1 An Introduction to Class, Race, and Power in American Politics

An Overview

Politics is the same everywhere in the world. However, the consequences or outcomes of politics (See Box 1.1 Key Concepts for the definition of politics) are definitely not the same. Some countries, for example, may have a great deal of inequality, poverty, and social violence/crime. Other countries, by contrast, may have comparatively low levels of inequality, limited poverty, and little societal violence and crime. Some countries may also have a comprehensive or universal system of national health care—covering virtually the entire population—or have policies mandating paid parental/maternity leave, paid holidays, tuition-free education from pre-school through university, affordable housing, a full and robust panoply of worker rights and protections, strict regulations on corporate activity, and so on. Others may have only some or even none of these policies.

Given that there are significant differences among countries of all political and economic stripes, but also just among a subset of wealthy democracies (e.g., the US, Canada, countries in the European Union and in Scandinavia, Japan, Australia, and the like), an obvious question arises, namely, “What explains the difference in outcomes?” Most broadly, this book aims to answer that deceptively simple question. As the main title of this book suggests, a big (but not only) part of the answer lies in understanding the significance of class and race—two contentious terms—and how these two factors, as well as the relationship between them, shapes the distribution and exercise of power within countries. Power, in turn, determines, to use one extremely dated but still relevant portrayal of politics, “Who gets what, when, how” (Lasswell 1936). (There will be a more in-depth discussion of power below.)

The primary focus of this book is politics in the United States or just American politics. As the title also suggests, however, our examination of American politics will be done from a comparative perspective. There are a couple of basic reasons for this. The first is to simply show differences and similarities among countries; this type of comparative perspective is useful in identifying common processes that affect all or most countries but also in highlighting the variety of paths countries take. In addition, a comparative perspective helps us understand the possibilities for change. This is because it’s easy to assume that the way things are (in the US or any other country) is the way things always have been and always will be, which is to say we often believe that there are no viable alternatives to the current reality. For instance, if, as some critics of American politics assert, the contemporary political system in the US is dominated by the wealthiest individuals and corporations (i.e., “the elites”), there may be a general sense that nothing can be realistically done to fundamentally undercut or effectively challenge that domination.

Ordinary citizens may not be happy living in a country where, for all intents and purposes, the wealthiest rule—indeed, they may be quite angry (or, conversely, extremely envious)—but they may also feel powerless to do anything about it. Alternatively, ordinary citizens may be complicit, both intentionally and unintentionally, in reinforcing an ostensibly democratic political system that primarily caters to the needs and interests of the ultra-wealthy rather than in supporting a system that supports their own needs and interests. Yet, by adopting a comparative perspective, it becomes possible to see, in concrete or real-world terms, that different political and economic arrangements are possible (which is not to say they are necessarily preferable). Merely seeing differences, however, is not the same as understanding why those differences exist or how they were achieved and are sustained over time. A comparative perspective, then, is more than just pointing to differences; it also involves using comparisons to help explain and better understand political outcomes.

Importantly, adopting a comparative perspective doesn’t require a comparison between the United States and other countries. It is perfectly reasonable and even preferable to do “sub-national” comparisons. Sub-national, as the term implies, refers to anything below the national level. More concretely, a sub-national comparison may involve comparing one city to another (e.g., comparing Los Angeles to New York or Chicago or Atlanta), or comparing one state to another. Chapter 7 does the latter. That is, Chapter 7 revolves around a comparison of California and Texas. Such comparisons, it’s important to emphasize, are not designed to show that one state is “better” or “superior” to another. It’s clear that preferences for one or the other states (or others) is subjective. Instead, the comparison has the same general intent as international comparisons, namely, to both see that significantly different political outcomes are possible within the United States, and also to better understand the reasons behind these different outcomes.

Box 1.1 Key Concepts: Politics

Politics, in the American context, is often reduced to partisan disagreements, that is, with disagreements or struggles between the Democratic and Republican Parties. While such disagreements are certainly political, it’s important not to think of politics as only or primarily involving partisan debates or issues. Nor is politics just about governments do, which is another common way of thinking about the term. Instead, politics should be understood more broadly. Here’s one definition offered by Adrian Leftwich (2004): “Politics is not a separate realm of public life and activity. On the contrary, politics comprises all the activities of co-operation and conflict, within and between societies, whereby the human species goes about organizing the use, production and distribution of human, natural and other resources in the course of production and reproduction of its biological and social life” (103).

There are, he continues, three essential interactive ingredients of politics: “people (commonly with different interests, preferences and ideas); resources (almost always scarce in that there will not be enough of whatever it is—whether land or time or opportunity—for everyone to get everything that they want; and power (the capacity to get one’s way—whether by force, status, age, tradition, gender, wealth, influence or authority)” (italics in original: 104).

In Leftwich’s definition, politics includes partisan disagreements and activities directly involving governments or states, but it also goes well beyond those two elements. It can include, for example, the interactions between workers and employers (or between workers and workers and employers and employers); the myriad activities of corporations, both inside and outside the borders of a country; the relationship between different racial and ethnic groups; the work of universities, scientists, and researchers; and so forth. Importantly, too, Leftwich does not limit politics to conflict; cooperation or collaboration is also political.

Race, Class, and Power: Key Concepts

At the outset, class, race, and power were emphasized as key to understanding and explaining American politics. This is not to suggest that other factors do not matter. In the United States and in many other countries, religion (and culture more generally), gender, age (i.e., generational differences), and so on are all relevant intersectional factors that shape politics. Accordingly, these factors should not be ignored. Nonetheless, the central argument in this book is that class and race are not only the primary driving forces in American politics, but also that their unique interaction in the American context has played a large role in setting the US apart from other wealthy democracies.

As was suggested above, the US is different. It is the richest country in terms of GDP (gross domestic product) and the most militarily powerful (the US military budget in 2023 was $877 billion—more than three times higher than the next country on the list, China, and ten times higher than Russia). The US is arguably the most technologically dynamic country on the planet—being home to Apple, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Dell, IBM, Tesla, etc.—as well as being one of the most ethnically diverse. But the US also stands out among other wealthy democracies in a number of other, perhaps less estimable, ways. Here is just a very selective list of some of the ways the US is “special”:

- Unlike its wealthy, democratic peers (and most of the world), the US does not have a system of universal healthcare; partly as a result, the US also ranks very low in average life expectancy.

- The US has a very low level of unionization (International Labor Organization 2022) and among the weakest labor laws when it comes to union recognition and collective bargaining rights (Logan 2009).

- The US incarcerates more of its population than any other democratic country in the world, as well as almost all non-democratic ones (Wiadra and Herring 2021).

- Among the 37 OECD[1] countries, the US has the fifth highest level of income inequality, and the highest among wealthy democracies (the four countries with high level of inequality are all relatively poor: Bulgaria, Turkey, Mexico, and Costa Rica (OECD 2015).

It is fair to say that these differences don’t just happen. They, instead, are the result of specific political processes, which, to repeat the main argument of this book, are driven by two dominant factors or forces: Class and race. It’s necessary to consider the meaning of these two terms. We’ll begin with a focus on class.

What is Class?

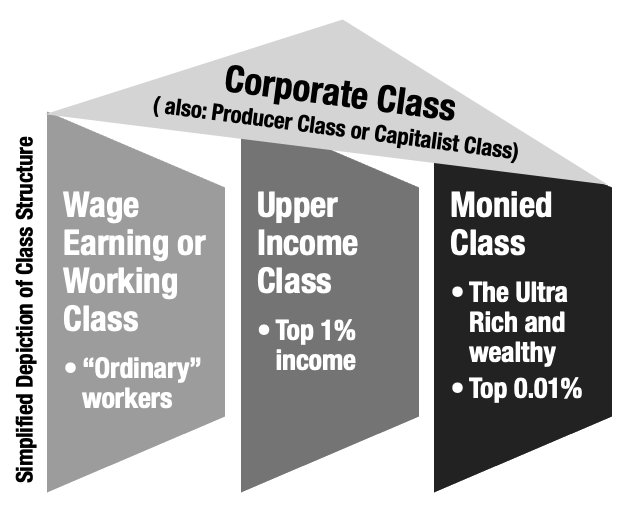

Class does not just refer to economic divisions based on wealth and income,[2] such as the division between those with limited or modest economic resources and those with huge incomes and immense (accumulated) wealth. Still, in the news and everyday conversations, income and wealth are most often used as the basis for dividing societies into multiple “classes”: the lower (or working), middle, upper-middle, and upper classes. That is not an unimportant division, but in a market-based or capitalist economy, there is a more basic division over those who “work for a living” and those who own or control the companies that produce goods and services, i.e., the “producers.” Admittedly, this binary division between workers and producer may seem quite crude in that, in modern market-based economies, there are huge differences between, say, a minimum wage worker in a fast food restaurant and a hedge fund manager or between a janitor and an aerospace engineer. They all work for a living (that is, they earn a salary paid by their employers), but their socioeconomic positions and standards of living are hardly the same.

Thus, it is reasonable to include to at least one more class division between lower-paid workers and well-compensated ones, the latter of whom can be referred to as the upper (income) class. Even more, though, among those with high incomes and wealth, there are vast differences. The income required to be in the top 1%, in 2022, was about $570,000; with respect to net worth (or wealth), the figure was just under $11 million. That same year, however, LeBron James was the highest paid American athlete with earnings of $121.2 million (Knight 2022). Among actors or entertainers, Tom Cruise earned more than $100 million for just one movie, “Top Gun: Maverick” (Guerrasio 2022), and MacKenzie Scott, former wife of Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, was worth $24.4 billion in 2023 (LaFranco and Peterson-Withorn 2023). The upshot is clear: These individuals are also in a “class of their own,” which I will simply refer to as the monied class to distinguish them from the “ordinary” upper class.

Even while accepting that wage differentials can be and are extremely important in the lives of individuals, those who solely work for a living (i.e., depend on their jobs as their primary or sole source of income), regardless of how high or low their incomes are, share one basic characteristic: They do not exercise direct control over the companies—especially the biggest and most powerful corporations—that produce goods and services. Economic control, of course, is not divorced from income (and wealth) as those with immense incomes/wealth can assume control of productive enterprises by building them from the ground up or, more expeditiously, by acquiring them either by gaining a controlling interest through stock purchases or by buying them outright. For example, LeBron James owns or partly owns five companies: Fenway Sports Group, Springhill Entertainment, Uninterrupted, Blaze Pizza, and Ladder (Cunningham 2022).

Generally speaking, though, those with the financial resources to buy a large company already exercise direct corporate control, as is the case with Elon Musk, who owned two larger companies—Tesla and SpaceX (as well as two smaller start-ups)—prior to making an “all-cash” offer of $44 billion to acquire Twitter in 2022. Thus, just as the monied class stands apart from the ordinary upper class, the people who control the largest corporations constitute a numerical tiny but singularly influential class of their own, too, namely the corporate class. The corporate class, in fact, will be a central focus of this book, but before discussing in more detail, a brief discussion of the second key concept, race, is in order.

Defining Race and Racism

In the 1900 US Census, five racial categories were identified: White, Black, Chinese, Indian, and Japanese. Tellingly, over the decades, the racial classifications used in the US Census continually changed—although a big reason for some changes stemmed from increasing immigration from different parts of the world. Nonetheless, by 2020, there were 18 separate “racial” classifications, plus one category labeled, “Some other race”; in addition, those who identified as “White” and “Black or African American” were asked to provide additional information about their origins (see Pew Research Center 2020). What this suggests is that “race” is an ambiguous, fluid, and subjective concept. To scholars and others this is not at all surprising. This is because they have long understood race to be social construction. This said, the view of race as a social construct is, by now, a fairly well-known and even banal point. Still, a basic explanation is in order.

Briefly put, saying that race is a social construction means, first of all, that it is not based on objective factors, such as specific physical or biogenetic traits that definitively differentiate one category of people from another. Instead, the concept of race is unavoidably subjective or intersubjective, which, in the case of the latter terms, merely means that race is basically defined by people and their societies. Second, as a subjective concept, race can be and has been used not only to divide humanity into supposedly distinct groups, but also to create a racial hierarchy wherein racial differences are used to justify differential and usually unequal, discriminatory, and inhumane treatment. One more point: Despite its subjective nature, social constructions are just as real and consequential as the most objective force—just consider all the suffering, misery, oppression, and death that has resulted from the social construction of race.

The creation of racial hierarchies is, to return to the main point, what transforms race into racism, although as one scholar aptly noted, the concept of race necessarily “… includes ‘racism,’ as one is unthinkable without the other …” (Reed 2013). It is easy to assume that race/racism has been around as long as human societies have existed, but it is a fairly recent “invention” arising, at least as a body of thought in which some humans were deemed inherently inferior to others based on skin color, in the late-17th to early-18th centuries. And, as with all inventions, it was created to serve a particular function or role in human society. But it wasn’t until the 19th century that it “acquired the pseudo-scientific reinforcement of biological theories of race” (Brabec 2019, 39). From this perspective, it should be apparent that racism is an ideology. That is, it is a set of beliefs and principles that generally legitimize and form the basis for a connected set of political, social, and economic practices and arrangements.

There are several complex reasons why the concept of race and ideology of racism emerged around 350 years ago, but they can be boiled down, on the one hand, to the rise of wage labor (or a “free labor” class)—which reflected the gradually ascent of capitalism as a dominant and, at the time, new economic system—and the closely connected ascent of an ideology based on equality and freedom. (This book uses a broad definition of capitalism as an economic system in which most everything is commodified—made into a product, including labor—to be bought and sold in a market for profit.) On the other hand, this was also a period that saw the intensification and deepening of two cross-border phenomena mostly controlled by the West: Slavery and colonialism. The two sets of activities were fundamentally at odds.

Consider this famous phrase enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” For the United States, the existence of slavery in this context flatly contradicted what many think of as the soul of America (Dyer 2011)—notably, the same contradiction was at play for other western countries, where colonialism played a much stronger role. Thus, for the US specifically, the contradictory existence of an ideology based on equality and freedom and the practice of slavery—as well as the oppression of slaughter of Native Americans—quite literally required a parallel ideology that made some “men” (people) less than human.

I will have much more to say about race/racism and class later in this chapter and throughout the remainder of the book. For now, though, a discussion of the third key concept in this section—power—is in order.

What is Power and Who Has It?

The significance of class and race in American politics is integrally tied to the issue of power. On this issue, a major premise of this book is that one class—the corporate class or the corporate elite—has the most power. On first glance, this is a seemingly trite statement. But it raises an often unexamined yet very important question, namely, “What does it mean to say that members of the corporate class—or any other actor, from elected government officials and bureaucrats to ordinary citizens—have or do not have power?” The simplest (and admittedly simplistic) answer was provided in Key Concepts, Box 1.1: To have power is to have the capacity to get your way. In addition, and more specifically, having power (with respect to the definition of politics), means having the capacity to influence or even wholly determine how certain resources will be organized, used, produced, and distributed both domestically and on a global basis.

Consider just a few relevant questions: Who determines wages paid to workers? Who determines voting procedures and the rules governing elections? Who determines the type of health care system a country has? Who determines when to use military force against others? Who determines who goes to prison and for what crimes and for how long? Who determines tax rates for individuals and corporations? Who determines laws regarding reproductive rights? Who determines financial, environmental, health, and safety regulations? The list of questions is practically endless, but the general answer is always the same: Those with power.

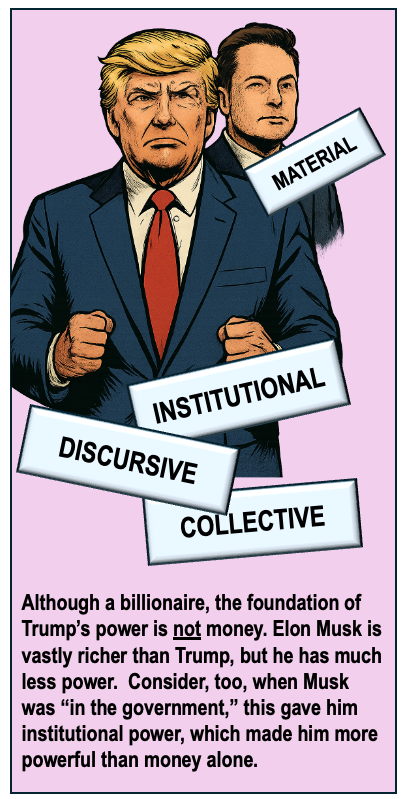

It is tempting to end our discussion of power with the last statement; that would keep things nice and simple. But the issue is much more complicated. Before explaining the complications, though, it would be useful to re-address the common understanding that power is primarily based on material factors, in general, and, bluntly put, having a lot of money more specifically. Indeed, as a professor, when I ask the question, “Who has the most power?” most of the students I teach at my university have the same answer, “The wealthy.” To be sure, wealth or the possession of material resources is an undeniably important source of power, especially when it comes to influencing public or government policy or laws (which is a focus of this book). After all, business organizations and corporations spend tens of millions of dollars on lobbying to directly influence and shape government policy. Very frequently, they get their way, often against the wishes of the general public. In the US, for example, the vast majority of citizens (close to 70% in 2023) want more government action addressing climate change (Tyson, Funk, and Kennedy 2023); yet, government action has been, at best, lacking due, at least in part and perhaps mostly, to intense and money-fueled lobbying efforts by energy companies (InfluenceMap 2019). One easy conclusion or equation to draw from this state of affairs is this: Money = power = political influence.

As a counterpoint to the focus on wealth, though, think about the undeniable power of Donald Trump, both during his presidency and afterwards. It’s true that he is a billionaire (or at least very wealthy) and it’s true that his status as a billionaire played a role in his political success. However, other billionaires have run for office—e.g., Michael Bloomberg, Meg Whitman, Howard Schultz, Tom Steyer, and Ross Perot, to name a few—and either lost or gave up despite their vast wealth, so it’s evident that money does not necessarily equate (in the case of running for elected office) to power. In Trump’s case, his accumulation of power since 2015 likely had little to do, at least concretely, with his wealth. Instead, he became powerful because he convinced tens of millions of American citizens that he represented their interests and concerns better than anyone else. In this sense, Trump’s power was and is largely based on his words and ideas. We can call this discursive power. Conversely, if tomorrow, all his followers stopped believing in and acting on the words and ideas of Trump, his influence in American politics would largely and even completely vanish. He would go back to being a very wealthy but far less powerful individual.

Trump’s power underscores another important point: The large and devoted following the former president has generated since 2015 (when he officially declared his candidacy for president) reflects the collective power of ordinary citizens. In a democracy or, really, any type of political system, including dictatorships, to quote Martin Luther King, Jr., “There is power in unity and there is power in numbers” (cited in Nittle 2017). Collective power—whether exercised by a smaller segment of larger population or by “the people” more generally—must not be discounted or underestimated, especially in the context of a democratic political system; it is, in some respects, the most significant (although often not fully realized) source of power in American politics and in the politics of other countries around the world. That is, when hundreds of thousands, millions, or even tens of millions of people are willing to rise up in a unified and coherent manner, for a sustained period of time, they have a type of power that doesn’t primarily rely on and stands apart from wealth or material good.

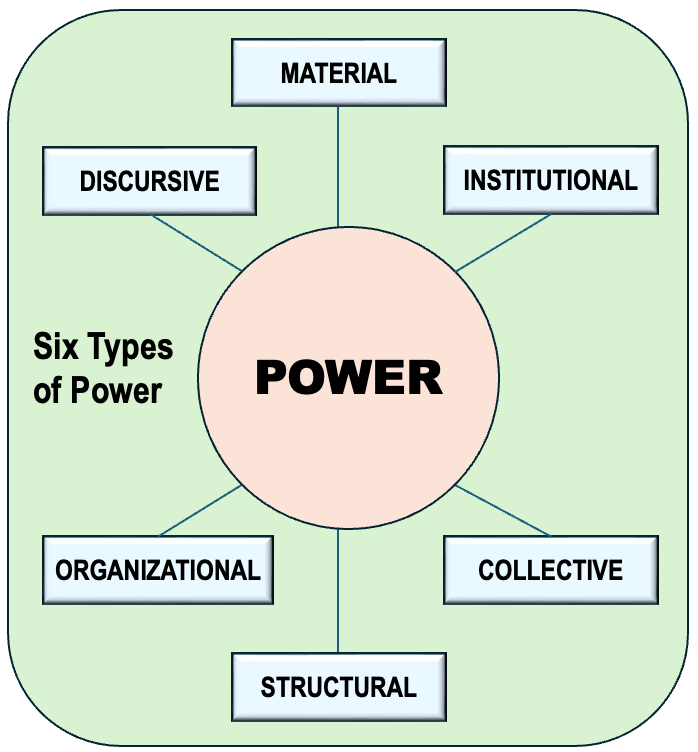

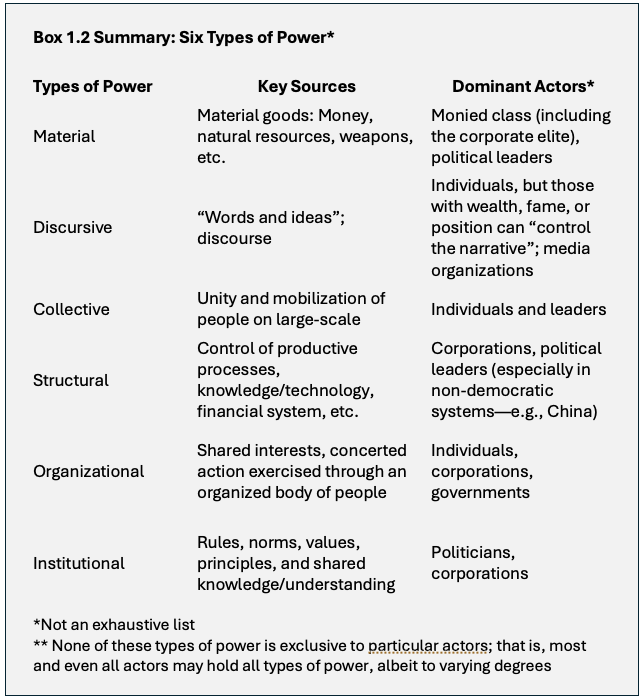

Thus, when thinking about power, it’s crucial to keep two general points in mind. First, power is multidimensional. This simply means that there are different kinds and different sources of power. (See Box 1.2 for summary of the various types and sources of power.) These types and sources of power typically overlap and can often be mutually reinforcing or mutually constitutive. Several types and sources of power have already been directly mentioned: Material, discursive, and collective. Another type of power was alluded to, namely, organizational power. Organizational power overlaps with collective power but differs in that it involves a higher degree of planned (or organized) and sustained cooperation, typically through an identifiable body. It is reasonable, in this regard, to consider a single business or corporation as an organization. And, indeed, a single corporation acting alone may be a powerful organizational force, but a large number of corporations acting in concert or as a single entity will, generally speaking, be more powerful.

Not surprisingly, there are numerous business organizations, including the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Realtors, the Business Roundtable, and many others, which pool their resources and coordinate their interests in order to influence legislators and policy directly or indirectly. There are also powerful non-business organizations such as the National Rifle Association (NRA), which is an organization for gun enthusiasts and gun rights advocates (it has somewhere between three and five million members). The NRA also happens to be one of the most powerful lobbying organizations in the United States. While it’s true that the NRA is a well-funded organization—in 2018, the NRA and its affiliates brought in about $412 million while spending $423 (Leonnig, Zezima, and Hamburger 2019)–but it annual funding pales in comparison to the largest corporations, which have annual revenue in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Beyond wealth and organizational capacity, corporations (or the people who control them) have another key source of power since they largely manage or control the systems of production, finance, and knowledge-intensive technology. This is what scholars refer to as structural power. Those with structural power have power in virtue of the key and often indispensable positions they occupy in the economy as a whole. Here’s how one set of scholars describe the structural power of corporations:

They control most of the crucial resources on which society depends, including investment capital (and thus jobs and loans) as well as food, transportation, medicine, health care services, and countless other things. The investment decisions made in corporate boardrooms help determine employment levels, the location of jobs, the availability of loans, the price of critical goods, and the revenues available to government (Young, Banerjee, and Schwartz 2020)

In sum, corporations control and sometimes dominate the things that everyone needs and wants; as a result, they are always going to have a lot of say—but not necessarily complete say—in how resources are allocated, distributed, and used within any society, especially in market-based ones. Of course, this control makes it possible for those with structural power to further enrich themselves, while those with wealth can use their vast funds to gain structural power. This latter point, it is worth highlighting, is a basic example of how difference sources and types of power are mutually reinforcing and mutually constitutive.

Institutional Power

At the risk of overdoing this discussion, there is one more aspect of power that needs to be highlighted: Institutional power. “Institutional,” in this context, does not refer to organizations or concrete entities (e.g., a financial institution, business organization, or the Congress); rather it refers to rules (both written and unwritten), norms, values, principles, and shared knowledge and understanding by members of society on the way things are supposed to be done. Institutions, moreover, inform, shape, enable, and constrain individual and collective behavior; crucially, they are most relevant and strongest when the vast majority of people within a society, and even across multiple societies, not only accept institutional rules, norms, etc. but also put them into practice or action in a routine manner, often to the extent that they have been thoroughly naturalized or simply taken for granted.

Box 1.3 Key Concepts: Democracy

Democracy is a contentious term. Scholars, in particular, have spent a lot of time debating its meaning. For the purposes of this book, however, democracy will be defined in a straightforward and analytical manner. Accordingly, here are four things that are required for democracy:

- Universal or near universal and equal suffrage.

- Free and non-corrupt elections, held on a regular basis.

- An effective legal framework of civil liberties and rights.

- A competitive multiparty system (meaning that there is more than one political party and that all parties have a fair opportunity to win an election).

To repeat: Not everyone would agree with the foregoing definition for a democracy, in part because it doesn’t seem to say anything about the quality of democracy, or perhaps because it is based on either-or criteria when, in the real world, the political picture is usually grey and fluid. All of this is true, but it is important to emphasize that the criteria or components are not meant to reflect a perfect or ideal democracy, nor are they meant to imply that democracy is a black-and-white, static condition.

Instead, they are meant to be the minimal criteria that must be met for a political system to qualify as a democracy. If one or more of the (analytical) criteria are not fulfilled, in other words, then we can say that the system is not democratic, although it may be partly democratic. For people who study democracy, being able to distinguish between democratic and non-democratic political systems is essential but most also believe that there are qualitative or meaningful differences between regimes that don’t fulfill the four criteria and those that do. The former are typically some form of autocratic or authoritarian system (e.g., a dictatorship) or a hybrid regime—i.e., a regime that are neither fully authoritarian nor democratic.

Most readers are already familiar with key institutions in American politics (as defined here—see Box 1.3 Key Concepts: Democracy). The most familiar is democracy itself. Understandably, it might be hard to see democracy as an institution. Yet, it is not difficult to understand that, when it comes right down to it, democracy is essentially a set of norms, values, principles, and shared understanding of how to organize and operate a political system. Democracy, it is also important to emphasize, is an overarching institution, meaning that there is a subset of institutions tightly connected to it. In the case of American democracy, this means holding regular elections for a range of positions, wherein majority voting applies most of the time, although it does not apply when electing the president. In American democracy, moreover, the loser of an election is expected to voluntarily, and even graciously, relinquish office (this is an example of a norm).

Significant elements of American democracy, of course, are codified as part of a written constitution. The US Constitution and its amendments specifies a range of things, including how the Constitution itself can be changed and how its various parts can be authoritatively interpreted, i.e., through the judiciary and, ultimately, by “one Supreme Court” (Article III, Sec. 1). The Constitution also lays out the basic organizational structure of the federal government and provides some details on the functions, roles, responsibilities, and privileges of each part. While this may seem concrete, remember that the US Constitution is literally just “words (and ideas) on paper.” Thus, powerful as they may be, democracy, the US Constitution, and other institutions of American politics, such as the rule of law, do not themselves have power.

At the same time, institutions can and do have powerful effects, both in terms of who has power (or who has the capacity to get their way) and in how resources are organized, allocated, distributed, and used within any society. As a source of institutional power, the US Constitution, to follow through on the foregoing discussion, gives elected officials—such as congressional representatives, senators, Supreme Court justices and other federal judges, and the president—specific powers in virtue of the institutional positions they occupy. More concretely, and fairly obviously, Barack Obama and Donald Trump had or have far different and greater powers as presidents than they do as presidents. As presidents, they were enabled to do a range of things that no other individuals in the United States (or even globally) were able or authorized to do; however, they were also constrained by rules and, to a lesser extent, by agreed upon norms of presidential behavior. (It is important to emphasize, however, that abiding by “agreed upon norms” is essentially voluntary.

As Donald Trump has demonstrated and is demonstrating even more strongly in his second term, violating norms is clearly possible, especially if other branches of government are similarly willing to go along with and even support violations.) In a similar vein, the NRA has power not just because it is a cohesive organizational force with significant financial resources, but also—and perhaps more importantly—because of what is written in the Second Amendment to the Constitution: “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” This seemingly simple phrase—which is also subject to authoritative interpretation by the Supreme Court (thereby giving the Court’s individual justices profoundly significant institutional power)—has provided the NRA tremendous capacity to get its way, a capacity it almost certainly would not have with its organizational and material power alone.

The institutional power the NRA enjoys today, as was just alluded to, has not always been as strong. This is because the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment, until fairly recently, avoided drawing a firm line on the question, “How far does the right to bear arms extend?” This question was answered, in large part, in a 2008 decision (District of Columbia V. Heller), which held that the Amendment “protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia, and to use that arm for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home” (cited in Legal Information institute 2008). Consider how much weaker the NRA would be if the Supreme Court had ruled that the right to own a firearm had to be connected to service in a militia. This example, though, while important in its own right, underscores the key point of this discussion, namely, that institutions and institutional power, are not static or fixed. That is, they can and do change, especially over long stretches of time. This is largely because they are not independent from the societies in which they’re embedded. Simply put, people made and sustain institutions and people can unmake or remake, redefine, or reshape them.

Many observers believe, for example, that democracy in the US—and in other parts of the world—has been under threat precisely because a large number of people, including prominent politicians and a former president (and tens of millions of ordinary citizens), no longer want to abide by its basic rules and norms. If enough people and, especially, the “right” people no longer agree with its core institutional principles and refuse to abide by them, democracy will simply crumble—from a comparative perspective, we know this is a very real possibility, especially recently as “democratic backsliding [has become] … an overwhelming fact of contemporary global politics” (Carothers and Press 2022, 3). From a less extreme and broader historical perspective, as an institution, “democracy” in America looks very different today than it a few centuries ago when another core institution—slavery—was a dominant part of the American social, political, and economic landscape.

Slavery: Bringing Us Back to the Importance of Race

The reference to slavery is not coincidental since it provides a nice segue back to race/racism and also to class, as the institution of slavery reflected a specific type of race-based (or racialized) class hierarchy in the United States. To most Americans, slavery seems like ancient history. But while the physical manifestations and practices of chattel slavery disappeared in the US, there is little doubt that racism—a core element of slavery—continued to permeate all aspects of American politics, economy, and society: From electoral politics and voting rights, to education, public health, housing, transportation, travel, employment, recreation, marriage, immigration, etc. Put simply, race/racism remained an integral and unavoidable part of the American landscape and of American politics long after the end of slavery. Of course, there has been a lot of intense public debate on how important race/racism (and white supremacy) has been and continues to be now in the 21st century. Consider this quote from an opinion article published in 2023 in the (conservative) Washington Times:

Democrats and their cries of racism: It’s like listening to those yappy dogs that just won’t quit, even after you’ve passed their yards — even after you’ve turned the corner — even after you’ve disappeared from view and gone on with life. Yap, yap, yap — racism, racism, racism (Chumley 2023).

The argument in the foregoing passage, to be clear, is that racism is no longer real or relevant, except to those who wish to play the “victim card.” It’s not possible to convince those who hold this view that they’re wrong (but they certainly are); suffice it to say, then, that the long history of racism and race-based politics is plainly visible and clearly demonstrable, including today. But the more important point is that race/racism doesn’t have to be “in plain sight” (although it still very much is) to be relevant and powerful. To understand why, it’s important to take a deeper and more explicitly theoretical dive into the significance of race/racism, which necessarily includes its tightly woven connection with class, in American politics.

Basic Framework of Analysis: Theorizing Class/Race and Power

Many university professors, especially in the social sciences, tend to emphasize theory and theorizing. Most students, on the other hand, find (academic) theory either pointless or, well, “academic,” meaning that it’s too abstract or esoteric to be of any help in making sense of the real world. Admittedly, student perceptions are not entirely off base. However, good academic theories are important and even necessary in that they provide a path toward deeper and stronger understanding of the world in which we all live.

Good theory is also explanatory. That is, it allows us to identify and makes sense of the most significant factors and forces that lead to or are responsible for the real-world outcomes we see around us, such as high or low rates of economic inequality, poverty, crime and societal violence, incarceration, to name just a few relevant possibilities. Theory, moreover, doesn’t have to be complicated or difficult to understand. Perhaps without realizing it, you have already been introduced to theory/theorizing in this chapter: The foregoing examination of the six different types and sources of power was, at base, an exercise in theorizing power; it is the “theory of power” upon which the argument in this book is based. Assuming you followed that discussion without too much or any difficulty, you have already absorbed the first main theoretical lesson in theorizing class/race and power.

A Few Preliminary Points

Before specifically theorizing class/race, it might be helpful to say a few words about what a “theoretical framework of analysis” is in general. In the most basic terms, a theoretical framework of analysis, or analytical framework, in the social sciences is a (conceptual) tool that allows us to develop logically consistent but also manageable explanations for a range of political, social, or economic outcomes. Importantly, it does this, in part, by connecting core theoretical principles and assumptions to real world facts is a coherent manner. Keep in mind that one of the difficulties in deciphering how and why things work or end up the way they do in our world is figuring out what facts are relevant to an explanation and what facts are not. Another difficulty is having a consistent way of determining how to properly interpret facts. An analytical framework helps to address both these problems by: (1) leading us to focus on some facts over others; (2) giving us a method of demonstrating how and why those facts are significant; (3) helping us organize the relevant facts; and (4) enabling us to develop whole arguments, that is, arguments that stick together firmly from beginning to end.

In the social sciences, there are multiple and usually competing analytical frameworks, each of which is based on a number of different principles and assumptions. In this regard, the analytical framework used in this book—which adopts a non-mainstream approach, especially for textbooks covering American politics—is not meant to be the last word. Far from it. Instead, it’s meant to give most students one alternative, unconventional way of thinking about and examining American politics. Thinking beyond the mainstream, I should add, is an essential element of critical thinking. After all, if you never consider alternatives modes of thought or explanation, it’s difficult to engage in careful, well-reasoned, and reflective evaluation—which is one general way of defining critical thinking.

Critical thinking, moreover, also means “relying on reason rather than emotion; being precise; considering a variety of possible viewpoints and explanations; weighing the effects of motives and biases … not rejecting unpopular views of out hand; being aware of one’s own prejudices and biases; and not allowing them to sway one’s judgement” (emphasis added; Kurland 1995). An overarching goal of this book is to encourage critical thinking. Thus, even if you find yourself disagreeing with some or most of the analysis that follows, as long as you take it seriously by carefully considering the basis for your disagreement and thinking about the evidence (or facts) that supports your position, you will still have gained a lot. Conversely, even if you agree wholeheartedly, you should maintain a healthy degree of skepticism about the arguments made in the pages that follow by seriously considering alternative explanations and views. Ultimately, though, a good critical thinker will “take a stand” or develop a position of their own, which they can support both empirically (that is, with evidence) in an intellectually honest manner.

The Class-Race-Power (CRP) Framework

The analytical framework in this book, as is already quite clear, emphasizes the intersection of class/race and power. I’ve already discussed the meaning of these three terms; that was an important first step. The next step is to explain how each “operates” and how and why they interact a create a particular pattern of political outcomes in the United States. On this last point, it is important to repeat and to clarify that this framework is not meant to explain the persistence of racial disparities, inequities, and discrimination in the United States, which are undoubtedly important. Rather, the intent is to use an CRP framework at broader level, to answer the sorts of questions posed at the beginning of this chapter. This said, the significance of class and race has been subject to a great deal of analysis for many decades. And, while disagreements remain (scholars in the social sciences rarely reach complete consensus on any significant theoretical issue), at least among those take both factors seriously, there is basic agreement that class and race are both powerful forces in their own right and, more importantly, are inextricably connected in a way that has helped make the United States “special” compared to other wealthy democracies.

Before discussing the significance of the connection between class and race, it would be helpful to identify (or reiterate) three key assumptions in the CRP framework. The first is the most basic and has already been discussed: In all modern, market-based, or capitalist, societies there is an unavoidable and important division between those who work for a living (the working and middle classes–which will be collectively referred to as the wage earning class in this book–as well as the upper income class) and those who own or control the companies that produce goods and services (the corporate class). Market-based economies, to repeat another basic point, also produce an upper income class (say, the top 1% with incomes of around $500,000 a year) and a much wealthier class, the monied class, who take home a minimum of $35 million a year (figure is for 2018, representing the top 0.01%; Picchi 2018).

Members of the monied class include the corporate elite, but also include (as I noted earlier) entertainers, media personalities, actors, professional athletes, heirs to large fortunes, even lottery winners and others with massive incomes and wealth. The monied class has tremendous material power, but except for those who also control corporations, they generally do not have significant structural power. Moreover, the core interests of much of the monied class are disparate and often do not correspond with the core interests of the corporate class. Thus, while the monied class may largely align on some public policy issues (such as taxes), there may not be much alignment on others (e.g., corporate regulations or policies related to climate change, health care, education, labor standards, unemployment, and so on). The issue of class interests, a second key assumption, is essential to highlight as the CRP framework presumes that the core interests of the corporate class are different from the core interests of the other classes, and that this difference has a major impact on the political process. I will provide a more detailed discussion of this last point, which includes providing real-world support, in Chapter 5.

Third, in all democratic market-based societies, the corporate class has significant and generally predominant power in two closely related categories: material and structural (in non-democratic countries, state leaders will typically have dominant material and structural power). In addition, the corporate class typically exercises significant but not necessarily dominant power in three other categories, discursive, organizational, and institutional. In a democracy, though, corporate power can be “checked” or counterbalanced by other actors and social classes exercising discursive, collective, organizational, and/or institutional power.

Whether or not corporate class power is effectively counterbalanced depends on a range of considerations, some of the most important of which have deep historical and institutional roots. According to the CRP framework, when corporate class power is not effectively checked, the results are clear: A political system that revolves around the protection, promotion, and reinforcement of the interests of the corporate class. When corporate class power is effectively counterbalanced, by contrast, the interests of the corporate class may still prevail in some areas, but in other areas, corporate class interests may take a back seat to the interests of other actors and groups in society.

So, what is the is the significance of the connection between class and race/racism in the United States? To grasp a basic element of this connection, it would be useful to engage in a bit of counterfactual or “what-if” thinking. Accordingly, think about how politics in the United States would differ if, with class relations fully intact, race/racism were not a major factor. (I hope you think a little about this question before reading on.) First consider what would not be different.

On the one hand, for example, we can be confident that there would still be political divisions, whether between liberals and conservatives or some other partisan division. We know this by looking at homogenous or largely mono-ethnic democracies such as Japan, South Korea, and Iceland, all of which have multiple political parties with opposing ideological positions.[3] For the same reason, we can surmise that religious beliefs and organized religion would continue to play an important role in American politics and that gender-based discrimination (e.g., the gender pay gap) would remain. We can also surmise that the corporate class would still be a major political actor with a great deal of power; again, we can see this by looking around the world: The corporate class is a significant political actor in all market-based democracies (from now on, I will only say “democracies,” since all democracies in the world have market-based or capitalist economies). In addition, and perhaps most importantly, the basic division between those who work for a living and the monied and corporate classes would be largely unchanged.

On the other hand, without race/racism playing a role in American politics, it is very likely that class relations in the United States would play out quite differently. As many scholars using a class analytic framework argue, aside from blatant racial discrimination, one of the most obvious effects of race/racism is its role in dividing the lower income or working class along racial lines (for example, see Wood 2002) Thus, without race/racism, this class would be a more unified and coherent force, giving it great collective and organizational power, as well as more discursive power; combined, this would lead to a stronger institutional position and thus great institutional power. At a more practical level, this would mean stronger protection of worker rights and, ultimately, a stronger political voice for those who work for living. Fairly clearly, too, poverty and incarceration rates would be far lower, and there would be less discrimination in housing, policing and the justice system, health care, employment, education, travel, access to banking and other financial services, and so on. To be sure, there would still be societal inequity—which generally refers to injustice, bias, unfairness, and inequality—but it would obviously not be based on race/racism and instead would be primarily class-based. Less clearly, with race/racism, it is likely that how the US interacts with the rest of the world would be different. This will be discussed in Chapter 6.

The core theoretical point is this: Race/racism profoundly alters the dynamics of class relations in democratic countries. This statement, it is worth noting, presupposes that class relations, in essence, go before race/racism. Such is the case. As Ellen Meiksins Wood asserts, “ … class is constitutive of capitalism in a way that race is not. Capitalism is conceivable without racial divisions, but not, by definition without class” (Wood 2002, 276). This is easy enough to see by adopting a comparative perspective. To wit, in market-based or capitalist societies around the world, the same basic class divisions repeat themselves over and over, regardless of the history of or level of racism.

Saying this, however, does not mean that race/racism is somehow less important or less significant. That is not the case. In the context of American history, in particular, race/racism has played an instrumental role in skewing class power, by racializing class divisions. Race/racism, to put this issue in different terms, has created an “extra-economic” class hierarchy (Wood 2002) that has directly led to, or caused, the deep societal inequities discussed earlier in this chapter. This racialized class hierarchy is deeply embedded in the American system such that it has become almost impossible, in practical terms, to disentangle class from race. The upshot is that the “inextricable connection” between class and race in the United States has enabled the corporate class not merely to exercise outsized control of the political process (which, to repeat, happens in all democracies to varying degrees), but also, in important respects, to dominate the process in those areas where corporate class interests are strongest. Corporate domination of the political process, in turn, has, to put it baldly, made American democracy less democratic for everyone living in the United States, but especially for Black Americans.

I should also re-emphasize that race/racism, while strongly associated with the rise of market-based or capitalist economies, also has independent effects apart from class dynamics, whether in the US or elsewhere. Similarly, as should already be apparent, class relations and dynamics are not always associated with race/racism. In short, there are times when race and class should be analyzed as more-or-less separate from each other or as essentially independent forces, which this book will do when appropriate.

The Plan for the Rest of the Book

The following chapter will examine American politics from a basic comparative perspective. Part of this “basic” comparative analysis will mostly focus on the differences between United States and a number of “peer democracies.” The general purpose is to demonstrate an obvious, but still important point, namely, not all democracies are alike. This is an important point because it demonstrates that the policies and laws that exist in the United States—ones that heavily favor the corporate class—are not necessarily inevitable. That is, the corporate class, while powerful in all market-based or capitalist countries, is not always all-powerful; it is possible for the wage-earning class to exercise greater political power, to get more of what it wants.

Chapter 3 delves more deeply into the basis of corporate class power in the United States. This not only entails a bit of historical analysis, but also a careful look at how the corporate class has established an organizational network that allows it to more effectively exercise its power in the American political system. Chapter 4 considers the notion of “American exceptionalism,” which is often portrayed as defining feature of American greatness. However, as we’ll see, American exceptionalism has a great deal to do with the role race has played in American society and politics since the country’s inception. The chapter argues that a big part of what makes America exceptional is the manner in which race and class have become integrally entwined.

Chapter 6 considers how democracy in the United States has been profoundly reshaped such that “the average citizens’ influence on policy making is essentially zero.” The chapter first examine core elements of American politics: The electoral and party systems; the role of mainstream media and social media; and the legal-constitutional system. It will then focus on three key policy issues, in which corporate class power is particularly salient. These three issue areas are tax policy for the corporate class, corporate welfare, and climate change policy.

While Chapter 6 looks at domestic policy issues, Chapter 7 shifts the focus to foreign policy. “Foreign policy” refers a range of policies that relate to how the United States interacts with other countries; these can range from trade relations to war. Again, given the sheer breath of foreign policies, this chapter revolves around a manageable set of selected issues. Chapter 8 shifts our focus once again. Instead of considering American politics at the national level, this chapter considers politics within two states, one “Blue” (California) and one “Red” (Texas). This is a different type of comparative analysis but one that can be very instructive. At the most basic level, it demonstrates how, even with the US, there can be significant, even profoundly significant, differences in the policies that elected representatives pursue. Less obviously, it shows how, in different contexts, corporate power is either maximized or limited. Chapter 9 is the concluding chapter. This final chapter will consider the future of American politics, as the country has not only become more polarized but also dangerously close to abandoning the principles of democratic governance altogether.

Chapter 1 Notes

[1] The OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) is an international organization, which established in 1960 and was originally limited to western European countries, the US and Canada. Over the years, the membership expanded to 37 countries, including almost all of the world’s wealthiest countries.

[2] Wealth and income are often used synonymously, but they are not the same. Income is what a person earns from wages and/or investments, usually expressed on an annual basis. Wealth is value of accumulated assets (savings, investments, home equity and other property, etc.) less any debt.

[3] Scholars have described these three countries, along with North Korea, as the most “historically” homogeneous countries in the world (see, for example, Kymlicka 2007), which is highly debatable (Lim 2021). But there is much less argument about efforts by a range of countries, but especially Western ones, to actively construct a homogeneous society. In other words, homogeneity is another social construction.

Chapter 1 References

AustralianPolitics.com. n.d. “Liberal Democracy.” AustralianPolitics.com. https://australianpolitics.com/democracy/key-terms/liberal-democracy

Brabec, Martin. 2019. “Interconnection of Class and Race with Capitalism.” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 18:36-46

Carothers, Thomas, and Benjamin Press. 2022. Understanding and Responding to Global Democratic Backsliding. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Chumley, Cheryl K. 2023. “Barack Obama Falls Flat with His Tired Race Card Toss.” Washington Times, June 16. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2023/jun/16/barack-obama-falls-flat-with-his-tired-race-card-t/

Cunningham, Danny. 2022. “Lebron James, the Businessman: 5 Companies Owned by the King.” Basketball News, June 7. https://www.basketballnews.com/stories/nba-lebron-james-the-businessman-fenway-sports-group-springhill-entertainment-uninterrupted-blaze-pizza-ladder-athletes-companies.

Dyer, Justin Buckley. 2011. American Soul: The Contested Legacy of the Declaration of Independence. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Guerrasio, Jason. 2022. “Tom Cruise Raked in $100 Million for ‘Top Gun: Maverick,’ Making Him the Highest-Paid Actor This Year. Here Are the Other Top Earners in Hollywood.” Insider, July 23. https://www.insider.com/highest-paid-actors-this-year-tom-cruise-dwayne-johnson-2022-7.

InfluenceMap. 2019. How the Oil Majors Have Spent $1bn since Paris on Narrative Capture and Lobbying on Climate. InfluenceMap.https://influencemap.org/report/How-Big-Oil-Continues-to-Oppose-the-Paris-Agreement-38212275958aa21196dae3b76220bddc.

International Labor Organization. 2022. Which Country Has the Highest Trade Union Density Rate? Statistics on Union Membership. https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/union-membership/.

Knight, Brett. 2022. “The World’s 20 Highest Paid Athletes.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brettknight/2022/05/11/the-worlds-10-highest-paid-athletes-2022/.

Kurland, Daniel J. 1995. I Know What It Says—What Does It Mean? Critical Skills for Critical Reading. New York: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Kymlicka, Will. 2007. Multicultural Odysseys: Navigating the New International Politics of Diversity. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

LaFranco, Rob, and Chase Peterson-Withorn. 2023. “World’s Billiionaire List: The Richest in 2023.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/.

Lasswell, Harold D. 1936. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How. New York: Whittlesey House.

Leftwich, Adrian. 2004a. “The Political Approach to Human Behaviour: People, Resources and Power.” In What Is Politics?, edited by Adrian Leftwich, 100-118. Cambridge (UK) and Malden, MA: Polity.

Leftwich, Adrian. 2004b. What Is Politics? : The Activity and Its Study. Oxford: Polity.

Legal Information institute. 2008. Syllabus: District of Columbia V. Heller (No. 07-290). Cornell: Cornell Law School.https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/07-290.ZS.html.

Leonnig, Carol D., Katie Zezima, and Tom Hamburger. 2019. “Inside the Nra’s Finances: Deepening Debt, Increased Spending on Legal Fees — and Cuts to Gun Training.” Washington Post, June 14. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/inside-the-nras-finances-deepening-debt-increased-spending-on-legal-fees–and-cuts-to-gun-training/2019/06/14/ac9dc488-8e30-11e9-b08e-cfd89bd36d4e_story.html

Lim, Timothy C. 2021. The Road to Multiculturalism in South Korea Ideas, Discourse, and Institutional Change in a Homogenous Nation-State. London and New York: Routledge.

Logan, John. 2009. “Union Recognition and Collective Bargaining: How Does the United States Compare with Other Democracies?” UC Berkeley Labor Center. https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/union-recognition-and-collective-bargaining-how-does-the-united-states-compare-with-other-democracies/.

Nittle, Nadra Kareem. 2017. “Notable Quotes from Five of Martin Luther King’s Speeches ” ThoughtCo, May 13. https://www.thoughtco.com/notable-quotes-martin-luther-kings-speeches-2834937.

OECD. 2015. In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Pew Research Center. 2020. What Census Calls Us. Accessed February 6, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/interactives/what-census-calls-us/.

Picchi, Aimee. 2018. “How Much Do the 1, .01 And .001 Percent Really Earn?” CBS News, February 27. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/how-much-do-the-1-01-and-001-percent-really-earn/.

Reed, Adolph, Jr. 2013. “Marx, Race, and Neoliberalism.” The Marxist Moment 22 (1):49-57

Tyson, Alec, Cary Funk, and Brian Kennedy. 2023. What the Data Says About Americans’ Views of Climate Change. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/18/for-earth-day-key-facts-about-americans-views-of-climate-change-and-renewable-energy/.

Wiadra, Emily, and Tiana Herring. 2021. “States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021.” Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2021.html.

Wood, Ellen Meiksins. 2002. “Class, Race, and Capitalism.” Political Power and Social Theory 15:275-284

Young, Kevin A., Tarun Banerjee, and Michael Schwartz. 2020. “The Secret to Corporate Power.” Yes!, July 13. https://www.yesmagazine.org/democracy/2020/07/13/corporate-power-politics.