2 American Politics in Comparative Perspective

Introduction

In 2015, the controversial and unabashedly progressive filmmaker, Michael Moore, released a provocatively titled documentary, Where to Invade Next. In the film, Moore travels to various, mainly European countries: Italy, France, Finland, Tunisia (located in North Africa), Slovenia, Germany, Iceland, and Portugal. His intent, not surprisingly, isn’t to invade the countries but instead to highlight stark differences with the United States in a number of important areas. For example, in Italy, he focuses on the seemingly privileged lives of ordinary workers, who enjoy (by law) 20 days of state-mandated paid holidays, paid honeymoons, “thirteenth salary” (a year-end bonus typically equivalent to an employee’s monthly salary), paid parental leave, and 90-minute lunch breaks. In Slovenia and Germany, higher education is free to every student, including international students; Germany, too, has generous labor policies, such as 40 hours of pay for 36 hours of work, which has helped to build and maintain a “thriving middle class” where workers can even a get a prescription (from a universal health care system) for a “free three-week stay at a spa.” In Portugal, after years of assiduously prosecuting a “war on drugs,” the country’s government decided to decriminalize all drugs, including so-called hard drugs, while also providing free medical treatment to drug users. Iceland is a country where gender equality is prioritized, where it’s illegal for companies to declare their products as the “best,” and where white collar criminals (in the case of Iceland, the heads of large banks) are subject to serious prosecution and punishment.

Moore paints a very rosy picture, but as one reviewer of Moore’s film wrote, “His examples of progressive European social institutions are cherry-picked to make American audiences feel envious and guilty” (Holden 2015). Certainly, Moore’s view is heavily tinted by rose-colored glasses. European countries are not, by any means, utopias for workers and ordinary citizens; in fact, many countries in Europe have serious economic, societal, and political problems, much of which is reflected in a rise of populism throughout the region. Notably, in its present-day form and despite its name, populism is closely associated with less democratic and more authoritarian forms of politics and is usually characterized by extreme nationalism and intolerance of already marginalized groups, especially immigrants from Africa and the Middle East (in Europe).

Tellingly, too, while there may be many factors behind the rise of populism, an important one, based on research done by a set of scholars in Spain, is simply anger (Rico, Guinjoan, and Adnuiza 2017).[1] Anger, of course, suggests that people are intensely displeased with things that are happening in their societies and/or are dissatisfied with the state of their lives. Moore’s film, by contrast, makes it seems as if everyone or at least the large majority of the people in the countries he “invaded” are happy; but this clearly is not the case. While the most serious populist movements—that is, those that have led to significant weakening of democracy, which is referred to as democratic backsliding—have been in Eastern and Central Europe (e.g., Hungary and Poland), Western Europe has also seen a rise of right wing populist parties, too, including in France, Italy, Greece, Spain, and Germany.

The Importance of Comparing

In examining politics in the United States in relation to other countries, then, the point is not to make glib comparisons or try to “score (comparative) points” for one side or another—although, I should emphasize that some of the comparative points Moore makes are valid and will be explored further. Instead, the main point is to make comparisons that allow us to learn something that might not otherwise be apparent. As I’ve previously noted, comparisons can also help explain how and why things work the way they do in American politics. On this last point, it is important to understand that comparing is a method of analysis. Methods, which are integrally tied to evidence (or facts), are used by social scientists as a way to support (or challenge) an argument. Without using a method of analysis, along with appropriate (i.e., relevant, reliable, and sufficient) evidence, there is no way to test or properly evaluate an argument to know whether it is right, wrong, or something else.

Put another way, an argument without method and evidence is nothing more than unsupported opinion. Indeed, one of the biggest problems in everyday political discourse—especially the type you see on TV—is that ostensibly serious arguments are broadcast without ever being tested or evaluated in a reliable and intellectually honest way. Just the opposite happens; that is, either arguments are made without any effort to support or test them, or they are “supported” or “tested” in a completely biased or dishonest manner. Even worse, many people readily accept such arguments (viz., unsupported opinions), usually because it confirms a view or position they already hold. At the same time, there are many other people who don’t know what method is or don’t understand the importance of method; obviously, in those cases they will also not have learned how to properly evaluate the methodological merits of an argument.

While it’s well beyond the scope of this book to provide an in-depth discussion, much less application, of method or methodological principles, as I proceed—not just through this chapter but also throughout the book—I will at least provide a few very simple but useful pointers to help identify sketchy arguments using very basic, but useful methodological and, more specifically, comparative tools.

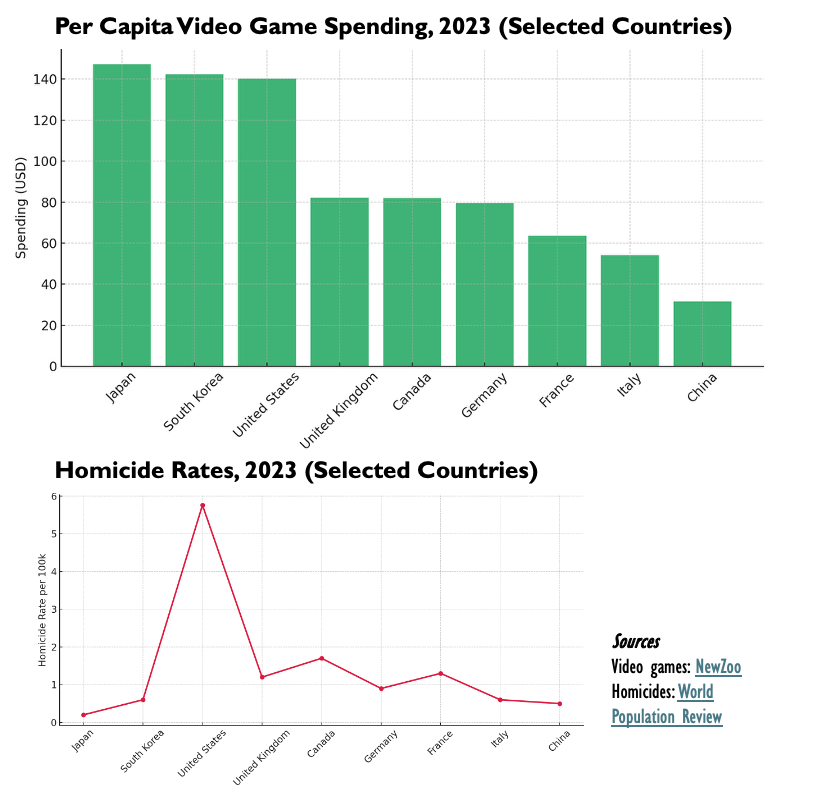

A concrete example might help to clarify the key issue. One particularly sketchy argument is put forward almost every time a mass shooting takes place in the United States, particularly when the assailant is young. After the murderous and tragic rampages at Columbine High School in 1999, at Sandy Hook elementary school in 2012, at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018, and at a Nashville Christian school in 2023 (to name just a few of the many and continually increasing number of mass shooting), one commonly heard argument was that the root cause of these shooting was exposure to violent video games. To be sure, the people who made and continue to make these arguments—including the CEO of the NRA, President Donald Trump (in his first term), and many TV pundits—were likely being disingenuous or cynical at best. Be that as it may, their arguments about the causal importance of violent video games have been generally accepted: According to a 2017 Pew Research poll, a strong majority of adults (60%), especially senior citizens (82%), believed video games contributed either a “great deal” or a “fair amount” to gun violence (Parker et al. 2017). A basic bit of comparative analysis, though, immediately and definitively tells us that exposure to violent video games cannot be a main cause of violent gun deaths.

Consider this very simple comparison: The country with the highest per capita video game revenue is Japan (Newzoo 2022), with violent first-person shooter games, such as Call of Duty, typically among the strongest sellers. If those who argue that violent videos are partly or even mostly responsible for gun and other homicides are right, Japan should, even must, have the highest or one of the highest homicides rates in the world. It does not. Instead, it has one of the lowest: The gun homicide rate in 2017 was exceptionally low at 0.4 per 100,000 people; even more, in 2021, there was, quite remarkably, only a single gun homicide in all of Japan, a country with a population of 125 million people (Maruyama 2022). Japan’s total homicide rate is also very low, as the graph below helps to illustrate. In the US, by contrast, the gun homicide rate was 4.43 (equal to 10,982 homicides by firearms) or over 110 times higher than the rate Japan in 2017 (statistics for US from Federal Bureau of Investigation 2017). A wider comparison using more countries would demonstrate very little correlation, if any, between exposure to violent video games and homicidal gun violence.

Thus, through some simple and easy-to-do comparisons, it is reasonable to conclude that, by itself, exposure to violent video games is not a major, much less sole, cause of gun violence. In other words, we know, with a near-certainty, that there are other factors or possible causes, although our basic comparison doesn’t tell what these other causes are (nor does the comparison allow us to conclude that exposure to violent video games is completely irrelevant; it may be relevant, but only in conjunction with other factors—e.g., easy access to firearms, societal norms that promote violence, etc.).

Thus, through some simple and easy-to-do comparisons, it is reasonable to conclude that, by itself, exposure to violent video games is not a major, much less sole, cause of gun violence. In other words, we know, with a near-certainty, that there are other factors or possible causes, although our basic comparison doesn’t tell what these other causes are (nor does the comparison allow us to conclude that exposure to violent video games is completely irrelevant; it may be relevant, but only in conjunction with other factors—e.g., easy access to firearms, societal norms that promote violence, etc.).

American Politics in Comparative Perspective

As I emphasized in Chapter 1, the United States differs and even stands out from other democracies in numerous ways. But the US isn’t completely different. After all, by definition all democracies are, well, democracies in that they have universal and equal suffrage, regular and fair elections, an effective legal framework of civil liberties and rights, and a competitive multiparty system (recall Box 1.2 in Chapter 1). As with all other democracies, too, the US has a market-based or capitalist economy, which has the same functions and organizational elements around the world. Thus, while it’s seemingly trivially obvious to say that the US is both similar and dissimilar to other capitalist democracies, it’s still a useful point to make for a couple of reasons.

First, the similarities suggest that democracy and capitalism are powerful homogenizing forces; that is, they create a significant degree of economic and political uniformity around the world regardless of the specific circumstances of individual societies. Second, the fact, as I have already noted and as the subsequent discussion in this book will show, that there are significant differences among capitalist democracies tells us that, while capitalism and democracy may be powerful forces, they are not all powerful. More to the point, the differences suggest that country-specific factors, such as race/racism, religion and other cultural factors, and specific historical and institutional dynamics (the latter of which may involve cross-border or international issues) can all play a role in determining what happens inside a country in general and in in their political dynamics more specifically.

Basic Similarities Between US and Its Peer Democracies

A slight majority of countries in the world are democratic. In 2022, according to research done under the Regimes of the World (RoW) project, out of a total of 178 countries, 90 were democracies (cited in Herre 2022).[2] Typically, though, when political processes and outcomes in US are compared to other democracies, a much smaller set of peer democracies—i.e., those with relatively high per capita GDP and stable political systems—is used. This is partly because it’s more manageable, but it is also because economic wealth and political stability are themselves (potentially) important factors. The logic is as follows: A poor and politically unstable democracy is unable to do many of the things a far more prosperous and politically stable democracy can. Jamaica is a good example, as its per capita GDP of around $6,300 in 2023 (that same year, per capita income in the US was just over $80,000[3]) makes it one of the poorest countries in the world, and the existence of powerful criminal gangs and widespread corruption creates a great deal of political instability. Under such conditions, many of the policies that richer democracies are able to effectively pursue are essentially out of reach for Jamaica.[4]

For the purposes of this book, then, the peer democracies include most Western European countries (e.g., UK, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Belgium, Denmark, Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, France, etc.), the Nordic countries (Norway, Finland, and Sweden), Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan (see Box 2.1 for a full list of peer democracies). A couple of notes: First, I will not be engaging in a systematic or in-depth comparison of these countries and the United States.[5] Far from it. Instead, I am listing them just to give a more specific sense of the term, “peer democracy.”

Most of the comparisons, in this chapter especially, will be based on comparative (descriptive) statistics done by other researchers; that is, I’ll be relying on secondary sources. Second, the US is often compared to members countries of the OECD (the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), which is an international organization that was originally composed of 20 wealthy, almost entirely western democracies (plus Türkiye or Turkey). Over the years, membership has increased to 38 to include countries in Asia, other parts of Europe, and Central and South America (e.g., Mexico, Costa Rica, and Brazil). Since the OECD regularly produces comparative statistics, some comparisons will be of the US and other OECD countries in general, rather than being limited to a smaller set of “peer democracies.

| Box 2.1 Peer Democracies | |||

| Australia | Austria | Belgium | Canada |

| Czech Republic | Denmark | Finland | France |

| Germany | Greece | Ireland | Italy |

| Japan | Korea (South) | Netherlands | New Zealand |

| Spain | Sweden | Switzerland | Taiwan |

| United Kingdom | United States | — | — |

| *This is a somewhat arbitrary list. However, the basic criteria for inclusion are: (1) a stable democratic political system, (2) high-income as defined by the World Bank, and (3) a population of at least 10 million people. The countries on this list also possess the five attributes discussed in this section. All are members of the OECD except for Taiwan, which is generally excluded from international organizations, such as the OECD and United Nations, as result of China’s claim that Taiwan is a province of China—a claim that is officially recognized by most other countries and international organizations. One omitted country is Israel, which is a high-income democracy and member of the OECD. However, according to Freedom House, the rule of law in Israel has serious deficiencies (Freedom House 2023); Israel also has an especially complicated international situation, which sets the country apart from other peer democracies. |

|||

With the foregoing in mind, what are some of the most basic similarities between the United States and its democratic peers? In Chapter 1, you may recall, two key similarities were mentioned. The first was that the US and its peers all have the same class divisions. Specifically, they all have a main division between those who work for living—which is divided into the lower income, the upper income, and monied classes—and a corporate class. Second, the corporate class is a major political actor in all peer democracies, although, importantly, it is not necessarily the most powerful political actor. Institutionally, there are also readily apparent similarities. One of the most significant is the protection of an individual’s right to private property, which includes owning a private business or enterprise.

Closely connected to respect for private property is the protection of private contracts, which is a necessary element of a smoothly functioning capitalist market system. While these protections are typically taken for granted, there are capitalist economies—especially non-democratic ones such as China, Russia, and Venezuela (and, yes, “Communist China” has a capitalist economy)—where respect for private property is far from sacrosanct.[6] Even in democratic countries, there is variation in the degree to which property rights are protected, although most peer democracies are closely bunched (for ranking of property rights, see Heritage Foundation 2022).

The issue of protecting property and contract rights raises the question, “Who provides the protection?” The simple answer is the state,[7] which is another core similarity. States, to be sure, are a ubiquitous feature of the modern world. However, the US and its peer democracies are characterized by having states with the following combination of attributes, two of which were already mentioned: a good degree of political stability[8] and strong protection of civil rights and liberties. The two other attributes are a relatively low level of corruption and adherence to the rule of law. There is one additional attribute that needs to be mentioned, namely, state capacity. State capacity refers to “the state’s ability to attain its intended policy goals, whether they be economic, fiscal, or otherwise” (Dincecco and Wang 2022). The US and its democratic peers all have strong state capacity.

While these five, partly interrelated, attributes may constitute another set of taken-for-granted similarities, they are important to highlight since, to repeat, not all democratic states are alike. To use the example of Jamaica, once again, it is not only a politically unstable and relatively poor democracy, but it’s also one in which state capacity is weak (by the way, I’m mindful of the fact the problems in Jamaica reflect a complicated history—it was occupied by Spain in 1509 and then colonized and ruled by Britain from 1670 until 1962—and unequal power relations after its independence). As one scholar at the University of West Indies in Jamaica wrote, while Jamaica is not technically a failed state (that is, a state with little to no capacity), “There seems to be a general feeling among many average Jamaicans that the country has slumped into a desolate place full of ‘sufferation’ and hopelessness” (Gordon 2018). Thus, when comparing the US to other democracies, it’s important to establish a baseline for valid comparisons, which is the basic reason for comparing the US to peer democracies.

How the US Differs from Its Peer Democracies

Inequality and Living Standards: The US and Its Peers

Any close look at even just a pair of democratic peers will reveal a lot of differences, so the focus on this section will be on the strongest policy-based differences between the United States, on the one hand, and its democratic peers on the other hand. (By “policy based,” I am referring to differences that arise from a political process and from public policy decisions made by state or governmental actors.) One of the most salient policy-based differences is income inequality, which is generally the product of a range of intentional policy decisions.

A report by the Economic Policy Institute lists a number of policy decisions that lead to greater inequality, including “withering labor standards,” lack of enforcement against wage theft, policies that reduce worker bargaining power, and “loose governance oversight” (Gould and Kandra 2022). In measuring income inequality, one of the most used tools is the Gini (Coefficient) Index, which measures the extent to which the distribution of income among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. Based on this index, the US ranks dead last among its peer democracies, with Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, Denmark, and Sweden among the least unequal in terms of income distribution. The Gini Index is a useful statistic, but it doesn’t tell us much about conditions on the ground. For example, in wealthy democracies, even with a relatively high degree of income inequality, the standard of living for the lower income class and others may still be adequate and even comfortable.

In many respects, the US does quite well with regard to the standard of living for the bulk of the country’s people. In the OECD “Better Life Index,” for instance, the US was ranked first in household income and third highest in household net wealth (out of 41 countries, including all peer democracies plus additional non-peer countries), despite the comparatively high degree of income inequality. Housing expenditures compared to other OECD countries was also fairly low in the United States. The US also ranked better than the OECD average in overall “life satisfaction” (14th highest), which is basically a measure of general “happiness,” or as the Index describes it, “Life satisfaction measures how people evaluate their life as a whole rather than their current feelings.”[9] Somewhat contradictorily, though, the US has the third highest suicide rate among OECD countries, behind only Japan and South Korea (Gunja, Gumas, and Williams II 2023).

Differences in the Healthcare System

The foregoing differences, as apparent as they may be, end up painting a fuzzy picture. There are, however, some policy-based differences that are much sharper. One of these relates to health policy. As I’ve already noted, the United States is the only peer democracy without some form of universal healthcare. Why this is the case is complicated, as is the question of whether it is good, bad or something else. In fact, there is no shortage of people who argue that the mostly privatized healthcare system in the US is superior to any government-funded healthcare systems in the world (for one example, see Chen 2018).

While there is certainly room for legitimate debate, suffice it to say, for now, that healthcare outcomes in the US reflect significant shortcomings in overall quality. The data on this point are clear-cut. The US, for example, has the highest rate of infant and maternal deaths among OECD countries (which includes a few countries that are much poorer than the US); it also has the highest obesity rate, the highest rate of multiple chronic conditions, the lowest life expectancy at birth, and the highest death rate for avoidable or treatable conditions (Gunja, Gumas, and Williams II 2023). Moreover, in a study expressly comparing the US to ten other high-income democracies (all peer democracies), the US ranked last in access to care, administrative efficiency, equity, health care outcomes, and in the overall score (Schneider et al. 2021).

At the same time, the wait times for seeing specialists or getting elective surgery is shorter in the US than in most peer democracies; and the US has the highest (combined) survival rate for three types of cancer, which is a good measure of the quality of medical care (Rice et al. 2020). The ready existence of high quality medical care in the US suggests that, for those with means, healthcare in the United States can be top notch. However, there are millions of people without means, which often results in sub-standard care. One article in the Harvard Gazette summed up the issue bluntly in its title: “Money = quality health care = longer life” (Powell 2016).

This said, I cannot nor do I even what to try to resolve the debate here; moreover, while the question about the relative merits of a government-run, universal system versus a privatized one is certainly relevant, the more important question for this book is why, among all peer democracies and most of the rest of the world, the US has resisted the virtually universal demand for universal healthcare. I will address this and other why-questions in subsequent chapters, but as a preview, it’s not difficult to discern a major factor: the outsized influence of the corporate class that directly profits from a privatized healthcare system.

The US, Its Peers, and “Peacefulness”

Another “less gray” difference between the US and its peer democracies revolves around what one organization refers to as “peacefulness.” As with many issues of general concern, researchers have created an index that endeavors to measure how “peaceful,” both in terms of domestic and international policy, a country is. Peacefulness is not only reflected in non-participation in wars or international conflicts, although this is an important part of the index, but is also designed to measure the absence or presence of violence and fear more generally. For example, a country with few domestic homicides and few incarcerated persons will be more peaceful than countries with a high homicide rate and a large prison population.

To cut to the chase, according to the Global Peace Index (GPI) (Institute for Economics & Peace 2023), the United States is, by an extremely wide margin, the least peaceful among all peer democracies. Indeed, according to the GPI, the US is, overall, among the least peaceful countries in the world, ranking 131 out of 168 countries. The US rank puts it in close proximity to countries (or territories) with profound economic and political problems, such as Haiti, South Africa, Eritrea, Palestine, Lebanon, Libya, and Venezuela. Interestingly, in the GPI, the US is much closer to North Korea—a repressive totalitarian state—than it is to its closest democratic peer, France.

The GPI, it is important to note, measures peacefulness in three areas or domains: “Ongoing Domestic and International Conflict,” “Societal Safety and Security,” and “Militarization.” The first domain is primarily based on counting incidents and deaths from internal conflicts and organized external conflicts (e.g., war). The second domain (Societal Safety and Security) considers a range of factors, including domestic homicides, level of violent crime, violent demonstrations, jailed population, and ease of access to small arms. And the third domain, Militarization, focuses on military expenditures, number of armed services personnel, the transfer of weapons, and nuclear and heavy weapons capabilities.

All three domains reflect, for the most part and most of the time, intentional policy-based choices. This is especially easy to see in the domain of militarization—where the US ranks as the third least peaceful country in the entire world, behind only Israel and Russia—since military spending is clearly a choice that state actors make and debate, typically on an annual basis. At the same time, it could be argued that, in a dangerous and uncertain world, states and especially large states such as the US have little to no choice in devoting a significant part of their budgets to their armed forces for national self-defense. For evidence of this, we only need to look at the conflict in Ukraine, which was the result of an unprovoked attack by Russia.

Still, legitimate questions can be raised as to how much is enough. The US spends almost three times more than China does on its military and ten times more than Russia. Among peer democracies, the combined spending of the UK, Germany, France, South Korea, Japan, Italy, Australia, Canada, Spain, and the Netherlands (who have 10 of the 20 top military budgets in the world), adds up to about $400 billion, which is still less than half the US military budget. This leads to an obvious why-question: Why does the US spend so much more on its military than any of its peer democracies, as well as its most powerful international rivals (China and Russia)?

Why-questions also pop up when looking at the area of “Societal Safety and Security.” Here, the US again ranks far behind all peer democracies, but is in the middle of the pack on a global basis (between Bangladesh and Liberia). This is mostly due to two factors: a high homicide rate and the highest incarceration rate in the world at 629 per 100,000 people, which equals more than 2 million people in prison. The US has about 300,000 more people in prison than the country with the second highest number of prisoners, China. China, though, has four times the population of the US; thus, with 1.69 million imprisoned people, its incarceration rate is much lower than the US (Fair and Walmsley 2021).

As for peer democracies, in Canada, the prison population rate is 104 per 100,000 people; in Japan, the rate is extremely low at only 37; in South Korea and Taiwan, 105 and 219 respectively; in Norway, it’s a scant 56; and in Western Europe more generally, only France has a prison population rate above 100 (at 119). The story for homicides is much the same. The GPI notes that, in 2022, the “United States recorded the fourth largest overall increase in its homicide rate [among all countries], which is now above six per 100,000 people and more than six times higher than most Western European countries” (Institute for Economics & Peace 2023). More specifically, the US murder rate was 6.52, which was the 28th highest in the world. In peer democracies, none had a murder rate over 2.0 and most had a rate of less than 1.0. The lowest in the world was Japan at 0.2. This leads to a simple why-question: Why is the US such an outlier compared to its peer democracies when it comes to murders and incarceration?

Again, I will address the why-questions posed in this section as this book unfolds. For now, I will simply reiterate that the outcomes reflect a political process based conscious policy decisions. I already noted that military spending is a direct reflection of decisions that state actors make and debate. But the same is largely true for incarceration rates, although criminal laws that lead to imprisonment are mostly made at the level of individual states in the United States. Nonetheless, the biggest driver of high imprisonment in the United States are drug laws, which reflect a drug enforcement regime led by the national government—an enforcement regime, it is important to note, that has had significant international implications as well. As for the high rate of homicides in the US, the issue is admittedly complicated and cannot be reduced to intentional policy decisions. It is clear, however, that “high homicides rates are not inevitable” (Roth 2009, 469) and reflect political, class, and racial (as well as other cultural and institutional) dynamics.

Other Policy-Based Differences

There are myriad other ways in which the US differs from its peer democracies, although the US isn’t always a lone outlier. For example, when it comes to taxes, the US has one of the lowest tax burdens among OECD countries (measured as a percentage of GDP). The OECD average, in 2021, was 34.1% and the figure for the US was 26.6%. But there was one peer democracy, Ireland, with an overall tax burden lower than the US at 21.1% (the other OECD countries were Costa Rica, Türkiye, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico). Tellingly, most US taxes come from personal income, property ownership, and social security contributions (78% of total taxes compared to an OECD average of 57%), while very little comes from taxes on corporate income and profits, which was 5% in 2020; that same year, the OECD average was almost twice as high at 9% (Center for Tax Policy and Administration 2022).

Even more tellingly, many of the largest corporations in the United States often pay no federal taxes at all or had “negative taxes”—in 2020, at least 55 major companies, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, paid $0 in federal corporate income taxes on billions of dollars in profits. Included among the companies were Charter Communications, Duke Energy, HP, Michaels, Nike, Dish Network, Penske Automotive Group, and Archer Daniels Midland; altogether, the 55 companies had $40.4 billion in income, yet had an effective tax rate of -8.6% (Gardner and Wamhoff 2021).

Another relevant policy-based difference can be found in labor policy. A good issue to focus on is collective bargaining. As one set of researchers assert, “the right to collective bargaining is key to solving the crisis of economic inequality. When workers have the ability to bargain collectively with their employers, the division of corporate profits is more equally shared” (Lafer and Loustaunau 2020). Not surprisingly, access to collective bargaining rights varies considerably among peer democracies. The country with the highest level of collective bargaining coverage is Italy at 100% (basically, every single worker in the country). France, Austria, and Belgium are close behind at 96-98%, while Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal, Australia, and Germany are all over 50%.

Again, the United States is last among all of its peers at 11.7%, although South Korea and Japan also have relatively low collective bargaining coverage at 14.8% and 16.9% respectively (all figures from OECD 2019). Importantly, in the United States, the low level of collective bargaining coverage is not primarily because Americans don’t want it. They do. In 2021 Gallup poll, 68% of US adults approved of labor unions, which are the main vehicles used for collective bargaining (Brenan 2021). At the same time, however, 58% of nonunion workers say they’re “not interested at all” in joining a union, so (again) we have a fairly gray picture. It is likely, though, that intense efforts by corporations plays a role in the high proportion of nonunion workers who aren’t interesting in joining a union, a point that will be addressed separately.

While labor rights will be discussed in more depth in Chapter 6, before moving on, it is worth highlighting one additional comparative analysis of labor rights. While admittedly worker-centered, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) publishes an annual “Global Rights Index” (GRI) measuring worker rights around the world in general but primarily focusing on the “worst countries for workers.” While the US is not among the worst countries for workers it is among the worst of its democratic peers. According to the GRI, the US, the UK, and Greece all engage in “Systematic violations of (worker) rights,” which means that governments and/or companies “are engaged in serious efforts to crush the collective voice of workers, putting fundamental rights under threat.” This puts the US in the company of Chad, El Salvador, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, and Vietnam, among a total of 41 countries.

Notably, a single peer democracy, South Korea, is in a lower category, which is labeled, “No guarantee of rights.” (See Box 2.2 for more discussion of South Korea.) This means it is one of the worst countries in the world to work in according to the GRI. In contrast, the “best rating” for workers are all peer democracies: Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Norway, and Sweden. Most other peer democracies—France, Japan, New Zealand, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Portugal, Switzerland, and Taiwan—fall into the next “best” category (“Repeated violations of rights”), while the three remaining peer democracies—Australia, Belgium, and Canada, occupy the middle category in which there are “regular violations of rights” (International Trade Union Confederation 2023).

Box 2.2 A Slightly Closer Looker at South Korea

South Korea has relatively little racial diversity and thus no deep racial divisions within the native population, although over the past several decades, the country has experienced significant immigration. Despite the rise in immigration, it is evident that the race and racism have played little to no role in putting South Korea into a “lower category,” relative to the United States, in terms of labor policy and rights. So, how can we explain the fact that corporate class power, at least at first glance, seems stronger in South Korea than in the US? To adequately answer this question might require a separate chapter. A short answer, then, will have to suffice. And the short answer is this: From the establishment of South Korea (the official name is the Republic of Korea) in 1948, a handful of firms led by particularly ambitious and capable entrepreneurs, were able to take advantage of the chaotic economic and political environment to build up their businesses quickly.

Equally important, in the 1960s, a former military officer, who was part of a coup that took control of the government, embarked on an intense industrialization drive. To achieve his goals, the new leader heavily favored already established, family-owned firms, providing them with huge subsidies, protection from foreign competition, and the like. As a result, these firms—known as chaebol—grew exponentially fast. The very quickly came to utterly dominate the entire economy. This economic domination was particularly pronounced from the 1970s through the 1990s, but even in 2021, the 10 largest chaebol—which includes Samsung, Hyundai, LG, and CJ—accounted for almost 60% of South Korea’s GDP. The government’s early reliance on the chaebol led to a “symbiotic relationship,” which critics have argued, has fostered a culture of corruption. As one Korean professor put it, “Asking for money from chaebol executives in return for political favors was considered quite normal until very recently” (cited in Albert 2018).

American Democracy in Comparative Perspective

Examining specific policy-based areas is a necessary part of seeing how the US differs from its democratic peers. However, a “big picture” perspective is also useful. One way to get this big picture perspective is to address the question, “What is the overall quality of American democracy relative to its peers?” More to the point, is the US—as most Americans are taught or socialized to believe—the greatest democracy in the world? Keep in mind, saying that the US is the greatest “democracy” in the world is not the same as saying the US is the greatest country on the planet.

The two assertions generally get conflated, in part because many Americans associate being great with having great or preponderant economic, military, and political power. If the question is about material and even immaterial (cultural and ideological) power, the US certainly checks all the boxes. Even among scholars, there has been general agreement that the US achieved a hegemonic position after the end of World War 2 and held that position at least until the 1970s to 1980s. (The term “superpower” is similar to hegemon. Basically, a hegemon—as defined in the context of international relations—is not only a state with largely unrivaled military and economic power within its sphere of influence,[10] but also a state that has the capacity and will to assume the preeminent leadership position in global affairs, which means using its resources to build and sustain or underwrite the system it rules.) Today, there is general consensus that is US is no longer the hegemon. Yet, most scholars would nonetheless agree that, strictly in terms of material and especially military capabilities, the US remains the single most “powerful” state.

If, however, the focus is solely on the quality of democracy, the US falls short and, in some cases, far short of most of its democratic peers. Consider, on this point, that the US was not, by definition, even a democracy until, minimally, the early 20th century with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1919, which granted suffrage to (white) women. Until that point, at least half the entire population was denied the right to vote in national elections. If you find this assertion difficult to accept, simply ask yourself the question, “Can a country be democratic if more than half the population is not allowed to vote?” Some observers, moreover, persuasively argue it was not until 1965, with the passage of the Voting Rights Acts, that the United States finally achieved a core criterion of democracy, namely, universal and equal suffrage. Here is how one writer explains it:

It’s not that the United States wasn’t democratic at all before then [1965]. A lot of people could vote, particularly after the 19th Amendment granted suffrage to women (though in practice Black women in the South were still denied the vote). Politicians were regularly elected. But before the Voting Rights Act, Black citizens in the South were excluded from voting. In federal elections, Southern states were effectively herrenvolk democracies, a quasi-democratic system in which only a certain racial or ethnic group is allowed to vote or participate in the government. But at the state level, those Southern states weren’t really democracies at all, many experts say, but rather single-party authoritarian regimes. Opposition politicians and parties couldn’t win power in state governments even if they were white (Taub 2023).

With all this in mind, where does the US stand in relation to its democratic peers in the first part of the 21st century? While it is difficult to provide a definitive assessment, there are several analyses available. One well-respected organization, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), which is a sister company to The Economist news magazine, produces an annual Democracy Index. In 2022, the EIU placed the United States in the category of a “Flawed democracy.” Except for Portugal, Greece, and the Czech Republic (which still had better overall scores than the US), all other peer democracies fell into the category of “Full democracy.” A flawed democracy it still democratic in that it has free and fair elections and generally respects basic civil liberties and rights. However, as the EIU describes it, “there are significant weaknesses in other aspects of democracy, including problems in governance, an underdeveloped political culture and low levels of political participation” (Economist Intelligence Unit 2023).

In another index produced by Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), the US fares better. V-Dem relies primarily on expert judgement to assess key features of democracy, especially those that are not directly observable. For example, the existence of a law that provides oversight by, say, the legislative branch of government over the executive branch is easy to observe; less easy is the extent to which the legislature actually does so. In the V-Dem analysis, experts qualitatively assess the role that legislatures play in real life. The result is an ostensibly more nuanced index. For 2022, V-Dem’s Democracy Report still placed the United States behind most peer democracies, although not at the bottom of the list (for “liberal democracies” [11]).

According to V-Dem, the US is well behind such countries as Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Switzerland, New Zealand, Belgium, Ireland and Australia (and a few others), but tied with Portugal and Canada and slightly ahead of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Austria (V-Dem 2023). There are other analyses, too, the most well-known of which is Freedom House. In its 2021 analysis, the US was ranked 56th out of 194 countries and territories, tied with South Korea, but far behind all other peer democracies.

Thus, whichever index is used, it is quite certain the US is not the “greatest democracy in the world,” and it’s abundantly clear that the US is not even among the world’s strongest democracies. Box 2.3 provides a summary of the rankings and scores from the three sources discussed in this section.

Box 2.3 Where America’s Democracy Ranks (US and Selected Peer Democracies) |

|||

| Country | EIU Democracy Index (Rank/Score), 2022 | V-Dem Democracy Report (Rank/Score), 2022 | Freedom House (Rank/Score), 2021 |

|

Denmark |

6 (9.28) | 1 (0.89) | 10 (97) |

|

Sweden |

4 (9.39) | 2 (0.87) | 1 (100) |

|

Norway |

1 (9.81) | 3 (0.86) | 1 (100) |

|

Finland |

5 (9.29) | 10 (0.82) | 1 (100) |

|

Canada |

12 (8.88) | 24 (0.74) | 7 (98) |

|

Australia |

15 (8.71) | 11 (0.81) | 11 (97) |

|

Japan |

16 (8.330 | 27 (0.73) | 14 (96) |

|

Germany |

14 (8.8) | 12 (0.81) | 19 (94 |

|

United Kingdom |

18 (8.28) | 20 (0.77) | 22 (93) |

|

South Korea |

24 (8.03) | 28 (0.73) | 56 (83) |

|

United States |

30 (7.8) | 23 (0.74) | 56 (83) |

| Sources: Economic Intelligence Unit (2023), V-Dem (2023), Freedom House (2021) | |||

A Closer Look at the World’s “Best Democracy”: Norway

The question of how democratic the United States is one that I will address throughout the remainder of this book. In the meantime, though, it would be instructive to consider what makes for a “great” democracy. If you look at Box 2.2, you’ll see that Norway is ranked first on two of the indexes (EIU and Freedom House) and third on the V-Dem list. Overall, then, its the gets the “award” for the world’s strongest (greatest?) democracy. On the surface, there is not much that distinguishes Norway from other democracies. It has free and fair elections; a competitive multiparty system; a strong framework of civil rights and liberties, which extends to minority groups; an independent media; a strong rule of law; and so forth.

However, unlike the US, a strong effort has been made to minimize the role of money in the electoral process. Political advertising is extensively regulated, which includes ensuring that political contributions are transparent to the public (laws require that donors be made public). In addition, while candidates and parties are free to buy print and social media advertisements, they are prohibited from doing so on television and radio. Political parties are also funded—typically between 60% and 80% of total funds—primarily by public grants (Hagen, Bach, and Jahn 2022).

The issue of money in politics raises underscore another distinctive element of Norwegian society, one that is not directly related to the definitional aspects of democracy, but which potentially has a major impact on the quality and practice of democracy. To wit, in Norway, state ownership of commercial enterprises is quite high. In 2014, the Norwegian state controlled more than one-third of the total value of the companies listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange and owned or partly owned five of the seven largest listed companies (Lie 2016); the state also operates the two largest non-listed companies in the country (Economist 2013).

Moreover, fully one-third of all workers in Norway work for the state. Importantly, a significant part of the Norwegian economy is based on oil and gas production—a major source of which was first discovered in 1959 (although the first well was not drilled until 1966). Even more importantly, rather than allowing private companies to take sole ownership of these valuable natural resources, the Norwegian government proclaimed sovereignty over the oil and gas reserves to ensure that profits from the wells went into the public pocket rather than entirely into private hands (McKay 2019). With profits from it control of oil and gas production, the Norwegian government has been able to build the largest sovereign wealth (or state-owned investment) fund in the world, which was valued at $1.4 trillion in 2021 (Lars 2021).

The state’s direct and sizable ownership of key businesses in the country, its status as the largest employer, and its control of a massive sovereign wealth fund combine to reduce the size and influence of the corporate class, as well as of the monied class. Of course, so much state-control of profit-making enterprises could lead to a high degree of corruption and a concomitant lack of trust in the government, but corruption is Norway is exceptionally low, while trust in government is very high—in 2021, 77% of the country’s population reported trusting the government (OECD 2022).

According to Transparency International, which produces the most widely used global corruption ranking, Norway is among the “cleanest” or least corrupt countries on the planet—in 2022, Norway was rated as the 4th cleanest country out of 180 (Transparency International 2023). At the same time, Norway’s lower-income and middle classes are relatively unified, as one scholar argues, based on the country’s long-standing anti-hierarchical moral culture, which has had the “effect of discouraging boundary drawing towards others based on culture, education, and status” (Skarpenes 2021, 169).

The relative unity of the lower-income and middle classes suggests that they are a strong political force relative to the corporate and monied classes in Norway. As a result, while the corporate class can and does influence national policy in Norway, the government is responsive to the lower-income and middle classes, who often use trade unions as a primary vehicle to directly express their political preferences. The role that trade unions play, in fact, reflects an institutional feature of Norwegian politics that political scientists refer to as corporatism. The term “corporatism,” I need to emphasize, does not mean corporate dominance; instead, it refers to a political system in which key societal actors (e.g., organized business interests and unions) and the government are essentially incorporated into an integrated body (or “corpus”). The upshot is that Norway has a political system that is not dominated by any one class or set of actors.[12]

Obviously, in a few paragraphs I cannot provide an adequate examination of Norwegian democracy. Nor is the brief discussion of Norway meant to imply that it provides a model that other countries, including the US, could emulate. For, despite basic similarities, every peer democracy (and every country) has developed within a specific context that a creates unique or idiosyncratic path, which, in some cases, cannot be replicated. Still, the foregoing discussion usefully highlights the significance of class and power.

In Norway, race plays less of a role, if only because the country “does not have history of race-based slavery or legal racial segregation, and the Norwegian state has not been a colonial power” (Kyllingstad 2017, 319). This doesn’t mean there is no racial tensions in Norway. There are. Over the past half-century, steady immigration has led to some backlash against immigrants—16% of the people in Norway are immigrants or are Norwegian-born children of immigrants, about half of whom come from Asia, Africa, and Latin America (cited in Kyllingstad 2017). Notably, Norway also suffered from one of the worst racially motivated mass killings in history, when Anders Behring Breivik killed 77 people in 2011 (in two separate attacks). Although his victims were mainly white Norwegians, his self-proclaimed motive was to fight multiculturalism and the “Islamization” of Norway, which he blamed on the governing Labour Party—thus, his main target was a Labour Party youth summer camp, which was being held on a small island (for additional discussion, see Hemmingby and Bjørgo 2018). Nonetheless, race/racism was never deeply embedded into Norwegian society in the same way it was in the United States.

A Very Brief Conclusion

This chapter has covered a lot of ground but, in important ways, it hasn’t actually covered much ground at all. This is because there are literally too many issues and too many comparisons—including deeper and more systematic comparisons—that I could not fit into the space of a single chapter. The goal of this chapter, however, was primarily to provide a broader perspective, even if limited, that is generally entirely missing from conventional textbooks on American politics.

Having a broader and, more specifically, comparative perspective is not only “eye-opening,” especially when what you see is surprising, but also when it pushes you to consider why American politics and American democracy looks and operates the way it does—although I recognize that I haven’t really focused on the latter point yet. In the following chapters, the focus will turn to and remain on American politics and democracy. A comparative perspective, though, will not be forgotten. When useful and relevant, comparisons will continue to be used both as illustrations and support for the larger argument upon which this book is based.

Chapter Notes

[1] Another set of scholars provide a different take. They argue that, while anger is a relevant factor, “a more complex and multi-faceted sense of malaise is at the origin of the rise in populism” (Ali, Desmet, and Wacziarg 2023).

[2] The criteria used by the RoW project to classify a country as democratic are similar to the definition of democracy used in this book. Specifically, the Varieties of Democracy project, which produces the RoW index, defined a country as (minimally) democratic when “ … citizens have the right to choose the chief executive and the legislature in meaningful, free and fair, and multi-party elections” (Herre 2021).

[3] Figures are based on estimates by the International Monetary Fund (IMF 2023).

[4] Interestingly, though, Jamaica does have a system of free health care for all citizens (which began in 2008), although it suffers from serious funding issues, leading to a lack of hospital beds, staffing shortages, and low salaries for health care professionals. For one (admittedly anecdotal) view, see Pryce (2021).

[5] A systematic comparison would not require writing an entire book but would also require a focus on just a few key areas. An example of this is a book written by John Bowman, Capitalisms Compared: Welfare, Work, and Business (2014). In his book, Bowman compares the US to only two other countries, Germany and Sweden and focuses on five policy issues: health policy, pension policy, family policy, labor policy, and corporate governance.

[6] In China, for instance, the state owns many of the country’s largest corporations, which are also among the largest corporations in the world. In addition, while there is a thriving private sector in China, even the richest CEOs understand that they are subject, at times, to direct state control—in one well-known incident, the billionaire CEO of Alibaba, China’s version of Amazon, essentially disappeared for several months after making a speech that was critical of China’s financial establishment; it was clear that he angered China’s leaders and was made an example of as he not only disappeared from public view, but much of his assets were stripped away. In Venezuela, under the former President Hugo Chavez, property right became, as one analyst put it, “basically what the Government want them to be …” (Thompson 2017).

[7] The term “state” is similar to the more commonly used term “government.” The two terms are often used interchangeably, which is generally fine especially when referring to national governments. However, for political scientists, there is a clear distinction. A state is a centralized political apparatus that exercises sovereign authority over the entire population within a given territory. A government is also a political authority responsible for passing, implementing, and (usually) enforcing laws, but governments are by and large agents of a state or states. One easy way to understand this is to recognize that, in any given state, there are multiple governments, from city governments to county governments, tribal governments, provincial governments, and so forth. There are also governments at the international level, the best example of which is the European Union.

[8] There are several measures of political stability, one of which is based on the “likelihood of a disorderly transfer of government power, armed conflict, violent demonstrations, social unrest, international tensions, terrorism, as well as ethnic, religious or regional conflicts.” According to this definition, which is available on the GlobalEconomy website (2021), the US ranks in the middle of all countries, but lower than all of its peer democracies.

[9] The Index is designed to measure “well-being” across countries by assessing 11 topics that the OECD has identified as essential in the areas of material living conditions and quality of life. The 11 areas are housing, income, jobs, community, education, environment, civic engagement, health, life satisfaction, safety, and work-life balance. For details see OECD (2020).

[10] I write “sphere of influence,” since a hegemon doesn’t have to dominate the entire world. During the Cold War, in particular, the US dominated the so-called “Free World” (i.e., basically, all those countries that had adopted a market-based economic system, some of which were decidedly unfree, as they were governed by oppressive authoritarian states), which was its sphere of influence, while the Soviet Union dominated the so-called “Communist World.”

[11] V-Dem’s methodology is complicated; moreover, it operates on the assumption that there is not just one type of democracy but rather multiple varieties—the “V” in V-Dem stands for “varieties.” V-Dem measures for different varieties of democracy, “Liberal,” “Participatory,” “Deliberative,” and “Equalitarian.” For further discussion, see Coppedge (2023).

[12] For more discussion of corporatism in Norway, see Christiansen (2018) and Mailand (2009).

Chapter References

Albert, Eleanor. 2018. “South Korea’s Chaebol Challenge.” Council on Foreign Relations: Backgrounder, <ay 4. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/south-koreas-chaebol-challenge.

Ali, Omer, Klaus Desmet, and Romain Wacziarg. 2023. “Does Anger Drive Populism?” NBER Working Paper Series. https://www.nber.org/papers/w31383#fromrss

Bowman, John R. 2014. Capitalisms Compared: Welfare, Work, and Business. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Brenan, Megan. 2021. “Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point since 1965.” Gallup, September 2. https://news.gallup.com/poll/354455/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspx.

Center for Tax Policy and Administration. 2022. “Revenue Statistics 2022 – the United States.” OECD Revenue Statistics 2022. https://www.oecd.org/tax/revenue-statistics-united-states.pdf.

Chen, Lanhee. 2018. “What’s Wrong with Government-Run Healthcare?” PragerU (YouTube), October 15. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEzO2KoJq2A.

Christiansen, Peter Munk. 2018. “Still the Corporatist Darlings?” In The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics, edited by Peter Nedergaard and Anders Wivel, 36-48. London and New York: Routledge.

Coppedge, Michael. 2023. V-Dem’s Conceptions of Democracy and Their Consequences. V-Dem Institute Working Paper. https://www.v-dem.net/media/publications/wp_135.pdf.

Dincecco, Mark, and Yuhua Wang. 2022. “State Capacity in Historical Political Economy.” In Oxford Handbook of Historical Political Economy

Economist. 2013. “The Rich Cousin: Oil Makes Norway Different from the Rest of the Region, but Only up to a Point.” Economist, January 31. https://www.economist.com/special-report/2013/01/31/the-rich-cousin.

Economist Intelligence Unit. 2023. Democracy Index 2022. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited.

Fair, Helen, and Roy Walmsley. 2021. World Prison Population List. 13 ed. London: Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2017. 2017 Crime in the United States. In Uniform Crime Reports: FBI.https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/expanded-offense.

Freedom House. 2021. Freedom in the World 2021: Democracy under Seige. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House.

Freedom House. 2023. “Israel.” Freedom in the World. https://freedomhouse.org/country/israel/freedom-world/2023.

Gardner, Matthew, and Steve Wamhoff. 2021. “55 Corporations Paid $0 in Federal Taxes on 2020 Profits ” ITEP Report, April 2. https://itep.org/55-profitable-corporations-zero-corporate-tax/.

Gordon, Damion. 2018. “Is Jamaica a Failed State? An Academic Perspective.” The Gleaner, February 9. https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/focus/20180211/damion-gordon-jamaica-failed-state-academic-perspective

Gould, Elise, and Jori Kandra. 2022. “Inequality in Annual Earnings Worsens in 2021.” Economic Policy Institute, December 21. https://www.epi.org/publication/inequality-2021-ssa-data/.

Gunja, Munira Z., Evan D. Gumas, and Reginald D. Williams II. 2023. “U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2022: Accelerating Spending, Worsening Outcomes.” Commonwealth Fund, January 31. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2022.

Hagen, Kåre P, Tobias Bach, and Detlef Jahn. 2022. “Norway Report.” In Sustainable Governance Indicators 2022. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Hemmingby, Cato, and Tore Bjørgo. 2018. “Terrorist Target Selection: The Case of Anders Behring Breivik.” Perspectives on Terrorism 12 (6):164-176. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26544650

Heritage Foundation. 2022. “Property Rights – Country Rankings.” The GlobalEconomy.com. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/herit_property_rights/.

Herre, Bastian. 2021. “The ‘Regimes of the World’ Data: How Do Researchers Measure Democracy?” Our World In Data, December 2. https://ourworldindata.org/regimes-of-the-world-data.

Herre, Bastian. 2022. “The World Has Recently Become Less Democratic.” Our World in Data, September 6. https://ourworldindata.org/less-democratic.

Holden, Stephen. 2015. “Review: ‘Where to Invade Next,’ Michael Moore’s Latest Documentary.” New York Times, December 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/23/movies/review-where-to-invade-next-michael-moores-latest-documentary.html

IMF. 2023. World Economic Outlook Database. Washington, D.C.: IMF.https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending.

Institute for Economics & Peace. 2023. “Global Peace Index 2023: Measuring Peace in a Complex World.” Quantifying Peace and its Benefits. http://visionofhumanity.org/resources.

International Trade Union Confederation. 2023. 2032 Ituc Global Rights Index: The World’s Worst Countries for Workers. Brussels: ITUC International Trade Union Confederation.

Kyllingstad, Jon Røyne. 2017. “The Absence of Race in Norway?” Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95:319-327

Lafer, Gordon, and Lola Loustaunau. 2020. “Fear at Work: An inside Account of How Employers Threaten, Intimidate, and Harass Workers to Stop Them from Exercising Their Right to Collective Bargaining.” Economic Policy Institute, July 23. https://www.epi.org/publication/fear-at-work-how-employers-scare-workers-out-of-unionizing/.

Lars, Erik Taraldsen. 2021. “Norway’s $1.4 Trillion Wealth Fund Takes Aim at Oil Companies.” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/8/20/norways-1-4-trillion-wealth-fund-takes-aim-at-oil-companies.

Lie, Einar. 2016. “Context and Contingency: Explaining State Ownership in Norway.” Enterprise & society 17 (4):904-930

Mailand, Mikkel. 2009. Corporatism in Denmark and Norway—yet Another Century of Scandinavian Corporatism? https://faos.ku.dk/pdf/artikler/videnskabelige_artikler/2009/Corporatism_in_Denmark_and_Norway_0109.pdf.

Maruyama, Mayumi. 2022. “Japan Had Only One Gun-Related Death Reported in 2021.” CNN World, July 8. https://edition.cnn.com/asia/live-news/shinzo-abe-japan-pm-collapses-nara-07-08-22-intl-hnk/h_c48b3ef15abb75698e1540ad14b7c497.

McKay, Andrew. 2019. “Black Gold: Norway’s Oil Story.” Life in Norway, October 2. https://www.lifeinnorway.net/norway-oil-history/.

Moore, Michael. 2015. Where to Invade Next. United States: Dog Eat Dog Flims and IMG Films (distributed by Neon).

Newzoo. 2022. “Top Countries/Markets by Game Revenues.” Newzoo. https://newzoo.com/resources/rankings/top-10-countries-by-game-revenues.

OECD. 2019. Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Wor. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. 2020. How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-Being. Paris: OECD.

OECD. 2022. Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in Norway: Building Trust in Public Institutions. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, J. Baxter Oliphant, and Anna Brown. 2017. “Views of Guns and Gun Violence.” Pew Research Center, June 22. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/06/22/views-of-guns-and-gun-violence/#ease-of-access-to-illegal-guns-seen-as-the-biggest-contributor-to-gun-violence.

Powell, Alvin. 2016. “The Costs of Inequality: Money = Quality Health Care = Longer Life.” Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2016/02/money-quality-health-care-longer-life/.

Pryce, Tomoya. 2021. “Truth Behind Jamaica’s Healthcare System: A Nurse’s Perspective ” The Gleaner, September 14. https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/commentary/20210914/tomoya-pryce-truth-behind-jamaicas-healthcare-system-nurses-perspective

Rice, Thomas, Pauline Rosenau, Lynn Y. Unruh, and Andrew J. Barnes. 2020. United States: Health System Review, Health Systems in Transition. UN City: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Rico, Guillem, March Guinjoan, and Eva Adnuiza. 2017. “The Emotional Underpinnings of Populism: How Anger and Fear Affect Populist Attitudes.” Swiss Political Science Review 23 (4):444-461

Roth, Randolph. 2009. American Homicide. Cambridge, Mass.: Belnap Press of Harvard University.

Schneider, Eric C., Arnav Shah, Michelle M. Doty, Roosa Tikkanen, Katharine Fields, and Reginald D. Williams II. 2021. “Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly.” Commonwealth Fund, August 4. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/aug/mirror-mirror-2021-reflecting-poorly.

Skarpenes, Ove. 2021. “Defending the Nordic Model: Understanding Themoral Universe of the Norwegian Working Class.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 8 (2):151-174.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/23254823.2021.1895857?needAccess=true&role=button

Taub, Amanda. 2023. “When Did the U.S. Become a Democracy?” New York Times, July 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/05/world/us-democracy-voting-rights-act.html

The GlobalEconomy.com. 2021. “Political Stability – Country Rankings.” The GlobalEconomy.com. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/wb_political_stability/.

Thompson, Philip. 2017. “How Weak Property Rights Contribute to Venezuela’s Crisis.” Property Rights Alliance, September 5. https://www.propertyrightsalliance.org/news/how-weak-property-rights-contribute-to-venezuelas-crisis/.

Transparency International. 2023. Corruption Perceptions Index. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022.

V-Dem. 2023. Democracy Report 2023: Defiance in the Face of Autocratization. Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg.