3 The Corporate Class in American Politics

Introduction

The promise of living in a democracy is clear and simple: A democracy gives everyone an equal voice in choosing the people who will represent the interests of those who elected them. In this scenario, it doesn’t matter whether you are Jamie Dimond, the billionaire CEO of JPMorgan Chase, or a minimum wage teller at a Chase Bank branch. One vote, one person. In principle, moreover and far more importantly, since the number of minimum wage workers alone vastly exceeds the number of billionaire CEOs and the entire monied class—in 2022, nearly one-third of American workers, or 52 million people, earned $15 an hour or less (OXFAM 2022)—elected representatives should generally make decisions that reflect the interests of minimum wage voters over the interests of billionaires.

When middle class voters are added into the mix, the case is even stronger since minimum wage workers plus the middle class account for at least 90% of the country’s population. After all, if the interests of ordinary voters are routinely ignored or dismissed, then elected representatives—from the president to senators, to individual members of the House of Representatives—would invariably lose in the next elections and be replaced with, well, more representative representatives, right? Relatively few people in the US, of course, believe this is the case. A 2020 Pew Research poll supports this point: According to the poll, more than 80% of Americans said that large corporations and the wealthy, as well as politicians, had “too much power” (Igielnik 2020).[1] And they are not wrong. As one pair of scholars, Benjamin Page and Martin Gilens carefully document in their book, Democracy in America? What Has Gone Wrong and What We Can Do about It, “the best evidence indicates that the wishes of ordinary Americans actually have had little or no influence at all on the making of federal government policy.” More to the point, they continue, “Wealthy individuals and organized interest groups—especially business corporations—have had much more political clout. When they are taken into account, it becomes apparent that the general public has been virtually powerless” (2017, 53).

As I suggested in Chapter 1, it’s easy to shrug your shoulders and conclude, “That’s just the way things are. The rich are naturally going to be more powerful than anyone else.” Another way of saying this is that the rich—and especially the corporate class—are always going to dominate the political process, which means that their interests are given the highest priority by elected representatives. To be sure, as I also highlighted in Chapter 1, in any market-based democracy, the corporate class has a significant degree of power and will use that power to exercise influence over the political process. But this does not mean that other classes are necessarily “powerless.”

Our comparative look at peer democracies tells us that, in many countries, corporate power can be and is counterbalanced such that the interests of the low-income and middle classes, if not placed first, are at least prioritized in some important areas. Significantly, we don’t have to look outside the United States to understand that corporations have not always been or are destined to be all-powerful. In fact, for a big part of the 20th century—from around 1930 to the 1970s—the power of the corporate and monied classes in the United States was far more limited than it is today (and prior to the 1930s). Looking at changes over time within the same country, by the way, is an important and very useful type of comparative analysis. It is what researchers refer to as a within-case comparison. Most simply, this is when a researcher examines the same unit of analysis (e.g., the United States) over time, identifies a key turning point or significant change (e.g., a major weakening or strengthening of corporate power influence) and then looks for other changes that can explain the basis or reason why things changed.[2]

The Shifting Power of the American Corporate Class

While the corporate form of organizing a business has been around for centuries (as far back as the 17th century in England), the practice of “organized interests” (i.e., individual corporations), getting “favors” from the state in exchange for money is a more recent phenomenon. Perhaps not coincidentally, this practice, according to Stephen Barley (2010), first began in the United States after the formation of political parties. As Barley explains it, “After 1824, when parties formed, politicians used political appointments to reward financial supporters. Contracts were also granted to corporations with the understanding that recipients would contribute to the officeholder and the party that secured the contract” (781). The connection between political parties and the corporate class would, over time, become a defining feature of American politics, although for more than a century, corporate influence tended to be on an individualized basis (that is, single corporations using their economic resources to influence political parties or the government) as opposed to on a collective basis whereby corporations banded together to influence policy in a manner that reflected their shared or common interests. In fact, as Barley notes, “it was not until the mid-1970s that firms [collectively] began to organize specifically to shape federal policy” (ibid.).

Tellingly, the motivation for organizing into a more coherent and thus more powerful political presence was a reaction to a gradual loss of political influence, which started in the 1930s, in response to the Great Depression. Although corporate power ebbed and flowed after the mid-1940s, the 1960s experienced the emergence of a powerful grassroots movement (i.e., collective power) in the United States. This was a time, as Perrow (2000) notes, that “saw the birth of environmental and public interest groups, which quickly learned to work together against corporations in Congress and the Courts.” The result, in the 1960s and into the 1970s, was a “string of political defeats” for corporations (Barley 2010, 781) In particular, this was a period during which three important new agencies reflecting the interests of ordinary Americans were established: the Environmental Protection Agency (1970), the Occupational Safety and Health Agency (1970), and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (1972). These agencies, and the laws that gave birth to them, not coincidentally, were created under a Democratic Party-controlled Congress, although they all received bipartisan support—the House vote for the EPA, for instance, was 375-1. Predictably, the American corporate class was unhappy with these developments; even more, it began to regard the federal government itself with “singular hostility,” a hostility that led corporations to “wage a protracted, ideological … battle against perceived encroachment on business prerogatives” (Eismeier and Pollock III 1986, 292).

The idea that the government was “encroaching on business prerogatives” is important to highlight, for it suggests that corporations were used to getting their way with American politicians. As I’ve already suggested, this was true for the most part and for most of American history. Perrow (2002) provides a reason. To wit, despite the perception that the American state has always had a great deal of capacity, that was not the case in throughout the 1800s, when large-scale corporations first began to emerge. (Historically, it is worth noting, this points to another important difference between the US and many European countries, which tended to have much stronger states capable of reining in big corporations from a very early stage.) During a critical period of corporate development in the US, then, there was not a strong and steadfast check on the concentration of corporate power. Perrow summed up the situation as follows: a “weak state will allow private organizations to grow almost without limit and with few requirements to serve the public interest”; in addition, “private organizations will shape the weak state to its liking …”. (See Box 3.1 for a discussion of strong and weak states.)

On the surface, though, there was an important law passed at this time, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which was ostensibly designed to curb corporate power by preventing the monopolization of industry. Moreover, it was the product of intense public anger over the seemingly unceasing concentration of economic power, which suggests that the state was listening to ordinary people. But there is evidence that the law was meant to be an “ineffective sop to public opinion, a public relations smokescreen …”, and this proved to be the case over the first decade after passage when it was ironically applied only against labor unions. Over a longer stretch of time, though, it did become a somewhat effective tool against corporate concentration.

One reason was that the courts began to interpret the law more expansively than intended by the legislators who passed it (Dickson and Wells 2001); it is also the case that the state was gradually acquiring greater capacity, that is, it was no longer a weak state. Nonetheless, and despite some successful applications of the Sherman Antitrust Act—two notable cases were against Northern Securities Company (a railroad holding company) and Standard Oil—the turn of the 20th century still saw the rise of 200 of the biggest corporations of the time, most of which remain powerful companies today (Perrow 2002).

Box 3.1 Strong and Weak States: A Brief Explanation

The terms “strong state” and “weak state” are easy to misinterpret. In particular, strength and weakness don’t necessarily refer to coercive or military power per se. Rather they refer, first, to the ability or capacity of state actors to make and enforce decisions independently of the interest of non-state actors, such as corporations. A state that is entirely “captured by” or unable to make decisions without the consent of powerful corporate actors, for example, is not a strong state. Second, the capacity of state is determined by its power to authoritatively regulate activities within a country’s borders as a whole. These activities include taxation and regulation of economic activities, as well as maintaining order within society. A state that is constantly challenged, say, by criminal gangs or warlords (e.g., Haiti) who effectively control parts of a country is not a strong state. Third, state capacity is determined by the internal coherence and competence of the state apparatus. If the parts of a state bureaucracy work at cross-purposes or are in outright opposition and/or if the state bureaucracy is incompetent (unable to carry out essential tasks and responsibilities), the lack of coherence and competence weakens the state.

Strong states are not necessarily repressive or dictatorial states; indeed, most scholars agree that a strong state is necessary for democracy to thrive, since for democracy to survive and thrive, the rules of democracy must be authoritatively and effectively enforced (see Tilly 2007). At the same time, many strong states are oppressive authoritarian ones. A good example is China, which had all the elements of state capacity in spades well before the country adopted capitalism. One result has been a state that exercises strong control over the corporate class.

Interestingly, the ability and willingness to exercise “strong control over the corporate class” also seems to be increasingly the case in Donald Trump’s second term. Powerful corporations have been bullied by the administration threats to increase tariffs or use other tactics that threaten corporate profits.

State-Sanctioned Violence against Labor

Another important sign of corporate power in the 19th and early 20th centuries was the largely unfettered use of force—sometimes with deadly consequences—against organized workers, often backed by governmental authorities at the state and federal levels. Indeed, the willingness to use state-sanctioned force against workers who dared to go on strike was considered a badge of honor by politicians at the time. In 1876, for instance, then Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes ordered the state militia to halt a coal miners’ strike; later, his success in crushing the strike was included in the list of attributes that apparently made him a good candidate for president (Walker 2016). (Hayes won the presidential election of 1876 and served as president from 1877 to 1881.)

During the 1800s and into the early 1900s, state militias or Pinkerton “detectives” (basically, a private paramilitary force[3]) were mostly used in labor disputes, but federal troops were also sent in on multiple occasions, almost always on clear behalf of corporations. Importantly, state/corporate actions against workers not only resulted in thousands of injuries, but also resulted in at least 671 reported deaths between 1877 and 1947, with perhaps hundreds more unreported deaths (Sexton 1991). One infamous incident, known as the Ludlow Massacre, occurred in 1914 in a strike by 11,000 miners who worked for the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company (a subsidiary of Standard Oil owned by John D. Rockefeller). Here’s how Howard Zinn, best known for his A People’s History of the United States (1995), described what happened:

In April 1914, two National Guard companies were stationed in the hills overlooking the largest tent colony of strikers, the one at Ludlow, housing a thousand men, women, children. On the morning of April 20, a machine gun attack began on the tents. The miners fired back. Their leader, . . ., was lured up into the hills to discuss a truce, then shot to death by a company of National Guardsmen. The women and children dug pits beneath the tents to escape the gunfire. At dusk, the Guard moved down from the hills with torches, set fire to the tents, and the families fled into the hills; thirteen people were killed by gunfire (cited in Zinn n.d.).

Despite the death and injury inflicted upon workers, in the same way that lynching of Black Americans and other minorities was generally ignored, corporations were rarely held to account by the state governments or by the federal government for the death and injury they caused. Consider this: Following the Ludlow Massacre, in which 66 men, women, and children were killed, not a single guardsman or “private detective” was charged with any crime (History.com Editors 2021). The lack of action against sometimes deadly violence directed at workers reflected an American legal system that, at the time, was heavily tilted in favor of business interests. A justice on the New York Supreme Court, just to give a sense of the heavy legal bias for corporations, flatly declared, in 1921, that the courts “must always stand on the side of capital and the captains of industry” (Sexton 1991).

The position of US courts, it should be noted, stood in stark contrast to British system, where, by 1865, unions were “generally accepted as legitimate despite continuing employer complaints”; moreover, by 1871, British courts had established that collective bargaining agreements were legally enforceable (ibid.). It took the United States more than half-a-century to “catch up” to Britain, with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act. The Wagner Act, which can be traced back, at least loosely, to the Ludlow Massacre more than 20 years earlier, finally guaranteed the workers the right to “self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, [and] to bargain collectively” (cited in Legal Information Institute n.d.).

The Decline of Corporate Power: An Interlude

The passage of the Wagner Act took place during a particularly important period in American history, a period in which the country was dealing the economic shocks of the Great Depression (1929-1939). The economic devastation of the Great Depression helped push the federal government to a more progressive stance. In particular, the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (popularly known as FDR) in 1932, marked the first time that a strong federal government embraced a pro-labor position and demonstrated a concern, through effective policies, for ordinary Americans.

The Wagner Act, then, was only one of many major legislative outcomes, which included the Social Security Act; the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (which established the Food and Drug Administration or FDA); the Works Progress Administration designed to ease unemployment by funding major public works projects (e.g., hospitals, schools, roads, and so on); the Housing Act; and the Wealth Tax Act designed to redistribute wealth in part through an income tax of 79% on income over $5 million (at the time, the law applied to a single individual, John D. Rockefeller). While large corporations were generally unhappy with the policies of the New Deal, they were particularly unhappy with the pro-labor turn of the federal government. Giving workers the legally protected right to organize and engage in collective bargaining and collective action was a serious blow to the interests of big business and one they would definitely not take sitting down, a point I will expand upon shortly.

Notably, though, 1930 marked the beginning of an extended period of dominance by the Democratic Party. New Deal policies, while abhorrent to the corporate class and their main political ally, the Republican Party, were embraced by the American public. After his electoral victory in 1932, in which he won 57.4% of the national vote and 472 electoral votes, FDR did even better when he ran for a second term as president: He garnered 60.8% of the popular vote and won 523 of 531 votes in the Electoral College in the 1936. That same year, the Democratic Party also took nearly 77% of the seats in the House of Representatives and 75 of 100 Senate seats. FDR won a third term in 1940 and a fourth term in 1944, both times with a declining popular majority, but still overwhelming electoral college victories. During his fourth term, FDR died while in office and was succeeded by his vice president, Harry S. Truman, in 1945.

During FDR’s unprecedented run as president—which led directly to the 22nd Amendment setting a presidential limit of two terms (ratified, at breakneck speed, in 1951 after being approved by Congress in 1947)—it is fair to say that American democracy was, in important respects, the most democratic it had ever been. This is not to say that it the “greatest democracy.” It was unequivocally not. After all, this was not only an era that continued to deny civil and voting rights to Black Americans, especially in southern states, but also an era in which lynching was still common with little to no fear of legal consequences—of all the lynchings committed after 1900, only 1% resulted in the perpetrator being convicted (cited in Equal Justice Initiative 2017).

FDR, in fact, was constantly pressured to support federal anti-lynching legislation but he declined to do so for pragmatic reasons; basically, he wanted to ensure he would get sufficient congressional support for his higher priority New Deal legislation (Archives Unbound: African American Studies n.d.). FDR also signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, which led to the mass incarceration, without due process, of more than 110,000 Japanese aliens and American citizens of Japanese descent. The order reflected decades of anti-Asian racism. In short, to repeat, this was not an era of ideal democracy; instead, it was an era in which the interests of the white working and middle classes were given greater priority by the presidency and by Congress than ever before.

While Truman did not break from significantly from FDR—he even proposed a universal national health insurance program (Markel 2015), something that most European countries had already achieved by 1945—efforts by the corporate class and the Republican Party to weaken the Democratic Party’s decade-long stranglehold on policy, and on its pro-labor position in particular, had begun to bear fruit. One of the clearest manifestations of this was the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 (also known as the Taft-Hartley Act), the passage of which overcame a Truman veto.

The Taft-Hartley Act has been labelled “the most antilabor law in the English-speaking world” (Sexton 1991, 155) and was one of 250 union-related bills introduced into both houses of Congress in 1947. While a detailed discussion of the Taft-Hartley Act would be useful, suffice it to say that it reflected the lobbying efforts of, among others, the National Association of Manufacturers and was designed to neutralize organized labor by restricting the capacity of unions to stage concerted actions, especially strikes (UpCounsel n.d.); it was also artfully framed as an anti-communist measure in order to define unions as un-American.

Such tactics, it is important to highlight, were and are “powerful” discursive strategies. Indeed, the theme of painting unions and anyone who supported unions as un-American or anti-American became a major motif of American politics in the 1940s and 1950s. This was a time when Senator Joseph McCarthy became a household name due to baseless but highly destructive crusade against “communists” both inside the US government and in American society more generally.

His “anti-communist” crusade was dubbed McCarthyism, a term that still has strong resonance in the United States as those advocating for progressive policies are frequently labeled as communists and are accused of being anti-American. During the 2020 Democratic primaries, for instance, the Washington Times (a conservative news outlet, not to be confused with the more liberal Washington Post), asserted that most of the Democratic Party candidates were closeted communists and fundamentally anti-American (Chumley 2020).[4] Even more recently, Donald Trump called the winner of the Democratic primary for mayor of New York in June 2025, Zohran Mamdani (who describes himself as a Democratic Socialist), a “100% communist lunatic” (Marcus 2025).

Reasserting Control, Gaining Dominance through Organization

The eclipsing of corporate class power between the 1930s and 1960s helped demonstrate to members of the corporate class that, despite their material and structural power in the American economy, something more was needed in the context of a democratic system and in the face of an increasingly strong state. That is, to guarantee that their interests would be systematically protected and prioritized by the federal government (as well as individual state governments), they needed to find a way to further empower themselves.

This said, there was already an understanding that concerted action through closer inter-corporate cooperation (i.e., organizational power) could be an important and even indispensable tool. The Taft-Hartley Act, as I just noted, was at least partly a product of broad-based corporate lobbying through the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). NAM was founded in 1895 originally to promote manufacturing sales through increased foreign trade; by 1903, though, its main priority switched to a focus on combatting, in the organization’s own words, “union militancy” (National Association of Manufacturers 2022). NAM, however, is one of only many business associations that brought together firms—some of which might otherwise been in direct or at least indirect competition with one another—for the purpose of influencing public policy. Before discussing these other organizations, it would be useful to take a step back to get a broader view of the many interconnected organizations, strategies, and tools the corporate class has adopted to exercise influence over the political or democratic process in the United States.

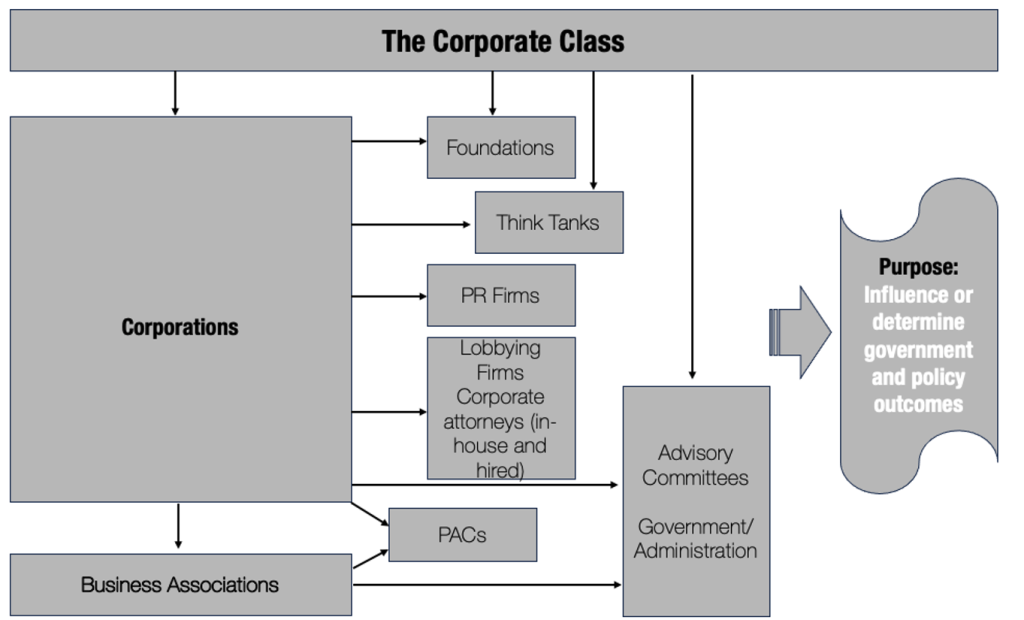

Box 3.2 below provides an admittedly overly simplified rendering of the organizational network developed by the corporate class, most of which was put in place from the 1970s onward. There are seven main elements listed: (1) Business Associations; (2) Political Action Committees or PACs; (3) Foundations; (4) Think Tanks; (5) Public Relations or PR Firms; (6) Lobbying Firms (and Corporate Attorneys); and (7) Administrative Appointments and Advisory Committees. The list is based on (with slight modifications) research done by Barley (2010) and Domhoff (2021), both of whom provide a much more a complex depiction showing the nature of the relationships between the various elements. With the goal of keeping things as simple as possible, it is enough to understand that, over the years, corporations have built up an extremely well-funded, interlinked, and effective network of organizations, all of which, to repeat, has one overarching purpose: To influence and shape the political process so that the interests of the corporate class are prioritized, through government policy and action, over the interests of low-income workers, the middle class, and everyone else in American society.

This is not to say that the interests of the corporate class never intersect with the interests of the broader American public; certainly, there are situations in which corporate class interests benefits Americans more generally. Businesses, after all, create jobs and produce goods and services that people both want and need. To the extent that public policies encourage business growth and more efficient production in general, a potential win-win situation is created, even if the benefits to the corporate class are disproportionate. However, this isn’t always true. A case in point: Businesses may demand policies or engage in unregulated practices that, quite literally, put “profits over people,” such as knowingly releasing dangerous or toxic substances in public waterways. During the first Trump administration, for example, pressure by businesses led the federal government to “strip away Clean Water Act protections …”, which paved the way for toxic chemicals to be dumped into the country’s river, streams, and wetlands (Rilling 2020).

Box 3.2 (Simplified) Organizational Network of the Corporate Class

Elements of the Organizational Network[5]

It’s always a bit tricky, in an introductory textbook, to get too much into the weeds, that is, to provide a lot of detail, which may or may not be helpful for understanding. Nonetheless, it is necessary to say something about each of the main elements of the organizational network of the corporate class, since the network has become the basis for corporate class dominance in American politics and a key reason, although not the only one for sure, for the weak state of American democracy in the first few decades of the 21st century. With this in mind, in the following pages I provide brief and purposely simplified descriptions of the seven major elements of the organizational network of the corporate class. Still, some degree of detailed (i.e., “in the weeds”) discussion is unavoidable to ensure that each element is covered adequately.

Business Associations

Most simply, a business association is a stand-alone organization whose members are primarily businesses, from the smallest to the largest. They may all be in the same industrial or business sector (which can be referred to as trade association) or they may represent a diverse range of industries and businesses. The basic purpose of a business association is to promote the shared interests of the members. This is frequently done through lobbying, which the IRS simply defines as “attempting to influence legislation” (IRS 2023). While lobbying isn’t the only activity of business associations, it is, arguably, the most important and one that draws in a huge amount of money and other resources. The US Chamber of Commerce, which was founded in 1912, offers the clearest example.

The Chamber purportedly represents three million businesses in the United States, but almost 95% of its funding comes from just 1,500 corporations (Katz 2015). It uses this money, in large part, to fund lobbying efforts. In 2023, according to OpenSecrets.org (2023c), a go-to source for information on political spending, the Chamber spent more than $1.8 billion on lobbying between 1998 and 2023 (as of July that year), which put it at number one on the list of top spenders. Other major spenders over that same period include the National Association of Realtors, the American Hospital Association, the American Medical Association, Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers of America, and the Business Roundtable.

Notably, also among the top spenders are individual companies such as GE, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, AT&T, Verizon, and Exxon Mobil—more recently, in 2022, Amazon, Meta, Pfizer, Comcast, and Alphabet made it into the top 20. Altogether, business associations and individual corporations accounted for almost 90% of all the money spent on lobbying in 2022, while “ideological groups” accounted for about another 5%. Labor, by contrast, accounted for paltry 1.3% to total spending on lobbying that year (OpenSecrets.org 2023a). The last statistic is important to highlight, since corporate supporters often charge organized labor with having undue influence over federal policy; yet, it’s clear that, in terms of spending, labor’s influence is extremely limited.

This said, while there are many business associations, a few stand out. The US Chamber of Commerce and NAM are two of them, which have already been discussed. Another one is the Business Roundtable, founded in 1972, which was mentioned in passing in the preceding paragraph. The Business Roundtable is an influential association, in part, because it spent over $20 million on lobbying in 2022 and over $29 million in 2021 (OpenSecrets.org 2023c). But also because it serves as a strategic hub of sorts for CEOs of the country’s “leading companies” (Business Roundtable n.d.). On this last point, the Roundtable has CEO-led policy committees that meet every few months to “discuss current policy issues, create task forces to examine selected issues, and review position papers prepared by task forces” (Domhoff 2021, 101).

Significantly, membership is restricted to CEOs themselves, who are expected to directly lobby policymakers in both political parties on behalf of the business community on the premise that personal interaction between corporate leaders and policymakers—in addition, of course, to tens of millions spent on lobbying efforts—would be politically effective (Barley 2010). The Roundtable’s board of directors in 2023 includes a who’s who of corporate kingpins: Mary Barra (CEO, GE), Greg Adams (CEO, Kaiser Permanente), Tim Cook (CEO, Apple), Jamie Dimond (CEO, JPMorgan Chase), Lynn J. Good (CEO, Duke Energy), and 20 other prominent CEOs representing a full range of industry sectors.

Lobbying Firms and Corporate Attorneys

Business associations and individual corporations often use their own personnel, including (as I noted above) their CEOs, to directly lobby legislators. However, it is often more efficient and effective to hire a lobbying firm; this is the case for issues that require knowledge that is general to an industry and in which there is little potential for “leakage” of sensitive, firm-specific information (Figueiredo and Kim 2004). Professional lobbying firms may also have deep legal expertise, intimate knowledge of the “lobbying game,” crucial and often highly personal legislative connections, and offer other advantages that few but the largest companies have in-house.

Of course, lobbying firms also get results, which means shaping policies in ways that benefit their clients. One recent example: During the first part of President Biden’s administration, when a bipartisan infrastructure bill (the “Build Back Better” Act) was first introduced, lobbying firms went into overdrive. As the Karl Evers-Hillstrom (2022), writing for The Hill (a news outlet focused on congressional politics), noted, “Corporate lobbyists successfully pushed lawmakers to make industry-friendly changes to virtually every section of Biden’s social spending and climate plan, including the bill’s provisions around corporate taxes, drug pricing, clean energy and paid leave. Democrats’ razor thin majorities in Congress made it easier for lobbyists to influence the bill.” In the same story, Evers-Hillstrom pointed out that 2021 was a record year for lobbying firms, as the leading “K Street” firms, as they are commonly called, earned record revenues—after already breaking their earnings’ record in the previous year.

Another core reason that lobbyists (both those that work in corporations and those who are outsourced) are effective is because they are willing to do the work that elected representatives are supposed to do. That is, lobbyists often write the bills that are debated in and sometimes passed by Congress (Chang 2013). Here’s how one writer explained the process in posing the question, “Who actually writes congressional bills?”:

You’d probably assume it was our elected officials who wrote them, right? The people who swore an oath to represent their district or state? The people we elected to become lawmakers? What a world that would be. Unfortunately, we live in a world where Congresspeople and Senators don’t write the bills that get voted on. Their staff aren’t even the ones who write the bills. So who does? That’s right, you guessed – paid lobbyists working on behalf of multinational corporations and special interests.

If you think we’re exaggerating this, think again. Because Congresspeople and Senators are so obsessively preoccupied with fundraising in order to run their re-election campaigns, they don’t have any time in the day to actually, you know, draft legislation. Sometimes it’s handed off to their staff, but frequently, members of Congressional and Senate staffs are so overworked, overstressed, and underpaid, that they barely have the bandwidth to read bills, let alone author them (Furlin 2023).

Many lobbyists are attorneys and many corporate law firms establish in-house lobbying departments, often innocuously labeled as “Government Relations.” Here’s how one run-of-the-mill K Street law firm proudly described its work in governmental relations:

We have the experience to reach decision-makers at any level from our offices in nine states and Washington, D.C. Our 20 government relations professionals and support staff include individuals who have served as counsel to legislative leaders, elected executive officials, administrative agency directors, state and national political party leaders and as White House appointees. Our government relations approach brings together professionals who possess complementary legal skills, knowledge of substantive and relevant government policy, and contacts in both major political parties. We advocate client interests with elected and appointed executive officials and legislators and their staff members. The result is understandable government relations services rendered by experienced practitioners (Barnes & Thornburg 2023).

Together, stand-alone lobbying firms and law firms with governmental affairs department have become a major presence in Washington, D.C. since the 1960s. The statistics bear this out. In the mid-1960s, there are around 3,000 to 4,000 individual lobbyists in D.C. (cited in Barley 2010), but by 1988, the number shot up to at least 10,415 and peaked in 2007 at 14,815. In 2022, the number declined to 12,673 (OpenSecrets.org 2023b), but was nonetheless still a huge number in relation to the main targets of lobbying, namely, members of the House of Representative (435) and Senators (100). In other words, in 2007, there were about 28 lobbyists for every single member of the House and Senate. Keep in mind, too, that a very large proportion of former members of Congress become lobbyists. A 2019 report by Public Citizen showed that nearly two-thirds (59%) of former members of the 115th Congress (2017-2019) who found jobs outside of government ended up working as lobbyists (Zibel 2019).

Foundations, Think Tanks, and PR Firms

Words and ideas matter and perception and image can play crucial roles in politics and the policymaking process. Thus, while lobbying is an obviously effective practice as evidenced by the vast amount of money spent, over many decades, to directly influence elected representatives—i.e., it’s unlikely that the corporate class would spend billions of dollars on something that doesn’t work—it is still the case that the corporate class (plus the monied class) constitute a minuscule percentage of the voting population. In a democracy, then, they need broad support for their activities and practices. This is especially the case when corporations and large corporations, in particular, are distrusted by the American public or thought to have “too much power,” as noted above.

Partly for this reason, the corporate class has long endeavored to shape or control the narrative on the need for and even sanctity of private enterprise. In 19th and early 20th centuries, as I noted earlier, this meant associating organized labor with “socialism,” which also meant associating socialism with being fundamentally “un-American” or “anti-American.” Later, socialism was conflated with communism, which was a particularly effective strategy during the Cold War period, a period that saw a supposed struggle between the “Free World” (i.e., the capitalist world led by the United States) and the “Communist World,” which was decidedly unfree and dominated by totalitarian and oppressive states. (Note. Many “Free World” countries were also dominated by equally oppressive authoritarian states that provide little freedom to their citizens.)

Whether socialism or communism (see Box 3.3 for a brief discussion of these two terms), the narrative was clear: Both are not only anathema to private enterprise, but also, if allowed to take hold in the United States, would quickly lead to the country’s economic, political, and even moral ruin. FDR’s highly popular and successful New Deal policies, however, undermined, albeit only partly, the fear of socialism or at the least the fear that a strong state interfering with private enterprise was necessarily bad. If the American public wasn’t afraid of either socialism or big government, the corporate class feared, that would make their task of regaining control over the political process much more difficult.

Thus, to make a long story short, by the 1960s, the corporate class understood that it needed to reinvigorate the narrative. This led to a more systematic effort valorize private enterprise and an unfettered market, and to inject a pro-corporate perspective into both the intellectual and popular discourse (Barley 2010). One way to do this was through the establishment of a “think tank,” which is basically a nonprofit organization made up of experts set up to conduct research on certain topics and to disseminate the findings from that research to a wider audience.

A general objective of think tanks is to influence how people understand an issue; put another way, think tanks are designed to shape public opinion. To accomplish this, think tanks not only publish research papers, but also hold conferences to which journalists and congressional staffers are invited, write op-ed articles (for a range of mainstream news sources whether liberal or conservative), post regularly on social media platforms such as Twitter, create content for YouTube, testify before House and Senate hearings, and appear on local and national television. Media exposure has become a very important function for think tanks (Weidenbaum 2010).

Box 3.3 Socialism and Communism: A Brief Discussion

In the United States, both the terms socialism and communism are misunderstood by the vast majority of the population, including many professors and otherwise well-informed people. There are good reasons for this in the US. The main reason is that there has been a concerted effort to distort their meaning for political purposes. And, with no influential labor party, there was very little pushback against the one-sided narrative of the corporate class and their supporters (Sexton 1991).

This said, socialism refers to an economic and political system in which property and resources are not only publicly owned (by the state), but also in which the goods and services are provided to consumers through a non-market mechanism (e.g., government-set prices). In this definition, China is a capitalist country even though the state or the Chinese Communist Party controls many of the largest firms or state-owned enterprises (SOEs), since SOEs produce goods and service for sale in a market.

Socialism was originally understood to be a transitional stage between capitalism and communism. It’s important to highlight the term “transitional,” since it tells us, in principle, that socialism wasn’t possible until a country was first capitalist. The reason is simple: Capitalism is a powerful economic system that creates the material basis for socialism. Thus, it’s no surprise that all countries that tried to become socialist before going through capitalism ended up failing economically. If socialism is a transitional stage, then communism is the final stage.

Logically, if a country does not move through capitalism first and socialism second, it cannot become communist. In this regard, there has never been a communist country. To be sure, countries have called themselves communist, but that doesn’t make them so. On this point, keep in mind that many countries call themselves “democratic,” such as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or North Korea. It’s clear, though, that North Korea has never been democratic.

So, what is communism? Simply put, communism is a stateless, classless, and moneyless society that produces enough to meet everyone’s needs so that they will be free to pursue their own goals without any constraints imposed on them by a state, class, or market. Sound utopian? It probably is, which is why there has never been a communist country.

For a useful and easy-to-understand discussion of socialism and communism, see the following video available on YouTube: “Communism vs. Socialism: What’s the Difference?” (2017) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrtDZ-LOXFw)

Before 1960s, there were few think tanks and most were non-partisan, although there were a handful of both liberal and conservative ones. Starting in the 1970s, reflecting the heightened effort to reshape public discourse, many more think tanks began to appear with the large majority having a pro-corporate orientation; by the 2000s, 29% of all think tanks were liberal, 29% moderate or non-partisan, and 42% conservative, which was a dramatic proportional reversal from before 1970 (Barley 2010).

The most prominent think tanks include the Brookings Institution, the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), the Cato Institute, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Brookings is considered a liberal think tank, while Cato, Heritage, and AEI are considered conservative. CSIS focuses on foreign policy issues and has made an effort to develop a non-partisan position. Weidenbaum (2009) refers to these five think tanks as the “DC-5.”

Importantly, over time, think tanks began to function more and more like lobbying firms in that they actively and directly tried to influence or shape specific policy decisions and broader policy directions. The Heritage Foundation is generally pointed to as the originator of this activist turn, which began in the late 1970s and early 1980s: In 1981, the Heritage Foundation sent newly elected President Ronald Reagan a nearly 1,100 page report “that became a policy blueprint for [the Reagan] … administration” (Philanthrophy Roundtable n.d.). During the Obama administration, the Heritage Foundation openly called for stopping tax hikes and repealing the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), while directly interacting with legislators and their staff through briefings and writing and analyzing legislative draft proposals on request (Heritage Foundation 2010).

More recently, the Heritage Foundation wrote a 922-page policy “blueprint” in anticipation of the second Trump administration. This is known a Project 2025 (click here to view a summary). While Trump tried to distance himself from and even entirely disavow the project during his campaign, since assuming office in January 2025, according to an analysis by Politico, “many of the conservative blueprint’s ideas have made their way into his early executive orders.” In fact, as Politico noted, “A side-by-side review … found dozens of cases where the president’s early executive actions have aligned with portions of the 922-page policy document, including some instances with nearly verbatim language lifted from the report to the White House” (Cruz, et al. 2025).

It is important to emphasize that even the Brookings Institution, a supposedly liberal think tank, has strong and less than pristine ties to the corporate class. Eric Lipton, an investigative reporter for the New York Times, uncovered a problematic relationship between Brookings and some of its corporate donors. As he described it:

Thousands of pages of internal memos and confidential correspondence between Brookings and other donors — like JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s largest bank; K.K.R., the global investment firm; Microsoft, the software giant; and Hitachi, the Japanese conglomerate — show that financial support often came with assurances from Brookings that it would provide “donation benefits,” including setting up events featuring corporate executives with government officials … (Lipton 2016).

Brooking’s relationship to corporate donors underscores a basic point: It costs money to operate a think tank. In 2010, to use the Heritage Foundation again as a representative example, the organization’s operating expenses were $163.9 million; as a long-established think tank (founded in 1973), most of its operating funds, by that time, came from individual contributions, although the lion’s share were from individual members of the corporate and monied classes. Another significant source of funding came and continues to come from private foundations, which are also an important element of the organizational network of the corporate class. Foundations are easy to overlook, at least in terms of their relevance to the power of the corporate class, in part because they generally seen as charitable and altruistic organizations, but this is not necessarily or even mostly the case.

To begin, many of the largest foundations were created by the corporate class and their corporate lawyers, in part to serve as major tax shelters into which they could funnel a significant portion of their wealth tax-free (Domhoff 2021). Money donated to a foundation provides three significant paths to tax savings. First, monetary donations are not included in the donor’s estate, thus making any donated assets free from state or federal estate taxes. Second, monetary donations qualify for an income tax deduction for the full amount contributed, up to 30% of the donor’s adjusted gross income. Third, donors do not have to pay any capital gains taxes if they give way appreciated assets, such as stocks or real estate, instead of giving cash to a foundation (Kagan 2022).

A prime example of how the monied class uses foundations almost solely as tax shelter is described by Jeff Ernsthausen, writing for ProPublica (2023). Ernsthausen highlighted the activity of Charles Johnson, a billionaire businessman and part owner of the San Francisco Giants. Johnson donated his mansion to his own foundation, with the promise that the $130 million house and estate—likely an inflated amount to increase the tax savings—would be open to the public every weekday from 9 to 5. The IRS granted the foundation tax-exempt status, which allowed Johnson to collect more than $38 million in tax savings over five years. However, instead of providing weekday access from 9-5 to the general public, “the foundation bestows tickets on a few dozen lottery winners, who receive two-hour tours, led by docents, most Wednesdays at 1 p.m.”

To be sure, some private foundations, especially those that are not funded directly by the corporate or monied classes, are genuinely charitable or philanthropic. But for the corporate class, in particular, foundations have an important function beyond philanthropy: They can redirect money they would otherwise pay in taxes—and over which, once in government coffers, they would have no direct control—to fund projects that further their personal and often self-interested goals.

In a sense, for the corporate class, establishing a foundation provides a way to get taxpayers to subsidize a “pet project.” The Heritage Foundation, in this regard, was originally a pet project. It was established by Joseph Coors, President of Coors Brewing, after he decided that conservatives needed think tanks of their own (Philanthrophy Roundtable n.d.). Another of the DC-5, the Cato Institute—which was originally the Charles Koch Foundation—was founded by Charles Koch in 1976 expressly to promote limited government and free markets (Bennett 2012). Koch is Chairman and CEO of Koch Industries and, in 2023, was worth $62 billion.

While some corporate class foundations have a clear ideological purpose, there are others that appear to be mostly geared toward the public interest. Perhaps the best example of this is the Ford Foundation, which was established in 1936 by Edsel Ford, then president of Ford Motor Company. Although Ford was motivated by a newly passed tax law, which imposed a 70% tax on large inheritances, over the years the Ford Foundation funded the development of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), adult education, arts and humanities fellowships, law school clinics (for providing pro bono representation to the poor), the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the Grameen Bank (which provides loans to the rural poor), and many other praiseworthy endeavors. The Ford Foundation may be exception, though, as even seemingly selfless corporate philanthropy is more often used as a public relations tool. This was the case for the tobacco giant, Philip Morris, which widely publicized its philanthropy initiatives as a way to offset the negative publicity from the harm that the industry’s products caused—up to 440,000 deaths annually in the US alone (Tesler 2008).

The reference to public relations is intentional. As I noted at the outset of this section, perception and image can play crucial roles in politics and the policymaking process. Corporations want to look good to the general public, but they also want to make their “opponents” (anyone who actively opposes corporate power and domination), look bad. The latter goal, in fact, has become far more important to the corporate class, which has long had and continues to have an image problem in the United States. (Keep in mind, even if the public is skeptical of corporations, as long as it firmly supports capitalism and “free enterprise,” that skepticism will not necessarily lead to anti-corporate policies.)

In any case, public relations (PR) firms have become extremely adept at manipulating public opinion on issues that matter to the corporate class. Eric Lipton, mentioned above, describes how one PR firm, Berman and Company, uses several tried-and-true strategies to disguise corporate involvement in efforts to discredit positions the corporate class is opposed to. One strategy is creating fake think tanks for corporate clients, lobbying firms, or business associations. The fake or sham think tanks produce ostensibly neutral or unbiased scientific analysis (supporting, of course, the corporate position) on issues such as minimum wage. The report is released to the media and then may be reposted on the corporation’s website and pointed to as an “authoritative” analysis done by a credible think tank.

To repeat the main point, though: The think tank, in this case, is the PR firm itself, Berman and Company. In the same vein, Berman and Company also creates fake organizations and websites—e.g., EmploymentFreedom.org, IncomeTaxFacts.org, the Center for Consumer Freedom—that support its corporate client’s position, but which appear to be completely unconnected (Lipton 2014). Barley (2010) highlights another example in which the Business Roundtable hired a PR company to “produce negative articles, ads, cartoons, and prepackage editorials” in an effort to undermine effort to establish the Consumer Protection Agency in the late 1970s. The material was sent to local newspapers, which often just republished them as legitimate news stories. The last step was to collect the stories from local sources and present to legislators as evidence of negative public opinion (originally cited in Akard 1992).

As the foregoing discussion makes clear, PR firms, in a sense, close the loop. That is, they demonstrate how individual corporations, business associations, lobbying firms, “think tanks” (even if some are fake), and PR firms have been integrated into an effective, technically legal, but also problematic network of manipulation and influence.

Advisory Committees and Government/Administrative Positions

Generally speaking, the corporate class can effectively influence the policymaking process entirely from outside the state (or government). That is, members of the corporate class do not have to serve inside the federal government to get their way. Nonetheless, it doesn’t hurt. Even more, it is the rule rather than the exception that members of the corporate class take on high-level appointments in the executive branch that put them in a position to introduce, advocate for (or oppose, as the case may be), and sometimes to directly implement, the preferred policy choices of the corporate class. They are also routinely appointed to presidential and departmental advisory committees, where their voices and opinions are enormously amplified compared to ordinary citizens. The most prominent appointed positions are those in the cabinet, which is composed of the vice president and all the heads of 15 major departments. Here is a list of the 15 major departments:

- Department of Health and Human Services

- Department of Defense

- Department of Labor

- Department of Agriculture

- Department of Veteran Affairs

- Department of Interior

- Department of Transportation

- Department of Justice

- Department of Education

- Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of Energy

- Department of Treasury

- Department of State

- Department of Commerce

There are also hundreds of federal agencies, some with significant institutional power, although as Forbes magazine article claims (one written by a senior fellow at a conservative think tank), “No one can even say with certainty anymore how many federal agencies exist,” despite the fact that they make most of the law in the US, rather than Congress (Crews 2017). Some of the more important ones, whose acronyms you likely know, include the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the United States Postal Service (USPS). As with cabinet positions, the heads of these and other agencies are appointed by the president with the “advice and consent” of the senate. And, as with cabinet positions, most of the appointees for the agencies of most interest to the corporate class, are members of or closely tied to the corporate class.

Careful research had demonstrated that, since the late-1800s, regardless of which party was in power, the corporate class has dominated the most significant appointed positions (Rabern 2009, Mintz 1975, Burch 1980, Salzman and Domhoff 1980). While this pattern was temporarily and partly interrupted in Obama administration, it came back with a vengeance under Donald Trump in his first term, who appointed wealthiest cabinet in US presidential history (although there was a lot of turn-over in his cabinet). Trump’s cabinet included several billionaires. More specifically, “[h]is secretaries of education, commerce, and the Treasury, as well as his first secretary of state were worth a total of at least $1.3 billion and as much as $2.9 billion …” (Sullivan 2021). Even more, Trump generally selected true blue members of the corporate class, including: Steven Mnuchin as Secretary of Treasury, who spent about 20 years at Goldman Sachs and had a net worth estimated at $400 million in 2019 (Alexander 2019); Rex Tillerson, CEO of Exxon Mobil, as Secretary of State (although he did not last long in the position); Wilbur Ross as Secretary of Commerce, once known as the “king of bankruptcy” for purchasing, restructuring and selling off steel makers and other industrial companies; Betsy DeVos, the richest member of Trump’s cabinet (with assets close to $2 billion), appointed as Secretary of Education; and Scott Pruitt, as head of the EPA, a former attorney general of Oklahoma, but one who was very closely tied to the fossil fuel industry (Sullivan 2021).

Pruitt is an instructive case. Despite being head of agency meant to protect the environment, he played a key role in President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate accord (a major international agreement addressing global warming), pushed for a smaller EPA budget, and approved at least 24 regulatory rollbacks (Bush 2018). It isn’t an exaggeration to say that Pruitt was like the proverbial wolf in sheep’s clothing: He did all he could to undermine environmental protections on behalf of fossil fuel industry to which he was beholden—after leaving the EPA (he resigned under a cloud of ethics violations), he used his industry connections to launch a private consulting business promoting coal exports (Thompson 2018).

President Joe Biden’s cabinet, as with Obama’s, is also a bit of exception as there are no former CEOs in the top positions. Most of his appointees are former politicians—e.g., Pete Buttigieg, former mayor of South Bend, Indian (Secretary of Transportation); Jennifer Granholm, former governor of Michigan (Secretary of Energy); Marty Walsh, former mayor of Boston (Secretary of Labor); and Gina Raimondo, Rhode Island’s first female governor (Secretary of Commerce). Biden also appointment Deb Haaland to serve as Secretary of the Interior; she was the first Native American to head any cabinet agency (and also a former House member). At the same time, there are critics who argue that Biden’s choices overall still evince a pro-corporate bias, even if it is far more toned down than Trump’s choices (for example of a critical evaluation, see Bean 2020). As I noted above, though, serving inside the federal government isn’t necessary for the corporate class to exercise dominant control over the policymaking process ….” (Charalambous, et al. 2024).

Following the resumption of his second term as president, Donald Trump put together a less conventional cabinet, composed primarily of individuals who expressed unequivocally loyalty to Trump and his agenda. Even so, he continued his practice of appointing billionaires and others with extreme wealth. Indeed, he exceeded even his first term. As ABC News put it, “President-elect Donald Trump … assembled the wealthiest presidential administration in modern history, with at least 13 billionaires set to take on government posts” (Charalambous, et al. 2024).

As with regulatory agencies, there are hundreds of federal advisory committees—each agency, such as the FDA, may have a dozen or more advisory committees—which are charged with providing expertise and advise on range of issues affecting federal policies and programs. While advisory committees are, on paper, designed to give the public an opportunity to participate in the government’s decision-making process, the membership of these committees, particularly those that deal with economic or business related issues, can sometimes be dominated by corporations. Barley (2010) provides an example of the Treasury Department’s Mutual Savings Association Advisory Committee, whose membership (in 2010) included CEOs of banks. In 2023, this was still true as all 10 members of the advisory committees were bank CEOs (Office of Comptroller of the Currency 2023). Admittedly, many and likely most committees are far more representative. In the FDA, for instance, the Clean Air Act Advisory Committee has a mix of scientists, members of non-profit organizations, state government officials, and industry representatives (EPA 2023). However, while dated, a study by Scholzman and Tierney (1986) emphasized how corporations are more likely to have members on multiple committees and often try to protect their interests by “failing to give public notice of scheduled meetings, closing them to the public, and giving only sketchy reports of the proceedings …” (quote from Scholzman and Tierney 1986; cited in Barley 2010, 793).

Political Action Committees (PACs)

The last element of the organizational network, for our purposes at least, are political action committees. Political Actions Committees are, most simply, (tax-exempt) organizations set-up to help elect or defeat candidates running for elected office, whether at the local, state, or federal levels. PACs can also support or defeat state ballot initiatives or propositions. Anyone can create a PAC; most represent corporate interests, although there are also well-funded labor PACs and PACs that espouse an ideological position or support particular policies, such as PACs that both oppose and support the right to abortion. Interestingly, the first PACs were created by organized labor back in the 1940s as a way to circumvent a law, the Smith-Connally Act, that prohibited labor unions from making direct contributions to candidates (i.e., an effort by the corporate class to disempower labor.) For ordinary PACs, there are strict limits on the amount they can give to individual candidates or to a national party committee, $5,000 and $15,000 respectively on an annual basis. In addition to ordinary PACs, there are so-called super PACs (more formally, independent expenditure-only committees), which have only been around since 2010. Super PACs are “super” because they can spend an unlimited amount of money on political campaigns as long as they don’t give that money directly to candidates or party committees and coordinate their spending with their preferred candidates and party.

After changes to campaign finance laws in the 1970s, it became much easier or corporations and business associations—as well as anyone else—to form PACs. Accordingly, between 1974 and 2016, the number of corporate PACs (that actively made contributions to candidates) increased rapidly from 89 to 1,460. Trade or business association PACs did not increase as rapidly, but almost doubled during this period from 489 to 879. Labor PACs, on the other hand, declined from 224 to 180 (Campaign Finance Institute 2017). More important than the number of PACs is their spending. Not surprisingly, corporate PACs vastly outspend labor PACs by a factor of 7:1. Equally unsurprising is that corporate PACs expect to get a “return on their investment.” That is, they expect that the candidates they help to elect—both Republican and Democrat alike, since corporate PACs like to place their bets on the “winning horse,” i.e., they support candidates who they expect will win an election—who will represent the interests of the corporate class. In this regard, as Peoples (2020) puts it, corporate PACs are the biggest givers “because they want to impact policy once the candidate is in office” (17). PAC contributions are not quid pro quo bribes, but they provide the people who fund PACs with access to politicians, which in turn gives donors greater capacity to influence policy. As Peoples also emphasizes, this strategy works.

Peoples makes another important point (among many): corporate PACs tend to be tightly connected to lobbying firms. “[T]he contributing arm (the PAC)”, he writes, “donates money, and then the lobbying arm (the firm and its lobbyists) actively seeks to sway policy. The PAC establishes the relationship and gets the ‘foot in the door’ via the campaign donation; the lobbying firm then attempts to influence policy, frequently reminding the politician of their past support (the contributions from the PAC)” (17). Business associations also play a role as they helped individual corporations form PACs and also suggest which candidates corporate PACs should support (Barley 2010). In this regard, PACs also help to close the loop.

Conclusion: The New Era of Corporate Dominance

Without an organizational network, corporations and the corporate class would still be powerful actors capable of getting what they want due primarily to their structural, material, and organizational power (keep in mind, corporations are themselves are a type of organization). In a democracy, however, there is always the risk that corporate power can be “subverted” by the general public who can vote for elected representatives who give priority to the public’s interests. This happened, at least to some extent, beginning with the New Deal in the 1930s and lasting, albeit in weaker form, until the 1960s. Members of the corporate class did not get together in the proverbial “smoke-filled rooms” to plan their counteroffensive against democracy, although they did often meet in boardrooms, members only country clubs, gala events and parties, and secretive retreats such as the Bohemian Grove—a spot where Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas met his billionaire “buddy,” Harlan Crow[6] (Sampson 2023). At the same time, it is very clear that members of the corporate class did make an ongoing series of intentional decisions to reassert and solidify their control over the political process in the United States. The organizational network discussed throughout this chapter is a product of these intentional decisions. Business associations, lobbying firms, think tanks, foundations, PR firms, and PACs may not all have been created by the corporate class to exclusively serve their interests—this definitively isn’t the case—but the corporate class understood the utility and even necessity of building and sustaining a network of organizations that could help them achieve their goals.

These organizations, it is important to highlight, form a type of network in that they have, over time, become linked together so, to quote from Aristotle’s Metaphysics, “the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something besides the parts,” which is where the more commonly heard phrase, “The whole is greater than the sum of the parts,” originally comes from (cited in SE Scholar 2019). In other words, the connection among the elements creates an important degree of synergy, which has significantly enhanced corporate class power over the decades. The result, as I suggested at the beginning of this chapter, has been an undermining of American democracy. While this chapter has already presented some evidence to support this claim, more evidence will be provided as the remainder of the book unfolds. At the same time, if it’s true that the organizational network of the corporate class, which is a relatively recent phenomenon, is as crucial as laid out in this chapter, that implies that race isn’t as significant as I argued in Chapter 1. This is not the case: Race/racism has played in integral role in the development of American democracy since the very first days of the republic and even before. This will be the topic of the next chapter.

Chapter Notes

[1] Technically, the question asked respondents if big corporations and the wealthy (they had eight other choices, too) have too much power and influence in the economy, but it is fair to say that having too much power in the economy translates into have too much power and influence over the political process as well.

[2] For further discussion of the within-case comparison, see Goertz and Mahoney (2012) and Lim (2016).

[3] For further discussion of the Pinkerton Detective Agency and its key role in union busting, see Frantz (2018), who refers to Pinkerton as a paramilitary force.

[4] When president during his first term, Donald Trump provided another example. He once stated that a quartet of Democratic Party progressives—namely, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib, Ilhan Omar, and Ayanna Pressley (all women of color)— “hate our country” and “can leave” if they don’t like living in the United States (cited in Harrington 2019). While he didn’t call them communists, Trump’s language was a slight alteration of the timeworn McCarthyite phrase, “America, love it or leave it,” which was used in an effort to discredit anyone who questioned the legitimacy of McCarthy’s efforts.

[5] This entire section follows closely along the work of Barley (2010) and Domhoff (2021). At the same time, my discussion, while broadly and organizationally similar, includes my own thoughts, information, and analysis.

[6] A report by ProPublica first revealed the relationship between Thomas and Crow, the latter of whom is a Texas billionaire and Republican “megadonor.” After a little digging by reporters at ProPublica, evidence came to light that Thomas had traveled, for free, on Crow’s private plane on multiple occasions, over several decades, both within and outside the US. After the initial story broke, it was discovered that the financial connection was even deeper. Crow, for instance, purchased the home of Thomas’ mother, paid for tens of thousands of dollars of renovations, and then allowed Thomas’ mother to continue living in the home under the guise that Crow was only interested in preserving the home for posterity. Another tip led to the discovery that Crow paid tuition at two private boarding schools for Thomas’ grandnephew. None of these transactions were disclosed by Thomas. For a summary of the issue, see Engelberg and Esinger (2023).

Chapter References

Akard, Patrick J. 1992. “Corporate Mobiilization and Political Power: The Transformation of US Economic Policy in the 1970s.” American Sociological Review 57:597-615

Alexander, Dan. 2019. “Inside the $400 Million Fortune of Trump’s Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin.” Forbes, July 22. https://www.forbes.com/sites/danalexander/2019/07/22/inside-the-400-million-fortune-of-trumps-treasury-secretary-steve-mnuchin/.

Archives Unbound: African American Studies. n.d. “Franklin D. Roosevelt and Race Relations, 1933-1945.” Archives Unbound: Primary Sources. https://www.gale.com/primary-sources/archives-unbound-african-american-studies.

Barley, Stephen R. 2010. “Building an Institutional Field to Corral a Government: A Case to Set an Agenda for Organization Studies.” Organization Studies 31 (6):777-805

Barnes & Thornburg. 2023. “Public Policy and Lobbying: Making an Impact.” https://btlaw.com/work/industries/government-and-public-finance/public-policy-and-lobbying.

Bean, Anderson. 2020. “Biden’s Corporate Cabinet: A Breakdown.” Rampart. https://rampantmag.com/2020/12/bidens-corporate-cabinet-a-breakdown/.

Bennett, Laurie. 2012. “Charles Koch: ‘We Are Committed to Seeing Cato Flourish’.” Forbes, March 8. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lauriebennett/2012/03/08/charles-koch-we-are-committed-to-seeing-cato-flourish/.

Burch, Philip. 1980. Elites in American History: The New Deal to the Carter Administration. Vol. 3. New York: Holms and Meier.

Bush, Daniel. 2018. “All of the Ways Scott Pruitt Changed Energy Policy.” PBS Newshour, July 5. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/all-of-the-ways-embattled-epa-chief-scott-pruitt-has-changed-energy-policy.

Business Roundtable. n.d. “About Us.” https://www.businessroundtable.org/about-us

Campaign Finance Institute. 2017. Number Political Action Committees Making Contributions to Candidates, 1976-2018.http://www.cfinst.org/pdf/vital/VitalStats_t9.pdf.

Chang, Alisa. 2013. “When Lobbyists Literally Write the Bill.” NPR: It’s All Politics, November 11. https://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2013/11/11/243973620/when-lobbyists-literally-write-the-bill.

Chumley, Cheryl K. 2020. “Democrats Aghast at Outing as Communists.” Washington Times, February 20. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2020/feb/20/democrats-aghast-outing-communists/

Crews, Clyde Wayne Jr. 2017. “How Many Federal Agencies Exist? We Can’t Drain the Swamp until We Know.” Forbes, July 5. https://www.forbes.com/sites/waynecrews/2017/07/05/how-many-federal-agencies-exist-we-cant-drain-the-swamp-until-we-know/.

Cruz, Liset, Ali Blanco, Megan Messerly, Abhinanda Bhattacharyya, and Anna Wiederkehr. 2025. “37 Ways Project 2025 Has Shown Up in Trump’s Executive Orders.” Politico. Feburary 5. https://www.politico.com/interactives/2025/trump-executive-orders-project-2025/

Dickson, Peter R., and Philippa K. Wells. 2001. “The Dubious Origins of the Sherman Antitrust Act: The Mouse That Roared.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 20 (1):3-14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30000640

Eismeier, Theodore J., and Philip H. Pollock III. 1986. “Politics and Markets: Corporate Money in American National Elections.” British Journal of Political Science 16 (3):287-309

Engelberg, Stephen, and Jesse Eisinger. 2023. “The Origins of Our Investigation into Clarence Thomas’ Relationship with Harlan Crow ” ProPublica, May 11. https://www.propublica.org/article/clarence-thomas-harlan-crow-investigation-origins.

EPA. 2023. “Clean Air Act Advisory Committee Caaac: Caaac Membership, August 9, 2021 – August 10, 2023 “. https://www.epa.gov/caaac/caaac-membership-august-9-2021-august-10-2023

Equal Justice Initiative. 2017. Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. 3rd ed. Montgomery: Equal Justice Initiative.

Ernsthausen, Jeff. 2023. “How the Ultrawealthy Use Private Foundations to Bank Millions in Tax Deductions While Giving the Public Little in Return ” ProPublica, July 26. https://www.propublica.org/article/how-private-nonprofits-ultrawealthy-tax-deductions-museums-foundation-art.

Ever-Hillstrom, Karl. 2022. “Top Lobbying Firms Report Record-Breaking 2021 Earnings ” The Hill, January 20. https://thehill.com/business-a-lobbying/business-a-lobbying/590709-top-lobbying-firms-report-record-breaking-2021/

Figueiredo, John M. de, and James J. Kim. 2004. “When Do Firms Hire Lobbyists? The Organization of Lobbying at the Federal Communications Commission.” NBER Working Paper Series (10533). https://www.nber.org/papers/w10553

Frantz, Elaine s. 2018. “The Homestead Strike and the Weakening of the First Us National Paramilitary System.” The Global South 12 (2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/globalsouth.12.2.03

Furlin, Alex. 2023. “Who Actually Writes Congressional Bills? Not The Leaders You Elected…”. GoodParty.org. July 7. https://goodparty.org/blog/article/who-actually-writes-congressional-bills-not-the-leaders-you-elected

Goertz, Gary, and James Mahoney. 2012. “Within-Case Versus Cross-Case Causal Analysis.” In A Tale of Two Cultures: Qualitative and Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences edited by Gary Goertz and James Mahoney, 88-100. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Harrington, Liz. 2019. “The Socialist ‘Squad’ Does Not Like America. Take It from Them.” Townhall, July 21. https://townhall.com/columnists/lizharrington/2019/07/21/the-socialist-squad-does-not-like-america-take-it-from-them-n2550365.

Heritage Foundation. 2010. The Heritage Foundation 2010 Annual Report; Solutions for America. Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation.

History.com Editors. 2021. “Militia Slaughters Strikers at Ludlow, Colorado.” HISTORY, April 19. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/militia-slaughters-strikers-at-ludlow-colorado.

Igielnik, Ruth. 2020. “70% of Americans Say U.S. Economic System Unfairly Favors the Powerful.” Pew Research Center, January 9. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/01/09/70-of-americans-say-u-s-economic-system-unfairly-favors-the-powerful/.

IRS. 2023. “Charities and Nonprofits: Lobbying.” https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/lobbying

Kagan, Julia. 2022. “Private Foundation: Meaning, Types, Examples.” Investopedia, April 24. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/privatefoundation.asp.

Katz, Alyssa. 2015. The Influence Machine : The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Corporate Capture of American Lif. New York: Spiegel & Grau.

Legal Information Institute. n.d. 29 U.S. Code § 157 – Right of Employees as to Organization, Collective Bargaining, Etc. .https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/29/157.

Lim, Timothy C. 2016. Doing Comparative Politics: An Introduction to Approaches and Issues. 3rd ed. Boulder: Lynne Reinner Publishers.

Lipton, Eric. 2014. A Closer Look at How Corporations Influence Congress. In Fresh Air. , edited by Terry Gross.https://www.npr.org/2014/02/13/276448190/a-closer-look-at-how-corporations-influence-congress.

Lipton, Eric. 2016. “How Think Tanks Amplify Corporate America’s Influence.” New York Times, August 7. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/08/us/politics/think-tanks-research-and-corporate-lobbying.html

Marcus, Josh. 2025. Trump Brands Zohran Mamdani a ‘100% Communist Lunatic’ Backed by ‘Dummies’ Who Has a ‘Grating’ Voice..” Independent, June 26. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/trump-zohran-mamdani-nyc-mayoral-candidate-b2777183.html

Markel, Howard. 2015. “Give ’Em Health, Harry.” The Milbank Quarterly 95 (1):1-7

Mintz, Beth. 1975. “The President’s Cabinet, 1891-1972: A Contribution to the Power Structure Debate.” Insurgent Sociologist 5 (3):131-148

National Association of Manufacturers. 2022. A Historical View of the Nam: Leadership in Support of the Values Underlying a Strong Manufacturing Sector and an Exceptional America: NAM.

NowThis. 2017. “Communism Vs. Socialism: What’s the Difference? (Youtube Video).” NowThis Originals, September 21. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrtDZ-LOXFw.

Office of Comptroller of the Currency. 2023. “Mutual Savings Association Advisory Committee.” accessed July 20, 2023 https://www.occ.gov/topics/supervision-and-examination/bank-management/mutual-savings-associations/mutual-savings-association-advisory-committee.html

OpenSecrets.org. 2023a. “Business, Labor & Ideological Split in Lobbying Data.” Open Secrets: Following the Money in Politics. https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/business-labor-ideological?cycle=2022

OpenSecrets.org. 2023b. “Lobbying Data Summary.” Open Secrete: Following the Money in Politics. https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying.