5

5 – Population Health Management

Anne M. Hewitt, PhD, MA

Seton Hall University

“Quality health care gives people the peace of mind they need to participate fully in their communities, spend time with those they love, and pursue their part of the American Dream.”

– U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra

Learning Objectives

- Describe the importance and role of population health management

- Explain health promotion/wellness as a major population health management strategy

- Discuss Social Determinants of Health’s impact on Population Health Management’s approach to care

- Apply Population Health Management risk concepts for vulnerable populations

- Identify major Population Health Management strategies to improve health outcomes

- Provide examples of new Population Health Management innovations

Introduction

Many of today’s college students will be familiar with the well- known World Health Organization’s definition of health as the “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1946). But they are much less likely to recognize two other major health terms – population health (PopH) and population health management (PHM). This situation is understandable given the low public awareness of these health approaches and the complexity of their concepts and strategies. First, we need to understand that Populations refer to not just individuals, but the context in which people live, work, and play in local communities (Carlson, 2020). Next, we see the population concept linked with health, and the term population health is described as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group” (Kindig & Stoddart, 2003). Population health (PopH) is extremely broad and includes guiding principles from social, physical, and biological environments, lifestyle behaviors, and health policy domains (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2013). Focusing on populations’ health versus targeting individual health has become an essential framework for delivering health care.

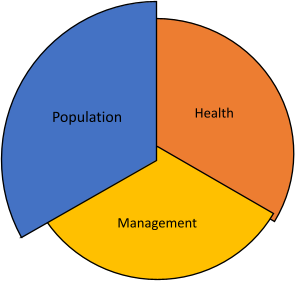

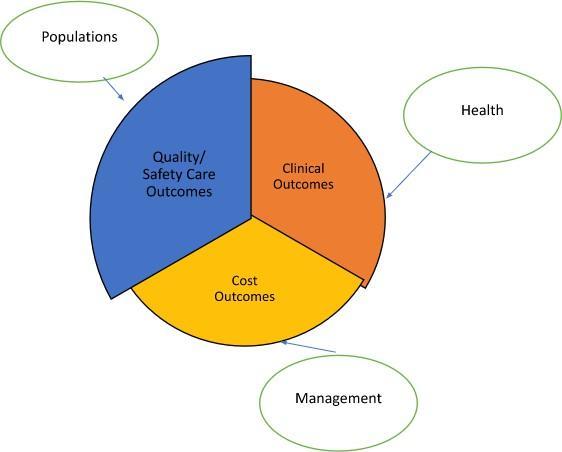

The American Hospital Association, a major health sector stakeholder, defines Population Health Management (PHM) by adding and integrating a strong management component. “PHM is the process of improving clinical health outcomes of a defined group of individuals through improved care coordination and patient engagement supported by appropriate financial and care models” (AHA, n.d.) Together, these definitions explain the new PHM pathway that transitioned from a disease-only treatment model for individuals to a population health strategy that focused on groups, and finally to a management model that requires clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and safer health outcomes for all. Figure

1. The PHM Framework shows all three components as an integrated system that distinguishes it from previous models.

As a 21st-century model of healthcare, PHM has already impacted how American populations receive healthcare today and will in the future (Jha, 2019). Five of the most important PHM goals and strategies will be described and discussed throughout this chapter:

- Improving health outcomes for all populations

- Focusing on selected groups, not single individuals

- Prioritizing health equity to eliminate disparities

- Emphasizing quality to improve care coordination

- Ensuring that the patients are involved and engaged

- Managing the relationship between cost and improved outcomes.

Figure 1

Population Health Management Framework

Discovering Population Health Management: Improving Health Outcomes Catalysts for Change

The United States health sector is one of the largest industries in the country, and its size, diversity, and complexity have combined over the years to create an unsustainable healthcare delivery structure. Today, our healthcare sector is struggling to meet the demands of all Americans (The Commonwealth Fund, 2016). While it is easy to suggest that the recent COVID-19 pandemic is the major reason for overwhelmed hospitals, burned-out healthcare providers, and a public grappling to understand the high cost of healthcare, the underlying systemic issues became apparent much earlier. Beginning in the 1990s and continuing into the new century, a consensus was building that the U.S. healthcare system was fragmented, inefficient, and with too many quality and safety concerns. (Jha, 2019). Health costs have now reached 19.2% of the Gross Domestic Product (CMS, 2021). From 1970 to 2000 the total national health expenditures increased from $353 to $1,366 billion and have now escalated to 3,800 billion dollars (Kamal, McDermott, Ramirez, & Cox, 2020). Industry leaders from the American Hospital Association and other influential groups issued calls for change (IHI, n.d.; Saha, 2017; NPP, 2008) supported by health policy experts who suggested a need for new models of care (Nash, 2012). The government introduced important health legislation to update the health care system by encouraging technology improvements such as the adoption of Electronic Health Records (CDC, 2018), and prioritizing patient concerns in the areas of quality care outcomes, cost transparency, medical information protection, and security (HIPPA Journal, 2020). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) (PPACA, 2010), more than any other influential factor, provided the momentum and opportunity for needed health infrastructure transformation (Goldstein, Shephard & Duda, 2016).

The PPACA Mandate: Community Health Needs Assessment

The PPACA recognized that community healthscapes impact the health status and quality of life outcomes of every population-of-interest. Although many clinical measures of health status were available, diverse health needs existed at the community level that were not addressed by local hospitals. The PPACA requires each hospital, every three years, to determine their community’s needs by conducting a Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNA) in partnership with other stakeholder community agencies, such as the local health departments. The goal is to assess the entire community’s population health status and develop a collaborative community strategic plan, a Community Health Improvement Plan (CHIP), to implement action items that target the unmet needs. (IRS, 2020). The CHNA, which resides within IRS jurisdiction, also establishes protocols detailing a hospital’s financial assistance and emergency medical policy, limitations of charges and billing, and collection procedures. The IRS also determines the eligibility of a hospital or health system’s claim of non-profit status. Completion of a CHNA is a complex and detailed process, involves many hours of data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and begins usually more than a year in advance. The PPACA stipulates a financial penalty tax of $50,000 per hospital for non-compliance and the IRS can revoke a hospital’s tax-exempt status (IRS, 2020).

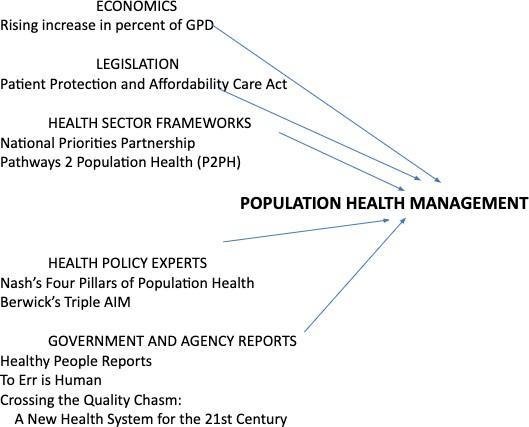

The PPACA, over 1200 pages, also offered a flexible framework for many important PHM innovations in addition to the CHNA, including the Accountable Care Organization model, the expansion of Medicaid to underserved populations, and the linkage between healthcare delivery of services reimbursement and health population outcomes. See Figure 2 for a summary description of these drivers of healthcare change.

Figure 2

Drivers of Healthcare Change Leading to Population Health Management

Although America’s health sector continues to be challenged, the situation would be more serious without the PHM healthcare system delivery model and its benefits and advantages (Blumenthal, Collins, & Fowler, 2020).

Foundations and Key Components of Population Health Management

In 1979, a landmark document “Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention”, recommended for the first time a coordinated, healthcare national strategy (History of Healthy People, 2021). Continuing over the years, the five editions of Healthy People have regularly provided evidence for setting health goals and objectives to address the enormous variation in the distribution of disease and morbidity for various at-risk and minority populations (ODPHP, 2018).

The latest version of our national public health objectives, Healthy People 2030, lists 355 core objectives ranging from reduction of chronic diseases to mitigation of the contagious disease that reached a pandemic stage, COVID-19. This expansive document not only provides evidence-supported objectives, but also identifies metrics to help track them. The HP 2030 goals serve as guidelines for all collaborative health efforts, including PHM.

- Attain healthy, thriving lives and well-being free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death.

- Eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all.

- Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and well-being for all.

- Promote healthy development, healthy behaviors, and well-being across all life stages.

- Engage leadership, key constituents, and the public across multiple sectors to act and design policies that improve the health and well-being of all (CDC, 2020).

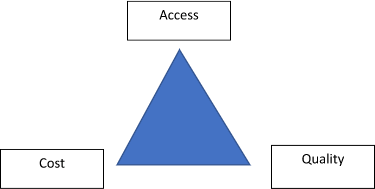

Health policy experts also responded to the challenge of improving health and produced several major national health commentaries to guide new models. Two prominent reports that attracted enormous attention and concern were the Institute of Medicine’s, To Err is Human (NAM, 2000) and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (NAM, 2001). All Americans should expect safe, quality care which is free from mistakes, accessible, and effective. Both documents describe crises within the health sector needing drastic and immediate change. However, it was a seminal article that introduced one of the most important PHM components – Triple Aim. The Triple Aim concept was a proposed solution to the conundrum of unmet health needs by focusing on three key aims of health care delivery: access, quality, and cost (Berwick, Nolan, & Whittington, 2008). See Figure 3.

Figure 3

The Original Triple Aim

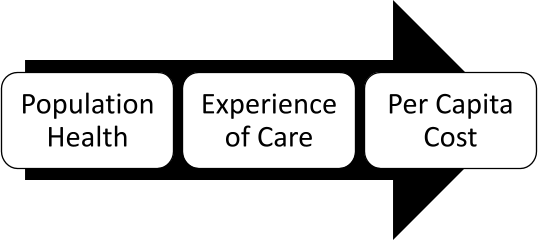

The Institute for Health Improvement (IHI) built on the three major health goals by transforming the model into actionable strategies that would play a crucial role in improving health care outcomes. Figure 4 depicts a schematic of the IHI’s iron triangle.

Figure 4

IHI Iron Triangle

The Triple Aim framework supplied the integration perspective and the ACA legislation supported infrastructure flexibility, but a broader policy perspective involving other sectors outside of healthcare was missing. The Health in all Policies (HiAP), developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is a collaborative health decision-making process for all community sectors and policy issues (CDC, 2016). HiAP is a blueprint for health strategies that include municipalities, communities, industry, and the health sector to improve health outcomes for all (APHA, 2020). Based on the inclusive perspective of Triple Aim, HiAP aligned all the health stakeholders to ensure cross-sector engagement and comprehensive support. Figure 5 shows the HIAP framework and process.

HEALTH IN ALL POLICIES RESEARCH CENTER INTRODUCTORY VIDEO (CDC)

Figure 5

Health in all Policies Circle

Health in all Policies: An Example

The Health in all Policies framework appeals to all types of states and localities regardless of size or location. For example, Vermont developed a complete multi-sector health action plans specific to a rural state (Vermont Dept of Health, 2018). The Vermont action plan, based on the RWJ Foundation’s Culture of Health, includes a Total Health Expenditure Analysis, an accountability analysis that examines Vermont’s health spending across all sectors. Developed by the Vermont Health in All Policies Task Force, a cabinet-level group appointed by the Governor, this document HiAP policy document demonstrates the advantages and benefits of cross-sector collaboration and cooperation.

Vermont Department of Health. (March 30, 2018).Creating cross-sector action and accountability for health in Vermont: Guidance from a rural state.

https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/ADM_CoH_Guide.pdf

The Population Health Management Framework: Why is it Different?

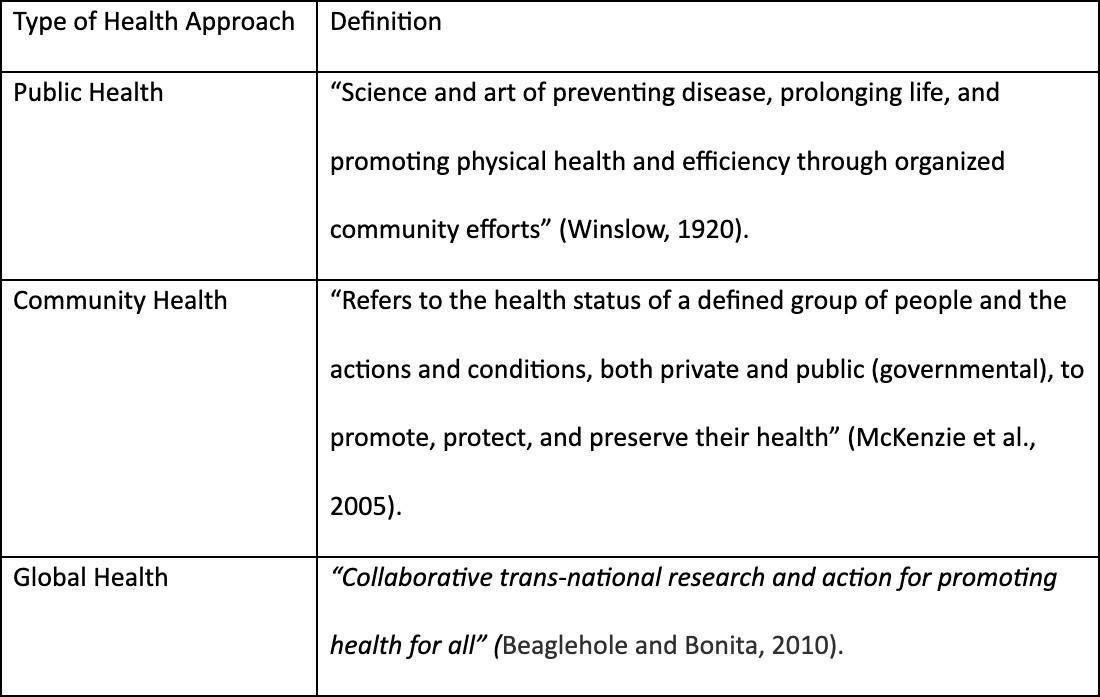

PHM’s health care delivery strategies often overlap with other perspectives as they all seek to improve health care outcomes. Public, community, and global health approaches all address health needs, but with different perspectives and goals. Confusion often exists between public health, population health, and population health management. Table 1 provides three standard definitions of the other health approaches.

Table 1

Definitions for Public, Community, and Global Health

Beaglehole, R., & Bonita, R. (2010). What is global health? Global Health Action, 3, 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142.

McKenzie, J., Pinger, R., Kotecki, J. (2005). An Introduction to Community Health Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 5.

Winslow, E (1920). The untilled fields of public health. Science. 51(1306):23–33.

The PHM framework uniquely combined three separate perspectives, populations, health, and management, into a viable solution for delivering healthcare in the United States. The PHM Outcomes Framework is the key to understanding the differences among the other health approaches. See Figure 6 to view the PHM Outcome Framework.

Figure 6

Population Health Management Outcome Framework

One of PHM’s primary distinctions is a priority focus on specific populations unlike the other types of health care delivery systems. PHM health payors, health providers, and organizations define their priority populations and are not bound by government mandates, local municipalities, or global health perspectives. Even local public health agencies serve those individuals within a defined and designated geographic area. The same is true of community health, but often their geographic areas differ from the public health area of interest. Global universal health focuses on safety-net services for all. Only the PHM strategy allows health entities to independently define their at-risk and priority populations to provide better care – care that is coordinated and specifically designed for a vulnerable group. This tailored care translates into better quality and safer outcomes.

A second innovative characteristic of PHM is the direct relationship of improved outcomes to reimbursement cost. For example, PHM uses risk-based alternative payment systems where health providers and agencies can receive monetary incentives or disincentives depending on the amount of monetary risk assumed for covering their defined population. The other three approaches rely on payment systems from the government, whether federal, state, or municipal, and/or philanthropic funding. PHM organizations’ monetary rewards are now directly tied to a priority group’s health status. This emphasis on value over volume, instead of fee-for-service leads to better cost outcomes (NEJM, 2017).

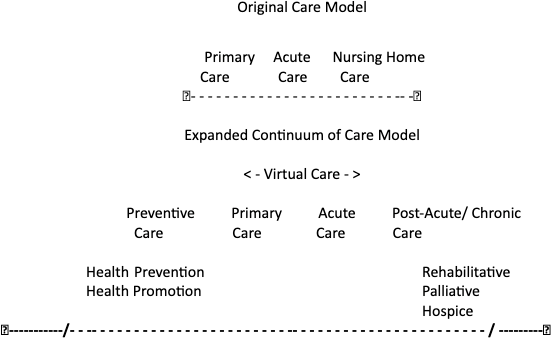

The third distinction is the approach to care as aligned with clinical outcomes. PHM focuses on appropriate care, offered at the right time, in the right place, and by the right type of provider. To make this happen, PHM depends on an expanded Continuum of Care (Surendrank, n.d.), and not just the 20th-century primary, acute, and nursing home care model. See Figure 7 showing an expanded continuum of care.

Figure 7

Comparison between Original and Expanded Continuum of Care Models

The Role of Health Promotion and Wellness: Ensuring Patient Engagement

PHM delivery strategies often overlap with the other health approaches, and the universal alignment of health promotion and disease prevention throughout the PHM model serves as an important example. No longer is hospital or acute care the only approach to ensure positive health outcomes. Now the entire health sector emphasizes preventive care to be proactive and delay the development of chronic diseases that last a lifetime.

Public Health Strategies Applied to Population Health Management Strategies

The World Health Organization’s Ottawa Charter (1986) defines health promotion as the process of enabling people to increase control over their health and its determinants, and thereby improve their health. Health promotion programs and activities are “any type of planned combination of educational, political, environmental, regulatory or organizations mechanisms that support actions and conditions of living conducive to the health of individuals, groups, and communities.” (Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology, 2012).

Disease Prevention includes three major approaches, all inherent in public health’s mission as mandated by the American government.

Primary – Refers to proactive initiatives such as vaccinations, reducing risky behaviors, and banning substances known to be associated with disease, to prevent exposures to negative health effects and outcomes before they occur.

Secondary – Refers to activities such as screenings (cancer and other diseases) to identify at-risk conditions or diseases at the earliest onset of signs or symptoms such as monitoring blood pressure and regular mammography examinations.

Tertiary – Refers to mitigating or slowing or stopping a disease progression using optimum treatment options and encouraging self-management of disease conditions (IWH, 2015).

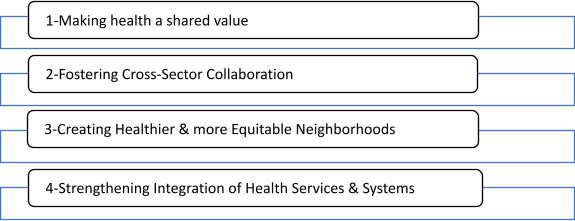

By integrating Health Promotion and Disease Prevention within standard healthcare protocols, PHM continued the shift from the medical model to a population-based approach that encouraged health professionals to move beyond hospital-only provided acute care and actively seek collaborations withinthe community. The Culture of Health initiative, developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Rand Corporation outlined a holistic and ecological health framework (RWJF, 2022). Four action steps describe the process of developing community solutions in a collaborative process and a fifth step outlines the processes for improvement and assessment to ensure sustainability. See figure 8.

Figure 8

The Culture of Health Action Steps.

The Deahl family has just welcomed a new baby into their home. Mom’s obstetrician had previously arranged for bi-weekly mobile check-ins, linked her with pre-natal classes for couples, scheduled visits to ensure a safe and secure home environment, and enrolled her in virtual follow-up support classes. She and her significant other will both receive work release time, and company health coverage ensures easy access to healthcare services. She also received special transportation waivers to make sure she arrives for all baby’s check-ups. On her first trip out with the baby, at the grocery store around the corner, she is delighted to discover a special changing station ready and available. She also receives weekly baby check-in reminders for new Moms and can request a face-to-face chat with the pediatrician’s office if necessary. On a nice day, she takes the baby for a quick walk to the local park and is amazed to find sidewalks designed for easy access, special bike lanes for safety, paths for senior walking and state-of-the art running tracks available.

Population Health Management’s Focus on Patient Engagement

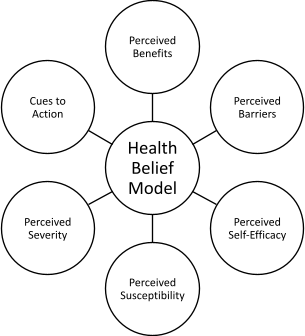

Expanding the community and health care options addresses some unmet vulnerable population needs, but improved health outcomes require patient involvement and engagement. PHM is most concerned with understanding individuals suffering from chronic conditions (Bernell & Howard, 2016). Three of the top five chronic conditions associated with mortality in the United States are diseases that are linked to negative health behaviors: heart disease with lack of exercise, Type 2 diabetes with obesity, and certain cancers with cigarette smoking (Ahmad & Anderson, 2021). Health behavior models for helping individuals modify and change unhealthy behaviors are often part of PHM action strategies for at-risk chronic disease populations. Two of the most notable and successful include the Health Belief Model (HBM) (Champion & Skinner, 2008), a framework for understanding individuals and their motivations for change, and the Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model (TTM) (LaMorte, 2019) that supports diverse at- risk populations who may be struggling with addictive health behaviors.

Figure 9

Health Belief Model

The Health Belief Model focuses on the person’s perceptions of a disease or a condition. Imagine an individual struggling with extreme overeating. How would you help them improve their health decisions and alter daily activities? Do they see the benefits of cutting down on the amount and types of food they eat? Do they feel they can make a change? Do they think the trade-offs will be worth the effort or that having diabetes is not a life-threatening disease? The HBM helps the health provider and patient connect using cues to action to improve those important health decisions from better outcomes.

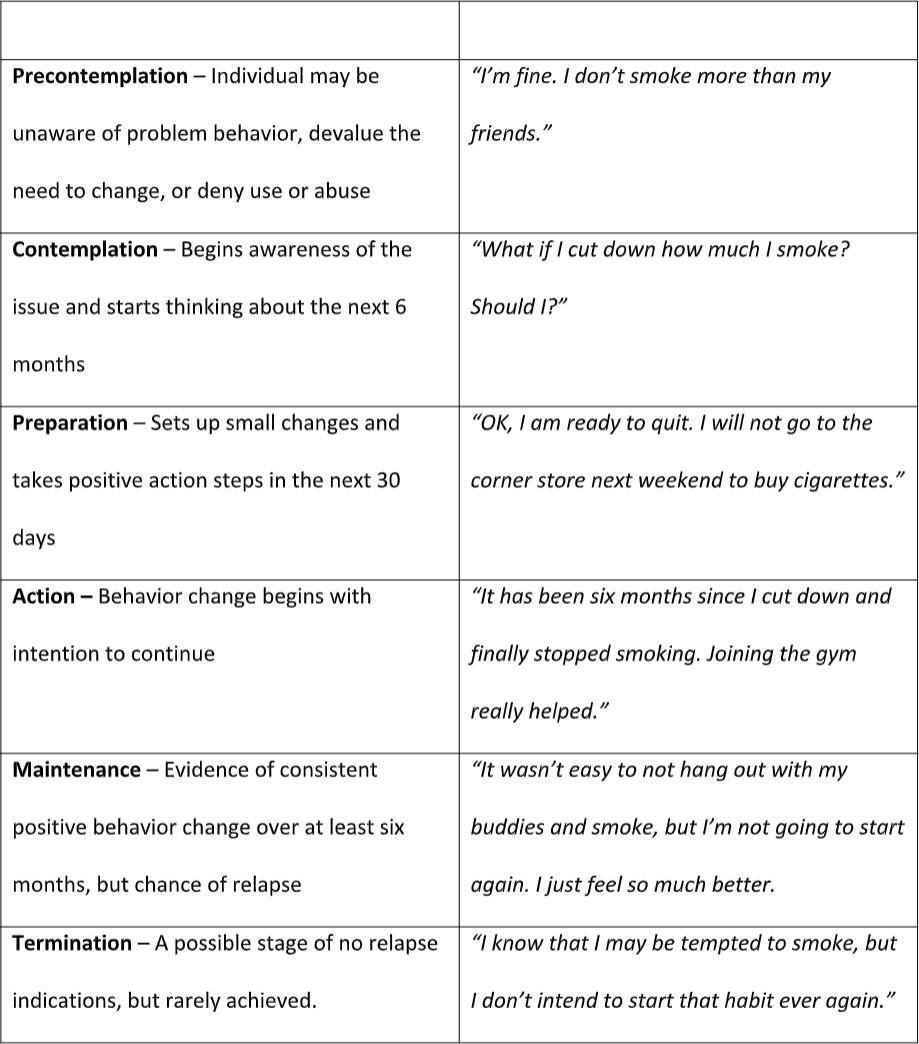

Another behavior change framework is the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) based on six phases of a change cycle – (Precontemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, Maintenance, and Termination) (Prochaska, 2008). The TTM framework allows individuals to move fluidly through the model, but also recognizes that some people encounter barriers and disappointments and move backward to a previous phase. Review the TTM application example in Table 2.

Table 2

Applicational of the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (Stages of Change)

Adapted from Hewitt, A. (2021). Population health models – Part II: Care coordination continuum, behavior change, patient engagement, and telehealth. In A. Hewitt, J. Mascari, & S. Wagner (Eds.), Population health management: Strategies, tools, applications, and outcomes (pp. 155-172). Springer Publishing Company.

PHM succeeds as a healthcare delivery framework due to its integration of health promotion and prevention emphasis and use of the expanded patient-centered health behavior models tailored for specific sub-populations. Health promotion strategies can be health awareness campaigns for flu shots, mobile cancer screenings, and telephonic health coaching for improving lifestyle behavior changes. PHM emphasizes health activities that are patient-centric to ensure successful outcomes for all diverse populations.

Ensuring Health Equity for All Americans: Prioritizing Health Equity

The most pressing healthcare sector issue is the impact of Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) on population health outcomes (Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, 2008). Healthy People 2030 emphasizes the elimination of health disparities and the achievement of health equity as a primary goal (CDC, 2020). Eliminating bias and discrimination remains a primary imperative for all health professionals as they seek to provide inclusive programs, opportunities, and interventions for better health status (APHA, n.d.).

Diversity is an appreciation and respect for differences and similarities (Dicent Taillepierre, 2016) and requires respecting consumers, patients and coworkers’ perspectives, and competencies. How do we recognize and appreciate diversity? First, by accepting that everyone is unique with individual differences and then implementing inclusion strategies to show value, respect, and support in all situations for all populations. (HUD, n.d.). Health disparities are preventable differences in the causes and burden of disease, injury, and violence (CC, 2008). Health equity is not the same as health equality. Health equality is ensuring that every individual has an equal opportunity to make the most of their lives and talents (Equality Human Rights Commission 2018). Health equity refers to stronger actions that support the absence of unfair and avoidable remediable differences in health among population groups defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically (WHO, n.d.).

Health disparities continue to challenge the healthcare delivery system as a 2021 study recently confirmed that Black, Latino, and Asian groups were disproportionately more likely to receive a positive diagnosis and to be admitted to intensive care units for COVID-19 than other populations (Magesh et al., 2021, Ray, 2020). PHM strives to tailor health promotion and care strategies specific to vulnerable populations such as groups with multiple chronic diseases, sub-populations struggling against substance abuse, or individuals’ poor general outcomes linked to the impact of the social determinants of health (SDOH) (Dicent Taillespierre, et al., 2016; HUD, n.d.)

HEALTH EQUITY VS. EQUALITY (CDC).,

Video Transcript: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/vide…

This video can also be viewed at https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/vide…

Impact of Social Determinants of Health

SDOH refers to a group of major factors that have both direct and indirect impacts on the health status of any population. Experts define SDOH as “the places where people live, learn, work and play (US DHHS, n.d.). Table 3 outlines the five major categories of SDOH and provides specific examples (Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014).

Table 3

The Five Major Categories of Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Categories

Adapted from Braveman & Gottlieb, (2014). The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):19-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S206

Today, we know that SDOH directly determines 80% of individual health outcomes (Manatt Health; Phelps & Phillips, LLC, 2019) compared to only 10% attributed to healthcare. What difference does it make if you live two blocks from the best hospital in the country if you cannot afford health insurance or your family has food insecurity and is not sure if they have enough money for the next meal? Individuals impacted by SDOH over a lifetime face lower life expectancy rates and higher incidences of chronic disease (Noonan, Velasco-Mondragon, & Wagner 2016). SDOH, known as upstream health factors, are the conditions, situations, and environment that lead to health inequities and disparity. Upstream simply means that they are the causes (Manchanda, 2019: Merck, 2018). Downstream factors refer to costs and burdens of treatment for chronic conditions, relapsing and related complications that could have been prevented by addressing the impact of SDOH.

Leveraging Population Health Data to Manage At-risk Populations: Focusing on Groups

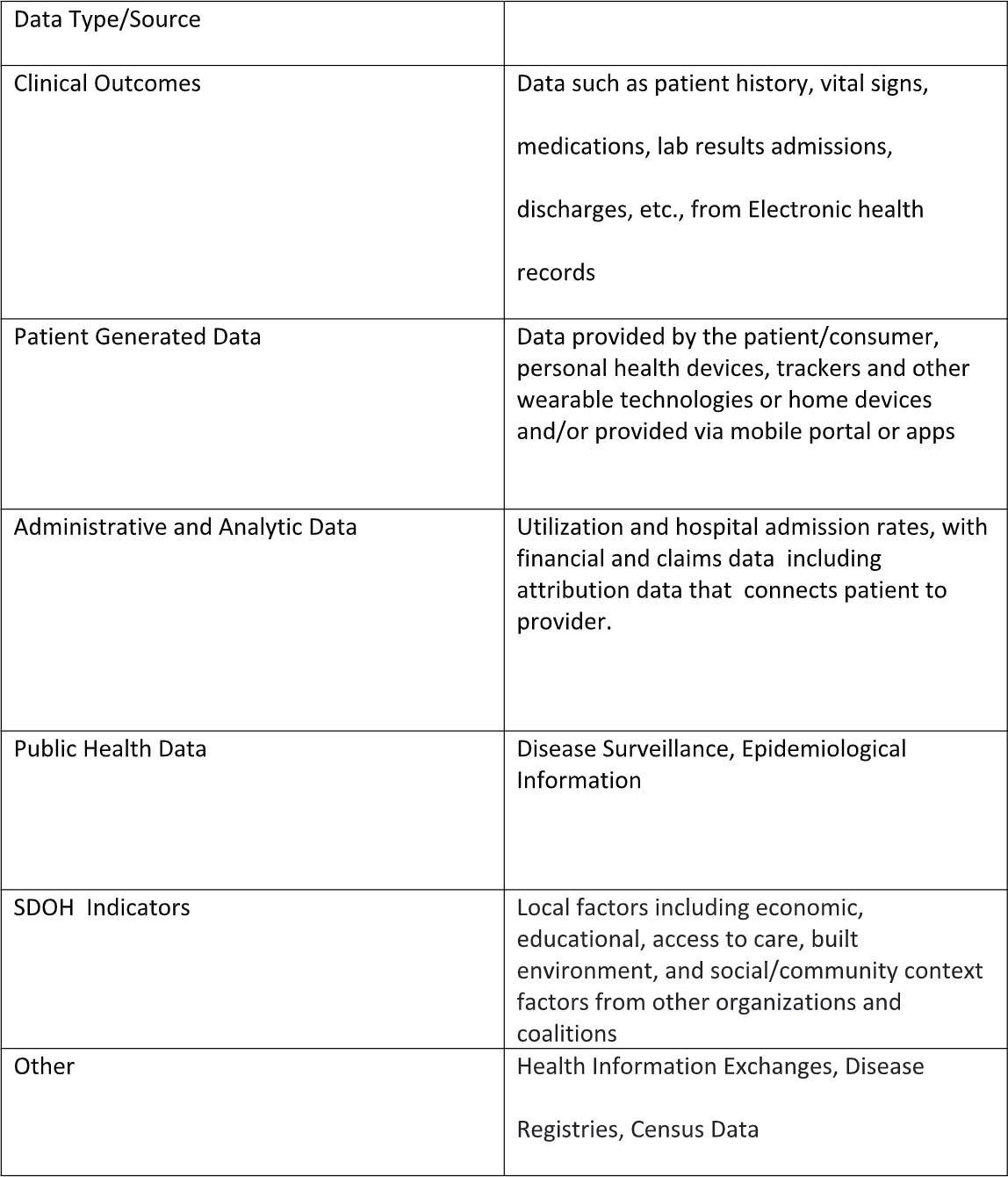

PHM interventions and delivery of care activities cover priority groups and sub-populations at risk for SDOH negative health outcomes. Without appropriate data, these vulnerable populations can be missed or overlooked. Over time, national legislation encouraged the development, integration, and adoption of technology such as electronic health records (EHRs) which are used to obtain important patient data. Data that is timely, valid, and dependable informs decision-making and assists in identifying priority populations with unmet needs.

Health data analytics is a tool that incorporates technologies and processes to measure, manage, and interpret diverse sets of healthcare data (Looker Data Sciences, Inc., 2020). In addition to EHRs, relevant data is available from public health sources, hospitals, primary care providers, ambulatory care, proprietary insurance and companies, pharmacies and the pharmaceutical industry, and other major health payers. Public health data provides detailed information on mortality and morbidity rates of given populations. Managerial epidemiology is simply applying this information to population health decision- making (Fleming, 2013). Even internet search engines collect useful health data such as the Google Flu Trends Estimate which aggregates search query data across regions to identify flu trends (Google Inc., 2014). Table 4 identifies the types of data available when assessing a specific priority population.

Table 4

Healthcare Data for Population Health Management

Johri. N. (2021). Health data analytics for population health management. In A. Hewitt, J. Mascari, & S. Wagner (Eds.), Population health management: Strategies, tools, applications, and outcomes (pp. 79-101). Springer Publishing Company.

Scherpbier, H., Walsh, K., Skoufalos. (2021) Population health data and analytics. in D. Nash, A. Skoufalos, R. Fabius, &

W. Oglesby (Eds.), 3rd ed., Population health: Creating a culture of wellness (pp.114-135). Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Many important and useful data analysis techniques exist and are available to population health managers such as data aggregation, analytics and reporting, and visualization (Johri). Additional advanced techniques include:

- Predictive modeling, which is used for forecasting future needs and costs,

- Artificial intelligence or AI that relies on technologies capable of capturing the complex process of human thought, and

- Machine learning, which uses artificial intelligence to repeatedly learn from large data sets and improve the identification of patterns of health status and outcomes (Johri, 2021).

- The process of data integration and the ability to interface with multiple databases is known as interoperability and is essential for permitting data access and interpretation (Roberts, 2017).

These diverse data tools inform PHM decision-making with information not available even a few years ago.

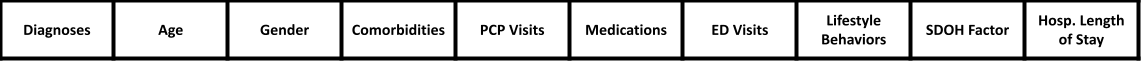

Understanding Different Populations

PHM requires carefully selecting data points from multiple datasets to understand a pattern of illness or treatment condition to determine who is at risk for a poor health outcome. Risk is a probability or a chance that an event or condition may occur. Determining a health risk requires both technical and clinical expertise to carefully select only those characteristics that determine the likelihood of impacting health status. Of course, PHM relies on standard profile metrics that are always relevant, such as age, gender, current health medications, and health status as well as the overall utilization of health care treatments. PHM also seeks to identify groups of vulnerable individuals who may overuse healthcare simply because they do not have a plan for coordinated care. Hotspotting refers to a term that identifies people with multiple co-morbidities who continually overuse the emergency room for health care and whose total health care can approach a million dollars in a single year (McIntire et al., 2021).

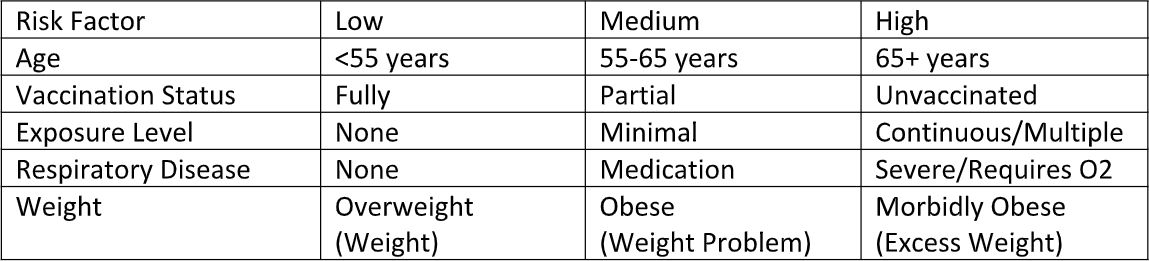

The selection process and analyses of specific risk factors (an exposure that is associated with a disease or condition, without certainty) are combined to develop a risk score (Mascari & Hewitt, 2021). The risk score refers to the likelihood of an event occurring within a short timeframe, six months. This risk score forms the basis for the selection of a sub-population appropriate for health interventions which are referred to as risk segmentation. Table 5 shows a fictitious risk segmentation grid for a generic disease. Note the various risk factors would change based on if the disease or condition were contagious or chronic.

Table 5

Risk Segmentation Factors for Generic Disease

Once the major risk factors are identified, the next step would be to complete a patient risk stratification grid based on the selected risk factors and scores. Since the risk factors are identified, the grid identifies the level of risk for each factor, either low, medium, or high. Table 6 shows a generic example of a Risk Stratification Matrix.

Table 6

Generic Example of a Risk Stratification Matrix

Remember that within each at-risk sub-population there could be thousands of people, which is a primary consideration for population health managers. They must develop the appropriate patient care delivery system and protocols to effectively impact those vulnerable groups while managing costs. Many types of interventions may be needed to produce positive health outcomes, and they can range from single episodes of care such as a vaccine to weekly visits from a designated health practitioner. The level of healthcare strategic intervention is determined using evidence-based decisions on which health provider type such as physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or others, who will deliver the care, how often, and how that care will be delivered whether telephonic, virtual, at home or face-to-face in an office.

Risk Segmentation Decision-Making Example

A population health manager develops a disease intervention plan and protocol for approximately 10,000 enrolled patients. The cost of this proactive intervention is inexpensive at $1.00 per patient per month (PPPM), but research suggests the protocol reduces medication costs by $5.00 PPPM. A total savings of $480,000. If the intervention’s actual cost exceeds more than $5.00 per person, the PH manager will have lost a significant amount, and the intervention is unsustainable. Linking health outcomes linked to cost-effectiveness relies on optimum data and tailored care coordination.

Delivering Health Care by Emphasizing Quality to Improve Care Coordination

PHM often focuses on vulnerable populations with chronic conditions who lack care plans or fall through gaps in care transitions in the fragmented healthcare care system, and not all Americans have access to healthcare or pursue obtaining healthcare insurance. When primary care becomes ignored or delayed, for whatever reason, healthcare costs will rise simply because undesirable conditions and chronic diseases are not prevented or managed. To prevent this unhealthy situation, the health sector continues to develop integrated care networks (IDNs) where primary care, hospitals, and post-acute care are directly aligned. The NCQA refers to Integrated care networks as provider systems coupled with various sites of care able to provide a health insurance plan delivering health care services in a specific geographic area. (NCQA, 2019) Two other models of healthcare delivery are Accountable Care Organizations and Patient-Centered Medical Homes. Both care delivery models serve as examples of provider reimbursement directly tied to positive health outcomes for priority at-risk populations.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) became a PHM health option supported by infrastructure flexibility permitted within the Affordable Care Act framework. ACOs are networks of providers who coordinate whole patient centered care to patients, with the primary care physician (PCP) at the center of the network (Lapointe, 2019). ACOs rely on the coordinated care of populations to reduce redundant care and decrease unnecessary tests and treatments. Doctors who choose to form an ACO must meet stringent government requirement including having at least 5000 assigned beneficiaries, a formal legal structure to receive and distribute shared savings, integrating processes that promote evidence-based medicine, and reporting and assessing necessary data for quality, cost metrics and coordinated care outcomes (NCQA, 2020, Strategic Management Services, 2012). The physician benefits are both managerial and financial and can lead to reduced patient costs and better outcomes. Practitioners must meet established clinical and performance benchmarks for their patients to receive any monetary rewards, so a significant monetary risk is involved. The Medicare Shared Savings Program relies on 33 Quality Indicators to improve population health outcomes as quality indicators for ACOs (CMS, n.d.).

WHAT IS AN ACCOUNTABLE CARE ORGANIZATION? (CMSHHSGOV).

Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH), which predate ACOs, can easily be confused with ACOs, but their approach is for individual practices and not a network of providers. PCHMs can be described as multiple providers under one organization banner which offers interdisciplinary, community-based primary care teams that provide culturally informed patient-centered care (Primary Care Innovations, 2020).

In 2020, The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) recognized 13,000 practices with 67,000 clinicians (NCQA, 2020). Applicant organizations must deliver primary care following five core functions (patient-centered, comprehensive, coordinated, accessible, and with a quality and safety focus) to be considered a PCMH. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) offers a certification option with three levels of recognition (1 to 3) which if completed successfully has the potential added benefit ofincreasing reimbursement rates. There are many sophisticated models and pathways for PHM, but they all encourage financially tying patient outcomes to providers’ reimbursement to achieve significant savings (Kaufman et al. 2019). Both ACOs and PCMHs have the eligibility option to participate in alternative payment systems.

Virtual Care/Telehealth

The adoption of technological innovations may well be remembered as one of the outstanding contributions of PHM to improving access and population health outcomes. Often overlooked, under-utilized, and underappreciated, the rise of virtual care, also known as telehealth, helped solve the consumer dissatisfaction dilemma by offering instant access and added convenience. Virtual care can refer to telemedicine or e-medicine, digital health, or any of the other terms used to explain the process of communication between a provider and a patient that does not occur face-to-face and in the same location (Hewitt, 2021).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth was utilized and considered appropriate for rural health care where specialists could be consulted to aid small community hospital physicians (Raths,2020b). Telehealth also helped provide behavioral health (mental health) care that requires consistent and regular interactions with appropriately trained health professionals when patients and clients could not meet with their health practitioner. Due to the limited access to hospitals and primary care providers during the pandemic, the health sector pivoted quickly to expand virtual care options (Landi, 2020). A recent study reported a 63-fold increase in Medicare telehealth utilization during the pandemic period that replaced health appointments that would have otherwise been face-to-face (US DHHS, 2021). Both government and proprietary insurance companies responded to the situation by either adding or increasing their health provider compensation for diverse digital and other types of patient interactions (Telehealth.hhs, n.d.).

Evelyn is an 88-year-old retired widow living in the small community where she has spent her entire life. She is a diabetic with high blood pressure and has a daughter nearby who checks in regularly. Evelyn also participates in the local Meals-on-Wheels program. A few years ago, Evelyn’s primary care physician enrolled her in the community hospital’s “Aging Gracefully Today” virtual care program. As part of that senior initiative, a geriatric team of health providers monitors her regularly where she receives a weekly check-in via mobile phone from a care provider who has already received her daily insulin (A1c) count and BP metrics from the monitoring devices attached to the hospital’s system.

Evelyn’s care coordinator notices she seems extremely out of breath, appears very frail and shows a high BP reading. She texts an available care manager completing appointments and schedules a quick face-to-face check-up. All these interactions are recorded in the electronic medical record real time and are also available to Evelyn’s primary care physician. If a major change in health status occurs, the care coordinator notifies her daughter. This seamless patient-provider interaction is the result of technological innovations that have become routine to improve the continuum of care.

The sophistication of today’s health systems’ IT platforms and the integrated use of health data analytics drawing on diverse and real-time data have combined to establish PHM as an evidence-based model for cost-effective positive health outcomes.

Innovative PHM Solutions for Effective Healthcare Delivery Systems: Managing Relationship between Cost and Improved Outcomes

Not all quality performance improvement initiatives designed for vulnerable populations concentrate on improving care coordination to improve costs. Efforts to focus on improving the overall infrastructure of care can yield both health care savings and better outcomes if managed correctly.

Value Over Volume Transformations

The concept of value over volume remains a major PHM innovation. Why? Because the alternative payment systems used for capitated payment arrangements, accountable care, medical homes, and episodic or bundled payments align cost risk among the payor, provider, and the patient. All aim to restructure payments in a way that financially incentivizes low-cost, high-value care (American College of Physicians, n.d). Provider reimbursement options, incentives, and penalties strive to encourage optimum quality that will yield positive priority population health outcomes over time. PHM ensures that performance improvement continues to be embedded in all health care. Major healthcare organizations including the American Medical Association recently urged the U.S. Congress to increase adoption rates for alternative payment systems across the country (Hagland, 2022).

Improving Patient Engagement Outcomes via Meaningful Consumerism

With the recent rise of consumerism, patient and consumer engagement have become even more essential as health providers and systems seek to form positive and lasting relationships with patients. One recent criticism, often repeated, compares the ease of banking in today’s virtual world with the multitude of steps (or clicks) needed to navigate an appointment with a specialist in our complicated health system. The idea is for healthcare to become digital-first for access (Siwicki, 2022). Yes, consumerism is convenience, convenience, and convenience, but it also requires informed decision-making. American patients have become consumers who want autonomy when selecting healthcare providers and control of provider interactions.

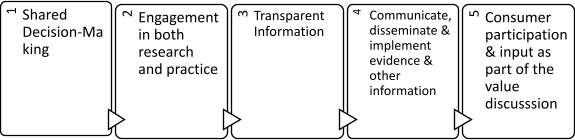

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) identified 5 elements of Meaningful Consumerism that serve as the criteria for positive outcomes between health providers and consumers/patients as presented in Figure 10 Meaningful Consumerism Elements (PCORI, 2019).

Figure 10

Meaningful Consumerism Elements

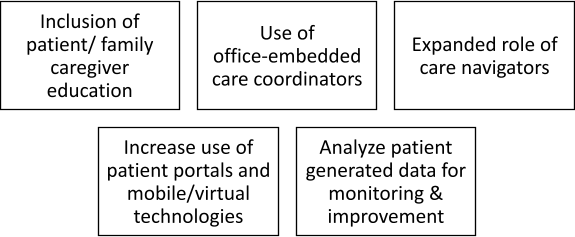

The PHM goal is always to create a value interaction that involves trust built on mutual communication and transparency of information between all parties. Successful health interactions require two-way communication, and patient engagement is crucial. Patient engagement, which refers to activities involving an individual in their own care (Graffigna & Barella, 2018) is determined by a patient’s capacity and capabilities. Each person’s capabilities are dependent on their resources, willingness, and self-efficacy, which is their belief that they have the confidence to do whatever change or action that is required to succeed. The individual’s capacity is based on a triangle of intersecting factors – person, environment, and engagement behavior (Sieck et al., 2019). For example, you may not be motivated to increase physical activity if you feel pressured for time, cannot walk, or run as far as the health provider suggests, or live in an area that has no park or sidewalks convenient and safe for walking. The likelihood of your cooperation and participation with the health provider will be limited. Patient experience, which is the consumer’s perception of the health experience, is another factor that can impact patient cooperation. Many individuals often struggle or do not follow their medication directions as outlined by the health provider (Iuga & McGuire, 2014). Data shows that if patients are dissatisfied with their experiences, whether it be with the treatment or a particular healthprovider, they often risk negative health outcomes by not complying or following directions. Patient satisfaction refers to their overall feelings and attitudes regarding their health expectations and outcomes. To ensure patient engagement and positive experiences, PHM relies on several evidence-based strategies to improve the patient health pathway as summarized in Figure 11.

Figure 11

Strategies for Improving Patient Engagement

Another interesting patient engagement technique that works well for individuals living with chronic disease and those transitioning from acute care is the use of self-management education (SME) programs (CDC, 2018). At-risk groups living with chronic conditions such as chronic pain, arthritis, or diabetes attend a series of interactive classes or workshops, some even provided virtually, and guided by a facilitator to learning day-to-day strategies and actual skills for coping with their symptoms and conditions. The overall goal is to improve self-efficacy and encourage self-reliance to manage their individual situation and eliminate unnecessary visits to emergency departments.

Adopting 21st Century Additional Care Options

“Health primarily happens outside the doctor’s office—playing out in the arenas where we live, learn, work and play,” as stated by National Coordinator Karen DeSalvo in 2014 (DeSalvo & Leavitt, 2019). For PHM, the challenge is to offer health care at the right time, in the right place, and with the right provider model. Other successful PHM care coordination strategies emerging during the last few years include:

- Adding non-traditional care sites in convenient locations to meet consumer demand. These include placing ambulatory care centers and urgent care centers in malls and pharmacy locations to expand the Continuum of Care options and meet consumer demands.

- Addressing transitions of care via upgraded care coordination initiatives with embedded patient coordinators, engaged patients, and encouraging self-management education programs.

- Piloting and enabling CMS innovative programs known as hospitals without walls or hospitals at home (Raths, 2020a). This allows PHM health providers to offer acute level health care in the home for the benefit of the patient with lower cost and better outcomes (Levine et al., 2020). These telehealth and virtual care-supported services may significantly expand home healthcare and remote patient monitoring in the future.

- Strengthening collaborations and partnerships to reduce and eliminate health inequities and disparities by investing with both traditional and non-traditional partners in local community infrastructures such as building safe and affordable housing. Encourage the co-production of health aligning disparate and primary health stakeholders including nonprofit, public, and proprietary, and private partnerships (Gray, 2017). The goal of this macrosystem integration is to align all necessary resources to improve health for all (Wagner & Hewitt, 2021).

Overall, these latest initiatives and innovations continue to seek the PHM goal of offering the right care, at the right time and place by the right health provider.

Summary

Population Health Management seeks to meet the health needs of all Americans especially those populations that are vulnerable or at risk for poor health status. The integrated focus on healthcare delivery access, quality of care, and cost- effectiveness sets the PHM approach apart from previous health sector strategies. PHM characteristics can be summarized in the following list of strategies.

- Shifts from an individual patient to a defined population focus

- Aligns outcomes with payment models

- Emphasizes both quality and safety to create value

- Integrates health promotion elements throughout

- Expands the Continuum of care

- Relies on new models to ensure quality and cost reduction

- Adopts innovation and technology options to improve care

The PHM focus differs from global, public, and community health approaches and continues its 21st-century role as a health sector model for all Americans.

Key Words

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) – ACOs are networks of providers who come together to provide whole- patient-centered care to patients, with the primary care providers (physicians, physician assistants or nurse practitioners) at the center of the network.

Alternative Payment System – A payment system that caninclude risk for the provider and the payor and may include incentives and penalties.

Community health – Refers to the health status of a defined group of people and the actions and conditions, both private and public (governmental), to promote, protect, and preserve their health.

Community health needs assessment (CHNA) – A systematic process, conducted by a hospital, involving the community to identify and analyze community health needs and assets, prioritize those needs, and then implement a plan to address significant unmet needs.

Continuum of Care – Describes a system process that guides and tracks patients over time through a comprehensive array of health services spanning all levels and intensity of care.

Consumerism– People proactively using trustworthy, relevant information and appropriate technology to make better-informed decisions about their healthcare options.

Culture of Health – The Culture of Health: Action Framework combines essential components of community, public, global, and population health approaches by establishing 10 principles that provide a foundation for four action steps.

Disease Prevention – A combination of three proactive approaches to prevent the occurrence of an adverse health event including vaccinations, screenings and managing post- diagnosis.

Electronic Health Record (EHR) – A digital, universal repository of patient’s information.

Global health – Collaborative transnational research and action for promoting health for all.

Health – state of complete physical, mental, and social well- being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

Health data analytics – Focuses on the technologies and processes that measure, man- age, and analyze healthcare data.

Health in All Policies (HiAP) – A collaborative approach that brings together policymakers and practitioners from all sectors related to SDOH under the assumption that all multisectoral policies affect health outcomes.

Health promotion – An approach of enabling people to increase control over their health and its determinants, and thereby improve their health

Hotspotting – A strategy of identifying those at-risk patients with multiple comorbidities who overuse emergency treatment because of a lack of coordinated care and aligning them with doctors, other caregivers, and social service providers, to prevent rehospitalizations.

Integrated Delivery Networks – A single organization or group of organizations working together in an organized coordinated effort as a network or providers for population health.

Managerial Epidemiology – Application of various data into information for population health decision-making.

Patient – Centered Medical Homes – Multiple providers under one organizational banner created with the intention of reducing costs while improving patient outcomes.

Patient engagement – Refers to activities to involve an individual in their own care.

Patient experience – The sum of a consumer’s perception of the entire interactive health experience.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) – The Affordable Care Act provides for numerous rights and protections that make health coverage fairer and easier to understand and more affordable.

Patient satisfaction – Refers to a consumer’s overall feelings and attitudes regarding their health expectations and outcomes.

Populations – A term that refers to not just individuals or groups, but where people live, work, and play in communities.

Population health – The health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.

Population health management – PHM is the process of improving clinical health outcomes of a defined group of individuals through improved care coordination and patient engagement supported by appropriate financial and care models.

Public health – The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promotingphysical health and efficiency through organized community efforts.

Risk – The probability that an event will occur.

Risk Score – Combination of risk factors that compute a likelihood of an event occurring in a short timeframe.

Risk factor – It is an exposure that is associated with a disease or a condition, without certainty.

Risk segmentation – Uses current and prospective medical costs, health status, attitudes, level of healthcare engagement and various other factors to select individuals from a population.

Risk stratification – A systematic process for identifying and predicting patient’s risk levels relating to healthcare needs, services, and care coordination with the goal of identifying those at highest risk and managing their care to prevent poor outcomes.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) – Conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources and other influential factors.

Triple Aim – Addresses simultaneously the population health issues of access, quality, and cost.

Upstream, midstream, downstream – Upstream issues address the SDOH. Mid- stream issues refer to educating individuals to improve their condition and include factors related to individual-level behavior change such as promoting healthy eating, healthy family relationships, and exercise, and downstream issues include costs of treating and expenses such as treatment of chronic and relapsing conditions and related disease complications.

Value-based care – Requires quality services, positive health outcomes, and cost re- duction, and may use incentives as part of an alternative payment system.

Virtual Care/Telehealth – Digital interactions between a health provider and patient.

Volume-based care – Care based on cost associated with single EOC with payment regardless of quality.

Questions:

Question #1 – Name the national health policy that served as the major catalyst for population health management.

Question #2 – The PPACA requires all hospitals to complete a Community Health Needs Assessment or risk a fine of $50,000.

Question #3 – Which of the following documents includes the national public health objectives that help guide population health management?

a. WHO Definition of health

b. Healthy People 2030

c. Community Health Needs Assessment.

d. None of the above

Question #4 – Draw the diagram that identifies the three major aims of population health management and label correctly.

Answers:

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (PPACA)

True.

B. Healthy People 2030

Access, Quality and Cost

References

Ahmad, F. & Anderson, R. (2021). The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. Journal of the American Medical Association,325(18), 1829-1830. doi:10.1001/ jama.2021.546

American College of Physicians (n.d.). Alternative payment models. APConline. https://www.acponline.org/practice-resources/business-resources/payment/medicare-payment-and-regulations-resources/macra-and-the-quality-payment-program/alternative-payment-models-apms#:~:text=Common%20types%20of%20APMs%20include,Pa yment%20Learning%20%26%20Action%20Network

American Hospital Association (AHA). (n.d.). What is population health management? https://www.aha.org/center/population-health-management

American Public Health Association (APHAa). (n.d.) Health equity. https://www.apha.org/topics-and issues/health-equityU.S. Healthcare System 44

American Public Health Association (APHA). (2020.) Health in All Policies. https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-in-all-policies

Beaglehole,R.,&Bonita,R.(2010).Whatisglobal health? Global Health Action, 3,10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142.

Bernell, & Howard, S. (2016). Use your words carefully: What is chronic disease? Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00159

Berwick, D., Nolan, T. & Whittington, J. (2008). The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Affairs, 27(3), 759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

Blumenthal, D., Collins, S., & Fowler, E. (2020, February 26). The Affordable Care Act at 10 Years: What is the effect on health care coverage and access? TheCommonwealthFund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal- article/2020/feb/aca-at-10-years-effect-health-care-coverage- access

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports; 129 Suppl 2:19-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S206

Carlson, L. M. (2020). Health is where we live, work and play — and in our ZIP codes: Tackling social determinants of health. The Nation’s Health. 50 (1) 3 http://www.thenationshealth.org/content/50/ 1/3.1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2008). Community health and program services (CHAPS): Health disparities among racial/ ethnic populations. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), (2016). Health in all policies. Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy. https://www.cdc.gov/policy/hiap/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), (2018). Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). https://www.cdc.gov/ phlp/publications/topic/hipaa.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), (2018). Managing Chronic Conditions: Self-Management Education Programs for Chronic Conditions https://www.cdc.gov/learnmorefeelbetter/programs/ general.htm U.S. Healthcare System 46

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), (2020).Healthy People 2030. National Center for Health Statistics.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthypeople/hp2030/hp2030.htm

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. (2021, December 15). National Health Expenditure: Health Sheet:Historical NHE2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/ NHE-Fact-Sheet

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. (n.d. ) ACO shared savings quality measures. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service- payment/sharedsavingsprogram/downloads/aco-shared- savings-program-quality-measures.pdf

Champion, VL. & Skinner, CS. (2008). The health belief model. In K. Glanz, BK Rimer, K. Viswanath (ed.),Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice.4th ed. (pp. 45-66). Jossey Bass.

Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health; Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/ final_report/csdh_finalreport_2008.pdf

Fleming, S.T. 2013. Managerial epidemiology: It’s about time! Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 4(2), 148-149.

DeSalvo, K. & Leavitt, M.O. (July 8, 2019). For an option to address social determinants of health, look to Medicaid. Health Affairs. https://www.apha.org/ topics-and-issues/health-in-all-policies

Dicent Taillepierre, J., Liburd, L., O’Connor, A., Valentine, J., Bouye, K., McCree, D., Chapel, T., & Hahn, R. (Jan-Feb 2016). Toward achieving health equity: Emerging evidence and program practice. Journal of Public Health Management Practice, 22 Suppl 1, S43-49. doi: 10.1097/ PHH.0000000000000375.

Goldstein, F. Shephard, V. & Duda, S, (2016). Policy implications for population health: Health promotion and wellness. In D. Nash, A. R. Fabius, A. Skoufalos, J. Clarke, & M. Horowitz (Eds,). Population health: Creating a culture of wellness, (pp. 43-58). Jones & Bartlett Publishing.

Google Inc. (2014). Flu trend estimates. https://www.google.com/publicdata/ explore?ds=z3bsqef7ki44ac_ U.S. Healthcare System 48

Graffigna, G. & Barello, S. (2018). Patients prefer adherence, 12, 1261-1271. https://doi: 10.2147/PPA.S145646

Gray, M. (2017). Value based healthcare. BMJOnline, 356, j437. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j437

Hagland, M. (2022, February). Healthcare associations call on congresstospurAPMadoption.HCInnovation. https://www.hcinnovationgroup.com/policy-value-based-care/ alternative-payment-models/news/21255759/healthcare- associations-call-on-congress-to-spur-apm-adoption

Health Information Network (HIN), (2019). Patient engagement in 2019: Positive payoffs from patients activated in their healthcare. Health Information Network. http://www.hin.com/library/registerPatientEngagement2019.html

Hewitt,A.(2021).Populationhealthmanagement:A framework for the health sector. In A. Hewitt, J. Mascari, & S. Wagner (Eds.), Population health management: Strategies, tools, applications, and outcomes (pp.3-20). Springer Publishing Company.

Hewitt, A. (2021). Population health models – Part II: Care coordination continuum, behavior change, patient engagement, and telehealth. In A. Hewitt, J. Mascari, & S. Wagner (Eds.), Population health management: Strategies, tools, applications, and outcomes (pp. 155-172). Springer Publishing Company.

HIPAAJournal.(2020).WhatistheHITECHact? https://www.hipaajournal.com/what-is-the-hitech-act/

Institute for Health Improvement (IHI), (2022). The IHI triple aim. http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/ default.aspx

Institute for Health Improvement (IHI). (n.d.) Resources: Pathways to population health http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Population-Health/Pages/ Resources.aspx

Institute for Work and Health (IWH). (2015, April). What researchers mean by primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. https://www.iwh.on.ca/what-researchers-mean-by/primary- secondary-and-tertiary-prevention

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). (2020). Community Health Needs Assessment for Charitable Hospital Organizations Section 501(r)(3). https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/community-health- needs-assessment-for-charitable-hospital-organizations- section-501r3

Iuga, A. O., & McGuire, M. J. (2014). Adherence and health care costs. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 7, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.2147/ RMHP.S19801

Jha, A. (2019, August 6). Population health management: Saving lives and saving money?

Journal of the American Medical Association,322(5), 390-391. https://doi:10.1001/jama.2019.10568.

Johri. N. (2021). Health data analytics for population health management. In A. Hewitt, J. Mascari, & S. Wagner (Eds.), Population health management: Strategies, tools, applications, and outcomes (pp. 79-101). Springer Publishing Company.

Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology. (2012) Report of the 2011 Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology. American Association of Health Education.

Kamal, R., McDermott, D., Ramirez, G., Cox, C. (2020, December 23). How has U.S. spending on healthcare changed over time? Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s- spending-healthcare-changed-time/

Kaufman, B. G., Spivack, B. S., Stearns, S. C., Song, P. H., & O’Brien, E. C. (2019). Impact of accountable care organizations on utilization, care, and outcomes: A systematic review. Medical Care Research and Review, 76(3), 255-290.

Kindig, D., & Stoddart, G. (2003). What is population health? American Journal of Public Health, 93(3), 380–383. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.3.380

LaMorte, W. (2019).Transtheoretical Model of Change/ Stages of Change. Boston University School of Public Health. https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/ mph-modules/sb/behavioralchangetheories/ BehavioralChangeTheories6.html

Landi, H. (2020, December 23). Doctor on demand, Harvard study finds telehealth surge driven bybehavioral health, chronic care illness visits. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/doctor-demand-study-finds-covid-19-telehealth-surge-driven-by-behavioral healthchronicmkt_tok=eyJpIjoiTWpneE1qVTJNV0prT1RWaSIsInQiOiJTbkpnOGltZXZOVjU1ZXBBTGV4TE5JNU1tVEhPOHpFSWNQODkyZFRJVEs0WVgxbUF4d3VvK1gwXC9JMFllM2N4ZlVjS

0tocEdxTWNWWFN2Sko0MVBoS21DdzBMRlErOFZocVJqdH VEa3ZaTmxXRjUxcUg4NXpOXC9TMEhoMWxnRTZUIn0%3D &mrkid=931686

Lapointe, J .(2019).Top 10 Accountable Care Organizations by shared savings in 2019.Revcycle Intelligence. https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/ top-10-accountable-care-organizations-by-shared-savings- in-2019

Levine, D., Ouchi, K., Blanchfield, B., Saenz, A., Burke, K., Paz, M., Diamon, K., Pu, C., & Schipper, J. (2020) Hospital-Level care at home for acutely ill adults: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(2), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0600

Looker Data Sciences, Inc. (2020). Healthcare analytics. Looker. https://looker.com/definitions/healthcare-analytics

Magesh, S., John, D., Li, W., Li, Y., Mattingly, A., Jain, S., Chang, E., & Ongkeko, W. (2021). Disparities in Covid-19 outcomes by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open, 4(11), e2134147. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2021.34147.

Manatt Health & Phelps & Phillips, LLP (2019, February 1).

Medicaid’s role in addressing social determinants of health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/02/medicaid-s- role-in-addressing-social-determinants-of-health.html

Manchanda, R. (January 17, 2019) Making sense of the social determinants of health http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/making-sense-of-the- social-determinants-of-health

Mascari, J. & Hewitt, A. (2021). Population health decision- making: Risk segmentation, stratification, and management. In A. Hewitt, J. Mascari, & S. Wagner (Eds.), Population health management: Strategies, tools, applications, and outcomes (pp. 103-119). Springer Publishing Company.

McIntire, R., McAna, J. & Oglesby, W. (2021). Epidemiology. in

D. Nash, A. Skoufalos, R. Fabius, & W. Oglesby, (Eds.), 3rd ed., Population health: Creating a culture of wellness (pp.23-46). Jones and Bartlett Learning.

McKenzie, J., Pinger, R., Kotecki, J. (2005). An Introduction to Community Health. (p.5) Jones and Bartlett Publishers

Merck, A. (2018, October 08). The Upstream-Downstream Parable for health equity. Salud America. https://salud-america.org/the-upstream-downstream- parable-for-health-equity/

Nash, D.B. (2012) The Population Health Mandate: A Broader Approach to Care Delivery. The Four Pillars of Health in A Boardroom Press Special Edition. http://populationhealthcolloquium.com/readings/ Pop_Health_Mandate_NASH_2012.pdf

National Academy of Medicine (NAM, 2000). To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Academy of Medicine (NAM, 2001). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

National Commission on Quality Assurance (2016). Population health management: Roadmap for integrated delivery networks https://www.ncqa.org/wp- content/uploads/2019/11/20191216_PHM_Roadmap.pdf

National Priorities Partnership (2008). National Priorities and Goals: Aligning Our Efforts to Transform America’s Healthcare. National Quality Forum http://www.qualityforum.org/Setting_Priorities/ National_Priorities_Partnership_-

_Call_for_Organizational_Nominations.aspx.Availablevia email at .info@qualityforum.org

National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA). (2020, August 12). Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH). National Committee for Quality Assurance. https://www.ncqa.org/programs/health-care-providers- practices/patient-centered-medical-home-pcmh/

New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst (NEJM) (2017,January 1). What Is value-based healthcare? https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/ CAT.17.0558 Noonan, A., Velasco-Mondragon, H., & Wagner, F. (2016).

Improving he health of African Americans in the USA: An overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Review, 37,12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2018 ). Healthy People 2030 Framework. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People/ Development-Healthy-People2030/ Framework#:~:text=Report%20biennially%20on%20progress%2 0throughout,%2C%20data%2C%20and%20evaluation%20needs

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2021). History of Healthy People. https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/ healthy-people/about healthy-people/history-healthy-people

Ottawa Charter (1986). Ottawa Charter 1986. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ ottawa/en/

Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). (Nov 12, 2019). By consumers, for consumers: Building capacity and partnerships to enhance patient-centeredness. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/ 2015/consumers-consumers-building-capacity-and- partnerships-enhance-patient

Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative. (August 20, 2020). Primary care innovations and PCMH map by state. https://www.pcpcc.org/initiatives/state

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPAC). (2010). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. HealthCare.gov. https://www.healthcare.gov/ glossary/patient-protection-and-affordable-care-act/

Prochaska, JO., Redding, CA., & Evers, KE. (2008). The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In K. Glanz, BK Rimer, K. Viswanath (ed.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice.4th ed. (pp. 97-121). Jossey Bass.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2015, February 20). What is the Population Health Approach? https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health- promotion/population-health/population-health-approach/ what-population-health-approach.html#historyo

Raths, D. (2020, November 25)a. CMS Expands Hospital-at- Home program. Healthcare Innovation. https://www.hcinnovationgroup.com/population- health-management/remote-patient-monitoring-rpm/news/ 21164286/cms-expands-hospitalathome-program

Raths, D. (2020, December 28)b. Highmark adds tele-addiction, peer support services to SUD recovery approach. https://www.hcinnovationgroup.com/ population-health-management/behavioral-health/article/ 21204045/highmark-adds-teleaddiction-peer-support-services- to-sud-recovery- approach?utm_source=HI+Daily+NL&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=CPS201231003&o_eid=6978A6266356F5Z&rdx.ident%5Bpull%5D=omeda%7C6978A6266356F5Z&oly_enc_id=69 78A6266356F5Z

Ray, R. (2020, April 9). Why are Blacks dying at higher rates from COVID-19? The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/04/ 09/why-are-blacks-dying-at-higher-rates-from-covid-19/

Roberts, B. (2017). Integration vs. interoperability: What’s the difference? SIS BLOG. https://blog.sisfirst.com/integration-v-interoperability-what-is- the-difference.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). (2020). Culture of Health: Taking action. https://www.rwjf.org/en/cultureofhealth/taking-action.html

Saha et al., (2017). Pathways to population health: An invitation to health care change agents. Boston: 100 million healthier lives convened by the Institute for Health Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Population-Health/Documents/PathwaystoPopulationHealth_Framework.pdf Scherpbier, H., Walsh, K., Skoufalos, A. (2021) Population health data and analytics. in D. Nash, Skoufalos, R. Fabius, & W. Oglesby, (Eds.), 3rd ed., Population health: Creating a culture of wellness (pp.114-135). Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Sieck, C., Walker, D., Sheldon, R., & McAlearney, A. (2019, March 13). The Patient Engagement Capacity Model: What factors determine a patient’s ability to engage? New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst. https://nam05.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcatalyst.nejm.org%2Fpatient-engagement-capacitymodel%2F&data=01%7C01%7Canne.hewitt%40shu.edu%7 C9ae44a0dba4c46706a1208d6b513b4c5%7C51f07c2253b744dfb97ca13261d71075%7C1&sdata=OSbrk3NbO1dierYT%2BcO Nz6RZmTXpk6%2BsOzxEAtI%2BOZc%3D&reserved=0

Siwicki, B. (2022). Like banks, healthcare will become digital- first in 2022, Zoom healthcare leader says. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/banks- healthcare-will-become-digital-first-2022-zoom-healthcare- lead-says

Strategic Management Services, LLC (2012, April). Accountable Care Organizations Regulations: ACO Final Rule Summary. https://www.compliance.com/resources/accountable-care-organizations-regulations-aco-final-rulesummary/#:~:text=Table%201%3A%20General%20Eligibility%20Requirements&text=Enter%20a%20three%2Dyear%20participation,obligations%20under%20the%20participation%20agreement.&text=Be%20able%20to%20provide%20care,be%20eligible%20fo r%20shared%20savings.

Surendrank, B. (n.d.)Use of data analytics to improve Continuum of Care. KP INSIGHT (Data & Analytics Group) Kaiser Permanente. http://or.himsschapter.org/sites/himsschapter/files/ ChapterContent/or/ OR19_Use_of_Data_Analytics_to_Improve_Continuum_of- Care.pdf

Telehealth/Health and Human Services (n.d.) Billing for telehealth during COVID-19. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/billing-and-reimbursement/?gclid=Cj0KCQiA3-QBhD3ARIsAHuHT67di XNbsvpHjuau3iaKc2x8XLphw8YzitJ- odK1L5HA6fSk4cOCNFsaAtrFEALw_wcB

The Commonwealth Fund. (November 2016). New survey of 11 countries, U.S. adults still struggle with access to and affordability of health care. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal- article/2016/nov/new-survey-11-countries-us-adults-still- struggle-access-and

TheEqualityandHumanRightsCommission(2018). Understanding equality: What is equality? https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/secondary-education-resources/useful-information/understanding- equality

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (n.d.). Social determinants of health: Interventions and resources. Healthy People2020.https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions- resources

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021, December). New HHS study shows 63-fold increase in Medicare telehealth utilization during the pandemic. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/12/03/new- hhs-study-shows-63-fold-increase-in-medicare-telehealth- utilization-during-pandemic.html

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (n.d.) Diversity and inclusion definitions https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/ administration/admabout/diversity_inclusion/definitions

Vermont Department of Health. (March 30, 2018). Creating cross-sector action and accountability for health in Vermont: Guidance from a rural state. https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ pdf/ADM_CoH_Guide.pdfWagner, S. & Hewitt, A. (2021). Collaborations and co- production of health. In Population Health Management. In A. Hewitt, J. Mascari, & S. Wagner (Eds.), Population health management: Strategies, tools, applications, and outcomes (pp. 211-228). Springer Publishing Company.

Winslow, E. (1920). The untilled fields of public health. Science, 51(1306), 23–33.

World Health Organization (WHO). 1946. Constitution of the World Health Organization https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution

World Health Organization (n.d.). Social Determinants of Health: Health Equity. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of- health#tab=tab_3