4 Race, Class, and American Exceptionalism

Introduction: Race and American Exceptionalism

For at least four decades, scholars, pundits, politicians, and the general public have accepted the idea of American exceptionalism. Being “exceptional,” of course, sounds like a very positive thing. Who wouldn’t want to be exceptional? And, for the most part, the general or popular understanding of the phrase “American exceptionalism” is that the United States is exceptionally great politically, socially, culturally, technologically, educationally, economically, militarily, and so on. There are certainly many exceptional—defined as unusual, atypical, or deviating from the norm—aspects of the US. Some of these exceptional aspects have been commented upon for centuries. In fact, the idea goes as far back as 1630, long before there was a United States, when John Winthrop, one of the leading figures in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, wrote, “We shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us”[1] (cited in Pease 2018). As Donald Pease (2018) writes, though, “American exceptionalism was more decisively shaped by the ideals of the European Enlightenment.”

More specifically, “The founders imagined the United States as an unprecedentedly free, new nation based on founding documents—the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—that announced its unique destiny to become the champion of the universal rights of all humankind.” To the extent that most Americans think about the idea of American exceptionalism, it is likely the foregoing description is what they have in mind, whether or not they agree with it—speaking of which, a 2019 survey indicates that a majority of Americans do, in fact, think the US is exceptional (60.4%), but a large percentage, almost 40%, consider the US to be “just another country acting in its own interests” (Eurasia Group Foundation 2019).

There are other dimensions to the idea of American exceptionalism. In particular, in the eyes of some observers, the United States is also exceptional because (1) class distinctions are fluid, meaning that it is relatively easy to move up from one class to another; and (2) class conflict, to the extent it exists, is relatively minor compared to other industrialized democracies, especially those in Europe. One can even find references to the US as a classless society. However, if you recall the discussion in Chapter 3, the notion that class conflict in the US has been minor clearly isn’t true. As for class mobility, the “lower classes” of most OECD countries have an easier time moving up than their American counterparts (Rank and Eppard 2021).

Be that as it may, there has long been a commonly held belief in the US that all Americans are “born equal,” which suggests that class status is, at most, transitory and surmountable, at least in principle. This image of a country where class is largely irrelevant or even absent dates back more than a century. Back in 1906, Werner Sombart, a prominent German academic and one-time socialist posed the question, “Why is there no socialism in the United States?”[2] Part of his answer was that, in contrast to workers in Europe at the time, the typical American worker “loves capitalism” to the extent that he “devotes his entire body and soul to it” (Sombart 1979 [reprint]). Underlying this (deeply problematic) assertion, too, was Sombart’s belief that, in the US, “bowing and scraping before the ‘upper classes,’ which produced such an unpleasant impression in Europe, is completely unknown” (cited in Reeves 2014).

More importantly, for the purposes of this chapter, Sombart dismissed race as having much to do with the exceptionalism of American workers and, by extension, with class dynamics in the United States. Sombart’s logic was clear, although not necessarily sound: In his view, since a good deal of America’s population at the time (the late 1800s and early 1900s) were from countries where “Socialism flourishes”—e.g., Germany, Russia, Poland, and Ireland—it was evident, to him at least, that the lack of socialist sentiment or, perhaps more accurately, class consciousness on the part of ordinary workers, in the US could not be due to race. As he unequivocally put it, “In explaining the circumstances of interest to us, we must therefore exclude any argument based on racial membership.”

Sombart’s analysis, of course, could be considered a profoundly ethnocentric relic of the past, if only because his view of race seems to have been limited to white European peoples as he made only passing mention of the Black population and slavery, and no mention at all of Native Americans or immigrants from Asian countries. Even so, it is fair to say that race has never been a significant or even minor part of the American exceptionalism narrative. (National narratives are part of almost all countries; they are typically part of the nation-building process and are as much myth as they are fact.) In important ways, though, race/racism is precisely what makes America exceptional, specifically with respect to class dynamics and, more generally, to American politics and democracy.

To be sure, race/racism has played and continues to play a role in virtually every peer democracy, including those without a history of slavery and with very little ethnic and racial diversity (e.g., Japan and South Korea). Nonetheless, as I just noted, its role in the US is arguably exceptional. To understand this, it is necessary to move beyond the somewhat trite and very general assertion (which I’ve admittedly used earlier in this book), that race has permeated all aspects of American life since the country’s founding. Moving beyond the trite and general to the meaningful and specific requires, most basically, an understanding of how slavery is directly responsible, to a significant extent, for a deep and perhaps the deepest political division in American society, a division that exists, albeit in different forms and with different dynamics over time, till this day. Not surprisingly, this deep division is originally between the slave-owning states of the South and the other states of the union. More specifically, it is a division that has driven and defined party politics in this country for most of its history.

The Deep Significance of Race in America’s Party System

As in all democracies, political parties occupy a central and defining position. It is perhaps not too much to say that democratic politics around the world revolve around parties and party dynamics. In addition, in all democracies, political parties represent different constituencies with different interests, priorities, and (usually) ideologies. In this regard, the US is no different from any other democracy, whether a peer democracy or not. (Remember that a core element in the definition of democracy used in this book is the existence of a competitive multiparty system.) It makes sense, then, to begin with a discussion on the deep significance of race in American politics with a focus on the party system in the United States.

To begin, it’s necessary to understand that attitudes toward slavery played a significant role in party dynamics from the very beginning of the republic, although in the very early years, there was not a lot of serious debate over slavery as the major political parties tended to be on the same page. By the late 1830s, though, this gradually began to change as a small but determined group of abolitionists, as Corey Brooks (2016) writes, “had become fed up with the two major parties, the Whigs [which became the Republican Party] and Democrats.

Both parties [until that point had] systematically downplayed slavery, opting instead to spar over seemingly unrelated issues including taxation, trade policy, banking and infrastructure spending.” As Brooks further explains, the abolitionists waged a fierce political struggle against the two dominant parties, which also involved forming their own antislavery third parties (the Liberty Party, 1840 to 1848; and the Free Soil Party, 1848 to 1854). This constant pressure over two decades, combined with the questions of whether new western territories would become slave states and how to deal with runaway slaves, ultimately led to the downfall of the Whig Party. The Whig party wasn’t completely dissolved; instead, it was reconstituted in a sense, as most of the Free Soil Party, a majority of Whig members from northern states, followers of the American Party (the “Know-Nothings”), and a substantial number of northern Democrats came together to form the Republican Party, which famously became the “Party of Lincoln.” Significantly, “[t]he one policy goal that united all Republicans was opposition to the expansion of slavery” (ibid.).

The Democratic Party, however, remained determinedly proslavery, especially since many those members who had been opposed to or at least conflicted about slavery fled to the newly formed Republican Party. To make a very long, very complicated, and much debated story short and simple, the conflict over slavery—which was the most important political issue of that time—came to head when the Southern states attempted to secede from the United States after the election of Abraham Lincoln. Of course, this then led to the bloody Civil War between the Republican-dominated northern states and the Democratic-dominated southern states. Following the end of the Civil War, slavery was abolished, at least on paper. (In Texas, it took more than two years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation to end, as federal troops had to be sent into Texas to enforce the Proclamation. This is the reason for Juneteenth, which commemorates the day the last group of enslaved people found out they had been freed [Martin 2025].)

The Republican Party also took steps to extend civil rights to former slaves: In 1866—about 100 years before the more well-known Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed—the country’s first Civil Rights Act was enacted, which provided a clear definition of US citizenship and affirmed that all citizens are equally protected by the law. This law was later constitutionally buttressed by the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, which granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including formerly enslaved people and also guaranteed, again on paper, “equal protection of the laws” (for a discussion of the relationship between the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the 14th Amendment, see Lash 2018). Note. Significantly, during the first days of his second term, President Trump signed an executive order declaring an end to birthright citizenship. While the Supreme Court has not yet directly ruled on the constitutionality of such an order, in June 2025, it gave the Trump administration a temporary victory by preventing lower courts from issuing nationwide injunctions. In practical terms, this means individual states can temporarily enforce the order to end birthright citizenship.

“White Identity Politics,” v. 1.0

In this context, it became much less likely, albeit not completely,[3] for white workers in the South to identify strongly with the Republican Party. The word “identify” is important to highlight for it points to a related and very important implication of race/racism in American politics, which is how it has shaped, from a very early stage, the sense of identity among different groups in American society. To put it simply, slavery set the stage for white Americans, regardless of their social or class status, to see themselves as inherently different from and superior to the “Black race.”

The end of slavery did not fundamentally change this view—it may have even reinforced it—at least for a large portion of white workers, not just in the South but in the northern states as well. That is, once former slaves became ordinary workers—putting them into the exact same class as white workers—it became all the more important for white workers to hold onto or to double down on their “whiteness.” David Roediger (2018) provides the reasoning: White workers needed to define themselves not only by their identity as workers but also by their identity as whites, wherein whiteness itself functioned as a “wage” (cited in Harris and Rivera-Burgos 2021). Actually, this argument originated from the writings of W.E.B. Dubois, born in 1868, who was the first Black American to earn a doctorate (at Harvard University); he later became a professor at Atlanta University and was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Dubois argued that, in the context of the late 19th century South,[4] the potential for transracial solidarity between Black and white workers was short-circuited by the emotional or affective benefits of whiteness; he referred to this as a “psychological wage.”

Interestingly, the same logic was also applied to recently arrived immigrant workers, including those from countries now matter-of-factly considered white, such as Italy, reflecting, very starkly, the social construction of race. Italian immigrants, one scholar notes, were sometimes “marked as black” in the late 1800s and early 1900s, especially when they “fraternized with local blacks … intermarried and when—like blacks—they supported Republican and Populist candidates instead of the party of white supremacy [i.e., the Democratic Party]” (Johnson 1999). In other words, at least for a short time, even the “white” working class was divided along ethnic and socially constructed racial lines.

The main point is this: Slavery and the end of slavery set in motion a political dynamic in the American party system that was propelled by race as much as, and sometimes more than, by class. Even Sombart (1979 [reprint]), who was mentioned earlier, recognized this, as he passingly acknowledged that “race” (this time referring to Black Americans) played a role in structuring the US political system. As he bluntly put it, “The Negro [sic] question has directly removed any class character from each of the two parties” (cited in Harris and Rivera-Burgos 2021).

All of this would just be a nice history lesson if, at some point, race ceased to play a defining role in both party and class dynamics in the United States. Indeed, one might argue that this was the case from the 1930s to the 1960s, as discussed in the previous chapter, when the (white) lower income and middle classes (the wage earning class). demonstrated a strong and, for a short time, remarkably high level of unity behind the Democratic Party, and when the party actually represented the interests of these classes. By this point, too, immigrants from Italy, Greece, Poland, Hungary, and other European countries, had become increasingly accepted as white, which helped to significantly expand the size of the white wage earning class—between 1886 and 1925, upwards of 13 million immigrants came to the US from southern, eastern, and central Europe (Starkey 2017).

An important aside. Over the decades following the end of the Civil War to the early 1930s, the Democratic Party and Republican Party gradually “switched places,” such that the Democratic Party evolved into a party representing the wage earning class more generally, while the Republican Party became more centered around the interests of big business or the corporate class. (For a brief discussion, see Box 4.1 Switching Places.)

Box 4.1 Switching Places: The Post-Civil War Evolution of the Republican and Democratic Parties

It is important to note that, despite its association with the South and the racist policies of the Jim Crow era following the Civil War, the Democratic Party had, by the late 1920s, significantly broadened its national appeal. This was partly due to the scramble to appeal to western voters in the post-Civil War era when new states in the West were added to the Union. This meant lots of new voters and both parties made efforts to win western voters over. The Democratic Party strategy was to promise providing federally funded social programs and benefits centered on the interests of the general population over big business (Wolchover 2022). The shift toward became more strongly pronounced when a Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson, took office in 1913 and, with a Democratic congressional majority, was able to pass a raft of legislation that was “devoted in various ways to the cause of social justice” (Rauchway 2010)

At the same time, there was a shift in the priorities of the Republican Party, which had become the party of big business revolving around northern industrialists, many of whom profited immensely from the Civil War and its aftermath. Even more, while initially pushing for civil rights legislation for former slaves—which required a strong federal role—the Republican Party fairly quickly gave up on these efforts and instead pushed for “smaller government,” especially when it came to the government’s role in the economy. When the Great Depression hit, then, the stage was set for a much stronger and broader shift to the Democratic Party. Although it would still take several more decades for the South to make a general switch to the Republican Party—which will also be discussed in this chapter—the Democratic Party under FDR began to look much like the Democratic Party of today.

Solid white support for a political party responsive to the needs of the wage earning class did, by itself, make a big political difference in the United States. Keep in mind, though, that the racial category of white was fluid. Italian immigrants, as I just mentioned, were once “marked as Black” in part because those eligible to vote tended to vote for the Republican Party. In fact, Italian American support for the Republican Party was quite strong until the late 1920s. But between 1924 and 1928, Italian Americans, especially those living in urban areas, switched en masse to the Democratic Party.

An analysis by Stefano Luconi (2001) shows that support for the Democratic Party among Italian Americans, in large cities, rose from a minuscule 3% to 57% in Philadelphia, from 6% to 69% in Pittsburgh, from 31% to 63% in Chicago, from 42% to 94% in Boston’s North End, from 43% to 93% in East Boston, and from 48% to 77% in New York City. Much of this new-found support was motivated by a desire to support an Italian American (and Irish on his mother’s side) candidate, Al Smith, who ran for president as a Democrat in 1928. In mining and mill towns, Lucino also notes, “support” for the Republican Party by Italian Americans remained strong, but much of this was likely due to coercive pressure placed on them by employers. Once the Great Depression hit, which led to large-scale job losses in these non-urban areas, however, Italian American laborers throughout the country began to support the Democratic Party. Thus, even within the “white vote,” race played a role.

FDR’s New Deal policies, it’s important to highlight, also attracted, for the first time, a large number Black voters to the Democratic Party (at least those who are able to get through the many voting roadblocks placed in front of them, especially in the Jim Crow South). Thus, for a time (at the height of FDR’s popularity in 1936), there was an odd coalition of voters: white southerners, Black Americans, “newly white” immigrants and other minority groups, northern city dwellers, westerners, and others. It is safe to say that the primary motivation behind this collection of strange bedfellows was economic fear. As Glenn Feldman put it:

The New Deal (and its vaunted coalition) was not so much American politics at normality but an aberration in which economic conditions were so terrifying, so oppressive, and so unprecedented, at least in the United States, that people (including white southerners) were willing to temporarily subsume traditional racial and cultural concerns to immediate class imperatives. They were willing to suppress a rampant and deep-rooted individualistic impulse—and more important, the mythology that surrounded it—to supplicate for public aid, lobby for state activism, and tolerate collective action (Feldman 2013, xii).

“White Identity Politics,” v. 2.0

Importantly, Feldman goes on to argue that the New Deal coalition was too heterogeneous and so variegated that it could not last. In retrospect, Feldman’s assumption seems to hold water; however, once brought together by economic exigency and fear, the possibility of a maintaining a trans-racial and trans-regional coalition of the lower income class, at the very least, was plausible given the gains they had made during this period of political influence. After all, the members of the coalition all shared one overwhelming economic interest. Moreover, given the efforts by the corporate class to reassert control over the political process by building an organized network, albeit one that didn’t start to fully emerge until the 1970s, but which nonetheless was taking shape (as I discussed in the previous chapter) as early as the 1940s, the class-based economic imperative certainly didn’t disappear

Indeed, if class interest was the only or most important factor at play, then it stands to reason that regardless of their racial or ethnocultural backgrounds or the regions in which they were from, workers in the lower income class across the United States would have clearly understood the power of staying unified as the most efficacious method to pursue their class interests. But that clearly wasn’t the case. And a basic reason, while subject to some debate, is equally clear: Namely, race/racism played a central and perhaps the central role in the dissolution of the “New Deal coalition,” and specifically, in the South’s crucial shift away from the Democratic Party toward the Republican Party.[5]

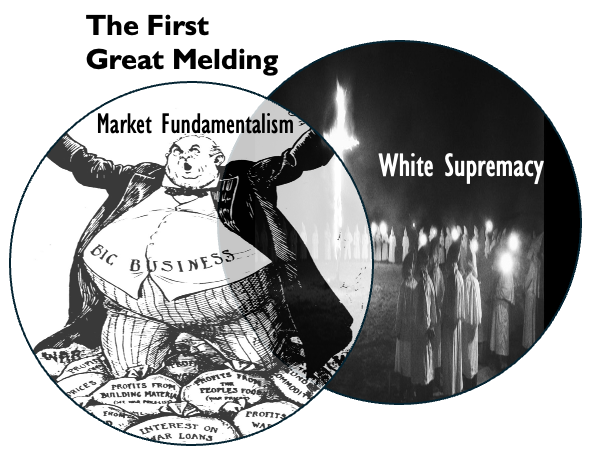

The South’s general shift to the Republican Party, which was subject to contestation within the South (meaning that the switch was not automatic), is important to highlight if only because it provides the clearest view on the essential role of race. On this point, I’ll return to and rely on Feldman’s analysis (2013), who has studied the issue in-depth from his position at the University of Alabama. As he explains it, there was a possibility of “biracial cooperation between working-class whites and blacks” (xiii), which the economic elite (planters and industrialists) in the South understood as a serious threat to their class interests. This led to, in Feldman’s words, the “first Great Melding,” which fused, on one side, economic conservatism (or market fundamentalism) and antipathy toward the federal government, with, on the other side, “the sacred cow of white supremacy” (ibid.). This great melding didn’t just happen; instead, it was the product of intentional action, instigated by the economic elite (i.e., corporate class), as they reacted to the “racial liberalism of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal.”

The first great melding, which Feldman describes as ingenious and brilliant, “allowed the besieged forces of wealth, privilege, extreme laissez-faire, and even a kind of state-sponsored corporatism to re-cast their affinity for economically rightist fundamentalism as something indissolubly bound to the holiest of cultural holies: white supremacy.” In doing so, Feldman continues, it created a huge (socially constructed) barrier for white workers in the South to make and sustain common cause with Black or other minority workers, since they could not be economic progressives (i.e., advocates of the sort of policies that labor unions generally support) and “right on race” (i.e., white supremacist) at the same time. In this new narrative, to put the issues as plainly as possible, no white Democrat could be a “true southerner.”

Feldman also discusses the second Great Melding, which unfolded at the same time as the first Great Melding and revolved around merging market fundamentalism—which, I will belatedly note, is the idea that a “free market” not only produces the best economic results but also produces the best societal results[6]–with religious fundamentalism.

In Feldman’s analysis, the melding of market and religious fundamentalism also took place on a shared platform of antidemocratic values, although the antipathy to democracy is not evident on first glance. But as Feldman explained it, “Just below the surface of both the neoliberal economic creed [i.e., market fundamentalism] and fundamentalist religion—clothed by constant paeans to freedom, liberty, and the individual—lay a dark, powerful, and pungent dislike of democracy.”

Not surprisingly, this dislike of democracy revolved around the ability of Black Americans and other “undesirables” to vote. Continuing, Feldman says, “Both economic and religious fundamentalists wanted people to vote— only they wanted ‘their kind’ of people to vote not members of the indiscriminate masses. Frequent attempts to narrow voter registration, make it more difficult for minorities to vote, or outright attempts to confuse and trick blacks and the poor about when and where to vote became common” (emphasis added; Feldman 2015, 303). Equally unsurprisingly, perhaps, the attempts at voter suppression should ring a bell, as these efforts—significantly aided by a 2013 Supreme Court that struck down key provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act—continue to be practiced in the United States.

Together, the first and second Great Meldings created a new and powerful regional identity based on the conflation of economic conservatism, white supremacy/racism, and Christian fundamentalism. (Feldman also points to a Third Great Melding, which involved the fusion of the South’s landed elite and the rising industrial elite.) This amalgamation, put in admittedly overly simple terms, pushed a large segment of the white population in the South (or “plain whites,” in Feldman’s words), regardless of socioeconomic status or class, to be Republicans. Very significantly, while this new identity was originally a mostly, if not entirely, regional one, it eventually transformed into a powerful national one that arguably has a greater impact on American politics today than at any time in the past. To be sure, in the transition from a regional identity to a national one, the overt elements of racism or white supremacy were whitewashed, as it were. That is, the racist elements were hidden from view, disguised, and perhaps even discarded or rendered dormant to some extent, especially in the latter part of the 20th century and the early 21st century. But the first presidency of Donald Trump and its aftermath seemed to make it clear that racism and white supremacy were never completely “unfused.” This appears to be even more the case in Trump’s second presidency, as a major goal of the administration, at least to one critic, “is to reinscribe the hierarchies of race and gender” (Miller 2025).

History Matters … Because it Matters (Today)

I realize that the foregoing discussion may not sit well at all with many, especially conservative, readers; conversely, it may evoke a collective “Tell me something I don’t already know” from others. There is definitely room for debate on the significance of white supremacy, especially as associated with the Republican Party from the 1980s onward. Without a doubt, too, one can be a Republican and resolutely reject “racism” and white supremacy as an individual. However, I need to emphasize, on this point, that racism is not the same as bigotry, the latter of which can be defined as having prejudicial, narrow-minded, and generally unreasonable views about and intolerance of others based on perceived differences, whether racial or something else (such as sexual orientation, gender, religion, region, and so on). While the two terms are often connected, racism, to repeat, is an overarching ideology that is embedded into whole societies to create and sustain a discriminatory, hierarchical, and unjust social system, wherein the more powerful “racial group” dominates or oppresses people who belong to ostensibly different racial or ethnic groups. In this regard, one may “not have are racist bone in their body” (which really means not being a bigot), yet still unconsciously support or at least benefit from a racist system.

Even more, there are plenty of Black Americans (as well as Latinos, Asians, and others) who proudly and strongly identify as Republican. But the thing about “identity,” to keep in mind, is that it is unavoidably subjective and malleable, especially for individual people. Thus, there is no necessary contradiction between individually or personally rejecting racism and white supremacy and/or being Black, while embracing the Republican Party. Still, it is much harder to dismiss the argument that race played a central role in the transformation of the South from a solidly Democratic region (once simply labelled the “Solid South”), to a solidly Republican one (for the most part).

Similarly, it is not difficult to see that the basic principles of “Southern conservatism”—that is, the melding of economic conservatism, white supremacy/racism, and Christian fundamentalism—has expanded across the country. Lastly, it is not easy to dismiss the argument that in the South specifically and in the US generally, the institution of slavery, even long after it was abolished, created a remarkably durable hierarchy of race that have never been completely or even mostly wiped from the consciousness or, importantly, the institutions of American society.

Moreover, the key point in this section and of the chapter thus far is not that the Republican Party is a racist or white supremacist organization per se. It doesn’t have to be for the argument here to hold water. Rather, the key point is that race/racism has shaped the American party system—and, by extension, American politics and democracy—in fundamental ways. In this regard, history matters because, well, it continues to matter today.

There are three basic reasons. First, it matters in that race/racism is not only responsible, to a significant extent, for creating and sustaining the core political division in the United States, but also that it has diminished the significance of class and weakened (but not destroyed, by any means) the capacity of the wage earning class to unify across racial and ethnic lines and across regional lines. Second, it matters in that dynamics of race/racism has meant and continues to mean less collective and organizational power, as well as less discursive power for the wage earning class. Third, it matters in that the wage earning class has less discursive power since it is less able to speak with a coherent (political) voice. The overall diminution of class power among wage earners, in turn, has enhanced the power of the corporate class and its organizational network, the consequences of which are felt as strongly today as ever.

Back to American Exceptionalism

Despite having many shared characteristics, it’s likely that all countries are exceptional in one way or another. One simple reason for this is that all countries have unique historical experiences. While not all unique experiences continue to matter over many decades or even centuries, some certainly do. One would hard put, for instance, to say that the unique combination of words written hundreds of years ago, in 1787, by 55 men and memorialized in something called a constitution, doesn’t have a profound and continuing impact on American politics in 2024 (and beyond). It should not be a stretch, in this view, to assert that America’s unique experiences with race/racism—which are, when one takes the time to look, abundantly evident throughout American history—continue to matter today, too. The question, then, is how we should understand the impact of race, and its intersection with class, in the current period. As I noted earlier in the chapter, the role that race plays and the impact in has on American society and politics, changes over time, both in subtle and obvious ways.

Race and American Politics in the 2000s: More of the Same?

When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, as the first Black president of the United States, many people took that as a sign that racism had finally, at long last, been overcome. In a blog aptly titled, “Racism is over,” one contributor, a police officer, wrote, “It’s been so great to be a police officer since racism has ended. It makes my job so much easier!” Rather than labeling all “brown-skinned people … as inherently more violent and dangerous than everyone else … we [can] now just treat everyone as a citizen who deserves equal respect and investigation if the situation merits it” (Anonymous 2008).

While the comment sounds remarkably naïve in retrospect (and perhaps even when it was written in 2008), it was not necessarily out of step with the general sentiment. One prominent liberal MSNBC news anchor, Chris Matthews, had this to say in referring to Barack Obama: “He is post-racial by all appearances. You know, I forgot he was black tonight for an hour. You know, he’s gone a long way to become a leader of this country and passed so much history in just a year or two” (cited in Real Clear Politics 2010). Another even more prominent conservative political pundit at the time, George Will, simply declared that Obama’s election affirmed that racism is no longer relevant in American politics (although this was something that he believed was true for a long time).[7]

Looking back, it’s obvious that the US did not enter a postracial era; if anything, Obama’s election ignited what a number of scholars and pundits have referred to as the white backlash or “whitelash,”[8] which continued to and through the election of Donald Trump as the 45th (and 47th) president of the United States.

Matthew Hughley (2014) points to the creation of the Tea Party and the Birthers as the key manifestation of the backlash. The Tea Party began as a conservative movement in 2009 and, in principle, was ostensibly only opposed to “big government,” especially government spending (Connolly 2010). While members of the Tea Party vehemently denied accusations that the organization was racist, many members claimed that President Obama was not an American, a claim that, no doubt, was connected to the color of Obama’s skin. Moreover, the Tea Party’s rallying cry of “Take it back, take our country back!” clearly appealed to white supremacist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Minuteman Project, the latter of which was an anti-immigrant and nativist vigilante organization. The Tea Party’s questioning of Obama’s citizenship, as I’ve already suggested, was also clearly tied into the Birther movement, the latter of which, according to Hughley, conflated whiteness with “authentic citizenship.”

In the context of the history of American politics, there was nothing innocent or accidental about this “conflation of whiteness and authentic citizenship.” As Adam Serwer, writing for the Atlantic (2020), put it, “Birtherism was a statement of values, a way to express allegiance to a particular notion of American identity.” That Birtherism, according to Serwer, became a central theme of Donald Trump’s 2015 campaign for the presidency, then, is no accident as his underlying message, while cloaked in “plausible deniability,” was nonetheless clear. “To Make America Great Again,” in Serwer’s words, was “to turn back the clock to an era where white political and cultural hegemony was unthreatened by black people, by immigrants, by people of a different faith.” In this view, there is little doubt that race/racism has continued to play a central role in the core political division in the United States between the Republican and Democratic parties.

There is, it is important to emphasize, strong empirical evidence to support this position. Zoltan Hajnal’s (2020) careful analysis of voting results, not only from the 2016 presidential election but also from elections over a two decade-long period, demonstrate, quite nicely, that “race remains the most powerful force dividing voters.” Moreover, this racialized voting pattern has intensified since the 1960s, when white and Black support for the two parties was about even. By 2008, though, “almost all of the votes that Republican candidates receive come from White voters.” Since 2008, as Hajnal points out, roughly 90% of the vote for the Republican candidates, John McCain (2008), Mitt Romney (2012), and Donald Trump (2016), came from white Americans. (Conversely, Black voters have switched just as strongly to the Democratic Party.) Hajnal’s blunt conclusion? “The Republican Party is for almost all intents and purposes a White party.”

Importantly, too, this division is particularly strong among working class voters. Low income, white working class voters, as Hajnal shows, strongly support the Republican Party while equally low income, Black (and other ethnic minority) voters strongly support the Democratic Party. Hajnal rhetorically asks the same basic question posed previously in this chapter, “Why would working-class Whites who could potentially gain by aligning with racial and ethnic minorities choose to buy into this racial narrative?” And he adds to this by posing another previously asked but important question, “… [W]hy would recent growth in income inequality heighten racial divisions when increased economic inequality could instead create an incentive for all disadvantaged groups to work together to bring about a redistribution of economic resources?”

Hajnal’s answer reflects the earlier discussion on “white identity politics.” Specifically, “For working-class Whites, falling further behind can actually spark more attacks against minorities, and can provide greater motivation to align with other Whites.” His answer also underscores an important implication of the racial division, and one that I have emphasized multiple times. Specifically, the continuing and, even more, strengthening of the racial division along partisan party lines disproportionately benefits the corporate class. This statement, of course, is based on the assumption that the Republican Party is more pro-big business than the Democratic Party. The next section briefly examines this assumption. (An important aside: It’s also important to examine the extent to which the Democratic Party supports corporate class interests over the interests of the general public; if there is no substantive difference, then the partisan division becomes less significant, although not necessarily insignificant.)

The Corporate Class Bias of the Republican Party

Whether the Republican Party is substantively more pro-big business than the Democratic Party is an important question and one that will be addressed in greater depth in Chapter 6. Suffice it to say, for now, that even during the first Trump administration—which was an atypical administration in many significant ways (also a topic for the same chapter)—the corporate class benefited greatly from policies his administration prioritized, especially during the first two years during which the Republicans controlled both the House and Senate. (The second Trump administration, for now, seems to promise more of the same. However, this is not entirely clear as of July 2025).

The most important legislative achievement during Trump’s first term was the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which slashed the nominal corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% (I write “nominal” because many corporations, as noted earlier, do not pay the stated maximum rate—more on this shortly); this worked out to a $233 billion drop in actual taxes paid by corporations over just the first two years of the Act (Hendricks and Hanlon 2019). Not surprisingly, there are dueling interpretations of the overall effects of the Act by liberal think tanks, on one side, and conservative think tanks on the other side. With this in mind, the independent and non-partisan Congressional Research Service (CRS) concluded, as reported by Forbes magazine, “that the 2017 tax cuts for the richest Americans and corporations did not work.” More specifically, the writer for Forbes tells us that the CRS “confirms what anybody who has been looking at the data already knew: Investment did not boom and workers will not see the promised bump in pay. Instead, the federal government incurred massive deficits while wealth inequality increased to its highest level in three decades” (Weller 2019).

A report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) sheds even more light on the benefits that accrued to corporations. The report showed that the share of large and profitable corporations (corporations with at least $10 million in assets) paying nothing in federal taxes rose from 22% in 2014, before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act became law, to 34% in 2018, one year after the law took effect. Overall, the average effective (as opposed to nominal) federal income tax rate paid by these companies fell from 16% in 2014 to only 9% in 2018. Technically, when corporations pay no federal income taxes, it is because they are allowed to carry forward losses from previous years. In other words, if a corporation didn’t earn a profit one year, then there’s no income to tax. However, the GAO report included data showing that even large companies with profits over several consecutive years were able to avoid playing any taxes over multiple years (data from GAO cited in Wamhoff 2023).

There is, in short, no doubt that the Republican-led effort to “reform” the tax system during the Trump Administration was a huge windfall for corporations. Even more, it unlikely that a Democratic congress and presidency would have passed or even contemplated similar legislation. In the vote for the Republican tax bill, not a single Democratic member of the House or a single Democratic senator voted yes.

Beyond Corporate Class Bias

The racially driven party system in the United States does not only mean that tax, fiscal, and regulatory policies are biased toward the interests of the corporate class, which are the type of policies that provide the clearest most direct material benefits to corporations. This bias is definitely important and is theme of this book in general; however, it is important to recognize and acknowledge that the political and social effects of race/racism profoundly impacted the lives of ordinary people, especially Black Americans and other ordinary people of color, in multiple ways that did not directly or necessarily tie into the interests of the corporate class.

Even the New Deal, which benefitted the wage earning class to the detriment of the corporate class, was shaped, to a significant extent, by embedded racism. As Mary-Elizabeth B. Murphy (2020) explains it, Black workers were largely excluded from the major employment-related projects of the New Deal, including the Agricultural Adjustment Act—which created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)—and the National Recovery Administration (NRA) program. The NRA was meant to provide minimum wages for workers in various industries, but it excluded the central positions where black male workers labored. Consider to the Social Security Act. Here is how Murphy summarizes the key point:

The Social Security Act epitomized the New Deal’s negligence toward race and sex. Social Security was a revolutionary piece of legislation that granted unemployment insurance and retirement benefits to workers in the United States. It was designed to mitigate the worst effects of the Great Depression by providing income to unemployed workers and preventing poverty among the elderly. But, southern white men who were determined to preserve the South’s racial order … inserted a provision in the proposed Social Security legislation that excluded farmers and domestic workers.…When FDR signed the Social Security Act into law in 1935, it deemed farmers and domestics ineligible, which meant that 87 percent of all black women and 55 percent of all African American workers were excluded.

While the racism embedded in the New Deal was serious, as I discussed earlier, it is also the case that it sparked the major shift of the Black vote from the Republican Party to FDR and the Democratic Party. In this regard, one might argue that the impact of race, while significant, was transitory, especially since the exclusion of Black workers from programs such as social security was eventually overcome. Yet, while the effects of race/racism may have been mitigated in some areas, that clearly has not been the case in other areas. Consider mass incarceration, which is another example of American exceptionalism or what Katherine Becket and Megan Ming Francis (2020) refer to as “US penal exceptionalism.”

For much of its history, the US was not exceptional with regard to its prison population. As late as 1970, the US imprisonment rate was about 100 per 100,000 people—a rate that had more or less held constant since 1930. Beginning the 1970s, though, the rate shot up, increasing more than seven-fold; in 2008, the incarceration rate was 760 for 100,000 US residents or nearly 1 in 100 adults. That same year, another 5 million others were on probation or parole and nearly one in three people lived with a criminal record (cited in Becket and Francis 2020). In 2023, citing the same statistic used in Chapter 2, the incarceration rate declined to 629, but was still the highest level of incarceration in the world. Among peer democracies, the closest was Taiwan at 219, but some peer democracies had rates of 75 or below, including Ireland (75), Sweden (73) Germany (70) Norway (56), Finland (50), and Japan (37) (World Population Review 2023).

More importantly, in the US, Black Americans make up a disproportionately large part of the prison population—they were imprisoned at roughly six times the rate of white Americans (cited in Muller 2021). There are many explanations both for the high rate of incarceration of Black Americans, including those that parallel the South’s efforts to turn the Republican Party into a “White Party.” In the 1960s, the Republican Party understood that crime and race—using coded racial language—could be combined to attract more white voters by associating civil rights activism with criminality (Beckett 1997). This strategy expanded into the 1970s, as racialized rhetoric and imagery became a central—and effective—part of the Republican Party’s electoral strategy. Importantly, the effectiveness of this strategy motivated the Democratic Party to get in on the action, too, by espousing equally tough “get tough on crime” rhetoric, albeit one that, at least on the surface, was not overtly racialized (Beckett and Francis 2020).

Simply racializing crime doesn’t necessarily lead to higher rates of incarceration, but it provided the rationale and even the imperative for the federal government, regardless of which party was in power, to increase funding for local and state law enforcement and enact laws that would put more people, especially Black people, in prison. New drug laws were of central importance. Surprisingly, perhaps, John Ehrlichman, a former Republican advisor to President Richard Nixon (who was president from 1969 to 1974), was quite forthright on the motivation for what became known as the “War on Drugs” In a 1994 interview, Ehrlichman freely admitted that the War on Drugs started as a racially motivated crusade to criminalize Blacks, as well as the anti-war left. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or blacks”, he stated, “but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin and then criminalizing them both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night in the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did” (cited in Taifa 2021).

Not only did the War on Drugs criminalize Black Americans, but it put literally millions of them behind bars—as late as 2017, more 450,000 people were arrested, but not necessarily imprisoned, for heroin and cocaine offences (cited in National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics 2020)—for long stretches of time with mandatory minimum sentence of 10, 20, 30 years or even life in prison (Taifa 2021).

As I alluded to above, the “tough on crime” approach was not limited to the Republican Party. Perhaps as a testament to how deeply entrenched race/racism is in America, the “most far reaching crime bill Congress ever passed” (Eisen 2019)—the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994—was signed and endorsed by President Bill Clinton (1993-2001) and supported by Joe Biden and even Bernie Sanders,[9] the latter of whom is an unabashed socialist and progressive left politician. Two decades later, in 2015, Bill Clinton apologized for signing the crime bill in speaking to the NAACP. He said, “I signed a bill that made the problem worse. And I want to admit that” (cited in Lind 2015). The crime bill he signed was largely responsible for the imposition of long, mandatory sentences.

There are many other issues that could be discussed here, some of which were mentioned in the opening chapter. These include the racial wealth gap between Black and white Americans,[10] which tripled between 1984 and 2009; unequal access to bankruptcy laws (Loo 2009); higher poverty rates, which reflects higher unemployment rates and discriminatory access to jobs; racial profiling in policing, including sometimes deadly police brutality; redlining in housing (originally a product of New Deal legislation, which provided government-insured mortgages for homeowners, but which also designated most neighborhoods where Black residents lived as not worthy of inclusion in homeownership and lending programs[11]); racial disparities in health coverage, health conditions, and mortality (Carratala and Maxwell 2020); racial bias and limited access to higher quality educational opportunities (Goldhaber, Lavery, and Theobald 2015); and so on. In general, these and other issues overlap and intersect in self-reinforcing ways to make the whole greater than the sum of the parts.

The key point, to repeat, is that race/racism in the United States does not just produce a political system that caters to or prioritizes the interests of the corporate class but also—and more obviously—creates a profoundly unequal and inequitable society that profoundly impacts the lives of ordinary people in ways both great and small.

Conclusion: Fusing Race and Class in the United States

Arguments about the significance of race in American politics are often dismissed because they seem to rely on a grand conspiracy by members of the corporate class getting together to plot how they can use or manipulate racial divisions to their own advantage. In this view, race simply becomes tool—as opposed to an independent and integral aspect of American society—that the corporate class uses to enhance its dominant position. Conversely, but in a similar vein, others see race as a “card” (i.e., the victim card) that can be played at various times to give advantage to certain ethnic or racial minority groups, or for liberals more generally to use to undermine conservative arguments. In either version, race/racism is not considered to be of fundamental or of deep importance. It doesn’t have any explanatory power per se, because if it’s merely a tool, those using it will find a different, essentially interchangeable, tool to serve their purposes if the “racial tool” doesn’t work anymore.

As should be clear from the discussion in this chapter, though, race/racism is not a tool or a playing card. Nor is it ancillary to class in the context of American history and politics. Instead, it has, to borrow from the discussion earlier in the chapter, fused or melded with class to the extent that it has become almost automatic to talk about class with a racialized adjective—e.g., “white working class,” “Black middle class,” and so on. Saying that there is a “white working class,” in other words, presupposes that it is distinct from the “Black working class” and that there is a meaningful difference between the two.

At the same time, as Wood (2002) emphasizes, “Capitalism will always have a working class, and it will always produce underclasses, whatever their extra-economic identity [e.g., slave, “free,” white, Black, Latino, Asian, etc.]. It can adapt to changing conditions by changing the meaning of race and ethnicity, so that one group can displace another at the bottom of the ladder …; or the boundaries of racial categories can, if necessary, be redrawn. It could even survive the eradication of racial … categories altogether” (282).

More simply, Wood is arguing that class comes first; it is primary or foundational. In this sense, Wood is saying that class is more important than race. But Wood is talking about capitalism and class as an abstraction. Capitalism and class in the United States, of course, are not abstractions (nor are they abstractions anywhere else in the world). This is the reason why I italicized “in the context of American history and politics” in the preceding paragraph. That is, in the context of American history and politics, race and class have evolved together in such intimate lockstep that it makes sense to see and analyze them as parts of the same whole.

This also suggests that, in other countries, class and race may not be fused or, even if fused, may create a different class-race dynamic. In many European countries, slavery was a significant institution domestically (Combrink and Rossum 2021), but especially in their overseas colonies. Race/racism was and is embedded in European countries, too. But the historical context and politics of those countries varies considerably; thus, the relationship between class and race is not the same as in the United States. Frankly, I do not have the expertise or knowledge, nor do I have the space in this chapter, to discuss the intersection or fusion of race and class in European or other peer democracies. Suffice it to say, then, the fusing of race and class is the United States is “exceptional” and exceptionally important when thinking about and understanding American politics.

Chapter Notes

[1] The original phrase “the city upon a hill,” used by Winthrop comes from scripture and, thus, his use of the phrase was meant to evoke a religious view that Americans were the Chosen people. Despite being written four centuries ago, moreover, Winthrop’s message basically “never got old.” John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, Barack Obama, and many other contemporary politicians have either expressly or indirectly referred to Winthrop’s original usage.

[2] My reference to Sombart’s book is based on a discussion of his ideas by Harris and Rivera-Bugos (2021) in their article, “The Continuing Dilemma of Race and Class in the Study of American Political Behavior.”

[3] I should note that this didn’t mean a complete lack of electoral support for the Republican Party by white voters in the South. One scholar, for example, estimated that, in the 1880 presidential election, the Republican Party received anywhere from 3.0% to 24.0% of the white vote across 11 southern states, with a large percentage of whites not voting. Conversely, while Black voters generally voted Republican, with between 2% and 37% voted for the Democratic Party in that same election (Kousser 1974).

[4] Adolph Reed, Jr. (2017), who writes extensively on race and class, argues the Du Bois was not making a general argument that was meant to extend beyond the era and place he was focused on, which, to repeat, was the late 19th century South. Reed even argues the Du Bois didn’t consider the term “psychological wage” to be all that important, as it was not listed in the index of his book. For this reason, Reed is skeptical of scholars who continue to use the term in context of 20th and 21st century America.

[5] While most scholars accept the importance of race, one pair of scholars, Byron E. Shafer and Richard Johnston (2006), directly challenged this “studied wisdom about post-World War II partisan change in the South” (Feldman 2007, 747). Shafer and Johnston, instead, argue that economic change was primarily responsible for the partisan shift.

[6] For more discussion of economic or “market fundamentalism, albeit from a critical view, see Block and Somers (2016).

[7] There is no citation; this reference is from personal recollection. At the same time, it is clear that Will, who was once one of the leading conservative voices in the United States, was convinced that race was simply a convenient tool and cynical tactic used by liberals to discredit Republicans. On a Fox News show, for instance, Will had this to say: “Liberalism hasn’t had a new idea since the 1960s except ObamaCare and the country doesn’t like it. Foreign policy is a shambles from Russia to Iran to Syria to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And recovery is unprecedentedly bad. So, what do you do? You say anyone who criticizes us is a racist. It’s become a joke among young people. You go to a campus where this kind of political correctness reins, and some young person will say looks like it’s going to rain. The person listening says, you’re a racist. I mean it’s so inappropriate. The constant implication of this that it is, I think, becoming a national mirth [sic]” (cited in Schwartz 2014)

[8] According to John Blake at CNN, “whitelash” was coined by a regular CNN commentator, Van Jones (Blake 2016).

[9] Sanders voted for the bill in 1994. At the time he emphasized that he had “a number of serious problems with the crime bill,” but he felt other provisions of the bill, especially the Violence Against Women Act, were urgently needed. Thus, he reluctantly voted yes (cited in Lopez 2016). Later, in 2019, he stated half apologized by saying he was “not happy” that he voted for the “terrible” 1994 crime bill (cited in Sullivan 2019).

[10] For a full, albeit somewhat dated discussion of the black-white wealth gap, see Shapiro (2004).

[11] These areas were marked in red in government maps; thus, the term “redlining.” More recently, redlining “has become shorthand for many types of historic race-based exclusionary tactics in real estate — from racial steering by real estate agents (directing Black home buyers and renters to certain neighborhoods or buildings and away from others) to racial covenants in many suburbs and developments (barring Black residents from buying homes). All of which contributed to the racial segregation that shaped the way America looks today” (Jackson 2021).

Chapter References

Anonymous. 2008. “Police.” Racism is Over! http://racismisover.blogspot.com/.

Beckett, Katherine. 1997. Making Crime Pay: Law and Order in Contemporary American Politics New York: Oxford University Press.

Beckett, Katherine, and Megan Ming Francis. 2020. “The Origins of Mass Incarceration: The Racial Politics of Crime and Punishment in the Post-Civil Rights Era.” Annual review of law and social science 16 (1):433-452

Blake, John. 2016. “This Is What ‘Whitelash’ Looks Like ” CNN, November 19. https://www.cnn.com/2016/11/11/us/obama-trump-white-backlash/index.html.

Block, Fred, and Margaret R. Somers. 2016. The Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi’s Critique. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Brooks, Corey M. 2016. “What Can the Collapse of the Whig Party Tell Us About Today’s Politics?” Smithsonian Magazine, April 16. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-can-collapse-whig-party-tell-us-about-todays-politics-180958729/.

Carratala, Sofia, and Conor Maxwell. 2020. “Health Disparities by Race and Ethnicity.” CAP, May 7. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/health-disparities-race-ethnicity/.

Combrink, Tamira, and Matthias van Rossum. 2021. “Introduction: The Impact of Slavery on Europe – Reopening a Debate.” Slavery & Abolition 42 (1):1-14

Connolly, Katie. 2010. “What Exactly Is the Tea Party?” BBC News, September 16. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-11317202.

Eisen, Laurent-Brooke. 2019. “The 1994 Crime Bill and Beyond: How Federal Funding Shapes the Criminal Justice System.” Brennan Center for Justice, September 9. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/1994-crime-bill-and-beyond-how-federal-funding-shapes-criminal-justice.

Eurasia Group Foundation. 2019. “Indispensable No More?” Independent America,, September 13. https://egfound.org/2019/09/indispensable-no-more/#_ga=2.228113236.893079465.1690593984-444135229.1690593983.

Feldman, Glenn. 2007. “Book Review: The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South by Byron E. Shafer and Richard Johnston.” Journal of Southern History 73 (3):746-748

Feldman, Glenn. 2013. The Irony of the Solid South : Democrats, Republicans, and Race, 1865-1944: University of Alabama Press.

Feldman, Glenn. 2015. The Great Melding: War, the Dixiecrat Rebellion, and the Southern Model for America’s New Conservatism. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Goldhaber, Dan, Lesley Lavery, and Roddy Theobald. 2015. “Uneven Playing Field? Assessing the Teacher Quality Gap between Advantaged and Disadvantaged Students.” Educational Researcher 44 (5):293-307. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X15592622

Hajnal, Zohan L. 2020. “What Divides Us? Race, Class, and Political Choice.” In Dangerously Divided: How Race and Class Shape Winning and Losing in American Politics, edited by Zohan L. Hajnal, 39-80. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, Fredrick C., and Viviana Rivera-Burgos. 2021. “The Continuing Dilemma of Race and Class in the Study of American Political Behavior.” Annual Review of Political Science 24:175-91

Hendricks, Galen, and Seth Hanlon. 2019. “The TCJA 2 Years Later: Corporations, Not Workers, Are the Big Winners.” American Progress, December 19. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/tcja-2-years-later-corporations-not-workers-big-winners/.

Hughey, Matthew W. 2014. “White Backlash in the ‘Post-Racial’ United States.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (5):721-730

Jackson, Candace. 2021. “What Is Redlining?” New York Times, August 17. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/17/realestate/what-is-redlining.html.

Johnson, Matthew Frye. 1999. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kousser, J. Morgan. 1974. The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lash, Kurt T. 2018. “Enforcing the Rights of Due Process: The Original Relationship between the Fourteenth Amendment and the 1866 Civil Rights Act.” Georgetown Law Journal 105 (5). https://www.law.georgetown.edu/georgetown-law-journal/in-print/volume-106/volume-106-issue-5-june-2018/enforcing-the-rights-of-due-process-the-original-relationship-between-the-fourteenth-amendment-and-the-1866-civil-rights-act/

Lind, Dara. 2015. “Bill Clinton Apologized for His 1994 Crime Bill, but He Still Doesn’t Get Why It Was Bad.” Vox, July 15. https://www.vox.com/2015/5/7/8565345/1994-crime-bill.

Loo, Rory Van. 2009. “A Tale of Two Debtors: Bankruptcy Disparities by Race.” Albany Law Review 72:231-255. https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/490

Lopez, German. 2016. “Bernie Sanders Voted for the 1994 Tough-on-Crime Law. But It’s Complicated.” Vox, April 8. https://www.vox.com/2016/2/26/11116412/bernie-sanders-mass-incarceration.

Luconi, Stefano. 2001. “Italian-American Voters and the ‘Al Smith Revolution’: A Reassessment.” Italian Americana 19 (1):42-55

Martin, Saleen. 2025. “What Does Juneteenth Celebrate? Meaning and Origins, Explained.” USA Today. June 18. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2025/06/18/what-is-juneteenth-meaning-origins/84169239007/

Miller, Cassie. 2025. “Bigoted Beliefs, Racist Ties Found Among Some of President Trump’s Appointees.” Southern Poverty Law Center. March 6. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/hatewatch/bigoted-beliefs-racist-ties-found-among-president-trumps-appointees/

Muller, Christopher. 2021. “Exclusion and Exploitation: The Incarceration of Black Americans from Slavery to the Present.” Science 374 (6565):282-286. https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.abj7781

Murphy, Mary-Elizabeth B. 2020. “African Americans in the Great Depression and New Deal.” Oxford Research Encyclopedias, November 19. https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-632;jsessionid=8AD48CE1720883A33AE6C1810FD33EB6.

National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics. 2020. “Drug Related Crime Statistics ” National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics. https://drugabusestatistics.org/drug-related-crime-statistics/.

Pease, Donald E. 2018. “American Exceptionalism.” Oxford Bibliographies, June 27. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199827251/obo-9780199827251-0176.xml.

Rank, Mark R. , and Lawrence M. Eppard. 2021. “The ‘American Dream’ of Upward Mobility Is Broken. Look at the Numbers.” Guardian, March 13. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/mar/13/american-dream-broken-upward-mobility-us

Rauchway, Eric. 2010. “When and (to an Extent) Why Did the Parties Switch Places?” The Edge of the American West, May 20. http://chronicle.com/blognetwork/edgeofthewest/2010/05/20/when-and-to-an-extent-why-did-the-parties-switch-places/.

Real Clear Politics. 2010. “MSNBC’s Matthews on Obama: “I Forgot He Was Black Tonight”.” Real Clear Politics Video, January 27. https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2010/01/27/msnbcs_matthews_on_obama_i_forgot_he_was_black_tonight.html.

Reed, Adolph, Jr. 2017. “Du Bois and the “Wages of Whiteness”: What He Meant, What He Didn’t, and, Besides, It Shouldn’t Matter for Our Politics Anyway.” NonSite.org, Jun 29. https://nonsite.org/du-bois-and-the-wages-of-whiteness/.

Reeves, Richard V. 2014. “Classless America, Still?” Brookings, August 27. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/classless-america-still/.

Roediger, David R. 2018. The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class London: Verso.

Schwartz, Ian. 2014. “George Will: Liberals Have ‘Tourette’s Syndrome; When It Comes to Racism.” Real Clear Politics, Aproil 13. https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2014/04/13/george_will_liberals_have_tourettes_syndrome_when_it_comes_to_racism.html.

Serwer, Adam. 2020. “Birtherism of a Nation.” Atlantic, May 20. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/05/birtherism-and-trump/610978/.

Shafer, Bryon E., and Richard Johnson. 2006. The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Shapiro, Thomas M. 2004. The Hidden Cost of Being African American: How Wealth Perpetuates Inequality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sombart, Werner. 1979 [reprint]. Why Is There No Socialism in the United States? Armonk: M. E. Sharp. Original edition, 1906.

Starkey, Brando Simeo. 2017. “White Immigrants Weren’t Always Considered White — and Acceptable.” Andscape, February 10. https://andscape.com/features/white-immigrants-werent-always-considered-white-and-acceptable/.

Sullivan, Kate. 2019. “Bernie Sanders: ‘Not Happy’ I Voted for ‘Terrible’ 1994 Crime Bill ” CNN Politics, July 28. https://www.cnn.com/2019/07/28/politics/bernie-sanders-not-happy-terrible-1994-crime-bill/index.html.

Taifa, Nkechi. 2021. “Race, Mass Incarceration, and the Disastrous War on Drugs.” Brennan Center for Justice, May 10. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/race-mass-incarceration-and-disastrous-war-drugs.

Wamhoff, Steve. 2023. “GAO Report Confirms: Trump Tax Law Cut Corporate Taxes to Rock Bottom.” Institute onf Taxation and Economic Policy, January 13. https://itep.org/government-accountability-office-report-confirms-trump-tax-law-cut-corporate-taxes-increased-corporations-paying-zero-taxes/.

Weller, Christian. 2019. “The 2017 Tax Cuts Didn’t Work, the Data Prove It.” Forbes, May 30. https://www.forbes.com/sites/christianweller/2019/05/30/the-2017-tax-cuts-didnt-work-the-data-prove-it/?sh=90169a958c13.

Wolchover, Natalie. 2022. “When Did Democrats and Republicans Switch Platforms?” Live Science, October 17. https://www.livescience.com/34241-democratic-republican-parties-switch-platforms.html.

Wood, Ellen Meiksins. 2002. “Class, Race, and Capitalism.” Political Power and Social Theory 15:275-284

World Population Review. 2023. “Incarceration Rates by Country 2023.” World Population Review. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/incarceration-rates-by-country.