7 Introduction to Human Gait

Emmett McMahon, MS

Chapter Introduction

Gait simply put is an individual’s “manner of walking”, and gait analysis looks to examine specific periods within gait. This chapter will look to give a newcomer’s overview of gait analysis and associated methods of gait analysis. As someone with great interest in gait analysis and practical applications, this chapter will also serve as a look into a student’s journey into understanding the complexities of gait. As a graduate student beginning their journey into understanding gait analysis, I hope to expose others to how valuable understanding the gait cycle can be for anyone in research or healthcare.

Brief Overview of Anatomy

Because this is an Introduction to Human Gait and Analysis, prior knowledge of anatomy is not assumed. Below will be interactive resources and strategies to develop foundational knowledge of anatomy. To better understand the gait cycle as a whole it then becomes very pertinent to have familiarity with basic anatomy. Phases within the gait cycle each will require all muscles of the lower limbs to varying degrees. Where using sEMG can be beneficial in understanding muscle activation during different phases of gait. (Agostini et al., 2020)

Terminology common in Gait Analysis

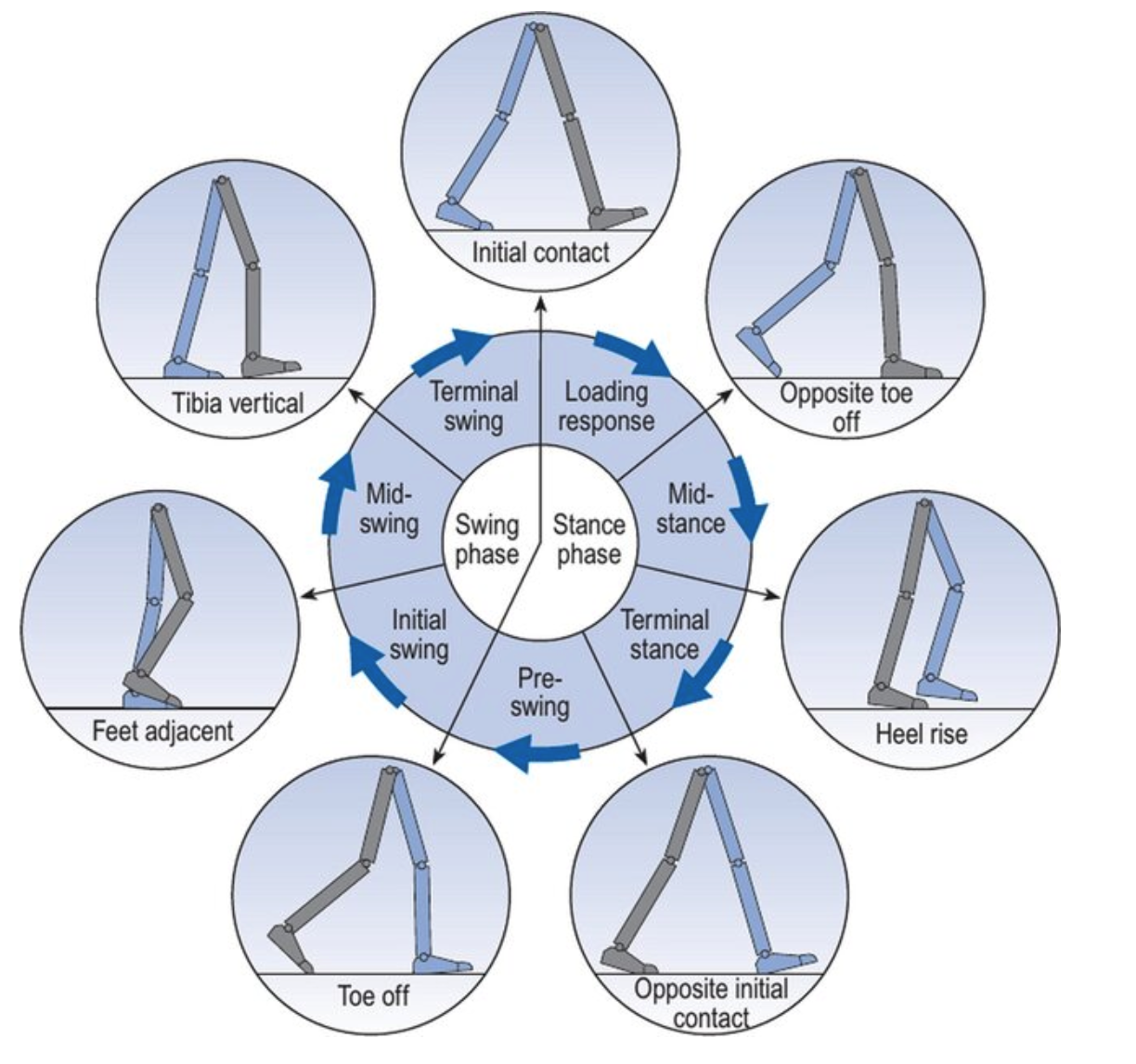

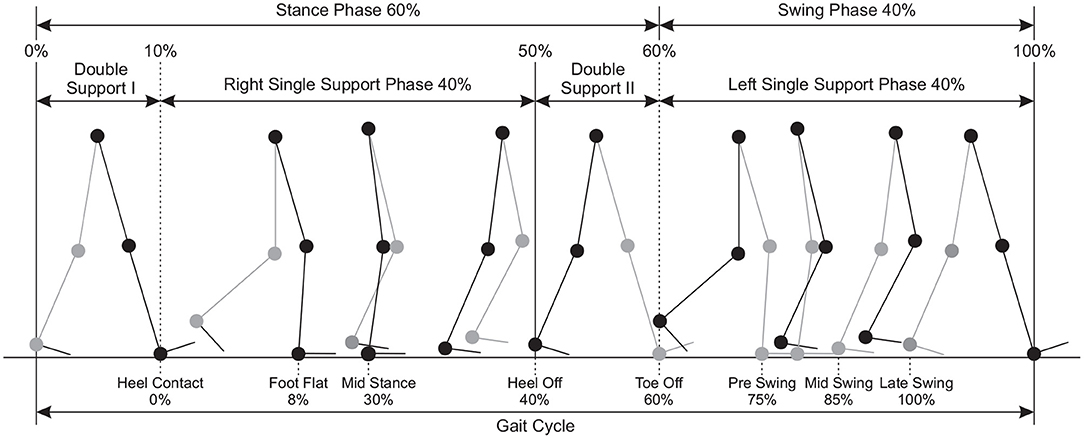

It can be overwhelming and admittedly a little monotonous, when learning new vocabulary. I will now lay out the “events” you will encounter in instrumented or observational gait analysis. Each term will have a matching picture that you will be asked to navigate to. An easy way to develop a firm grasp of the meaning of each term is to demonstrate it yourself. (Whittle, 2008) In the gait cycle each “cycle” is then defined from to initial contact to the ipsilateral initial contact. In human walking gait 60% of the cycle will be spent within stance and 40% spent in swing, the majority of the time with contact with the ground. A key difference between walking gait and running is the percentage of stance and swing. (Whittle, 2008)

Major Events throughout the gait cycle: (Whittle, 2008)

- Initial contact

- Opposite toe off

- Heel Rise

- Opposite Initial Contact

- Toe off

- Feed Adjacent

- Tibia vertical

- (Initial contact)

Stance phase which lasts from initial contact to toe off can be further broken down into four events. (Whittle, 2008)

- Loading response

- Midstance

- Terminal stance

- Pre-swing

Swing phase then can as well be separated into three events. (Whittle, 2008)

- Initial swing

- Mid-swing

- Terminal swing

It important to know that while these are some of the more common descriptors used in the field there are variations from source to source. Rancho Los Amigos regarded can be looked as well for apt descriptions of gait, which will be listed below. I believe as someone just beginning to learn the basics of human gait, it is important to be familiar with terms in the literature.

What are the three functional tasks of gait ?

- Weight Acceptance

- Single Leg Support

- Swing Leg Advancement

As mentioned earlier stance phase begins with initial contact (IC), leading into loading response, followed by mid-stance, and the terminal stance at the end. Weight acceptance will begin immediately following IC and loading response, where weight begins to be transferred onto an outstretched limb while the contralateral limb experiences unloading. (Observational Gait Analysis, 2001) As this happens the body will absorb the force transferred onto the outstretched limb and facilitate movement in a forward path.

Single limb support is defined by the weight being transferred to a single stable limb while the opposite begins swing phase. Mid-stance begins as weight is transferred from the heel and ‘moves’ forward to the tarsals. (Observational Gait Analysis, 2001) In this same instance weight progresses to a midpoint before terminal stance and where weight is now in front of the support leg. Single limb support then ends at terminal stance.

Swing limb advancement is defined by the initial support limb being unloaded and foot beginning pre-swing to come off the ground during initial swing. The limb is moved from behind the body gradually to be brought out in front where mid-swing occurs and terminal swing as the limb becomes outstretched.

Energy consumption and the gait cycle

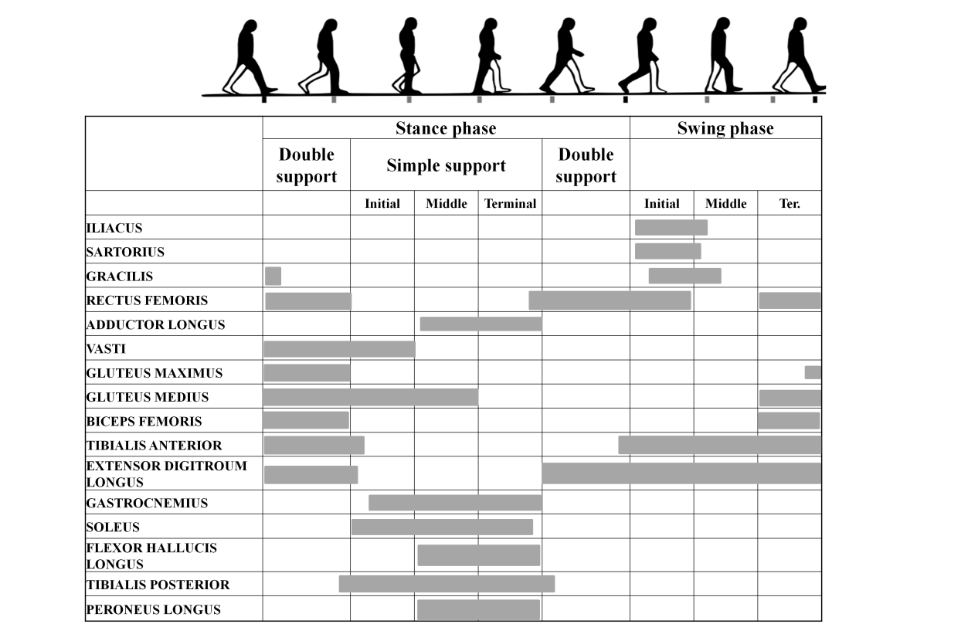

During the human walking gait cycle there are three areas where energy will be consumed. The first area that energy will be consumed is when the body controls the deceleration when the swing phase is ending. Second, the impact at heel strike (initial contact) along with subsequent propulsion during the swing phase. The third area where energy will be consumed is the center of mass is transported horizontally and vertically throughout the gait cycle. (Malanga, n.d.) Each of these three areas where energy consumed in then related to when certain muscles are activated. It might then be assumed when certain muscles remain activated during periods of the cycle where they should not, an individual’s gait pattern might become inefficient. Below is a reference table from (Bonnefoy-Mazure, Armand. 2015) that clearly shows when specific muscles are activated during the gait cycle.

Muscle activation in gait

It will be helpful to have the above visual aid when discussing the muscle activation patterns in the human gait cycle. The above visual aid from (Bonnefoy-Mazure, Armand. 2015) uses different nomenclature than has been discussed in this chapter thus far. Simple support refers to single support, during the phases of the gait cycle.

Gait in Younger individuals

As humans begin to learn the proper and most efficient methods of walking there can be observed differences between a younger individual and older individuals. Many researchers have looked at the nature of gait in young children and work done by (Sutherland et al. 1988) examined the primary differences.

- Base of support is wider

- Both the stride length and speed are slower resulting in a shorter cycle time

- There is no observed heel strike in young children

- Stance phase results in little knee flexion

- Swing limb is externally rotated entire duration of swing phase

- There is only small amounts arm swing present during cycle

It was observed as well by (Sutherland et al. 1988) young children as well activate many of the muscles responsible in gait longer throughout the cycle than adults.

Gait in older individuals

One of the biggest differences between young children’s gait patterns and that of older adults (above the age of 6o years) is general slowing of the cycle. (Murray et al., 1970) Gait patterns of the elderly populations may be influenced by either a pathological condition and the general effects of aging itself. The exclusion of older individuals with pathological gait issues, reveal that the gait pattern seen in older adults is slower in comparison. It was carefully noted by (Murray et al. 1969) that older individuals gait patterns do not resemble any pathologic patterns.

Changes in the gait pattern due to age, generally will be observed in the ten year span from 60-70 years of age. There is a decrease in stride length, increase in cycle time with slowed cadence, and widening of the base of support. (Whittle, 2008) In addition an increase percentage spent in stance phase, however this and many other changes are not as pronounced as the changes of base of support, gait cycle duration, and length of the stride.

There have been proposed rationale as to the purpose of gait pattern changes on the individual. It was proposed by (Murray et al. 1969) that a purpose of the slowing of gait in older individuals is to increase relative levels of safety. By decreasing stride length and increasing the base of support, balance in turn becomes much easier to maintain for an individual. The increase in overall cycle time then leads to a reduction in duration that one must spend in single leg stance. With an increase in stance phase in double support security is additionally added. (Murray et al. 1969)

Key Takeaways

- As we age a variety of changes and disruptions in the “normal” gait pattern may be observed

- Disruptions into the normal gait pattern will likely be due to not just one single source

Abnormal Gait Patterns

As stated previously in other chapters in Introduction to Neuromechanics, there are certain responsibilities of the locomotor system in order to properly facilitate walking. If for any reason there is a disruption in the locomotor system it can present major challenges in the gait cycle. Outlined by (Whittle, 2008) there are four tasks that must be accomplished in order to consider proper function.

- Each limb must be able to support under body weight in periods of single leg stance

- Balance maintained either through static movements or dynamic when in single leg stance

- A limb in swing must be prepared to accept body weight at terminal swing

- Adequate power able to be maintained to create necessary movements required for walking

In pathological gait patterns these motor functions are accomplished by abnormal movement and increase the energetic cost of walking. Walking aids can also help an individual to walk in a more typical gait pattern. If any of the above four tasks are unable to be completed an individual will no longer be able to walk. (Whittle, 2008) Because gait is extremely complex it takes a great deal of skill and expertise to identify the root cause of an gait abnormality. An abnormal gait pattern may be due to any aspect of the neuromuscular or structural elements of the locomotor system.

Because the human gait cycle is the result of complex neurological and structural processes the sources of gait abnormalities have the potential to manifest themselves in similar appearances. This makes it important to separate descriptions of gait abnormalities and the specific cause of the abnormal gait pattern. (Whittle, 2008)

It is important to remember when looking at pathological gait patterns is that there are two main reasons that an abnormal type of movement may be performed.

- The individual does not have a say in how their body is being moved and is ‘forced’ by an underlying issue.

- The movement being observed is due to trying to compensate for a problem that will need to be identified.

Below are three commonly observed abnormalities in human gait patterns. These three are shown because being some of the more common seen visually in abnormal patterns of gait.

Lateral Trunk Bending:

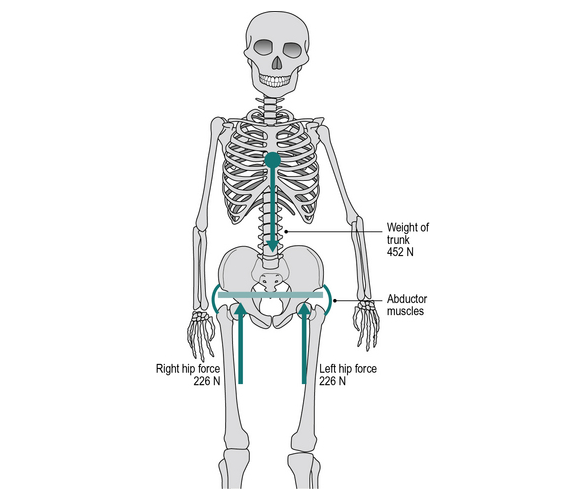

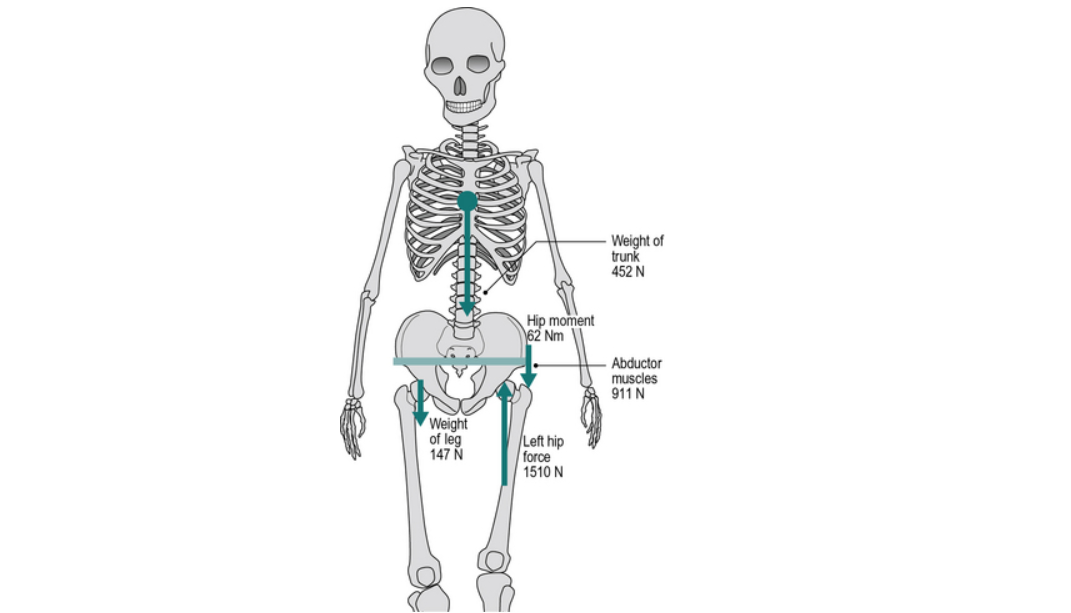

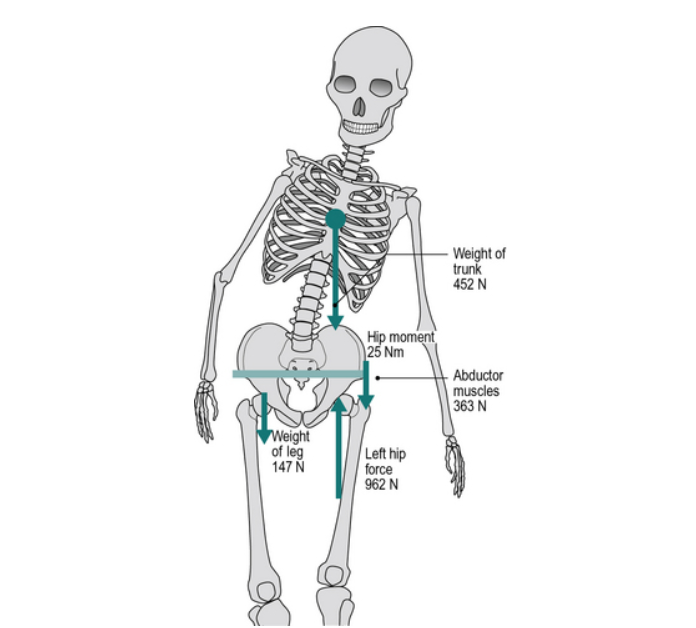

At the trunk “bending” is a]observed due to a desire to reduce overall force that acts in the abductor muscles and in the hip joint when the body is in single leg stance. This type of trunk bending is best seen in the frontal plane. When the body is in double support the force is distributed evenly and the leaning will not be observed. Below are some diagrams that will show the force placed on different segments of the body.(Whittle, 2008)

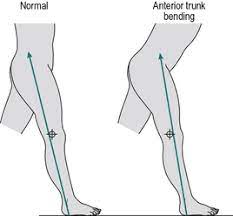

Anterior Trunk Bending:

This type of abnormality is characterized by the early tendency to bend the trunk in the stance phase. This will be seen in the sagittal plane of movement. Anterior Trunk bending is a attempt to make up for weak knee extensors. The ground reaction force that is normally seen behind the knee will instead be seen directly in front of the knee. Opposition of the external torque placed and attempts to flex the knee which is opposed by the quadricep muscles. If there is a discrepancies in strength of the quadricep muscles, a buckling movement may be observed. (Whittle, 2008)

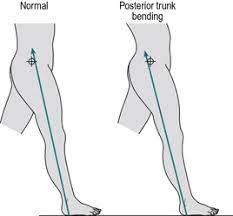

Posterior Trunk Bending:

Typically seen when there is an issue the strength of the hip extensors the body has a hard time matching the torque demand place on the hip. The trunk will the be pulled “backwards” because the ground reaction force is now instead going behind the hip axis rather than in front, contributing to the posterior bend. (Whittle, 2008)

The below resource is helpful in looking more at gait abnormalities in human walking.

M. W. Whittle, Gait analysis: an introduction. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2014

Key Takeaways

- Abnormal gait patterns are complex and multifaceted and by using combinations of instrumented and observational gait analysis a clear picture can be developed

- As mentioned earlier it is important to refrain from only paying attention to one abnormal issue you may be observing

Closing thoughts

The human walking gait pattern is a complex process that can be broken down into various specific phases and even further broken down into sub phases. This chapter aims to give someone interested in human gait the initial knowledge base to begin the journey into gait analysis. There are additional resources that I recommend that you checkout if any of the topics covered over the chapter seemed interesting to you. Below is an activity designed to start thinking how exactly gait patterns can differ between individuals and practice describing what it is that you might notice.

Observational Gait Activity

- Gather 2-3 people and designate one person as the scribe

- The idea of this activity is to get you to be a critical observer in how someone moves

- Each person will complete three walks for 5 meters down a marked walkway

- The first trial you will walk normally and the scribe will record what the other viewer notices

- The second trial you will close your eyes

- The third trial you will have your eyes open but moving your head side to side

- After each trial has been completed take note the changes that occur in each trial

- The final output of the complex motor task we all do each and every day is walking

- Even a small disruption to in our body can manifest itself in different visual changes in someone’s gait pattern

Please provide your feedback here

References

Agostini, V., Ghislieri, M., Rosati, S., Balestra, G., & Knaflitz, M. (2020). Surface Electromyography Applied to Gait Analysis: How to Improve Its Impact in Clinics? Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 994. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00994

M. F. Bear, B. W. Connors, M. Paradiso, M. F. Bear, B. W. Connors, and M. A.

Neuroscience, “Exploring the brain,” Neurosci. Williams Wilkins, 1996.

Bourne M, Sinkler MA, Murphy PB. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Tibia. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526053/

Farley, C. T., and D. P. Ferris. “Biomechanics of Walking and Running: Center of Mass Movements to Muscle Action.” Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 26 (1998): 253–85.

C. Freudenrich, G. J. Tortora, and B. H. Derrickson, Visualizing Anatomy and Physiology. Wiley, 2013.

Gupton M, Munjal A, Kang M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Fibula. [Updated 2022 May 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470591/

Observational Gait Analysis. Downey, CA: Los Amigos Research and Education Institute, Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, 2001.

R. N. P. D. Elaine Nicpon Marieb, P. B. Wilhelm, and J. B. Mallatt, Human Anatomy, Media Update, Books a la Carte Edition. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company, 2011.

M. W. Whittle, Gait analysis: an introduction. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2014

W. H. Organization and I. S. C. Society, International Perspectives on Spinal Cord

Injury. World Health Organization, 2013.

defined by the weight being transferred to a single stable limb while the opposite begins swing phase

defined by the initial support limb being unloaded and foot beginning pre-swing to come off the ground during initial swing