4

Public Health, Prevention, & Wellness

Carissa Ruby Smock, PhD, MPH

Marie Bakari, EdD, DBA

Kimberly Scott, DBA, MPH

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” – World Health Organization

Learning Objectives

- To define public health, wellness, and prevention.

- To review the history and development of the public health system.

- To describe the evidence base and practicality of how public health saves lives and increases the sustainability of the U.S. healthcare system through prevention and wellness.

- To examine the current public health structure including health care intersections within the U.S. healthcare system.

- To discuss the potential for growth of public health, wellness, and prevention within the U.S. healthcare system.

Introduction

Prevention and wellness save lives and increase the sustainability of the U.S. healthcare system, improving the public’s health (Levine et al., 2019; Marvasti & Stafford, 2012; RHIhub, 2021). This chapter begins by introducing the structure and mission of public health in the U.S. including definitions and applications of public health, prevention, and wellness language, concepts, and constructs. Next, current structures are explored, concluding with the potential for growth of public health, wellness, and prevention within the U.S. healthcare system. Applications will be presented on the role and potential roles within the U.S. healthcare system as well as responsibilities of leaders, researchers, and practitioners. Guidance and approaches will be offered for each role. The aim of this chapter is to provide readers with the evidence base and practicality of how public health saves lives and increases the sustainability of the U.S. healthcare system through prevention and wellness.

Structure and Function of U.S. Public Health Service Sector

“Neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” – C. Wright Mills

To appreciate what the public health service sector has become, it is best to reflect on the history of its development over the last 200 years. Terris (1944) described the 1798 Congressional Act as an unprecedented attempt to fund public health in the 18th century. An Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen was signed into law on July 15 of 1798. At a rate of 20 cents per month of every sailor’s pay, all ships’ captains originating in foreign ports had to pay into the newly created public fund upon docking in U.S. harbors. Merchant ships were subjected to similar fees for licensing. The monies collected were distributed by the President of the United States to pay for the care of seamen who had been disabled; funds were distributed to hospitals and other suitable care facilities. Terris argued the act was the beginning of socialized medicine. On the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS, 2022a) website, the 1798 law is described as the forerunner of the public health service as it exists currently.

The origins of the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are linked to Abraham Lincoln in 1862 (HHS 2022a). President Lincoln appointed a scientist to serve in the newly created Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Chemistry; this bureau later became the FDA when the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act was passed (NA, 2018). During the 1870s, a hygienic laboratory was established at Staten Island, New York. The Supervising Surgeon (currently, the Surgeon General) was appointed in 1871 to oversee the network of institutions that made up the Marine Hospital Service. By the 1880s, the National Quarantine Act shifted the responsibilities of controlling disease outbreaks to the Marine Hospital Service. Scientists of this era were keenly aware of the link between sea travel and disease transmission and spread.

Changes in immigration policies at the end of the 19th century sparked needed adaptations to the Marine Hospital Service (HHS, 2022a). Through the passage of legislation, the Marine Hospital Service was charged with medically clearing immigrants who arrived on the shores and borders of the United States. With these new responsibilities and the shift in services provided by this entity, the organization went through a few name changes between 1902 and 1912, when it was ultimately named the Public Health Service.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the U.S. government changed the priorities of the Public Health Services and expanded oversight responsibilities (HHS, 2022a). In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act was one such expansion which broadened the accountability of the nation’s food and pharmaceutical manufacturers to the FDA; cosmetics were added to the FDA’s oversight responsibilities in 1938 by congressional act. Curbing the exploitation of children resulted from President Roosevelt’s insistence to create the Children’s Bureau. Later, in 1921, the precursor of the Indian Health Services, the Bureau of Indian Affairs Health Division, was created. The National Institute of Health was formally created in 1930; this agency stemmed from the hygienic laboratory in New York and was later changed to the National Institutes of Health. The Federal Security Agency was created in 1939 to administer social insurance, health, and education (HHS, 2022a).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2018), formerly the Communicable Disease Center, was established in 1946 to prevent the spread of malaria, a mosquito-borne disease. This agency proactively expanded its focus to other communicable diseases. From the humble beginnings of occupying a single floor in a building in Atlanta, Georgia, the CDC evolved over the years and spawned the Department of Health and Human Services.

Throughout the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st, there were numerous adjustments to address and manage emerging challenges, inter- and intra-departmental reorganizations, and the creation of new entities (HHS, 2022a). These changes included:

1950s

· Department of Health, Education, and Welfare – 1953

· Salk polio vaccine licensed – 1955

1960s

· Conference on Aging – White House, 1961

· Migrant Health Act – 1962

· Surgeon General’s report on Smoking & Health – 1964

· Medicare, Medicaid, nutritional and social programs for the aging, Head Start program – 1965

· Smallpox Eradication program, health center programs for migrants and communities – 1966

1970s

· National Health Service Corp – 1970

· National Cancer Act – 1971

· Child Support Enforcement and Paternity Establishment Program – 1975

· Health Care Financing Administration – 1977

· Department of Education established, Department Health and Human Services (formerly HEW)

1980s

· AIDS identified as a disease – 1981

· National Organ Transplantation Act – 1984

· McKinney Act, JOBS program with federal support for childcare – 1989

1990s

· Human Genome Project, Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, CARE Act for HIV/AIDS – 1990

· Vaccines for Children program – 1993

· Social Security Administration became independent – 1995

· Welfare reform, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act – 1996

· State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) – 1997

· Ticket to Work, Work Incentives Improvement Act – 1999

2000s

· Human genome sequencing project published – 2000

· Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (formerly Health Care Financing Administration), response to anthrax attack – 2001

· Office of Public Health Emergency Preparedness – 2002

· Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act 2003

· Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans – 2008

2010s

· Affordable Care Act 2010

The structure, functional responsibilities, and federal support for the public health system has undergone dramatic changes in its short 240-year history. The collective efforts of the federal government, politicians, advocates, and scientists had a goal – preserve, protect, and improve the health of the U.S. population (Raghupathi & Raghupathi, 2020). The public health effort, albeit seemingly altruistic and virtuous, supports the nation’s economy, labor force, armed forces, capitalism, and the balance of global power. The work of the U.S. public health system relies on the dependable infrastructure, strategic preparation and planning, and control of logistics and supply chains for the adequate and timely delivery of support, services, and equipment.

The federal agencies identified thus far rely on strong infrastructure to enforce policy, administrate programs effectively to respond to public health threats and emergencies. For the purposes of this chapter, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA, 2022) definition best described the gamut of elements which constitute the nation’s systems.

Administrators at CISA provided this definition:

There are 16 critical infrastructure sectors whose assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, are considered so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof. CISA (2022), para. 1.

These federal agencies leverage infrastructure to support (a) state, tribal, territorial, and local health departments, (b) clinical care delivery systems, and (c) other government agencies unrelated to health. Private industry, private and non-profit associations, educational institutions, nursing homes, the media, and community-based organizations complete the network known as the public health system.

The people who work within the public health system collectively perform key functions in the United States; the functions performed are for the benefit of populations localities, cities, or states; individuals are diagnosed and treated by physicians and auxiliary medical staff in private offices, clinics, hospitals, or other facilities. In communities and territories across the nation, there is ongoing monitoring of the health status of populations. Agencies within the public health network investigate and diagnose hazards within communities; agencies have the authority to inform citizens of dangers and educate and empower people.

In response to the global problem of climate change, public health systems have had to adapt to responding to a greater number of weather-related emergencies. This begs the question: what constitutes preparedness for emergencies? This topic was the subject of research published in BMC Public Health (see Khan et al., 2018). Khan et al. (2018) examined numerous frameworks for public health preparedness, including models proposed by the World Health Organization and the United Nations. The findings in this study brought attention to the inherent need for “empirically derived and contextually-relevant evidence to inform public health actions for local/regional public health agencies remains a knowledge gap,” (Khan et al., 2018, p. 2).

Public health agencies are involved in policy development and planning, enforcement of laws and regulations, and guaranteeing the competency of the healthcare workforce. Citizens rely on public health agencies to establish and regulate quality, accessibility, and effectiveness of health services. When health problems result from disasters (man-made or natural), the public health system becomes an essential conduit between people (population in the affected area) and services that sustain health and wellness temporarily until life normalizes. Lastly, researchers contribute to the growing body of medical science through discovery and innovation.

Consider the history of diseases, epidemics, pandemics, climate change, and wars in the United States and the impact of the public health system is both prolific and economic. Polio, smallpox, malaria, swine flu, lyme disease, HIV/AIDS, and COVID-19 are some of the well-known incidents of ailments that affected populations across the country in past centuries. The public health system, its leaders, patrons, supporters, employees, and activists remain prepared to contribute knowledge and skill to promote healthy lifestyles, respond to infectious diseases, and keep populations healthy.

There is a strong and direct association between federal expenditures on health and economic performance and development (Raghupathi & Raghupathi, 2020). Data from industrialized countries showed for every 1 year added to life expectancy, there was a concomitant increase of 4% to gross domestic product, a key economic indicator. Based on an examination of these data and data from around the globe, Raghupathi and Raghupathi determined higher per capita income contributes to healthier outcomes for the population.

Racism: A Public Health Threat

In 1988, the National Academy of Medicine (then Institute of Medicine) published a report called The Future of Public Health (Perry, 2024). The writers of the report identified assessment and policy development as core functions of public health departments. Additionally, the report served as a call to action for government representatives to take responsibility for promoting health and well-being while responding to emerging and persistent threats. In 1995, U.S. Public Health Service members identified 10 Essential Public Health Services based on the core functions to inform how state and local health systems could be organized, set performance and accreditation standards, and guide curricular development for schools. In 2020, public health officials revised the 10 Essential Public Health Services to include recognition of social inequities on community health.

A public health threat refers to any circumstance, agent, or event that poses a danger to a community’s overall health and well-being. These threats can arise from various sources, including infectious diseases, environmental hazards, behavioral factors, or other conditions that can potentially cause harm on a large scale. Public health threats include infectious disease outbreaks (such as pandemics), exposure to pollutants or toxins, inadequate healthcare services, natural disasters, and unhealthy lifestyle choices. Public health threats can lead to widespread illness, injury, or death, and they often require coordinated efforts from public health organizations, governments, and communities to mitigate and address their impact. Public health officials design interventions aimed at preventing, controlling, or managing these threats to protect and promote health communities.

Racism is defined as a comprehensive system encompassing structures, policies, practices, and norms that assign value and opportunities based on physical appearance or skin color. Representatives of the American Public Health Association (https://www.apha.org) claim that racism leads to unjust advantages for some individuals and disadvantages for others throughout society. Both interpersonal and structural racism have detrimental effects on the mental and physical well-being of millions of people, hindering their ability to achieve optimal health and impacting the overall health of the nation.

Extensive research reveals that centuries of racism in the United States have profoundly and negatively affected communities of color. These effects permeate various aspects of society, influencing residence, education, work, worship, and recreation, resulting in inequities in accessing social and economic benefits like housing, education, wealth, and employment. These disparities, commonly known as social determinants of health, contribute significantly to health inequities within communities of color, placing them at higher risk for adverse health outcomes. There is a plethora of research linking racism and slavery in the United States to epigenetic changes; epigenetics is the study of modification of gene expression (see Jackson et al., 2018; Mulligan, 2021).

Data indicates that racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States experience elevated rates of illness and death across various health conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, obesity, asthma, and heart disease, compared to their White counterparts (Williams et al., 2019). Furthermore, the life expectancy of non-Hispanic/Black Americans is four years lower than that of White Americans. Tai et al. (2021) demonstrated how the COVID-19 pandemic exemplified the enduring health disparities and the disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minority populations. Racism not only perpetuates health inequities but also hinders the nation and the scientific and medical communities by limiting access to a diverse range of talents, expertise, and perspectives. This deprivation impedes efforts to address racial and ethnic health disparities effectively. It is evident that racism poses a lethal threat to Black Americans, indigenous people, and individuals of color. Racism is a systemic problem that contributes to severe health issues like diabetes, stress, maternal mortality, hypertension, asthma, mental health conditions, heart disease, and premature death.

Racism is deeply embedded in federal and state policies and practices that have evolved over time to perpetuate and systematize racial discrimination (Yearby et al., 2022). These discriminatory systems limit individuals’ access to power, making it challenging for them to effect change within the systems they are bound by. Pervasive discrimination not only impacts day-to-day existence but also disempowers members of racial minority communities, depriving people of a voice and a sense of agency in their lives. To foster a healthier America for all, it is imperative to confront the systems and policies that have perpetuated generational injustice, giving rise to racial and ethnic health inequities. The head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Walensky (2023), summarized the agency’s commitment to leading efforts against racism as a public health threat.

Federal Structure, Divisions, Authorities, Services

In the previous section, discussions showed the basic timeline for the development of the current federal agencies charged with leading, supporting, promoting, and overseeing public health efforts. The existence of each agency is engrained in legislation and directed by the current administration under the purview of the President. Surveys of the population, policy development, standard setting, creation and enforcement of new laws and regulations, health and biomedical research, and the financing of health-related services are some of the public health functions which federal authorities execute (Chapman et al. 2013). Federal authorities also orchestrate and support efforts within states and globally. The scope of efforts of federal workers extends to identifying chemical hazards or toxins and coordinating clean-up efforts to ensure public safety.

Table 1

Organization of the Department of Health & Human Services

|

Secretary Deputy Secretary Chief of Staff |

|

|

Immediate Office of the Secretary

|

Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs (IEA) |

|

Office of the Secretary Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration (ASA) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Financial Resources (ASFR) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Legislation (ASL) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR)* Office of the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (ASPA) Office for Civil Rights (OCR) Departmental Appeals Board (DAB) Office of the General Counsel (OGC) Office of Global Affairs (OGA)* Office of Inspector General (OIG) Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals (OMHA) Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) HHS Chief Information Officer |

Operating Divisions Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Administration for Community Living (ACL) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)* Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR)* Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR)* Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)* Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Food and Drug Administration (FDA)* Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)* Indian Health Service (IHS)* National Institutes of Health (NIH)* Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)* |

*Components of the Public Health Service.

#Administratively-supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health.

Source: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/orgchart/index.html. Content created by Digital Communications Division (DCD). Content last reviewed August 17, 2023

As of 2023, the organizational chart of the Department of Health and Human Services was led by a Secretary, a presidential appointee. The Office of the Secretary oversees 12 operating divisions (see Table 1); nine of the divisions are parts of the public health service, and the remaining three manage human services.

Under the auspices of the Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs, there are 10 Regional Offices that directly serve state and local organizations. There are regional offices in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Kansas City, Denver, San Francisco, and Seattle. Each regional office is led by a regional director who is appointed by the President. Directors ensure the communications, contacts, activities and resources are available for state, local, and tribal partners to address the ever-changing needs of the population served through policies and programs administered by the Department of Health and Human Services.

States, Localities, and Territories

The administration of public health policies, regulations, and supports differs regionally by state, locality, and territory (https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/). The following discussions include overviews of two state systems and associated local public health systems: Vermont, Virginia, and Texas. The Marshall Islands, a member of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, is also included to demonstrate the reach of the federal government, the flexibility in the public health system, and the dissemination of services and supports to meet U.S. commitments and obligations.

Vermont: Blueprint for Health

In 2003, an initiative called the Blueprint for Health was launched in the state of Vermont by the governor (Jones et al., 2017). The purpose of the initiative was to control healthcare costs associated with chronic health conditions by developing a model. The success of the initiative led to legislative changes in 2007 which provided grant funding for participating localities and service providers. The Blueprint team provides training to stakeholder-partners and develops programs for improving well-being and health outcomes within communities. The programs are designed to intentionally address problems like opioid addiction and women’s health, and to develop community health teams, and educational workshops.

Based on a set of codes called the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home initiative, the development of patient-centered medical homes (PHMHs) was one of Vermont’s early initiatives that has been adopted by many states and localities across the United States (Sinaiko et al., 2017). Medical homes (situated in communities) constitute a combination of (a) patients’ voices in decision-making, (b) inclusion of all patients’ care needs, (c) synchronization of services across the healthcare system, (d) accessibility, and (e) commitment to measuring safety and quality of outcomes. The PHMHs are a systematic support network in which the care needs of the community are the central focus and is different from what occurs in traditional healthcare systems. This coordinated care approach provides whole-person support, improves outcomes, and controls costs.

The popularity of the PHMH model is due in part to its scalability; that is, the model is easy to replicate, is adaptable, and can be used locally, regionally, or statewide. The model includes performance measures and quality indicators. The effectiveness of the PHMH in Vermont got the attention and the support of national and private insurers, as well as self-insured businesses in the state. Backed by these insurers, performance-based incentives are now provided to support the utilization of healthcare resources and to increase quality in communities.

Mohlman et al. (2020) completed a report in which they evaluated the outcomes of, and lessons learned from the Integrated Community Care Management (ICCM) Learning Collaborative. The purpose of the ICCM was to streamline and improve services to vulnerable individuals who had complex needs (physical and mental health). Providers in regions and localities who integrated ICCM received access to coordination tools and training like how to conduct root-cause analyses and eco-mapping, software. Once a lead coordinator was identified, the goals of the ICCM could be implemented; the ICCM goals included (a) coordinating providers and reducing the fragmentation of care, (b) improving access to appropriate, timely, and quality care, (c) eliminating overlapping or unnecessary services where possible. By the end of year two of the project, all but two of Vermont’s hospital systems used ICCM. The positive outcomes of the project were a marked reduction in the use of emergency rooms and increased utilization of managed care that met the complex needs of the patients served. Across the participating hospital systems, costs remained unchanged. As Mohlman et al. evaluated the project, they noted indicators of trends that might require additional exploration and research.

Virginia Department of Health – Healthy People in Healthy Communities

The mission of the Virginia Department of Health is “to protect the health and promote the wellbeing of all people in Virginia,” (https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/). The institution has the lofty vision of being the healthiest state in the United States. Health department activities are guided by the Board of Health; a 15-member group who convene quarterly and report annually to the state’s governor. The board members’ responsibilities are codified in state law and include:

· The formulation and review of programs, health and laboratory services, and clinics at regional, district and local levels.

· Set standards for determination of benefits to be paid by the state.

· Establish and fund health education and worksite programs.

· Develop regulations based on the law.

· Make emergency regulations or mandates to protect the health of the state’s population.

· Ongoing research.

· Other functions and responsibilities defined by the Code of Virginia. See the Code of Virginia for full text at https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title32.1/

Virginia’s Department of Health maintains public records of births, immunizations, marriages, and death. The department administers programs like Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) and Child & Adult Care Food Program (CACFP). Public safety services include information on disease testing, environmental testing for chemicals like radon, how to find places to get safety checks for seat belts or infant car seats and finding licensed health service providers.

In the Commonwealth of Virginia, services are delivered at the local level by town, city, and county governments. The city of Chesapeake in the southeast corner of the state provides information and services for emergency preparedness and mosquito control (https://www.cityofchesapeake.net/Home.html). This city is less than 15 feet above sea level, the climate is humid most of the year, and the area is prone to hurricanes and flooding, so there is a need for the maintenance of evacuation routes and controlling disease-carrying insects. Chesapeake’s Parks, Recreation, and Tourism division maintains local parks and trails, supports local youth sports and activities like kayaking, and offers classes to the public. Classes are available for all age groups and include art, dance, boxing, beginner’s sewing, and tennis.

Carroll County, Virginia is located in the south-central area of the state at the base of the Blueridge mountains (https://carrollcountyva.gov/). This is a rural community and support services differ from those offered in urban areas like the City of Chesapeake. For example, the county offers a public emergency alert program for receiving notifications of severe weather, evacuations, and missing persons. The parks and recreation division in the county supports both adult and youth sports leagues supported by volunteer referees and umpires. The county relies on volunteers to provide ambulance and fire services, and to facilitate elections. The county provides a farmer’s market and a cannery where people can use the facilities to preserve foods harvested during the growing season.

The centuries-long history of public health in Virginia is rich with accomplishments and firsts. Visit the state’s website here: https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/commissioner/history-of-public-health/. Records show the first law on sanitation was passed in 1610. In 1780, the first board of health was established in the city of Petersburg. Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the Virginia Health Department was the first state to launch a digital application for citizens to monitor the severity of outbreaks in their local areas. Public Health 3.0 is an initiative to create a collaborative ecosystem of public health services to meet the future needs of Virginians

Texas: A Healthy Texas

The Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) are similar in most respects to other states (https://www.dshs.texas.gov/). There are more than 29 million people in Texas (https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/), and more than a third of them speak a language other than English (85% speak Spanish). All printed materials produced by DSHS are in Spanish and English. The latest U.S. Census data showed a per capita income of $31,277 and a 13.4% poverty rate for the state. Control of the health and human services is centralized in Austin, Texas, the state’s capital city.

The Consumer Protection Division of the DSHS uses campaigns to promote and improve public health. Campaigns include emergency preparedness, immunizations, substance abuse, food safety, radiation control, and more. In 2005, Texas legislators passed State Bill 316 (https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/). This special interest bill was developed to help reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality rates (https://www.dshs.texas.gov/). State Bill 316 requires healthcare providers who treat pregnant women and infants to educate all caregivers (parents, grandparents, foster parents) on specific topics. Topics include newborn screening and immunizations, postpartum depression, and shaken baby syndrome. Locally, services are administered at the district level. For example, the city of San Antonio is in Bexar County which is served by the Metropolitan Health District (https://www.sanantonio.gov/Health/).

Guided by federal and state laws, city code, and county resolution, this organization is responsible for the administration of programs like WIC, health code and ordinance enforcement, health education, and environmental monitoring. The programs supporting the physical wellbeing of the population are managed by the city’s government through San Antonio Parks and Recreation. The city partners with private industry, conservationists, and philanthropists to maintain parks, trails, and golf courses for public use.

Republic of the Marshall Islands

Under a United Nations compact created in 1947, the United States was given administrative authority over the Trust Territory, a group of Pacific Island states. The compact was amended in 2004 and has no termination date. The Trust Territory includes the Republic of the Marshall Islands; The U.S. obligations to the states in the Trust Territory include defense and security, a visa program for residents who want to live, work, or learn in the United States. Citizens of the Marshall Islands may also serve in the U.S. armed forces.

The U.S. government invests $80 million annually in the Marshall Islands. These funds support six sectors including health and education (https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-marshall-islands/). Funding received from the U.S. government supports healthcare services on 4 atolls affected by nuclear testing in the 1940s (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021). Health services are provided through hospitals and a network of 59 clinics located across the islands. The unique services provided by the Ministry of Health and Human Services (MOHHS) include a Green Prescription program. In this program, doctors and health practitioners actively engage with the population to promote healthy eating, physical activity, and chronic disease prevention.

Public Health Goals

“… the core functions of public health agencies at all levels of government are assessment, policy development, and assurance,” The Future of Public Health (1981)

The MOHHS partners globally with countries like Australia and Taiwan to bring specialized healthcare services to citizens; visit About MOHHS at https://rmihealth.org/about-mohhs/ongoing-projects to learn about global activities. In 2023, for example, Taiwanese dermatologists provided evaluation and treatment for a variety of skin disorders and lesions. The MOHHS coordinated tuberculosis screenings at the Aur Atoll. The Republic of the Marshall Islands is part of the Western Pacific region of the World Health Organization (WHO); partnership with the WHO expands access to additional public health resources like vaccinations, a healthcare workforce, and climate change information.

Review of the U.S. Public Health System

The State of Vermont, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the State of Texas, and the Commonwealth of Virginia are examples of how federal law and funding are used to deliver public health services to different populations. Jarvis et al. (2020) acknowledged the complexity of public health by defining it as an intricate set of laws, values, organizations, social systems, and administrators with the singular goal of improving the health of a population. Quoting Acheson’s (1988) description, writers at the World Health Organization (WHO) defined public health as the sum of “the art and science of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts of society,” (WHO, para. 1). This broad definition can be further refined to include all contributors to the system or network that constitutes public health service within a given community.

There are clear distinctions between public health and medicine. At the center of the practice of medicine are the science, diagnostics, and treatment of diseases. Advances in medical science have created areas of practice specialization such as pediatrics, obstetrics, oncology, and geriatrics. Practitioners of medicine follow an ethos based in social responsibility, beneficence, gratitude, confidentiality, and humility to preserve human life and to do no harm (India & Radhika, 2019). Dating back to 400 B.C., the Hippocratic Oath was the gold standard that physicians and medical auxiliaries followed; however, current practitioners must also consider bioethics. Medical practitioners treat individual patients and teach people how to take care of themselves whereas, public health professionals work to prevent of the spread of communicable diseases, managing public health hazards, and responding to natural or man-made disasters.

Public health professionals have to focus on the needs of the communities they serve. Observing the examples used in this text, the differing community needs become clear. In the Marshall Islands, for example, there is greater focus on nutrition and the development of healthy behaviors; morbidity and mortality rates have been linked to the indigenous diet and culture. Environmental pests and weather-related emergencies pose greater threats in Virginia. Infant morbidity and mortality are a primary concern in Texas that warrants leveraging of infrastructure and informational campaigns to educate the public and care pre- and post-natal care for families. Whether promoting health through education, preparing for emergencies, or preventing illness, a core value of all public health is reducing disparities related to access and health outcomes while increasing health care equity (CDC Foundation, 2022). Federal funding supports research and science, data collection, environmental monitoring, planning, and informed decision-making to increase health outcomes and decrease risks for everyone.

Wellness Defined: The Prevention Approach

To define wellness, it is important to also define health. The World Health Organization (1948) defines health as, “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” and wellness as “the optimal state of health of individuals and groups,” expressed as “a positive approach to living.” This means that health is the outcome of interest and goal while wellness includes the process needed to achieve health.

Challenges to Achieving Wellness

From achieving the recommended physical activity levels, stress reduction, increased nutrition, maintaining well visits, to acquiring recommended sleep, it is important to recognize that challenges in achieving wellness include deeply rooted, complex social context and culture to support health, and lack of access to a prevention approach (American Public Health Association, 2023; Centers for Prevention and Disease Control, 2023; World Health Organization, 2023). Many populations are in need of clean drinking water, clean air, healthy food, safety, and access to health care (World Health Organization, 2023).

In addition to cultural challenges, behavior change is complex, and compliance to wellness habits and programs is poor as several underlying factors have yet to be addressed (Reif et al., 2020; World Health Organization 2023). Therefore, a culture that enables and empowers community members, students, employees, or patients to make wellness a part of their routine is needed. From providing farmers markets and protected walking and bicycling paths to encouraging walk breaks to offering cycling desks to conducting meetings while being active, making wellness a part of community planning, curriculum, onboarding, educational trainings, and building awareness of the multidimensional value of wellness may encourage progress.

Wellness Dimensions

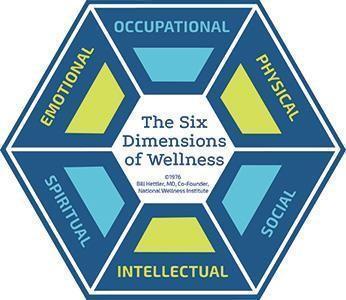

Six dimensions of wellness are defined by the National Wellness Institute (2021): emotional, occupational, physical, social, intellectual, and spiritual (Figure 1). Each of these dimensions of wellness needs to be supported at the policy, community, environmental, organizational and individual levels – and these levels connect. The value of wellness needs to be communicated and upheld to encourage investment in wellness at the individual level as well as the institution or organization levels all the way to the global level.

Figure 1

National Wellness Institute’s six dimensions of wellness

There are traditional biometrics (body composition, blood glucose, blood pressure etc.) that can be used to measure wellness as well as risk reduction (focusing on reducing risk of type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure rather than weight loss) based on changes in biometric numbers. Validated instruments including self-report of behavior change including physical activity, stress reduction, nutrition, well visits, health related quality of life, and sleep should also be included and resulting risk reduction programs should be provided to communities, students, employees, or patients.

The economic benefit of wellness is a helpful measure to communicate the value of wellness. This includes, but is not limited to, reduced health care spend/utilization, reduced sick days, increased productivity, and morale. Therefore, components of many wellness programs include health-risk assessments, screenings for high blood pressure and cholesterol, nutrition counseling, physical activity promotion, websites for health information and activity tracking, and changes in the community, school, or work environment (Anderson, 2009).

There is no one size fits all that enables one person to adjust their personal mental and physical well-being and reach their highest level of wellness and resulting health. In addition, there is no specific routine that enables wellness changes over time. Need for sleep, physical activity and nature breaks, nutrition, mental stimulation, and other stress reduction strategies need to be flexible around changes in childcare, health, or say, a pandemic. Identifying barriers to wellness activities or productivity and work are important to examine. Trainings and resources on meal prepping, planned snacks, physical activity and nature breaks are shown to be helpful. Flexibility not only allows for engagement in wellness activities, but it is also shown to reduce stress and help achieve better health.

Wellness and Prevention Role and Relationship (integration) Within the Healthcare System

The County Health Rankings (2023) report that only 20 percent of total health can be attributed to clinical care. Wellness initiatives, socioeconomic and environmental factors make up the other 80 percent. Hospitals are increasingly looking at ways to get involved in these other factors – often action is taken when addressed in policies and/or law such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act PPACA – to better serve their patients and to stay financially afloat (Roadmaps to Health, 2023). This means hospitals realize the policy and or law requirements and sometimes monetary benefits of evolving from an individual care system to a societal perspective. However, surveillance framework and measures to determine impact are still being developed to prove just how much the return on investment might be (Kruk et al., 2018).

Wellness Impact on Non-communicable Diseases

Non-communicable disease (NCD’s), or chronic diseases, include those that are not passed from person to person. These diseases tend to present for a long duration, often for the rest of a person’s lifetime, and onset as a result of genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioral factors. NCD’s include heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and chronic kidney disease and are the leading causes of poor health, long-term disability, and death in the United States (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2018; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). NCD’s tend to reduce quality of life as working can be difficult with rates of absenteeism are higher and income is often lower among people who have a chronic disease compared with people who do not have one (World Health Organization, 2024). Additionally, functional limitations often occur and result in depression – which can reduce a patient’s ability to cope with pain and worsen the clinical course of disease (Turner & Kelly, 2000). NCDs disproportionately affect people in low- and middle-income countries in which more than three quarters of global NCD deaths, or 31.4 million, occur (WHO, 2023).

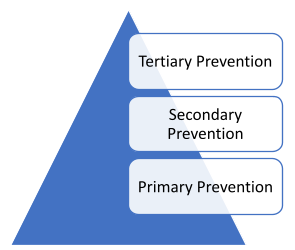

Clinical preventive strategies are available for many NCD’s. These strategies include intervening, often with wellness strategies, before disease occurs (primary prevention), detecting and treating or intervening with disease at an early stage (secondary prevention), and managing disease to slow or stop its progression (tertiary prevention). Lifestyle changes including physical activity, nutrition, sleep, and stress management, can substantially reduce the incidence of chronic disease altogether – or at least delay the onset of the disease – resulting in improved quality of life (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2009).

Interventions to reduce and delay the onset of NCD’s not only improve the persons’ quality of life, but the burden to both patients and the health care system as 60% of adult Americans have at least one chronic disease or condition, and 40% have multiple diseases (Centers for Disease Control and Presentation, 2022). One-third of all deaths in this country are attributable to heart disease or stroke and each year, more than 1.7 million people receive a diagnosis of cancer (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2018). During the past several decades, the prevalence of diabetes increased substantially to over 29 million Americans with diabetes and another 86 million adults with prediabetes in 2015 which often results in developing type 2 diabetes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Diabetes increases the risk of developing other chronic diseases, including heart disease, stroke, and hypertension, and is the leading cause of end-stage renal failure (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018).

Chronic diseases are the leading drivers of health care costs in the United States (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2018). Total direct costs for health care treatment of chronic diseases were more than $1 trillion, with diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and osteoarthritis being the most expensive (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2018). If lost economic productivity is also considered, the total cost of chronic diseases increases to $3.7 trillion – one-fifth of the entire US economy (Waters & Graf, 2018; Asay et al, 2018). These costs are expected to increase as the population ages. Projections include more than 80 million people in the United States will have at least three chronic diseases by 2030 (Waters & Graf, 2018).

Wellness Impact on Communicable Diseases

Wellness – including Physical activity (PA) – can limit the harms to human health and well-being due to infectious disease (Sallis & Pratt, 2020). This is due to the fact that active muscles produce chemicals that improve immune functioning, which in turn reduces the extent of infections, and decreases inflammation. This is socially helpful during the COVID-19 pandemic as these are the main causes of the lung damage from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. PA is a powerful preventive and therapeutic intervention for the most common pre-existing chronic conditions that increase risk of severe COVID-19 infections and mortality (Powell et al., 2018, Jordan et al., 2020). PA also enhances the efficacy of vaccines (Pascoe et al., 2014). Worldwide, about 23% of men and 32% of women are at risk for the underlying conditions of COVID-19, severe COVID-19 infections, and stress-related psychological symptoms, because they do not meet PA guidelines, based on self-report measures (Sallis et al, 2020).

Wellness Through the Lifespan: Child Health, Younger Adults, Older Adults

Public health continually evolves to identify and understand the shifting health needs of through the lifespan while considering social, economic, and demographic implications. Public health policies, programs, and practices must be incorporated to consider these needs within health care delivery systems to promote wellness for all ages and therefore provide comprehensive health care. Ensuring the health and wellness of children across diverse communities is a focus of the US public health agenda. For over a decade, there continues to be a focus to understanding pre-, peri-, and postnatal factors associated with differences in childhood wellness (Weden et al, 2012) as well as physical environment factors that facilitate daily wellness such as physical activity (Mori et al., 2012). Wellness efforts require a multifaceted approach. School and community-based efforts much provide a culture that educates youth and enables healthy choices while providing healthy environments includes healthy food options, green space physical activity space, and support. Family and home environments must be provided with support based on economic and psychosocial burdens increase stressful parenting and reduce mental health and well-being of parents and children (Yu & Singh, 2018). Differences in environments—from the biological to the societal—contribute to inequities in patterns of exposure and health outcomes.

Among adults, public health research and prevention efforts have historically focused on curtailing individual-level behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol use, sexual risk behaviors, unhealthy dietary habits, lack of physical exercise). However, there has been a notable shift in the past decade toward clarifying the complex roles that social, political, and economic inequalities play in shaping the health of adults and their families within and across societies. There are income inequalities and health in the United States that calls for a policy discussion on reducing health disparities requiring attention to broader social conditions, and not just health insurance and health care (Martinson, 2012).

Finally, this issue presents a picture of the complexities and challenges the public health community faces with the aging of our society. Disability trends among older US adults indicate that, after accounting for the effects of aging and for period effects that help tap changes in sociocultural, economic, technological, and environmental factors successive cohorts of older adults are becoming more disabled over time (Lin et al., 2012). Policies meant to enhance the social and physical well-being of older adults may have unintended consequences, which also require careful monitoring and prevention programming such as public transportation (Coronini-Cronberg et al., 2012) and fall prevention (Kapadia, 2012; Kelsey et al., 2012).

Communication: Brief History

An exchange of information using a sender and receiver is a basic way to describe communication. The term communication derived from the Latin word communicare which means to share or make common (Weekley, 1967). An effective exchange is required to understand the message through perception, interpretation, and delivery. Public health communication is “the study and use of communication strategies to inform and influence individual and community decisions that affect health” (USDHHS, 2015a, para. 1). Public health efforts to reach the public will continue to advance through scientific discovery and strategic dissemination of reliable health information. However, public health organizations must seize the opportunity within the media sphere to share information bidirectionally, update recommendations in a timely manner, but also analyze social media traffic and rapidly detect and counter emerging myths, rumors, theories of conspiracies, or simply misunderstood concepts (Khan et al., 2019). For public health professionals, refuting conspiracies and misconceptions is critical in guiding public decisions about health risk prevention, health promotion behaviors, identification and treatment of health disorders, and strategies for living with health hazards (Kreps et al., 2017).

In the mid-1800s, contemporary health pioneers Edwin Chadwick of the United Kingdom and Lemuel Shattuck of the United States published reports that revealed high death rates in metropolitan areas and postulated a link to a lack of sufficient sanitary conditions. In his report, Shattuck emphasized “ignorance,” whereas Chadwick identified “uneducated minds” as an issue that needed to be addressed. This was a watershed moment in public health because educating the public through communication, prevention dissemination, and promotion was the key to battling disease and minimizing sick days and lost workdays (Salmon & Poorisat, 2020). Individual sources such as health care providers, health care professionals, reading materials, instructors, and worldwide platforms such as social media expanded communication beyond mass transmission over time. Fenton (1910) postulated a link between news content and behavior in one of the earliest studies on media effects. Because communication campaigns had switched to mass media during the twentieth century, this discovery was noteworthy.

Health Communication Strategies

Public health experts use health communication as an effective strategy to reach the target audience through promotion and intervention efforts. Professionals can communicate through written or verbal strategies to address health issues, allowing them to accomplish the aims and objectives of health promotion initiatives. Information is disseminated by mass media, print materials, electronic formats, and social media. These ways of raising awareness enable the target audience to focus on altering their behavior, environment, and building a change culture. Effective healthcare communication methods have a tendency to reach a specific or broad audience, thereby increasing awareness and encouraging interventions. Effective communication tactics can also be used to persuade, motivate, educate, advocate, and clear up misunderstandings about public health issues. Therefore, mass communications, whether private or public, influence population health by shaping discourse about exposure risk and disease, influencing the adoption (or non-adoption) of health-promoting social policies, connecting people to health services, and providing education and motivation that influence behaviors (Schillinger et al., 2020). Visit the Rural Health Information Hub at (https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/health-promotion/2/strategies/health-communication) to explore health communication strategies and Rural Health Promotion and the Disease Prevention Toolkit.

Communication Platforms and Channels

With the increased desire for quick communication and succinct information, a solid digital strategy based on best practices, consistency, and awareness of your target audience is critical for increasing engagement and reaching new audiences (Gatewood et al., 2020). There are several methods of communication. According to the World Health Organization (2024), when public health professionals aim to promote and improve health, this occurs using a variety of channels, delivering resources, and trustworthy routes. Communicators should examine the audience’s preferences and access to various channels in order to choose the most effective communications paths. Traditional communication channels include print (e.g., newspaper, magazines); broadcast (e.g., television, radio); outdoor (e.g., signage, billboards); personal (e.g., word of mouth); or items (e.g., T-shirts) (Thackeray & Neiger, 2009). In terms of the quantity of individuals they reach, these channels follow a tiered structure. The intrapersonal channel normally reaches the fewest people, whereas the mass media channel reaches the most people.

However, public health practitioners can now use social media to inform audiences about health issues, improve communication during public health emergencies or outbreaks, and respond to public reporting of a specific public health issue at a low cost (Gatewood et al., 2020). Currently, 2.82 billion individuals use this technological breakthrough on a regular basis, and they have access to tens of thousands of health-related social media websites that are currently available to the public (Stellefson et al., 2020). Today, many public health agencies and organizations are reaping the benefits of professional blogging as part of their communication strategies. Blogs, as a media platform, have enabled organizations like Public Health-Seattle & King County (Public Health Insider Blog), Big Cities Health Coalition (Front Lines Blog), National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO Voice), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to share reliable, evidence-based information with both public and professional audiences (Gatewood et al., 2020).

Despite the fact that these new platforms (such as social media and blogging) appear to be useful because of their digital approach to reaching a larger audience, they confront challenges owing to the nature of social media. The problem is that it is challenging to keep track of what’s disseminated. Users can utilize the open platform to not only receive health information, but also to interact with it, which may or may not be correct (Stellefson et al., 2020). Misinformation on social media may obstruct the development of an effective response to public health challenges in general. In the past, traditional news media and interpersonal channels were the primary sources of information during a public health crisis, but more recent studies have indicated that online news and social media are now the preferred routes during a crisis. This could be a problem when most people rely on more than one source when following a crisis, such as the Coronavirus (COVID-19), climate change, or mental health. An example of a crisis gone awry was the MERS outbreak in South Korea. In 2015, MERS was confined to the Arabian Peninsula, and within the same year spread to South Korea, where cases wildly escalated. Korean officials warned the public that the infection would not spread unless directly exposed in an attempt to alleviate fears. On the contrary, the news reported an upsurge of infected cases within a few days, and the topic became national interest. It was then Koreans sought information (i.e., hospital names, infected location of care) on avoiding exposure to the infected, which was withheld. The withholding of this information forced people to seek answers among themselves, word of mouth, and the information of the hospitals and infected patients surfaced on social media. It was then social media and interpersonal channels continued as the main information channels for most Koreans (Jang & Baek, 2019). When hazards occur in the environment, ambiguity tends to rise, leading to a greater reliance on the media. When the media gathers and distributes information that helps clarify the current situation and promotes behavior to avoid threats, the uncertainty in these situations can be resolved (Jang & Baek, 2019).

Artificial Intelligence Impact on Public Health Communication

Public health relies on communication to address prevention, promotion, and quality of life. In some cases, communication is deemed just as important as operations, and evolutionary changes involving technological advances have significantly improved the accuracy of customizing health promotion and disease prevention as well as rehabilitation and disease management (Giansanti, 2022). Although there are various definitions of artificial intelligence (AI), one must consider the applications. Jungwirth and Haluza (2023) define artificial intelligence (AI) as a software program that can simulate a context-sensitive response or a conversation with a human user in natural language through messaging services, websites, or mobile applications. Although still in its infancy in some industries and fields, the impact of AI on public health communication has been instrumental in benefitting health education and promotion with accessible, cost-efficient, and interactive solutions (Jungwirth & Haluza, 2023). Additional benefits include:

- Self-management of chronic diseases (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, and asthma)

- Access remote and automated health services (i.e., screenings, diagnoses, therapy).

- Monitor and track health data, symptoms, and treatments.

- Provide emotional support for mental health issues.

The Digital Transformation Toolkit knowledge capsule by the Pan American Health Organization (2021) further increases awareness, principles, and subfields that benefit public health in various forms of communication. These components and subfields include:

- Machine learning (the process of applying training data to a “learning algorithm).

- Cognitive search (use of AI solutions to incorporate and understand digital content).

- Natural language processing (ability to read, understand, and derive meaning).

- Virtual agents (chatbots) are “conversational agents” (mimics of written or spoken human speech).

Deep learning (can identify diseases based on imaging and predict health status from electronic health records). Through this form of communication and adherence, users are able to be proactive in their health by making more informed health decisions (Jungwirth& Haluza, 2019). By using AI to monitor health conditions, a chatbot is one interface that assists in interacting with patients suffering from a condition. It can reduce readmissions by guiding patients to stay on track and early intervention if signs of worsening a condition occur. On the contrary, research surrounding public health has described AI as being slow in communicating and generating automated early warnings for epidemics. In history, there have been epidemics that have proliferated, leaving minimal time for proper communication and notifications. One instance of this is the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) pandemic in Wuhan, China, which may have begun with a single case and quickly grew to a few instances in a short period (MacIntyre et al., 2023). Nevertheless, AI’s impact on public health communication is more central than ever, and, due to its capabilities, should be used at an operational level in the everyday practice of public health compared with the use of AI in clinical medicine (MacIntyre et al., 2023).

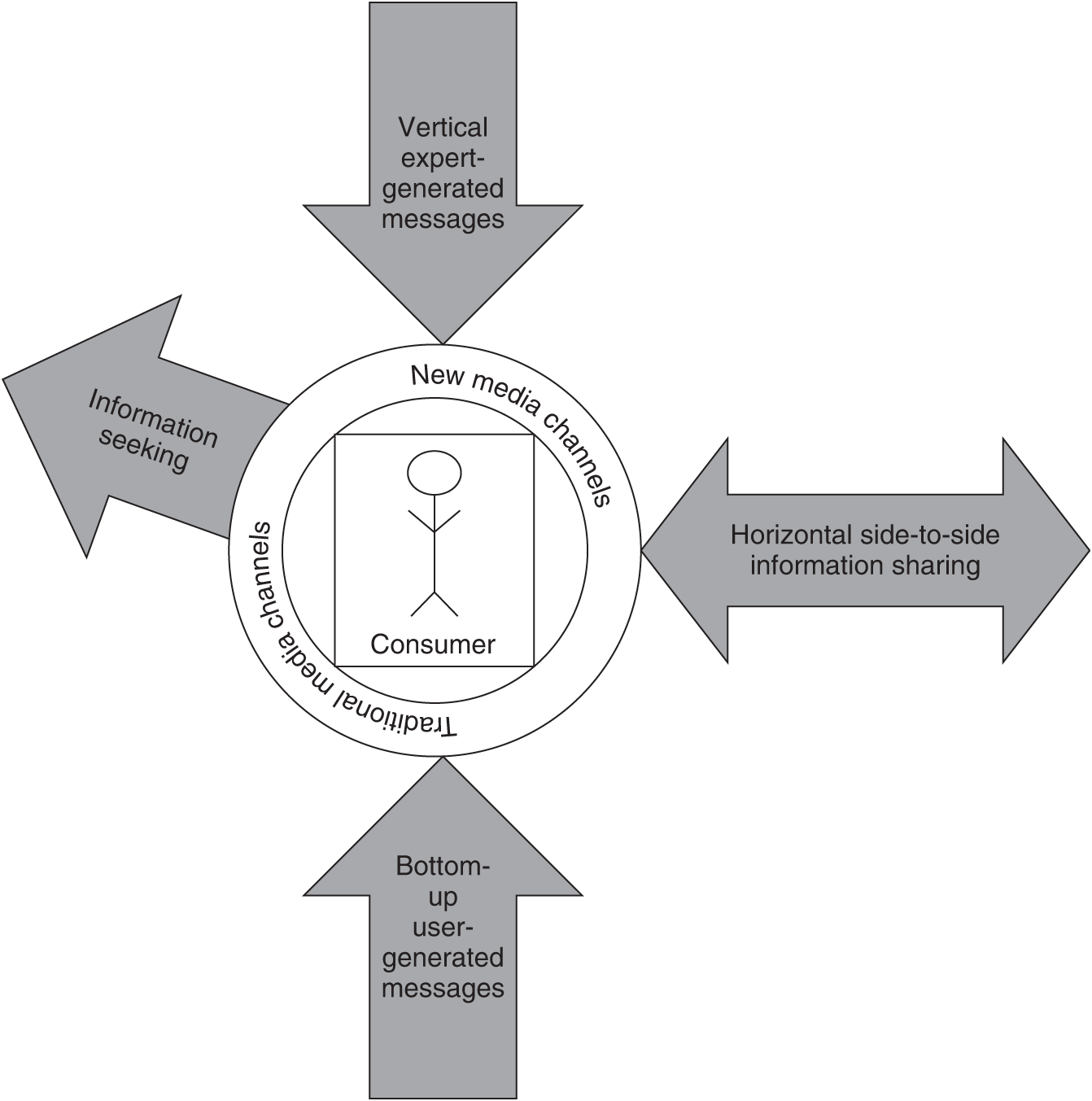

Multidirectional Communication Model (MDC)

The multidirectional communication model (MDC) has emerged as a result of new technology (Thackeray & Neiger, 2009). The MDC model is described as a combination of top-down (vertical) messages from the sender, bottom-up communications from consumers, horizontal (side-to-side) messages shared by consumers, and consumers seeking information (Figure 1). As a result, in the MDC model, customers not only receive but also actively seek for, generate, and exchange information (Thackeray & Neiger, 2009). This type of communication, compared to the traditional way of communication, a sender sends a message through a channel to the receiver, has evolved in the last 25 years, and this alteration is associated with the ever-changing of the internet in particular social media and how consumers consume traditional media (Thackeray & Neiger, 2009). By altering the type and speed of engagement, social media has facilitated exchanges between individuals and health organizations which could lead to messages going viral.

An example of the MDC is the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may develop a campaign for those who are diabetic and obese to eat healthy and be physically active. The promotional strategy includes a 40 second commercial on YouTube channel Life Well and posters in healthcare providers’ offices. In addition, communication occurs from the bottom-up or by the consumer generating information. Examples include nutritional advertisements created for people with diabetes who are obese as part of the campaign, which is then posted on YouTube. Communication also occurs horizontally. This type of communication occurs when information or an experience is shared between consumers without the influence of a gatekeeper. An example is a diabetic individual sharing information on Facebook or Instagram on how to deal with diabetes, proper nutrition, and physical activity. Finally, in this model, consumers actively seek information. For example, a person with diabetes may search the internet to learn more about diabetes and physical activity.

Figure 1

Multidirectional Communication Model adapted from James F. McKenzie, Brad L. Neiger, Rosemary Thackeray, 2016

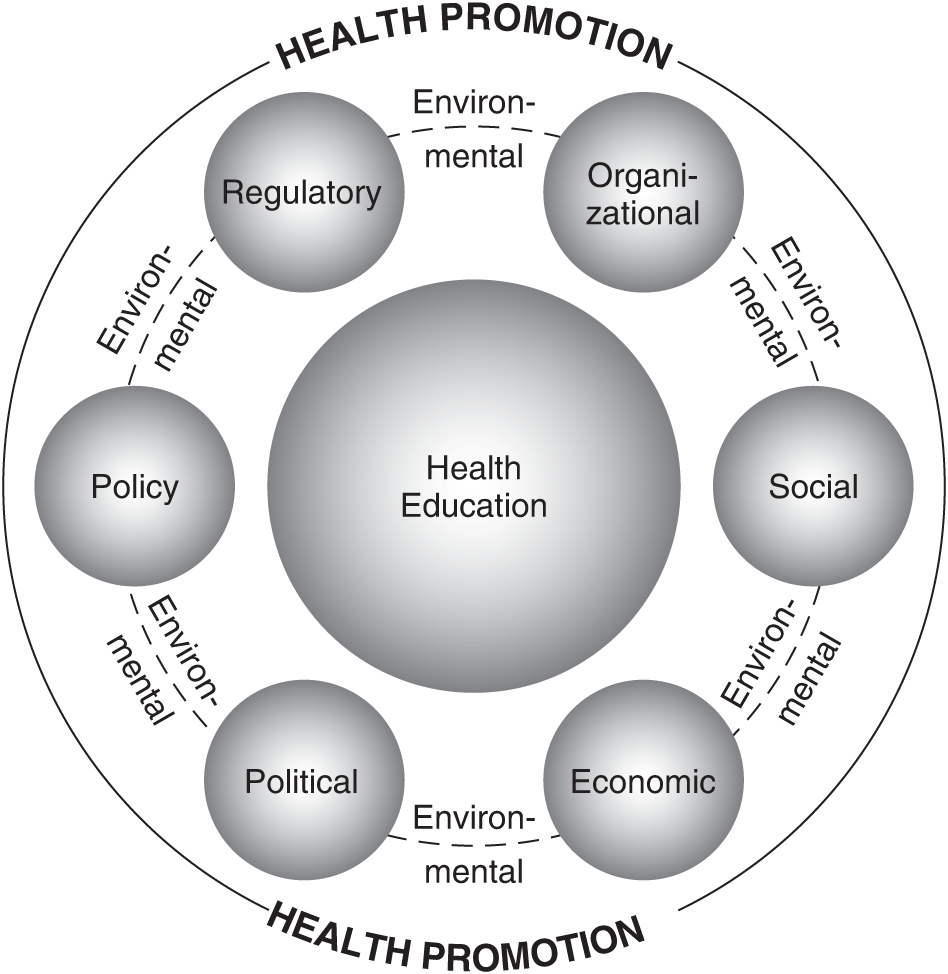

Health Promotion and Education

Health education and health promotion are two terms that are used interchangeably. Health promotion is focused on the social system, whereas health education is aimed at the individual (Figure 2) displays the terms of promotion and education in the context of the environment. The World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health promotion is the most well-known, as it is incorporated in the Ottawa Charter, which was adopted at the First International Conference on Health Promotion (Ottawa 1986). Health promotion, according to this definition, is “a process that allows each individual to improve their impact on their health in terms of improving and maintaining it” (Wrona-Wolny, 2018). People must have the appropriate skills to participate in promotional efforts and make changes in their lifestyles and environment, which can be achieved through health education campaigns (Wrona-Wolny, 2018). Furthermore, health promotion is incomplete without health education. Both notions refer to activities aimed at assisting people in gaining control over the variables that may affect their health and creating a healthy environment. Although the two concepts are distinct, there is a connection between health education and health promotion, specifically human health, which is stressed as the common objective of these activities (Wrona-Wolny, 2018). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022) is a staple of health promotion for children and adolescents. Visit the site (https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/children-health.htm) to view its approach when working with parents, educational facilities, schools, health systems, and communities to keep children healthy. Enabling people to have more control over their health and its determinants is at the heart of health promotion, and it’s more important than ever because a variety of public health challenges represent a threat to marginalized people on numerous levels. For example, Individual behavior modification and illness management are prioritized at the downstream level. In contrast, interventions influencing organizations and communities are prioritized at the midstream level and informing policy affecting the population is prioritized at the upstream level (Van den Broucke, 2020). It is critical for health promoters to remember that the audience not only receives but also comprehends, accepts, and applies the information. According to health literacy research, more than a third of the world’s population has difficulty locating, comprehending, assessing, and using information necessary to manage their health (Van den Broucke, 2020). Providing understandable information; providing transparent information with the caveat that time and research information may change; presenting information without fear of correcting earlier promotions; avoiding blaming and strengthening the individual’s well-informed responsibility are all recommendations for improving health literacy.

Figure 2

Health Promotion and Health Education adapted from James F. McKenzie, Brad L. Neiger, Rosemary Thackeray, 2016

Prevention Dissemination

Public health’s efforts to reach its target audience rely heavily on information dissemination. Access to and effective use of relevant, accurate, and timely health information is vital for directing important health-related decisions that consumers and providers must make across the continuum of care in order to improve health and well-being. Researchers are working to understand how effective the dissemination of information is to marginalized populations. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) launched the repeated measure Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) research program in 2003 to investigate the complex patterns and influences of health information dissemination in the United States (Kreps et al., 2017). HINTS monitor public access to and usage of pertinent health data in the United States, as well as public preferences for obtaining this data (Kreps et al., 2017). This measurement is taken once a year and has proven to be a useful tool for public health officials to identify public health gaps and direct focused health education intervention programs, which are required to improve informed health decision-making. Most significantly, HINTS is a valuable resource for research on public access to and use of health information in the past, present, and future (Kreps et al., 2017).

The characteristics of the audience are critical in choosing a dissemination strategy when it comes to sharing information. Using marketing tactics, professionals can assist in the design of effective health communication campaigns. In social marketing, the idea is simple: customizing a product and promotion plan to the characteristics of a desired group increases the likelihood of success (Brownson et al., 2018). For example, public health practitioners and policymakers are two of the most essential audiences for dissemination; they share some traits but also differ significantly. When considering audiences for dissemination, framing is also crucial. Individuals can interpret the same data in a variety of ways, based on their mental model of information perception. Weighing the benefits and dangers is a good way to frame the issue for public health audiences. Risks and advantages are frequently perceived in terms of psychological, emotional, moral, or political frames, rather than scientific terms (Brownson et al., 2018). The goal of a good dissemination plan is to persuade people that the advantages (for example, lives saved by a new policy) outweigh the risks (for example, economic or opportunity costs) (Brownson et al., 2018).

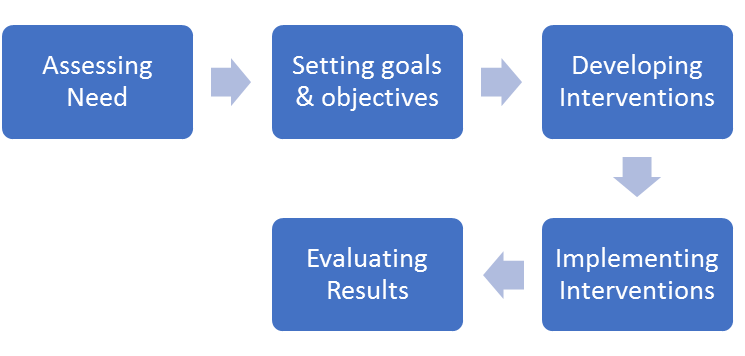

Community Involvement in Public Health

A community is defined as “a group of people who share shared features such as geography, interests, experiences, concerns, or ideals” (Joint Committee on Terminology, 2012, p. S15). International health guidelines already emphasize the need for community participation. In order to plan, produce, execute, and evaluate the best possible health promotion and healthcare services, the coproduction of health relies heavily on incorporating the thoughts and ideas of numerous communities (Marston et al., 2020). As a result, with the support of the community, public health specialists may develop unique, tailored solutions that serve the whole spectrum of requirements of our various populations. Over the last few decades, community engagement has grown in importance, and it is now recognized as a crucial strategy for maximizing community potential in health development.

Community engagement has been widely used by health interventionists to engage communities in health promotion, research, and policymaking to address issues such as obesity, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, smoking cessation, and mental illness. It is defined as a process of working collaboratively with groups of people who are affiliated by geographic proximity, special interests, or similar situations with respect to issues affecting their well-being (Cyril et al., 2015). As simple as it may appear to involve the community, it can be difficult to do, and high-quality coproduction of health takes time. To enable long-term and inclusive engagement, meaningful relationships between communities and providers should be cultivated since communities are involved in decision-making throughout the research process, from proposing research questions to distributing research findings. However, managing participatory spaces necessitates sensitivity and caution in order to recognize and harness the various types of knowledge and experiences given by various communities and individuals, as well as avoiding repeating societal structures that may cause damages such as stigma (Marston et al., 2020).

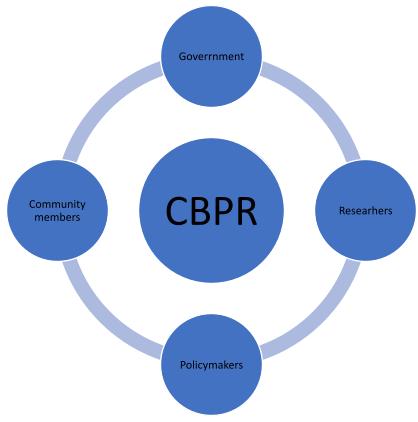

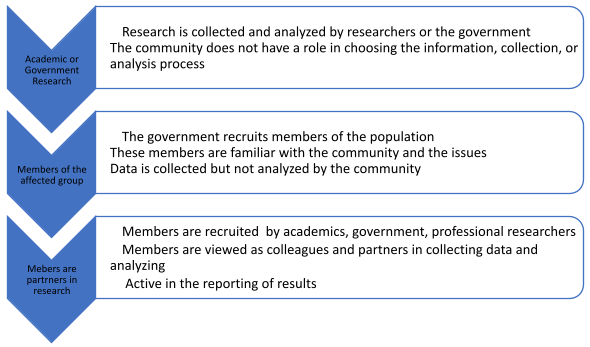

Community Based Participatory Research (CBP)

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a type of research that involves a collective, reflective, and systematic inquiry in which researchers and community stakeholders participate as equal partners in all stages of the research process with the goal of educating, improving practice, or effecting social change (Tremblay et al., 2018) (Figure 3). Through this type of research, relationships between the researcher and the community, particularly underprivileged communities, can be improved. This allows the power to be evenly distributed between the researcher and community because it encourages the formation of respectful connections between these groups and the sharing of power over individual and group health and social circumstances. The focus of CBPR is on a participatory method to identify social determinants of health and explain discrepancies in health-related risk factors by bringing stakeholders together to identify needs, challenges, and assets in marginalized areas. As a result, this collaboration transforms public health efforts by effectively developing, implementing, and evaluating interventions and policies. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (2024) has a CBPR program that supports collaborative interventions and works with a wide array of conditions and diseases, including cancer, diabetes, heart disease, HIV/AIDS, and others. Since its inception in 2005, the entity has funded 25 CBPR planning grants. In 2008, it was awarded 40 grants for Phase II. These grants were dispersed among 25 states.

CBPR could be utilized for a variety of goals, including the evaluation and long-term change for people most impacted by a community issue. Conducting and analyzing the problem with the help of multiple stakeholders gives public health promoters a higher possibility of coming up with solutions. Furthermore, because the information comes from the “voice” of the community, community buy-in helps with gathering information needed for policy changes. CBPR is frequently used in academia and implemented and embedded in government research where information is sought, data is collected, and analysis is performed. This participation could take place at many levels beginning with the academics and government collecting and analyzing the data, or academics and the government recruiting the group members of an affected group to collect data without analyzing it, or members of an affected group become partners in the data collection, analyzing, and reporting of results (Figure 4). Another step, outside the domain of government and academia, involves the community organizing a research group that conducts problem-solving research by collecting data, interpreting the data, and applying the findings to the problem at hand. This strategy empowers the community to take charge of the challenges in their neighborhood. The community is involved at every level, which is crucial for public health promotion and intervention activities. Action is required from individuals outside of the disadvantaged group and from those within the community to ameliorate the situation.

Figure 3

Community Based Research Model

Figure 4

Levels of Participatory Research

Levels of Prevention: Primary, Secondary & Tertiary

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Benjamin Franklin

Strategies to develop intervention and preventions to improve the public and their communities are part of the public health initiative. As a proponent of preventative measures, public health has invested in various areas aimed at reducing health disparities, collaborating with organizations that share the same goals. Given that the United States has some of the worst health outcomes and spends the most on health care delivery among peer countries, public health advocates had long sought such a guaranteed investment in preventive health services, including a “wellness trust” proposed by then-Senator Hillary Clinton (D-NY) (Fraser, 2019). The Prevention and Public Health Fund, popularly known as “the Fund,” was the nation’s first broad-based required source of money for public health programs to improve health and limit the development of public health care expenses. Between 2010 to FY2022, the fund was authorized for $18.75 billion, then $2 billion yearly after that (Fraser, 2019).

Prevention can be described as the activities taken to help people reduce their health risks. From a public health lens, prevention is significant for decreasing morbidity and mortality. Prevention comes in all forms, such as education, counseling, support groups, exercise, screenings, immunization, medical services and visits, and other activities that could lead to disease or injury. Leavell and Clark were the first to develop preventative procedures in the 1940s. According to the researchers, preventive measures do not need to be implemented until man is exposed to the causative substance. It was assumed that the “man” had the ability to stop the causative agent and prevent the cause from progressing further (Clark, 1954). Furthermore, their research found that prevention depends on understanding climatic circumstances, biologic and geographic environments, anopheline mosquito habits and traits, and human habits and customs (Clark, 1954). The three preventions were developed in the context of the epidemiologic triangle model of disease causation. If used appropriately, prevention could be the best hope for reducing unnecessary demand on the healthcare system. These preventions are primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention (Figure 5). Although public health promotion could be found in every prevention, these professionals are more proactive in the primary and secondary prevention stages.

Primary Prevention

In primary prevention, the person is seen as healthy and free of illness symptoms. For example, prevention begins before any signs or symptoms of disease and tries to diminish or remove causal risk factors, avoid disease onset, and hence lower disease incidence (Compton & Shim, 2020). The goal is to eliminate the possibility of a disease ever arising. One goal is to reduce the risk of disease in healthy people by education, promotion, and encouraging healthy lifestyle choices. The at-risk population is the primary preventative target group.

Example- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the COVID-19 vaccine is a type of primary prevention for everyone who is eligible. This preventative measure benefits the entire community because it reduces the risk of catching the Coronavirus, and boosters keep variations at bay (Alpha, Beta, Omicron).

Secondary Prevention