10

Healthcare Quality and Process Management

Tiffany C. Jackman, DHA

Auburn University at Montgomery

“Quality is not an act, it is a habit.” – Aristotle

Learning Objectives

- Explain the history of quality improvement.

- Define the six domains of healthcare quality.

- Describe developing a culture of quality using Kotter’s Change Model.

- Discuss continuous quality improvement leadership and teamwork

- Summarize the most widely used quality improvement methodologies in healthcare and examples of programs designed to evaluate quality.

Introduction

Quality improvement is a formal approach to the analysis of performance and the systematic efforts to improve it, according to CMS (2021). For each organization, the definition of quality depends largely on the stakeholders. In most service industries, customer satisfaction is often the primary measure. In healthcare, health outcomes also play a vital role in how we define quality. Quality improvement in healthcare is beyond a moral obligation to provide high-quality care, it is often incentivized with monetary rewards. This is often achieved through standardization of processes, reduction in variation of results, and improved patient outcomes (CMS, 2021).

The Evolution of Quality Improvement

The roots of quality can be traced to medieval Europe when 13th-century artisans would put their mark on produced goods. Similar to trademarks, master craftsmen’s marks served as proof of quality for consumers (ASQ, 2022a). In agriculture, farmers screen inferior products and meticulously select seed and breeding stock (Westcott, 2006). Some of the earliest seeds of quality management were sewn in the 1920s, during union opposition to workers’ conditions (Simon, 2022). A series of investigations conducted by Elton Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger in the 1920s called the Hawthorne Studies revealed that worker productivity could be affected by motivators other than money. Studies conducted by the duo additionally revealed a correlation between teamwork and success (Simon, 2022).

In the 1930s, Walter Shewhart developed methods for statistical analysis and quality control; however, it was not until the 1950s that quality improvement gained significant traction with organizations through the use of Total Quality Management (TQM), a term coined by W. Edwards Deming (Simon, 2022). In the late 1960s, Japanese businessperson, Kaoru Ishikawa, used the basic concepts of quality control to make great strides in Japan’s economic impact (Simon, 2022). Ishikawa created the cause-and-effect diagram (also called the fishbone diagram) to assist companies with brainstorming or problem-mapping potential root causes of undesirable outcomes (Simon, 2022). As a result of Japan’s strategies for total quality improvement, Dr. Joseph M. Juran predicted that Japanese goods would overtake the quality of US goods by the mid-1970s (Simon, 2022). Japanese manufacturers focused on improving organizational U.S. Healthcare System 6 processes. Subsequently, Japan did produce higher-quality exports at lower prices (Simon, 2022).

TQM did not gain traction in the US until the late 20th century. Dr. Joseph Jaran, often hailed as “the father of quality” management theory, was largely influenced by a visit to Japan (Jaran, 2022). Jaran wrote the Quality Control Handbook in 1951 and later created the Pareto Principle or “80/20 rule” which identified that a small percentage of a root cause can account for the largest effect in terms of defects or cost (Jaran, 2022). In other words, 80% of problem outcomes are caused by 20% of the process problems and inputs (Tardi, 2022). Jaran is also credited for the principles of quality as a management theory and his influence of providing workplace managers with education and training on quality processes is utilized today. The Juran Trilogy combines three elements of quality planning (design state), quality control (observation of ongoing processes), and quality improvement (refinement of processes to improve) (Jaran, 2022).

The quality improvement methodology exploded by the late 1990s with Motorola’s development of Six Sigma. Quality, in terms of patient safety, started trending following the publication of two Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports, To Err Is Human (IOM, 2000) and Crossing the Quality Chasm (IOM, 2001). The IOM identified six critical areas of the healthcare systems to ensure high-quality care. Healthcare provided should be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (IOM, 2001). These reports also highlighted the rising costs of healthcare in combination with the highly unacceptable rates of medical errors. While previous quality methodology focused on waste and costs of goods, these reports focused on the recognition of needless human suffering, loss of life, and lack of best practices for medical treatment (McLaughlin & Kaluzny, 2020). As a result, in 2008 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted a non-reimbursement policy for circumstances that were deemed “never events” mandated by section 5001(c) of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (Mattie & Webster, 2008). CMS further described “never events” as eight serious and preventable hospital-acquired conditions including pressure ulcers (stages III and IV); falls and trauma; catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI); catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI); administration of incompatible blood; air embolism; foreign object unintentionally retained after surgery, and surgical site infection (after bariatric surgery for obesity, certain orthopedic procedures, and bypass surgery) (Kuhn, 2008).

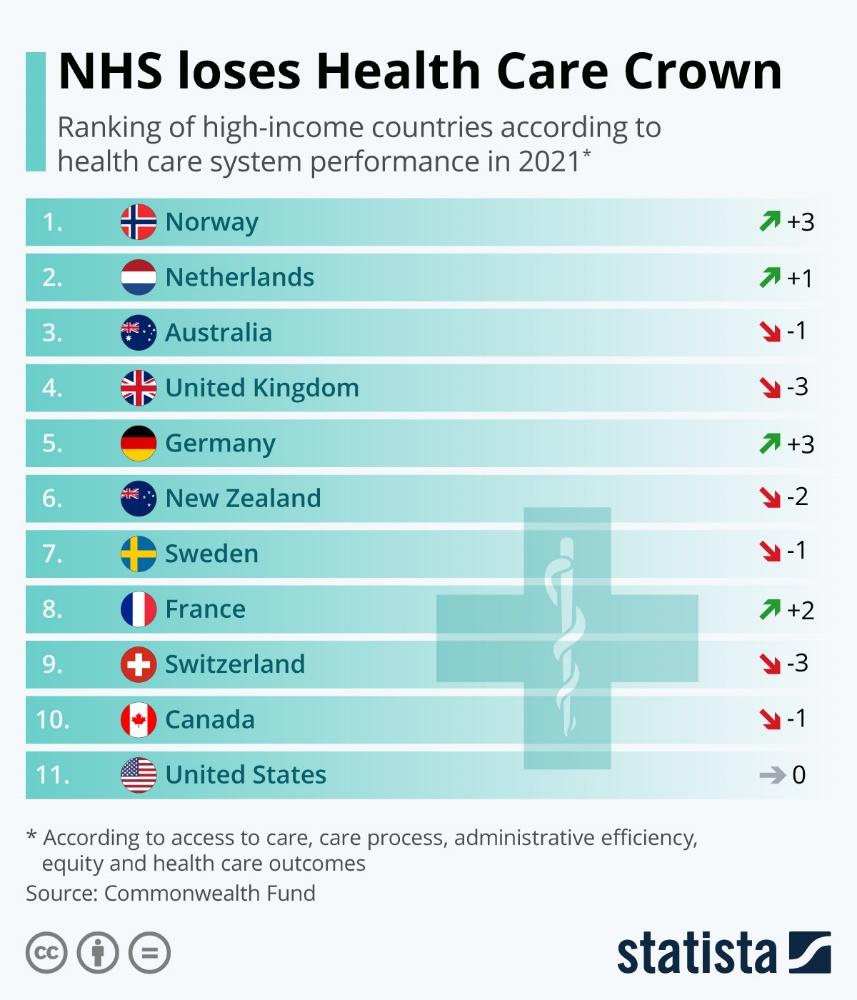

According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2018), national efforts to reduce “never events” prevented approximately 8,000 deaths and saved $2.9 billion in costs. However, despite Health and Human Services’ combined efforts with CMS to launch quality initiatives in healthcare starting in 2001, the last twenty years have not drastically improved the costs or quality outcomes as hoped. US healthcare continues to rank last in comparison to the top 11 wealthiest countries (Yang, 2022). The statistical review of overall rankings of healthcare system performance provides evidence that the US continues to lag in all areas, including access to care, care processes, administrative efficiency, equity, and healthcare outcomes (Schneider et al., 2021).

The complex US multi-payer system generates extra U.S. Healthcare System 8 bureaucratic tasks for providers and patients. Yang (2022) estimates $256 million in administrative waste per year performing these tasks. Furthermore, without universal health coverage, there continue to be large disparities in coverage for individuals with low-income.

Figure 1

Performance Outcomes of High-income Countries

The Definition of Quality

How do we define quality? This definition depends on the stakeholders. In manufacturing, this definition can be straightforward with stakeholders consisting of management, union officials, employees, and customers. In healthcare, the definition of quality can be much more complex and controversial because of the differing views of each stakeholder. Medical providers, employers, patients, and third-party payers are the stakeholders in health entities. Providers tend to view quality in a technical sense – accuracy of diagnosis, appropriateness of therapy, resulting in a good health outcome. Employers want to keep costs down but make workers efficient and provide quick delivery of care. Patients want clear communication, a compassionate experience, and a voice in their treatment decisions.

Patients expect that their employer will offer a wide variety of healthcare coverage options that can be customized to their specific needs and also want the employer to fund the majority of the cost of coverage. Employers want to maintain lower costs for their contributions. They also want employees to be compliant with their healthcare treatment and return to work quickly. Providers want to provide the best service using the most accurate tests and treatments. Insurance providers want providers to follow an evidence-based diagnostic plan to reach the most accurate diagnosis and treatment plan at the lowest cost. How do healthcare leaders coalesce these wants to provide a standard of care to meet quality standards?

The Six Domains of Health Care Quality

While the definition of quality could be generally stated as a standard of excellence measured by desired outcomes, there have been numerous trends in healthcare that focus on short-term or long-term outcomes. Quality comes when there is consistent conformance to performance standards. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality as “the extent to which healthcare services provided to individual patient populations improve desired health outcomes. To achieve this, healthcare must be safe, effective, timely, efficient, equitable, and people-center (WHO, 2017).” The World Health Organization suggests that a health system should seek to make improvements in six areas or dimensions of quality. Closely resembling the IOM’s characteristics mentioned previously in the chapter, these dimensions require that healthcare be:

- Safe: minimizing harm and risks associated with healthcare.

- Effective: providing treatments and interventions proven to work and avoiding those likely ineffective.

- Patient-centered: respecting individual preferences and values; involving patients in decisions.

- Timely: reducing unnecessary waits and delays in receiving care.

- Efficient: avoiding waste and using resources wisely.

- Equitable: ensuring everyone has access to high-quality care, regardless of background or circumstances (WHO, 2017).

The minimization of risks works in tandem with quality improvement. Risk management, by definition, is the process of assessing, managing, and mitigating losses. The basic methods for risk management are avoidance, retention, sharing, transferring, and loss prevention and reduction. In healthcare, risk management comprises the clinical and administrative systems, processes, and reports employed to detect, monitor, assess, mitigate, and prevent risks (NEJM Catalyst, 2018). “By employing risk management, healthcare organizations proactively and systematically safeguard patient safety as well as the organization’s assets, market share, accreditation, reimbursement levels, brand value, and community standing risks (NEJM Catalyst, 2018).” Risk management places focus on the importance of patient safety. Value-based payments use risk-bearing models for performance measures and bundled payments. To ensure the best care delivery possible, health professionals need tools to optimize the impact on the healthcare system and its patients while reducing risks. Understanding how to utilize quality improvement methodologies and tools is critical to meeting specific requirements set forth by Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for patient safety, risk management, core measures, and incident management.

From Triple Aim to Quintuple Aim

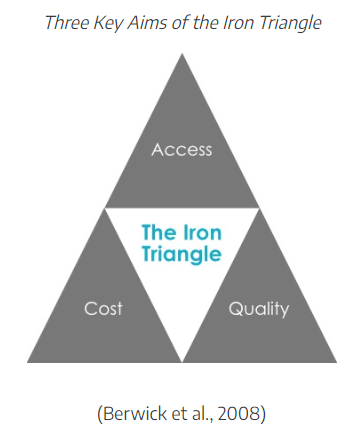

Triple Aim is an approach used to optimize health system performance by improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita costs of healthcare (IHI, 2016). U.S. healthcare is the costliest in the world, accounting for 19.7% of the gross domestic product (IHI, 2016). U.S. healthcare spending grew 4.1% to reach $4.5 trillion in 2022 (CMS, 2022c). Moreover, the population reached 92% insured, a historic high. Triple Aim strategies focus on improving the community beyond the hospitals and clinics that make up the healthcare system. To successfully integrate Triple Aim, at least five components are needed: partnership with individuals and families, the redesign of primary care, population health management, cost control platform, and systems integration and execution (IHI, 2016). Building on William Kissick’s Iron Triangle, the Triple Aim has three essential goals: improved access, enhanced quality, and controlled costs (Berwick et al., 2008).

Figure 2

The Iron Triangle

Later, the focus shifts from individual-centric care to population-focused well-being. This means prioritizing preventative measures and managing chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease, which disproportionately burden the healthcare system. From reactive treatment to proactive health maintenance. Instead of solely fighting acute illnesses, the focus moves to promoting overall health and wellness for entire populations.

This shift in thinking marks a significant step towards a more sustainable and holistic approach to healthcare, prioritizing not just individual healing but the well-being of entire communities.

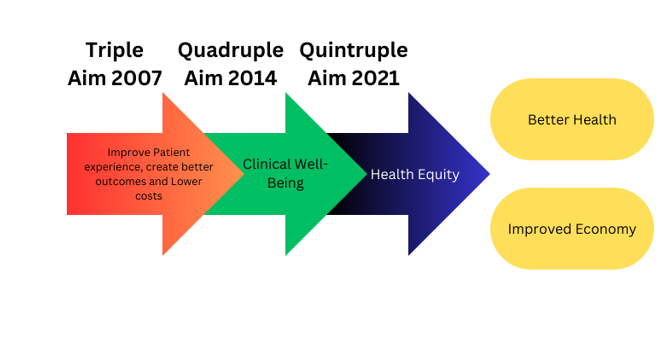

To further expand the focus on quality, the Triple Aim has evolved to include a more holistic view of quality. In 2014, the Aim model added an element focused on providers and addressing burnout and excessive cognitive load for healthcare providers (Lennon, 2023). Another extension to the model was added in 2021 to emphasize the importance of health equity. These aims were essential to align with the core principles of value-based care models to create a more equitable healthcare system (Lennon, 2023).

Figure 3

Aim Evolution

(Canva-generated Image)

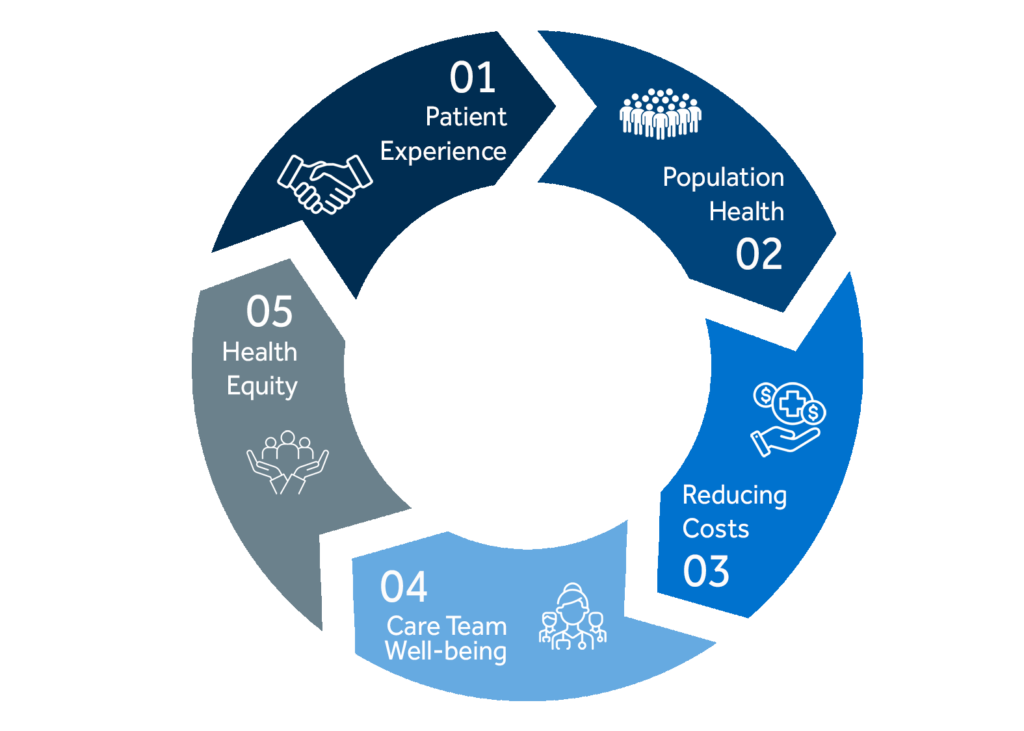

Health equity is not only an ethical imperative but also a critical factor in achieving better health outcomes and a more sustainable healthcare system (Lennon, 2023). The five aims of the Quintuple Aim model include:

Emphasis on patients: Value-based care prioritizes patient-centered care, tailoring treatments to individual needs for better outcomes and experiences. Quintuple Aim’s focus on enhancing patient experience, trust, and communication reinforces this.

Population health focus: Value-based care expands beyond individual patients, aiming to improve the health of whole populations. Quintuple Aim’s recognition of social determinants of health and preventive measures aligns with this.

Cost efficiency: Controlling healthcare costs while maintaining quality is key. Quintuple Aim’s “Reduce Costs” dimension encourages identifying inefficiencies and optimizing resource allocation.

Provider well-being: Quintuple Aim’s focus on “Improve Provider Well-being” acknowledges the importance of provider satisfaction and engagement for delivering high-quality care.

Care team collaboration: Health equity in value-based care involves fostering collaborative and inclusive care teams, addressing health disparities, and providing equitable care to improve patient and team satisfaction.

VIDEO LINK HCR Quintuple Aim Q4 2023 – YouTube

When patient outcomes improve, population health is managed effectively, costs are controlled, providers are engaged, and care teams collaborate efficiently, the healthcare system becomes more resilient and better equipped to meet the long-term needs of the population, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Quintuple Aim

(Lennon, 2023)

Population Health Management

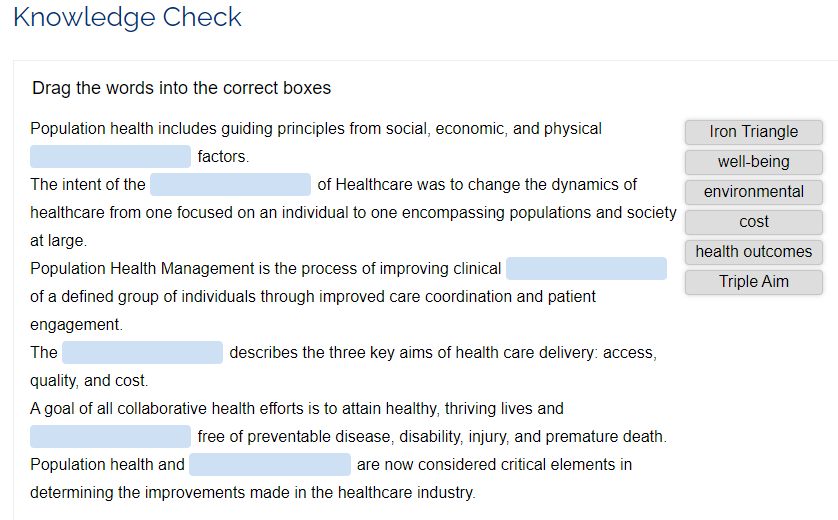

Population health encompasses the communities where individuals live, work, and unwind (Carlson, 2020). Population health, then, is about the overall health of a group, including how evenly or unevenly health outcomes are distributed among its members (Kindig & Stoddart, 2003).

Focusing on group health instead of individual cases has become crucial for healthcare delivery. This broader perspective acknowledges the diverse social, economic, and environmental factors that influence health (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012). To fully embrace this shift, the American Hospital Association (2023) proposes Population Health Management (PHM), merging healthcare with strong management practices. PHM moves beyond treating individual diseases to strategizing for group health, ultimately aiming for a triple win: better clinical outcomes, lower costs, and greater safety.

|

Definition: Population Health Management (PHM) “is the process of improving clinical health outcomes of a defined group of individuals through improved care coordination and patient engagement supported by appropriate financial and care models” (American Hospital Association, 2023). |

Since 1979, Healthy People has been charting a course for better national health. It all began with a groundbreaking report proposing a united healthcare strategy. Following editions built on this foundation, each decade sets new goals and tracks progress in tackling health disparities and improving well-being for all.

The latest chapter, Healthy People (HP) 2030, aims at a wide range of challenges, from chronic diseases to pandemics like COVID-19. With 355 evidence-based objectives and clear metrics, it serves as a blueprint for collaborative health efforts, including Population Health Management (PHM).

HP 2030 sets five overarching goals:

- Live thriving lives, free from preventable harm.

- Close the health gap and empower everyone with knowledge.

- Shape our surroundings to nurture health.

- Support healthy choices at every stage of life.

- Mobilize everyone to work towards a healthier future.

- These goals guide the way for healthcare professionals, policymakers, and individuals alike, paving the path for a healthier nation in the years to come.

|

Definition: Healthcare quality is “the degree to which healthcare services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, [AHRQ], 2020b). |

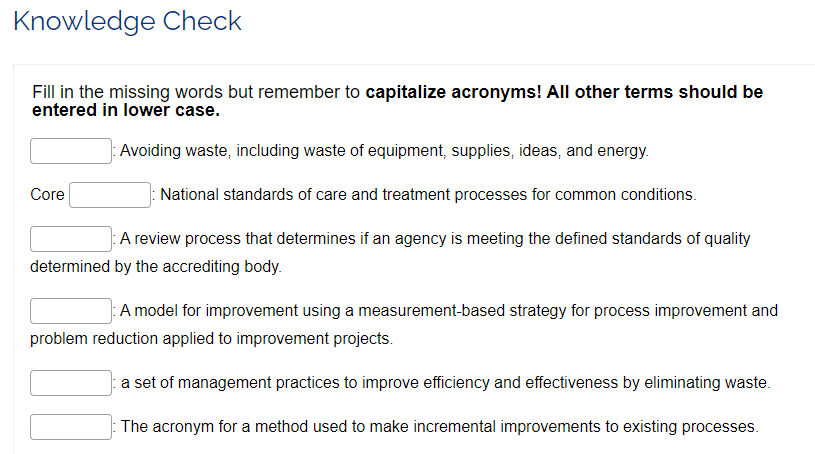

Quality Improvement Methods

Healthcare differs from other industries that rely on labor; increased productivity is more difficult to achieve. Effective performance improvement methodologies in healthcare have been slow to adapt. Healthcare providers are increasingly challenged to provide improved patient services at a faster pace. The traditional physician-centric model of healthcare must change. To improve efforts towards change, two models for performance improvement have been proven to improve quality and increase efficiency: Six Sigma and Lean. Additionally, Plan-Do-Study-Act or PDSA and Plan-Do-Check-Act or PDCA are two widely utilized improvement methodologies to improve processes.

I. Improvement Processes Models

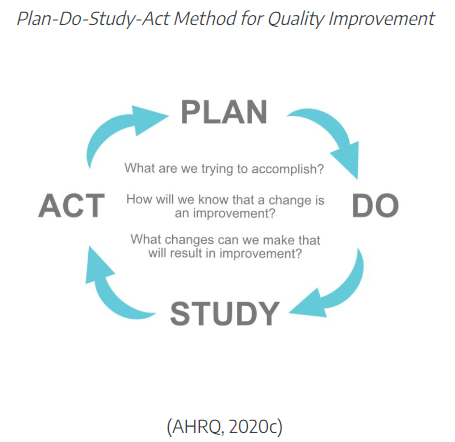

Plan-Do-Study-Act

One of the most commonly used methods of improvement is the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. Since quality improvement projects are typically team-based, PDSA places great emphasis on including the right people for success (Langley et al., 2009). Planning can be the most important part of a successful project. Change should be monitored and adjusted as needed. The cycle of PDSA allows for refinement of the change to be implemented on a broader scale after successful U.S. Healthcare System 20 changes have been identified (Langley et al., 2009). PDSA originated in 1986 as a more effective alternative to PDCA.

Plan-Do-Check-Act

Plan-Do-Check-Act is a model for carrying out change and an essential part of the “continuous improvement” processes. This four-stage method enables teams to avoid recurring mistakes in the improvement process by analyzing the current process and clarifying a plan. This model includes testing, analyzing results, and improving processes. This methodology places heavy emphasis on the “check” phase to ensure the initial plan is working. The model requires a mandatory commitment to continuous improvement to have a positive impact on productivity and efficiency.

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle reigns supreme as one of the most popular tools for quality improvement in healthcare. Introduced in 1986 as an upgrade to its predecessor, PDSA emphasizes teamwork and small, iterative steps for driving better outcomes.

Here’s why PDSA works:

- Team-centric: It puts the right people together, maximizing the potential for success.

- Planning power: Strong planning lays the foundation for effective action.

- Agile and adaptable: Monitoring and adjusting on the fly ensures constant improvement.

- Success breeds expansion: Proven changes scale up effortlessly after thorough testing.

Looking for a deeper dive? Check out these resources:

- The PDSA Step-by-Step (Administration for Children & Families, 2018)

- Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Directions and Examples (AHRQ, 2020a)

PDSA gives healthcare teams a flexible framework for continuous improvement, empowering them to deliver better care with each cycle.

Figure 5

PDSA Cycle

(AHRQ, 2020c)

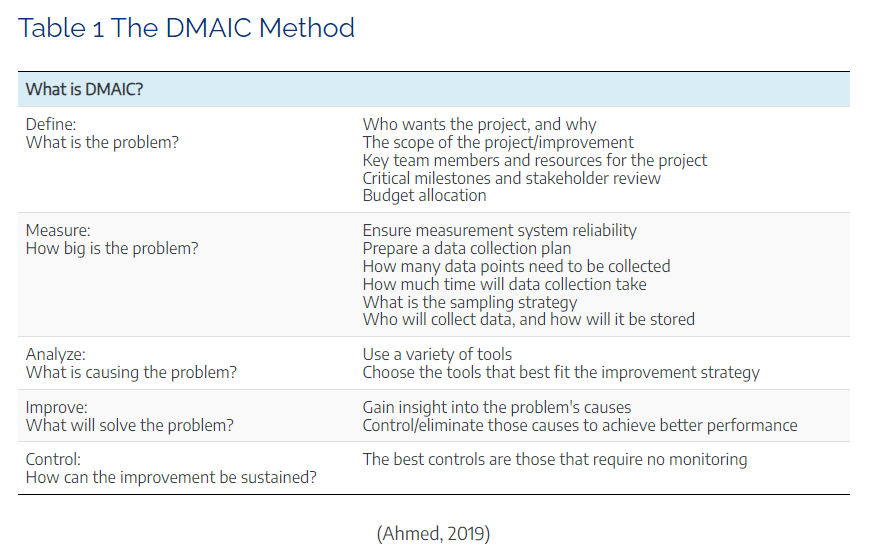

II. Six Sigma

Six Sigma is another model for improvement using a measurement-based strategy for process improvement and problem reduction applied to improvement projects. The term Six Sigma derives from the Greek letter σ (sigma), used to denote the standard deviation from the mean or how far something deviates from perfection. By definition, 6 Sigma is the equivalent of 3.4 defects or errors per million (Seecof, 2013). Six Sigma tackles improvement through cold, hard data. This measurement-based approach zeros in on process flaws and shrinks them down to near-nonexistence.

Six Sigma models include DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, control) and DMADV (define, measure, analyze, design, verify). DMAIC (Table 1.) is used for existing processes to make incremental improvements, whereas DMADV is used to develop new processes at Six Sigma quality levels (Seecof, 2013). For this lesson, let’s focus on DMAIC, which is a formalized problem-solving method designed to improve the effectiveness and ultimate efficiency of the organization.

DMAIC: Used for existing processes, this five-step cycle dissects the problem, gathers data, analyzes it, implements improvements, and then puts controls in place to keep things on track. It’s like a meticulous detective solving a mystery.

DMADV: When a new process needs to be built from scratch, DMADV steps in. It follows a similar path to DMAIC but adds “design” and “verify” steps to ensure the new process starts at peak performance. Think of it as building a flawless machine, bolt by meticulously placed bolt.

Table 1

DMAIC Method

(Ahmed, 2019)

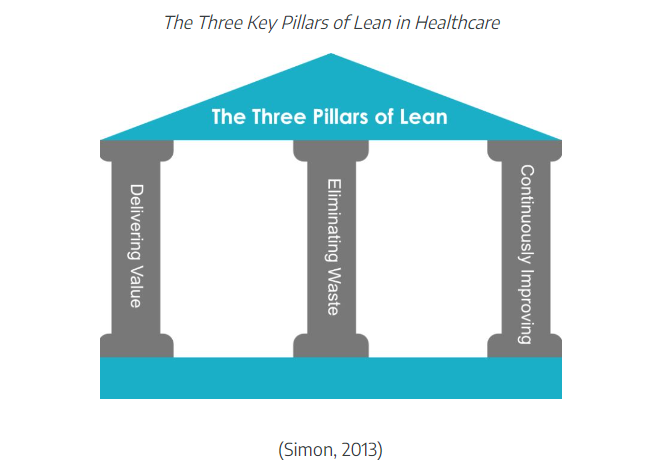

Lean methodology designates eight areas of waste: defects, overproduction, waiting, transportation, inventory, motion, extra-processing, and non-utilized or underutilized talent (ASQ, 2022a). The goal is to provide the perfect value to the customer [patient] with zero waste (Management and Strategy Institute, n.d.). Some examples in healthcare that may seem insignificant include the following:

III. Lean

|

Definition: Lean is “a set of management practices to improve efficiency and effectiveness by eliminating waste” (The American Society for Quality, 2023a). |

Lean methodology designates eight areas of waste: defects, overproduction, waiting, transportation, inventory, motion, extra-processing, and non-utilized or underutilized talent (ASQ, 2022a). The goal is to provide the perfect value to the customer [patient] with zero waste (Management and Strategy Institute, n.d.). Some examples in healthcare that may seem insignificant include the following:

- Reducing inventory, especially medical supplies that have expiration dates.

- Reducing or maximizing the use of space.

- Quicker response times and/or reduced wait times.

- Reductions of defects, medical errors, and mistakes.

- Increasing the overall productivity and utilization of employees.

Using Lean concepts can improve the quality of patient care whilst saving time and resources and reducing the length of stay, essentially providing fewer mistakes, accidents, and errors resulting in better health outcomes. Think of Lean as a value-adding machine for healthcare with a mission to reduce waste and anything that doesn’t directly benefit the patient. This includes errors, poor organization, and communication gaps that slow things down and create frustration. Simon (2013) provides the three pillars of Lean:

- Patient-first value: Every step of the process must have meaning for the patient, not just the provider.

- Waste elimination: Every non-essential activity gets the boot, freeing up resources for better care.

- Continuous improvement: It’s never “done” in Lean. Teams constantly seek ways to refine processes and deliver even better patient experiences.

Figure 6

Pillars of Lean

(Simon, 2013)

Think of it like dissecting a recipe to find the secret ingredient for efficiency. Every step is scrutinized, optimized, and streamlined to make the process smoother, faster, and ultimately, better for the patient.

“Value stream mapping is a workplace efficiency tool designed to combine material processing steps with information flow, along with other important related data. VSM is an essential Lean tool for an organization wanting to plan, implement, and improve while on its Lean journey. VSM helps users create a solid implementation plan to maximize their available resources and help ensure that materials and time are used efficiently.”

|

Definition: Value stream mapping is “a lean tool that employs a flowchart documenting every step in the process. Many Lean practitioners see VSM as a fundamental tool to identify waste, reduce process cycle times, and implement process improvement” (American Society for Quality, 2023b). |

Using Lean concepts can improve the quality of patient care. To illustrate, review these Lean implementation case studies (Purdue University, 2022):

- Rural hospital uses Lean Daily Improvement to increase patient feedback

- Primary care practice improves EHR efficiency for better physician-patient interaction

IV. Lean Six Sigma

Think of Lean and Six Sigma as two superheroes, each bringing unique powers to improve healthcare. Lean, the waste-busting warrior, cuts down on unnecessary activities and delays. Six Sigma, the precision engineer, minimizes defects and errors. Together, they form Lean Six Sigma, a powerhouse of improvement that’s been transforming healthcare since the 2000s.

Why is this combo so unbeatable?

Lean adds value: by eliminating waste, it ensures every step focuses on patient needs.

Six Sigma tackles flaws: it uses data and problem-solving to reduce defects and errors.

Lean speeds things up: it streamlines processes, making Six Sigma even more efficient.

But unleashing these superheroes requires careful preparation.

Here’s the recipe for success:

- Set clear goals: Know what you want to achieve.

- Communicate and share: Foster a collaborative environment where everyone feels heard.

- Start small: Take it one step at a time to build momentum.

- Find a change agent: Identify someone who can champion the process, even if they were initially hesitant.

- Gain buy-in: Respect concerns and explain how success benefits everyone.

Remember, even the strongest superheroes need allies. The example of the skeptical physician turned champion shows how winning over key individuals can be the tipping point for success. In short, Lean Six Sigma is a powerful tool for healthcare improvement, but its effectiveness hinges on clear goals, open communication, and a strategic approach to engaging the team, especially initially hesitant members.

Lean is all about streamlining healthcare to put the patient’s needs front and center, every step of the way. Lean Six Sigma is a philosophy of improvement that values defect prevention over defect detection (ASQ, 2022b). It drives patient satisfaction and bottom-line results by reducing variation, waste, and cycle time, while simultaneously promoting process standardization and flow. The combination, Lean Six Sigma, became mainstream in healthcare by the 2000s. Lean creates value by minimizing waste, while Six Sigma reduces defects through effective problem-solving. Lean can accelerate the Six Sigma process, making it more efficient. To prepare your team for change using Lean and Six Sigma, be sure to

- Set clear goals and communicate.

- Establish a Lean mindset by cultivating shared leadership among the team.

- Start small and find a change agent.

Often, the best change agent can be the provider or employee that will be your strongest opposition. Gaining their trust, respect, and ultimately their buy-in can be your biggest asset. For example, several senior physicians in a practice opposed the rollout of a new electronic health record (EHR) system. Getting the strongest opposition on board by explaining that the success of this rollout would weigh heavily on the administrator’s job performance was critical. His desire to ensure his administrator’s success in the eyes of leadership was enough to get him on board. He became the physician champion by gaining the buy-in from the rest of the providers. This step was the lynchpin to the project’s success. Some examples of ways to use Lean include the following scenarios:

- Providers walk down the hall to a printer. This effort is wasted motion and time. A more efficient solution may be to install a printer at both ends of the clinic.

- The new electronic health record (EHR) system is not optimized, and physicians must scroll through hundreds of diagnosis and billing codes. Consider condensing the list of available codes to the top five or ten. This small change could save them a significant amount of time and frustration.

- A nurse performing clerical duties may need to redistribute some tasks to non-licensed employees, thus optimizing their nursing skills on more appropriate tasks.

- One floor is short-staffed, while another floor has a low patient volume. Nursing staff may need to be redistributed to help balance the workload on the other floors.

Measures of Quality

Quality measures are tools that help quantify healthcare processes, outcomes, patient perceptions, and organizational systems that are combined to provide care related to meeting quality goals. As mentioned, tools can help measure the six domains of quality: patient-centered outcomes such as safety, efficiency, equitability, effectiveness, timeliness, and patient-centeredness. Examples of quality measures in healthcare include the:

- Magnet Recognition Program

- Value-based reimbursement models

- CMS quality initiatives

- Accreditation review process

- Core measures

- Patient safety goals

I. Magnet Recognition Program

Imagine a stamp of excellence for healthcare, awarded to organizations where nurses truly thrive. That’s the Magnet Recognition Program, a prestigious accreditation bestowed by the American Nurses Credentialing Center. Magnet hospitals prioritize nursing excellence, aligning their goals with improved patient outcomes. This translates to continuous education and development for nurses, empowering them to provide top-notch care. For patients, the Magnet seal is a beacon of hope. It signifies an environment where nurses are empowered, supported, and equipped to deliver the highest quality care. It’s like a promise whispered on the breeze: “You’re in good hands here.” The Magnet Recognition Program celebrates the vital role of nurses and underscores their essential contribution to quality healthcare.

II. Reimbursement Models

What’s quality care? It’s not just about good bedside manners anymore. Reimbursement models used by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers are increasingly tying financial rewards to positive patient outcomes. This means preventing things like avoidable infections and ensuring evidence-based practices are followed. Hospitals don’t get paid for avoidable complications, so they invest in nurses who provide top-notch care. Nurses, in turn, need to document their actions meticulously to prove they meet quality performance criteria. It’s a win-win: patients get better care, and hospitals stay financially healthy.

Value-based reimbursement is changing the game. It’s pushing healthcare towards data-driven, evidence-based practices, with nurses playing a crucial role in both delivering and documenting quality care. There are five original value-based programs; their goal is to link provider performance of quality measures to provider payment (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2022a):

End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program – The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) administers the End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program to promote high-quality services in renal dialysis facilities. The first of its kind in Medicare, this program changes the way CMS pays for the treatment of patients who receive dialysis by linking a portion of payment directly to facilities’ performance on quality-of-care measures.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program – The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (VBP) rewards acute care hospitals with incentive payments for the quality of care provided in the inpatient hospital setting. The Hospital VBP Program encourages hospitals to improve the quality, efficiency, patient experience, and safety of care that Medicare beneficiaries receive during acute care inpatient stays.

Hospital Readmission Reduction Program – The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program is a Medicare value-based purchasing program that encourages hospitals to improve communication and care coordination to better engage patients and caregivers in discharge plans and, in turn, reduce avoidable readmissions.

Value Modifier Program (also called the Physician Value-Based Modifier) – The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) under the Quality Payment Program replaced the Physician Feedback/Value-Based Payment Modifier Program on January 1, 2019. The Physician Feedback Program provided comparative performance information to solo practitioners and medical practice groups, as part of Medicare’s efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of medical care furnished to Medicare beneficiaries.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions Reduction Program – The Hospital-Acquired Conditions Reduction Program encourages hospitals to improve patients’ safety and reduce the number of conditions people experience during their time in a hospital, such as pressure sores and hip fractures after surgery. This program encourages hospitals to improve patients’ safety and implement best practices to reduce the rates of infections associated with healthcare.

Other value-based programs include (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2022a):

Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing – The CMS awards incentive payments to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) through the Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing (SNF VBP) Program to encourage SNFs to improve the quality of care they provide to Medicare beneficiaries. For the Fiscal Year 2024 Program year, performance in the SNF VBP Program is based on a single measure of all-cause hospital readmissions.

Home Health Value-Based Purchasing – The CMS Innovation Center implemented the Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP) Model (i.e., the original Model) in nine (9) states on January 1, 2016. The specific goals of the original Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (HHVBP) Model were to provide incentives for better quality care with greater efficiency, study new potential quality and efficiency measures for appropriateness in the home health setting, and enhance the current public reporting process. The expanded HHVBP Model began on January 1, 2022, and includes Medicare-certified Home Health Agencies in all fifty (50) states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories. Under the expanded HHVBP Model, HHAs receive adjustments to their Medicare fee-for-service payments based on their performance against a set of quality measures relative to their peers’ performance.

III. CMS Quality Initiatives

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) establishes quality initiatives focusing on several key quality measures of healthcare. These quality measures provide a comprehensive understanding and evaluation of the care an organization delivers and responses from the patients who receive care. These quality measures evaluate many areas of healthcare, including the following (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2022b):

- Health outcomes

- Clinical processes

- Patient safety

- Efficient use of healthcare resources

- Care coordination

- Patient engagement in their own care

- Patient perceptions of their care

These measures of quality focus on providing the care the patient needs when the patient needs it in an affordable, safe, and effective manner. It also means engaging and involving the patient, so they take ownership of their care at home.

IV. Accreditation

To demonstrate a healthcare organization’s commitment to quality, obtaining accreditation allows facilities to demonstrate their ability to meet official regulatory requirements and standards. Deeming Authority is granted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS). When CMS provides “deemed status” for an organization, it demonstrates that the organization exceeds the expectations for a particular area of expertise. Deemed accrediting bodies can provide accreditation to entities that achieve and maintain compliance with quality standards (CMS, 2021).

The Joint Commission (2022) has been the leading accrediting body for setting and monitoring quality standards in healthcare since 1951. It is the nation’s oldest and largest standards-setting and accrediting body in healthcare. Joint Commission (2022) is an independent, not-for-profit that seeks to improve healthcare continuously with collaboration from stakeholders through the evaluation of effective and safe patient care. With CMS deeming authority, Joint Commission (2022) can officially conduct on-site surveys of organizations to determine their compliance with set safety and quality standards. In the United States, there are more than 22,000 accredited organizations and programs. Joint Commission (2022) recommends healthcare entities focus on strategies to revitalize and retain the healthcare workforce; cultivate and strengthen safety culture; and provide tools to reduce mortality and increase compliance in pursuit of zero harm.

Although it is the most recognized accreditor, Joint Commission is not the only accrediting body. Some of the major organizations approved for accreditation by CMS include

- National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)

- The Joint Commission (TJC)

- Utilization Review Accreditation Commission (URAC)

- Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF)

- Council on Accreditation (COA)

Others:

- Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program (HFAP)

- Center for Improvement in Healthcare Quality (CIHQ)Community Healthcare Accreditation Program (CHAP)

- DNV GL Healthcare (DNV)

- Institute for Medical Quality (IMV)

- Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC)

- American Medical Accreditation Program (AMAP)

- American Accreditation Healthcare Commission (ACHC)

Organizations must meet rigorous standards of confidentiality, access, customer service, and quality improvement to earn a seal of approval from accrediting bodies.

V. Core Measures

Core measures are the blueprints for better patient care. Core measures are national standards for treating common conditions that aim to reduce complications and improve patient outcomes. These national standards of care outline proven processes for treating common conditions, helping to reduce complications and improve outcomes. Hospitals track their compliance with these measures, reporting their success rates to organizations like Joint Commission and CMS.

It’s a shared language for quality healthcare. In 2003, a big step was taken: The Joint Commission and CMS united on a single set of core measures, creating a unified roadmap for improvement known as the Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures. These measures cover a wide range, from vaccination guidelines to stroke treatment, ensuring high-quality care across diverse areas.

For healthcare providers, knowing and following these core measures is essential. It’s not just about checking boxes; it’s about putting patient well-being at the center of every decision. By adhering to these proven practices, providers can contribute to a national effort to deliver consistently better care.

VI. Patient Safety Goals

Patient safety goals are guidelines specifically for organizations accredited by Joint Commission that focus on healthcare safety problems and ways to solve them. Imagine a roadmap to safer healthcare, filled with clear directions and solutions for common obstacles. That’s what Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) offer. Established in 2003 and constantly updated, these guidelines serve as a compass for accredited organizations to steer away from potential dangers and deliver high-quality, safe care.

Culture of Quality

Culture is considered the essence of organizational function. It represents the values, norms, and assumptions shared by the members of the organization that are shaped by communicating standards of behavior to policies and procedures (Westcott, 2006). Most cultural influences begin with orientation or organizational training and solidify with peer-to-peer interactions. On a deeper level, organizational culture can manifest in ways that employees may not be continuously aware of. Furthermore, changing an organization’s culture can be extremely difficult and require time. Establishing a culture of quality is essential for any healthcare entity. A healthy organizational culture and employee morale result in more positive patient outcomes.

Joint Commission urges health organizations to embrace a culture that is non-punitive for reporting. In quality improvement, the term is coined as blameless culture. The aim of a blameless culture is not to be confused with “blame-free,” but rather a culture that balances learning with accountability, uniformly assesses errors and patterns, and eliminates unprofessional behaviors. A culture of safety focuses on attributes such as trust, reporting, and improvement. For safety culture to progress, elements of that culture must be measured, evaluated, analyzed, and result in specific interventions. A safety and quality culture consists of:

- High levels of trust

- Codes of behavior that are self-governed

- Personal accountability-recognized by all staff

- Equitable and transparent disciplinary procedures

- Close calls and unsafe conditions are routinely reported

- Proactive assessment of system weaknesses and addressing those weaknesses

John Kotter (1996) developed an eight-stage process for creating major change within the organizational culture and teamwork called Kotter’s Change Model, which includes the following steps:

- Establishing a sense of urgency

- Creating a guiding coalition

- Developing a vision and strategy

- Communicating the change vision for buy-in

- Empowering broad-based action (removing obstacles)

- Generating short-term wins

- Consolidating gains and producing more change

- Anchoring new approaches in the culture (make the change stick)

Kotter suggests preventing the status quo by instilling a sense of urgency. This does not imply that decisions should be rushed, but rather that people need to make the extra effort to make needed sacrifices (McLaughlin & Kaluzny, 2020). While each step of Kotter’s model guides the entire change process, stepping a single step could result in serious problems. This model is a top-down approach and can build frustration for dissatisfied employees. Therefore, heavy emphasis should be placed on the involvement of employees for overall success. Major emphasis should be placed on preparing employees for building acceptability to change instead of the actual change process.

Continuous Quality Improvement for Leadership and Teamwork

Quality improvement is a team-based process that allows groups to focus on a common goal. The dynamics of that team will differ from project to project. However, standardized processes should be in place to ensure team function, accountability, and success. Some teams have roles and leaders, while others may not. What is needed to create a successful team? Since much of the success of a project is based on the importance of a successful team, let’s look more deeply into examples of effective teams.

Clinical Leader

A person with authority in the organization must be available to implement the changes suggested. This person’s expertise is required to gain an understanding of the clinical implications of the proposed changes. One small change in an area can have a ripple effect on other areas of the health system (Langley et al., 2009).

Technical Expert

A person who best understands the processes of care can provide technical support by helping the team decide which measures would best determine success. This person’s expertise can aid in determining appropriate collection methods to obtain the specific data. Additionally, they may be able to choose the best measurement tools for the project (Langley et al., 2009).

Day-to-Day Leadership

The day-to-day leader drives the project by overseeing the data collection and performing tests. Their expertise is needed to understand the details of the system and how changes will affect other areas of the system. This person will work effectively with the physician champion(s) (Langley et al., 2009).

Project Sponsor

A sponsor is someone with the executive authority to either provide or act as the liaison with other areas of the system. They can provide resources and help navigate barriers on behalf of the team. This person may also hold team members accountable for their role and monitor the team’s progress (Langley et al., 2009).

Conclusion

The Population Health Management (PHM) has transitioned healthcare from a disease-only treatment model for an individual to a model that requires clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and safer health outcomes. Healthy People (HP) 2030, lists 355 core objectives ranging from mitigating contagious diseases to reducing chronic diseases. The Triple Aim model has been expanded to include professional well-being and health equity in addition to the existing pillars of increasing access to care, improving quality of care, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare. The Quintuple Aim: A key PHM component, this philosophy aims to:

- Improve patient experience: Make healthcare more welcoming and efficient.

- Optimize population health: Promote healthy communities and prevent illness.

- Reduce healthcare costs: Lower per capita spending without compromising quality.

- Add value for professionals: Ensuring the professionals can sustainably provide care.

- Social justice and inclusion: Achieve the same care for everyone, especially those who are vulnerable.

Healthcare quality is characterized as care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Four widely utilized improvement methodologies used to improve processes and healthcare quality include Plan-Do-Study-Act, Six Sigma, Lean, and Lean Six Sigma.

- Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA): This iterative cycle encourages small, rapid tests of change, allowing for quick learning and adjustments.

- Six Sigma: Focused on reducing defects and eliminating waste, Six Sigma uses data-driven tools to streamline processes and optimize quality.

- Lean: Inspired by manufacturing principles, Lean prioritizes eliminating non-value adding activities, promoting efficient flow and patient-centered care.

- Lean Six Sigma: Blending the best of both worlds, this hybrid approach combines Lean’s process focus with Six Sigma’s data-driven precision.

These methodologies offer flexible tools to navigate the unique complexities of healthcare and drive meaningful improvement in both processes and patient experience.

Various measures assess and promote healthcare quality, including:

- Magnet Recognition Program: Awards excellence in nursing care.

- Value-based reimbursement: Rewards good outcomes with financial incentives.

- CMS quality initiatives: Set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

- Accreditation review process: Ensures hospitals meet quality standards.

- Core measures: National standards for specific conditions.

- Patient safety goals: Guidelines to prevent healthcare errors.

The U.S. pays far more per capita than other high-income countries, yet health outcomes are not consistently better. The aging population, expensive technology, high drug prices, the Affordable Care Act, and social determinants of health all contribute to these elevated costs.

Attribution

“Introduction to the U.S. Healthcare System” by Thomas A. Clobes is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0  . Chapter 11

. Chapter 11

”EXPLORING THE U.S. HEALTHCARE SYSTEM” by Karen Valaitis is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0  . Chapter 4

. Chapter 4

Key Words

Buy-in – Agreement to support a decision.

Six Sigma – a philosophy that uses improvement tools, methods, and statistical analysis to drive defects to zero.

Lean – a philosophy based on the use of tools that focus on production systems, scheduling, and wait times to eliminate waste.

Total Quality Management (TQM) – a philosophy or approach to management characterized by principles, practices, and techniques aimed at customer focus, continuous improvement, and teamwork.

Quintuple Aim – a framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) to optimize health system performance

References

Administration for Children & Families. (2018). Module 5: The PDSA Cycle step by step. Continuous Quality Improvement Toolkit. A Resource for Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program Awardees. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/continuous-quality-improvement-toolkit-resource-maternal-infant-and-early-childhood-4

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2018). Declines in hospital-acquired conditions save 8,000 lives and $2.9 billion in costs. US Department of Health & Human Services AHRQ Archive [Press Releases]. https://archive.ahrq.gov/news/newsroom/press-releases/2018/declines-in-hacs.html

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2020a). Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) directions and examples. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, 2nd

Edition. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2020b). Understanding quality measurement. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html

Ahmed, S. (2019). Integrating DMAIC approach of Lean Six Sigma and theory of constraints toward quality improvement in healthcare. Reviews on Environmental Health, 34(4), 427-434. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2019-0003

American Hospital Association. (2023). What is population health management? https://www.aha.org/center/population-health-management

American Nurses Association. (n.d.). ANCC Magnet Recognition Program. https://www.nursingworld.org/organizational-programs/magnet/#:~:text=The%20Magnet%20Recognition%20Program%20designates,the%20whole%20of%20an%20organization.

American Society for Quality. (2023a). What is Six Sigma? https://asq.org/quality-resources/six-sigma

American Society for Quality. (2023b). What is value-stream mapping (VSM)? https://asq.org/quality-resources/lean/value-stream-mapping#:~:text=Value%20stream%20mapping%20(VSM)%20is,times%2C%20and%20implement%20process%20improvement.

Berwick, D. M., Nolan, T. W., & Whittington, J. (2008). The Triple Aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs, 27(3), 759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

Carlson, L. M. (2020). Health is where we live, work and play — and in our ZIP codes: Tackling social determinants of health. American Public Health Association. The Nation’s Health, 50 (1), 3. https://www.thenationshealth.org/content/50/1/3.1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Healthy People 2030. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthypeople/hp2030/hp2030.htm

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (2021). Quality measurement and quality improvement. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-PatientAssessment-Instruments/MMS/Quality-Measure-and-QualityImprovement-#:~:text=Quality%20improvement%20is%20the%20framework,%2C%20healthcare%20systems%2C%20and%20organizations.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2022a). What are the value-based programs? https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2022b). Quality measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022c). NHE fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet

Healthy People 2030. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health/

Institute of Medicine. (1996). Primary care: America’s health in a new era (M. S. Donaldson, K. D. Yordy, K. N. Lohr, & N. A. Vanselow, Eds.). Committee on the Future of Primary Care. National Academies Press. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25121221/

Institute of Medicine. (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (B. D. Smedley, A. Y. Stith, & A. R. Nelson, Eds.). Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220358/

Institute of Medicine. (2009). America’s uninsured crisis: Consequences for health and health care. Committee on Health Insurance Status and Its Consequences. National Academies Press. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25009923/

Institute of Medicine. (2013). Organizational change to improve health literacy: Workshop summary. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201914/

Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9728

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st Century. National Academy Press. doi: 10.17226/10027

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M., & Donaldson, M. S. (Eds.). (2000). National Academy Press. doi: 10.17226/9728

James, J. (2012). Pay-for-performance. Health Affairs, 34(8), 1-6. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20121011.90233/full/

Jaran. (2022). The History of Quality. https://www.juran.com/ blog/the-history-of-quality/

John Hopkins Medicine. (2023). Core measures. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/patient_safety/core_measures.html

Kindig, D., & Stoddart, G. (2003). What is population health? American Journal of Public Health, 93(3), 380-383. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.3.380

Kuhn, H. B. (2008). Patient safety: CMS Initiatives addressing never events. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). https://downloads.cms.gov/cmsgov/archived-downloads/smdl/downloads/smd073108.pdf

Langley, G. J., Moen, R. D., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (2009). The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Lennon, Y. (2023). The Quintuple Aim: What Is It and Why Does it Matter? CHESS Health Solutions https://www.chesshealthsolutions.com/2023/08/01/the-quintuple-aim-what-is-it-and-why-does-it-matter/

Mattie, A. S., & Webster, B. L. (2008). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ “never events”: An analysis and recommendations to hospitals. The Health Care Manager, 27(4), 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCM.0b013e31818c8037

National Center for Health Statistics. (2022). Life expectancy in the U.S. dropped for the second year in a row in 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2022/20220831.htm

New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst (NEJM Catalyst). (2018, Apr 25). What is risk management in healthcare? New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst: Innovations in Care Delivery. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0197

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Healthy People 2030 framework. https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2021). History of healthy people https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/healthy-people/about-healthy-people

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2012). What is the population health approach? https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/population-health-approach.html

Purdue University. (2022). Lean healthcare case studies. https://health.tap.purdue.edu/services/process-improvement-for-healthcare/lean-healthcare-case-studies/

Schneider, E. C., Shah, A., Doty, M. M., Tikkanen, R., Fields, K., Williams, R. D. (2021). Reflecting poorly: Health care in the U.S. compared to other high-income countries. Mirror, Mirror 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/aug/mirror-mirror-2021-reflecting-poorly

Seecof, D. (2013). Applying Six Sigma to patient care. ISIXSIGMA. https://www.isixsigma.com/industries/healthcare/applying-six-sigma-patient-care/

Simon, K. (2013). What is Lean management? ISIXSIGMA. https://www.isixsigma.com/methodology/lean-methodology/what-is-lean-manufacturing/

Stevens, K. R. (2013). The impact of evidence-based practice in nursing and the next big ideas. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.3912/ojin.vol18no02man04

Tardi, C. (2022). What is the 80-20 rule? Investopedia. 80-20 Rule Definition & Example (Pareto Principle) (investopedia.com) https://www.investopedia.com/terms/1/80-20-rule.asp

Yang, J. (2022). Health care process ranking of 11 select countries’ health care systems 2021. Statista. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1290422/health-caresystem-care-process-ranking-of-select-countries

Young, K. J. (2023, Nov. 17). HCR Quintuple Aim Q4 2023 [Video]. YouTube. HCR Quintuple Aim Q4 2023 HCR Quintuple Aim Q4 2023 – YouTube