8 Blue and Red States: A Comparative Examination of California and Texas

Introduction: “Laboratories of Democracy”

The notion that states are laboratories of democracy is generally attributed to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandies, although he didn’t use those exact words. In his dissent in New State Ice Co. v. Liebman, Brandies wrote, “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country” (emphasis added; New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann 1932).

Brandies’ use of the terms “laboratory” and “experiment” were purposeful: He wanted to emphasize that, like laboratories, individual states could and should experiment with different policies and approaches to governance, to see what the consequences—both for good and bad—would be in the real world. At the same time, of course, states aren’t actual laboratories, and the on-the-ground reality of individual states is too “messy” and complicated to conduct valid experiments—this is because experimentation (based on the scientific method) requires a carefully controlled environment in which different and specific variables can be either introduced or eliminated and then adjusted to test their effects. Still, the idea of learning from the experiences of different states is a very useful one. This is especially the case if we dispense with the notion of experimentation (or the scientific method) and, instead, adopt another method, namely, comparative analysis.

In this chapter, I will primarily compare California and Texas, which are, respectively, quintessential representatives of Blue States (i.e., liberal or progressive and dominated by Democrats) and Red States (i.e., conservative and dominated by Republicans). My intent in comparing, however, is decidedly not to demonstrate that one state is better than or preferable to the other, although you may draw your own conclusions. Rather, in conjunction with the comparison of the United States with peer democracies in Chapter 2, my intent is to use the comparison to identify and then examine the key factors that led to significant differences in public policy between the two states; at the same time, the comparison will highlight key similarities. Comparing individual states, unlike comparing peer democracies, has several advantages.

First and foremost, all states are, of course, part of the United States. This means that they are bound or constrained by the same Constitution and are subject to the authority of the federal government when it comes to federal laws and regulations. With regard to the former, Brandies, in his same dissenting opinion cited above, put it this way: “We [the Supreme Court] may strike down the [state] statute which embodies it on the ground that, in our opinion, the measure is arbitrary, capricious, or unreasonable. We have power to do this, because the due process clause has been held by the Court applicable to matters of substantive law as well as to matters of procedure (New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann 1932). With respect to the latter, the Supremacy Clause (Article VI, Clause 2 in the US Constitution), holds that laws passed by the federal government “shall be the supreme law of the Land,” a principle that has generally been upheld by the Supreme Court (for further discussion, see Legal Information Institute n.d.).

The fact all states are subject to the Constitution and federal laws, from a comparative perspective, allows us to establish a baseline of sorts. In addition, it reasonable to assume that California and Texas (and all other states) are also all subject to the substantially same set of pressures, including lobbying, by the corporate class. This is another important baseline condition. To put the issue more concretely—and perhaps obviously—given the baseline conditions all states are subject to, we know that the policy differences that exists between California and Texas likely originate within the states themselves. In keeping with the theme of this book, I argue that the differences can be explained, albeit not completely, by applying the class-race-power (CRP) framework. To repeat, though, it’s not just differences between California and Texas that matter; the similarities between the two states can also yield important lessons. For, as we’ll see, corporate class power plays an outsized, although not equivalent, role in both states.

This chapter will begin with a brief and basic comparative overview of the two states. The focus will be on their economies, their populations (including overall size and degree of diversity), state and party politics, and voting and party affiliation. The comparative overview will give a good sense of the basic similarities and differences between the two states. The second part of the chapter will examine three policy issues: labor, climate change, and immigration. There are many other issues that could be examined, but these three are particularly relevant for the purposes of this book. Labor and climate change policy will underscore both the power and limits of power of the corporate class, much of which is dependent on the political context (e.g., whether Democrats or Republicans are dominant). Immigration policy is in a slightly different category. Corporate class power is not unimportant, but I chose to focus on immigration policy in California and Texas mostly because it demonstrates the central role that race can and does play in the political process at the state level.

California and Texas: A Brief and Basic Comparative Overview

The Economies

California and Texas are the two largest economies in the United States, which also, it is worth noting, puts both into the top ten largest economies in the world. In 2023, California’s GDP was $3.86 trillion, ranking it fourth in the world, ahead of 4th place Japan and just behind 3rd place Germany (see image). Texas’ GDP that same year was $2.7 trillion, which was about $1.4 trillion less than California. Not coincidentally, both states also host a large number of Fortune 500 companies, i.e., the cream of the corporate class. In 2024, with 57 companies including Apple, Alphabet, Chevron, Meta, Wells Fargo, Disney and Nvidia, California beat out Texas and New York for having the most large companies inside its borders; Texas and New York were tied for second place with 52 companies each (Burleigh 2024).

California’s number one ranking may seem a bit surprising given the state is frequently criticized for not being business-friendly, a charge that has been amplified by the well-publicized decision by Tesla, led by Elon Musk, to move its headquarters out of California and relocate in Texas—the move was ultimately approved in June 2024 (Morris 2024). Yet, because California has remained a center of the so-called New Economy—which revolves around information technology, the Internet, and other cutting-edge high tech sectors (Keaton 2021)—the state’s supply of large firms has remained high due to the very high growth rates of many relatively new tech-based firms. In addition to some of the companies just listed, these newer, tech-based Fortune 500 firms also include Uber Technologies, Netflix, PayPal, Block, Airbnb, and DoorDash.

Texas also has its fair share of New Economy firms, although the biggest and most prominent are long-established ones, including AT&T, Dell Technologies, and Hewlett Packard Enterprises. Significantly, the largest companies in Texas are energy-based, oil and gas companies. These include Exxon Mobil, the largest company in Texas and the 7th largest on the Fortune 500 list, followed by Phillips 66 (26th) and Valero Energy (29th). Further down the list, but still large-scale energy companies are ConocoPhillips (68th) and Occidental Petroleum (149th) (Fortune Magazine 2024).

While the math is a bit complicated, it is reasonable to say that the Texas oil and gas industry accounts for more than one-third or 35% of the state’s GDP (Mulder 2020). At the same time, Texas has also become the nation’s leader in new renewable energy: wind, solar, and battery storage. On this front, it beats California by a wide margin. In 2021, the Lone Star state had 7,352 megawatts of new wind, solar, and energy storage projects, compared to 2,697 megawatts. As one writer put it, “Texas can claim, with ample evidence, to be the renewable energy capital of the United States. This is despite also being the fossil fuel capital of the United States, and having political leaders who go out of their way to defer to oil and gas” (statistics and quote from Gearino 2022).

The Populations

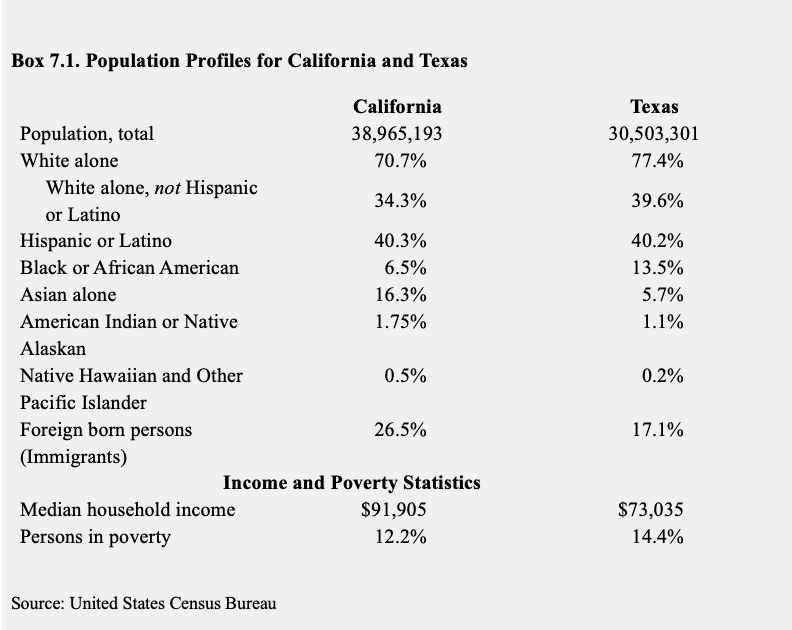

With almost 39 million people in California and 30.5 million in Texas, the two states also have the largest populations in the United States. The composition of their populations, however, differ. In California 70.4% identify as “White alone,” while in Texas the figure is 76.8%. Black or African Americans make up 13.4% of Texas’ population, which in more than twice as high as California at 6.5%. The figures are largely reversed for Asian Americans; in California, Asians compose 16.3% of the population, while in Texas the Asian American population is almost three times lower at 5.7%. The largest racial/ethnic minority group in both states, however, is the Hispanic or Latino population (which includes individuals who identify as “white alone”). Interestingly, the figure is almost identical in the two states: 40.3% in California and 40.2% in Texas (all figures cited in United States Census Bureau 2024a).

California, it is also worth noting, has a significant foreign-born population, with more than one-quarter or 26.5% of residents being born outside the US; that is, a large segment of California’s is composed of first generation immigrants, of whom the vast majority are either legal residents or naturalized US citizens (Mejia, Perez, and Johnson 2024). In Texas the foreign born figure is 17.2%, which is equivalent to about 5.1 million people. Of that number, approximately 1.6 million (32%) are unauthorized, although most of lived in Texas or other parts of the US for 10 years and longer (Migration Policy Institute 2022).

Despite California’s larger population, the state has been experiencing a net outflow of people; that is, more people are leaving the state than entering and settling in the state (although in 2023, California’s population increased by 67,000 people, interrupting three consecutive years of decline [United States Census Bureau 2024b]). The situation has been just the opposite for Texas, as it is one of the fastest growing states in the country. This might indicate that people are “voting with their feet.” That is, the different population trajectories for the two states suggests that, at the individual level, people prefer what Texas has to offer over what California has. At the same time, the net outflow from California could just reflect the very high cost of living in already overcrowded state, which recently singled out as the only US state with more than one “impossibly unaffordable” cities—of 11 cities on an international list, four are in California: San Jose, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego (Ma 2024).

The preceding paragraph underscores another important population statistic, which is unauthorized immigration to the United States. As of 2022, the US Department of Homeland Security estimated that there was a total of 10,990,000 unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Of this total, California and Texas had the largest number at 2.6 million and 2.06 million respectively. Florida was in a distant third place at 590,000. Mexico remained as the largest country of origin for unauthorized or undocumented immigrants, although there has been a long-term declining trend–a trend that has been accelerated since the beginning of Trump’s second term. In 2022, the estimated number of unauthorized immigrants from Mexico was 4.8 million, slightly less than half the total population. The next largest source of unauthorized immigrants were from Guatemala (750,000), El Salvador 710,000), and Honduras (560,000). Outside of the Americas, there have also been a large number of unauthorized immigrants from the Philippines (350,000), India (220,000), and China (110,000) (most figures are for 2022 and all come from Baker and Warren 2024).

State and Party Politics

Today (in 2024), Texas is solidly Republican and conservative (i.e., Red) and California is solidly Democratic and liberal (i.e., Blue). However, it hasn’t always been this way. Texas, in particular, witnessed a fundamental transformation: As late as 1971, more than 90% of elected representatives in the Texas Senate and House of Representatives were registered Democrats. Over the next several decades, however, the Democratic grip on political power gradually slipped away. By 1996, Republicans were able to gain a majority of seats in the Texas Senate and then repeat that feat in the Texas House of Representatives in 2002 (statistics from the Legislative Reference Library of Texas; cited in Miller 2020).

With unitary control, Texas Republicans were able to redraw the state’s congressional districts to ensure that Republicans would gain a strong electoral advantage in the US Congress. This control began in 2004, Republicans picked up six seats in the 31-seat state senate. Since then, the Republican Party has maintained control of the Texas legislature; in 2023, Republicans had an 86-64 advantage in the Texas House (57%) and a 19-12 advantage in the Texas Senate (61%) (Legislative Reference Library of Texas 2023). Republicans have also held the governor’s office since 1995, when George W. Bush was elected, followed by Rick Perry (2000-2015) and Greg Abbott, who won his first election in 2014, was reelected in 2018, and elected for a third time in 2022.

Just as Texas has not always been dominated by the Republican Party, California has not always been a bastion of the Democratic Party. However, unlike Texas, which saw long stretches of one-party dominance, most of the latter part of the 20th century in California was characterized by a back-and-forth movement, with neither party able to establish any sustained dominance. This said, the Democratic Party was able, for the most part, to maintain a simple majority (i.e., 50% plus one) in both houses of the California legislature for most of this period.

Importantly, though, until 2010, passing the state budget or raising taxes required a two-thirds or “super-majority” (66.67%). In practical terms, this gave the minority (Republican) party much greater legislative power or leverage than it otherwise would have since very little can be done without a state budget. In 2009, for example, a single Republican state senator, Abel Maldonado (R-Santa Maria) was able to extract a “series of promises” in exchange for his yes vote; two other Republican senators bartered their yes votes for the promise of weakened environmental regulations (Goldberg 2009). The super-majority requirement for passing the budget (but not for imposing new taxes or issue statewide bond measures) was changed to a simple majority in 2010 through California Proposition 25, which amended the state constitution (Ballotpedia n.d.-b)—ironically, amending the state constitution only required a simple majority.[2]

While Democrats were able to keep ostensible control of the legislature for long stretches of time, this wasn’t the case for that state’s highest position, the governor. In fact, Republicans were able to win the governorship on a recurrent basis, beginning with Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1966. Reagan won two terms, after which a Democrat, Jerry Brown also won two terms. Brown was followed by two successive Republican governors, George Deukmejian and Pete Wilson. The Democrats won the seat back in 1998 under Gray Davis, who was reelected but then subsequently recalled. This led to the election of Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2003, who governed until 2011—it should be noted, though, that Schwarzenegger wasn’t a traditional conservative Republican; it’s also fair to say that his celebrity status broadened his electoral appeal.[3] At least for the time being, Schwarzenegger’s victories were the last hurrah for the California Republican Party.

Since he left office, successive Democrats—Jerry Brown and Gavin Newsom—have controlled the governor’s office for 15 straight years and counting (as of 2025). More importantly, perhaps, at the legislative level, the gap between the Republican and Democratic parties has widened, as Democratic lawmakers were able to achieve super-majorities in both houses of the California legislature in 2012—the first time since the 1800s (CBS News Bay Area 2012). The Democratic Party lost its super-majority in the California Senate shortly thereafter, due to two resignations, but regained it in 2018.

Voting and Party Affiliation

A headline from the Texas Tribune reads, “It’s harder to vote in Texas than in any other state” (Ramsey 2020). By contrast, according to the Cost of Voting Index (COVI), California is one of the easier states for voting, ranking 10th on the COVI, while Texas is ranked 50th in the same index (NIU Newsroom 2020). While voting restrictions are typically justified as a way to ensure “election integrity” or to eliminate “voter fraud,” the reality is that restrictions, usually enacted by the party in power, are designed to suppress the vote among those who are most likely to vote for the other rival party. That certainly seems to be the case in Texas, as one Texas-based journalist argues in his detailed article on voter suppression efforts in his state (see Hooks 2020). Not coincidentally, perhaps, Texas generally has a very low voter turnout rate (i.e., the percentage of eligible voters who cast a ballot), one of the lowest in the country. California’s general turnout rate is higher, although not remarkable so; in the 2022 midterm election, for example, California ranked 24th in the country, while Texas was 43rd (Perry et al. 2022).

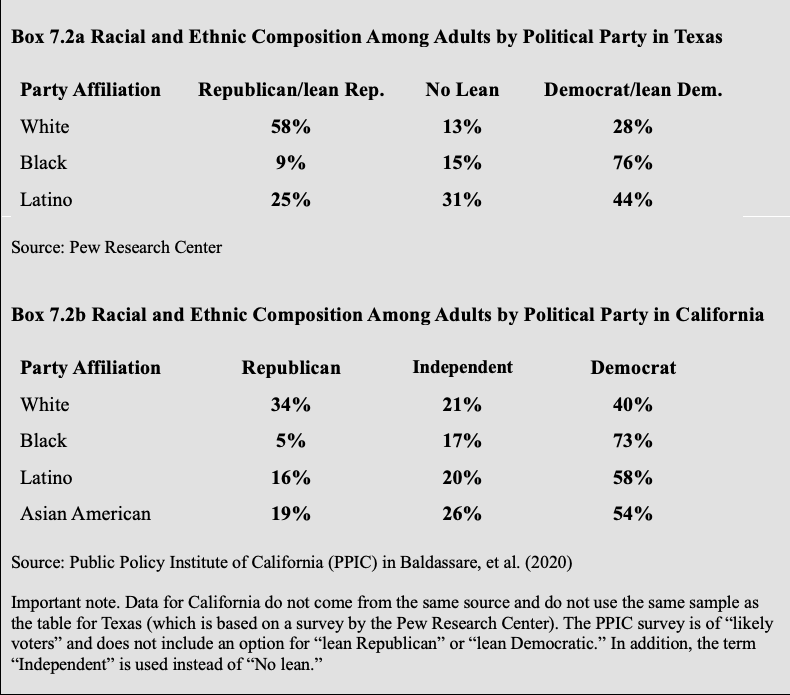

While turnout is obviously important, so is party affiliation among ordinary voters. The foregoing section touched on this issue, but an additional discussion would be useful. This said, there is an interesting contrast between California and Texas. As might be expected, in California, adults who identify themselves as a Democrat, outnumber Republicans, 49% to 30%.[4] Less expected, perhaps, is that there are slightly more adults in Texas who identify as Democrat (40%) than Republican (39%).[5] Breaking these numbers down reveals some interesting information. With respect to party affiliation by race/ethnicity, 58% of white, 25% of Latino, and 9% of Black adults in Texas identify as Republican. In California, the respective numbers are 34%, 16%, and 5%.

These numbers, just to be clear, show a fairly significant difference between the two states, especially for white adults, a point that becomes even clearer when we look at Democratic party affiliation. In Texas, 28% of white, 44% of Latino, and 76% of Black adults identify as Democratic. For California, by contrast, 40% of white, 58% of Latino, and 73% of Black adults identify as Democratic. A key point: In California, the Democratic Party has seemingly been able to transcend—or, at least, blur—racial lines by attracting a plurality or white adults, while also attracting a solid majority of Latino, and Black (as well as Asian American) adults. See Box 7.2a and 7.2b for a summary and additional details.

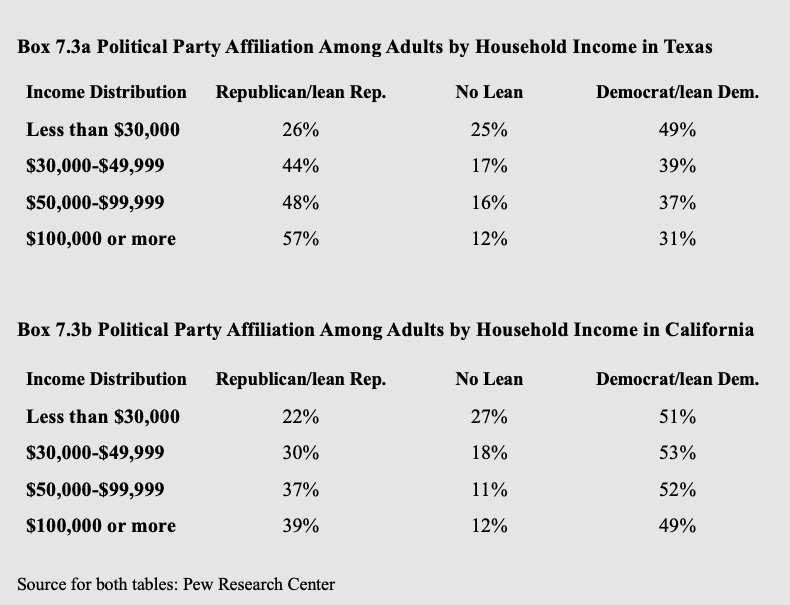

There is one additional and relevant category to look at: Party affiliation by household income. Here, too, the two states also generally differ, although at the lowest income level, less than $30,000 (based on household income), party affiliation is about the same: In Texas, 26% of households earning less than $30,000 a year affiliate with Republicans and 49% with Democrats; in California, the numbers are 22% and 51%. At all other income levels, however, the states diverge. In Texas, for households earning between $30,000 and $100,000, a plurality of adults identify as Republican (or Republican leaning), while in California a majority of adults in the same income category identify as Democrat (or Democrat leaning). See the Box 7.3a and 7.3b for details.

Summary and the Next Step Forward

In the foregoing overview, I purposely did not focus directly on policy issues. The overview, instead, was simply designed to provide the most basic sense of both general similarities and differences between California and Texas. Both states, to repeat, are economic powerhouses and both host major parts of the corporate class. Both states have large, relatively diverse populations with large immigrant communities, legal and unauthorized. Both states also have, overall, more self-identified Democrats than Republicans. Despite this similarity, compared to Texas, California has a much larger percentage of Democrats that Republicans, which, of course, leads to a big difference in the relative strength or political power of the Democratic or Republican parties in the two states. The contrast, over the past decade or so, has become pretty stark with California becoming progressively bluer and Texas become a deeper shade of red.

The blue-red divide, I want to emphasize, provides a very good starting point for the analysis that follows. One reason for this is simple: Since both states have a very powerful corporate sector, it allows us to assess how significantly different political or partisan environments affect the exercise of corporate class power. On this point, keep in that, by and large, all public policy decisions at the state level flow through the state legislature and governor’s office, although California has a very robust direct democracy path whereby citizens are given the power of initiative, referendum, and recall.[6] The initiative is a particular powerful tool, as it allows ordinary citizens to write a proposed law, including an amendment to the state Constitution, which is then subject to approval or denial by a simple majority vote (see Box 7.4 for additional details). Notably, Texas does not provide for citizen-initiated ballot measures.

Box 7.4 Ballot Initiatives in California: A Brief Description

The ballot initiative process gives California citizens a way to propose laws and constitutional amendments without the support of the Governor or the Legislature. A simplified explanation of the initiative process follows.

Steps for an Initiative to become law:

-

Write the text of the proposed law (initiative draft).

-

Submit initiative draft to the Attorney General for official title and summary. *

-

Active Measures are proposed initiatives.

-

Inactive Measures are withdrawn or failed proposals.

-

-

Initiative petitions are circulated to collect enough signatures from registered voters.

-

Signatures are turned into county election officials for verification.

-

Initiative will either be Qualified for Ballot or be failed by the Secretary of State, after verifications and deadline dates.

-

California voters will approve or deny the qualified Ballot Initiative.

Source: Copied verbatim (with minor changes) from the California Attorney General’s website, https://oag.ca.gov/initiatives

In principle, the initiative process is supposed to put political power directly in the hands of regular citizens and voters. In practice, as we’ll see, the issue is more complicated. Importantly, the “complications” will further reinforce a core argument of this book, which is that corporate power is a pervasive and unremitting force in American politics, as well as in democracies around the world. At the same time, while pervasive, its impact is not equally felt. Just as the corporate class has variable political power (i.e., from relatively low to extremely high) in different peer democracies, the corporate class has variable power within the United States. In those states with a stronger Democratic Party—which generally reflects a consolidation of organized labor and wage-earning classes and, equally important, weaker racial divisions (at least when it comes to party affiliation)—corporate class power can be partly and sometimes greatly curbed. In general, in those states with a stronger Republican Party, corporate class power is maximized. Of course, California represents the former and Texas the latter.

Corporate Class Power in California and Texas: An Introduction

It is fair to say that Texas is more “business friendly” state than California. In practice, this means, for example, low corporate tax rates. In fact, Texas does not have a corporate income tax at all, while California has a relatively high (nominal) rate of 8.84%, one of the highest in country. The effective tax rate (the amount actually paid) is much lower, though, at about 4.2% in 2017, which is a result of several corporate tax breaks (Kaplan 2020). (Texas does not have individual income tax, either.) Business friendly also means less protection of workers and especially organized labor or unions, which is generally reflected in the level of unionization. On this point, Texas is one of the least unionized states in the country, which is, to a significant extent, the product of the “right-to-work” campaign, a misnomer that was, fittingly enough, coined by the anti-labor oil industry in Houston as far back as 1936 (Stacker 2021).

Another major domain that reflects a business friendly environment is business-related regulations or legislation. A good example, on this point, is climate change policy. California has adopted numerous climate change mitigation measures over the past several decades and has continued to do so, including, in 2022, the “Advanced Clean Cars II” regularion in August of that year. This rule required that by 2035, every new car and light-duty truck sold in California must either be a zero-emission vehicle (ZEVs) or plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (California Legislature’s Nonpartisan Fiscal and Policy Advisor 2023b). By contrast, according to the Texas Tribune, “Texas legislators largely ignored pleas for critical reform from environmental advocates during this year’s legislative session — failing to act on lowering energy use, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and lessening the disproportionate impact of pollution on communities of color” (Douglas, Foxhall, and Martinez 2023). Note. In June 2025, President Trump signed a congressional resolution that effectively killed the Advanced Clean Cars II regulation.

Two of the areas mentioned above (labor and climate change policy) will be examined in more detail in the remainder of this chapter. Before doing so, however, it’s important to highlight and repeat a key and very basic point, which is this: The level or type of corporate taxes, unionization, or climate change legislation, etc. is always the result of politics or of a political process that involves specific actors or groups exercising power to get what they want (or to get rid of or change what they don’t want).

More specifically, just is a there is organized pressure at the federal level to influence policy (and the legislators who make and enact it), there is organized pressure at the state level. Much, although certainly not all, of this organized pressure comes in the form of lobbying, which—no surprise—is quite significant. In 2023, in a nine-month period between January 1 and September 30, some 4,000 companies, organizations, and local governments spent more than $358 million to lobby the California government. The biggest spenders were Chevron Corp. ($10 million) and the Western States Petroleum Association ($5.3 million). McDonald’s was another major corporate lobbyist, spending about $5 million (all figures cited in Kamal 2023). In Texas, the amount spent on lobbying is similar to California but there is much less transparency.[7] As a result, “the details of … lobbyists’ activities — who they see, how they are entertaining key politicians, and what they talk about behind closed doors — remain largely a mystery” (Transparency USA 2021).

As I discuss below, though, California has a twist, which is the initiative process. This allows any group, including the corporate class, to get propositions put on the ballot to be voted on by the general public. These propositions are sometimes used by the corporate class to challenge laws passed by the legislature, as was the case with Proposition 22 (discussed in detail below). The initiative process requires money (reflecting both material and organizational power), sometimes a great deal of money, but money alone is not always enough to get votes. Keep this in mind as we proceed.

Labor Policy: Union-Friendly California vs. Anti-Union Texas

“Right-to-Work” or “Right-to-be-paid-more”?

One of the best areas to examine when trying to determine the influence of the corporate class is labor policy. The reason is clear: Unions give labor more power to increase wages and improve working conditions, both of which adversely affect the ability of corporations to maximize profits. While broad labor policies are made at the federal level (e.g., the National Labor Relations Act, one provision of which is to give workers the right to form a union), states have a great deal of discretion or room to maneuver. In other words, states can make it far easier for labor to organize and exercise greater economic (and political) power or they can make it much more difficult. Texas has chosen the latter approach, while California has chosen the former.

The difference can be seen in the two states’ approach to “right-to-work” (also referred to as “open shop”) legislation, which I referred to in the previous section. I also mentioned that it is a misnomer. “Right-to-work,” of course, sounds like a good thing. After all, who would object to the right to work? Keep in mind, though, there is, for all intents and purposes, no such thing as a right to work in the United States. Instead, 49 of 50 states allow for “at-will” employment; this means that employers are free to fire an employee for almost any reason, at any time.

Of course, employers also have the right to pick-and-choose the people they hire. This also means there is no right to get work, since you cannot work if you don’t get hired. So, why is the phrased used? The simple answer this: It reflects the exercise of discursive power. The phrase was quite purposefully designed to make ordinary citizens believe the policy is fundamentally about workers’ rights (Miller 2020), about their ability to have a job, rather than, as I explain shortly, hobbling union organizing. It appears to have been a very effective discursive strategy. A 2014 Gallup poll, for example, showed overwhelming support for unions among Democrats (77%), but also, and in a contradictory manner, extremely strong support for right-to-work laws (65%) (Jones 2014).

As I just emphasized, so-called “right-to-work” (RTW) laws are, according to critics, primarily designed to undercut the power of unions since, once a union is certified, it is legally required to represent every employee in a position covered by the union, regardless of whether that employee is a union member or pays union dues. This strongly reduces the incentive for regular workers to join a union, still less pay union dues, as they can “free ride” on any success the union has.[8] (Click here for a discussion of free riding.) The upshot is that unions in RTW states have less bargaining power or less leverage when negotiating with large corporations. Importantly, this has had a concrete impact on how much workers earn in those states. According to a study by the Economic Policy Institute, wages in RTW states are 3.1% lower than in non-RTW states, which translates into $1,558 per year (Gould and Kimball 2015). This is why critics of RTW laws have dubbed them right-to-work-for-less laws. In addition, there may be a racial component to these laws (see Box 7.5 for further discussion).

Box 7.5 RTW Laws and Race: A Brief Discussion

According to Shane Larson, the legislative and political director of Communications Workers of America, RTW “was concocted by a bunch of Southern segregationist white supremacists as an effort to try to stop unions” in the 1930s and 1940s. It was meant to be “a way to keep workplaces from being integrated.”

The policy push, moreover, “was bankrolled by corporations to really whip up this racist hysteria into campaigns to pass these ‘right-to-work’ laws in states all throughout the south.” A leading advocate of RTW laws was a corporate lobbyist from Texas, Vance Muse, who was described by his own grandson as “a white supremacist, an anti-Semite, and a Communist-baiter, a man who beat on labor unions not on behalf of working people, as he said, but because he was paid to do so” (both quotations cited in Constant 2021).

Texas was one of the first states to adopt a right-to-work law (in 1947), so it’s not strictly the product of the more recent Republican dominance in the state. However, it is clear that opponents to right-to-work legislation in Texas have absolutely no chance of overturning it as long as Texas state politics continues to be dominated by the Republican Party. Instead, the Republican dominated legislature in Texas has worked to reinforce it, including passing an updated RTW law in 1993, which barred public employees from engaging in collective bargaining or going on strike. Public employees can still create and join unions, but they are primarily limited to lobbying the legislature every two years. In 2023, to give a more recent sense of their anti-labor rights stance, legislators in Texas—at the behest of corporate lobbyists and conservative think tanks (Miller 2019)—passed a law (i.e., the Texas Regulatory Consistency Act) that banned local governments from requiring (private) employers to provide any sort of employment benefits beyond what the state affords, including paid sick days, advanced notice of scheduling, and mandatory water breaks (Fechter, Douglas, and Nguyen 2023).

In California, by contrast, efforts to pass right-to-work legislation have failed. The last effort was in 2012, although it was not strictly a right-to-work measure; instead, it was designed to prevent unions from using payroll-deducted membership dues to fund state and local candidates. The proposition ostensibly subjected corporations to the same restrictions but, unlike unions, virtually no corporation (a mere 0.01%) relied on payroll deductions to fund politicians. As an initiative, moreover, Proposition 32 was, on the surface, the product of ordinary citizens taking advantage of the state’s commitment to direct democracy. But, as one local newspaper reported, the proposition was the brainchild of “millionaires and billionaires” who also funded the campaign and who also made sure to exempt themselves (and their companies) from the rules of the proposition (The Sun 2012). In this case, the voters were not misled, and Proposition 32 was soundly defeated at the polls by a margin of 56.6% to 43.4%.

Even more, before its definitive “blue turn,” unions had a strong voice in California’s government. In 1974, following his first election, Jerry Brown signed the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (effective 1975), which was a landmark labor law that established the right to collective bargaining for farmworkers. This was the first such law in the United States. Since then, support for unions has generally remained solid, which has helped lead to one of the highest levels of unionization in the country at 16.9% in 2023, more than triple the level of Texas (5.4%). Notably, across the nation, the median weekly earnings of nonunion workers ($1,090) was just 86% of union workers ($1,263) (statistics on both unionization rates and median wages cited in US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2024).

One of the reasons for California’s relatively high unionization level is due to union density in the public sector. More than half (50.7%) of all union members in California work in the public sector (e.g., teachers, fire fighters, professors, and government officials), despite the fact that public sector employees are no longer required to pay “agency fees” due to 2018 US Supreme Court decision (Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees). An agency fee required non-members of a union to contribute to the costs associated with collective bargaining by the union, so banning the agency fee was akin to creating a right-to-work law for public sector unions.

However, to help ensure the vitality of public sector unions, the same day of the Supreme Court decision, California Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 866 into law (“SB” stands for Senate Bill), which prohibits public employers from communicating with their employees about the cost of union membership. Nor are employers allowed to process a request by a worker to leave the union. SB 866, instead, requires the employer to refer the employee to the union itself for any changes in membership (Kunze 2018). Unions also took proactive steps to maintain their membership. As a result, public sector union membership has remained fairly steady since the Supreme Court decision (Artz 2023).

Minimum Wage or Living Wage?

The statewide minimum wage in Texas is $7.25 an hour (equivalent to $15,080 a year based on 40-hour work week), which is the same as the federal minimum wage. The last adjustment was in 2008, when it was increased by $0.70 from $6.55 to $7.25. Even more, the Texas legislature has expressly prohibited local governments from setting a higher minimum wage (Miller 2020). In California, by contrast, the statewide minimum wage is $16.00 per hour, which is equal to a yearly wage of $33,280. Moreover, for California’s roughly 500,000 fast food workers, the minimum wage was increased to $20 per hour beginning in early 2024. Local governments in California are also legally able to set a higher minimum wages and many cities have done so. One of the highest municipal minimum wages is in West Hollywood, which requires a minimum of $19.61 for hotel workers and $19.08 for other, non-fast food workers (as July 1, 2024).

The significant increase in minimum wages in California, to repeat a basic point, did not just happen. The initial effort was heavily pushed by labor unions. As one writer put it, “ … efforts by labor unions to increase the minimum wage … consumed Sacramento.” One of the key union players was the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which “used a ballot initiative threat to compel then-Gov. Jerry Brown into a 2016 deal to phase in a $15 wage over five years,” later increased to $16 due to inflation (emphasis added; White 2024). Equally important, the push to increase the minimum wage to $15 was supported by nearly two-thirds of California’s registered voters, even with the understanding that the increase might hurt their own pocketbooks and the state’s economy (Dillon 2016).

The combination of strong and persistent organized activism and broad public support proved to be a powerful political force. Sometimes, though, this still isn’t enough in the face of concerted corporate resistance but, in a state with a strong labor-liberal alliance, and one which is largely united across racial lines (minimum wage legislation disproportionately benefits “people of color”), it turned out to be enough. Notably, though, the $20 minimum wage for fast food workers reflects a compromise, as McDonald’s along with several business associations and most other fast food companies, led an intense lobbying effort before and after the bill (AB 257 [“AB” stands for Assembly Bill]) was first signed in 2022 (Hussein 2022). To challenge the bill, McDonald’s successfully got a referendum on the 2024 ballot, but agreed to pull it when the original bill was modified, including reducing the minimum wage from $22 to $20 an hour (Kimelman 2024).

Meanwhile, in a state where corporate class power is aided and abetted by Republican-dominated legislature, Texas has become home to the largest number of workers earning less than $15 an hour, roughly 5.7 million workers or 40% of the state’s total workforce (Carter 2022). Democratic members of the Texas legislature have tried to raise the state’s minimum wage, but their attempts haven’t gone anywhere. “Why? It’s controlled by Republicans,” state Sen. Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa said. “Any type of attempt to file legislation in the Texas Legislature to increase minimum wage is dead on arrival. The leadership would oppose it” (quote from Ferman 2021).

Corporate Class Power in a Deep Blue State: Is “The Pen is Mightier than the Sword”?

Even in deep blue California, the corporate class still has ample capacity to influence labor policy. One of the most powerful business organizations in the state is the California Chamber of Commerce (CalChamber). As with any large business association, CalChamber has significant material (and organizational) power: In 2023, it spent $3.45 million on lobbying in an effort to influence more than 150 proposed bills, many of which were focused on labor and employment issues (Kimelman 2024). In addition, CalChamber has adopted a discursive strategy by labeling bills it opposes as “Job Killers.” Every year, it releases its “Job Killer List.” In 2023, the list included nine labor-related bills and 25 proposed bills in all (CalChamber 2023).

The intent behind the term “job killer” is obvious: It is designed to convince regular citizens and voters that the proposed legislation is against their interests, as opposed to being in the interest of the corporate class. Admittedly, it is not clear how effective this discursive strategy is; nonetheless, it is fair to say that it has an effect on state legislators. Writing for Capitol Weekly, Rich Ehisen (2024) put it this way: “Lawmakers have long-dreaded seeing their bills on the list, and for good reason.” The “good reason” is that CalChamber is an effective organization: In 2022, of 19 bills it labeled as job killers, only two were signed into laws. Moreover, as one reporter notes, “Out of the 824 bills that the group labeled ‘job killers’ between 1997 and 2022, only 58 have been signed into law. Translation: Just about 7% of bills the chamber puts on the list make it across the finish line without significant amendments that the business community favors” (Gedye 2023).

Corporate Class Power and Proposition 22

While the significance of CalChamber’s “job killer” list is not entirely clear, it is not difficult to find other cases where discursive power has played a more obvious role. To see this, we need to take a short step back. In the previous section, I noted how fast food corporations, led by McDonald’s, used the initiative process to challenge a bill it did not like. In California, this has been a common strategy used by the corporate class. However, successfully using the initiative process requires broad public support. After all, if the public doesn’t agree with an initiative, it likely will not qualify for the ballot. Even when enough signatures are gathered,[9] it must still win over a majority of voters. To be sure, signature gathering and election campaigns cost a lot of money—the average cost per required signature in 2022 was $16.18 (Ballotpedia n.d.-a)—so money (i.e., material power) is definitely important. At the same time, the corporate class understands that money alone is not enough. They need to convince voters that an initiative deserves their votes.

The now-classic case of this in California is Proposition 22, which was proposed by app-based companies, including Uber, Lyft, Postmates, Instacart, and DoorDash. Prop 22 was a direct response to a 2019 bill passed by the California Assembly (AB 5), which, in general terms, required companies that hired drivers as independent contractors to reclassify them as employees. As employees, drivers would be entitled to a minimum wage, overtime pay, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation insurance, and paid family leave. The app-based companies, not surprisingly, were completely opposed to the new law.

Even more, they initially just refused to abide by the requirements. But, to protect their interests (i.e., to keep themselves from losing a lawsuit), they quickly introduced an initiative, Prop 22, to legally exclude gig workers from the requirements of AB 5. After meeting the signature requirement, they waged an all-out publicity campaign, the most expensive in California history costing more than $200 million (opponents of Prop 22 had less than $20 million to spend). Here’s how one analyst describes what happened next:

To get Prop 22 passed, Uber and Lyft bombarded television, social media, and their own workers with pressure tactics and deceptive advertising, including the flat-out false claim that Prop 22 would increase, not decrease, workers’ rights. As a result, one survey of California voters founds that 40 percent of “yes” voters thought they were supporting gig workers’ ability to earn a living wage. Other voters said they did not realize they were making a choice between guaranteed rights and protections through employment and “an arbitrary set of supplemental benefits . . . designed by the gig companies (Padin 2021).

Ultimately, Prop 22 was approved by large margin, 58.6% to 41.4% in November 2020. Significantly, the final vote represented a major turnaround. In mid-September 2020, only 39% of likely voters approved of the proposition (36% were against it, while 25% were undecided). Thus, the winning margin meant a nearly 20-point gain in less than two months (Luna 2020). Passage of Prop 22 didn’t quite put an immediate end to the issue as it led to spate of court cases that dragged on for years. However, in July 2024, the California Supreme Court reject rejected claims brought by a group of drivers and a labor union that the law was unconstitutional because it interfered with lawmakers’ authority over matters dealing with workers’ compensation (Hussain 2024).

In sum, it is clear that, when their interests are seriously threatened, even in a deep blue state, the corporate class has the capacity to “get what it wants.” In this case, though, it took more than deep pockets: It took a discursive strategy that played an instrumental role in convincing voters that Prop 22 was a progressive cause as opposed to one designed to protect the ability of app-based corporations to maximize profits. On this point, PR firms were employed to create a campaign that prominently featured people of color; Lyft even created a TV ad using a recording of Maya Angelou—the famous poet, author, and leading civil rights activist. In addition, the app-based corporations were able to convince the California NAACP to endorse Prop 22 (Harnett 2020).

There is, I should note, an argument to be made the Prop 22 is progressive and good for drivers. Nonetheless, the fact that app-based corporations were willing to spend more than $200 million on the campaign against AB 5 strongly suggests that they were not fighting for the interests of their drivers or for some larger progressive cause but, instead, were fighting for their own economic interests. The upshot? The “pen” (discourse) may not have been mightier than the “sword” (money), but it was clearly necessary. In other words, the corporate class cannot sole rely on its material and structural power.

Summing Up

A discussion of corporate power and labor policy could easily take up this entire chapter. Since there are other topics to cover, I will conclude this section with a few obvious “lessons.” The first is that the Texas and California have followed different very paths when it comes to labor policy. Second, the key reason for the clear-cut difference in labor policy is the fact that Texas is dominated by Republicans, who willingly and even enthusiastically make common cause with the corporate class, and the fact that California is dominated by the Democratic Party. While pointing this out may seem unnecessary, it is nonetheless important to remember that it makes a difference which party has a dominant governing position. Keep in mind, too, whether this is good or bad isn’t the point; instead, the point is that the corporate class effectively has more power when Republicans control states or the federal government.

The third lesson is a little less obvious: Even in “blue states” such as California, where the wage earning class is relatively united—which requires that racial divisions be at least partly transcended—the corporate class still has great material, organizational, and discursive power that enables it to get what it wants, although, significantly, this is not always the case. Moreover, in California, getting what it wants with regard to labor policy is more of a struggle for the corporate class and often requires a level of compromise that is not seen in “red states” such as Texas.

Climate Change and Energy Policy: Different Paths in California and Texas

According to the Center for American Progress, California has, beginning in 2001 for the next 20 years, “continued to develop, implement, and iterate upon its climate commitments, creating one of the most comprehensive and responsive climate policy landscapes in the world” (Barnes et al. 2021). In 2022, California Governor Gavin Newsom raised the bar further by signing a series of 40 climate bills culminating in the “California Climate Commitment,” which includes a “clear, legally binding” pledge to achieve statewide carbon neutrality,[10] developing a 100% clean energy grid by 2045, establishing a regulatory framework for removing carbon pollution, protecting communities from harmful oil drilling, etc. The Commitment also promised to invest $54 billion in total to fight climate change. This was on top of legislation, discussed earlier, that would lead to a phase out on the sale of new gas-powered vehicles by 2035 (Office of Governor Gavin Newsom 2022) and the state’s “cap-and-trade” program, which began in 2013 (see note for additional discussion of “cap-and-trade”).[11]

California’s stance on climate change has not only remained consistent through both Democratic and Republican administrations—from Gray Davis (D) to Arnold Schwarzenegger (R), to Jerry Brown (D), to Gavin Newsom (D)—but has also significantly exceeded efforts at the federal level. On this point, California’s commitment to fighting climate change was particularly important as the state’s leaders waged an intense legal battle when, during the Trump’s first term, the administration tried to rollback progress on climate change policy, specifically regarding the state’s established rights surrounding emissions standards and clean vehicles (Goodyear 2019). California’s efforts (which had the support of about 20 other states), as the Center for American Progress put it, helped to “hold the line on climate progress during the Trump administration, helping keep the Biden-Harris administration within reach of achieving the emission reductions over the coming decade and beyond deemed necessary by the International Panel on Climate Change” (Barnes et al. 2021). Unfortunately, for California’s political leaders, they have not been as successful under Trump’s second term in office.

To a large extent, Texas has gone in almost the exact opposite direction, although as I noted above, the state is a leader in renewable energy. Surprisingly, perhaps, it was under Republican George W. Bush, when he was governor of Texas (1994-2000), that the state began to encourage the development of renewable energy sources, specifically wind and solar power. According to Kenneth Miller (2020), this was largely because the political leadership of Texas “recognized the economic value of diversifying the state’s energy portfolio, and the business community saw a chance to profit from wind energy if a market for it could be secured.” As Bush himself put it, when speaking to the state’s Public Utility Commissioner, “We like wind …” (cited in Bradley Jr. 2021).

Less surprising, though, is that Bush’s fondness for wind was mostly motivated by the economic interests of two wealthy donors (and members of the corporate class), Sam Wyly and Ken Lay, who hoped to enrich themselves by dominating the industry (Gold 2023). Of course, the turn to renewable energy didn’t mean that the fossil fuel industry was pushed to the side. Far from it. The state’s oil and gas producers have received highly favorable treatment, including industry-friendly regulations, permission to drill anywhere in the state, and protection from any attempts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In 2021, for example, the Texas House went so far as to approve a bill that required state entities to divest from any company that cut ties with or participated in a “boycott” of fossil fuel companies (Douglass 2021).

The effort to protect the fossil fuel industry also frequently overrides the “will of the people.” Texas, if you recall, has a slightly higher percentage of Democrats than Republicans (40% to 39%); in addition, many cities are decidedly “Blue.” Thus, it is not unusual for municipalities in Texas to pursue relatively progressive or liberal policies. To prevent this from happening, the Republican-dominated legislature passed laws such as the Texas Regulatory Consistency Act (mentioned above). The title of act, it is worth noting, reflects, yet again, a discursive strategy; it’s meant to disguise the otherwise clear-cut intent of the Republican-dominated state legislature to prevent Democratic cities in the state from enacting policies that go against the interests of the oil and gas industry and their powerful lobby.

But a city doesn’t have to be dominated by Democrats to feel the wrath of the Republican Party if it dares challenge the oil and gas industry. When a new technique for extracting oil was discovered, known as fracking (see the footnote for a definition),[12] the city of Denton (a suburb near Dallas that slightly leans Republican), voted on a local ordinance to ban fracking; it passed in November 2015 with a vote of nearly 59% in favor. However, as soon as next legislative session opened in 2016, Texas Republicans responded by passing House Bill 40, which pre-empted local bans on oil and gas exploration, thereby negating the Denton anti-fracking vote. The bill was supported by the Texas Oil and Gas Association, the state’s largest petroleum group, which also filed a suit against Denton just hours after the final vote tally was announced (Malewitz 2015).

California’s Energy Lobby: Not Powerless

As with labor policy, however, California’s energy companies are not powerless, although they are far less powerful than their counterparts in Texas who have the full-fledged support of the state government. In California, fossil fuel corporations have structural power, since they are a big part of the state’s economy and, of course, produce a product needed by millions of Californians every single day. In addition, organizations such as Chevron and the Western States Petroleum Association spend millions of dollars on direct lobbying, but they also understand that their activities are subject to great deal of skepticism by the public and legislators.

Thus, they also engage in indirect lobbying by funding fake grassroots or “astroturf” groups to “pump out disinformation about California’s energy policies” (Peterson 2024). According to Laura Peterson, a corporate analyst for the Union of Concern Scientists, one of these astroturf organizations is Californians for Energy Independence (CEI). On paper, the CEI is a nonprofit, bipartisan, advocacy organizations, whose purpose is to educate the public. The reality, though, is quite different as the CEI is generously funded by Chevron to the tune of $5.8 million in 2023, much of which went to pay the salaries of its three employees: A lawyer who works extensively on ballot initiative, the CEO of the California Independent Petroleum Association, and the president of the Western States Petroleum Association. The positions of the CEI advocates for, not surprisingly, align with the positions of its funder and with California’s fossil fuel industry more generally.

Importantly, California’s fossil fuel industry has not been able to derail the state’s push toward progressive climate change policies, nor has it been able to shut down other legislation the industry doesn’t like. However, it has been able to influence the legislative process in other ways. In 2023, for example, Democratic Gov. Newsom attacked oil companies for reaping huge and excessive profits when the average price of gasoline topped $6 a gallon. Newsom called for cap on refiner profits and threatened to impose heavy taxes on any company that exceeded the limit. This sparked a major backlash and became the top priority for oil company lobbyists, who were eventually able to water down the legislation in large part because the Democratic dominated legislature refused to go along with Newsom’s original plan.

The legislation that was finally passed required oil refiners to regularly report information on the factors that contribute to price spikes; it also set up a new watchdog division in the California Energy Commission that would be responsible for collecting and analyzing the data and, ultimately, meting out penalties (Koseff 2023). Two other bills in 2023 were strongly opposed by oil companies, one of which passed (AB 631, which increased penalties for violations of existing oil and gas regulations) and one that was shelved (SB 252, which called for the state’s pension funds to disinvest from the 200 largest fossil fuel companies). (Kimelman 2023)

Another major energy company, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) has been very effective at lobbying for significant rate increases; one of its main target is the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), which has the sole authority to approve rate increases and is arguably the state’s most influential regulatory agency (Walters 2022). Ahead of a CPUC vote in 2023, PG&E “quietly lobbied regulators about plans that may enrich shareholders as customers endure higher rates.” They were able to schedule private meetings with the commission staff to directly plead for their proposed rate increase, an activity that is legal but nonetheless problematic. The requested rate increase was ultimately approved for a combined increase in electric and natural gas rates by $32.62 or 12.8% (however, this was less than originally requested by PG&E).

The CPUC made another controversial decision regarding rooftop solar panels—this decision, it’s important to add, did have an impact on climate change policy. PG&E, Southern California Edison (SCE), and San Diego Gas and Electric (SDG&E) lobbied hard for a sharp reduction in the payments made to solar panel owners. In effect, the changes they wanted would make it far less cost-effective to install rooftop solar. Less solar power, in turn, means a smaller reduction in greenhouse gases. In early 2022, the CPUC issued a proposal that strongly reflected the desires of the utilities’ lobby (Walters 2022), but this resulted in significant backlash by environmental groups, the solar panel industry, and potential consumers. At first the CPUC—which, it is important to emphasize, is composed of members appointed by the governor—backed down.

Ultimately, though, the CPUC gave the large utilities companies what they wanted in December 2022, justifying their decision with the claim that the changes “modernizes” the existing system, “promotes grid reliability, incentivizes solar and battery storage, and controls electricity costs for all Californians” (California Public Utilities Commission 2022). The CPUC also used the utilities’ lobby talking points (i.e., discursive strategy) that the change was needed to promote greater equity, since people in poorer, mostly minority communities, could not afford a rooftop solar panel system and were subsidizing those that could. This was the message pushed by an astroturf organization, the “Affordable Clean Energy for All,” which received a combined $1.67 million from PG&E, SCE, and SDG&E in 2022. But as one critic of the utilities bluntly put it, it is “poppycock” for the utilities to claim to be the ones standing up for equity. “It is very disingenuous and it is a move of power to, on a whim, decide to co-sign for the name of equity and put its name onto something” (quote cited in Marshall-Chalmers and Gearino 2022). Nonetheless, the message seemed to resonate with the public since it was clear that upper- and middle-income households have gotten a disproportionately large share of solar subsidies (Harnett 2020).

A Brief Conclusion

On the issue of climate change policy, California is unequivocally not Texas. The two states are far apart when it comes to addressing the problem. In fact, Republicans in Texas mostly don’t even acknowledge the reality of climate change or, to the extent they do, they have proven to be unwilling to do anything about it. While it is not unreasonable to point to the economic influence of the state’s oil and gas industry as the main reason, California’s experience tells us that money isn’t everything. The amount spent by fossil fuel and other energy companies in the two states on lobbying, both direct and indirect, is comparable. But we can see that lobbyists in California get much less “bang for the buck.”

The most obvious (causal) difference between the two states is, once again, the fact that California is dominated by a progressive/liberal coalition composed of the Democratic Party, labor unions, and a large segment of the population. In Texas, it is largely the opposite. Importantly, though, “words matter” in both states. That is, in a democracy, it is still important to convince the public that the policies the state pursues are reasonable, justifiable, and beneficial to more than just a handful of wealthy corporations and members of the corporate class. Thus,

“Immigration Policy”[13]

It is fair to say that, in over the past 20 years or so, California has become more receptive to undocumented or unauthorized immigrants compared to most other states, including Texas. But this was not always the case—and it’s not necessary to go very far back in history to see this. In 1994, California voters passed Proposition 187, a nakedly anti-immigrant referendum (meaning it was proposed by a member of the Assembly), titled “Save Our State.” It passed by a very wide margin, 59% for and 41% against. The main provisions of Prop 187 barred persons “in violation of immigration law” from using public healthcare services, social services, and public schools, and it required certain state and local agencies to report suspected residents in violation of immigration laws to the state attorney general and to the US Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Not coincidentally, the 1990s was a period during which time the Republican Party was relatively strong in California. Pete Wilson, a staunch Republican, was governor (in office from 1991-1999), was up for reelection that same year and strongly endorsed Prop 187. In fact, Wilson built his campaign around Prop 187, which was exemplified, as Johnson (2020) put it, “in his ominous catchphrase, ‘[t]hey keep coming.” Wilson’s endorsement of the legislation proved to be popular (or, at least, not unpopular), as he defeated his Democratic rival by almost 15 points (55.18% to 40.62%). Equally important, Republicans took control of the State Assembly in 1994 election (41 seats to 39), while they also closed the gap with Democrats in the Senate (17 seats to 21). Ultimately, after several years of legal fighting, most of the provisions in Prop 187 were ruled unconstitutional in a 1998 US district court ruling.

Flash forward 20-plus years, and the political landscape is very different. After going so far as to attempt barring unauthorized immigrants from attending public schools, in 2019, Governor Newsom signed laws allowing unauthorized immigrants to serve on government boards and commissions, and banning arrests for immigration violations inside courthouses throughout the state (Willon 2019). In 2022, moreover, health coverage through California’s Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) was expanded to include 235,000 unauthorized immigrants.* Other significant policy changes include allowing undocumented immigrants to receive driver’s licenses (2013), to have some protections from deportation (2017),[14] and to receive state tax credits (2020). Advocates argue that California now has the “strongest social safety net for undocumented immigrants in the country” (Miranda 2022). *Note. While the 2025-26 California budget did not eliminate health care coverage for undocumented immigrants, it froze new enrollments (beginning on January 1, 2026) and imposed a monthly premium of $30.

In Texas, by contrast, the situation is starkly different. In October 2023, for instance, as two members of the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) asserted, “Texas lawmakers convened for a special legislative session to debate some of the most extreme anti-immigrant bills any state legislature has ever considered.” These measures include one successfully passed law, SB 4, which “threatens humanitarian workers and family members of undocumented immigrants with severe criminal penalties.” Another bill was being debated the same year, although (as of July 2025) has not passed. Nonetheless, according to the two ACLU writers:

If enacted, HB 4 would easily rank among the most radically anti-immigrant bills ever passed by a legislature. The anti-immigrant agenda advancing in the current special legislative session has been fueled by groups with links to white supremacy. Just last month, it was revealed that Texans for Strong Borders — an anti-immigrant advocacy group connected to neo-Nazi Nick Fuentes — urged Gov. Abbott to call a special legislative session to take up anti-immigrant legislation such as HB 4. One of the versions of this legislation being considered would make it a state crime to attempt to enter the State of Texas from Mexico between ports of entry, and authorize state police and sheriffs to arrest, prosecute, and imprison anyone suspected of violating this new and unprecedented state law. Another version would go a step further and purports to authorize these officers — who are not trained in immigration law — to also deport people they suspect of violating this law (Mehta and Blazer 2023).

Politics of Scapegoating: “A Safe Alternative to Class War”

It is not an accident that Prop 187 in California passed during a time of economic recession. The early 1990s was a period of doom-and-gloom in California, as the state suffered significant job losses and its “longest and deepest downturn since World War II” (Groves 1992). It is during these rough economic periods that politicians and ordinary citizens look around for someone to blame. As the most marginalized and powerless group in most societies, unauthorized and sometimes legal immigrants are the easiest target. For politicians, the motivation is clear: Blaming a marginalized group, which is usually primarily composed of ethnic and racial minorities, shifts blame from the politicians to a group that cannot defend itself.

Unauthorized immigrants are, moreover, a viable target because many ordinary citizens (or natives) tend to think of the economy as a zero-sum game, which means if someone “wins” someone else must “lose” (Shih 2016). Since immigrants, and especially undocumented immigrants, tend to work in the lowest paid sectors of the economy, many low-wage native workers believe immigrants are “taking their jobs.” While there is a small grain of truth to this belief, academic research has demonstrated native workers will “shift to jobs that are more complementary in nature and where they have a comparative advantage. And that limited the impact on wages and employment” (Shih 2016).

At the same time, economic downturns are never the fault of unauthorized or legal immigrants. In this regard, scapegoating immigrants becomes a “safe alternative to class war” (Douglas 2016), at least in the context of global capitalism in the 20th and 21st centuries. In an interconnected global economy, the corporate class has the capacity to move across borders to find the most efficient way possible to maximize their profit; sometimes this means moving people across borders, too (i.e., to encourage people to immigrate when certain jobs cannot be easily “outsourced”).

It is the relatively free flow of capital and labor that creates anxiety among ordinary citizens. But instead of blaming the corporate class and the politicians that enable them, blame is place on immigrants; all the easier if the immigrants are ethnic and racial minorities. Typically, immigrants (and especially unauthorized immigrants), to paraphrase Bruce Lee from Enter the Dragon, “Don’t fight back.” This makes them the ideal scapegoat: Native worker can vent their anger, frustrations, and fears on a defenseless group, without fear of retaliation or push-back of any significance.

Prop 187 Push-back and the Ascendance of the Democratic Party in California

In California, though, there was push-back. Strong push-back. Until 1994, the Latino community in California was not a strong or cohesive voting bloc. Prop 187, however, proved to be an extraordinarily powerful and galvanizing force. In an important sense, though, the main effect was fairly mundane. As Gloria Molina (who served as a member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisor from 1991 to 2014), succinctly put it, “We [Latinos] became voters” (emphasis added; cited in Arellano 2019). Importantly, it wasn’t necessarily because the Latino community in California was unanimously opposed to the idea of limiting unauthorized immigration; in fact, at first, Latino voters largely supported the measure (Arellano 2019). Instead, it was the blatantly xenophobic and racist nature of the campaign for the proposition.

Xenophobia and racism were important because they put most Latinos in California in the same boat; regardless of their legal status or citizenship, a large proportion of Latinos in California understood that they were being collectively and unfairly targeted or scapegoated. They also understood that they had collective power, provided they could consolidate into a cohesive voting bloc (the formation of which also required organizational power). Since it was the Republican Party that proposed the initiative and since it was a Republican governor who used Prop 187 to prop up his hitherto flagging chance for reelection—in 1992, Wilson had the worst job-rating of any modern California governor and was behind his Democratic rival by more than 20% (Stall 1994)—Latino voters invariably gravitated toward the Democratic Party. (Kathleen Brown, who was running against Wilson, spoke out strongly against the governor’s support for Prop 187.) To put it simply, “Because of Proposition 187, California is more firmly Democratic today than it has ever been” (Johnson 2020).

Indirectly, then, it was Prop 187 and its aftermath that created the basis for California’s pronounced transition to a “Blue State.” This transition, in turn, has not only led to the state’s development of the “strongest social safety net for undocumented immigrants in the country,” but also, more broadly, to a particularly strong progressive/liberal coalition that has both the will and capacity to challenge the corporate class across a range of issues. On this point, race has clearly played a central role in California politics. Unlike the US as a whole, however, race has become a cohesive as opposed to divisive force. I realize that all this may sound a bit naïve, as if ethnic and racial divisions in California have somehow disappeared. Obviously, that is not the case. Nonetheless, the fact that the majority every ethnic and racial minority in the state (at least as of 2024) identifies as Democratic and that a significant proportion of white adults also identify as Democratic (see box 7.2 above) is what weakens the power of the corporate class.

What about Texas?

As I noted above, Republican legislators in Texas are targeting unauthorized immigrants in an unprecedentedly harsh manner. In 2021, to add to the discussion above, Governor Abbott authorized the use of about 2,500 members of the Texas National Guard to conduct arrests of immigrants crossing the border, even though National Guard members were not law enforcement officers and were not authorized under federal law to enforce federal immigration laws (Human Rights Watch 2021). At the time, the state’s economy was and is doing well.

So, why the scapegoating of immigrants? The simple answer is this: The dominant position of the Republican Party in Texas requires strong support from white voters in particular, and “immigrant bashing” has a proven track record for generating and keeping such support, especially since push-back in Texas has been relatively limited. In 2021, an overwhelming majority (78%) of Republicans approved of Governor Abbott’s handing of immigration and border security, with only 9% disapproving. Even among white Democrats, a majority approved (55%), with only 32% disapproving. Latino or Hispanic adults, overall, did not approve (42%) but this was only slightly higher than those who approved (39%) (all figures cited in Pérez-Moreno 2021). In short, scapegoating unauthorized immigrants is a “winning” political strategy for Republicans (although, in this case, scaremongering might be a better term).

Conclusion: Voting Matters, Race Matters

California and Texas are obviously very different when it comes to labor policy, climate change and energy policy, and immigration policy. Admittedly, too, it’s not news that the core reason for these differences is the dominance of the Democratic Party in California and the Republican Party in Texas. The differences, to repeat a point made at the outset, don’t necessary mean one state is better than or preferable to the other. To some extent, people “vote with their feet” (meaning that an individuals’ preferences are revealed, in large part, by what they choose to do or not do, where they live or leave, etc.). California and Texas have the two largest populations in the country, which means that they both are appealing places (understanding, of course, that it’s not always or even generally possible to freely choose where to live).

This said, it bears repeating that Republican dominance in Texas has helped to maximize corporate class dominance. While overly simplified, it is not unreasonable to argue that the stronger the Republican Party, whether at the state or federal level, the stronger the corporate class. A dominant Democratic Party, on the other hand, doesn’t mean a disempowered corporate class but it generally means a less empowered one. On this last point, it’s important to acknowledge that so-called “establishment” elites within the Democratic Party can and do become quite cozy with and friendly toward corporate class interests, so Democratic dominance does not necessarily inoculate against outsized corporate influence.

A less obvious lesson from this chapter is simple: “Voting matters.” This was an underlying point in the discussion of all three policy issues, as it is ultimately the people of California and Texas who choose their elected state officials, from the state assembly to the governor—although, in Texas, the issue is complicated by the fact that Republicans have been effective at gerrymandering, which has given them disproportionate representation in the state legislature (more on this below). In this regard, voting matters because the core responsibility of elected officials is to promote and pursue specific policy paths.

In California, voting matters even more in the sense that the people are able to directly vote on legislation through the initiative process. Speaking of which, remember that, in California, elected officials were comfortable and even confident using race-based scapegoating tactics to promote Prop 187 because they knew the majority of actual (as opposed to potential) voters approved. However, when the Latino community rose up, using both organizational and collective power, they effectively changed the dynamics of the state’s political system. As a fairly cohesive voting bloc, they were able to maximize their institutional power as well. The result has been not only a 180 degree turn in immigration policy, but also a turn away, although not completely, from unfettered corporate class dominance of the policymaking process in the state.

In Texas, as I noted, the issue is a more complicated because of gerrymandering. Texas, at least demographically, is not deep red. As noted earlier in the chapter, there are slightly more self-identified Democrats than Republicans in the state. Yet, Republicans have a lopsided advantage in the state legislature (Li and Boland 2021), due almost entirely to gerrymandering (that is, drawing electoral districts in a manner that is designed to unfairly favor one party over the other). At the same time, elections for governor or US senate seats where gerrymandering does not come into play (although voter suppression tactics do), Republicans have a strong record of electoral victories. The Texas governorship is not an overly powerful position, but governors have veto power that is difficult to override. Moreover, there “is a governor power to be able to appoint people to boards and agencies all across the state. If you then have a majority of people running a different state agency or running a board that you have appointed, you essentially then have a little bit of power within those agencies as well” (KUT Staff 2017). In short, despite gerrymandering, one can make the argument that Texas has the government that Texas voters want.

Chapter Notes

[1] Figures for California and Texas come from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (2024); the figures for Japan, Germany, France, and Italy from the International Monetary Fund (2024).

[2] For further information on California’s past two-thirds legislative vote requirement, including a useful discussion of additional background and context, see Silva (2008).

[3] The reasons behind Schwarzenegger’s victory are more complicated than I imply here. His victory also reflected a number of other factors, including, of course, who his key opponents were. During the 2003 election, the main rival was Cruz Bustamante, who, according to one set of scholars, lost his one-time lead to “errors and unforeseen events,” some of which tapped into California’s fraught racial relations at the time. For further discussion, see Lazos, Aoki, and Bender (2005).

[4] This figure also includes those who “lean Democrat”; the same applies for references to Republicans.