7

Government Programs

Raymond J. Higbea, PhD FACHE, FHFMA

Lara Jaskiewicz, PhD, MPH, MBA

Greg Cline, PhD

Grand Valley State University

“I believe the most important aspect of Medicare is not the structure of the program but the guarantee to all Americans that they will have high quality health care as they get older” – Ron Wyden

Learning Objectives

Understand the purpose and actions of the following groups:

- Government Providers

- Government Payers

- The gray zone – supporting agencies and programs

Introduction

When compared to other countries throughout the world, the role of United States federal and state government programs in healthcare is more unique for what it is not than what it is. In most other industrialized countries, the federal government is the locus of control for all healthcare services; whereas, in the United States the private sector provides approximately two- thirds of the healthcare coverage with the federal government functions as provider for the remaining unmet one-third (military health, veteran’s health, and the Indian Health Service), payer (Medicare and Medicaid), and clinical support (CDC, NIH, AHRQ, and many more programs). This chapter will discuss the role of government programs under the headings of provider, payer, and a gray zone and seek to provide aspirational healthcare leaders with an overview of how and when they will interact with federal and state government health programs.

Provider

As of 2021, The United States federal government provides health services for individuals enrolled in the Indian Health Services, Military Health Services, and Veterans Affairs Services. These services are generally provided through a comprehensive integrated health system administered by the Department of Health and Human Services (Indian Health Services), Department of Defense (Military Health Services), and Department of Veterans Affairs (U.S. military veterans). All of these services provide complete medical, surgical, dental, vision, hearing, and mental health inpatient and outpatient services in facilities owned by the sponsoring agency through healthcare professionals employed by the same sponsoring agency. Even though these services are comprehensive, individuals covered under these services may be treated in the private sector as well when geographic or treatment barriers exist.

The Indian Health Service (IHS) provides health services to American Indians and Alaskan Natives and is a byproduct of the tribal governments to federal government relationships reaching back to the U.S. Constitution Article I, Section 8. The relationships between the tribal and federal governments are complex, and, while constitutional, are also contractual and moral agreements with tribal governments due to land displacement through the early years of our country. Comprehensive and integrated IHS health care services are provided through the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with the HHS acting as the owner of all facilities and employer of all personnel.

The military provides healthcare services wherever military personnel are deployed and is considered a moral obligation of society to care for the healthcare needs of those protecting and defending our country. These services can vary from medic provided care in the field to complex medical or surgical care in state-of-the-art hospitals. It is unlikely that civilian healthcare professionals will interact with individuals in the military health system unless there is the need for an extremely rare medical or surgical intervention that cannot be provided within the system. Tricare is an option of the military health system that provides healthcare services around the world for uniformed service members, retirees, and service family members through a system that is very similar to the options available in the private insurance market.

The Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (VAHS) is a national system of clinics and hospitals that provides healthcare services for military veterans. The VAHS is administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs and as with the military health system is considered a moral obligation for the nation to provide for those who have served to protect and defend our country. As with the IHS and military healthcare systems, the VAHS is an integrated, comprehensive healthcare system that prefers to have its members receive services from VAHS facilities and providers although treatment may be authorized in more convenient private settings in recognition of patient geographic barriers or specialized treatment needs.

The final area of government provision of healthcare services is the prison healthcare system. Federal, state, and local governments have an obligation to care for the healthcare needs of inmates and do so through infirmaries, clinics, and hospitals provided by departments of correction and, depending upon the severity of the healthcare condition and prison resources available, may authorize treatment through private facilities and providers. Inmates cared for in private settings are always accompanied by a guard to ensure safety to the private facilities and providers delivering care.

Payer

The federal government pays for healthcare services through three programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Medicare and Medicaid were enacted in 1965 as a part of President Johnson’s Great Society ensemble of programs. Medicare provides healthcare coverage for individuals 65 years age or older, disabled, or who have end stage renal disease. Medicaid is a joint federal and state program designed to provide health care coverage for individuals and families whose incomes are less than 133% of the federal poverty level. CHIP was enacted in 1997 as a part of President Clinton’s healthcare reform efforts. Children covered under CHIP are from families who are not able to afford either employer sponsored or individual private insurance policies and earn too much to qualify for Medicaid. Household income eligibility for CHIP varies by state and ranges from 133% to 400% of the federal poverty level.

All of these programs were enacted into law as amendments to the Social Security Act of 1935: Title XVIII Health Insurance for the Aged and Disabled (Medicare), Title XIX Grants to States for Medical Assistance Programs (Medicaid), and Title XXI State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The Social Security Act of 1935 was enacted by the federal government as a response to the Great Depression of 1935 and as a part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s ensemble of New Deal programs. Originally, Social Security legislation included a national health insurance program that was pulled from the program due to vigorous physician opposition. The final Social Security package included: Old Aged Assistance, Aid to the Blind, Aid to the Disabled, and Aid to Dependent Children.

Medicare

Medicare currently has 4 parts (A, B, C, and D) and has undergone over 265 legislative changes since its inception in 1965. In its current form Medicare is an example of national health insurance (Parts A, B, and D) and statutory health insurance (Part C). Since its inception in 1965, Medicare has grown considerably in enrollees, from 19 million in 1966 (10.5% of the population) to 63.8 million in 2021 (19.4% of the population). From an expenditure lens, in 1966 total healthcare spending was 5% of GDP with Medicare representing 4% of total healthcare spending. In contrast, total healthcare expenditures in 2021 were 19.7% of GDP with Medicare representing 21% of total healthcare spending. Needless to say, healthcare leaders need to understand any single payment source that consists of 21% of all payments.

Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance for the Aged and Blind) is the inpatient hospital part of Medicare that all enrollees receive at no cost. This part of Medicare pays half of all inpatient hospital costs at Medicare set prices that are generally 60% of hospital charges with enrollees responsible for the remaining half. Medicare Part A also covers 72 days of post-hospital skilled nursing care, hospice, and home health care services. Originally, Medicare Part A paid claims on a cost-based payment method, however, due to rapid cost increases, cost- based payments were replaced with the prospective payment system better known as DRGs (diagnostic related groups). DRGs were an attempt to add more structure and predictability to payment for services through the bundling and coding of payments based on disease, severity, and co-morbidities. Despite the intent to control increasing costs, DRGs proved to be an ineffective tool to achieve this goal–probably due to being another form of fee-for-service that awards volume over outcomes. Recently, CMS (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services) has moved to a value-based payment model that focuses on payment by outcome as opposed to activity. At this writing, it is too early to draw definitive conclusions about value-based payments although reports of its effectiveness are promising.

Medicare Part B (Supplemental Medical Insurance Benefits for the Aged and Blind) provides outpatient payment (initially physician office payment), is an optional service, and includes a monthly premium that is deducted from an enrollee’s monthly Social Security check. As the venue for healthcare services has shifted, Medicare Part B has expanded its scope to cover a broad array of outpatient services. In general, these services continue to be paid on a fee-for-service method; however, payment for physician services have evolved through several legislative iterations. The current payment iteration is MACRA (Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015) that simplified payment to a merit-based incentive payment (MIPS) option that consolidated a number of quality payment requirements or a risk-based option offering large payment rewards for positive patient outcomes.

Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) is a private market managed care option available to Medicare enrollees that at minimum includes Parts A and B coverage and frequently covers additional services such as prescription drug coverage (Part D). Medicare Advantage was originally signed into law by President Clinton in 1997 as Medicare+Choice. The program changed to Medicare Advantage in 2003 under President Bush as part of his Medicare Modernization act. The structure of this plan calls for CMS to pay Medicare Advantage providers a set amount every year to provide care at least equivalent to the level of care provided for under Parts A and B of traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage has been a very popular plan that has grown steadily since its inception. As of 2021, Medicare Advantage enrolls 42% of Medicare enrollees and consumes 46% of Medicare expenditures (Freed, Fulesten, Damico, & Nueman, 2021). Healthcare providers typically treat Medicare Advantage just like any other private insurance plan.

Medicare Part D (prescription drug coverage) is the newest entrant into the Medicare ensemble of products. Prescription drug coverage is a major financial burden for individuals in the 65 plus years age group that was not covered under traditional Medicare. When one considers that Medicare was modeled after a 1960 Blue Cross / Blue Shield medical plan that did not include prescription drug coverage, the need to update Medicare to include prescription drug coverage common in medical insurance in the 2000s is understandable. Regardless, this was a very difficult revision for President Bush to negotiate and resulted in a rather complex plan under which enrollees were covered, then not covered, then were covered by catastrophic coverage, on a yearly basis. The complexity of this coverage was addressed in the Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA) that closed the donut hole (period of noncoverage). Like Medicare Part B, Part D is an optional plan Medicare recipients must opt into and pay additional fees. Healthcare providers should ask traditional Medicare recipients if they have Part D coverage when they are including prescriptions in any treatment plan or when they are dispensing prescribed substances or services.

Healthcare leaders should monitor the solvency of Medicare, especially as the aged population increases, and future policy proposals as they are brought up as part of the legislative agenda setting process. Current healthcare issues that will likely be addressed through expansion of Medicare with the creation of additional parts to include payment for long-term care, dental, vision, and hearing. Payment for long-term care was addressed through legislation in 1988 and 2010 with both actions later rescinded by Congress due to the unsustainability of the legislation as written. However, the current process for aged individuals to pay for long-term care is to dissolve their assets and qualify for Medicare. Over the past 30 years (figure 2) Medicaid LTC expenditures have increased from $15 billion to $130 billion and with the aged population projected to increase over the next couple of decades, these cost increases are unsustainable. Similar statements can be made for dental, vision, and hearing needs of the aged population. The prudent healthcare provider should keep an eye on these expenditures and legislative solutions and, in the appropriate time, seek to influence their outcomes.

Medicaid

Medicaid is a program that was developed as a part of President Johnson’s Great Society programs and was modeled after the Kerr-Mills bill (1960) that adopted a federal/state funding model to provide medical care for the impoverished elderly. Formally, Medicaid is Title XIX Grants to States for Medical Assistance Programs (Medicaid) of the Social Security Act of 1935 and was signed into law by President Johnson in 1966. Originally, to be eligible for Medicaid an individual had to be poor and a child, pregnant, female, senior, blind, or disabled. In 1997, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program or Title XXI State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was signed into law by President Clinton. CHIP is a program designed to provide coverage for children from families who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but are unable to afford private health insurance coverage with the range varying by state (133% to 400% of the federal poverty level). While CHIP is not a Medicaid program, it is treated as Medicaid for higher income children and is always linked with Medicaid in the literature and payment model descriptions. The final major change to Medicaid occurred in 2010 through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) which provided for an expansion of Medicaid to anyone under 133% of the federal poverty level or who met the Modified Adjusted Gross Income criteria. The Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) is calculated by taking the adjusted gross income and adding untaxed foreign income, untaxed Social Security benefits, and tax-exempt interest. MAGI is the same criteria used for MarketPlace Insurance subsidies provided in through the PPACA and is limited to enrollees who are 65 years of age or older, disabled, or blind.

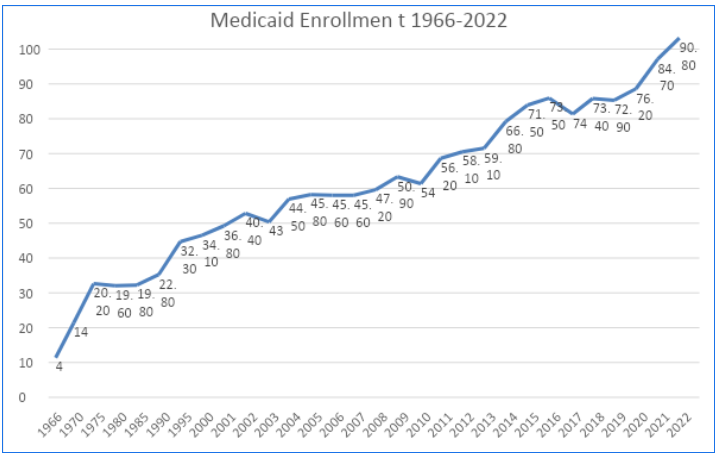

Medicaid enrollment has grown as states have adopted the program and as program revisions have been written into law. In 1966, Medicaid’s first year 4 million enrollees (figure 1) were enrolled which grew to 20 million by 1982 after all states had adopted the program. Medicaid’s next jump to 33 million occurred following the passage of CHIP legislation in the mid-1990s. Enrollment in Medicaid continued to grow throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, frequently aligned with economic downturns, with the next big jump in enrollment following passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 that provided for expanded Medicaid.

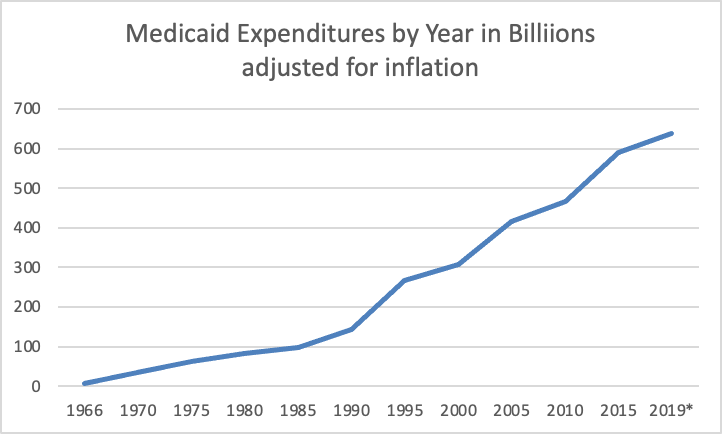

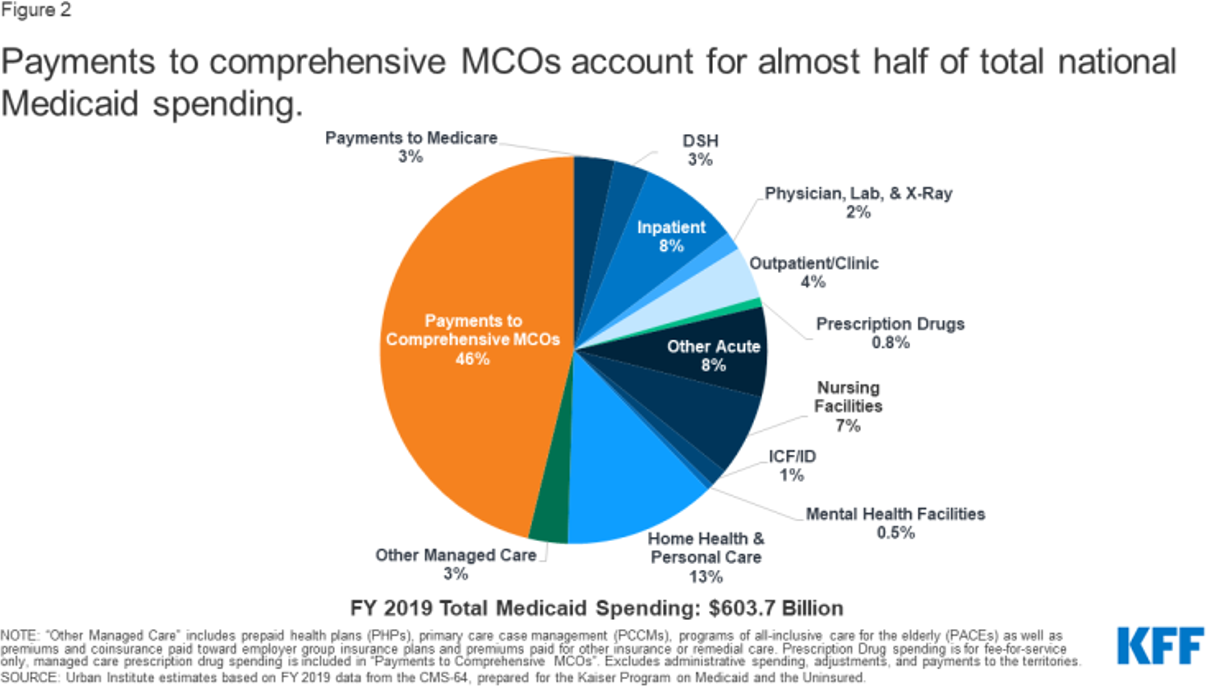

Expenditures are generally correlated with growth (table1) and the additional understanding that the overall cost of care per individual has increased due to advances in medical treatment and technology. Adjusted for inflation, expenditures have grown from $7.12 billion in 1966 (figure 2) to $267.12 billion in 1995 correlating with the implementation of CHIP. Growth of expenditures continued throughout the late 1990s to $591.4 billion in 2015 correlating with Medicaid expansion and finally to $639.4 billion in 2019. While the majority of Medicaid expenditures are directed to Managed Care Organizations (implemented throughout the 1990s – figure 3) 57% of funds are spent on those who are aged greater than 65 years or disabled who only make up 31% of enrollees. From a governmental lens, Medicaid accounts for 7% of federal and 16% of state outlays. To further contextualize Medicaid’s financial burden to states, Medicaid coupled with elementary and secondary education account for 56% of state budgets. Throughout the states, Medicaid funding per enrollee varies widely from $4,900 per enrollee to $12,500 per enrollee with the per enrollee expenditures dependent upon the richness of the elective services offered through Medicaid and coverage of Medicaid expansion enrollees.

From a healthcare administrator lens, it is always to the benefit of healthcare organizations to advocate for coverage of more elective services and expansion of Medicaid. Despite this, Medicaid is known for its traditionally low payment of approximately 40% of charges which is a disincentive to many providers and frequently does not cover the costs of providing care. The federal and state governments consider the low payment an act of community benefit and service. An attitude that varies among providers with those with a more missional and charitable orientation aligning with the benefit and service argument and those with a more profit orientation disagreeing and limiting their services.

Figure 1

Total Medicaid enrollment from 1966 to 2022

Figure 2

Medicaid Expenditures by Year in Billions adjusted for Inflation

Figure 3

Payments to Comprehensive MCOs

The Gray Zone: Supporting Agencies and Programs

Healthcare administrators must be familiar with the collection of federal agencies and programs addressing access and supply. These programs originate at the federal level but the day-to-day coordination of these programs is managed at the state level – with some level of additional state funds added in. Because these programs are coordinated at the state level, healthcare administrators have more influence and involvement in the decision making of this coordination. This mix of programs was created to address unmet healthcare service needs of uninsured adults under the age of 65. Although this group has changed in both numbers and composition over time, it is still a substantial minority of the population at 27.5 million as of 2022.

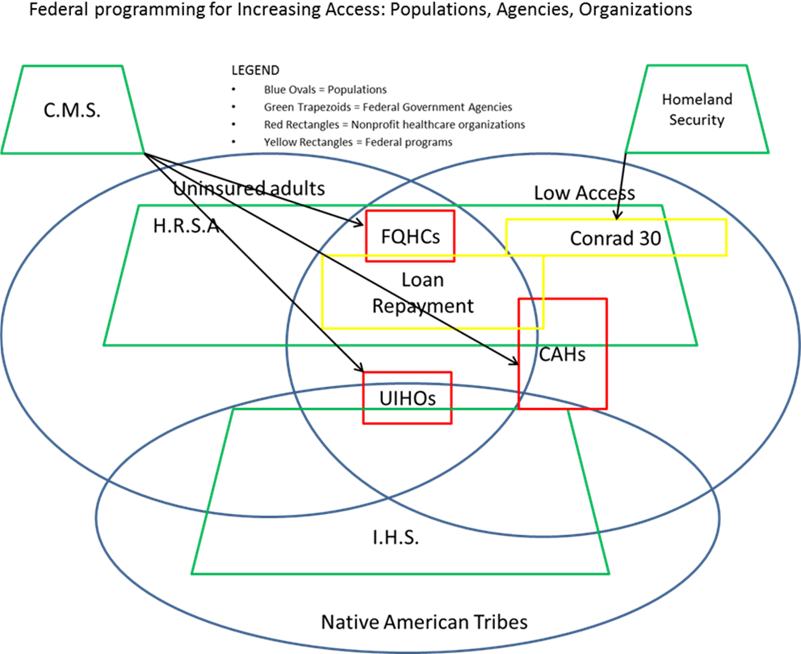

While we most often think of limits to health care access in terms of rural areas, access is also constrained in urban areas. Federal policy addresses geographically constrained access through three separate, but linked, policy measures. First, an application is made for a geographic area to be designated a shortage area for healthcare professionals and/or a population that is underserved. These two geographically defined shortage areas are Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs) and Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). Applications for these designations are submitted by private sector healthcare organizations in concert with approval and support of the state Medicaid agency. After the area designation is awarded the area then qualifies for funding to improve access with federally qualified health centers (FQHC), which may include health care facilities for urbanized Native Americans funded by the Indian Health Service and entitled Urban Indian Health Organizations (UIHOs). These designations also enable funding to improve supply via the State Loan Repayment Program (SLRP) and Conrad 30. The latter two encourage providers (either US citizens or foreign medical graduates [FMGs]) to practice in areas with low access. A large proportion of this activity originates inside of the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA), with some involvement from Homeland Security, the Indian Health Service and CMS (figure 4).

Figure 4

Federal Programming for Increasing Access

The access organizations, FQHCs and UIHOs, are federally funded healthcare facilities that provide primary health care services and often optical and dental and less frequently rehabilitative services. Those served must be uninsured adults, although since the early 1990s this has been broadened to include Medicaid and Medicare adult enrollees. As the approval for these organizations requires buy-in from each state’s Medicaid agency, healthcare administrators that are appointed to represent private healthcare organizations within a state may influence these organizations.

The two programs affecting the supply of providers in underserved areas, SLRP and Conrad 30, are also administered at the state level. The annual choices for the number and types of providers to be emphasized are determined at the state level by a state appointed committee, generally residing within the state’s Medicaid agency. In the case of SLRP it is a decision on how much of an applicant’s student loans to repay (annually) for what desired provider types. This is further affected at the state level by the amount of state-funding each state decides to add to this program. In the case of Conrad 30 it is the types of providers to be selected each year as well as any changes to recruitment processes and incentives desired to fill each year’s slate of healthcare professional openings. Each state and territory may use this program to bring in 30 FMGs each year. It is almost unheard of for any state or territory to recruit less than 30 in any given year. The Bureau of Health Workforce within HRSA also supports the supply end with a variety of programming for graduate medical education and graduate nursing education.

Following the theme of healthcare delivery, four federal agencies are responsible for the funding of innovations in health service delivery. The AHRQ, CDC, SAMHSA and HRSA. The focus of these innovations are within each agency name. For the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) the focus is on improving quality, for the CDC it is the broad swath of public health programming, for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) it is mental health and substance abuse, and for HRSA it is focused on resources and services for the underserved. These activities are primarily performed through competitive grant making, although AHRQ also uses competitive government contract mechanisms.

The funding of basic clinical, translational, and health services research is conducted by several federal agencies, some previously named as responsible for previously discussed programming. The best-known federal agency engaged in this is the National Institutes of Health which funds basic clinical research across a broad variety of areas with a budget of $41.7 billion (NIH, 2022). Similar to the funding of delivery innovations, a number of agencies also fund research in these three areas – always focused on each agency’s specialization. So, AHRQ funds translational research with a focus on quality, the CDC with a focus broadly on the same for public health, SAMHSA for mental health and substance abuse, and HRSA for resources and services to the underserved. Added to this activity is the National Academy of Medicine, formerly known as the Institute of Medicine. This organization focuses on larger picture issues within the same zone, perhaps best exemplified by the groundbreaking IOM publication, To Err is Human, which first defined and characterized the extent of medical errors that take place annually in the United States (Kohn, Corrigan, Donaldson, 1999).

Lastly, we have the federal funding of ancillary public health activities. This includes programming that is within the field of public health but administered by agencies other than the CDC. Three areas are important to understand, worker’s compensation, inside the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), nutrition programming administered by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the disposal of medical waste overseen by the Environmental Protection Agency. A component of OSHA’s responsibility for workforce safety includes a mandate for paying the claims for injuries sustained by individuals while employed. From the overall federal, state, and employer fund, in 2019 the medical claims paid totaled $31.3 billion – not an insignificant amount!

Improving nutrition for low-income families – a clear concern of public health experts – is administered by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), primarily through three programs, WIC (Women, Infants and Children), SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), and the Free and Reduced School Lunch Program and Summer Feeding Program. These three programs all provide access to free or reduced cost access to food items (WIC and SNAP) or meals for low-income children via the School Lunch and Summer Feeding programs.

Additional Congressional and Executive Agencies

Five additional federal agencies (states and local government have similar agencies) healthcare administrators should know about are the Congressional Budget Office (1974), Joint Committee on Taxation (1926), Congressional Research Service (1914), General Accounting Office (1921), and the Office of Management and Budget (1921). These agencies provide Congress and the Executive branch support in the development of legislation and subsequent implementation and evaluation of legislation. Their relevance to healthcare administrators is their reflection of how Congress and the Executive branches view governmental actions and programs and what administrators, and their organizations are or may be held accountable to in the future if they agree to participate in governmental sponsored programs.

Key Words

Federally qualified health centers: Primary care centers that receive higher reimbursement from federal programs due to serving a majority of uninsured and underinsured patients (including Medicaid enrollees).

Medicaid: The joint federal and state program that pays for healthcare services provided to children and families with household incomes under the poverty level.

Medicare: The federal program designed to pay for medicare care for retirees (those aged 65 and older), the disabled, the blind, and those with end-stage renal failure.

TriCare: The federal program that provides access to medical services for retirees of the armed services.

UrbanIndianHealthOrganizations: Primarycare organizations funded through the Indian Health Service to provide medical services to tribal members living in cities, away from reservation services.

References

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020). National Healthcare Expenditures.

Cha, A. E., Cohen, R. A. (2022). Demographic Variation in Health Insurance Coverage: United States. HHS: National Health Statistics Report Number 169 retrieved at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr169.pdf.

Freed, M, Fulesten, J., Damico, A., & Nueman, T. (2021). Medicare Advantage in 2021: Enrollment Update and Key Trends, Kaiser Family Foundation retrieved at: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage- in-2021-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

Kohn K.T., Corrigan J.M., Donaldson M.S., eds. (1999) Washington, DC: Committee on Quality Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine: National Academy Press.

NIH, Budget. (2022) retrieved at: https://www.nih.gov/about- nih/what-we-do/ budget#:~:text=The%20NIH%20invests%20about%20%2441.7,res earch%20for%20the%20American%20people.