7 The Corporate Class and Race in American Foreign Policy

Introduction

In standard textbook discussions of US foreign policy and international relations more generally, there is typically scant or no discussion of corporate power or race/racism. (A definitional note: “Foreign policy,” as used in this chapter, is a catch-all phrase that refers to any policies made by the federal government that are designed to impact political-diplomatic, economic, or military-security relations with other countries. “International relations” refers more broadly to interactions between and among sovereign states.) The conventional wisdom has been that foreign policy is made by political or governmental actors, especially the president and key foreign policy and national security advisors, acting strictly in the interests of the country as a whole, as opposed to acting in the interests of a particular class or with any sort of racial bias. For example, if the US government—reflecting a decision made by the president, who is also the commander-in-chief—decides to launch an invasion of another country, which the US did in invading Iraq in 2003, the generally accepted and often unquestioned understanding is that the decision is premised on protecting the security and interests of the United States (i.e., “national security” and the “national interest”), which means protecting the American people from a serious or grave threat.

Importantly, in the mainstream media and academia, foreign policy decisions are most often couched in language that, whether intentionally or not, reinforces that understanding by using such phrases as, “The US decided to invade …”. While typically used as innocuous shorthand (I use it myself), such phrasing, when used repeatedly and digested in an unthinking manner, suggests that foreign policy decisions are not made by individual actors who may be representing, for instance, their own (class) interests and (racial) biases, but by an impersonal and monolithic state that simply, consistently, and surely acts in the interests of the American people.

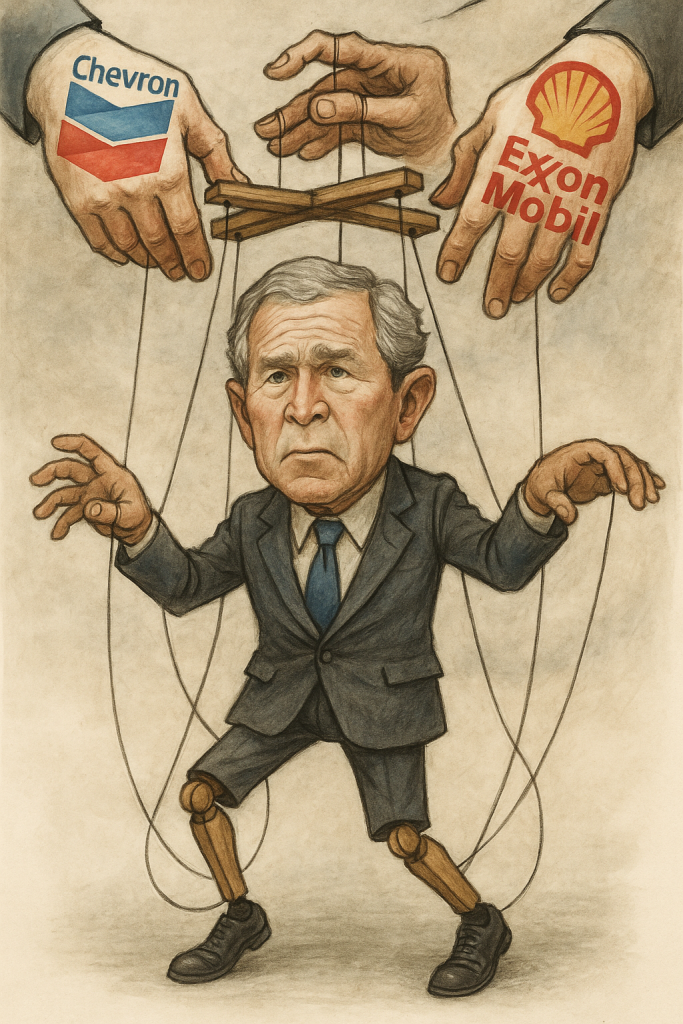

The conventional understanding of US foreign policy, however, has always been subject to challenge by scholars, political pundits, and skeptical members of the general public. While criticisms have come from both the left and the right, there is common thread that connects their views, namely, the idea that foreign policy decisions do not reflect the will of the American people but instead reflect the interests of some extraordinarily wealthy, behind-the-scenes puppet master or masters. For many conservatives, an oft-cited puppet master is/was George Soros, one of the 100 richest people on the planet and the founder of the Open Society Foundation. (Conservatives also use the term “globalist” to refer more generally to other, usually liberal elites.) A litany of old-school and more recent conservatives—e.g., Rush Limbaugh, Bill O’Reilly, Glen Beck, Elon Musk, Joe Rogan, and Ben Shapiro, to name a few—have asserted that Soros has been able exercise huge influence over US domestic and foreign policy, albeit only when Democrats are in charge. Rush Limbaugh (who passed away in 2021), for example, accused Soros of “pulling the marionette strings” of President Obama (cited in Silverstein 2018).

For liberals or progressives, the puppet masters are big business and the corporate class in general. Many on the left, to cite a case that will be examined in more detail later in this chapter, point to the decision by the Bush administration to invade Iraq in 2003. As they see it, the decision was fundamentally motivated by the interests of “Big Oil,” which wanted easier access to and control of Iraq’s invaluable oil reserves.

Singling out individuals for vilification, as conservatives have done with George Soros, is more about trying to create a useful bogeyman in order to smear the left and Democrats than it is serious analysis (although it certainly is the case that individuals in the corporate class can exercise outsized influence over government policy). This vilification of Soros is easy enough to see. He has been called a Nazi, an Antichrist, and a “multimillionaire Jew,” the latter of which is barely disguised antisemitic trope (cited in Vogel, Shane, and Kingsley 2018). It’s also telling that these commentators rarely, if ever, accuse wealthy conservatives of acting as puppet masters over Republican administrations.

At the risk of sounding biased, the left’s position, by contrast, is typically far more substantive but can also be overblown. In either case, though, it is important to understand that corporate class influence and racism are generally not obvious when it comes to foreign policy decisions, as they are so deeply embedded it difficult to see their effects even on close examination. But when you know what to look for and how to look, the task becomes much easier to accomplish. In this chapter, I will use the Class-Race-Power (CRP) framework to examine the foreign policy making process in the United States. The CRP framework, I should emphasize at the outset, does not explain every foreign policy decision. There are major and consequential foreign policy decisions that do not necessarily reflect the direct influence of the corporate class and/or embedded racism. In other words, for some and perhaps even many foreign policy decisions, national security and national interests may be guiding principles for decision makers. It is also very likely the case that, in perhaps the large majority of foreign policy decisions, there is a melding of corporate class influence, embedded racism, and national interests/security such that it becomes very difficult to disentangle their independent effects.

With all this in mind, in the next section, I will provide some basic theoretical or explanatory context for examining foreign policy and international relations. Understanding the theoretical context is important as it highlights core assumptions that many people unknowingly hold or agree with. This is especially important for people who rarely think about foreign policy, international affairs, or global issues, as it’s easy to accept arguments or claims put forward by others without giving a second thought to the underlying assumptions.

A Brief Theoretical Digression

The concept of a monolithic state (meaning, in simple terms, a state in which all key decision-makers and all relevant agencies are more or less on the same page when it comes to understanding, defining, and protecting the “national interest”) is most clearly reflected in an academic theory known as neorealism. (Important note. Students frequently mistake the discussion is this section as an endorsement of neorealism. This is decidedly not the case, as the following section will make clear. Please keep this point in mind.) This is a complicated and sophisticated theory, but it boils down to the proposition that the structure of the international system—which is made up of independent or sovereign states with no overarching centralized government (e.g., no “world government”)—compels state actor to behave in certain ways depending on their relative position in the international system. In other words, the international system is an anarchy and in an anarchic environment, individual states need to take care of themselves any way they can. To understand this, consider a country, such as Haiti (as of 2023), in which there is no effective national government. In that country individuals cannot look to the government for security, protection, or assistance. As a result, criminal gangs run rampant, fighting among themselves for control of resources and territory (Human Rights Watch 2023); it’s a Darwinian struggle for survival.

At the international level, the situation is similar, although not exactly the same, as states, to some extent, voluntarily abide by international laws, treaties, and norms. Still, in this scenario, states ultimately need to protect themselves and their interests since there is no world government capable of policing the behavior of individual states who decide to violate international laws, treaties, or norms. Because of the overriding requirement for “self-protection,” in the neorealist view, it doesn’t really matter who occupies the top decision-making positions in a country; they all end up making the same basic decisions in line with the size and military strength of the country they are leading. For the United States specifically, neorealism tells us that it doesn’t matter whether a Republican, Libertarian, Democrat, socialist, or anyone else is in charge. Their policy decisions, in essence, will be determined by the dynamics and imperatives of the international system, with national security always the prime objective. More to the point, for the purposes of this book, neorealist theory tells us that class is irrelevant and that the corporate class, no matter how powerful domestically, has no say when it comes to crucial foreign policy decisions.

To repeat: Neorealism tells us that it is irrational for political leaders to do anything else but to act in a manner that prioritizes national security and the national interest. After all, if they fail to do, in the dog-eat-dog, Darwinian world of international relations, they will put the entire country at risk. In this view, the only rational thing for leaders of the United States to do, when it comes to the issue of security, is invest massive amounts of money into building and maintaining the best equipped, best trained, most technologically advanced, and most powerful military in the world, lest other great powers close the military gap. Even if the US maintains a significant absolute military advantage over all other countries (which is certainly the case), if other countries—especially China and Russia—make relative gains vis-à-vis the US (such as increasing their military spending 5% one year while the US increases its military budget only 2%), that invites danger and heightens the threat to US national security and to all Americans. Anyone who disagrees with this view is being, well, “unrealistic,” idealistic, or naïve. (As the name implies, neorealism is rooted in an older theory simply referred to as realism, the latter of which was a theoretical response to the previously dominant theory referred to as idealism.)

Thus, while the vast majority of Americans are likely completely unfamiliar with neorealism as an academic theory, most Americans probably agree with its basic logic. Consider this: In a 2020 Gallup poll, 67% of respondents agreed that the US defense spending was either “about right” or “too little” (Jones 2020), which meant they agreed with the neorealist proposition that very large defense budget is needed for national security. That year, it is worth noting, US defense spending was $788 billion, which was three times more than China’s military budget of $252 billion, the next highest military spender (Da Silva, Tian, and Marksteiner 2021). Apparently, that wasn’t sufficient, as two years later, under President Biden, the Senate voted 83-11 to pass a record-setting $858 billion military spending bill (Zengerle 2022). Under Trump in 2026, defense spending is likely to increase to over $1 trillion (Olay 2025).

Problems with Neorealism or “Why Neorealism Isn’t Very Realistic”

Neorealism is a serious theory, which can and does offer important insights into relations and interactions between and among states. At the same time, it is ironically apolitical. I say “ironically” because, at a general level, neorealism is all about the struggle for power among sovereign states. But the struggle for power seems to disappear when it comes to considering what happens inside sovereign states. That might be reasonable if it was clear that internal political processes didn’t impact foreign policy decisions.

Yet, it is clear that states themselves are made up of various branches of government (typically the executive, legislative, and judicial) each of which has some authority over foreign policy and each of which might have different ideas about how to first define the national interest and security, and second, how to maximize American interests and security. Within the executive branch, moreover, there are dozens and even hundreds of different bureaucratic agencies each of which have their own domains or “turfs” they want to protect. As with the different branches, too, they do not necessarily see eye-to-eye on how to define and defend American interests and security. Equally important, despite what neorealism claims, states don’t exist in “splendid isolation” when it comes to the policy making process, whether foreign or domestic. State actors are part of a larger environment composed of ordinary citizens, political parties, media outlets, a multitude state and non-state organizations and agencies, various racial/ethnic groups, and social classes, the latter two of which are most important for the purposes of this chapter.

As previous chapters have made clear, class and race have had a profound impact on domestic policies in the United States. But if the corporate class exercises power over the domestic policy making process and if race/racism has had a deep effect on political dynamics in the United States, it stands to reason that such influence doesn’t stop “at the water’s edge,” that is, at the borders of the United States. I should emphasize that I’m not saying anything new here. As I noted above, the conventional (i.e., realist/neorealist) understanding of US foreign policy has always been subject to challenge.

Among scholars, the most sustained challenge comes from those who specialize in the study of US foreign policy (as opposed to international relations). They have long argued that “domestic politics,” which refers to political struggles inside government and over government policy, plays a central role influencing foreign policy (for one relatively recent example, see Milner and Tingley 2015). However, except for some attention paid to interest groups, these “domestic politics approaches” to US foreign policy (which fall into a larger category of “Foreign Policy Analysis” or FPA) have not paid nearly as much attention to the corporate class or to race/racism.[1] In the next section, I will pay attention to class and race beginning with a look back to middle of the 20th century, with two foundational foreign policy decisions, the Marshall Plan and Bretton Woods.

Setting the Stage: American Foreign Policy and Corporate Class Power in the Early Postwar Period

The Marshall Plan

Following the end of World War 2, as I noted in Chapter 2, the US had achieved a hegemonic position in the so-called “Free World” (i.e., all allied countries with market-based economies, many of which were democratic but many others of which were decidedly unfree dictatorships). While there is a strong tendency to define hegemony in terms of military dominance, an even more important element is economic dominance. Economic dominance didn’t just mean that the US economy had substantially higher GDP than all other market-based economies at the time; much more importantly, it meant that American corporations were more productive, more efficient, and more technologically advanced, by a wide margin, than everyone else in the world. This obviously meant that US companies were, as a whole, far more competitive than foreign firms anywhere in the world.

The very dominance of American firms, however, meant that, to ensure their continued prosperity, it was necessary to expand beyond the US market. American policy makers didn’t have to be convinced of this through lobbying or direct pressure from the corporate class; instead, they implicitly understood that American hegemony hinged on creating a world in which American firms had plenty of room to expand and grow. On this point, remember that large corporations in the US have long had a great deal of structural power. This encouraged political leaders to prioritize the interests of those large corporations on an ongoing basis.

It was in this larger context that arguably, as one scholar put it, “the most innovative piece of foreign policy in American history” was born in 1948 (McCormick 1995): The Marshall Plan, also known by its formal name, the European Recovery Act (ECA), was named after George C. Marshall, who served as Secretary of State during the administration of Harry S. Truman (1945-1953). The ECA can be described as foreign aid package to aid in Europe’s recovery from the war. But it was much more than that. Rather than just handing money to European allies for rebuilding as they saw fit, Marshall and other key figures in the administration required a quid pro quo.

One requirement, according to McCormick, was that European countries agree to take a major step toward creating a single, integrated transnational European market, which US policy makers thought was necessary if their economies, as a whole, were not only going to survive, but also thrive. The Truman administration, in short, wanted to help Europe become a more productive and eventually more competitive center of capitalism. On the surface, this makes no sense. After all, why would the administration, still less the corporate class, want to create more competition for American firms? The answer is simple. American firms were essentially too strong for their own good. That is, in the immediate postwar period, they effortlessly dominated European markets, which meant that there was such a huge commercial imbalance between the US and its major trading partners that Europeans literally could not earn enough foreign exchange (i.e., US dollars) to pay for the goods and services they needed from the United States (this was referred to as the “Dollar Gap” crisis).

To get the Marshall Plan approved, though, the Truman administration needed buy-in, not just from Congress, but from the corporate class, and to lesser extent, from organized labor. According to McCormick, buy-in from big business was particularly important and, to this end, the administration offered to let big business share power in carrying out the reconstruction of Europe. A whole new bureaucratic agency was established, the Economic Cooperation Administration, which was “dominated by corporate executives active in world trade” (82). Secure in the knowledge that their interests would be protected and prioritized in the Marshall Plan, the corporate class became cheerleaders for the program as they actively and enthusiastically lobbied both Congress and the American public for its passage.

Meanwhile, buy-in from organized labor may not have been essential, but it nonetheless useful. Recall that President Truman replaced FDR and, thus, maintaining a strong connection with labor was considered to be fairly important for the administration. This said, parts of organized labor readily or eventually agreed with the logic underlying the Marshall Plan, but a small segment of “radical critics,” to use McCormick’s language, could not be convinced. They had to be “purged,” although this wasn’t done at the urging of administration; rather, “one of the reasons labor’s center-right wing was willing to excise its left wing … was a desire to enhance the legitimacy of labor unions in the public eye” (McCormick, 84).

Keep in mind that this was a period during which the now pro-big business Republican Party was working hard to defeat organized labor, which included associating organized labor with the communist movement. “Demonstrations of labor’s own anticommunism”, then, “was one way to prevent more antilabor legislation …” (ibid.). All of this reflects a profoundly political process at the domestic level, which cannot be disassociated from the passage of, not just “the most innovative piece of foreign policy in American history,” but also the “greatest achievement of the Federal Government from the end World War II until the beginning of the 21st century,” at least according to a survey of 450 historians and political scientists (Nessen and Dews 2016).

Building a New Global Financial System: Bretton Woods and the Corporate Class

The Marshall Plan was developed and implemented at time when American hegemony was on the rise. It was easy for politicians, the corporate class, organized labor, and the American public to be mostly on the same page as seemingly everyone was benefiting from America’s predominant position in the world—of course, that wasn’t the case for important segments of the US population. But it was a particularly good time for the American corporate class, for which the world was, as the old saying goes, their oyster. At the domestic level, the corporate class was still concerned about organized labor and its political allies, especially the Democratic Party (the “liberal-labor alliance”), but at the international level, as I’ve already noted, the government was hard at work—often without any prodding (or lobbying) by big business—reshaping the world to the direct benefit of the corporate class. Even still, power and politics still mattered, and the corporate class made sure it was at the table for every major foreign policy decision that could impact its interests.

This was the case in the negotiations over a foreign policy program that was perhaps even more momentous than the Marshall Plan, namely, the establishment of new international monetary order known as the Bretton Woods system (named after the New Hampshire location where international negotiations involving 44 countries were held in 1944). While the Bretton Woods system was the brainchild of American and British officials (two key architects were Harry Dexter White, the chief international economist at the US Treasury Department and John Maynard Keynes, a famous economist and advisor to the British Treasury), the American corporate class was involved in building the framework for this new system from the beginning.

As Ronald Cox and Daniel Skidmore-Hess (1999) explain it, the Bretton Woods system was initially envisioned by American corporate and political elites “as a transition from British global hegemony to U.S. global hegemony” (27). This segued to the establishment of a coalition of US government officials and a “bloc of internationalist firms,” led by two early corporate-funded think tanks, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR)[2] and the Committee for Economic Development. Together the two think tanks “represented a group of capital-intensive investors who either had a stake in the Western European markets or hoped to expand their investments in the region.” The corporate investors included a who’s who list of prominent corporations: Standard Oil, General Motors, General Electric, ITT, Pan American Airlines, Westinghouse, General Mills, Bristol-Myers, Chase National Bank, among others (47).

A key element of Bretton Woods system—i.e., a set of unified rules and policies governing currency exchange rates—did not last. Thus, it’s common to hear about the “collapse of the Bretton Woods system.” (Cox and Skidmore-Hess also argue that the collapse of the system was due, in no small measure, to corporate lobbying as the monetary framework became less and less beneficial to US corporate interests.) However, two key elements of the negotiations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, not only survive to this day, but arguably have come to play an indispensable role in maintaining stability in the global economy.

Very briefly put, the IMF was designed, among other things, to be a “lender of last resort” by providing short-term loans to countries experiencing serious economic difficulties. The World Bank, by contrast, was originally designed to provide longer term financing for developmental or infrastructure projects—the first recipients were Western European countries recovering from World War 2. The broader goals of the two organizations (sometimes referred to as the Bretton Woods Institutions or BWIs) were to provide greater stability in the global economy, encourage more trade among market-based economies, and promote the growth of global markets (or of capitalism more generally). In the early years, decision making in both organizations was completely dominated by the United States and western countries more generally. This has led to a great deal of criticism, as both organizations have been accused of using access to loans to force mostly poorer countries to open their domestic markets to western capital and firms, ostensibly for the good of the poorer countries themselves but, according to the critics, actually for the benefit of American and other western firms.[3]

Importantly, according to Cox and Skidmore-Hess (1999), the US corporate class exercised significant influence over the creation of the World Bank in particular. As they explained it:

Industrialists … secured guarantees from the State and Treasury Departments that the World Bank would not displace private investors in their funding of long-term, low interest projects. U.S. commercial and investment bankers were concerned about the potential inflationary aspect s such lending but were reassured by the fact that leaders of the back would be drawn from the U.S. Banking establishment. State Department officials assure the New York investment Bankers Association, an early critic of capital controls and the potential expansionary impact of the Bretton Woods Monetary Agreements, that the World Bank would work closely with Wall Street in making securities and bonds available for purchase by private investors (47).

The claim that the corporate class not only had a seat at the table but also a very strong and effective voice in shaping two of the most important foreign policy decisions in the early postwar period is meant to support the argument that corporate influence doesn’t magically stop at the water’s edge. Still, some dyed-in-the-wool neorealists/realists might argue that foreign economic policy is not the same as national security policy. From their perspective, it may be reasonable for the corporate class to have a say in policies that impact their interests, but on issues of direct national security, there is little to no room for non-state actors to play a role. In fact, in the past, realists and neorealists argued that there is a clear-cut distinction between “high politics” and “low politics.”

High politics refers to matters directly related to national security, where the survival of the country is at stake. Low politics, once used in somewhat disdainful manner by realists and neorealists, refers to ostensibly less vital domains of foreign policy, such as trade and economic affairs or participation in international organizations dealing with global health, the global climate, immigration, labor regimes, and so on.[4] The distinction helped to maintain the fiction that foreign policy was driven by monolithic state actors. However, it was always an arbitrary distinction, as the line between national security policy and foreign economic policy, in particular, has always been blurred if not completely absent. One of the easier ways to see how blurred the line is, and has long been, is to consider the quintessential national security issue (from a Neorealist standpoint), namely, war.

Wars, Capitalism, and the Corporate Class

Have US administrations waged war as result of direct or even indirect pressure or lobbying by the corporate class? The answer, almost certainly, is “No.” Have US administrations waged wars for reasons that have little or nothing to do with direct or even indirect military/security threats to the United States? The answer to this second question is an emphatic “Yes.” More to the point, have US administrations waged war for primarily economic reasons, the most important of which is ensuring that American corporations have access to important markets around the world? For this third question, the answer, while perhaps a little less emphatic, is also “Yes.”

Actually, it doesn’t take much work to find evidence that US administrations, without provocation (although usually with fake provocation), have decided to send tens of thousands and even millions of ordinary Americans to fight in wars against supposed enemies who posed absolutely no military or security threat to the United States. One important example is the Vietnam War, in which 58,220 Americans, mostly very young men, died and 75,000 were severely disabled, out of the more than 2.6 million uniformed soldiers sent to serve in the war (between 40% and 60% of this number either fought in combat or were regularly exposed to attack).

The Vietnam War: A War for Capitalism and the Corporate Class

The Vietnam War has a tremendously complicated history and, in a few paragraphs, it’s only possible for me to barely scratch the surface. Keeping this caveat in mind, the war is typically understood as a struggle against communism. Vietnam was, in this regard, largely unimportant in its own right; it was, as President Lyndon B. Johnson once said, just a “little nation” in a faraway region that most Americans, at the time, had probably never heard of. However, if Vietnam fell, so the reasoning went, other countries in the region would also fall to communism and that would be, as President Dwight Eisenhower told a conference of governors, “… of the most terrible significance to the United States.” Why? As Eisenhower further explained it, “If Indochina [the old name for Vietnam] goes, several things happen right away. The Malay Peninsula, that last little bit of land hanging on down there, would be scarcely defensible.” One by one, he warned, other countries in the region—Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines—would be toppled thereby directly threatening the security and safety of the United States (cited in Glass 2017).

Eisenhower’s reasoning reflects what is known as the domino principle. I should add, at the time, Eisenhower was not advocating that the US go to war in Vietnam; instead, he was attempting to justify providing $400 million in aid to France for its war against those Vietnamese, who were, it is important to add, fighting for independence against French colonial rule, which began in 1887, and which the French had tried to reimpose after the end of World War 2 (the French colonial government was temporarily displaced by the Japanese during the war). Significantly it was not only Eisenhower who used this reasoning to justify US involvement in Vietnam, so did all of his immediate successors: John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon.

Still, none of this explains how the Vietnam War was not primarily fought to ensure American national security. After all, wasn’t communism not only a threat to the very survival of all Americans but also to all of the “free world”? In retrospect, the answer is clearly no. We know because, while the “communists” won the war in Vietnam, none of the “dominoes” fell; even more, the communist party leadership in Vietnam ultimately decided on its own, in 1986 (a little more than a decade after the end of the war), to abandon its centrally planned command economy and embrace a market-based economy, essentially deciding to voluntarily join the capitalist world (for more discussion, see Path 2020). Very importantly, this tells us that the domino principle had no objective basis; instead, it was simply an idea—although, remember, “ideas matter”—that various administrations embraced, which raises the question: Where did the idea of falling dominoes come from?

It is difficult to pin down the precise origins of the following dominoes idea; however, it is clear that from the 1940s onward, the corporate class, largely through the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) was closely associated with key foreign policy decision makers in various US administrations. On this point, it is worth noting that several high-level government officials were former directors of the CFR and had the ear of various presidents. One of these as W. Averell Harriman, President Truman’s director of mutual security (he was also part of the corporate class, having served as chairman of the board of the Union Pacific Railroad Company from 1932-1946). As early as 1945, Harriman argued that Southeast Asia (which included Vietnam) was a vital strategic location, primarily because of its vast resources of “tin, rubber, and numerous other strategic materials” (Shoup and Minter 1977, 234). Significantly, he also wrote that the “loss of this area to the free world would have the most serious consequences for the security of the United States” (ibid.), a phrase almost repeated verbatim by Eisenhower about a decade later. Harriman’s idea was subsequently adopted by Truman’s National Security Council (NSC), which included another CFR member, Dean Acheson—a former lawyer for the elite, upper-class law firm, Covington & Burling LLP.

Importantly, Eisenhower not only echoed Harriman’s view that the “loss of Indochina” would have serious consequences for American security, but he also echoed Harriman’s point that the danger was not a military one, but was instead an essentially economic one, i.e., access to raw materials such a tin, tungsten, rubber, and the like. Consider this: In response to a reporter’s question about the strategic importance of Vietnam (Indochina) in 1954, Eisenhower first noted that Indochina is a very important source of tin and tungsten, then added, “when we come to the possible sequence of events, the loss of Indochina, of Burma, of Thailand, of the Peninsula, and Indonesia following, now you begin to talk about areas that not only multiply the disadvantages that you would suffer through loss of materials, sources of materials, but now you are talking really about millions and millions and millions of people” (emphasis added; Eisenhower 1960).

In short, the war was all about economic “materials.” One could make an argument, of course, that access to vital raw materials is a core national security issue. Yet, while Southeast Asia was a main source of tin, tungsten, and rubber, sending more than 2.6 million soldiers to secure this access—especially since it wasn’t clear this access would ever be cut off—seems like a massive and irrational overreaction.

So, there must have been another reason why Southeast Asia was so important in the eyes of US policy makers at the time. Actually, there was a much larger economic reason for fighting the war in Vietnam. It is a reason that has been almost completely ignored after the 1950s, but which Eisenhower clearly spelled out in his reply to the reporter. Continuing, he stated, “the geographical position achieved [through the ‘falling dominoes’] … does many things. It turns the so-called island defensive chain of Japan, Formosa [Taiwan], of the Philippines and to the southward; it moves in to threaten Australia and New Zealand. It takes away, in its economic aspects, that region that Japan must have as a trading area or Japan, in turn, will have only one place in the world to go—that is, toward the Communist areas in order to live” (emphasis added; ibid.).

To be clear, Eisenhower’s logic was that the communists in Vietnam needed to be defeated in order to save “Japan’s trading area.” (It is worth noting that Eisenhower brought several CFR leaders and members into his administration, including John Foster Dulles as director of the CIA; Eisenhower himself had been an active member of the Council.)

This raises obvious question: Why was protecting Japan’s trading area vital to US national security? For the vast majority of Americans, it wasn’t. But for key segments of the US corporate class (whose interests were directly represented in and by the CFR), it was understood that Japan’s revival as a center of capitalism in Asia was essential for future growth and expansion. Highly productive American firms are always in need of growing, accessible, and profitable markets. As I’ve argued, this was reflected in the Marshall Plan and the Bretton Woods system, and, so it appears, was equally reflected in the Vietnam War. On this point, it important to understand that, in 1949, the unthinkable happened when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) defeated the Nationalist and pro-US forces in China.

The “loss of China” removed a huge potential market for American business, and American policy makers and the corporate class seemed determined to not lose any more. Eisenhower, in the same his press conference referenced above, put it bluntly after citing the loss of 450 million Chinese to the CCP: “We simply can’t afford greater losses” (emphasis added; ibid.). My translation: “We cannot afford to lose another vast and still untapped market for America’s corporate class.” Eventually, the US administration fabricated an attack against US forces in the Gulf of Tonkin, which led to the Gulf of Tonkin resolution passed by the US Congress in 1964. This gave President Lyndon B. Johnson the authority to deploy conventional US forces (as opposed to covert forces and advisors) to Vietnam and begin a period of open warfare against North Vietnam.

War, Class, and Race: Making War Possible

In most discussions of the Vietnam war, race is barely mentioned. And when it is mentioned, it is most often connected to racial relations inside the United States. One reason for this is clear: The dominant national security narrative (whether based on military or economic security), leaves no room for race as even a minor factor in the decision making process. This was also the case in the more specific falling dominoes narrative, which utterly disregarded the history and humanity of the people of Vietnam and Southeast Asia more generally.

The slaughter of “little brown people,” as Nixon once said of America’s South Vietnamese allies (in reference to the possibility of unilaterally withdrawing from the war), “wouldn’t have been too bad … nobody would have cared” (cited in Little 2022). This disregard of and near-complete disdain for people of color—for all intents and purposes, not seeing them as human beings whose lives are as valuable as the lives of white people—was and is much easier for privileged, white male decision makers in the US and other Western countries, who have long divided the world into different, unequal, and inherently inferior racial and ethnic groups. It also been an all too common theme of American policy in Asia, where racist assumptions about Asians have always played a role, albeit often implicitly but also explicitly, in the decision making process. This point is clearly reflected in America’s first protracted war against an Asian people, the Philippine-American War (1899-1902).

America’s Race War in the Philippines

In the smallest of nutshells, the war began after the defeat of Spain in the Spanish-American War. Spain had ruled the Philippines for more than 300 years and, with the defeat of Spain, the US took control of its former colony. Filipino independence fighters, who had been fighting against Spain for years, declared independence after the Spanish defeat, but President McKinley rejected this declaration and instead announced that the US would exercise control over the country through a policy of “benevolent assimilation.” Importantly, the takeover and subsequent war faced fierce resistance inside the United States among Americans opposed to imperialism. An American Anti-Imperialist League was formed, which grew into a mass movement that drew support from across the political spectrum and from prominent figures such as Mark Twain.

Thus, the US government had to legitimize its policy; a key strategy, according to Kramer (2006) was to racialize the war. Filipinos were portrayed as savages or barbarians, who were not yet capable of forming a true unified nation, suggesting that they were incapable of governing themselves and, thus, it was the responsibility—the “burden” of the white man—to do it for them. This idea was made explicit by the British writer Rudyard Kipling, who urged Americans, in 1899, to “take up the White Man’s Burden,” in an effort to persuade the US government to join the “imperial club” (Van Ells 1995). (The poem was originally written to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897; however, Kipling later revised it specifically to encourage Americans to support the effort to control the Philippines.)

The view that Filipinos were incapable of self-governance was reinforced in official reports, much of which relied on the “expertise” of an American zoologist, Dean C. Worchester, who had done some research in the Philippines in the 1880s. Not surprisingly, as Van Ells put it, “Worcester’s perceptions of the Philippine people reflected classic American notions of white supremacy. He [Worchester] noted, for example, the ‘childlike’ nature of Filipinos, as well as their ‘oriental’ traits such as deceit and treachery …”. In Worchester’s “expert” view, moreover, the Philippines was broken up into over 80 ethnic tribes, including a “wooly headed, black, savage dwarf” tribe, who he later removed from the human category altogether (611).

A second aspect of the administration’s racializing strategy was to define the “U.S. population as ‘Anglo-Saxons’ whose overseas conquests were legitimated by racial-historical ties to the British Empire” (185). Continuing, Kramer writes:

Specifically, the war’s advocates subsumed U.S. history within longer, racial trajectories of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ history which folded together U.S. and British imperial histories. The Philippine-American War, then, was a natural extension of Western conquest, and both taken together were the organic expression of the desires, capacities, and destinies of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ peoples. Americans, as Anglo-Saxons, shared Britons’ racial genius for empire-building, a genius which they must exercise for the greater glory of the ‘race’ and to advance ‘civilization’ in general” (ibid.).

The highly racialized legitimizing strategy helped the McKinley administration build the case for the war and subsequent takeover of the country. To be sure, it wasn’t the cause of the war, but it played a key role in legitimizing an imperialistic war, on the part of the US, over a people who clearly had an expressed desire for political independence that, in itself, presented absolutely no danger to the United States. Indeed, it’s likely that, if the US had fully supported Filipino independence from the start, relations between the two countries might have been very strong and hundreds of thousands of lives would have not been lost, including over 220,000 Filipinos (the vast majority of whom were civilians) and 4,300 American soldiers.

Race and Wars of Choice

The upshot is this: While race/racism may not be a cause of war, it can make war possible. This is because wars, specifically those that are not provoked by a direct attack against the United States (i.e., “wars of choice”), need justification. This is particularly the case when wars of choice are fought to protect and promote the interests of the corporate class, even if only indirectly, and of capitalism more generally, which was the case in Vietnam and was also likely the case in the Philippines—in the Philippines, the original goal of the McKinley administration was only to acquire and control coaling stations on the island. He was later convinced by a team of Republican senators and others that a “commercial port in the Philippines would enhance American trade markets in the Orient, then deemed ‘limitless” or ‘illimitable.’” The senators also argued that control of the Philippines would “provide extra profits” to agriculture and industry (Coletta 1961, 345).

Those who pursue wars of choice understand that waging war to enrich the corporate class or expand markets, will not be supported by a large part of the population, especially ordinary citizens who obliged to actually fight and potentially die in the wars. The fusion of class and race in American society, however, makes it possible for wars of choice to be seen as wars of necessity.

In justifying intervention in Vietnam, blatant racism and white supremacy was not readily apparent. Instead, the threat of communism was used as the primary rationale (Herring 2004). But, as is evidenced in Nixon’s quote about “little brown people,” it is fairly clear that American leaders did place much if any value on the value of “Oriental” lives, a point that became vividly clear once the war began. As General William Westmoreland, commander of US forces in Vietnam, famously said, “The Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does the Westerner. Life is plentiful, life is cheap in the Orient” (cited in Turse 2013). Of course, dehumanization of the “enemy,” regardless of race/racism, is the rule, not the exception—it’s something that all countries do. But the racist construction of the world by the United States, in which the needs and interests of white peoples and countries are always prioritized, likely play a role in defining some peoples as enemies even before the first shot is fired.

Consider this: North Vietnamese leader, Ho Chi Minh, wrote a letter to President Truman in 1946, in which he “earnestly appeal[ed]” to the president and the American people to support the Vietnamese struggle for independence “in keeping with the principles of the Atlantic and San Francisco Charters” (Digital Public Library of America 1946). (One of the principles of the Atlantic Charter [click here to read full text], which was the result of a meeting between FDR and his British counterpart, Winston Churchill, was to support the restoration of self-government and the right of people to choose their own form of government, as well as for countries to abandon the use of force.) Clearly, there was an opportunity for the US government to work toward a peaceful resolution, which could have served the national interests of Vietnam and the United States and saved millions of lives from death, grievous physical injury, and mental anguish. Yet, the Truman administration—the same one that decided to drop not just one, but two, nuclear bombs on a largely civilian population in Japan killing more than 240,000 human beings in total and 120,000 in the blink of an eye—apparently did not give Ho Chi Minh’s appeal a second thought.

Class, Race, and Power in the Invasion of Iraq

The Philippine-American and Vietnam wars were a long time ago. While it’s certainly possible that the dynamics of class, race, and power have changed significantly since then, that does not appear to be the case. A more recent case—albeit one that is still not completely fresh—is the decision by the administration of George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003, another “war of choice.” This war was framed by the administration of George W. Bush as necessary to protect the US from a dire, even existential, security threat. Here’s how Bush himself justified the invasion: “[Iraq] possesses and produces chemical and biological weapons. It is seeking nuclear weapons…. Members of Congress of both political parties, and members of the United Nations Security Council, agree that Saddam Hussein is a threat to peace and must disarm. We agree that the Iraqi dictator must not be permitted to threaten America and the world with horrible poisons and diseases and gases and atomic weapons” (cited in Pan 2005).

There was one huge problem with Bush’s statement: Following an exhaustive 18-month investigation, the CIA concluded that the Iraq regime didn’t have any chemical and biological weapons and did not have an active nuclear weapons program (Datta 2005). Nor did Iraq have anything to do with the 9-11 attack, which was also part of the administration’s narrative.[5] In retrospect, it reasonably certain that the administration unashamedly lied to the American public or, at the very least, grossly exaggerated the threat in order to “sell the war” (Isikoff and Corn 2007). It is also fair to say that, when an administration intentionally and repeatedly lies in order to convince the public and Congress that a war is necessary, it means the war wasn’t, in fact, necessary.

The lies, though, were extremely effective, especially since the administration was already aware that the American public was primed for war against Iraq. In January 2022, just before the Bush government began its campaign to sell the war, it was clear that Americans would support a war against Iraq if they learned that country aided in the terrorists on 9/11 (83%) or if Iraq had nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons (77%) (Doherty and Kiley 2023). Taking no chances, the Bush administration decided to use both reasons, and by October of that same year, it had successfully convinced 66% of the American public of the unequivocal falsehood that Iraq aided the 9/11 terrorist attacks against the US (ibid.). The efforts to “prove” the Iraqi regime had nuclear weapons, too, ramped up as Secretary of State Colin Powell appeared before the UN Security Council to make the (made up) case against Iraq. “My colleagues,” he convincingly asserted, “every statement I make today is backed up by sources, solid sources. These are not assertions. What we’re giving you are facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence” (cited in Schwarz 2018). Powell, to reiterate, was lying.

Not everyone was taken in by the Bush Administration’s mendacious attempts to justify the war. Writing before the invasion began, a group of writers for the Monthly Review (2003), an “independent socialist magazine,” first noted that experts from the International Atomic Energy Agency and the UN weapons inspections body had already determined that Iraq’s biological weapons’ facility had been “destroyed and rendered harmless,” and that the country’s nuclear stocks were gone, as were long-range missile systems.

In short, it was very apparent to the group at the Monthly Review that Iraq posed no military threat to the US, still less the entire world. But if there was no imminent (or even prospective) national security threat, why did the Bush administration decide to attack Iraq? According to the writers, the invasion was, first and foremost, designed to further the interests of major American oil companies. The authors argue that, following the imposition of sanctions on Iraq after the end of the Gulf War in 1991, it was impossible to expand Iraqi oil production.

Given the fact Iraqi oil reserves were valued at several trillion dollars at the time, this was a major impediment to US oil profits. Even more, it became clear that major competitors in Russia, France, and China were trying to loosen sanctions so that they could finalize deals they had already made with Iraq, valued at $1.1 trillion—in 2002, oil reserves in Iraq were estimated to be 112 billion barrels, the second largest in the world, while the country also had 110 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (Longley 2021). A US-led invasion would automatically nullify all these deals, while presumably giving US oil companies an inside track to making new deals. “Given this logic,” according to authors:

… it is hardly surprising that Bush and his cabinet were planning the invasion of Iraq even before he came to office in January 2001. The plan was drawn up by a right-wing think tank for Dick Cheney, now vice president, Donald Rumsfeld, defense secretary, Paul Wolfowitz, Rumsfeld’s deputy, Bush’s younger brother Jeb Bush, and Lewis Libby, Cheney’s chief of staff (Research Unit for Political Economy 2003).

While there still is some serious debate on whether the war was the product of Big Oil’s direct power and influence,[6] it is enough to say that “Big Oil,” in the first place, pushed hard to elect George W. Bush—who was personally tied to the oil industry, as was his vice president Dick Cheney—and Big Oil got exactly what it wanted in terms of their electoral victory. Moreover, it is clear that the Bush administration had a very close relationship with the largest oil companies as his administration received more campaign contributions from Big Oil than any other administration in history (Palmer 2008). It is also clear that Bush’s most influential advisors were members of the corporate class. In particular, Dick Cheney (vice president) was a former chair of the board and CEO of Halliburton, as major energy company, as well as a board member and director of the CFR; and Donald Rumsfeld (Secretary of Defense), was chair and CEO of General Instruments.

Cheney’s views on the need to for the US to exert influence over the Middle East were obvious. Speaking in 1999 in at lunch gathering for the London Institute of Petroleum, Cheney said, “By 2010 we will need on the order of an additional fifty million barrels a day. So where is the oil going to come from? . . . While many regions of the world offer great oil opportunities, the Middle East with two thirds of the world’s oil and the lowest cost, is still where the prize ultimately lies” (cited in Nell and Semler 2007, 562). Tellingly, too, during the invasion, the only Iraqi ministry that was protected by US troops, both during and after the invasion, was the Iraq Oil Ministry. In addition, in order provide a greater semblance of international legitimacy to the invasion, the UK government, under Tony Blair, was persuaded to support the American effort. At the time, it was an extremely unpopular decision within the UK, so it was puzzling that the Blair government went along. But there was clearly a quid pro quid. As Nell and Semler (2007) put it, “the poodle was being fed; the UK was put in charge of Basra, and BP [British Petroleum] would be allowed to negotiate for a Production Sharing Agreement. France and Russia on the other hand were excluded, and their existing contracts would not be honoured” (571).

Whither Race?

It is fair to say that the decision to invade Iraq, even if not done in the interests of or at the behest of Big Oil specifically, was largely motivated by economic factors, which benefited the corporate class far more than it did the American people. But does this mean that race/racism was irrelevant? A superficial level, it is easy to make that argument. Again, though, if we consider how race/racism makes war possible, the central role of race comes into sharp focus. To see this, it’s necessary to begin our analysis well before the start of the Iraq War, with Western efforts to dominate the Middle East more generally. These efforts, or project, began shortly after the discovery of large reserves of oil in the region in the early 1900s. While western countries could and did rely on brute military force to take control of foreign lands, longer term projects of domination typically require ideological justification.

Thus, just as racism legitimized slavery, racism legitimized colonialism. Edward Said (1978) created a special name for the ideological project of Western colonial powers, “Orientalism.” His argument, while subject to a great deal of criticism and controversy, has also been widely embraced. One author, Hsu-Ming Teo (2013), summarized the basic points from Said’s argument as follows:

To Said, Orientalism was much more than false or negative images about the Orient. It was a process by which the West deliberately ‘Orientalised’ the Orient or made the region seem ‘Oriental’, representing it in such a way that a dizzying heterogeneity of countries, cultures, customs, peoples, religions and histories were incorporated into the Western-created category, ‘Oriental’, and characterised by their exotic difference from and inferiority to the West. Orientalism permitted Westerners to make sweeping negative generalisations about, for instance, ‘the Oriental character’, ‘the Muslim mind’ or ‘Arab society’, subsuming all differences into a monolithic and racialising fantasy (emphasis added, 2).

While Orientalism became the ideological basis for western, mainly European, colonial rule prior to the discovery of large oil deposits in the Middle East, it served as an almost automatic justification for the western decision to, for all intents and purposes, declare the resources in the Middle East to be theirs for the taking. After all, in the Orientalist narrative, the “Orient” (a nebulous term that primarily focused on the Middle East, North Africa, but also included Southeast and East Asia) was a place of violence, cruelty, corruption, despotism, primitivism, and cultural stagnation; it was a region “outside the progressive march of historical development” (Teo 2013, 10). As such, to white western leaders, the people of that region didn’t “deserve” to control or even benefit from the invaluable resources that just happened to be under their feet.

Americans, in general, accepted this powerful narrative or discourse, which provided the framework for systematic efforts by US administrations, on behalf of the corporate class, to exercise dominion over the Middle East. It is easy to dismiss discourse as powerful, but it’s important to understand that discourse (and ideas) always precede action; everything people decide to do is informed by the ideas they hold. To appreciate this, consider how an alternative discourse, if genuinely embraced, would have essentially prevented US administrations from presuming it had a right to use force to control the energy resources of the Middle East.

Ironically, one alternative discourse came from FDR’s administration itself, which helped craft the Atlantic Charter of 1941. Some of the principles of the Atlantic Charter were mentioned above, but it’s worth taking another look. Among the eight principles agreed to in the Charter were that countries: not seek aggrandizement, territorial or otherwise; not ignore the freely expressed wishes of the people; endeavor to respect the right of all states, “great or small, victor or vanquished,” to access, on equal terms, the trade and raw materials of the world; and to abandon the use of force (for full text, see Avalon Project 2008). To be sure, these were mere “words on paper” that were completely ignored. But recall that the US Constitution is also just words on paper.

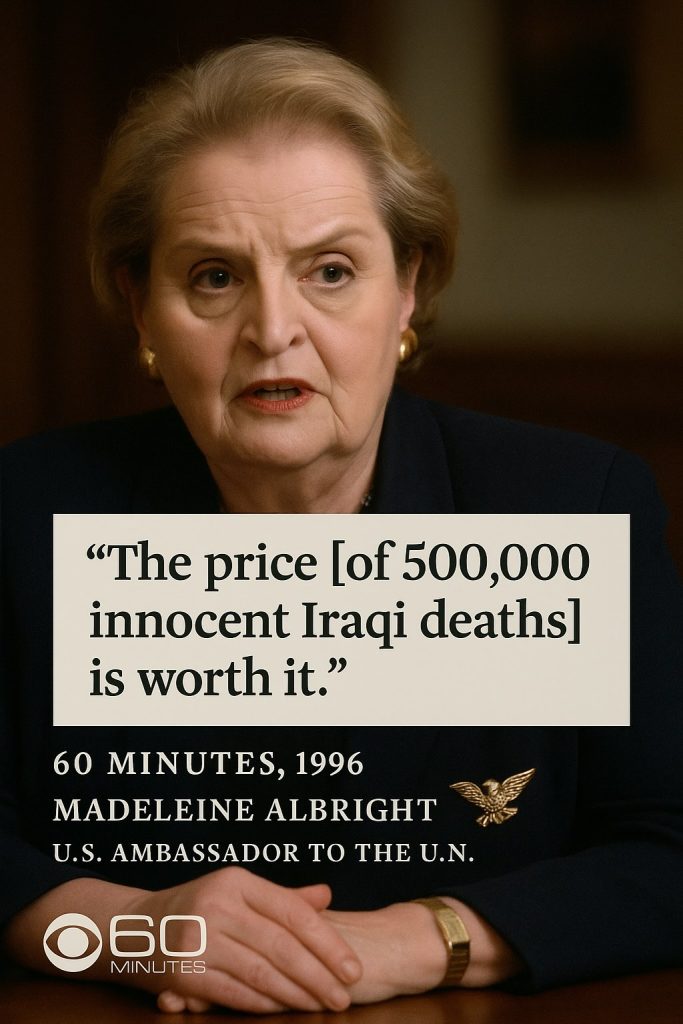

It is important to understand that the Orientalist narrative or discourse does not stand alone; instead, as with any dominant discourse, it is deeply embedded everywhere societies—in government policies and practices, in popular entertainment and media, in educational systems, in the military, in the “justice” system, and so on. It becomes a seemingly natural part of the (socially) constructed reality in which people exist. In this sense, General Westmoreland’s quip should be turned around and rephrased to read: “The white man doesn’t put the same high price on ‘Oriental’ life as he does the lives of other white people. White life is beautiful, ‘Oriental’ life is cheap for us.”

While my rephrasing may sound hyperbolic and even offensive, consider what Madeline Albright, Secretary of State in the Clinton administration, said in response to question asked by Lesley Stahl in a 60 Minutes interview in 1996. Referring to a UN report that highlighted the deadly effects of US (and international) sanctions on Iraq after the end of the 1991 Gulf War, Stahl first said, “We have heard that half a million [Iraqi] children have died. I mean, that is more children than died in Hiroshima.” Stahl then asked, “And, you know, is the price worth it?” Albright’s answer was clear and simple: “I think that is a very hard choice, but the price, we think, the price is worth it” (cited in Twaij 2022). There really could be no purer statement from an American policy maker that “Oriental life” is extremely “cheap.” Albright later offered a qualified “apology” in her 2003 memoir, where she wrote, “Nothing matters more than the lives of innocent people,” while insisting the deaths of innocent children was the fault of the Iraqi regime. It was, as one critic put it, a “disingenuous” apology (Richman 2003).

To sum up, there was no compelling national security interest to invade Iraq. The country posed no threat to the United States, near term or long term. Indeed, after years of strict and crippling economic sanctions, the country’s military was far weaker in 2002 than it was in 1990. In that first conflict, Iraq proved to be absolutely no match for the US-led coalition. Iraqi military resistance crumbled in a matter of days. Yet, a very large segment of the American population readily bought into the lie that Iraq, about a decade later, was an even greater threat. There is good reason to believe this was because the Orientalist narrative had become so deeply ingrained in American society that simply asserting, in an authoritative manner and with few fake “facts,” that the Iraqi regime was a mortal danger was enough. If this meant hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths, well, that was a “cheap” price to pay for “America’s peace of mind” and, of course, corporate profits.[7]

Conclusion

This chapter has focused on “big” (and admittedly mostly dated) foreign policy decisions, which may seem to be a very unbalanced discussion. However, in principle, the bigger the (foreign policy) issue, the more national security or the national interests should trump parochial or narrower interests, especially the economic interests of the corporate class. In other words, if class and race are clearly entwined in the most momentous foreign policy decisions, then it’s very likely they play an important role in less momentous and everyday foreign policy decisions.

Still, it’s not unreasonable to argue that the “economic interests of the corporate class” are largely the same as the interests of the entire country. This is reflected in well-known but often misquoted statement by Charles Wilson, the president of General Motors, who was being questioned in a confirmation hearing, in 1953, to become Secretary of Defense for Dwight D. Eisenhower. Wilson was asked if he would sell his GM stockholdings to avoid a conflict of interest. His answer was that he hadn’t foreseen any problem because, as he put it, “ … for years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa” (cited in Patterson 2013). While his sentiment may be true in some cases, it is fair to say that the Philippine-American war, the Vietnam War, the Iraq War, and dozens of other conflicts and interventions—including covert CIA operations to help overthrow democratically elected governments in Iran in 1953[8] and Chile in 1973[9]—may have been good for the corporate class, but they were not good for the “American people.” This is obviously and especially true for the tens of thousands of ordinary Americans who fought and died in wars and the many more who suffered physical and mental anguish, as well as family members who were affected by the death and anguish of their loved ones.

Chapter Notes

[1] For example, in one fairly popular book on “foreign policy analysis” (a framework that incorporates the domestic politics approach), there is not a single mention of corporations, interest groups, lobbying, firms, or business in the index. See Hudson (2007). As for race/racism, it is also difficult to find sustained analysis is the foreign policy literature, although there are exceptions. One particularly noteworthy one is by Michael H. Hunt, Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy (2009).

[2] There is some debate over the role that the CFR has played in shaping US foreign policy. To some analysts, the CFR has played a central and defining role (for example, see Domhoff 2013), while to others, the role has been more limited as the CFR has been portrayed primarily as a neutral civic group deeply concerned about US foreign relations, but one that is not strongly connected to either the government or to the corporate class (see Silk and Silk 1980). It is abundantly clear, though, as Philip Burch points out, that almost all of the men who have served as president of the Council, throughout the early postwar years (at least until 1980), had important corporate directorship ties (Burch 1981).

[3] One early and well known critic of the IMF and World Bank is Susan George (1999) who argued that the two BWIs, but especially the IMF, use the debt of poor countries as an “efficient tool.” The market-based reforms forced upon these countries may look good on paper, but they necessarily lead to dozens of poor countries trying to sell the same good to the same limited markets. It’s a recipe for economic ruin, which has exacerbated poverty and instability in most poor countries rather than solving it. For a summary of the main criticisms of the IMF and World Bank, see Bretton Woods Project (2019).

[4] Other scholas make a different distinction by defining high politics as any policies dealing with interactions between and among states, while low politics is defined as politics that occur within states (i.e., domestic politics). See Olsen (2017).

[5] According to Bruce Riedel (2021), who was in the Bush administration as a staff member of the National Security Council, “The Bush administration was eager to mobilize the anguish of the 9/11 attack to support the war.” It didn’t matter, however, that the intelligence community had already come to the “unequivocal conclusion that Iraq had nothing to do with either 9/11 or al-Qaida.”

[6] One meticulously researched counterargument is by Muhammad Idrees Ahmad (2014), who argues that the war was primarily pushed by Israel, which was able to convince key members of the Bush administration, especially those already sympathetic to Israel, that the war was necessary. Importantly, even if Ahmad is correct—and he directly challenges the Big Oil thesis—it is still the case that this momentous foreign policy decision did not reflect US national interests.

[7] Civilian Iraqi deaths from the war are estimated to be somewhere between 187,000 and 210,000, based on research by the website Iraq Body Count (https://www.iraqbodycount.org/)

[8] For a brief summary of this event, see Wu (2018).

[9] For a discussion of the overthrow of Salvador Allende, see Kornbluh and Bock (2020)

Chapter References

Ahmad, Muhammad Idrees. 2014. The Road to Iraq: The Making of a Neoconservative War Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Albright, Medeleine K. 2003. Madam Secretary – A Memoir. New York: MacMillan.

Avalon Project. 2008. “Atlantic Charter.” The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/atlantic.asp.

Bretton Woods Project. 2019. “What Are the Main Criticisms of the World Bank and IMF?” Inside the Institutions, January 1. https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2019/06/what-are-the-main-criticisms-of-the-world-bank-and-the-imf/.

Burch, Philip H. Jr. 1981. “Review: The American Establishment. By Leonard Silk and Mark Silk.” American Political Science Review 75 (2):512-513. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/abs/american-establishment-by-leonard-silk-and-mark-silk-new-york-basic-books-1980-pp-xi-351-1395/8F307ACD6373249B96F460CBEE88BF8A

Coletta, Paolo E. 1961. “Mckinley, the Peace Negotiations, and the Acquisition of the Philippines.” Pacific Historical Review 30 (4):341-350

Cox, Ronald W., and Daniel Skidmore-Hess. 1999. U.S. Politics and the Global Economy : Corporate Power, Conservative Shift. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Da Silva, Diego Lopes, Nan Tian, and Alexandra Marksteiner. 2021. “Trends in World Military Spendings, 2020.” SIPRI Fact Sheet, April. https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/fs_2104_milex_0.pdf.

Datta, Arko. 2005. “Cia’s Final Report: No Wmd Found in Iraq.” NBC News, April 25. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna7634313.

Digital Public Library of America. 1946. “A Letter from Ho Chi Minh to Harry Truman in 1946 Regarding the US Involvement in Vietnamese Independence from France.” February 28. https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/declaration-of-the-rights-of-man-and-of-the-citizen/sources/899.

Doherty, Carroll, and Jocelyn Kiley. 2023. “A Look Back at How Fear and False Beliefs Bolstered U.S. Public Support for War in Iraq.” Pew Research Center, March 14. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/03/14/a-look-back-at-how-fear-and-false-beliefs-bolstered-u-s-public-support-for-war-in-iraq/.

Domhoff, G. William. 2013. “Why and How the Corporate Rich and the Cfr Reshaped the Global Economy after World War Ii.” Who Rules America?, October, (Website). https://whorulesamerica.ucsc.edu/power/postwar_foreign_policy.html.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. 1960. “Dwight D. Eisenhower: 1954 Containing the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President, January 1 to December 31, 1954.” In The Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

George, Susan. 1999. A Fate Worse Than Debt. New York: Grove Weidenfeld.

Glass, Andrew. 2017. “Eisenhower Invokes ‘Domino Theory,’ Aug. 4, 1953 ” Politico, August 4. https://www.politico.com/story/2017/08/04/eisenhower-invokes-domino-theory-aug-4-1953-241222.

Herring, George C. 2004. “The Cold War and Vietnam.” OAH Magazine of History 18 (5):18-21

Hudson, Valerie M. 2007. Foreign Policy Analysis: Classic and Contemporary Theory. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Human Rights Watch. 2023. World Report 2023: Events of 2022. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Hunt, Michael H. 2009. Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Isikoff, Michael, and David Corn. 2007. Hubris: The inside Story of Spin, Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Jones, Jeffrey M. . 2020. “Record High Say U.S. Defense Spending Is ‘About Right’.” Gallup, March 16. https://news.gallup.com/poll/288761/record-high-say-defense-spending-right.aspx.

Kornbluh, Peter, and Savannah Bock. 2020. “Allende and Chile: ‘Bring Him Down’.” National Security Archive: Briefing Book 3732, November 3. https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/chile/2020-11-06/allende-inauguration-50th-anniversary.

Kramer, Paul A. 2006. “Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire: The Philippine-American War as Race War.” Diplomatic History 30 (2):169-210

Little, Becky. 2022. “7 Revealing Nixon Quotes from His Secret Tapes.” History.com, June 15. https://www.history.com/news/nixon-secret-tapes-quotes-scandal-watergate.

Longley, Robert. 2021. “Did Oil Drive the US Invasion of Iraq? .” ThoughtCo., October 4. https://www.thoughtco.com/oil-drive-us-invasion-of-iraq-3968261.

McCormick, Thomas J. 1995. America’s Half-Century: United States Foreign Policy in the Cold War and After. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Milner, Helen V., and Dustin Tingley. 2015. Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Nell, Edward, and Willi Semler. 2007. “The Iraq War and the World Oil Economy.” Constellations 14 (4):557-585

Nessen, Ron, and Fred Dews. 2016. “Brookings’s Role in the Marshall Plan.” Brookings, August 24. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/brookings-role-marshall-plan/.

Olay, Matthew. 2025. “Senior Officials Outline President’s Proposed FY26 Defense Budget.” DOD News, June 26. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/4227847/senior-officials-outline-presidents-proposed-fy26-defense-budget/

Olsen, Nathan. 2017. “Blurring the Distinction between ‘High’ and ‘Low’ Politics in International Relations Theory: Drifting Players in the Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Relations and Diplomacy 5 (10):637-642

Palmer, Mark J. 2008. “Oil and the Bush Administration.” Earth Island Journal, March. https://earthisland.org/journal/index.php/magazine/entry/oil_and_the_bush_administration/.

Pan, Esther. 2005. “Iraq: Justifying the War.” Council of Foreign Relations, February 2. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/iraq-justifying-war.

Path, Kosal. 2020. “The Origins and Evolution of Vietnam’s Doi Moi Foreign Policy of 1986.” TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 8 (2):171-185

Patterson, Robert W. 2013. “‘What’s Good for America . . .’.” National Review, July 1. https://www.nationalreview.com/2013/07/whats-good-america-robert-w-patterson/.

Research Unit for Political Economy. 2003. “Behind the War on Iraq.” Monthly Review 55 (1). https://monthlyreviewarchives.org/index.php/mr/article/view/MR-055-01-2003-05_3

Richman, Sheldon. 2003. “Albright ‘Apologizes’.” The Future of Freedom Foundation (FFF), November 7. https://www.fff.org/explore-freedom/article/albright-apologizes/

Riedel, Bruce. 2021. “9/11 and Iraq: The Making of a Tragedy.” Brookings, September 17. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/9-11-and-iraq-the-making-of-a-tragedy/.

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Schwarz, Jon. 2018. “Lie after Lie: What Colin Powerll Knew About Iraq 15 Years Ago and What He Told the U.N.” The Intercept, February 6. https://theintercept.com/2018/02/06/lie-after-lie-what-colin-powell-knew-about-iraq-fifteen-years-ago-and-what-he-told-the-un/.

Shoup, Laurence, and William Minter. 1977. Imperial Brain Trust. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Silk, Leonard, and Mark Silk. 1980. The American Establishment. New York: Basic Books.

Silverstein, Jason. 2018. “Who Is George Soros and Why Is He Blamed in So Many Right-Wing Conspiracy Theories?” CBS News, October 24. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/who-is-george-soros-and-why-is-he-blamed-in-every-right-wing-conspiracy-theory/.

Teo, Hsu-Ming. 2013. “Orientalism: An Overview.” Australian Humanities Review 54 (5):1-20

Turse, Nick. 2013. “For America, Life Was Cheap in Vietnam.” New York Times, October 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/10/opinion/for-america-life-was-cheap-in-vietnam.html.

Twaij, Ahmed. 2022. “Let’s Remember Madeleine Albright for Who She Really Was.” Aljazeera, March 25. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2022/3/25/lets-remember-madeleine-albright-as-who-she-really-was.

Van Ells, Mark D. 1995. “Assuming the White Man’s Burden: The Seizure of the Philippines, 1898-1902.” Philippine Studies 43 (4):607-622

Vogel, Kenneth P., Scott Shane, and Patrick Kingsley. 2018. “How Vilification of George Soros Moved from the Fringes to the Mainstream.” New York Times, October 31. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/31/us/politics/george-soros-bombs-trump.html.

Wu, Judy. 2018. “What Makes a Good War Story? Absences of Empire, Race, and Gender in the Vietnam War.” Diplomatic History 42 (3):416-442

Zengerle, Patricia. 2022. “U.S. Senate Passes Record $858 Billion Defense Act, Sending Bill to Biden.” Reuters, December 15. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-senate-backs-record-858-billion-defense-bill-voting-continues-2022-12-16/.