6 “Democracy of Dollars”? The Power of the Corporate Class

Introduction

In their book, Page and Gilens (2017) suggest that American democracy is no longer defined by the principle “one vote, one person” (if it ever was). Instead, in discussing the shift in how the Supreme Court has generally prevented Congress from regulating political money, the American system has moved closer and closer to the principle of one dollar, one vote (113). Of course, things aren’t quite that simple, as Page and Gilens certainly know. Still, their research unequivocally demonstrates money matters when it comes to what government both does and does not do with respect to public policies—the authors make it clear that wealthy Americans don’t always get what that want but can almost always prevent a policy change from taking place.

The authors also sharply distinguish between what affluent Americans want or don’t want the government to do, and what large corporations want or don’t want. While there is clearly overlap between the two categories, they are not one in the same. This is primarily because large corporations are laser-focused on maximizing profits. Affluent individuals (members of the upper and monied classes), by contrast, “often have broad ideological goals unrelated to—or in conflict with—the narrow material interests of business” (139). While Page and Gilens are very much concerned with the political influence of both the affluent and corporations on American democracy, the main focus for the remainder of this chapter will be on latter. At the same time, there will be a focus on individuals when they clearly represent the interests of the corporate class.

The previous chapters, and especially Chapter 5, have provided a framework and context for explaining the political power of the corporate class. It bears repeating that corporate class dominance is built upon an ostensibly democratic electoral system that has been profoundly and fundamentally distorted by racial/racist relations. Dominance of the electoral system has enabled the corporate class to extend its influence into all corners of the government and into the legal-constitutional system as well. Thus, race and class are utterly entwined in the American political system to the extent that it is simply not possible to adequately explain the dynamics of class relations in the United States—and of American politics more generally—without accounting for the deeply embedded impact of race/racism.

This said, it isn’t necessary to repeatedly make explicit references to race/racism (or to class) when applying the CRP framework. The main point to remember is that race/racism is indelibly etched into the class hierarchy and into the core institutions of American politics and society. This, in turn, is a primary (but not the only) factor that has enabled the corporate class to build a dominant position in those core institutions and thus reshape American democracy to serve its interests, often times at the expense of ordinary Americans.

To understand the power and influence of the corporate class in American politics, this chapter will focus on just a few specific policy areas. The first of these areas is corporate tax policy, arguably one of the most important issue for the corporate class.

Tax Policy for the Corporate Class

Death and taxes. The two things that are supposed to be inevitable and unavoidable in life. Unless, however, you’re a wealthy corporation. In 2021, as previously noted, almost 20% of the Fortune 100 paid nothing or next to nothing in taxes—some even had a negative tax bill—despite earning billions of dollars. AT&T, with pre-tax earnings of $29.6 billion, had an effective tax rate of -4.1%. Ford Motor Co. ($10 billion in earnings) paid $102 million in tax or 1.0%; General Motors did even better as it earned $9.4 billion and paid $20 million for an effective tax rate of 0.2%. Of all the Fortune 100 companies in 2021, Amazon earned the most at $35.1 billion but paid only $2.1 billion in taxes (6.1%) (all figures cited in Koronowski et al. 2022). The previous year, in 2020, 55 of the largest corporations in the country paid no federal taxes or received rebates worth $3.5 billion. This meant that the government collected $12 billion less than it might otherwise have received (Miller 2022). Nor are these no-tax years necessarily one-offs. Over a three-year period between 2018-20, 26 large companies including FedEx, Duke Energy, Nike, Dish Network, and Archer-Daniels-Midland all had negative effective tax rates as much as -22.8% (cited in Cohen 2021).

To be sure, focusing on a few dozen companies can easily present a distorted picture. But the bigger picture is not dramatically different. Between 2014 and 2018, according to US Government Accountability Office (GAO), about half of all large corporations (as opposed to all corporations) and 25% of profitable ones,[1] didn’t owe any federal taxes. The average effective tax rate for these large corporations—i.e., the amount actually paid in taxes as opposed to the statutory tax rate—was 16% in 2014 but only 9% by 2018. This large drop reflected a major decrease in the statutory corporate rate from 35% in 2014, to 21% in 2016 (US Government Accountability Office 2023). Before your eyes glaze over from all these numbers, just keep in mind that large corporations most clearly represent the interests of the corporate class, and a primary interest of the corporate class is to minimize the amount of taxes it has to pay.

Keeping Corporate Tax Low or “No”

So, how do some of the country’s most profitable corporations go year-after-year paying low or no taxes (or receiving a tax rebate)? As President Trump might say, “They’re smart.” That is, corporations are taking advantage of “loopholes”—sometimes supplemented by “creative” accounting practices that straddle the line of legality—in the corporate tax code. One of the more important methods of lowering taxes is shifting profits to overseas tax havens; tax havens are countries that have low taxes combined with low residency requirements for foreign entities and individuals who are willing to deposit money into their financial institutions. A useful example of this is Microsoft, which, according to a report by ProPublica, shifted at least $39 billion in US profits to Puerto Rico, “where the company’s tax consultants, KPMG, had persuaded the territory’s government to give Microsoft a tax rate of nearly 0%. Microsoft had justified this transfer with a ludicrous-sounding deal: It had sold its most valuable possession — its intellectual property — to an 85-person factory it owned in a small Puerto Rican city” (Kiel 2020).

Notably, while Microsoft was taking advantage of a loophole, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) decided the company had crossed the legal line and sued it for back taxes after auditing the company in 2012. Ultimately, the IRS determined that Microsoft owed the government $29 billion.

Predictably, Microsoft challenged the IRS, and the dispute dragged out for more than a decade. Importantly, in the early years of the dispute, Microsoft gained the support of the US Chamber of Commerce and the two created the Coalition for Effective and Efficient Tax Administration, which then lobbied senior government officials and Congress arguing that the tactics used against Microsoft were “destroy[ing] cooperative relationships between taxpayers and the IRS”; while they did not succeed in getting the IRS ruling rescinded, they did succeed in convincing legislators to pass a bill that restricted the IRS’s reach in the future (cited in Rainey 2023).

Most companies that avoid paying taxes, though, are never subjected to the type of legal issues faced by Microsoft. Amazon has done particularly well in this regard. The company has, according to analysts, relied primarily on tax credits and deductions, which meant, as Senator Bernie Sanders tweeted in 2020, that a subscriber to Amazon Prime paid more in one month’s membership fee than Amazon paid in federal taxes for three years combined from 2018-20 (cited in Clarendon 2021).

Unlike Microsoft, Amazon’s tax bill was legally unproblematic. On this point, it is important to note that there are certainly valid reasons for tax credits and deductions for businesses. Investment tax credits, for example, are designed to encourage capital investments; research and development deductions are meant to spur technological and scientific innovation. Companies that lose money in one year can carry those losses forward to offset income and reduce taxes in future year. To encourage renewable energy use, companies can also get tax credits for investing in solar and wind projects. Amazon and many large companies make very good use of these provisions.

The tax credits, deductions, tax havens, etc. that large corporations take advantage of, to underscore a very basic but important point, don’t just magically appear. They often—but not always—reflect the power and influence of corporations to shape the tax code to their benefit. Keep in mind that the tax code is written by Congress, which is given that authority by the Constitution. Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution reads, “The Congress shall have Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.”

While there are members of Congress who would be happy to eliminate corporate taxes altogether—in 2023, a group of Republicans introduced a measure to eliminate all individual and corporate income taxes, capital gains, payroll, and estate taxes, which they dubbed the “Fair Tax” (Ewall-Wice 2023)—most Republicans, at least reluctantly, support the existence of a corporate tax. One likely reason, as we saw in the previous chapter, is clear: The large majority Americans, 79%, support raising taxes on corporations. In a different survey in 2017, 62% of respondents said they are bothered “a lot” by the feeling that some corporations don’t pay their fair share of taxes, while another 18% said they were bothered “some.” Among only Republicans/lean Republicans, 44% indicated they were bothered “a lot” (Pew Research Center 2017).

A Little Background

Significant corporate taxes are primarily a mid-20th century phenomenon. The first corporate tax appeared in 1909 and was a mere 1% on earnings over $5,000. As the federal government expanded, however, the need to raise revenue increased. The first big jumps occurred in the 1930s under Presidents Hoover and Roosevelt. World War II led to another major increase and, over the next few decades, either increased or stayed high. In 1952, the corporate rate was 52% on income over $25,000; there wasn’t much change until 1988, when it was reduced to 34% on income over $335,000 (the corporate tax rate was tiered until 2018, meaning there were different rates depending on the income level).

The reduction in 1988 (part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986) followed on the heels of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA), which was the largest tax cut in US history, although the biggest beneficiaries were the monied class, as the top individual tax rate was cut from 70% to 50% over three years. The Tax Reform Act reduced individual taxes for the monied class even more, from 50% to 28%. (Actually, even 70% is low compared to the individual tax rate in 1944: 94% on taxable income over $200,000.)

Generally speaking, corporate tax cuts are accompanied by cuts to the individual rates; this helps to make the cuts more politically palatable. Cutting taxes, however, can lead to large budget deficits; thus, after a large tax cut, there is often pressure to increase taxes again. This happened in 1993, when taxes were increased, and some corporate loopholes were narrowed. Republican-led administrations have sometimes been forced to raise taxes—in 1988, then-candidate George H.W. Bush famously said, “Read my lips: No new taxes,” but after he was elected, had to go back on his promise—but tax increases typically occur when the Democratic Party is in control of Congress. (During his term, G.H.W. Bush remained personally opposed to a tax hike but was unable to prevent the Democratically-controlled Congress from increasing several existing taxes.)

However, whenever the Republican Party controls both Congress and the White House, the pressure to reduce the corporate tax rate—as well as the individual tax rate for the highest income earners—will almost always rise. The corporate class took advantage of this situation under Ronald Reagan in the 1980s and under George W. Bush in the 2000s; yet, after the large cut in 1986, the top statutory corporate tax rate remained relatively high. It was not until 2017 that there was a major reduction corporate tax rate. This cut was a key feature of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA).[2] A similar situation is unfolding in 2025 with the passage of the so-called “One Big Beautiful Act (OBBBA). The OBBBA, according to critics, is designed to disproportionately benefit the corporate and monied classes, while adding trillions of dollars to national debt. The proposed spending cuts, moreover, could have a devastating impact on the poor, as the main target of cuts are Medicaid (the primary government program providing health insurance for people with limited income and resources.) and “food stamps” (through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP).

NOTE. While an extended discussion of the OBBBA is warranted, the next section will focus on the first Trump era tax cut, the TCJA.

The Corporate Class, Politics, and the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA)

In 2016, Republicans gained control of both houses of Congress and the executive branch. This provided a golden opportunity for the corporate class to flex its muscles, albeit with an extremely willing ally. Actually, the Republican Party didn’t require much, if any, additional cajoling, as corporate tax reform has been on the Republican’s legislative agenda for well over a decade (Wagner, Zeckhauser, and Ziegler 2020), which reflected years of persistent lobbying. In fact, the time between the release of the “Unified framework for comprehensive tax reform” (September 27, 2017) and when the final bill was signed by President Trump (December 22, 2017) was extremely short: Less than three months.

While the time it took to propose and then sign the bill suggests it would have passed no matter what, it was still important for supporters of the TCJA to convince the broader public that the bill was in the interests of the American people as a whole. To this end, a tried-and-true rhetorical strategy was used (remember the importance of discursive power): The American public was told by Republican leaders, conservative think tanks, and the Trump administration that corporate tax cuts would bring substantial gains for US workers (more jobs through greater investment); to American families by boosting household income as much as $9,000 through higher wages (Council of Economic Advisers 2017); and to the economy as a whole—as Trump stated, the tax cuts would be “rocket fuel” for an economic takeoff (Tankersley and Appelbaum 2017).

Moreover, the public was assured that a huge cut in personal and corporate taxes would not result in significantly larger budget deficits and a larger national debt (Tax Foundation Staff 2017). (Note. A budget deficit refers to the amount that government spending exceeds revenues on an annual basis; the national debt represents the sum total of all annual budget deficits or surpluses.) The rhetorical appeal was aimed primarily at skeptical Republican voters, and it worked well. In September 2017, far less than half (41%) of Republicans (and Republican leaners) favored lowering the corporate tax rate (Fingerhut 2017). But by December 2017, Republican approval had shot up to 70% and a short time later, it increased to a high of 82% (Brenan 2019), effectively doubling Republican support in just a few short months.

The short time from proposal to passage left little time for the corporate class to lobby for specific provisions. Thus, almost as soon as the bill was signed by Trump, lobbyists for the corporate class descended on Capitol Hill in order to shape the final version, since before the tax cuts could be implemented, the rules and regulations needed to be formalized. This allowed the corporate class to shave off billions more in tax liabilities than the TCJA originally called for. Here’s how the New York Times described the scene:

Starting in early 2018, senior officials in President Trump’s Treasury Department were swarmed by lobbyists seeking to insulate companies from the few parts of the tax law that would have required them to pay more. The crush of meetings was so intense that some top Treasury officials had little time to do their jobs, according to two people familiar with the process. The lobbyists targeted a pair of major new taxes that were supposed to raise hundreds of billions of dollars from companies that had been avoiding taxes in part by claiming their profits were earned outside the United States. The blitz was led by a cross section of the world’s largest companies, including Anheuser- Busch, Credit Suisse, General Electric, United Technologies, Barclays, Coca-Cola, Bank of America, UBS, IBM, Kraft Heinz, Kimberly-Clark, News Corporation, Chubb, ConocoPhillips, HSBC and the American International Group. Thanks in part to the chaotic manner in which the bill was rushed through Congress — a situation that gave the Treasury Department extra latitude to interpret a law that was, by all accounts, sloppily written — the corporate lobbying campaign was a resounding success (Drucker and Tankersley 2019).

So, did the TCJA fulfill the promises made by Republicans, conservative think tanks, and other supporters? Not surprisingly, there are competing narratives, and the picture is muddled because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which upended economies around the world. Still, there are some relatively clear conclusions that can be drawn from the available evidence. First, it’s clear that households in the top 1% of income earners received the greatest benefit. In 2018, those with incomes of $1 million or more received 216% more refunds than in 2017 and those refunds were 394% higher. Taxpayers with incomes between $50,000 and $100,000, by contrast, received 2.5% more refunds but those refunds were worth 1.8% less than the previous year. Not all taxpayers, though, received even a small benefit, as tax returns showing incomes of just over $100,000 owed more tax, on average (all figures cited in Silva 2008). In addition, advocates of the TCJA argued that ordinary Americans would earn up to $9,000 a year more on average, as the benefits to the monied and corporate classes would “trickle down” to all Americans. However, research by Kennedy and Mortenson (2022), indicates that 90% of workers saw no change in earnings, and that the wage gains that were achieved were concentrated in executive pay and among workers in the top 10% of wage earners.

As for the national debt, during the Trump presidency, it grew by an astounding $8.18 trillion, a 40.43% increase over four years, although a significant portion of that was due to increased spending during the COVID-19 pandemic (Burba 2024). Nor was the TCJA “rocket fuel” for the national economy, as economic growth in 2018 increased by only 0.2% more than anticipated. This was lower than even the most conservative estimates. Importantly, too, corporate profits soared while business investment actually dropped; that is, instead of investing in new factories, technologies, and capital equipment—another big promise made by supporters—the extra tax windfall was largely given to already wealthy shareholders (Hendricks and Hanlon 2019).

The upshot is the TCJA did a lot for the corporate and monied classes, and not very much for the vast majority of American citizens. This is par for the course, but still important to acknowledge. This is because the rhetorical strategies used to justify such policies to the public have proven to be effective, at least from a partisan perspective (e.g., Republicans approval, Democratic disapproval or vice versa). For the TCJA, it is even more important since some provisions were set to expire at the end of 2025. Thus, with the reelection of Trump in 2024 and both houses of Congress controlled by Republicans, there has been another round of intense debate and lobbying over the extension of core provisions in the TCJA. Not surprisingly, the TCJA was both successfully extended and revised in June 2025.

It is worth noting, though, that if the Democratic Party had kept control, things may have played out differently. While still in office, President Biden vowed to let the TCJA expire if reelected. although it’s more likely he would have revised key provisions by cutting or maintaining taxes for some groups, while raising them for others. Biden, for example, stated that he would only raise taxes on those making $400,000 or more (cited in Gleckman 2024). This does not mean that the corporate and monied classes are powerless when the Democratic Party is in charge; that is very far from the case. But the exercise of their power varies, sometimes significantly, depending on which party controls the government.

“Corporate Welfare”: Helping Out the Rich and Powerful

“Corporate welfare” is, admittedly, a loaded and intentionally pejorative term. It’s meant to suggest that corporations receive (undeserved) handouts from the government in the same way that a poor, but healthy adult—one who is capable of working—gets undeserved cash “handouts.” An unfortunate implication of this connection is that corporate welfare, like all forms of welfare, is unjustifiable, which is not necessarily the case (recall the definition of welfare in Box 5.1). Under the right conditions, subsidies may play an essential role in addressing market failures, especially positive and negative externalities. (See Box 6.1 for a simple and brief explanation.) Be that as it may, it’s an equal opportunity pejorative as it is used by both liberal and conservative commentators to criticize government policies that subsidize the corporate sector.

For example, the Hoover Institution, a prominent conservative think tank based at Stanford University, argued that corporate welfare “is the essence of corrupt government” because it puts “Uncle Sam up for sale to the highest bidder …. Corporate welfare … is the antithesis of good government and the antithesis of a free market economic system” (Hoover Institution 1999). Robert Reich, former Secretary of Labor under Bill Clinton and progressive political commentator (and UC Berkeley professor), largely agrees with the Hoover Institution, as he asserts that corporate welfare is an insidious result of lobbying and campaign contributions that essentially takes money away from good schools, roads, Medicare, national defense, and “everything else we need” (Reich 2019). More importantly, the American public is strongly opposed to any form of corporate welfare. In a survey by Rasmussen Reports and the Woodford Foundation, 64% of respondents agreed that corporate welfare should be eliminated, while only 20% disagreed (the rest were not sure). Moreover, there was almost no partisan difference (Rasmussen Reports 2024).

Box 6.1 A Simple Explanation: Market Failure and Positive and Negative Externalities

For economists, “free” markets are wonderful things. Generally speaking, if left alone, markets will produce everything society wants and needs in the right quantities once the forces of supply and demand play out. At the same time, many (but not all) economists agree that there are certain things a free market will under-produce, over-produce, or not produce at all. Economists refer to this condition as a market failure. There are many types of market failures, but the most common are positive and negative externalities. The classic example of a negative externality is pollution. Pollution is a negative externality because it causes harm to other (or for society as a whole). Companies that create toxic by-products, if left alone, would rationally pollute the air and rivers because it’s cheaper to pollute than to pay for properly handling toxic by-products. The only way to get companies to stop polluting the environment is create disincentives, such as a law that imposes huge fines.

A positive externality, by contrast, is something that is good for others or for society. A good example is a cancer drug. The cost of developing an effective cancer drug, however, may be prohibitively high, such that no company would be willing to invest in the research and development on their own. To encourage companies to do this, the government can offer tax credits or other subsidies to reduce the direct cost to the company. In addition, the government can and does provide the company with exclusive rights to produce and sell the drug during which time the drug’s developer is given a government-sanctioned monopoly. This is also a type of subsidy.

While R&D subsidies are generally considered appropriate, given the cost and risk involved, subsidies for other products are more controversial. For example, under the Biden administration, the semiconductor industry was targeted for special treatment through the CHIPS and Science Act. The rationale was that having a strong domestic semiconductor industry is good for the country; the same rationale is or has been used for agricultural goods, fossil fuels and renewable energy, steel, automobiles, among many others.

The seemingly united opposition to corporate welfare—from the right, left, and center—raises the obvious question: “If hardly anyone approves of corporate welfare, except for the corporate class, then why is there so much corporate welfare?” The answer is equally obvious, i.e., money, influence, and lobbying. Nevertheless, it’s still valuable to look at the question and answer in a bit more depth. Before doing so, a quick definition is in order. For the purposes of this chapter, corporate welfare is defined as any type of government-granted privilege that provides financial benefits to firms in the corporate sector. (“Government-granted” includes the federal, state, and local governments.)

Based on the foregoing definition, corporate welfare can come in many forms. One of the most common of these forms is through tax-based policies—e.g., credits, deductions, depreciation allowances, exemptions, deferrals etc. Since the previous section focused on corporate tax policy, tax-related corporate welfare benefits will be generally excluded from the discussion here. Among the other forms of corporate welfare, most fall under the category of (corporate) subsidies, which are taxpayer-funded economic benefits given to an individual firm or whole groups of firms. Subsidies come in different forms, such as cash payments, grants, guaranteed low-interest loans, and guaranteed purchase agreements. Many, if not all, tax-related incentives are also a type of subsidy.

Corporate subsidies, too, have different purposes. In principle, they may be used to incentivize (but usually not require) the production of certain goods or service; to encourage greater employment; to keep companies from relocating their operations outside the United States or to encourage foreign companies to move their facilities to the United States (see Box 6.2); to maintain “stable” agricultural prices, and so on. Trade barriers and tariffs are another type of subsidy. By keeping foreign rivals from freely selling their products in US markets, domestic firms are given a privileged position in those markets; this allows them to sell more products and at higher prices than would otherwise be the case.

Box 6.2 Corporate Subsidies, Not Just for American Corporations

To repeat, subsidies from federal and state governments in the US are not limited to American firms. In April 2024, for example, the Biden administration announced plans to give $6.6 billion, plus an additional $5 billion in government-backed loans, to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) to set up operations in Arizona (Fossum and Cooban 2024). To be sure, from the perspective of the Biden administration, attracting the world’s top semiconductor manufacturing company (responsible for 90% of global production) to set up operations in the United States and create thousands of jobs is good for America. In this regard, the deal is presented as a way of ensuring the US has access to the world’s most advanced semiconductor chips. In addition, TSMC is supposed to invest its own money, more than $65 billion. Still, such deals can and have gone sideways.

Consider that a few years earlier another Taiwan-based company, Foxconn, was offered a $2.85 billion subsidy by the state of Wisconsin on the promise of creating 13,000 high-tech jobs in the state. The jobs never materialized, and the company kept changing plans. It was, as many observers charged, a complete debacle. Fortunately for Wisconsin’s taxpayers, under a new Democratic governor, state officials were able to renegotiate the agreement and brought the subsidy down to just $80 million, albeit with the “promise” of just 1,500 new jobs, which equates $53,333 per job (Cohn 2021).

Whether such subsidies are justifiable or “good for America” is an open question. Whatever the answer, they amount to giving billions of taxpayer dollars to already very wealthy corporations, which could afford to undertake subsidized operations “on their own dime.”

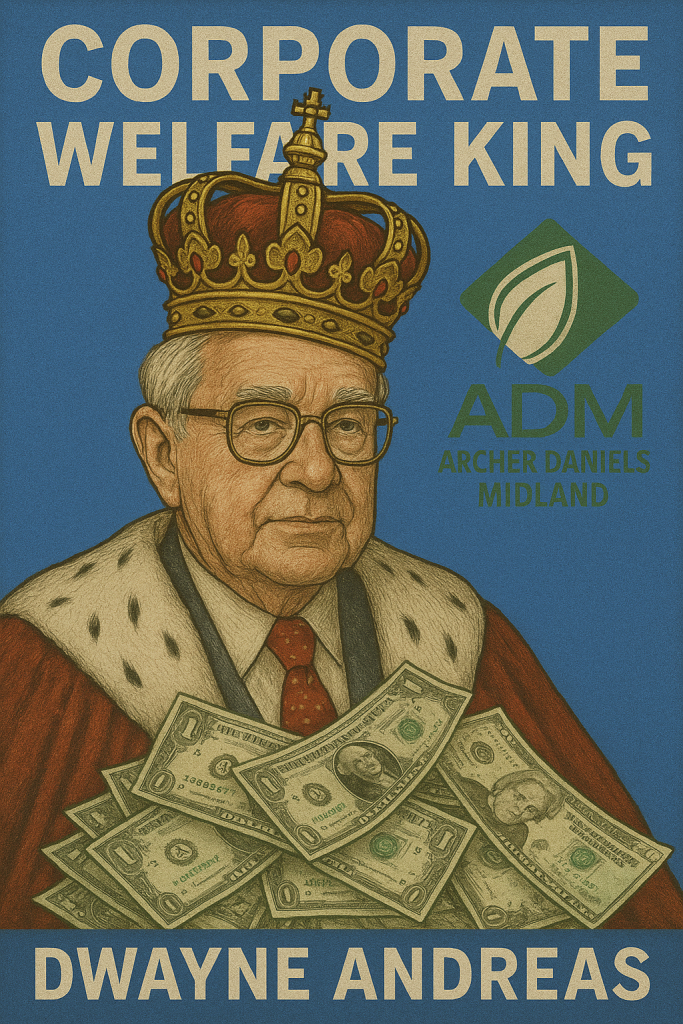

A Closer Look: “Corporate Welfare King,” Dwayne Andreas and Archer Daniels Midland

As I noted above, subsidies draw the ire of both conservatives and liberals alike. In fact, some of the harshest critics are conservatives. I used a quote from a Hoover Institution article at the beginning of this section, but another fierce critic has been the even more conservative Cato Institute (a libertarian think tank). In a dated but still relevant analysis from 1995, James Bovard (1995) of the Cato Institute, examined Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), which was the “most prominent recipient of corporate welfare” at the time. (Note. this section will draw heavily from Bovard’s analysis.)

ADM is no longer the largest recipient of corporate welfare but continues to receive hundreds of millions of dollars from both states and the federal government. It also remains one of the largest companies in the United States, ranking 35th on the Fortune 500 in 2023. A good portion of its wealth is likely owed to the very large of subsidies the company has received over the decades. But the huge subsidies the company has secured had a lot to do with its former CEO, Dwayne Andreas (1918-2016). Fittingly, Andreas’ Wikipedia entry lists his occupation as “American political campaign donor,” while a PBS Frontline article referred to him as “America’s champion all-time campaign contributor” (Frontline 1996). An aside: The reference to the Hoover Institution and the Cato Institute shows that even the most conservative think tanks sometimes put their principles above corporate interests.

Andreas was prolific and shameless in his lobbying and influence-buying; he gave to both Republicans and Democrats, as long as the people who received his money were willing to support his two main business interests, ethanol (made by distilling corn) and sugar. The two parties, of course, knew Andreas was playing both sides and that he had no loyalty to either party; but, again, “as long as he and his cohorts … [were] willing to write checks for millions, members of Congress and presidents … [were] happy to perpetuate billions in handouts for ADM” (Bovard 1995). In the 1992 presidential race, Andreas, his family, and his companies gave a combined total of nearly $1.4 million to the two parties. During that campaign, Andreas ranked first among all donors to the Republican Party and third among Democratic party donors. Even more money flowed to individual candidates; again, he made sure to give a similar amount to both parties. Through one of his foundations, Andreas also “supported” non-profit organizations that were connected to influential politicians. The most egregious case was a $1 million donation to the Red Cross after Elizabeth Dole, wife of then-Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, became its head.

The “billions in handouts” to a rich corporation might have been justifiable if the money ADM received produced an essential product that offered a significant “return on investment” to the American people and the national economy, but that wasn’t the case. As Bovard wrote, “Nothing symbolize[d] ADM’s political exploitation of Americans better than ethanol.” The story here is a bit complicated, as ethanol was, for a time, reasonably portrayed by Andreas and other corn-producers as a viable alternative or supplement gasoline—one use of ethanol was to mix it with gasoline to produce “gasohol.” (Ethanol is still in use, and heavily subsidized, in 2024, a point discussed below.) American political leaders, in turn, were desperate to find an alternative given the then-chokehold that oil-rich Middle Eastern states (and a few others) had on the world’s petroleum supply.

At the same time, it is fair to say that many influential American political leaders were equally desperate for the money that Andreas and the agricultural lobby were willing to provide. For the reason, political leaders are often complicit in “selling a bill of goods” to the American public (“to sell a bill of goods” means to make someone believe a lie). In other words, industry makes a claim, albeit one with some truth, and political leaders repeat it. Over and over again. The media, in turn, plays a role by reporting the claims made by industry and politicians. Even with critical reporting—which there was plenty of in the 1970s and 1980s—just getting the word ethanol into the public sphere was important. In addition, Andreas and others in the industry used PR firms to great advantage. At one point, ADM ran a full-page, full color advertisement in major newspaper showing a corn cob decorated with the American flag with a picture of President John F. Kennedy accompanied by his famous slogan, “Ask not what your country can do for you–ask what you can do for your country.” This advertisement, Bovard wrote, was “the ultimate Orwellian agit- prop exercise, the true message being, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for ADM.’”

Importantly, as the political context changed, so did the rationale for providing ethanol subsidies. In the 1970s, it was energy independence; in the 1980s, it was the need to save “struggling corn farmers”; and into the 1990s, it was portrayed as a greener alternative to oil—a rationale still used today.[3] Whatever the rationale, politicians at the state and federal levels have continued to provide huge subsidies for a product that, as one critic put it, was “not possible to sell for a profit without massive tax subsidies” (cited in Bovard). Between 1975 and 1995, ethanol subsidies amounted to more than $67 billion. But taxpayers were not just paying the direct cost of subsidies, they also paid higher prices for gasohol itself, since other countries, most notably Brazil, were actually underselling US producers. To “rectify” this situation, Andreas and the corn lobby, convinced Congress to slap a prohibitive tariff on ethanol imports. Shortly after the tariff was put in place, Bovard noted, former Democratic National Committee chairman Robert Strauss joined ADM’s board of directors.

This all might be an interesting, but irrelevant, history lesson. But as I noted at the outset, ethanol continued and continues to be heavily subsidized. One key subsidy was a tax incentive called the Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit (VEETC), which was originally signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2004. The subsidy allowed “ethanol blenders” a tax credit of 51 cents for every gallon of ethanol mixed with gasoline (this was later reduced to 45 cents in 2008). In addition to benefitting corn producers, it also gave a tax windfall to major oil companies such as BP, Exxon, and Chevron. Surprisingly, the VEETC was eliminated in 2011 by Congress; not surprisingly, though, ethanol continued to be subsidized through a variety of other programs, one of which has a familiar sounding name, the Volumetric Biodiesel Excise Tax Credit (Taxpayers for Common Sense 2021). The largest current subsidy for corn ethanol, according to a Taxpayers for Common Sense report (2021), is the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) mandate, which is administered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The RFS requires a certain volume of biofuels to be blended with U.S. gasoline and diesel each year.

To underscore the continuing influence of the corn lobby, when Donald Trump first took office in 2017, his EPA appointee, Scott Pruitt, announced that the agency might “slightly lower” subsidy payments for ethanol. This suggestion kicked industry lobbyists into high gear, who put pressure on Republican officials throughout the “Corn Belt” states,[4] especially Iowa. Trump quickly backed down (Murse 2021). Under President Biden, not much has changed. In fact, the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act—arguably Biden’s most significant legislative achievement—included “the biggest federal biofuels spending package in 15 years”; meanwhile, the EPA did the ethanol industry a huge favor by waiving a ban on summertime sales of “E15 gasoline,” i.e., gasoline with up to 15% ethanol content (Graham 2023).

While some readers might reasonably ask why this section has mostly focused on Dwayne Andreas (as well as his company and the corn industry more generally), the reason is simple: It demonstrates how just a single individual can influence public policy and funnel billions of taxpayer dollars into his company and industry. Now, consider this question: “What happens when hundreds of equally well-positioned actors in the corporate class all clamor to do exactly the same thing?” It doesn’t take much imagination to understand how the corporate class as a whole is able to “get what it wants,” even if what it wants is not what the American public wants.

Moreover, what the corporate class wants, it is important to reemphasize, often comes directly out of the pockets of American taxpayers and voters. At the same time, these same Americans continue to vote for the elected officials and political parties who are, figuratively, picking their pockets. To be sure, in almost any democratic system, the corporate class will be able to get a lot of what it wants. But, in a democracy distorted by racialized class hierarchy—as well as a federal system that gives the smallest of individual states outsized power (Wyoming, population of 584,000, has the same number of senators as California, which population of close to 40 million)—the corporate class is able to maximize its political power.

Partisan Politics and Climate Change

Nearly all actively publishing climate scientists (99%)—i.e., the experts on the science of climate change—agree that humans are responsible for global warming and climate change. In other words, there is, for all intents and purposes, no scientific debate among experts about whether or not climate change is human-caused; even more, according to a comprehensive analysis of the peer-reviewed scientific literature by Lynas, Houlton, and Perry (2021), the consensus among climate scientists may be as high as 99.9%. Most ordinary Americans citizens, around 70%, also agree that climate change (or global warming) is happening (Leiserowitz et al. 2024), although a smaller majority (54%-59%) think it is human-caused.[5] When survey results are broken down by partisan affiliation, however, a stark difference appears. According to a survey by the Energy Policy Institute in 2024, only 34% of Republicans believe that climate change is human-caused, while 67% of Democrats do. It is not difficult to see why this is the case. One basic reason is material self-interest: Republican voters, as Egan and Mullin (2023) explain it, tend to be concentrated in those places that are reliant on carbon-intensive industries, such as coal mining and oil and gas extraction and refining[6]; thus, they likely see acceptance of human-caused climate change as a threat to their livelihoods (admittedly, the issue is likely more complicated).

Despite the significance of material self-interest, identifying as a Republican, by itself, is a stronger predictor of (human-caused) climate change denialism or skepticism. For instance, in Shasta county, California, climate change denialism is as high as 52% (Gounaridis and Newell 2024). Yet, Shasta county definitely does not depend on carbon-intensive industries (major jobs are in office and administrative support, management, sales, food preparation, healthcare, and education); it is a “Republican-intensive” community, though, as 65.4% voted for Donald Trump in 2020 (Data USA 2022).

It is important to understand that the polarized character of climate change skepticism didn’t just automatically arise from being a Republican or working in the coal industry. Nor it is merely a result of Republicans and Democrats always wanting to be on opposite sides on an issue. In their views of tobacco, for instance, virtually all Americans agree (96% in an 2018 survey) that cigarette smoking is very or at least somewhat harmful to health (Brenan 2018).[7] Importantly, the near-unanimous and bipartisan agreement is likely due to the scientific consensus on the dangerous health effects of cigarette smoking. Even most smokers apparently agreed with the science, since only around 12% of adults still smoked cigarettes in 2021 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2023).

In other words, scientific knowledge can be effective, even in the face of extraordinarily heavy industry push-back, which was certainly the case with tobacco companies (for an in-depth discussion, see Michaels 2008). Importantly, while the science on tobacco didn’t become a partisan issue, there is a partisan divide regarding what the government should or shouldn’t do in mitigating the harm caused by tobacco products (Shete, Yu, and Shete 2021). Getting into a discussion of this issue would take us too far afield; suffice it to say that the question of government control does speak to the basic “big government, small government” divide between Democrats and Republicans. (The “anti-vax” movement during the COVID 19 pandemic, I should note, suggests that there are other complications to consider, too.)

The “big government, small government” divide, to be clear, doesn’t explain climate change denialism and skepticism on the scientific consensus. After all, one can agree that the science is correct, but still argue, say, that the market can take of the problem, meaning that there doesn’t need to be government involvement. So, clearly, something else is going on. That “something else” is not difficult to identify. Ever since human-caused climate change (or global warming) emerged as significant issue, there has been a purposeful, well-funded, and systematic effort by industry, voraciously abetted by their Republican allies and politically conservative think tanks, to undermine the science and create doubt in the public.

Ironically, some of the earliest scientific findings were made by researchers working for major oil companies. In 1981, an Exxon researcher named Marty Hoffert created a model that showed the fossil fuels were responsible for warming the planet. He shared his findings with the company, but instead of endorsing his research, as Hoffert explained it, Exxon “spread doubt about the dangers of climate change.” Put bluntly, he charged, “What they did was immoral” (cited in Keane 2020). That marked the start of a decades-long campaign by Exxon and others to confuse the public and give their Republican allies a plausible-sounding cover for their opposition to policies designed to mitigate climate change dangers.

Exxon, of course, was not alone. The industry instinctively understood that organized, coherent, and collective action was necessary. Thus, think tanks with compliant scientists (an early but now defunct one was the George C. Marshall Institute), trade groups such as the American Petroleum Institute, newly formed industry-based organizations and advocacy groups (e.g., the “Global Climate Coalition”), advertising campaigns (involving trade groups and PR firms), appearances of “climate skeptics” on conservative news programs, and traditional lobbying—which ensured that Republican politicians would all dutifully repeat industry talking points—were all combined make sure their message was not only heard, but also deeply embedded in the public discourse.

It is fair to say that they were successful, even very successful. Between 1998 and 2014, Exxon alone gave more than $37 million to 69 groups to spread climate misinformation, but that pales in comparison to two “petrochemical magnates,” Charles and David Koch. They gave as much as $145 million to climate-change-denying think tanks and advocacy groups (figures cited in Pierre and Neuman 2021). One of the most important of these is the Heartland Institute, a conservative-libertarian think tank that has played a leading role in challenging climate change science (Heartland also received funding from Exxon). Heartland’s influence could be found in the upper reaches of the Republican orbit—in 2017, the institute’s co-founder, Joseph Bast, was Donald Trump’s guest at the White House when the president announced that the US would be withdrawing from the Paris Climate agreement (a key international agreement addressing global climate change). Afterwards, Bast told his supporters, “We are winning in the global warming war” (cited in Banerjee 2017).

While it definitely helps to have a president on their side, it’s not always necessary. In 2017, 180 members of Congress (142 members of the House and 38 senators) openly denied the science behind climate change; collectively, they also received more than $82 million from fossil fuel companies (Moser and Koronowski 2017). Notably, the number of climate-denying members of Congress has been declining since 2017. In 2019, the number was 150; in 2021, the number dropped to 139, and in 2023 (the 118th Congress), the number decreased to 123 (So 2024).

The decline probably reflects the increasing difficulty of rejecting an unwavering scientific consensus year after year, especially as the destructive real-world effects of climate change become harder to dismiss. In fact, partly as the result of shareholder pressure, even Exxon (now ExxonMobil) publicly acknowledges the reality of human-cause climate change and the need to address the problem (Banerjee 2017) Yet, as long as Republicans hold either the House or the Senate, even a smaller number of climate denying representatives is generally enough to obstruct meaningful climate action, if only because Republicans who accept the science are still inclined to side with the fossil fuel industry

Thus, even if the all the outright climate change deniers disappeared in the next Congress, Republicans would continue to play an obstructionist role. There is already clear evidence of how this will play out. Instead of rejecting the science, former “deniers” have changed their tactics to attacking the solutions, either as unfair, unworkable, or worse than the problem. As writers for the New York Times noted in a 2022 article, “Few Republicans in Congress now outwardly dismiss the scientific evidence that human activities — the burning of oil, gas and coal — have produced gases that are dangerously heating the Earth.” Instead of denial, though, they insist “that the solution—replacing fossil fuels over time with wind, solar and other nonpolluting energy sources — will hurt the economy.” Republicans also argue that, unless every country, but especially China and India, agrees to comparable cuts in carbon emissions, the US would be foolish to cut its own emissions. It just wouldn’t be “fair.” Or, as Lindsay Graham, the long-time senator from South Carolina put it, “The point to me is to get the world to participate, not just us” (Friedman and Weisman 2022).

Keep in mind, the US was one of only eight countries to reject the Paris climate accord—i.e., it was one of the few countries in the world to not participate. This tells us that the talking points are, for the most part, fake. They are mainly meant to distract, obfuscate, and delay the US government having to take decisive action. But they are also meant to provide plausible cover for Republicans who can now claim that they want to solve the problem but aren’t able to so in way that is good or fair for America. Many of these talking points, moreover, come directly from the fossil fuel industry. In 2017, in justifying his decision to withdraw from the Paris Accord, Trump said, “The cost to the economy at this time would be close to $3 trillion in lost GDP and 6.5 million industrial jobs.” Trump got this statement directly from a study paid for by two corporate groups opposed to climate change legislation, the US Chamber of Commerce and the American Council for Capital Formation, the latter of which was funded by the Koch brothers (Watson 2017). The two assertions and other claims made by Trump, however, were seriously misleading, at least according to a factcheck by Scientific American.

To repeat, the Republican position is or reflects the position of the fossil fuel industry, as well as the position of particularly wealthy members of the corporate class (e.g., the Koch brothers), who have a great capacity to turn a science-based issue into a profoundly partisan one. This strategy is extremely effective in an entrenched and increasingly polarized two-party system, where one of the parties has been largely captured by corporate interests, while having the unwavering support of a major part of the white electorate. The unwavering support, to repeat a basic point, is the product of the class-race-power dynamics that have defined the US political, economic, and social systems for centuries. To be sure, the Democratic Party is also deeply influenced by the corporate class and its power. But the Democratic Party has at least demonstrated a willingness, not just to fully accept the science on climate change, but also to enact policies that address it.

Under President Obama, in stark contrast to Trump, the US championed the Paris climate accord; his administration also pressured the fossil fuel industry to invest more heavily in “cleaner,” more efficient production facilities; imposed new regulations on auto emissions and fuel efficiency; and funded a renewable energy “revolution,” according to the Obama White House, by providing loan guarantees to support more than $40 billion of investment in renewable energy generation (Office of the Press Secretary 2019). It is important to recognize, however, that such Democratic programs can be and are a significant source of corporate welfare. According to the Los Angeles Times, to cite one prominent example, Elon Musk’s three major companies—Tesla, SpaceX and Solarcity—received almost $5 billion in government (federal and state) support during the Obama years (Hirsch 2015). The support was instrumental in the development of these companies, despite the fact that Musk now claims to be “anti-subsidy” (Lalljee 2021). At the same time, a good deal of government support for Tesla was in the form of guaranteed loans, which the company did a good job of paying back (Biello 2015).

The Biden administration pursued a similar strategy. Biden himself campaigned on the promise of addressing climate change and, if the first two years of his administration during which Democrats held both chambers of Congress, he made clear progress. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was the centerpiece of his efforts. As the title implies, the IRA had other core purposes as well but, in terms of climate change action, it provided hundreds of billions of dollars for clean energy projects, including expanding the electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure and adoption of EVs, promoting home electrification, encouraging the development of new clean energy projects (wind, solar, geothermal), supporting current nuclear power generation, and so on (for more details, see Biello 2015). According to the World Resources Institute, the administration had, by early 2024, already achieved or made significant progress on a number of major goals. These included cutting total greenhouse gas emissions to 50% of 2005 levels, tackling “super pollutants” such as hydrofluorocarbons and methane, requiring all new passenger vehicles sold after 2035 to produce zero emissions, and scaling up carbon dioxide removal (Lashof 2024).

Not surprisingly, the progress made under Biden are being undone in the second Trump administration. See Box 6.3 for further discussion.

Box 6.3 Climate Change Policy and the Second Trump Administration

On July 4, 2025, Donald Trump signed into law the “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act. While the act is mostly unrelated to climate change policy, it nonetheless has been criticized for seriously undermining prior progress and for setting the US on the wrong path. Among the changes are:

• the elimination or de-funding of clean energy tax credits

• stripping the EPA of its power to regulate greenhouse gases

• increasing support for fossil fuel industries

• blocking state climate policies

• eliminating funding for climate science

Whether you agree with the Republican or Democratic positions on climate change is not the point. The point, instead, is that it makes a policy difference depending on which party is “in charge.” As the previous two paragraphs make clear, though, corporate subsidies do not suddenly disappear when the Democrats are in charge; nonetheless, at least under the IRA, Democrats directed more subsidies at ordinary Americans, although corporations and the corporate class still indirectly benefit. In the IRA, to cite a couple of provisions, $4 billion was provided to states to help individuals make their homes more energy efficient (up to $8,000 in rebates for low- and middle-income families); separate rebates of up to $14,000 were provided for installing heat pumps, electric dyers, and the like. Rebates are direct-to-consumers, but corporations benefit by selling more of their products.

Similarly, the $7,500 tax credit for purchasing EVs went to individuals, but companies such as Tesla benefited significantly from increased sales. (Prior to 2022, most EVs qualified for the tax credit, but in the IRA, the rules were tightened so that only cars with significant American content qualified; in addition, price caps were put in place that encouraged manufacturers to reduce the suggested retail price.) Renewable energy companies were also offered tax credits if they paid wages at the same level that workers in the fossil fuel sector earned, the latter of which tend to be relatively high. The administration also encouraged “companies to adopt project labor agreements, which set wage and employment terms between trade unions and contractors for specific projects, to help them comply with the rules” (Groom 2024).

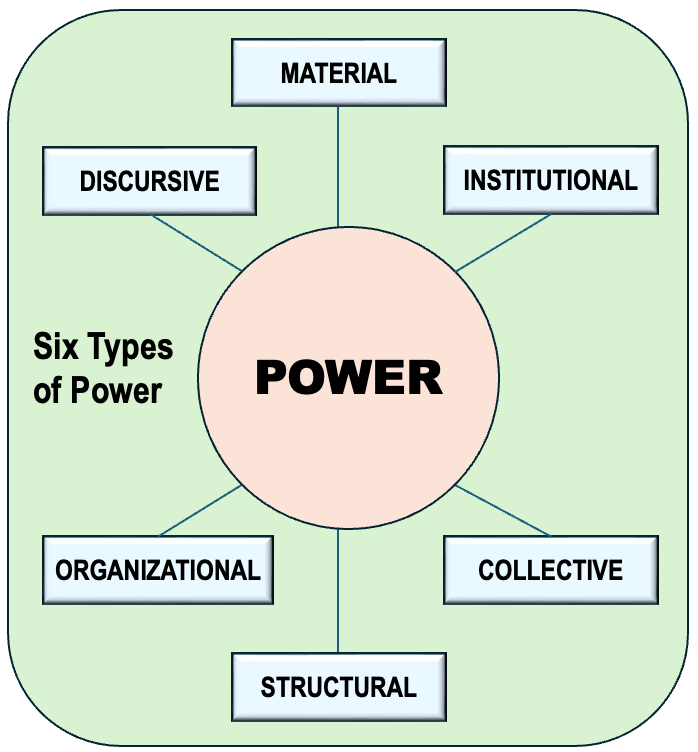

Conclusion: The Corporate Class and the Six Types of Power

The corporate and monied classes have always been wary of democracy. The reason is simple: Since the corporate and monied classes constitute an infinitesimally small portion of the electorate, they worry that American public will elect representatives who, well, represent the interests of ordinary Americans. In principle, then, if ordinary people believe that higher taxes on wealthy corporations is reasonable to pay for better schools, universal healthcare, a cleaner and sustainable environment, and so on, elected representatives will do what they ask. We know, however, that this isn’t always or even mostly the case. The corporate class has learned how to “work the system” to its advantage. The material and structural power of the corporate class is obviously crucial element of this ability to work the system, but those two sources of power can only go so far in the context of a political system where nearly everyone has the right to vote (i.e., a democracy).

To get what it wants, the corporate class has to rely on collective and organizational power by forming trade associations, developing coherent plans of action (as well as coordinating their activities), pooling their money and other resources, etc. But all of this might not be enough if ordinary people fail to elect representatives who systematically favor the interests of the corporate class over voters. To convince voters, reliance on discursive power is essential. The significance of discursive power is easy to overlook or dismiss. But it shouldn’t be. The power of Donald Trump, to repeat a point made earlier, is not because of his material resources per se. Rather, as one pair of scholars argue, his electoral success in 2016 stemmed from the “effective use of an emotionally charged, anti-establishment crisis narrative (Homolar and Scholz 2019). At the policy-level, those who can “control the narrative” can often exercise much stronger and concrete control over the policymaking process (Capano, Galanti, and Barbato 2023).

The significance of discursive power can be surmised through the unremitting efforts to frame or reframe issues in ways that ordinary voters are more likely to support. Mainstream and social media become a primary arena of struggle; of course, for the corporate class, it helps immensely that it owns the most prominent media spaces. While it’s possible to argue that control of media spaces is, therefore, based on solely on material power, that is not generally the case. Sometimes, for example, unquestioned institutional practices play a key role. To see this, consider the “debate” over the science of climate change.

The debate, really a false debate, was aided and abetted by the long-standing belief in mainstream media that “both sides” of an issue had to presented (referred to as “bothsideism”) in order to be “fair and balanced.” Yet, when the scientific consensus is clear, the practice of bothsideism only serves to give undeserved oxygen to a fake narrative; this damages the public’s ability to distinguish fact from fiction (Imundo and Rapp 2022). As I noted above as well, as long as a false narrative survives, it also provides cover for elected representatives to use it to justify their support for policies that the corporate class favors or disfavors. Unfortunately, this often means that the interests of the American public are generally not given much, if any, weight.

Material, structural, collective, organizational, and discursive power all operate within a specific institutional environment. In the United States, as in all democracies, institutional power is found in the three branches of government: Congress, the executive branch, and the courts (the latter of which has started to play an increasingly frequent and significant role). Their institutional power, to be clear, lies in the authority each is granted by the Constitution and the willingness of the people in general to accept their authority and to be bound by the norms, practices, and “rules of the game” that dictate how things are supposed to be done within the country. The three branches, in turn, have the power to create, revise, and enact laws and, to some extent, rewrite the underlying rules of the game.

Obviously, then, this is precisely why the corporate class has targeted all three branches, since institutional power is key to controlling public policy in the United States. In the broader context of American history, the corporate class has found that the most efficacious path to institutional power is through the Republican Party. Again, this is not to say that the corporate class has no power through the Democratic Party. That definitely is not the case. However, the Republican Party has clearly proven to be a more reliable and consistent ally for the corporate class than the Democrats. At the risk of being overly repetitive, it is, finally, important to reiterate that the power of the Republican Party today, is the product of the racialized class hierarchy that has defined the United States since its founding.

Chapter Notes

[1] The GAO defined large corporations as those that filed Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Schedule M-3, which is required for corporations with $10 million or more in assets (US Government Accountability Office 2023).

[2] While the reduction of the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% was the most discussed element of the TCJA, there were other provisions. These included: (1) full expensing of capital expenditures; (2) a limitation on the deductibility of expenses; (3) elimination of corporate alternative minimum tax; (4) switch to territorial taxation of multinational firms; (5) measures targeting income shifting by multinationals; and (6) a one-time “transition tax” on past unrepatriated foreign earnings.

[3] There’s a lot of debate about the environmental benefits or burning corn-based ethanol over gasoline. Suffice it to say that, within the scientific and environmental community, there’s no consensus. One 2022 study, for instance, found that producing and burning corn-based fuel is at least 24% more carbon-intensive than refining and combusting gasoline. The US Department of Energy, however, has criticized those findings (Graham 2023).

[4] This is an unofficial term that, not surprisingly, refers to states that produce a large amount of corn. While there isn’t full agreement on which states compose the Corn Belt, the following can be included: Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Nebraska, Missouri, Ohio, South Dakota, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Kentucky.

[5] As is common with public opinion surveys, different polls using different methodologies and different sample sizes, will not have the exact same results. A “margin of error” is also present in all polls. For the statistics cited, 54% comes from a poll by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (2024), while the figure of 59% comes a poll conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (Leiserowitz et al. 2024).

[6] Other studies have confirmed this relationship. For one study that focused on the specific relationship between fossil fuel dependence and attitudes on climate change, see Knight (2019).

[7] 82% said tobaccos is “very harmful”; 14% said “somewhat harmful”; and 2% “not too harmful.” Only 1% said “not at all.”

Chapter References

Banerjee, Neela. 2017. “How Big Oil Lost Control of Its Climate Misinformation Machine.” Inside Climate News, December 22. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/22122017/big-oil-heartland-climate-science-misinformation-campaign-koch-api-trump-infographic/.

Biello, David. 2015. “Obama Has Done More for Clean Energy Than You Think.” Scientific American, September 8. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/obama-has-done-more-for-clean-energy-than-you-think/.

Bovard, James. 1995. “Archer Daniels Midland: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare.” Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 241, September 26.

Brenan, Megan. 2018. “Americans Say Marijuana, Vaping Less Harmful Than Tobacco.” Gallup, July 25. https://news.gallup.com/poll/237839/americans-say-marijuana-vaping-less-harmful-tobacco.aspx.

Brenan, Megan. 2019. “Tax Day Update: Americans Still Not Seeing Tax Cut Benefit.” Gallup, April 12. https://news.gallup.com/poll/248681/tax-day-update-americans-not-seeing-tax-cut-benefit.aspx.

Burba, Annabel. 2024. “U.S. Debt by President: Dollar and Percentage 2024.” Consumer Affairs: Journal of Consumer Research, May 15. https://www.consumeraffairs.com/finance/us-debt-by-president.html.

Capano, Giliberto, Maria Tullia Galanti, and Giovanni Barbato. 2023. “When the Political Leader Is the Narrator: The Political and Policy Dimensions of Narratives.” Policy Sciences 56:233–265

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. “Current Cigarette Smoking among Adults in the United States.” CDC, accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm#print

Clarendon, Dan. 2021. “Amazon (Finally) Had to Pay Federal Taxes in 2020.” Market Realist, March 11. https://marketrealist.com/p/how-does-amazon-not-pay-taxes/.

Cohen, Patricia. 2021. “No Federal Taxes for Dozens of Big, Profitable Companies.” New York Times, April 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/02/business/economy/zero-corporate-tax.html.

Cohn, Scott. 2021. “After Wisconsin’s Foxconn Debacle, States and Companies Rethink Giant Subsidies.” CNBC, June 29. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/29/after-wisconsins-foxconn-debacle-states-rethink-giant-subsidies.html.

Council of Economic Advisers. 2017. “Corporate Tax Reform and Wages: Theory and Evidence.” October. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/Tax%20Reform%20and%20Wages.pdf.

Data USA. 2022. “Shasta County, Ca.” Deoloitte, accessed July 17. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/shasta-county-ca/#civics

Drucker, Jesse, and Jim Tankersley. 2019. “How Big Companies Won New Tax Breaks from the Trump Administration.” New York Times, December 30. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/30/business/trump-tax-cuts-beat-gilti.html.

Egan, Patrick J., and Megan Mullin. 2023. “US Partisan Polarization on Climate Change: Can Stalemate Give Way to Opportunity?” PS: Political Science & Politics 57 (1):30-35

Energy Policy Institute. 2024. “2024 Poll: Americans’ Views on Climate Change and Policy in 12 Charts.” EPIC. https://epic.uchicago.edu/insights/2024-poll-americans-views-on-climate-change-and-policy-in-12-charts/.

Ewall-Wice, Sarah. 2023. “A Group of Republicans Are Pushing a So-Called Fair Tax Act – Here’s How It Works.” CBS News, January 26. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fair-tax-act-republican-proposal-how-it-works/.

Fingerhut, Hannah. 2017. “More Americans Favor Raising Than Lowering Tax Rates on Corporations, High Household Incomes.” Pew Research Center, September 27. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2017/09/27/more-americans-favor-raising-than-lowering-tax-rates-on-corporations-high-household-incomes/.

Fossum, Sam, and Anna Cooban. 2024. “Biden to Give Taiwan’s Tsmc $6.6 Billion to Ramp up US Chip Production ” CNN Business, April 8. https://www.cnn.com/2024/04/08/tech/tsmc-arizona-chip-factory-investment/index.html.

Friedman, Lisa, and Jonathan Weisman. 2022. “Delay as the New Denial: The Latest Republican Tactic to Block Climate Action.” New York Times, July 25.

Frontline. 1996. “So You Want to Buy a President? The Players: Dwayne Andreas.” PBS Frontline, January. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/president/players/andreas.html.

Gleckman, Howard. 2024. “Would Biden Really Scrap the TCJA? Would That Raise Everyone’s Taxes?” Tax Policy Center: Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, May 1. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/would-biden-really-scrap-tcja-would-raise-everyones-taxes.

Gounaridis, Dimitrios, and Joshua P. Newell. 2024. “The Social Anatomy of Climate Change Denial in the United States.” Scientific Reports 14 (2097)

Graham, Max. 2023. “Despite What You May Think, Ethanol Isn’t Dead Yet ” Grist, May 5. https://grist.org/agriculture/despite-what-you-may-think-ethanol-isnt-dead-yet/.

Groom, Nichola. 2024. “US Unveils Rules for Subsidies to Boost Clean Energy Wages.” Reuters, June 18. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/us-unveils-rules-subsidies-boost-clean-energy-wages-2024-06-18/.

Hendricks, Galen, and Seth Hanlon. 2019. “The TCJA 2 Years Later: Corporations, Not Workers, Are the Big Winners.” American Progress, December 19. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/tcja-2-years-later-corporations-not-workers-big-winners/.

Hirsch, Jerry. 2015. “Elon Musk’s Growing Empire Is Fueled by $4.9 Billion in Government Subsidies.” Los Angeles Tim, May 30. https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-hy-musk-subsidies-20150531-story.html.

Homolar, Alexandra, and Ronny Scholz. 2019. “The Power of Trump-Speak: Populist Crisis Narratives and Ontological Security.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32 (3):344–364

Hoover Institution. 1999. “Welfare for the Well-Off: How Business Subsidies Fleece Taxpayers.” Hoover Institution: Essays, May 1. https://www.hoover.org/research/welfare-well-how-business-subsidies-fleece-taxpayers.

Imundo, Megan N. , and David N. Rapp. 2022. “When Fairness Is Flawed: Effects of False Balance Reporting and Weight-of-Evidence Statements on Beliefs and Perceptions of Climate Change.” Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 11 (2):258–271

Keane, Phoebe. 2020. “How the Oil Industry Made Us Doubt Climate Change.” BBC, September 19. https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-53640382.

Kennedy, Patick J., and Jacob Mortenson. 2022. The Efficiency-Equity Tradeoff of the Corporate Income Tax: Evidence from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Efficiency-Equity-Tradeoff-of-the-Corporate-the-Kennedy-Mortenson/96f6129231b57560890c9cec93d7a6b7d9390d51.

Kiel, Paul. 2020. “The Irs Decided to Get Tough against Microsoft. Microsoft Got Tougher.” ProPublica, January 22. https://www.propublica.org/article/the-irs-decided-to-get-tough-against-microsoft-microsoft-got-tougher.

Knight, Kyle W. 2019. “Does Fossil Fuel Dependence Influence Public Awareness and Perception of Climate Change? A Cross-National Investigation.” International Journal of Sociology 48 (4):295-313

Koronowski, Ryan, Jessica Vela, Zahir Rasheed, and Seth Hanlon. 2022. “These 19 Fortune 100 Companies Paid Next to Nothing—or Nothing at All—in Taxes in 2021.” CAP 20, April 26.

Lalljee, Jason. 2021. “Elon Musk Is Speaking out against Government Subsidies. Here’s a List of the Billions of Dollars His Businesses Have Received.” Business Insider, December 21. https://www.businessinsider.com/elon-musk-list-government-subsidies-tesla-billions-spacex-solarcity-2021-12?op=1.

Lashof, David. 2024. “Tracking Progress: Climate Action under the Biden Administration ” World Resources Institute, January 28. https://www.wri.org/insights/biden-administration-tracking-climate-action-progress.

Leiserowitz, Anthony, Edward Maibach, Seth Rosenthal, John Kotcher, Emily Goddard, Jennifer Carman, Matthew Ballew, Marija Verner, Teresa Myers, Jennifer Marlon, Sanguk Lee, Matthew Goldberg, Nicholas Badullovich, and Kathryn Thier. 2024. “Climate Change in the American Mind: Beliefs & Attitudes, Spring 2024.” Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, July 16. https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/climate-change-in-the-american-mind-beliefs-attitudes-spring-2024/toc/3/.

Lynas, Mark, Benjamin Z Houlton, and Simon Perry. 2021. “Greater Than 99% Consensus on Human Caused Climate Change in the Peer-Reviewed Scientific Literature.” Environmental Research, October 19. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966.

Michaels, David. 2008. Doubt Is Their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health: Oxford University Press.

Miller, Andrea. 2022. “How Companies Like Amazon, Nike and Fedex Avoid Paying Federal Taxes ” CNBC, April 14. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/04/14/how-companies-like-amazon-nike-and-fedex-avoid-paying-federal-taxes-.html.

Moser, Claire, and Ryan Koronowski. 2017. “The Climate Denier Caucus in Trump’s Washington.” Think Progress, April 28. https://thinkprogress.org/115th-congress-climate-denier-caucus-65fb825b3963/.

Murse, Tom. 2021. “Understanding the Ethanol Subsidy.” ThoughtCo, September 4. https://www.thoughtco.com/understanding-the-ethanol-subsidy-3321701.

Office of the Press Secretary. 2019. “The Recovery Act Made the Largest Single Investment in Clean Energy in History, Driving the Deployment of Clean Energy, Promoting Energy Efficiency, and Supporting Manufacturing.” White House Press Releast, February 25. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/25/fact-sheet-recovery-act-made-largest-single-investment-clean-energy.

Pew Research Center. 2017. “Top Frustrations with Tax System: Sense That Corporations, Wealthy Don’t Pay Fair Share.” Pew Research Center: Report, April 14. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/04/14/top-frustrations-with-tax-system-sense-that-corporations-wealthy-dont-pay-fair-share/.

Pierre, Jeffrey, and Scott Neuman. 2021. “How Decades of Disinformation About Fossil Fuels Halted U.S. Climate Policy.” All things considered, October 27. https://www.npr.org/2021/10/27/1047583610/once-again-the-u-s-has-failed-to-take-sweeping-climate-action-heres-why.

Rainey, Clint. 2023. “Why Microsoft’s $29 Billion Tax Bill Could Be the Knockout Punch in a Decade-Long Fight with the Irs.” Fast Company, October 12. https://www.fastcompany.com/90966659/microsoft-irs-billion-tax-bill-explained.

Rasmussen Reports. 2024. “Nearly Two-Thirds Favor Ending ‘Corporate Welfare’.” Rasmussen Reports, January 26. https://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/partner_surveys/nearly_two_thirds_favor_ending_corporate_welfare.

Reich, Robert. 2019. “How Corporate Welfare Hurts You.” The American Prospect, July 23. https://prospect.org/economy/corporate-welfare-hurts/.

Shete, Sahil S., Robert Yu, and Sanjay Shete. 2021. “Political Ideology and the Support or Opposition to United States Tobacco Control Policies.” JAMA Network Open 4 (9):e2125385-e2125385. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25385

Silva, Fred. 2008. “California’s Two-Thirds Legislative Vote Requirement and Its Role in the State Budget Process.” Western City, November 1. https://www.westerncity.com/article/californias-two-thirds-legislative-vote-requirement-and-its-role-state-budget-process.

So, Kat. 2024. “Climate Deniers of the 118th Congress.” American Progress, July 18. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/climate-deniers-of-the-118th-congress/.

Tankersley, Jim, and Binyamin Appelbaum. 2017. “Trump Sells ‘Rocket Fuel’ Tax Plan as Economy Strengthens.” New York Times, November 29. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/29/us/politics/trump-tax-plan-economy-growth.html.

Tax Foundation Staff. 2017. “Updated Details and Analysis of the 2017 House Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Tax Foundation: Special Report (239). https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/2017-tax-cuts-jobs-act-analysis/

Taxpayers for Common Sense. 2021. “Understanding U.S. Corn Ethanol and Other Corn-Based Biofuels Subsidies.” Biofuel Report, May. https://www.taxpayer.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/TCS-Biofuels-Subsidies-Report.pdf.

US Government Accountability Office. 2023. Corporate Income Tax: Effective Rates before and after 2017 Law Change. edited by GAO. Washington, D.C.: GAO.https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105384.

Wagner, Alexander F., Richard J. Zeckhauser, and Alexandre Ziegler. 2020. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: Which Firms Won? Which Lost?

Watson, Kathlyn. 2017. “How Accurate Was Trump’s Paris Climate Agreement Speech?” CBS News, August 11. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-paris-climate-agreement-speech-fact-check/.