. This coupling of access and payment in the Sailors and Mariners Act set a precedent for medical and healthcare legislation that, with the exception of licensing laws introduced in the mid-1800s, was dormant until the early 1900s.

During these years of dormancy, the quality of medical training for physicians and delivery of care by physicians and hospitals increased dramatically. One characteristic of this period was the struggle of allopathic physicians to solidify their position as quality providers of medical care in a field full of options such as osteopathic, chiropractic, and naturopathic physicians. The most decisive move to solidify the position of allopathic physicians as “true” physicians occurred during the 1876 American Medical Association (AMA) annual meeting where the AMA Ethics committee called out the need for licensure of physicians to ensure the quality-of-care delivery and economic viability of its members. States followed suit by reestablishing licensing laws that had been in place prior to the Civil war and relaxed during the war. This occurred under the guidance of local public health officials during the 1880s.

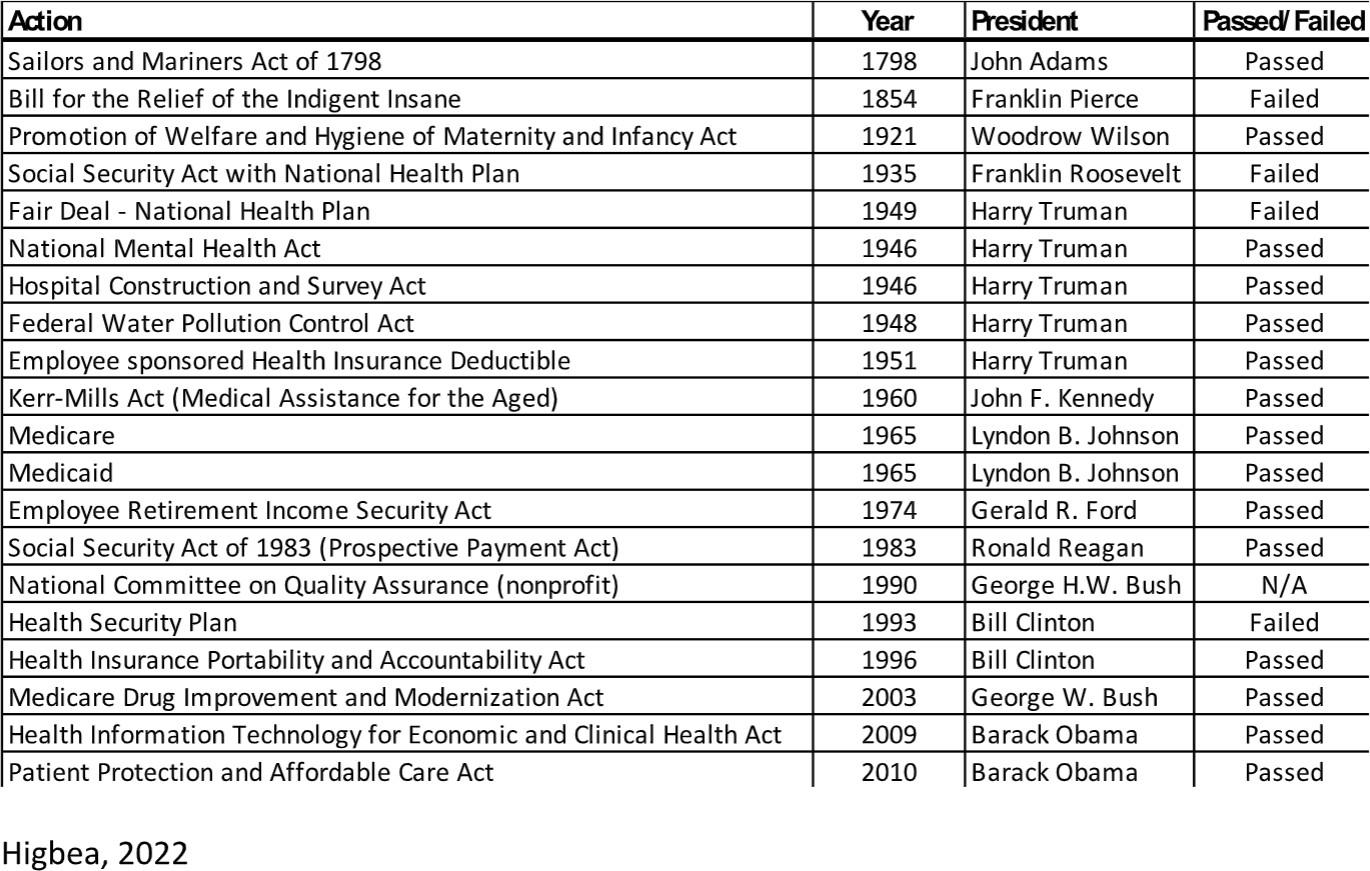

The general trend (Table 1) for federal healthcare legislation over the 20th and 21st centuries is the failure of attempts to provide national healthcare services and the success of incremental legislation providing access to and payment for healthcare services focused on specific population subgroups. Throughout this period, the United States developed strong incentives for employers to provide healthcare insurance for their employees (Employee sponsored health insurance deductible – 1951) with the percentage of individuals covered by employer sponsored plans ranging from approximately 72% in the 1970s (Social Security Administration, 1972) to a low of 56% in the 2010s (Peterson KKF, 2022) then moving slightly down to 54% in 2020 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). In comparison, the portion of individuals covered by government health insurance programs have grown from 33% between 1970 and 1990 to 40% during the 2000s (Congressional Research Service, 2022). These increases in governmental coverage are all the results of healthcare policy actions to increase access to healthcare services while decreasing the financial barriers to them through government payment for services (see appendix – Health Reform Bills, Actions, & Presidents (2018) – Higbea). Additional legislation enacted in 1965 is the Older Americans Act (PL 89-73, 79 Stat.218) that at the time did not seem pertinent to health; however, in light of the current focus on the social determinants of health is very pertinent. The Older Americans Act focuses on nutrition and other home-based social supports that directly affect health. This bill has continuously had bipartisan support and most recently been updated on several occasions most recently as the Supporting Older Americans Act of 2020 (PL 116-258). There are several federal and state agencies involved in the implementation of this act with the most recognizable being local Area Agencies on Aging

Table 1

Major U.S. Health Legislation

One unique aspect of private trends resulting in government policy actions has been concerns about the quality of healthcare services. During the 1990s, there was an outcry from corporate leaders about the rapidly increasing cost of healthcare services with a correlated lack of quality. One result of this concern was the development of private groups focused on grading the quality of healthcare services. On the government side this led to a series of actions including the initiation of quality pay for performance plans; the establishment of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Medicaid 1115 waivers to test linking quality to cost, outcomes, and payment; and establishment in the Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act of the CMS Innovation Center.

Inclusion of quality into the milieu of health policy foci that to this point had focused on access and payment resulted in an access-payment-quality triangular paradigm (Higbea & Cline, 2021). In this paradigm, all three characteristics play equal parts, resulting in an equilateral triangle. When any of the sides are unbalanced, the triangle is no longer equilateral and depicts an unbalanced delivery model that needs to be rebalanced by private or public leaders. When these imbalances are addressed by public leaders, they result in health policy actions that can range from legislation, administrative rules and regulations, or judicial rulings.

Policy Process

The policy process begins by defining a public problem. When problems arise in the public arena, they are debated and defined by private and public leaders. As this debate matures, the problem definition becomes more refined and potential solutions begin to emerge. In the American policy process, implementation of solutions frequently begins in the private sector then shifts to the public sector if private solutions fail or are deemed inadequate. During the problem definition to solutions debate, the political philosophy of the actors is reflected in their proposed solutions. Throughout the history of the United States, we have had factions favoring strong central government and factions favoring weak central government. Another way to frame these differences is by the focus on positive liberty (the ability to attain something previously denied), often aligned with the strong central government faction, or negative liberty (the ability to engage in activities without interference), often aligned with the weak central government faction.

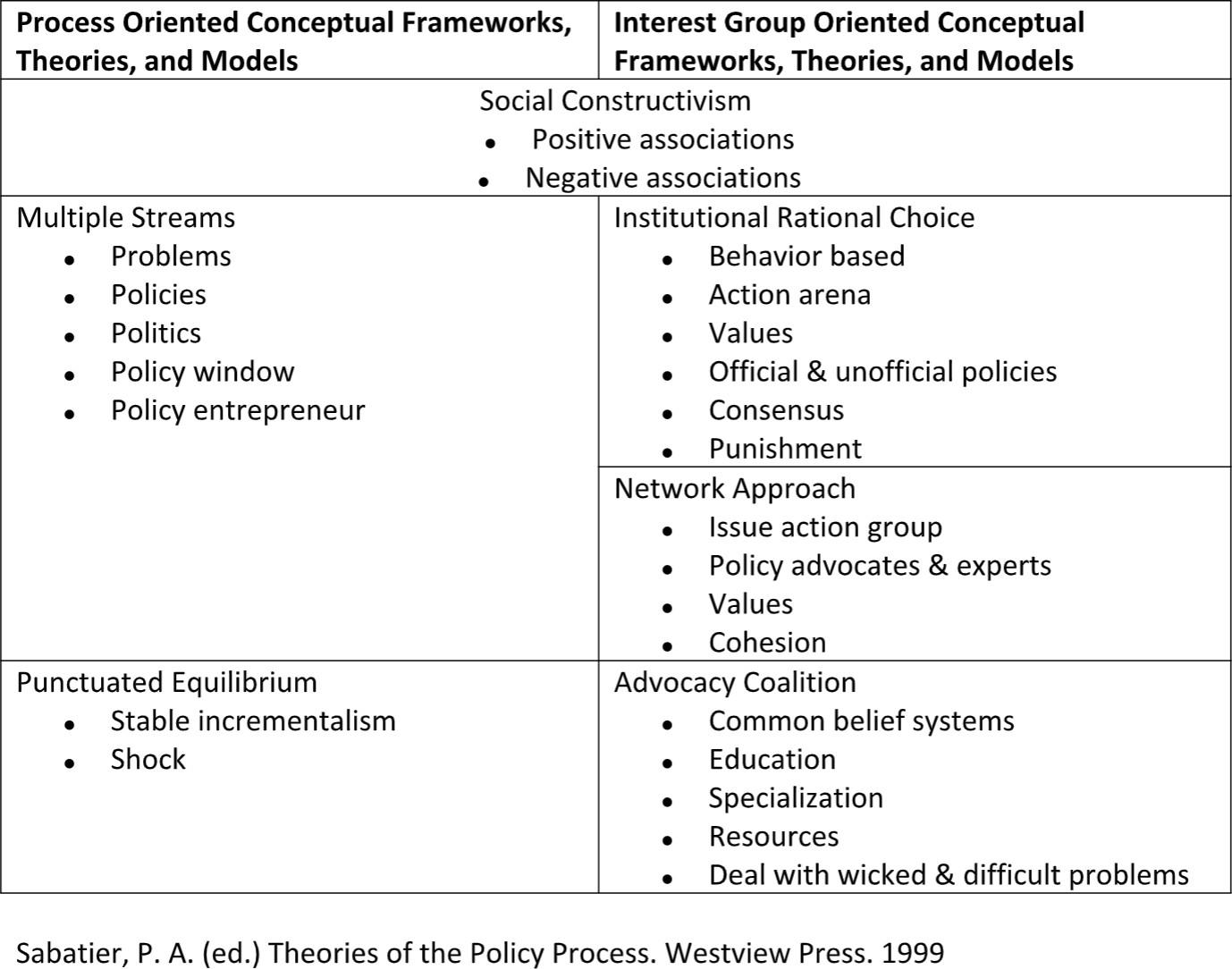

Table 2

Interest Group Frameworks, Theories, and Model Characteristics

Throughout the problem definition and solutions generating process several policy development theories interact (see table 2). Social construction theory describes how we define the individuals and groups affected by the policy problem then craft a policy solution based upon our definition. Once this is completed the problem comes under influence of process and interest group theories. Process theories describe the journey problems take from initial germination of the problem or idea to signing legislation into law to the implementation and modification of a law. These theories discuss how incrementalism is the normal policy process that includes a shock which frequently results in legislative activity and, potentially, a new or updated law (figure 1). The average time from germination of an idea to signed legislation is 20 years, with a range of 10 to 60 years. Complimentarily, interest group theories describe how individuals and organizations interact with public and private leaders to develop problem definitions and policy solutions. Finally, while all these theories can be studied extensively for their individual characteristics and merits, in reality they are all working at the same time in the policy or action arena.

Figure 1

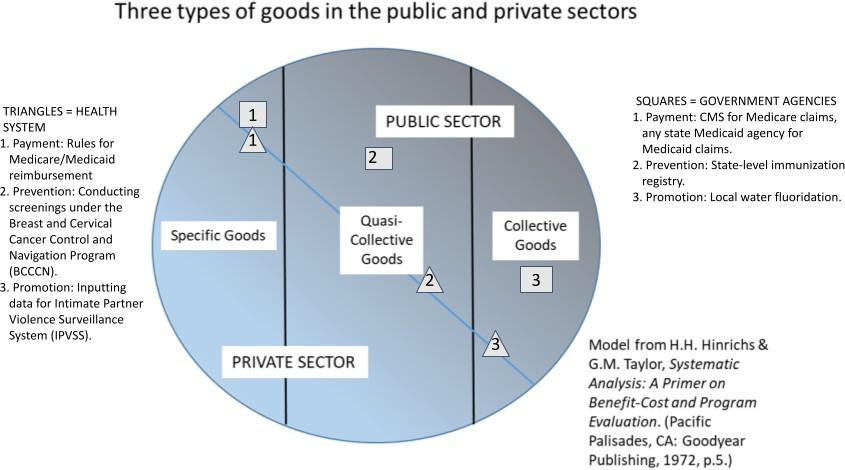

Health Policy, Three Types of Goods in the Public and Private Sectors

Higbea, R.J. & Cline, G.A. (2021) Government and Policy for U.S. Health Leaders. Jones & Bartlett Learning

Another way to describe the above actions is through public choice theory which takes the above policy theories and combines their effect with economic theories and voter choice. This theory categorizes policy outputs (goods and services) as specific, quasi-collective or collective goods (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

The Multi-attribute Problem: Propositions

Higbea, R.J. & Cline, G.A. (2021) Government and Policy for U.S. Health Leaders. Jones & Bartlett Learning

Essentially, these categories describe who the payers are and who has access to the goods. Voter choice is brought into this mix when candidates for public office align themselves with a policy solution (goods or services) aligned with the voter’s values, political philosophy, and perceived societal welfare.

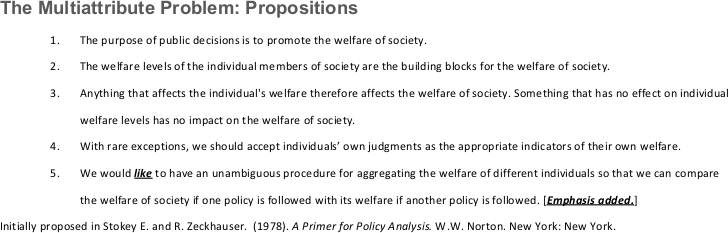

It is also important to consider multi-attribute problems, a phenomenon that recognizes that all public policy has multiple goals (see Figure 3). Rarely do these goals all align with voter preference thus voters choose the policy approach that either does the most good or least bad.

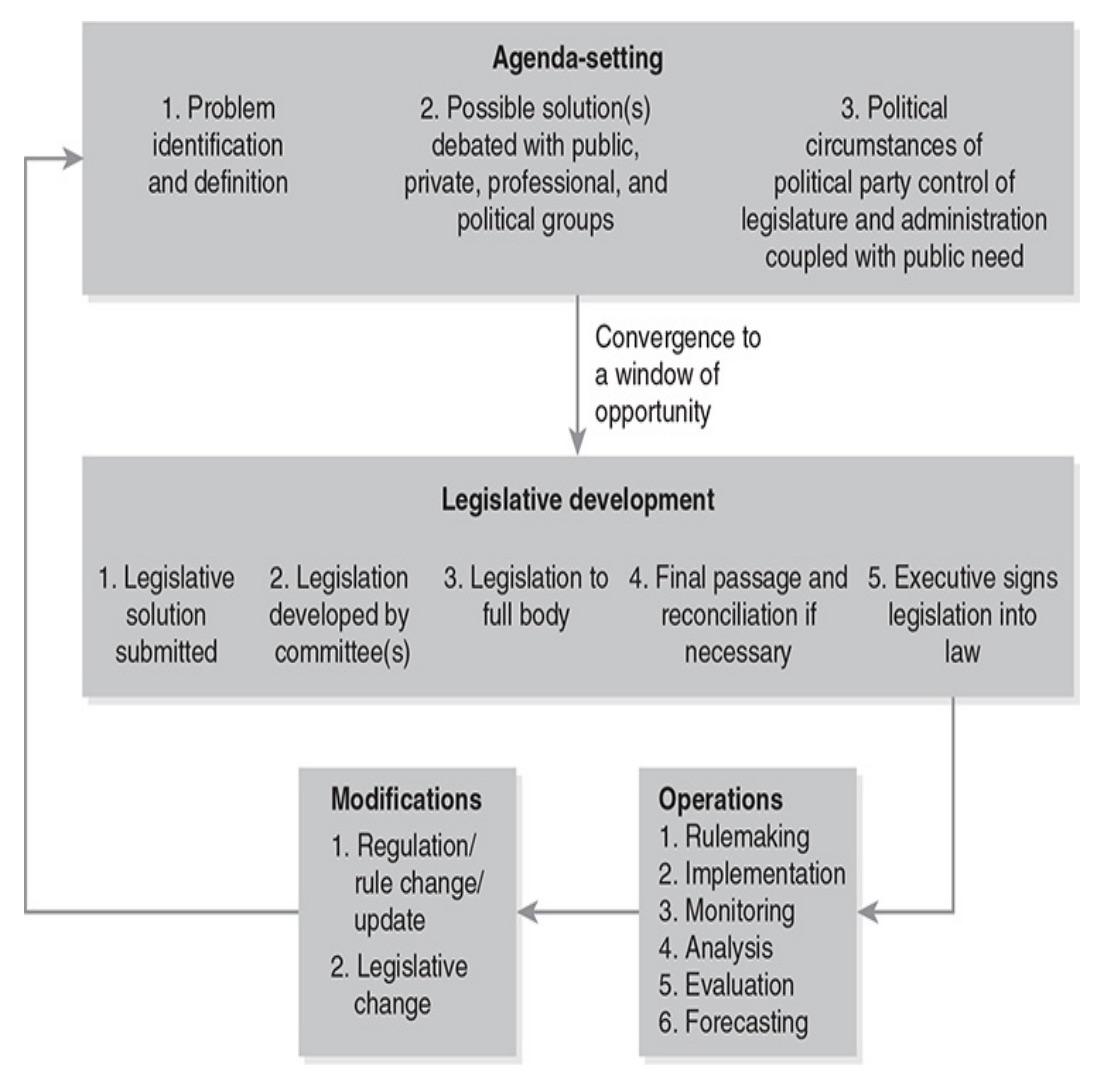

The policy process model is rather straightforward (figure 3) however, one should not be deceived by the flatness of the model, and it is important to understand that the policy process is dynamic, with policies constantly under review and revision. There are four categories of actions in the policy process: agenda setting, legislative action, operations, and modifications.

Figure 3

The Policy Process Model

Higbea, R.J. & Cline, G.A. (2021) Government and Policy for U.S. Health Leaders. Jones & Bartlett Learning

Agenda setting is the initial and longest phase of the policy process. During this phase the policy problem is debated and defined; potential solutions emerge, frequently aligned with political philosophy; policy entrepreneurs emerge to champion and shepherd the policy solutions through the legislative process; and the political circumstances align to include political party legislative majority with an executive from the same party and an event or shock (natural or generated) that brings the political problem to public attention (window of opportunity). Phase two is the legislative process where the problem is addressed through legislative hearings; legislative language is developed, economically scored, and voted upon; and once passed by both legislative chambers, is signed into law or vetoed by the executive. Phase three is operations, including rulemaking, implementation, monitoring, analysis, evaluation, and forecasting. All operations phase activities occur in the executive branch with each subphase requiring an extensive amount of planning, review, and public interaction. Finally, modification is the last phase where the work outputsof operations (monitoring, analysis, evaluation, and forecasting) are used to inform needed regulatory or legislative changes and thus start the process over again with a series of agenda setting activities seeking to influence any regulatory or legislative changes.

Agenda Setting

Agenda setting is the longest of the phases of the policy process lasting for an average of 20 years with a range of 10 years to 60 years. Problem identification and definition is the first aspect of this phase that includes identification and definition of a public or societal problem. These problems are identified by media reports, community and organizational discussions, professional deliberations, and political activity. Once a problem has been identified, it is then defined by written and verbal debates and reports through the organizations listed in the previous sentence. As this process matures the definition and initial potential solutions begin to take on the political philosophy of the organization or individuals proposing the definition and potential solutions. Frequently, the private sector will attempt to implement the potential solutions that are most beneficial to their constituents and their organization(s) in an effort to forestall legislation with rigid requirements. If private attempts fail or are deemed inadequate, the solution moves to the public sector. Throughout this phase, private and public spokespersons or policy entrepreneurs emerge who become the champions of the problem and its potential solutions, author the private or legislative proposal, and shepherd the solutions through the legislative development process.

Legislative Development

The legislative development process commences upon convergence of the window of opportunity, described later in this section. Frequently, policy entrepreneurs have proposed legislative language drafted – often in collaboration with interest groups aligned with the entrepreneur’s political philosophy. The statistics on legislation per US Congress (2-year cycle) show a mean of 12,000 bills submitted and only 340 enacted; just 3% of the bills submitted are passed. A large part of the rationale for all of these submissions is policy entrepreneurs waiting in line for the window of opportunity to converge upon their policy issue and legislation. Another reality policy entrepreneurs understand is if their bill is chosen as the basis or template for addressing a public problem, their proposed legislation will be altered, sometimes drastically. However, since they are the primary author(s) the policy entrepreneurs will be in a strong position for negotiating and sometimes lead the negotiations of the final legislation.

Once a proposed legislation (bill) is submitted, the leader of the chamber chooses whether to move the legislation forward or not address the concern. If the legislation moves forward, the legislation is assigned to the committee or committees that have jurisdiction over the areas covered in the legislation. The committee chair then has the opportunity to move forward on the legislation or ignore it and allow it to die. When legislation moves forward, the committee actions include conducting hearings with interested parties and experts in agreement with and opposed to the legislation. On completion of the hearings, the committee votes whether to move forward with the legislation. If they choose to move forward, the legislation goes through markup where every word and line of the legislation is read and marked with votes taken on any changes throughout the process.

Once the markup process is complete, the legislation is scored by the Congressional Budget Office. Scoring is only for major legislation and provides legislators an indication of how the bill will affect the economy. It should be noted that there are two methods of economically scoring legislation. Static scoring is reserved for minor legislation and is narrow in scope, whereas dynamic scoring includes economic impacts to the general economy. After all of these elements are assembled, the committee votes on their final version of the legislation. If there is a majority of the committee in favor of the legislation, it is discharged from the committee to the full legislative body for consideration. However, if the majority of the committee is not in favor of the legislation, it does not move forward and is considered to have died in committee. Even when legislation dies in committee, there are rules and mechanisms that can be enacted to bring the legislation to the full chamber for debate and vote.

The next step for the legislation is consideration by the full legislative chamber where the chamber leader and leadership team map a course forward for the legislation. This map includes whipping up votes where the party whip goes member to member to discuss the legislation, hear their concerns, and ensure their vote. Once sufficient votes have been whipped, the chamber leader will work with the rules committee to set the rules for the debate and a date for the vote. During the legislative debate, members of the chamber have the opportunity to voice their support or concern and submit amendments to address serious concerns that need to be voted on separately. If the legislation passes, it moves to the other chamber provided the legislative chambers are organized a bicameral; otherwise, if the chamber is unicameral, it moves directly to the executive. If the legislation fails to garner sufficient votes it dies in the chamber and does not move forward. Even if legislation dies, it can be revived and voted on again after the concerns that caused it to die have been addressed. In the other chamber, assuming a bicameral system, the legislation goes through a similar process. If the legislation produced is identical to the legislation submitted by the other chamber and is voted on by enough votes to pass, the legislation moves to the executive. If the legislation is not identical, it goes to a conference committee made up of members from both chambers where the differences are resolved, and a final piece of legislation is resubmitted for vote by both chambers. However, if the conference committee is unable to resolve the differences, the legislation dies at the conference.

The final action on passed legislation resides with the executive. If the executive agrees with or supports the legislation and signs the bill, it becomes law. In recent decades, it has become a custom for executives to include a signing statement that either states why they agree with the legislation or why they are signing it even though they disagree with parts or all of the legislation. Oftentimes executives will host a signing ceremony for major legislative victories that includes a large media presence with constituents and legislative supporters. Legislation can also become law without the executive’s signature if 10 days have lapsed while Congress is in session. If, however, Congress is not in session for 10 days and the executive does not sign the legislation, it dies and does not become law. Finally, if the executive disagrees with the legislation, it may be vetoed and not become law. Frequently, vetoes result from political philosophical differences and may be overridden by a two-thirds vote by Congress.

Window of Opportunity

Forward movement from policy to signed law depends upon an opening up of the window of opportunity (figure 1). The window of opportunity opens when the problems, (proposed) policies, politics, policy window, and policy entrepreneur (the 5 Ps) are aligned with an accompanying artificial or natural shock. Problems, policies, and policy entrepreneurs have been discussed above. Political alignment occurs when the legislative and executive branches are aligned normally, meaning they are of the same political party and political philosophy. Public problems and public policy move in an incremental fashion until an artificial or natural event shocks the incremental process into action by opening the window of opportunity. Opening up of the policy window automatically triggers the legislative development process.

Operations

Once legislation is signed into law, it moves to the executive branch of government for six distinct sets of actions: rulemaking, implementation, monitoring, analysis, evaluation, and forecasting. Operations and modifications (the last step) ensure the dynamism as opposed to stasis of the policy process.

Rulemaking is the process of transforming law into implementable actions. The rulemaking process begins once legislation is signed into law and is the most prescribed of operations activities. For the roughly 150 years following the signing of our constitution, rulemaking was a rather loose and undisciplined process left up to the discretion of the department secretary whose area was affected. The steady stream of legislation produced under President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs heightened the need for a disciplined rulemaking process and resulted in passage of the Federal Register Act of 1935 (44 USC Chapter 15). During the following 45 years an additional 6 laws were passed providing direction for the rulemaking process with the most significant being the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946 (5 USC §551) that added predictability to agency decision making. From 1980 to the present the United States has added 32 administrative laws, executive orders, and presidential memoranda with the intent of increasing the structure and predictability of the administrative rules development process.

Once legislation is signed into law, the executive branch moves into the rulemaking process by assigning the appropriate agency(ies) responsibility for making rules defining how the policy will be implemented. The rulemaking process can be as complex as the legislative development process with agencies holding hearings, receiving testimony from constituents, and developing a set of rules that take either a textual or purposive approach depending upon the nature of the law. The textual approach looks to the text of the law for its interpretation which is often apparent such as a cost-of-living increase for Social Security. Whereas the purposive approach looks at the purpose of the law and by its nature needs to be interpreted such as decreasing the burden of environmental regulations or increasing access to fresh foods. Once the rules have been drafted, they are published in the Federal Register for a period of 30 -120 days depending upon the significance of the rules and policy implications. Citizens and organizations are encouraged to comment on the proposed rules with comments submitted by electronic means. Depending upon the significance of the law and proposed rules there may be as few as zero comments to as many as 100,000. The agency then reads and addresses the comments and then submits its final rules through the Federal Register along with an implementation date and plan.

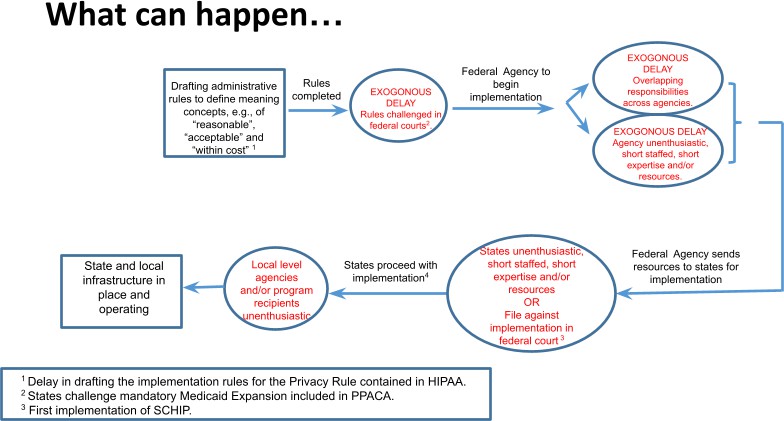

Implementation is the next major operations step where the rulemaking work is put into practice. Normally, the implementation process gives public and private organizations responsible for implementing the policy change sufficient time – up to one year – to make the administrative adjustments necessary for policy implementation. Undoubtedly, implementation tests a manager’s technical skill and political abilities. While there are a number of theories and techniques on policy implementation, they can be summarized: understanding the policy; understanding the targeted constituents; structuring the implementation to ensure constituent engagement; ensuring that everyone involved is committed to implementation success; and accounting for any undermining activities or structural barriers. One important phenomenon often missed by those focusing on implementation typology is the role of interagency and intergovernmental dynamics on policy implementation. In many ways, the dynamism of this situation parallels the dynamism of the window of opportunity in the legislative development process. When agencies and other levels of government (state and local) are aligned on the goals, political philosophy, and intended outcomes, the implementation normally runs relatively smoothly. However, if there is a lack of political alignment or enthusiasm, delays in the range of years or less than robust adherence to policy rules and regulations can stagnate or inhibit policy implementation – delays can be caused by court challenges to the policy (figure 5). Regardless of the reason, delays can move the implementation to the next operational step and fast forward them back into the agenda setting and legislative development process.

Figure 5

Health Policy: What Can Happen…

Higbea, R.J. & Cline, G.A. (2021) Government and Policy for U.S. Health Leaders. Jones & Bartlett Learning

Policy monitoring occurs at several public and private levels in both formal and informal forums. In the private sector monitoring occurs through informal constituent feedback and formal professional research and opinion publications. Public sector monitoring occurs through several governmental agencies, including the Congressional Budget Office, the Joint Committee on Taxation, the Congressional Research Service, the General Accountability Office, and the Office of Management and Budget. All of these agencies have formal charges to monitor the performance of public programs and to bring forth recommendations for modifications to the programs under their jurisdiction. Of course, the obvious reason programs are monitored is to ensure they are performing as desired yielding intended outcomes. Closely associated with monitoring are analysis, evaluation, and forecasting of data and programs moving progressively from analysis or gaining meaning from the qualitative or quantitative data, evaluation or determining whether or not the program is effective in meeting the policy goals and forecasting or anticipating how the program will perform in the future with or without changes.

When programs do not perform as desired or perform as desired but could perform better with some enhancements or modifications, the policy enters back into the agenda setting and legislative development process. If the program modifications are within the scope of the current law, modification can be enacted at the executive level through revisions to rules and regulations. However, if the desired program modifications are outside the scope of the current law, the revisions must be enacted through the legislative process. The breadth of the policy modifications enacted by the legislature is dependent upon the scope and breadth of the desired modification(s). For example, Medicare and Medicaid are not stand-alone laws, rather they are amendments to the Social Security Act of 1935 and are listed as Acts 18 and 19 respectively. These two laws (amendments) have been modified on multiple occasions with Medicare, since its inception in 1965, having 7,664 modification bills submitted with 281 enacted as law (3.67%) and Medicaid having 4961 modification bills submitted with 264 enacted as law (5.32%).

Intergovernmental Dynamics

Influencing the policy process begins with gaining an understanding of how federal and state governments interact and the differences among legislative chambers and branches of government. Once there is an understanding of these dynamics one can shift attention to how organizations and individuals can influence these branches of government. The dynamic of how states work with the federal government is rooted in federalism with states. The 10th amendment states:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

If there is one word that describes the dynamic of the 10th amendment it is tension. Tension about how much the federal government can force the states to perform to the desired will of federal leaders. Tension from and among the states about how much power they hold to shape policy for their citizenry and how much encroachment of power from the federal government should be tolerated. An example of this tension is the regulation of insurance first established as a state responsibility by three actions from 1835-1861. Next, the federal government’s standing to regulate insurance was debated through five federal Congressional bills and two federal Supreme court decisions with the final action being the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945 that established states’ responsibility for regulating insurance. Since state responsibility has been “established”, the federal Congress has voted on five bills that chip away at state responsibility for regulating insurance with the three most notable bills being the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) of 1985, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, a.k.a. ACA) of 2010. The major point with the insurance example and numerous others that exist is the persistent power tension between federal and state governments over who has the right and ability to set policy.

How to Influence the Policy Process

Advocacy, or seeking to influence public policy as a standalone activity, can sometimes seem a bit dishonest or disingenuous. However, advocacy is how all public policy comes into being. Policy makers view policy advocates as trusted partners in the policy making process who provide essential elements for the policymaking process such as constituent and industry feedback and concerns, as well as draft policy language or review of proposed policy language. This section will discuss the role of policy advocates and their importance in the policy making process.

The first rule of advocacy is to develop a trusting relationship with legislators, administrators, and their staff. While a relationship with a legislator or administrator may seem glamorous, veteran advocates know that the true source of influential power rests with the staff members. Most advocates will only get a few minutes with a legislator or administrator whereas they will often get several hours with a staff member to whom they will be able to lay out in great detail their policy concern, position, and plan. When working with a legislator, administrator, or staff member the primary characteristics necessary are honesty and integrity. The information shared by advocates could end up in legislation or rules affecting thousands to millions of citizens and residents and therefore must be of the highest level of accuracy and validity. More than one legislator has stated, “you will only lie to me once.” Advocates must clearly understand how important honesty and integrity of their information and the potential negative impact dishonest information can have on citizens, residents, and the reputation of the legislator or administrator. Other relational characteristics necessary for successful advocacy are the ability to frame solutions within the legislator or administrator’s political philosophy and developing the skill of being able to disagree without being disagreeable.

Next, advocates need to understand that most legislators and administrators consider themselves public servants who are trusted by their constituents to develop and implement public policy that is beneficial to their constituents. Public leaders are interested in their constituents and thus are open to attending organizational and association events, receiving newsletters, and other information that keeps them in touch with those they are serving. Advocates need to befriend and be willing to defend public leaders when they are attacked in public settings or the media. Finally, when working with public leaders or their staff, provide a clear ask or request. Do not be ambiguous, rather be very clear about what you are asking them to support and the benefits of doing so. Remember that public leaders view themselves as advocates for their constituents looking for solutions to public problems affecting their constituents.

Key Words

Advocacy: The act of speaking to or for something or someone in order to gain support.

Bicameral system: A two-body legislative body of government, frequently a house of representatives and a senate.

Excludable: A good that some are excluded from accessing, such as disability insurance.

Federalism: One of several forms of government, and the one we have in the US, where there are limited, and specific powers granted to the federal government and all other responsibilities fall with the states.

Incremental legislation: In the US it is most common for small changes to be made over time, gradually shifting practice, rather than legislation that completely replaces the former practice all at once.

Legislation: Laws in all their forms, in development through after passage and singly or as a group.

Negative liberty: Freedom from external constraints.

Nonexcludable: A good that anyone can access or use, such as a public park.

Nonrival: A good that many can access or use at the same time, such as a public road.

Policy entrepreneur: A person who works to develop and pass new, or revised, legislation.

Positive liberty: The ability to do what one wishes.

Purposive approach: The process of interpreting the purpose of legislation to develop rules for its implementation.

Rival: A good that only one can use, creating competition for the resource.

Textual approach: Following specific, and directive, language in legislation to develop rules for its implementation.

References

Congressional Research Service. (2022). U.S. Health Care CoverageandSpending.https://crsreports.congress.gov/ product/pdf/IF/IF10830

Higbea, R.J. & Cline, G.A. (2021) Government and Policy for U.S. Health Leaders. Jones & Bartlett Learning

Peterson KFF. (2022). Health System Tracker: Long-term trends inemployer-basedcoverage. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/long-term-trends- in-employer-based-coverage/

SocialSecurityAdministration.(1972).Bulletin. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v35n2/v35n2p3.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). Health insurance Coverage in the United States:2020. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/ Census/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-274.pdf