The Psychological Connection

5.4 Implementing Community Interventions

Photo by Wokandapix is licensed under the Pixabay LicenceWhat do we mean by implementation? As mentioned above, having a good community intervention depends on how well the program has been designed and tested out to be effective. It is also important to keep in mind how ready or interested the setting or people are in the intervention because if the community does not really want the program, it is very unlikely to be accepted or used by the community members.

Case Study 5.4

A Classroom Exercise and Lessons in Implementation

One high school teacher performed an interesting exercise with his students in a class. First, he inserted cotton in a transparent bottle. Next, he lit a cigarette and placed it so the smoke entered the bottle. After a while, the students could see that the cotton had blackened and retained a part of the tar and other harmful elements of tobacco. In a simple way, this showed the effect of smoking on the lungs. When adolescents are informed about the negative health consequences of smoking, they may be less likely to use tobacco. However, the achievement of good preventive results with this group of adolescents does not only depend on having clear intervention ideas, such as the demonstration of the cotton in the bottle but also enlists the help of the students and teachers in changing the social pressures to smoke. It also involves the larger community including the media, such as in Case Study 5.3. Furthermore, it is important to have the groups actively invested in the program, and this can occur when they participate in the design and implementation of the intervention. In part, the success of the intervention also depends on when and where this activity will occur during and after school; these type of factors influence how well the program is implemented.

In Case Study 5.4, we are focusing on community dynamics—a critical factor that is often forgotten when interventions are developed. By considering the community dynamics when implementing an intervention, this helps shape whether the intervention should be more traditional, with an expert delivering a packaged prevention program, or more in line with the spirit of Community Psychology, where community partnerships actively bring those voices into the design of the intervention.

Theory is an important aspect when community psychologists develop and implement ecological community interventions, but there is more that is needed to make long-lasting changes. Other critical areas involve the skill levels and knowledge of those who implement the programs, the interest and readiness for the intervention among the community members, and the availability of the needed resources required by the intervention. We can illustrate these points with the example of smoking, which was reviewed in Chapter 1. If you can believe it, there was a time when commercials had physicians endorsing tobacco use (Stevens & Dropkin, 2019)! In the 1940s and 1950s, few people thought that tobacco use was harmful. It was not until tobacco use and its effects were studied for years that public perception, and then policy, were changed. Over the past 50 years, there have been significant reductions in smoking in the US (Biglan & Taylor, 2000). This reduction was due to evidence gathered over time on the consequences of tobacco abuse, which helped change people’s opinions about smoking.

Communities may vary in the degree of awareness of a specific social problem, as few were willing to address tobacco use as a problem before the 1960s. With the Surgeon General’s report, the public began to view tobacco as a harmful social problem. This shows that, in practice, some communities may be more or less prepared for changes. That is why the degree of “community readiness” often determines whether our community interventions will be effective. From this perspective, implementation is a key process: since it is not enough to design effective programs, it is also necessary to attend to the factors that make the desired social change possible.

Case Study 5.5

The Importance of Public Awareness in Prevention Efforts

Investigators have tried to prevent intimate partner violence in different Latin American countries. In one of the countries, there was frequent debate on television about gender-based violence, and this led to several organizations advocating for greater protection of women. In another country, there was little publicity or awareness of these types of issues, and there was not the same type of organizational advocacy. In other words, the issue was not publicly discussed nor were there organizations promoting community awareness of this topic.

In the above case study, the level of community readiness was high in the first country but low in the second, which led to more intimate violence prevention programs being launched in one country than the other.

Let’s go back to the above cases 5.3 and 5.4 showing tobacco prevention to again illustrate the importance of community readiness and successful implementation. The “Communities That Care” program well represents this concern for awareness of community contexts and the implementation process (Oesterle et al., 2015). This is a Community Psychology program that aims to reduce drug dependency, criminal behavior, violence, and other harmful behaviors among adolescents. The program is often initiated through a local community coalition, in which different organizations collaborate to develop united action for preventive purposes. This means that adolescents receive a consistent message from different agents of the community and are exposed to social norms that promote healthy habits. In addition, these community agents participate in choosing the evidence-based practices that will be implemented. Accordingly, they are jointly responsible for both the actions that are carried out and the introduction of adjustments to adapt them to the specific characteristics of the community. Finally, it is important that preventive actions have the intensity, continuity, and dose necessary to have the most significant impact in the community context. Dose refers to the number of sessions or the duration of a program and influences the level of results we can achieve. For example, we cannot expect one social skills training session to have the same result as a semester-long program. Just like a muscle, the more these programs are exercised, the stronger they are. Thus, beyond the quality of the programs, how the community supports the idea and helps to carry it out affects how the program is applied on multiple levels in the community. The application of the Communities That Care program in neighborhoods has been found to reduce the overall consumption of alcohol, cigarette, and smokeless tobacco, as well as delinquent behavior. This video link provides more information about the Communities That Care model and its effectiveness.

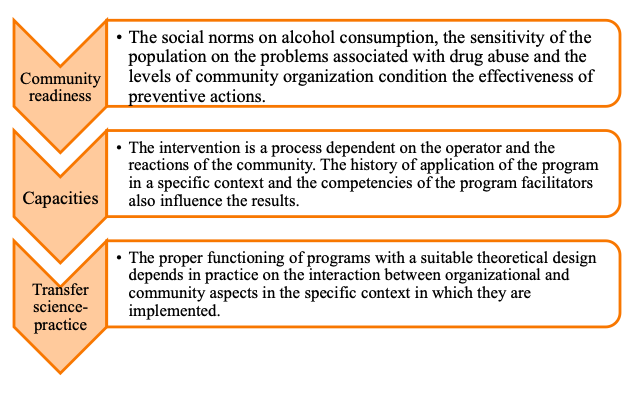

In Figure 3, we have summarized some of the key factors in the implementation process when trying to prevent alcohol abuse.

Sequence of actions that goes from the planned on paper to actions in natural community contexts. Good implementation depends on the skills of the community psychologists involved and the degree of community readiness.

Degree to which the community is prepared for the behavioral and social changes that are intended by the intervention.

Refers to how much of the intervention they do deliver: for example, number of sessions, number of hours, time of application of the program, and so on.