8

Managed Care & Reimbursement

Anastasia Miller, PhD

University of Louisville

Patricia Driscoll, JD

Texas Woman’s University

“Managed care is an important element in the American health care system because it emphasizes preventive care and coordinated treatment, which are essential for maintaining public health and managing healthcare expenses.” – Tom Daschle

Learning Objectives

- Define and examine the development of managed care delivery models

- Identify the financial reimbursement methods commonly associated with various managed care models.

- Discuss Value Based Purchasing and illustrate how ACOs exemplify it.

- Examine newest managed care models: ACOs and PCMHs.

- Discuss Medicare Advantage and how they are providing managed care for the elderly.

Introduction

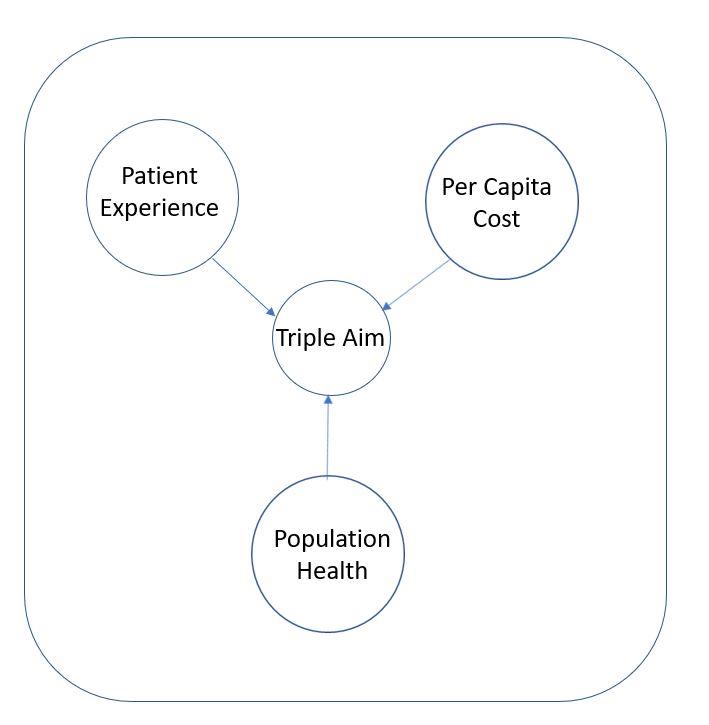

The main idea behind managed care is simple: coordinating care to reduce cost and improve outcomes (Namburi & Tadi, 2022). Although this idea predates the phrase “Triple Aim”, it can be best expressed by this term created by the researchers at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) (Berwick, Nolan & Whittington, 2008): simultaneously improving patient experience of care, improving population heath, and reducing the per capita costs of care. It has since officially become part of the national healthcare strategy and have been incorporated into The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) (Whittington, et al, 2015). There are many types of managed care – this chapter will cover some of the more common arrangements of managed care and the associated methods of reimbursement.

What is Managed Care?

Managed care organizations or MCOs are organizations that are somehow integrated and coordinated to provide care to a specific patient population. The main overreaching goals are to keep costs down while providing high quality care for patients (Heaton & Tadi, 2022). While there are few universal truths when it comes to MCOs, as you can always find a random example of an organization that does not fit cleanly into a mold, we will discuss below general characteristics which typically hold true, although it can still be difficult for patients and providers to understand the differences. There are some slight differences between the structures of the common MCOs and we will cover them below after going through a brief history of managed care in the US.

History of Managed Care in the US

Unlike traditional indemnity plans which only provided care when someone was ill, managed care looked to provide additional services and maintain a person’s health. While managed care can trace its origins in the United State to at least 1929 in Oklahoma, when Dr. Michael Shadid established a health cooperative for farmers in a small community (Kane, et al, 1996), it is safe to say that it did not start to look like what we would call modern day managed care until both: 1) more money was associated with it and 2) reimbursement for care was more easily tied to it. Initially there were “prepaid health plans”, such as the Health Cooperative of Puget Sound in Seattle and the Kaiser-Permanente Medical Program in the 1940s. Customers paid flat annual fee, the pre-paid organization in turn paid physicians on a salary to provide prepaid care (Glickstein, 1998). The American Medical Association (AMA) did not like these types of organizations and took every opportunity to make them sound bad or use the courts against them (Hendricks, 1998). However, they remained quite popular with the people and enrollment remained quite large.

The term “Health Maintenance Organization” (HMO) wasn’t actually coined until 1970, but by then demand for these types of organizations was increasing among the general population. Under the Nixon Administration, the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 amended the Public Health Service Act of 1944 and eventually provided systematic financial reimbursement methods for managed care organizations (Fox & Kongstvedt, 2013). It was also an attempt to preempt efforts by congressional Democrats to enact a universal health care plan. It was viewed as a compromise that would hopefully satisfy all parties. By requiring employers with 25 or more employees to offer an HMO option if they offered health insurance coverage to their workers, it made it more accessible to the general population. By overriding the state laws restricting the establishment of prepaid health plans and allocating funds it enabled greater competition within health care markets, this would lead to for-profit health care corporations entering a sector which had previously been dominated by non-profits. This was what the Republicans wanted (Mitchell, 1999).

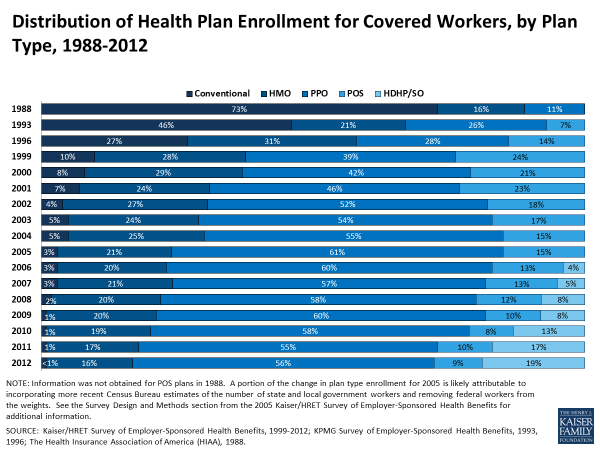

There was a surge in HMO enrollment in the 1980s and early 1990s, as well as other managed care organizations which appeared. However, a backlash soon appeared in the 1990s and early 2000s. A majority (51%) of Americans felt that managed care had decreased the quality of care for sick individuals and the majority (55%) also felt that HMOs and other managed care organizations did not keep costs down (Blendon, et al, 1998). A significant proportion of Americans were reporting issues with their managed care providing adequate care, many had issues with the arbitrarily large amount of power held by these monolithic organizations managing one’s health care, and the repeated “atrocity-type anecdotes” being circulated contributed to the rhetoric around the backlash (Mechanic, 2001). In fact, it did not actually matter how well their managed care plan was actually preforming or covering costs, there was a perception and fear from the public that they would be unable to get care or pay for it if they were to fall ill (Blendon, et al, 1998). At the crux of it, the main issues for many revolved around both the lack of choice (Duijmelinck & van de Ven, 2016) and the increasing healthcare costs (Bes, et al, 2017). This backlash led to canceling some of the cost containment methods from managed care organizations (Mays, et al, 2004) and increased enrollments, at least initially, in types other than HMOs (Cooper, et al, 2006).

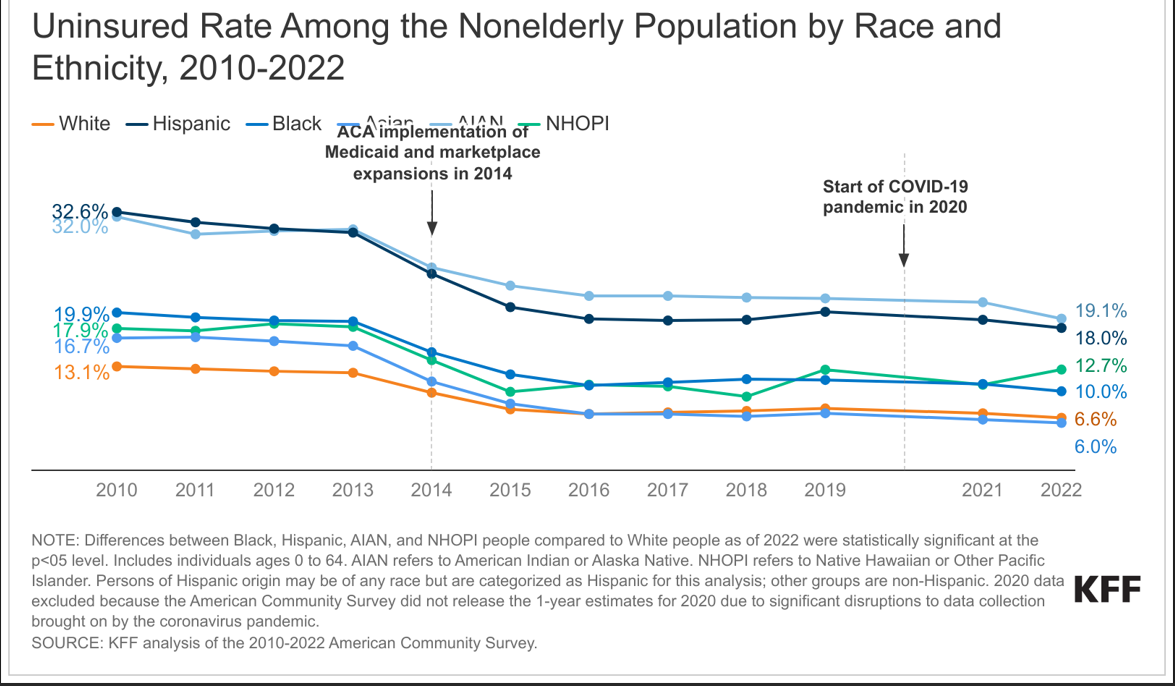

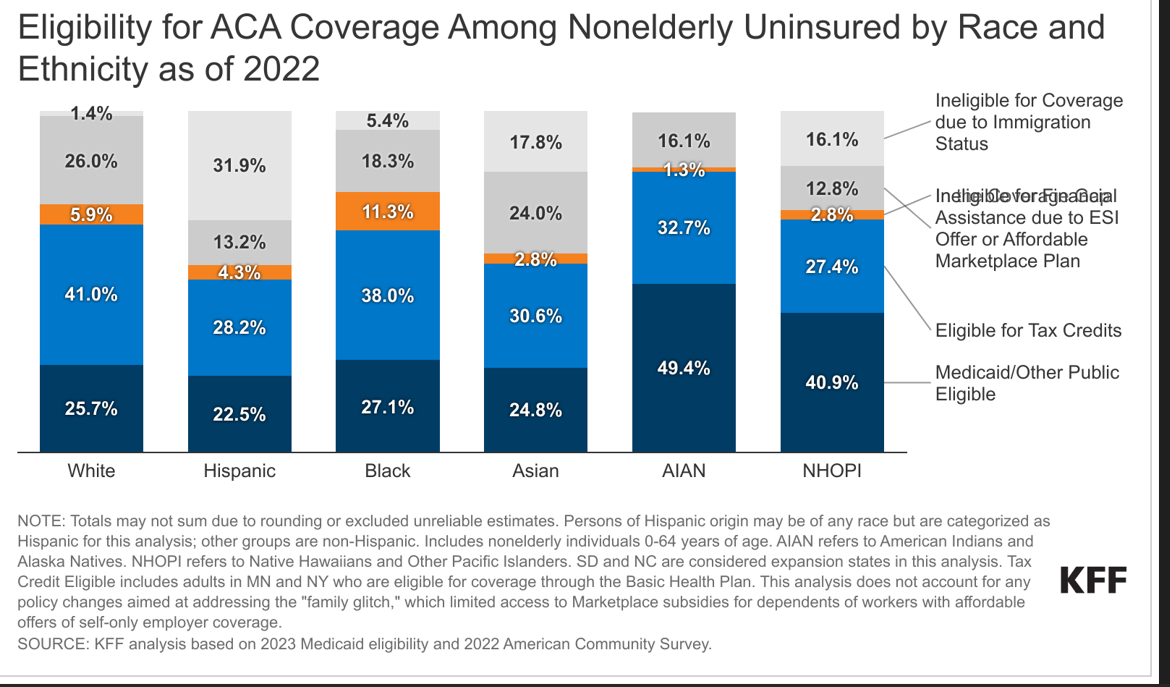

Both the Affordable Care Act and the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on the types and rate of insurance coverage which also impacted MCOs greatly.

Knowledge Check: What act signed by President Nixon increased access to MCOs for the general American public?

There are four main types of MCOs which we will cover. The first type of MCO that we will discuss is the Health Maintenance Organization (HMO):

Health Maintenance Organizations

Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) are typically defined by two features: the requirement of a designated gatekeeper and the restriction to in-network providers under normal circumstances. A gatekeeper is a Primary Care Provider (PCP) who is responsible for the preventative care screenings, routine physicals, and other primary care services. They are called a gatekeeper because the patient must first see the gatekeeper in order to obtain referrals to specialists. The idea is to keep the more expensive specialists reserved for conditions which truly cannot be handled by a primary care practitioner. The second restriction is usually very strict: health care is only covered by the insurance plan if it is given by a hospital or provider who is in network, otherwise the patient is completely financially responsible. The only exception is typically for emergency room care, where a patient cannot be reasonably expected to verify in-network status. HMOS are generally the cheapest MCO (Falkson & Srinivasan (2022)

There are four common models of HMO organizations: group, independent practice association (IPA), network, and staff.

Group Model

In the group model, the HMO contracts with a single, multispecialty entity for providers to provide care to its members. The HMO likely contracts additionally with a hospital in order to be able to provide comprehensive care to its members. The HMO pays the medical group a negotiated, per capita rate, which the group distributes among its physicians, usually on a salaried basis.

Independent Practice Association (IPA) Model

This set up is closest to the original pre-paid plans mentioned above. An IPA is a group of independent practitioners and group providers who decide to form a legal contract with a separate legal entity, known as the IPA. This IPA then contracts with the HMO to negotiate the administrative and logistical details of any arrangement, as well as some of the financial risk. That is part of why this model is so appealing to providers (Gold, 1999).

Network Model

In this model the HMO contracts with multiple provider groups, either single or multispecialty, to provide services to its members.

Staff Model

This model involves the HMO directly employing providers on a salary basis. Typically, the HMO employs physicians in a range of specialties in order to more fully serve its patients in its own facilities. HMOs often find this appealing because they exert a great deal of control directly over the physicians. This is also known as a closed-panel HMO.

Payment for HMOs

On the patient side there are premiums, which are fees that must be paid an annual or monthly basis. This enrolls the patient in the plan. When incurring medical costs, the first portion of the medical bill goes towards the deductible, the first portion of the medical bills sustained which the patient must pay out-of-pocket before the insurance will pay for anything. The next fee possibly encountered is the copay. This is a flat fee (e.g. $35 for every primary care visit) which is paid out of pocket by the patient for a set service. The final out-of-pocket expenditure is coinsurance. This is a percentage of the remaining balance that must be paid by the patient (e.g. the HMO will pay 80% of the procedure and the patient must pay the remaining 20%).

On the HMO side, they pay providers typically though salary or capitation. Capitation is a situation where a fixed sum of money is paid per time unit (usually monthly) per patient being treated by the provider. For example, a physician in the HMO with 100 patients designating her as their Primary Care Provider would receive a fixed sum of money for each of those 100 patients each month.

Preferred Provider Organizations

Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs) provide the patients with quite a bit more choice. There is no gatekeeper in a PPO. The next different feature is that there are different coverage tiers, with patients allowed to go in-network and out-of-network to providers and still receive insurance coverage. However, by going out-of-network, they would incur larger costs such as higher deductibles or higher coinsurance rates. This makes PPOs open panel. Open panel plans mean a the MCO provides incentives for the patients to use participating, or in-network, providers and but also allows patients to use providers that are out-of-network.

Local PPOs are a PPO that has a small service area and are open to beneficiaries who live in specified counties, much like most HMOs.

Regional PPOs are much larger and contract with an entire region. Regional PPOs are required to serve areas defined by one or more states with a uniform benefit package across the service area. They have gained limited traction nationally and employers prefer local PPOs, although they are somewhat popular in the smaller states (Jacobson, et al, 2017).

Typically, instead of paying providers with a capitation fee schedule, PPOs negotiate fee discounts with providers. Within the same hospital, the same procedure may be up to 31% cheaper than the average cost depending on the insurer (Craig, et al, 2021).

Point of Service (POS)

In the evolution of MCOs, Point of Service Organizations (POSs) are essentially trying to combine the costs saving aspects of the HMOs with the increased flexibility of choosing providers that a PPO has. Under this structure the patient has a gatekeeper, usually a primary care provider, who fulfills the same role by being, as the name implies, an initial point of service, for the patient. The patient is also responsible for getting referrals to specialists from this gatekeeper.

Exclusive Provider Organizations (EPO)

Exclusive Provider Organizations (EPOs) are somewhat like HMOs in that they only pay for in-network costs and all out of network costs are the responsibility of the patient. However, unlike HMOs, they do not require a gatekeeper and patients are not required to get referrals to see other in-network providers.

Table 1.

A comparison of traditional MCOs

|

MCO |

HMO |

PPO |

POS |

EPO |

|

Gatekeeper |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Out of network costs patient responsibility |

X |

|

|

X |

Knowledge Check

What is the biggest difference between an HMO and a PPO?

Evaluation of Managed Care Approaches

Chronic Disease Management

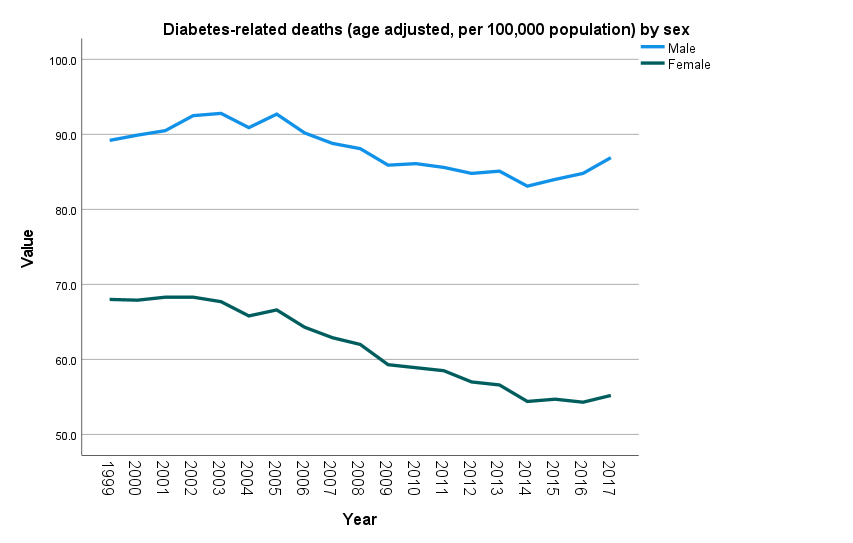

Chronic diseases and their management have become a trademark of the American healthcare system. A chronic disease is one which is defined as “a physical or mental health condition that lasts more than one year and causes functional restrictions or requires ongoing monitoring or treatment” (Raghupathi & Raghupathi, 2018). Six in ten American adults have a chronic disease and four in ten have two more more (About Chronic Diseases, 2019). Chronic conditions are the leading cause of death and disability in the country (Comlossy, 2013). More than two thirds of all deaths in the US are caused by one or more of the leading five chronic conditions (heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes) (Raghupathi & Raghupathi, 2018). Chronic diseases don’t just take their toll in terms of deaths, but also in monetary impact on the system. The top 5% of patients spending-wise with four or more chronic diseases are responsible for an annual mean expenditure of $78,198 per patient, compared to the top 5% of patients with no chronic diseases being responsible for a mean expenditure of $13,132 per patient (Cohen, 2014). Chronic diseases constitute over 70% of aggregated healthcare spending (approximately $5,300 per person annually) (Raghupathi & Raghupathi, 2018). Patients with 6 or more chronic conditions make up about 14% of Medicare recipients, but account for over half of the Medicare annual spending annually (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2012). Chronic diseases are made even more difficult to manage because they are typically the result of a confluence of social, environmental, and personal factors. This explains why certain regions are known for their chronic conditions, such as the “Diabetes Belt” in the American south (Myers, et al, 2017) which overlaps greatly with the “Stroke Belt” (Howard & Howard, 2020). They are very much related to the health of the population in which the individual is embedded. This is why a systematic and population health approach is needed to effectively prevent, manage, and treat chronic conditions. Care coordination is often how they attempt to keep costs down.

Data Source: Bridged-race Population Estimates; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau (CDC/NCHS and Census) National Vital Statistics System-Mortality (NVSS-M); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (CDC/NCHS) Accessed [May 11, 2022]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020/hp2020-errata-page.htm

Chronic Care Management (CCM)

Chronic Care Management takes a broader approach that encompasses the overall care needs of individuals with multiple chronic conditions, addressing not only medical aspects but also social, psychological, and functional aspects of care (Agarwal, et al, 2020). It is a much more holistic term, with the goal to coordinate whole body care for those with chronic conditions (Ljungholm, et al, 2022). The primary goal of CCM is to improve health outcomes and enhance the quality of life for patients with chronic illnesses by addressing their complex and often multifaceted healthcare needs. To be eligible for Medicare CCM, patients must present with multiple (two or more) chronic conditions expected to last at least 12 months or until the death of the patient. Additionally, the chronic conditions must place patients at significant risk of death, acute exacerbation or decompensation, or functional decline. Services include interactions with patients by telephone or secure email to review medical records and test results or provide self-management education and support (Rural Health Information Hub, 2022).

Knowledge Check

What is the difference between Chronic Disease Management and Chronic Care Management?

Care Coordination and the Affordable Care Act

Care coordination is particularly important in our modern society, where patients frequently seek care from multiple sources. A prime example of this is the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) spending 10% of its total health budget on care provided to Veterans outside of the VHA’s network of providers (Dixon, Haggstrom & Weiner, 2015). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) considers care coordination an interdisciplinary approach to linking patients to resources in their community and integrating social, financial, and health services in a cost-effective manner while also factoring in individual patient preferences and needs (AHRQ, Chapter 3, 2014).

As with many factors associated with population health models, the ACA has had a significant impact on case management. Although the concept of care coordination to help manage chronic disease (under the name “case management”) goes back decades with idea of managed care, the ACA has changed the financial incentives and refocused attention on care coordination to improve patient outcomes (Rackow & Fine, 2013). The ACA’s emphasis on community-based endeavors in order to serve high-need and hard to reach populations has given life to care coordination and chronic disease management (Islam, et al, 2015).

Case Management

Although the concept and position of case manager has been around for quite a while, there has been an added emphasis on using case management in multiple healthcare settings in recent years (Putra & Sandhi, 2021). Per the Case Management Society of America, it is a ““a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation, and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs through communication and available resources to promote quality, cost-effective outcomes.” (Hudon, et al, 2018). This is a vital tool in addressing care, particularly for those with complicated conditions. They often require assistance to properly coordinate the services across all the departments, community-based providers, hospitals, clinics, and insurers just to receive adequate care (Kuo, et al, 2018). Case managers help patients navigate a complex and confusing system and help keep costs down by reducing redundant tests. Case managers can greatly help with care coordination.

Utilization review

The main goal of Utilization Review (UR) originally was to ensure quality care (Restuccia, 1995) and to make sure that the care being given is reasonable (Bean, et al, 2020). It can also be done to keep costs down or to ensure that proper protocols are being used in a fair and equitable way (Bohan, et al, 2019). Utilization review can be required by hospitals (Siyarsarai, et al, 2020), Worker’s Compensation (Bean, et al, 2020), and insurance companies (Appelbaum & Parks, 2020). In addition to ensuring quality care, it can be used to prevent fraud, waste and inappropriate care from being provided to patients (Bean, et al, 2020).

There are three main types of Utilization reviews which can be conducted.

- Prospective Utilization Review

- Concurrent Utilization Review

- Retrospective Utilization Review

When looking at these three types, the biggest difference in how they are conducted is when the review is done. Prospective UR is also sometimes Prior Authorization (Giardino, & Wadhwa, 2022). It is done prior to the medical services or procedures being delivered. Concurrent UR is conducted while the medical services are ongoing. Concurrent UR is often required by Medicare or Medicaid providers and can be used to validate consumption of resources during a hospital stay (Olakunle, et al, 2011). This is used for case management instances where continuous review is necessary (Namburi & Tadi, 2022). It is also frequently associated with discharge planning to help ensure continuity of care (Smith, et al, 2020). Retrospective UR is done after the services are provided AND after the bill was delivered (Giardino, & Wadhwa, 2022).

While there are clearly some differences between these three methods, because of when they are conducted, there are many similarities between the basic procedures of these three approaches. They first check eligibility – either with the insurance plan and/or to ensure that the requested service is appropriate. If checking for appropriateness, typically they use nationally developed clinical guidelines for standards of care (Giardino, & Wadhwa, 2022). The next step is to gather clinical information to determine if criteria is met for the service. It is very important that the clinical staff document everything, including the absence of things, in order for this to be successful. It may be common for clinical staff to fail to note things that look normal (so called “charting by exception”), but this can result in denials and delays during the UR process and is strongly discouraged. If the reviewer determines that the criteria are met, the provider will be notified of approval. If not, the provider and the patient will be notified of the denial, and they can appeal, usually by providing more information.

Drug Utilization Review

A specific type of utilization review is Drug Utilization Review. While there are many types of Drug utilization review, the only one we are going to cover is the commonly used money saving technique, known as a drug formulary (2018-2019 Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Professional Practice Committee, (2019). These are also used to improve patient outcomes and avoid unnecessary prescription of medications.

Triple Aim

Despite nearly every one out of five dollars spent in the US being spent on healthcare, the US consistently ranks among the worst out of industrialized countries for health outcomes, and it has only been exacerbated by COVID (Hartman, et al, 2022). The ACA borrowed heavily from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) concept of the Triple Aim: simultaneously improving patient experience of care, improving population health, and reducing the per capita costs of care (The IHI triple aim: IHI. Institute for Healthcare Improvement, n.d.). The United States stand out internationally for unusually high cost and poor outcomes among industrialized countries (Schneider, et al, 2021), resulting in intense focus on quality. Utilizing this framework, The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) were authorized to specify quality measures which would best advance the National Quality strategic objective and build upon the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting infrastructure (Aroh, et al, 2015). This helped lead to the more formal establishment and proliferation of different types of MCOs.

More Recent Managed Care Approaches

Value Based Purchasing

Historically, the healthcare system was based on a “fee for service” model. More recently the industry has been moving towards reimbursing for quality instead of quantity due to an evolution under the ACA with reimbursement (Chee, et al 2016). This works how you would think it would – you would pay for each item or service utilized. While there have been many different payment schemes under Medicare over the years, Value Based Purchasing (VBP) (sometimes referred to as Value Based Contracting (VBC)) is one of the newest and most drastic shifts in the way of thinking about reimbursing medical care. Now the idea is to pay for value, as defined by improving outcomes and quality, reducing costs, or both at the same time (Chee, et al, 2016). You may also see this phrased as “quality over quantity” (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2021). It applies to most acute-care hospitals.

The concept of VBP can refer to a wide range of payment strategies, but the unifying link is that it ties the patient’s outcome and/or the provider’s performance to the eventual reimbursement. This can either be through a bundled payment or through a Pay for Performance (P4P) scheme (Aroh, et al, 2015). The ACA mandated a focus on quality, laying a focus for VBP to take shape and for new structures in managed care to take center stage. The COVID-19 pandemic and the corresponding rapid growth in national health expenditure has led to increased interest in this payment model from all parties, not just CMS (Shrank, et al, 2021).

Knowledge Check

What are the two types of reimbursement under Value Based Purchasing?

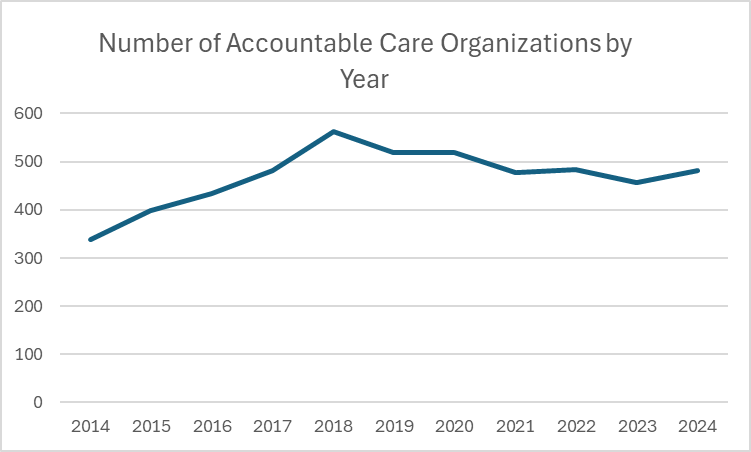

Accountable Care Organizations

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) also known as Medical Neighborhoods are relatively new MCOs on the national level. As of January 2022, there are 483 Medicare ACOs serving over 11 million beneficiaries (National Association of ACOs, n.d.). ACOs are groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers, who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high-quality care. While most ACOs are Medicare plans, there are some private ACOs (Accountable care organizations: AHA. American Hospital Association. (n.d.). As with all managed care, the goal is to coordinate care. The goal of providing better coordinated care is to ensure get the patients get the right care at the right time. It is also to avoid unnecessary duplication of services and prevent medical errors. Since 2012, ACOs have saved Medicare $13.3 billion in gross savings (National Association of ACOs, n.d.).

ACOs allow physicians, hospitals, and other clinicians and health care organizations to work more effectively together to both improve quality and slow spending growth by allowing for coordination of care among all the different providers needed to fully care for the whole person.

There are three core principles to Affordable Care Organizations:

- Provider-led organizations with a strong base of primary care that is accountable for quality and per capita costs

- Payments linked to improvement in quality and reduced costs

- Reliable and increasingly sophisticated measurement of performance, to support improvement and provide confidence care is improved, and cost savings occur. (Moy, et al, 2022).

The ACA created the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) in part to help address the fragmented nature, lack of coordination, and confusion that multiple payors can create (Berwick, 2011). Under the ACA, the ACO is accountable for the cost and the quality of the care provided. As of January 2022, there were 483 ACOs with over half a million clinicians providing care to 11 million beneficiaries participating in MSSP (Physicians Advocacy Institute, n.d.).

There are multiple “tracks” in the MSSP program which ACOs can choose, with increasing levels of risk/reward, depending on how confident the ACO is that it can improve the health of the population it is serving. We won’t go into the details of the tracks – but we will summarize the arrangements as this: If they can save money by improving the health of the population (thereby avoiding costs) for both themselves and Medicare, the ACO will get to share in a percentage of the saved costs. This will be determined by a benchmark to itself during an initial period. However, if the ACO fails to reach these goals, it will receive a penalty in the form of having its reimbursement cut by a certain, agreed upon percentage. Because this is reimbursing for clinical outcomes, this is an example of Pay for Performance (P4P).

Another form of reimbursement ACOs can receive is Bundled Payments (Navathe, et al, 2020). The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (Innovation Center) created the Bundled Payment Care Initiative (BPCI) as a new way of linking payments for an episode of care (Agarwal, et al, 2020). Instead of taking the payments from each individual provider separately, it links all of the various providers together for one single payment. One of the differences with bundled payments is that it shifts the clinical and financial responsibility on providers to a single care episode for an individual instead of the current set up of making reimbursement tied to ongoing outcomes. For example, instead of each portion and provider involved with a knee replacement billing separately, the ACO would simply bill for a single bundled payment. If the providers are about to coordinate care effectively and keep the total care costs for the knee replacement below the bundled payment reimbursement amount, they are able to generate a profit. However, if they are unable to do that and the costs exceed the bundled payment amount, they all incur a financial loss. Studies show that it maintains or improves quality while lowering cost for lower extremities but does not seem to be as effective at other conditions or procedures (Agarwal, et al, 2020).

Data Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed [May 11, 2022]. Available from https://healthdata.gov/dataset/Accountable-Care-Organizations/74pg-c9d8

Patient Centered Medical Homes

The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) concept was originally introduced in 1967 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2007 the concept was further refined into a set of principles by four primary care physician organizations, including the: American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. PCMHs are sometimes confused with ACOs, but they are quite different. PCMHs are basically a multidisciplinary approach to primary care delivery. (Hong, et al, 2018). The ACA allowed for special funding avenues for state medical homes with Medicaid beneficiaries (Davis, et al, 2011). The focus of the PCMH is to provide meaningful, holistic care of the patient, both physical and mental, via an interdisciplinary team of providers under one roof (Bresnick, 2019). Today there are a number of medical home models of care with corresponding certifications, accreditations or recognition programs. Although consensus exists around the basic components of the medical home, not all models look alike or use the same approaches to improve healthcare quality and control costs. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the attributes of a PCMH are

- Comprehensive Care

- Patient Centered

- Coordinated Care

- Accessible Services

- Quality and Safety

PCMHs were believed to hold great promise to address longstanding inequities in the quality of the primary care experienced among socially and economically marginalized populations. However, a study by Bell, et al (2021) of the geographic distribution of the country’s medical homes indicated that medical homes are more likely to emerge within communities that have more favorable health and socioeconomic conditions to begin with. Despite the wide adoption of PCMHs, the evidence about effectiveness remains mixed. One potential explanation for these mixed findings is the wide variation in how the model is implemented by practices. Significant reductions in emergency department utilization and outpatient care, and both lab and imaging services among practices which emphasized the adoption of expanded electronic communications tools (Saynisch, et al, 2021).

The major ways in which PCMHS are financed are through 3 primary ways: increased fee-for-service (FFS) payments, traditional FFS payments with additional per-member-per-month (PMPM) payments, and traditional FFS payments with PMPM and pay-for-performance (P4P) payments (Basu, et al, 2016).

Knowledge Check: What is the difference between an ACO and a PCMH?

Telehealth changes after COIVD

Telehealth has historically had relatively slow adoption and approval for reimbursement from payers. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, due to the closing of many physical locations, we saw for the first-time payment parity for telehealth visits and in person visits from multiple payors, including Medicare (Shachar, et al, 2020). Payment parity was viewed as a critical step, resulting in the proportion of telehealth visits going from 10% before the pandemic to more than 90% telehealth work during the pandemic (Lonergan, et al, 2020). In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, many states as well as Medicare made changes to their telehealth policies. For example, the states of New Mexico, Ohio, and Texas required special telehealth licenses in order to offer these services prior to the pandemic, but relaxed these requirements during COVID (Shachar, et al, 2020). The office of Office for Civil Rights at the Department of Health and Human Services also announced that they would not impose penalties for HIPAA violations that occur during the good faith provision of telehealth during the COVID-19 emergency, which allowed providers to use platforms that were not HIPAA compliant (Shachar, et al, 2020).

Some of these have been permeant changes, such as Medicare allowing Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) to provide remote behavioral/mental health services. Patients can now receive these services at home without geographical limitations. Additionally, audio-only communication platforms are approved for delivering such services, and Rural Emergency Hospitals (REHs) are now eligible sites for telehealth. Some of the changes at the federal level are temporary though, such as FQHCs and RHCs being allowed to offer remote non-behavioral/mental health services, and waiving the requirement of an in-person visit within the last six-months to initiate behavioral/mental telehealth, until December 31, 2024 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2023). Currently with Medicaid fee-for-service, most states and Washington DC reimburse for live video, store-and-forward, remote patient monitoring (RPM), and audio-only telephone services, albeit with various limitations. Specifically, 25 states cover all four modalities, but often with restrictions. Additionally, 43 states, DC, and the Virgin Islands have laws concerning telehealth reimbursement for private payers, but only 24 states explicitly mandate payment parity (CCHP, 2023).

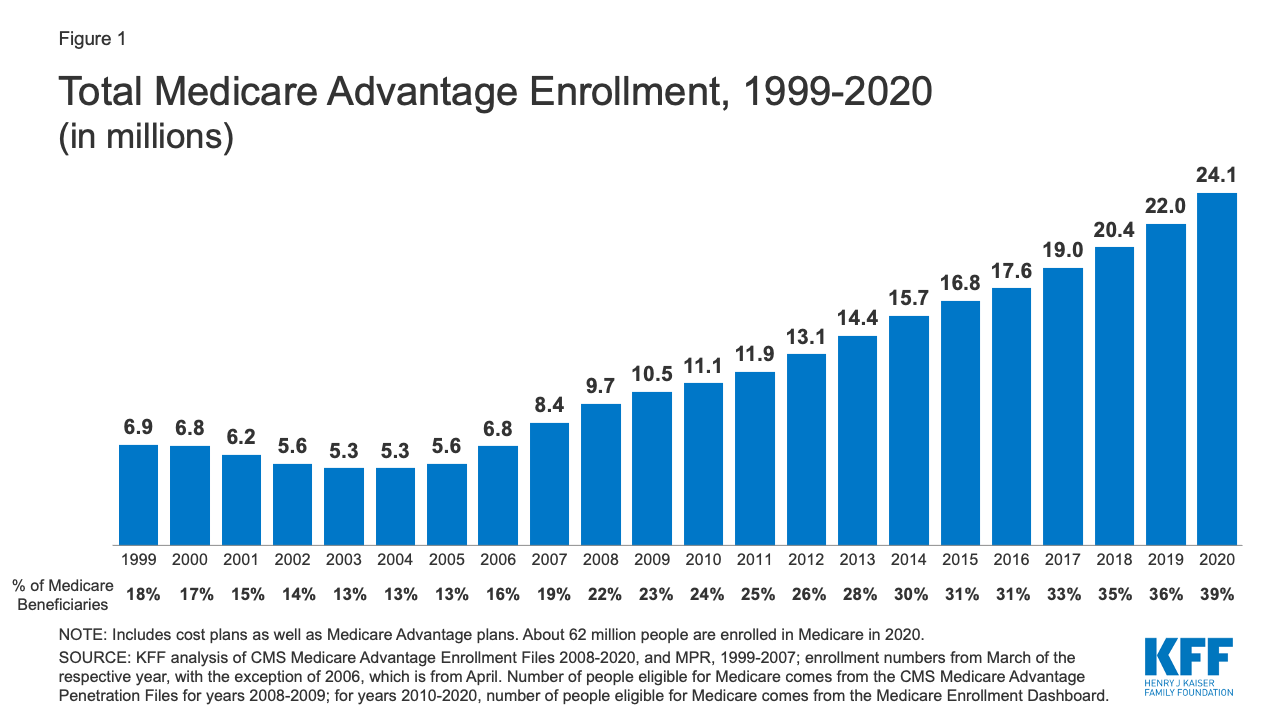

Medicare Advantage

Medicare Advantage is a bundled or managed alternative to traditional Medicare. Private insurers that offer Medicare Advantage plans contract with the federal government to provide health insurance benefits to people who qualify for Medicare. Medicare Advantage Plans, also known as Medicare Part C or MA plans are a substitute for Medicare parts A and B and most also include drug coverage (Part D). (Medicare.gov, n.d.), Medicare-approved private companies must adhere to the rules set by Medicare (Geyman, 2022). The most common types of Medicare Advantage Plans are HMO Plans, PPO Plans, Private Fee-for-Service (PFFS) Plans, and Special Needs Plans (SNPs) (Medicare.gov, n.d.). Patients in the SNPs are parts of specific subgroups of high-need Medicare beneficiaries. The SNP plans receive risk-adjusted capitated payments and are responsible for providing coordinated care services for these patients (Powers, et al, 2020).

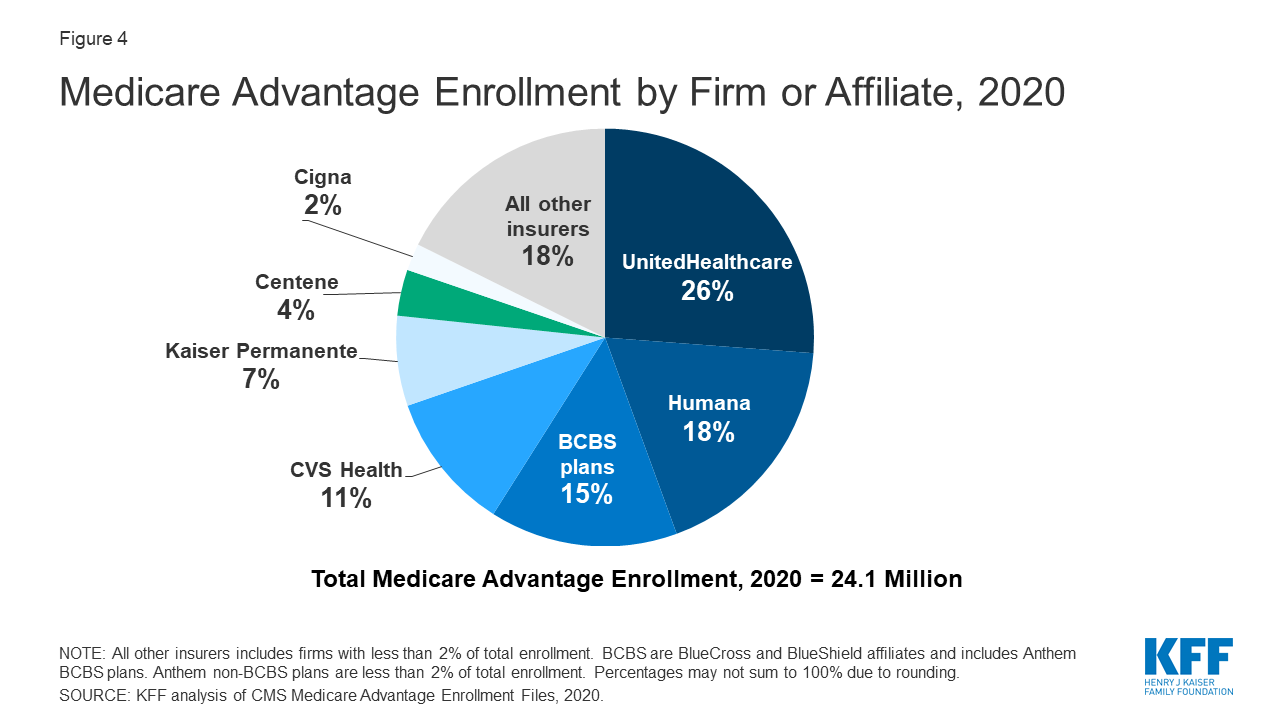

MA plan enrollment is growing much faster than that of traditional Medicare. In 2020, nearly four in ten (39%) of all Medicare beneficiaries – 24.1 million people out of 62.0 million Medicare beneficiaries overall – were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the share of all Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans will rise to about 51% by 2030 (Martin et al., 2020).

Medicare Advantage enrollment is highly concentrated among a small number of firms. UnitedHealthcare and Humana together account for 44% of all Medicare Advantage enrollees nationwide, and the BCBS affiliates (including Anthem BCBS plans) account for another 15% of enrollment in 2020. Another four firms (CVS Health, Kaiser Permanente, Centene, and Cigna) account for 23% of enrollment in 2020 (KKK, 2019).

MA plans offer beneficiaries a better deal than traditional Medicare. Instead of having to buy a Medigap plan to cover costs that traditional Medicare doesn’t cover, as well as a Part D prescription drug plan, MA enrollees pay only a small monthly premium, and 56% pay no premium on top of their Medicare Part B premium. In many plans, some level of dental, vision, and hearing coverage is included, which is missing in traditional Medicare (Willink, et al., 2020). In April 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued new rules permitting Medicare Advantage plans to expand the types of supplemental benefits that can be offered to enrollees. Subsequently, MA plans have begun to offer additional benefits, such as transportation to the doctor, home-delivered meals for those recently discharged from the hospital, and some personal care in the home (Meyers, et al., 2019). None of these benefits are included with traditional Medicare.

On the other hand, MA networks are restricted, and some are very limited. In 2015, 35% of MA enrollees were in plans with narrow physician networks. Although recent research shows that most MA members have broad access to primary care doctors. MA enrollees who become seriously ill may have to pay significant fees to out-of-network specialty providers (Jacobson et al, 2019).

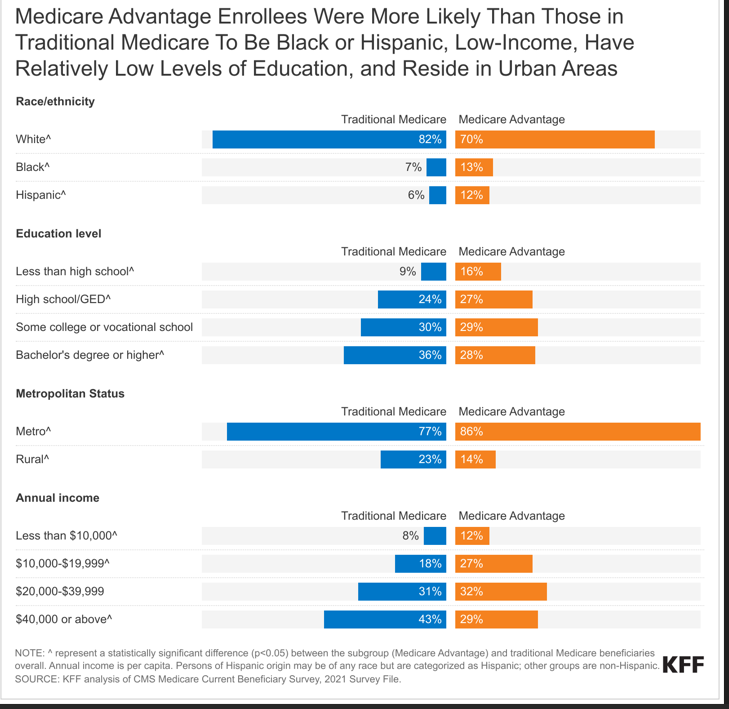

It has not been definitively determined whether MA offers better quality of care for beneficiaries than traditional Medicare. A number of studies suggest that it does in areas such as diabetes care, (Landon, et al, 2015), quality measures and patient satisfaction (Timbie et al, 2017), and fewer inpatient stays and emergency department visits (Avalere, 2017). A recent study of 47,100 Medicare beneficiaries found that Medicare Advantage plans may achieve lower health care utilization through high efficiency of care rather than under provision of care (Park, et al, 2020). However, Medicare beneficiaries who had been hospitalized at least once, used home health care or long-term nursing home care had a higher rate of switching back to traditional Medicare than did other MA enrollees (Rahman, 2015). There are some demographic differences between Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage recipients. This can be a partial explanation for differing patterns of healthcare use between the two populations (Agarwal, et al, 2021).

Certification and Accreditations

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) is a voluntary accreditation agency which evaluates MCOs (McIntyre, et al, 2001). NCQA health plan accreditation is considered a gold standard and a commitment to quality NCQA. (n.d.). The NCQA developed the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) to assess clinical care ranging from effectiveness, availability, utilization, and quality of clinical care. It includes 90 measures over 6 domains of care. The data generated from HEDIS has been instrumental in evaluating the effectiveness of various health care plans. It is one of the most widely used tools in performance improvement, as over 191 million people are enrolled in in plans that report to HEDIS (NCQA, 2022).

For utilization review, the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission (URAC) is a voluntary agency which evaluates agencies and health plans for adhering to rigorous standards of utilization review (Accreditation Standards. URAC, 2020) URAC accredits over 1,000 organizations (Accreditation’s Gold Star Standard in Health Care. URAC, 2022).

Managed Care Discussion Questions

- What are some common themes with the evolution of managed care?

- What populations might HMOs be better fitted for? PPOs? POS?

- What role does managed care have in addressing and managing chronic diseases?

- How do you think case managers help keep costs down in MCOs?

- Why is Utilization Review important to keep costs down in MCOs?

- How is Value Based Purchasing a fundamental shift from the traditional Fee For Service?

- What role do you think Health Information Technology plays in the new MCOs?

- What do you think will happen with Telehealth reimbursement in the future?

- Do some research on what is involved in an agency getting certified. Does it always make sense for agencies to get certified?

Student resources

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality – https://www.ahrq.gov

AHRQ, Self-Management Support: https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/self-mgmt/what.html

American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA), Revenue Cycle Resources: https://www.ahima.org/education-events/education-by-topic/revenue-cycle/

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Innovation Center – https://innovation.cms.gov

Certified Managed Care Nurse (CMCN) Home Study Course, American Association of Managed Care Nurses (AAMCN) : https://aamcn.org/home_study.html

Connected Care Toolkit: https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/Downloads/connected-hcptoolkit.pdf

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP): https://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/index.html

Healthcare.Gov Find Local Help – https://localhelp.healthcare.gov/

Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA) online learning: https://learn.hfma.org/catalog?labels=%5B%22Content%20Type%22%5D&values=%5B%22Course%22%5D&_gl=1*1bo9ztm*_ga*NTI1ODIyNDg5LjE3MDg5MDMxNzQ.*_ga_6L872WMCZ1*MTcwODkwMzE3NC4xLjEuMTcwODkwMzI1OC4wLjAuMA..

HealthData.gov – https://www.healthdata.gov

Healthy People 2030 – https://health.gov/healthypeople

Institute for Healthcare Improvement: http://www.ihi.org/

Kaiser Family Foundation Medicaid Managed Care Tracker – https://www.kff.org/statedata/collection/medicaid-managed-care-tracker/

Managed Healthcare Executive: https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/

Medicare Learning Network (MLN): https://www.cms.gov/training-education/medicare-learning-network/resources-training

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA): https://www.ncqa.org/

Telehealth Policy Across the U.S. in 2024 (video): https://youtu.be/6goKMWzOaa0

Understanding the healthcare system as a consumer, TEDx talk: https://youtu.be/lEh0g0R46Do?si=gwXa1jkXalRDHVTZ

What is an Accountable Care Organization (ACO)? HSS video: https://youtu.be/6NAqOBS3WVE?si=1lDwPBFWML9ZwJmR

Key Words

Accountable Care Organization (ACO): Also known as Medical Neighborhoods, these Managed Care Organizations are defined by the groupings of doctors, hospitals, and various providers coming together to provide coordinated care for a specific population.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The agency within the Department of Health and Human Services focused on making healthcare higher quality, more accessible, equitable, and affordable.

Capitation: A payment scheme where a provider is paid a fixed sum of money per patient per time unit.

Case Management: A process of coordinating services across the continuum of care.

Coinsurance: A percentage of a balance on a medical bill which must be paid by the patient.

Copay: A flat fee that the patient pays out of pocket for set services.

Deductible: The first portion of a medical bill which must be paid out of pocket by a patient before insurance pays.

Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO): A type of Managed Care Organization that is defined by the lack of a gatekeeper and only covers in-network providers

Gatekeeper: A primary care provider who is responsible for screening patient populations in certain MCOs before they see specialists.

Health Maintenance Organization (HMO): A type of Managed Care Organization that is defined by the features of a gatekeep and the requirement of the use of in-network providers.

Managed Care Organization (MCO): An organization that provides integrated and coordinated care to a patient population with the goal of keeping costs down while maintaining high quality care.

Medicare Advantage Plans (MA Plans): Also known as Medicare Part C, these are bundled or managed alternative to Medicare. These plans typically offer supplemental coverage perks that Medicare Parts A & B do not.

The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH): A managed care organization that is a single agency providing holistic coordinated care with an interdisciplinary team.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA): Often colloquially referred to as “Obamacare”, was a comprehensive healthcare reform law enacted March 23, 2010, which had a great impact on managed care. It mandated a focus on quality and laid the groundwork for new reimbursement methods including Value Based Purchasing to be widespread.

Point of Service (POS): A type of Managed Care Organization that is defined by the use of a gatekeeper and two tiers of coverage: in-network at a higher coverage rate and out-of-network at a lower coverage rate.

Preferred Provider Organization (PPO): A type of Managed Care Organization that is defined by the lack of a gatekeeper and two tiers of coverage: in-network at a higher coverage rate and out-of-network at a lower coverage rate.

Premium: A fee which is paid on an annual or monthly basis to enroll a patient in a managed care plan.

The Triple Aim: Created by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the Triple aim is to : simultaneously improving patient experience of care, improving population heath, and reducing the per capita costs of care. It was heavily borrowed from when the ACA was created and helped lead to the establishment of new reimbursement methods.

Utilization review (UR): The process of reviewing what medical services or goods are being or have been ordered. It can be done to ensure proper protocol is adhered to, to keep costs down, to prevent waste, etc. There are multiple types of UR and it can be applied in many settings.

Value Based Purchasing (VBP): Sometimes referred to as Value Based Contracting (VBC), this is the process of reimbursing for “quality over quantity”. It covers a wide range of payment strategies, but they all tie patient outcomes to provider reimbursement.

References

2018-2019 Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Professional Practice Committee. (2019). Prior authorization and utilization management concepts in managed care pharmacy. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 25(6), 641-644.

About Chronic Diseases. (2019, October 23). Retrieved March, 10, 2022 from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm

Accountable care organizations: AHA. American Hospital Association. (n.d.). Retrieved March 8, 2022, from https://www.aha.org/accountable-care-organizations-acos/accountable-care-organizations

Accreditation Standards. URAC. (2020, November 29). Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://www.urac.org/accreditations-certifications/accreditation-standards/

Accreditation’s Gold Star Standard in Health Care. URAC. (2022, January 14). Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://www.urac.org/#:~:text=Accreditation%20and%20Certification%20Directories,care%20organizations%20through%20its%20programs.

The Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care. (n.d.). Why accreditation for your non-profit organization … – AAAHC. A Guide for Managed Care Organization Accreditation. Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://eweb.aaahc.org/eWeb/docs/GuideForMCO.pdf

Agarwal, S. D., Barnett, M. L., Souza, J., & Landon, B. E. (2020). Medicare’s Care Management Codes Might Not Support Primary Care As Expected: An analysis of rates of adoption for Medicare’s new billing codes for transitional care management and chronic care management. Health Affairs, 39(5), 828-836.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2014). AHRQ Updates On Primary Care Research: The AHRQ Patient-Centered Medical Home Resource Center. The Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 586-586. Doi:10.1370/afm.1728

Appelbaum, P. S., & Parks, J. (2020). Holding insurers accountable for parity in coverage of mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services, 71(2), 202-204.

Agarwal, R., Liao, J. M., Gupta, A., & Navathe, A. S. (2020). The Impact Of Bundled Payment On Health Care Spending, Utilization, And Quality: A Systematic Review: A systematic review of the impact on spending, utilization, and quality outcomes from three Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services bundled payment programs. Health Affairs, 39(1), 50-57.

Agarwal, R., Connolly, J., Gupta, S., & Navathe, A. S. (2021). Comparing Medicare Advantage And Traditional Medicare: A Systematic Review: A systematic review compares Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare on key metrics including preventive care visits, hospital admissions, and emergency room visits. Health Affairs, 40(6), 937-944.

Aroh, D., Colella, J., Douglas, C., & Eddings, A. (2015). An Example of Translating Value-Based Purchasing Into Value-Based Care. Urologic nursing, 35(2), 61-74.

Avelere, (2017). Medicare Advantage achieves better health outcomes and lower utilization of high-cost services compared to Fee-for-Service Medicare. Retrieved April 18. 2022 from https://img04.en25.com/Web/AvalereHealth/%7B914072d2-41c3-4645-84e0-2ac8f761be2e%7D_BMA_Report.pdf.

Basu, S., Phillips, R. S., Song, Z., Landon, B. E., & Bitton, A. (2016). Effects of new funding models for patient-centered medical homes on primary care practice finances and services: results of a microsimulation model. The Annals of Family Medicine, 14(5), 404-414.

Bean, M., Erdil, M., Blink, R., McKinney, D., & Seidner, A. (2020). Utilization Review in Workers’ Compensation: Review of Current Status and Recommendations for Future Improvement. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(6), e273-e286.

Bell, N., Wilkerson, R., Mayfield-Smith, K., & Lòpez-De Fede, A. (2021). Community social determinants and health outcomes drive availability of patient-centered medical homes. Health & Place, 67, 102439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102439.

Berwick, D. M. (2011). Launching accountable care organizations—the proposed rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(16), e32.

Berwick, D. M., Nolan, T. W., & Whittington, J. (2008). The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health affairs, 27(3), 759-769.

Bes, R. E., Curfs, E. C., Groenewegen, P. P., & de Jong, J. D. (2017). Selective contracting and channeling patients to preferred providers: a scoping review. Health Policy, 121(5), 504-514.

Blendon, R. J., Brodie, M., Benson, J. M., Altman, D. E., Levitt, L., Hoff, T., & Hugick, L. (1998). Understanding The Managed Care Backlash: Regardless of how well their plans perform today, people in managed care have greater fears than their traditionally insured peers do that their plan will fall short when they really need it. Health Affairs, 17(4), 80-94.

Bohan, J. G., Madaras-Kelly, K., Pontefract, B., Jones, M., Neuhauser, M. M., Goetz, M. B., … & Cunningham, F. (2019). Evaluation of uncomplicated acute respiratory tract infection management in veterans: a national utilization review. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 40(4), 438-446.

Bresnick, J. (2019, December 18). Breaking down the basics of the patient-centered medical home. Breaking Down the Basics of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://healthitanalytics.com/features/breaking-down-the-basics-of-the-patient-centered-medical-home

CCHP. (2023, October 23). State telehealth laws and reimbursement policies report, fall 2023. State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies Report, Fall 2023. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/state-telehealth-laws-and-reimbursement-policies-report-fall-2023-2/

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic Conditions among Medicare Beneficiaries, Chartbook, 2012 Edition. Baltimore, MD. 2012.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021, December 1). Hospital value-based purchasing. The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program. Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/HVBP/Hospital-Value-Based-Purchasing

Chee, T. T., Ryan, A. M., Wasfy, J. H., & Borden, W. B. (2016). Current state of value-based purchasing programs. Circulation, 133(22), 2197-2205.

Cohen, S. B. (2014, September). Statistical Brief #448: Differentials in the Concentration of Health Expenditures across Population Subgroups in the U.S., 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2022 from https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st448/stat448.shtml

Comlossy, M. (2013). Chronic disease prevention and management. In National Conference of State Legislatures (pp. 1-16).

Cooper, P. F., Simon, K. I., & Vistnes, J. (2006). A closer look at the managed care backlash. Medical Care, 44: I4-I11.

Craig, S. V., Ericson, K. M., & Starc, A. (2021). How important is price variation between health insurers?. Journal of Health Economics, 77, 102423.

Cutler, D. (2013, November 13). The health-care law’s success story: Slowing down medical costs. Washington Post. Washington Post. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-health-care-laws-success-story-slowing-down-medical-costs/2013/11/08/e08cc52a-47c1-11e3-b6f8-3782ff6cb769_story.html.

Davis, K., Abrams, M., & Stremikis, K. (2011). How the Affordable Care Act will strengthen the nation’s primary care foundation. Journal of general internal medicine, 26(10), 1201-1203.

Dixon, B. E., Haggstrom, D. A., & Weiner, M. (2015). Implications for informatics given expanding access to care for Veterans and other populations. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(4), 917-920.

Donabedian, A. (1988). Quality assessment and assurance: unity of purpose, diversity of means. Inquiry, 25: 173-192.

Duijmelinck, D., & van de Ven, W. (2016). What can Europe learn from the managed care backlash in the United States? Health Policy, 120(5), 509-518.

Falkson, S. R., & Srinivasan, V. N. (2022). Health Maintenance Organization. In Statpearls. essay, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Fox, P. D., & Kongstvedt, P. R. (2013). A history of managed health care and health insurance in the United States. Essentials of managed health care. Burlington, Sixth Edition: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Geyman, J. (2022). Privatized Medicare Advantage for All: The Latest Assault on US Health Care. International Journal of Health Services, 52(1), 141-145.

Giardino, A. P., & Wadhwa, R. (2022). Utilization Management. In Statpearls., StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Glickstein, D. (1998). Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound—A Short History. The Permanente Journal, 2(2), 60-61.

Gold, M. (1999). Financial incentives: current realities and challenges for physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(Suppl 1), S6-S12.

Hartman, M., Martin, A. B., Washington, B., Catlin, A., & National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. (2022). National Health Care Spending In 2020: Growth Driven By Federal Spending In Response To The COVID-19 Pandemic: National Health Expenditures study examines US health care spending in 2020. Health Affairs, 41(1), 13-25.

Heaton, J., & Tadi, P. (2022). Managed Care Organization. In Statpearls., StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Hedis. NCQA. (2022, February 22). Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/

Hendricks, R. L. (1998). To Serve the Greatest Number: A History of Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 72(2), 363-364.

Hudon, C., Chouinard, M. C., Dubois, M. F., Roberge, P., Loignon, C., Tchouaket, É., … & Bouliane, D. (2018). Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services: a mixed methods study. The Annals of Family Medicine, 16(3), 232-239.

Hong, Y. R., Huo, J., & Mainous, A. G. (2018). Care coordination management in patient-centered medical home: analysis of the 2015 Medical Organizations Survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(7), 1004-1006.

Howard, G., & Howard, V. J. (2020). Twenty years of progress toward understanding the stroke belt. Stroke, 51(3), 742-750.

The IHI triple aim: IHI. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (n.d.). Retrieved March 8, 2022, from http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx

Islam, N., Nadkarni, S. K., Zahn, D., Skillman, M., Kwon, S. C., & Trinh-Shevrin, C. (2015). Integrating community health workers within Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act implementation. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP, 21(1), 42-50.

Jacobson, G., Damico, A., Neuman, T., & Gold, M. (2017). Medicare Advantage 2017 spotlight: enrollment market update. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Jacobson, G., Rae, M., Neuman, T., Orgera, K., & Boccuti, C. (2019). Medicare Advantage: How robust are plans’ physician networks? KFF. Retrieved April 18, 2022 from https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/medicare-advantage-how-robust-are-plans-physician-networks/

Kane, R., Kane, R., Kaye, N., Mollica, R., Riley, T., Saucier, P., Snow, K., & Starr, L. (1996). Managed Care Basics. In Managed care: Handbook for the aging network. Essay, National LTC Resource Center.

KFF. (2019). Medicare Advantage. Retrieved April 17, 2022 from https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/Medicare-advantage/.

Kuo, D. Z., McAllister, J. W., Rossignol, L., Turchi, R. M., & Stille, C. J. (2018). Care coordination for children with medical complexity: whose care is it, anyway?. Pediatrics, 141(Supplement_3), S224-S232.

Landon, B., Saunders, R., Pawlson, L. G., Newhouse, J., & Ayanian, J. (2015). A comparison of relative resource use and quality in Medicare Advantage health plans versus traditional Medicare. Am J Managed Care. 2015;21(8):559-566.

Ljungholm, L., Klinga, C., Edin‐Liljegren, A., & Ekstedt, M. (2022). What matters in care continuity on the chronic care trajectory for patients and family carers?—A conceptual model. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(9-10), 1327-1338.

Lonergan, P. E., Washington Iii, S. L., Branagan, L., Gleason, N., Pruthi, R. S., Carroll, P. R., & Odisho, A. Y. (2020). Rapid utilization of telehealth in a comprehensive cancer center as a response to COVID-19: cross-sectional analysis. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(7), e19322.

Martin, A., Hartman, M., Lassman, D., & Catlin, A. (2020). National health care spending in 2019: Steady growth for the fourth consecutive year. Health Affairs 40(1). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02022.

Mays, G. P., Claxton, G., & White, J. (2004). Managed Care Rebound? Recent Changes In Health Plans’ Cost Containment Strategies: Strategies from the first wave of managed care have crept back into the practices of health plans. Health Affairs, 23(Suppl1), W4-427.

McIntyre, D., Rogers, L., & Heier, E. J. (2001). Overview, history, and objectives of performance measurement. Health Care Financing Review, 22(3), 7-21.

Mechanic, D. (2001). The managed care backlash: perceptions and rhetoric in health care policy and the potential for health care reform. The Milbank Quarterly, 79(1), 35-54.

Medicare.gov. (n.d.). Medicare Advantage Plans. Medicare. Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change-plans/types-of-medicare-health-plans/medicare-advantage-plans

Mitchell, D. (1999). Managed care & developmental disabilities: Reconciling the realities of managed care with the individual needs of persons with disabilities. High Tide Press.

Moy, H. P., Giardino, A. P., & Varacallo, M. (2022). Accountable Care Organization. In Statpearls. essay, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Meyers, D.J., Durfey S., Gadbois, E.A., & Thomas, K.S. (2019). Early adoption of new supplemental benefits by Medicare Advantage plans. JAMA. 321(22):2238–2240. Doi:10.1001/jama.2019.4709.

Myers, C. A., Slack, T., Broyles, S. T., Heymsfield, S. B., Church, T. S., & Martin, C. K. (2017). Diabetes prevalence is associated with different community factors in the diabetes belt versus the rest of the United States. Obesity, 25(2), 452-459.

National Association of ACOs. (n.d.). Home. National Association of ACOs. Retrieved March 8, 2022, from https://www.naacos.com/#:~:text=As%20of%20January%202022%2C%20there,serving%20millions%20of%20additional%20patients.

Namburi, N. & Tadi, P. (2022). Managed Care Organization. In Statpearls., StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Navathe, A. S., Dinh, C., Dykstra, S. E., Werner, R. M., & Liao, J. M. (2020). Overlap between Medicare’s voluntary bundled payment and accountable care organization programs. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 15(6), 356-359.

NCQA. (n.d.). NCQA accreditation. NCQA. Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://store.ncqa.org/accreditation.html

Olakunle, O, Brown, I. L., & Williams, K. (2011). Concurrent utilization review: Getting it right. Physician Executive, 37(3), 50-54.

Park, S., White, L., Fishman, P., Larson, E.B., & Coe N.B. (2020). Health care utilization, care satisfaction, and health status for Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with and without Alzheimer disease and related dementias. JAMA Network Open. 3(3):e201809. Doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1809.

Physicians Advocacy Institute . (n.d.). Medicare Shared Savings Program Overview. Medicare Quality Payment Program (QPP). Retrieved April 18, 2022, from http://www.physiciansadvocacyinstitute.org/Portals/0/assets/docs/Advanced-APM-Pathway/Medicare%20Shared%20Savings%20Program%20Overview.pdf

Powers, B. W., Yan, J., Zhu, J., Linn, K. A., Jain, S. H., Kowalski, J., & Navathe, A. S. (2020). The beneficial effects of Medicare advantage special needs plans for patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Affairs, 39(9), 1486-1494.

Putra, A. D. M., & Sandhi, A. (2021). Implementation of nursing case management to improve community access to care: A scoping review. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(3), 141-150.

Rackow, E.C., & Fine, C. (2013). The Affordable Care Act and Its Impact on Care Management. Journal of Aging Life Care. https://www.aginglifecarejournal.org/the-affordable-care-act-and-its-impact-on-care-management/

Raghupathi, W., & Raghupathi, V. (2018). An empirical study of chronic diseases in the United States: a visual analytics approach to public health. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(3), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030431

Rahman, M., Keohane, L., Triveda, A., & Mor, V. (2015). High-Cost patients had substantial rates of leaving Medicare Advantage and joining traditional Medicare. Health Affairs 34(10).

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0272.

Restuccia, J. D. (1995). The evolution of hospital utilization review methods in the United States. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 7(3), 253-260.

Rural Health Information Hub, Chronic Care Management. (2022). Retrieved February, 25 2024, from https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/care-management/chronic-care-management

Saynisch, P. A., David, G., Ukert, B., Agiro, A., Scholle, S. H., & Oberlander, T. (2021). Model homes: Evaluating approaches to patient-centered medical home implementation. Medical Care, 59(3), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001497

Schneider, E. C., Shah, A., Doty, M. M., Tikkanen, R., Fields, K., & Williams, R. D. (2021). Mirror Mirror 2021 Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the US Compared to Other High-Income Countries. Retrieved March 8, 2022, from https://heatinformatics.com/sites/default/files/images-videosFileContent/Schneider_Mirror_Mirror_2021.pdf

Shachar, C., Engel, J., & Elwyn, G. (2020). Implications for telehealth in a postpandemic future: regulatory and privacy issues. Jama, 323(23), 2375-2376.

Shrank, W. H., DeParle, N. A., Gottlieb, S., Jain, S. H., Orszag, P., Powers, B. W., & Wilensky, G. R. (2021). Health costs and financing: challenges and strategies for a new administration: Commentary recommends health cost, financing, and other priorities for a new US administration. Health Affairs, 40(2), 235-242.

Siyarsarai, P., Gholami, K., Nikfar, S., & Amini, S. (2020). Optimization of Health Transformation Plan by Drug Utilization Review Strategy in a Pediatric Teaching Hospital. International Journal of Pediatrics, 8(11), 12503-12515.

Smith, T. E., Haselden, M., Corbeil, T., Tang, F., Radigan, M., Essock, S. M., … & Olfson, M. (2020). Relationship between continuity of care and discharge planning after hospital psychiatric admission. Psychiatric services, 71(1), 75-78.

Timbie, J. W., Bogart, A., Damberg, C. L., Elliott, M. N., Haas, A., Gaillot, S. J., Goldstein, E. H., & Paddock, S. M. (2017). Medicare Advantage and Fee-for-Service performance on clinical quality and patient experience measures: Comparisons from three large States. Health Services Research, 52(6), 2038–2060. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12787.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, December 19). Telehealth policy changes after the COVID-19 public health emergency. telehealth.hhs.gov. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/telehealth-policy/policy-changes-after-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

Whittington, J. W., Nolan, K., Lewis, N., & Torres, T. (2015). Pursuing the triple aim: the first 7 years. The Milbank Quarterly, 93(2), 263-300.

Willink, A., Reed, N., Swenor, B., Leinbach, L., DuGoff, E., & Davis, K. (2020). Dental, vision, and hearing services: Access, spending, and coverage for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Affairs 39(2). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00451.