6 Neuroplasticity

tally

Introduction

My name is Xitlaly (Tally) Chavez Arias, and my passion lies in sports and community nutrition. I am driven by the uniqueness of each individual and intrigued by the details that result in effective task completion. I hold the belief that with a determined mindset, anyone can achieve anything, and that the concept of neuroplasticity provides us a life cheat code to how we can optimize our learning potential.

One of the most significant concepts I gained from my undergraduate motor learning course was the importance of an external focus of attention. Since learning about this, I have been able to apply and analyze this concept in various situations, such as participating in group exercise classes, being a patient in occupational and physical therapy, instructing in our human performance labs, and observing how professors teach for effective learning.

OPTIMAL THEORY OF MOTOR LEARNING

This chapter is adapted from Dr. Gabriele Wulf’s & Dr. Rebecca Lewthwaite’s OPTIMAL Theory of Learning, which focuses on the benefits of external focus of attention in improving movement effectiveness, efficiency, and form (Wulf & Lewthwaite, 2016). The focus is on how the learning process affects our body movements and how automaticity can be achieved through these factors (Wulf et al.,2010). Additionally, I will be sharing my personal experiences as a learner.

It is worth noting that Wulf and Lewthwaite’s, OPTIMAL Theory of Learning covers various aspects such as (a) conditions that improve performance expectancies, (b) factors affecting learners autonomy, and (c) external focus of attention (EFA) on the intended movement effect (Wulf & Lewthwaite, 2016). However, our focus in this chapter will primarily be on the EFA.

Quick History

In today’s world, many people strive to improve their quality of life, accomplish personal goals, and make valuable contributions to society. Often, this involves changing the way we move and carry out physical activities or activities of daily living. Movement is involved in the activation and coordination of muscles and limbs to produce a desired movement pattern, which can be influenced by factors such as attention, learning, and feedback (Enoka, 2008).The concept “rewiring the brain” has become a popular term used to describe the process of behavior and physical change. However, this concept that the brain is capable of change and adaptation has been observed in many scientific studies throughout history.

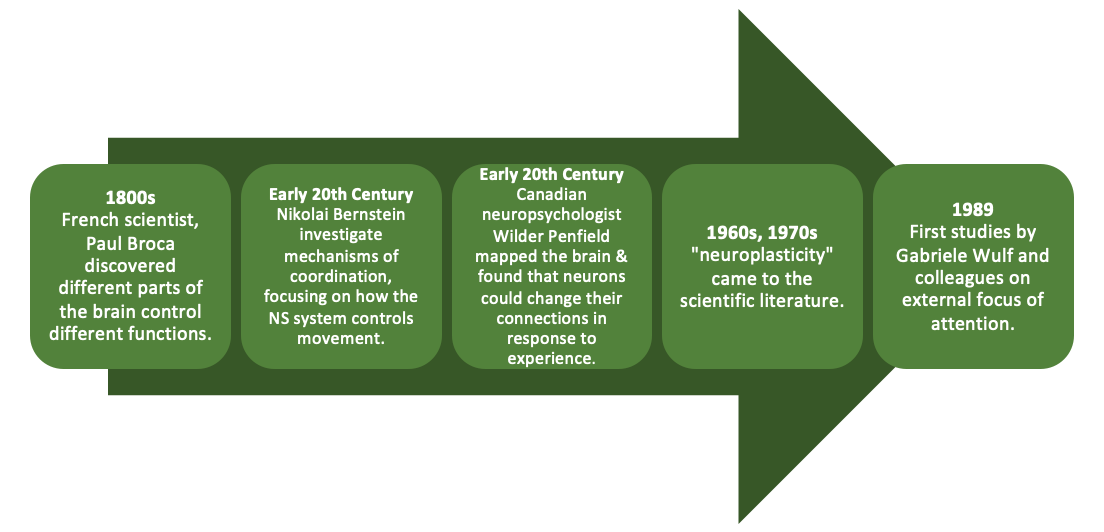

Fig 1. Timeline of the history of neuroplasticity & coordination

In the 1800’s, French scientist, Paul Broca, discovered that different parts of the brain control different functions (Gbur, 2020). In the 1900’s, Canadian neuropsychologist Wilder Penfield mapped the brain and found that neurons could change their connections in response to experience (Kumar & Yeragani, 2011). However, it wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s that the terms “neuroplasticity” began to be used more widely in scientific literature. Researchers such as Michael Merzenich and Mark Rosenzweig conducted groundbreaking studies on the ability of the brain to change in response to experience. They show that the brain’s structure and function could be altered by environmental factors such as learning, injury, and aging (Buonomano & Merzenich, 1998; Rosenzweig, 2003).

Moving forward, research on neuroplasticity has continued to advance with new studies revealing even more about the brain’s remarkable ability to adapt and change. EFA has been shown to enhance neuroplasticity (Gokeler et al., 2019; Wulf & Lewthwaite, 2016). The concept of EFA in motor learning is a relatively recent development in the field of kinesiology and sport science. The earliest research on this topic dates back to the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, when researchers began to explore the role of attentional focus in skill acquisition. One of the first studies on external focus was conducted by Gabriele Wulf and colleagues, who found that golfers who were instructed to focus on the movement of the club (external focus) performed better than those who were instructed to focus on the movement of their own bodies (internal focus) (Wulf et al., 1999). Hang tight, we will dive into this topic more in just a bit!

Coordination on the other hand, is relatively recent in its development. In the early 20th century, Nikolai Bernstein began investigating the underlying mechanisms of coordination, focusing on how the nervous system (NS) controls movement (Biryukova & Sirotkina, 2020). This work laid the foundation for modern research on motor control and coordination, which continues to this day.

Photo by Hal Gatewood on Unsplash

What is Neuroplasticity?

This phenomena of “rewiring the brain” to maximize skills is a reference to the concept of “neuroplasticity”. Similarly as Peter has described in his chapter, neuroplasticity can be broadly defined as the brain’s ability to change and adapt through the formation of neural connections which can lead to the re-learning of patterns of thinking, behavior, or movement (Cramer et al., 2011). The brain’s remarkable capacity to adapt in response to a range of internal and external stimuli allows our brain to modify in response to diverse experiences, behaviors, and environmental factors (Cramer et al., 2011).

Neuroplasticity may occur in response to negative experiences, such as trauma, strokes, or chronic stress (Puderbaugh & Emmady, 2022). The brain may undergo changes that lead to maladaptive behaviors, or pathological consequences but with appropriate interventions, it is possible to “rewire” the brain and promote healing and recovery (Puderbaugh & Emmady, 2022). Neural adaptation is a continual process throughout our lives, not just during childhood or in response to injury. Engaging in activities such as playing a musical instrument, learning a new language, meditating, or discovering a new shortcut home can stimulate the formation of new neural connections and structural changes in the brain, which enable it to accommodate and integrate this new knowledge into our existing cognitive architecture (Benz et al., 2016; Guidotti et al., 2021; Mahncke et al., 2006) Similarly, when we try new movements such as pushing the weighted sled for the first time, substituting a volleyball for a basketball, or mastering a new painting stroke, our brain undergoes rewiring to support these changes. Overall, neuroplasticity is an essential mechanism that enables our brains to adapt to our changing needs and experiences, making it a fundamental component of our everyday lives.

External Focus of Attention

According to the theory proposed by Wulf and Lewthwaite (2016), directing one’s attention externally results from a movement rather than internally towards the movement itself can lead to greater efficiency, effectiveness, and automaticity in task performance.

What is attention?

Attention can be referred to paying attention to what’s happening around you (e.g., environment monitoring), the physical cues related to a task (e.g., scope of physical cues ), the ability to concentrate even with distractions, and focusing on important cues for movement (Wulf & Lewthwaite, 2016).

EFA leads to enhanced neuroplasticity and ultimately, more effective learning by optimizing the activation and connectivity of different brain regions involved in motor learning and control (Wulf et al., 2001). It has been shown to enhance the functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and motor areas of the brain, which in turn improves motor skill acquisition and retention. The OPTIMAL theory has been applied in various fields such as sports, rehabilitation, and physical therapy to improve motor learning and control. Studies have consistently shown that an external focus on the intended movement effect enhances performance and learning compared to an internal focus on body movements (Wulf et al., 2001; Wulf & Lewthwaite, 2016). Additionally, movement kinematics start resembling those seen at a later stage of learning when learners adopt an external focus rather than internal.

Understanding the stages of motor learning is important for motor control and EFA because it helps to identify the learner’s current stages of learning and the appropriate instruction to promote learning. In the initial stage of learning, the focus of attention is typically internal, where learners need to understand the movement mechanics and develop proper movement patterns. However, as learners progress to the later stages of learning, EFA becomes more appropriate, as learners shift their attention away from internal mechanics to the effects of their movements. External focus promotes the development of automatics, more efficient movement patterns and can enhance performance. Therefore, understanding the stages of motor learning and appropriate use of EFA can improve learning and performance outcomes.

How does the mountain goat approach jumping over the chasm?

Wulf and Lewthwaite (2016) use the analogy of a mountain goat preparing to jump over a chasm to explain EFA. When you imagine a mountain goat trying to get to the other side of the chasm, do you think its attention is fixated on the details of the jump? Instead of focusing on the technicalities of jumping, such as muscle contractions or leg extension, the mountain goat’s attention is directed towards the external goal of reaching the other side of the chasm. The idea is that this movement skill is a natural and intrinsic focus for movement skill, and it indicates the goat’s apparent “knowledge” of how to jump. Animals do not engage in constant internal communication about the most effective way to move its limbs when they are in survival mode. Over time, due to varying teaching, coaching styles, and approaches to movement, humans tend to shift away from the natural and intrinsic focus of movement skill. From my personal experience, I remember an instructor using complex language such as “hip flexion with knee extension while pointing your toes”. As someone with a background in kinesiology, I found myself momentarily stumped and confused while trying to decipher this exercise due to the heavy use of scientific terminology. Clearly, she’s intelligent and understands human movement, but I questioned whether the instructor was aware that not everyone understood these terms, and made the movement feel more unnatural. Additionally, the instructor heavily emphasized using internal focus of attention for a simple leg lift exercise, which was not necessary. Wulf and Lewthwaite (2016) found that focusing on the goal of movement rather than the specific movements themselves can result in coordination pattern showing an advancement in skill and efficient motor unit recruitment, minimal co-contraction of agonist and antagonist muscles., increased force output, increased functional variability, and greater movement accuracy.

Photo by Robin GAILLOT-DREVON on Unsplash

promoting automaticity

Why is external focus crucial for optimal motor performance?

The answer lies in its ability to serve two purpose:

- directing attention to the task goal

- reducing self-focus

As a result an external focus contributes significantly to goal action coupling

By consistently producing successful outcomes and making movements feel effortless, an external focus leads to enhanced expectancies for positive outcomes. When instructions are given that encourage a person to focus internally on their body, it can cause them to overthink and become overly aware of their movements (McKay et al., 2015; Wulf & Lewthwaite, 2010; Perreault & French, 2015). This can lead to poor performance and disrupt automaticity by inefficient use of their muscles and disrupt automaticity of the movement. The internal focus can also lead to conscious control over their movements, which can hinder their overall performance. On the other hand, when individuals adopt an EFA on the desired outcome, they are able to direct their attention away from themselves and perform better with improved learning outcomes. In other words, focusing on the outcome of the movement rather than the movement itself can lead to better results.

Movement of effectiveness

Balance

Several research studies have used balance-related tasks to evaluate the differences in performance and learning outcome associated with an external versus internal focus. When it comes to improving balance, directing one’s attention externally toward minimizing movements on a platform or markers, it is more effective than focusing internally on one’s own body movements (Laufer et al., 2007; Wulf et al., 2009). External focus is also more effective in responding to perturbation, or sudden and unexpected disruptions to the body’s stability or equilibrium (e.g, being pushed or pulled off-balance, or experiencing a sudden change in surface or terrain).

When reading about EFA in balance, it unlocks a childhood memory. During P.E. in grade school, when my teacher would ask us to perform a simple quad stretch, my classmates and I would often lose our balance and burst into laughter. Someone in the group would suggest looking at the floor (external focus) or foot to maintain balance (internal focus), which I now realize is an example of using EFA. I have witnessed this phenomenon on numerous occasions, which is not limited to my childhood memories during P.E. class. It has persisted through my recent yoga class (tree pose), stretching routines during physical therapy, and even stretching with family and friends after a workout. Wulf and Lewthwaite (2016) discovered that performance outcomes are worse with either no focus instructions or with internal focus instruction compared to external focus instructions.

Accuracy

Outcome measures like hitting a target accurately are used to evaluate the impact of attentional focus on movement effectiveness. Directing the attention towards the object or the intended trajectory may enhance accuracy compared to focusing on your own hands, arms, or wrist. This can be applied to improving accuracy in throwing balls, darts, and frisbees. Accuracy in generating a precise amount of force is significantly higher when their attention was on the device compared to focusing on the foot.

As previously discussed, we humans tend to overthink and try to consciously control our movements (we can thank our multifaceted, enlarged frontal lobe for that). Next time you’re playing disc golf, try shifting your focus to the external outcome of the disc landing in the target or basket (external focus), rather than getting caught up in technical thought like wrist flick or forearm position when practicing your tomahawk throw.

Photo by Ted Johnsson on Unsplash

Movement efficiency

One way to measure movement efficiency or economy in movement is through direct measures such as electromyographic (EMG) activity, oxygen consumption, and heart rate. Indirect measures such as maximum force production, move speed, or endurance have been used in other studies. By achieving the same movement outcome with less energy expenditure, improved efficiency can be demonstrated.

Muscular activity

External focus on a target during tasks like shooting a basketball or throwing darts has been shown to result in reduced EMG activity in the antagonist muscles and improve accuracy. Movement efficiency as a result of attentional focus is shown by the reduction of EMG activity not only in the targeted muscle groups. In addition, directing attention on weight being lifted rather than body parts being used results in lower EMG activity and more efficient movement. When analyzing the power spectral density of the EMG signal, the internal focus can cause unnecessary recruitment of larger motor units within the muscle, resulting in reduced movement efficiency. This highlights the negative impact of internal focus on motor control.

This concept is not only applicable to sports, but also to occupational therapy. Instructing a client to pick up a cup with an external focus on the goal of drinking water, rather than the internal focus on the mechanics of hand-to-mouth movement, can promote movement efficiency by reducing unnecessary muscle recruitment.

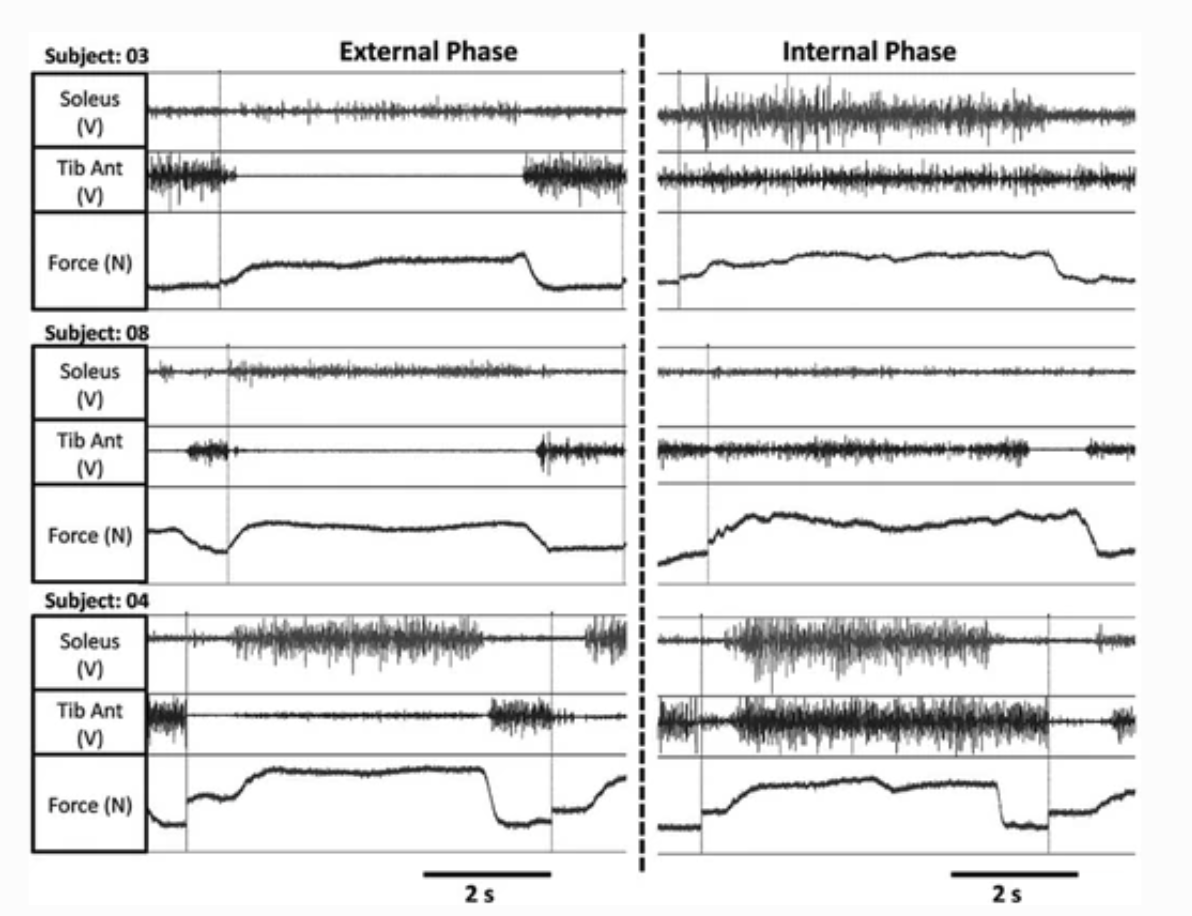

Fig 2. Lohse et al. (2011) analyzed EMG and force data from three participants performing a task that involved pushing against a force platform with their foot at 30% of maximal force. The study found that external focus on the platform, as opposed to internal focus on the muscle responsible for force production (soleus), resulted in different outcomes. Participants who used external focus had reduced activity in the agonist and antagonist muscles and produced force more accurately. Note. From “Neuromuscular effects of shifting the focus of attention in a simple force production task,” by Lohse, Sherwood, and Healy, 2011, Journal of Motor Behavior, 43, p. 178

Maximum force production

Optimal coordination is needed to produce maximum forces. Tasks such as isokinetic contractions, maximum vertical jump height, standing long jump, and discus throwing have shown greater maximum force production is achieved when participants adopt an external focus, compared to internal focus or control condition (Marchant, 2011). The results are associated with a greater maximal force production and reduced muscular activity.

When you’re training your next client in their pursuit of reaching their one-rep max (1RM), instead of asking your client to concentrate on the contraction of their chest muscle while training, try instructing them to push the barbell or weight away towards the sky. This EFA will help them complete the lift successfully by recruiting the necessary muscle and producing greater force.

Speed and endurance

Enhanced movement speed and endurance benefits in overall movement efficiency using EFA.

Incorporating EFA in training:

EFA in speed and endurance:

- Running a race: Instead of telling the runner to focus on their breathing or movement of their legs, instructing them to focus on the finish line or a landmark in the distance.

- Cycling: instructing the cyclist to focus on the road ahead or a specific destination rather than their pedaling technique or breathing pattern.

- Swimming: Encouraging the swimmer to focus on pushing water back, rather than pulling their hands back (Freudenheim et al,. 2010; Stoate & Wulf, 2011)

- High-intensity interval training: instructing participants to focus on completing the entire set or round of exercise, rather than each individual movement or muscle group.

Overall, movement is the ultimate outcome of motor learning and control. EFA has been found to improve movement performance by optimizing movement kinematics, reducing energy expenditure, and enhancing movement accuracy. Studies have shown that EFA improves movement kinematics by reducing joint variability and increasing joint range of motion. Moreover, EFA may reduce energy expenditure by minimizing unnecessary muscle activity and enhancing movement economy. Practicing EFA can lead to faster running times (Porter et al., 2010), decreased oxygen consumption (Shucker et al., 2009; Shucker et al., 2013), improve swimming performance, increased muscular endurance by performing more reps (Marchant et al., 2011), and reduce heart rate and EMG activity. Finally EFA has been shown to enhance movement accuracy by optimizing spatial and temporal aspects of movement execution.

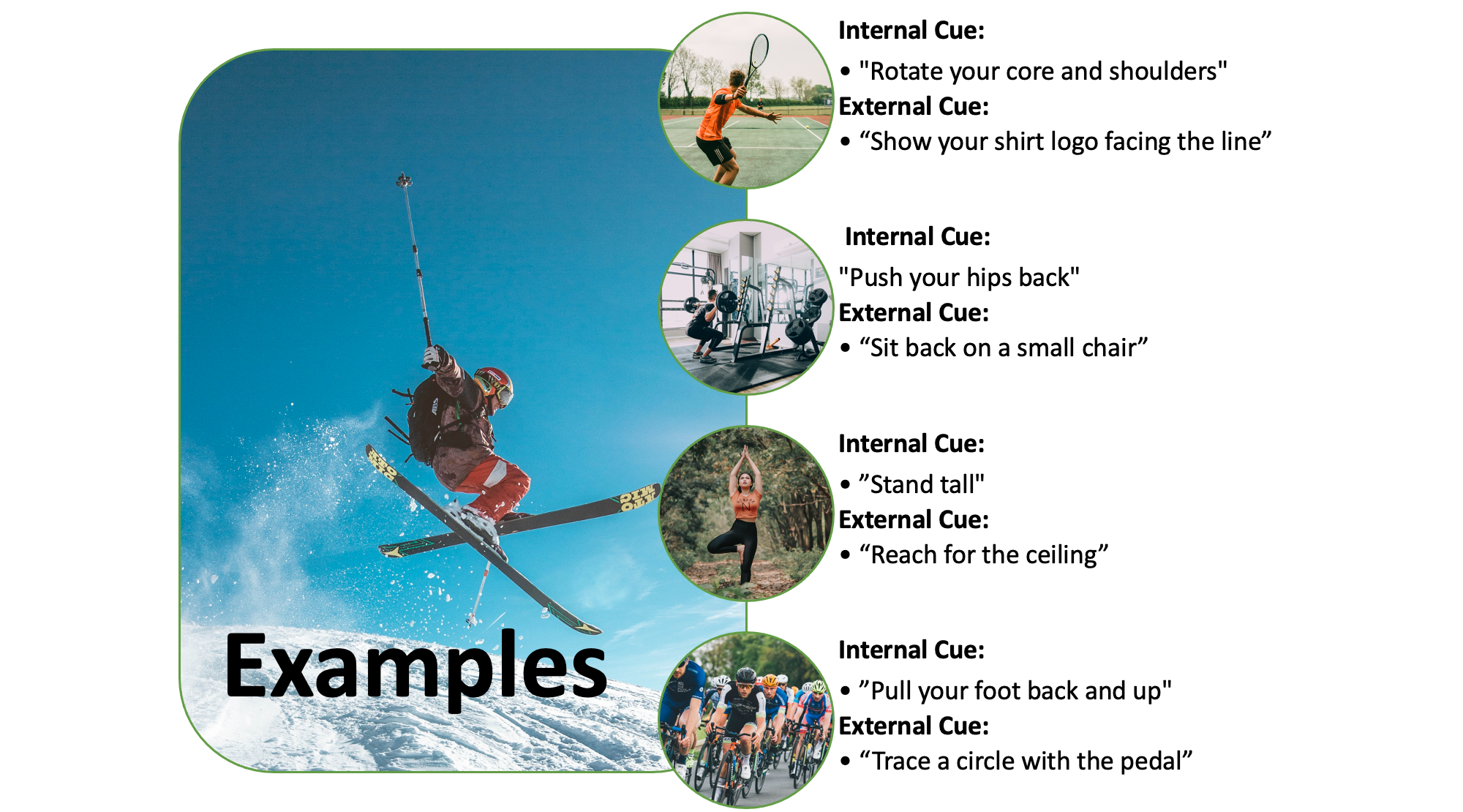

Fig 3. Internal cues vs. external cues

Movement Form

EFA not only improves coordination within and between muscles but also facilitates coordination at a broader level. Movement form can be maximized with external rather than internal focus on movement kinematics. For example this can be telling a golfer “swing the clubhead through the ball” rather than “keep your elbow straight”. This will help the golfers focus on the desired outcome and allows their body to naturally optimize movement kinematics. For rowers, this could be focusing on pushing the oar away towards the water rather than pulling the oar with the arms. This approach can be used in achieving optimal outcome and minimize the possibility of injury or strain caused by improper movement form, you could suggest to your client to visualize the exercise as sitting on a chair or bench, rather than emphasizing pushing their hips back. The attentional focus of the performer is therefore crucial in movement coordination, and an external focus on the intended movement effect has been shown to enhance all aspects of performance, regardless of skill level, task, age, or disability.

Activity: Stepping to Success: A One-Legged Challenge for Improved Motor Performance!

Welcome to the One-Leg Stepping Challenge! This motor task is designed to test your ability to alternate flexing and extending your leg at a comfortable pace for 60 seconds while seated. In this challenge, you’ll be using both legs, and we’ll be testing the effects of different focus conditions on your motor performance. The task is highly controlled, safe to perform, and is an excellent way to investigate the effects of attentional focus on both non-paretic and paretic leg performance. So, get ready to challenge yourself and have some fun!

- Perform the single-leg-stepping task for 60 seconds while seated.

- Alternate flexing and extending your leg at a self-selected comfortable pace.

- Perform the task twice, once with the external focus condition and once with the internal focus condition. For the external focus condition, a line will be taped to the floor such that when you place your foot on the line your knee is flexed at an angle of 90 degrees. For the internal focus condition, the line will be removed.

- Measure your movement speed for each condition by calculating the average absolute angular velocity in the anterior-posterior plane.

- Compare your results for the two conditions and see if there is a difference in your performance.

Why is this important?

EFA is important because it has been shown to enhance movement performance and efficiency in a variety of tasks. When individuals focus externally, they direct their attention towards the intended movement outcome or the environment, rather than the specific movements or body parts involved. This allows the motor system to rely on automatic processes and optimize neuromechanical coordination, resulting in improved movement patterns. From the neuromechanical perspective, external focus has been found to facilitate optimal muscle activation patterns, reduce unnecessary muscle activity, and improve intramuscular coordination. It has also been associated with changes in neural activity and increased activation of cortical areas associated with motor learning and control. These changes in neural activity and motor control can lead to improved movement efficiency, speed, and accuracy. Overall, EFA is important because it allows individuals to tap into automatic processes and optimize neuromechanical coordination, resulting in improved movement performance and efficiency.

Please provide your feedback here

References:

Benz, S., Sellaro, R., Hommel, B., & Colzato, L. S. (2016). Music makes the world go round: The impact of musical training on non-musical cognitive functions—A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 2023. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02023

Biryukova, E., & Sirotkina, I. (2020). Forward to Bernstein: Movement Complexity as a New Frontier. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00553

Buonomano, D. V., & Merzenich, M. M. (1998). Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annual review of neuroscience, 21(1), 149-186. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.149

Cramer, S. C., Sur, M., Dobkin, B. H., O’Brien, C., Sanger, T. D., Trojanowski, J. Q., … & Vinogradov, S. (2011). Harnessing neuroplasticity for clinical applications. Brain, 134(6), 1591-1609. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr039

Enoka, R. M. (2008). Neuromechanics of human movement. Human kinetics.

Freudenheim, A. M., Wulf, G., Madureira, F., Pasetto, S. C., & Corrěa, U. C. (2010). An external focus of attention results in greater swimming speed. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 5(4), 533-542. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.5.4.533

Gbur, G. (2020, February 6). Scientific Revelation through a Disproven Theory. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/2020/02/06/scientific-revelation-through-a-disproven-theory/

Gokeler, A., Neuhaus, D., Benjaminse, A., Grooms, D. R., & Baumeister, J. (2019). Principles of motor learning to support neuroplasticity after ACL injury: implications for optimizing performance and reducing risk of second ACL injury. Sports Medicine, 49, 853-865 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01058-0

Guidotti, R., Del Gratta, C., Perrucci, M. G., Romani, G. L., & Raffone, A. (2021). Neuroplasticity within and between functional brain networks in mental training based on long-term meditation. Brain Sciences, 11(8), 1086. https://www.mdpi.com/1234256

Kumar, R., & Yeragani, V. K. (2011). Penfield – A great explorer of psyche-soma-neuroscience. Indian journal of psychiatry, 53(3), 276–278. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.86826

Laufer, Y., Rotem-Lehrer, N., Ronen, Z., Khayutin, G., & Rozenberg, I. (2007). Effect of attention focus on acquisition and retention of postural control following ankle sprain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 88(1), 105-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.028

Lohse, K. R., Sherwood, D. E., & Healy, A. F. (2011). Neuromuscular effects of shifting the focus of attention in a simple force production task. Journal of Motor Behavior, 43(2), 173-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222895.2011.555436

Mahncke, H. W., Connor, B. B., Appelman, J., Ahsanuddin, O. N., Hardy, J. L., Wood, R. A., … & Merzenich, M. M. (2006). Memory enhancement in healthy older adults using a brain plasticity-based training program: a randomized, controlled study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(33), 12523-12528. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0605194103

Marchant, D. C. (2011). Attentional focusing instructions and force production. Frontiers in psychology, 1, 210. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00210

Marchant, D. C., Clough, P. J., & Crawshaw, M. (2007). The effects of attentional focusing strategies on novice dart throwing performance and their task experiences. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(3), 291-303. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2007.9671837

McKay, B., Wulf, G., Lewthwaite, R., & Nordin, A. (2015). The self: Your own worst enemy? A test of the self-invoking trigger hypothesis. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 68(9), 1910-1919. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2014.997765

Perreault, M. E., & French, K. E. (2015). External-focus feedback benefits free-throw learning in children. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 86(4), 422-427. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2015.1051613

Porter, J. M., Nolan, R. P., Ostrowski, E. J., & Wulf, G. (2010). Directing attention externally enhances agility performance: A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the efficacy of using verbal instructions to focus attention. Frontiers in psychology, 1, 216. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00216

Puderbaugh, M., & Emmady, P. D. (2022). Neuroplasticity. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557811/

Schücker, L., Anheier, W., Hagemann, N., Strauss, B., & Völker, K. (2013). On the optimal focus of attention for efficient running at high intensity. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2(3), 207. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031959

Schücker, L., Hagemann, N., Strauss, B., & Völker, K. (2009). The effect of attentional focus on running economy. Journal of sports sciences, 27(12), 1241-1248. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410903150467

Sirotkina, I. E., & Biryukova, E. V. (2015). Futurism in physiology: Nikolai Bernstein, anticipation, and kinaesthetic imagination. Anticipation: Learning from the past: The Russian/Soviet contributions to the science of anticipation, 269-285.

Stoate, I., & Wulf, G. (2011). Does the attentional focus adopted by swimmers affect their performance?. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 6(1), 99-108. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.1.99

Rosenzweig, M. R. (2003). Effects of differential experience on the brain and behavior. Developmental neuropsychology, 24(2-3), 523-540. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2003.9651909

Wulf, G., Landers, M., Lewthwaite, R., & Toöllner, T. (2009). External focus instructions reduce postural instability in individuals with Parkinson disease. Physical therapy, 89(2), 162-168. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20080045

Wulf, G., Lauterbach, B., & Toole, T. (1999). The learning advantages of an external focus of attention in golf. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 70(2), 120-126.

Wulf, G., & Lewthwaite, R. (2010). Effortless motor learning? An external focus of attention enhances movement effectiveness and efficiency. Effortless attention: A new perspective in the cognitive science of attention and action, 75-101.

Wulf, G., & Lewthwaite, R. (2016). Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 23, 1382-1414. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0999-9

Wulf, G., Shea, C., & Lewthwaite, R. (2010). Motor skill learning and performance: a review of influential factors. Medical education, 44(1), 75-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03421.x

Wulf, G., Shea, C., & Park, J. H. (2001). Attention and motor performance: Preferences for and advantages of an external focus. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 72(4), 335-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2001.10608970

acronym: optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning

using an outside force or applying your attention to out outside of body

refers to the execution of a physical action or behavior

synaptic connections in response to learning, where the nerve wire together when learning a task

cognitive processes that allow individuals to selectively focus on relevant information while ignoring irrelevant information in the environment

the motion of objects without considering the forces causing the motion and the motion of various systems, such as the movement of a car or the flight path of a ball.

smoothness of movement without conscious control

refers to how well a movement achieves its intended goal or outcome.

refers to the ability to perform a task or movement with the least amount of energy expenditure and minimal wasted effort.

EMG stands for electromyography, which is a technique used to measure and record the electrical activity of skeletal muscles. It involves placing small electrodes on the skin overlying the muscles being studied, which then detect and amplify the electrical signals produced by the muscle fibers during contraction.

refers to the specific way in which an individual performs movement or exercise. This includes posture, joint angles, muscle activation, and range of motion.